Abstract

Objectives

Hong Kong has among the highest mobile phone usage rates in Asia. Although the mobile phone may foster adolescents’ communication with parents and peers, there is also concern that some teens may become dependent on the mobile phone. The present study investigated the psychometric properties of the Mobile Phone Dependence Questionnaire (MPDQ) in a sample of young adolescents.

Method

The MPDQ was translated and validated in a Hong Kong sample of adolescents (N = 733) from S1 (ages 11–12), S2 (ages 12–13), and S5 (ages 16–17) in six schools representing various levels of socioeconomic status. A subset of 27 students participated in focus groups on the topic of adolescents’ mobile phone usage.

Result

Confirmatory factor analysis identified three psychological factors represented in adolescents’ responses to the MPDQ: compulsive text messaging, making and receiving a high number of calls, and obsessive thinking about using the mobile phone. Using the criterion of a score 2 standard deviations above the mean, 3.41% of students would be classified as showing mobile phone dependency, with a higher rate among females than males.

Discussion

Positive examples of mobile phone usage were mobile parenting to monitor children, and children's use of the phone to seek mobile tutoring from teachers. E‐counselling and e‐tutoring are suggested as ways to provide support to adolescents using technology that is already an integral part of their lives.

What is already known about the topic

The Mobile Phone Dependence Questionnaire has been used to measure mobile phone dependency.

The term ‘mobile phone dependency’ has been used to describe a pattern of usage in which ‘addiction’ was referred to as excessive use of mobile phone that can be deemed problematic.

Some researchers reported that parents used the mobile phone for the ‘mobile parenting’ of their teenagers.

What this topic adds

Three psychological factors of mobile phone dependency, namely, ‘compulsive texting messages’, ‘compulsive making and receiving calls’, and ‘obsessive thinking of using mobile phone’ was confirmed by confirmatory factor analysis.

When the more stringent criterion of exceeding the mean +2 standard deviations was used, 3.41% of the sample would be classified in the category of mobile phone addiction.

One interesting finding was that students in Hong Kong like to use the mobile phone to ask for tutoring from the teacher, termed mobile tutoring.

Mobile phones have become virtual extensions of their youthful owners, according to a recent study by a market research firm (The Standard, Citation2010). The study involved more than 12,000 Asian youths aged from 8 to 24 who were quizzed on their lifestyles, habits, and use of technology. Hong Kong topped the mobile phone category, followed closely by Singapore and South Korea, all affluent markets in which families can afford a second or third mobile phone (The Standard, Citation2010). In Hong Kong, 85% of youth in the 8‐ to 24‐year‐old age group had mobile phones; in the 12‐ to 14‐year‐olds, the rate was 93%, almost double the regional average for that age group. The view of the effect of mobile phone dependency is consistent with previous studies (Chen & Katz, Citation2009; Katz & Askhus, Citation2002; Ling, Citation2004; Srivastava, Citation2005) showing that mobile phone usage directly or indirectly affects many aspects of human relationships and human interactions by providing a direct and private communication channel.

The term ‘mobile phone dependency’ has been used to describe a pattern of usage in which ‘addiction’ was referred to as excessive use of mobile phone that can be deemed problematic. Although this term has been applied mostly to adults, the high usage rates among adolescents suggest that it may also be a concern in younger populations.

The Mobile Phone Dependence Questionnaire (MPDQ; Toda, Monden, Kubo, & Morimoto, Citation2004) has been used in several studies to measure mobile phone dependency and its relation to health‐related lifestyle (Toda, Monden, Kubo, & Morimoto, Citation2006) among university students in Japan. Although the MPDQ shows promise as a research instrument, the psychometrics of this measure has not been established. In addition, the measure has been used to examine dependency and gender differences in usage solely in adult samples, although the usage rate is also extremely high among adolescents in Asia, and very little is known about gender differences in this younger age group. The current study is designed to address these gaps in the literature.

The relationship between mobile phone and everyday life among youths

The mobile phone is an important communication technology in the everyday life of young people. In the United Kingdom, 19‐ to 24‐year‐old youth agreed that their mobile phone was more important than their television (The Carphone Warehouse, Citation2006). When young UK mobile phone users lost their mobile phones, they reported that they felt frustrated, angry, and isolated (Fox, Citation2006).

On the other hand, the mobile phone also provides a free choice for its user to isolate himself or herself, to disconnect from certain persons or locations (Fox, Citation2006). The same technology allows teens to ignore calls from their parents (Green, Citation2001; Ling, Citation2004).

Scholars argued that using the mobile phone might set up barriers between people and their physical situations. Engagement with the mobile phone disconnected people from physical connections and co‐present activities, activities occurring around them (De Gournay, Citation2002). Persson (Citation2001) commented that mobile phone usage signals a type of inaccessibility and erects a communicative barrier between the caller and others who are physically near. Gergen (Citation2002) argued that people became unavailable for people co‐present when they were using the mobile phone. He advocated a concept of ‘absent presence’, which is the situation in which people were psychologically present in a place but also rendered absent at the same time. The intentional barriers set up by the mobile phone will affect communication and relations with parents and friends.

Mobile phone communication and relations with friends

Research on Grade 8 students in Toyko showed that sociable students seemed to use mobile phone mail effectively to widen their interpersonal relations (Kamibeppu & Sugiura, Citation2005). Many students positively stated ‘Using a mobile phone enables wider inter‐personal relations,’ ‘Using mobile a phone enables deeper inter‐personal relations,’ and ‘Using a mobile phone enables better relationship‐building with friends.’ On the other hand, about half of the students felt insecure about using the mobile phone. About 30% had had their mobile phone messages ‘misunderstood’ and a common worry was that ‘he/she must be ignoring my message.’ The researchers viewed these concerns as indicators of a risk for dependency.

Mobile phone communication and relations with parents—mobile parenting

Some researchers (Kopomaa, Citation2000; Ling, Citation2004; Oksman & Rautiainen, Citation2002; Rakow & Navarro, Citation1993) reported that parents used the mobile phone for the ‘mobile parenting’ of their teenagers. The mobile phone allows parents to communicate directly with their children (Srivastava, Citation2005), and children can call their parents for help, such as being picked up after activities (Ling, Citation2004; Ling & Yttri, Citation2006). Other researchers (e.g., Castells, Fernandez‐Ardevol, Qiu, & Sey, Citation2007) have reported that better parent–children relationships were fostered by the mobile phone. One of the reasons why people preferred to use the mobile phone to communicate with their family members was because with voice contacts they had more capacity to articulate personal emotions (Sawhney & Gomez, Citation2000).

However, teens’ behaviour often limits the benefits of the mobile phone in family life. Green (Citation2001) and Ling (Citation2004) noted that although youths understood the importance of their mobile phones with regard to safety and emergency situations, they avoided parents’ monitoring by not answering their mobile phones, claiming that they did not hear it ring or that the battery was dead. Teens’ mobile phone usage can also serve to exclude parents. Matsuda (Citation2005) noted that Japanese parents found it difficult to monitor their teens. Many youth use the mobile phone at dinner tables in Japan (Matsuda, Citation2005) and in the USA (Cellular News, Citation2006). Ito (Citation2005), in Japan, and Green, in the UK (2001) have reported that the mobile phone was also used in private bedrooms to avoid parents’ monitoring.

The MPDQ as a measure of dependence

Research using the MPDQ has found that female university students’ high scores for mobile phone dependence are associated with poorer health practices (Toda et al., Citation2006) and poorer mother–child relationships (Toda et al., Citation2008). However, currently, the measure has been used only for case identification; subjects with scores exceeding 1 standard deviation (SD) above the mean were put in the high‐dependence category (Toda et al., Citation2006). The measure has not shown the factors structure mobile phone dependency. The measure has also shown gender differences in adults’ mobile phone usage. Several studies suggest the possibility of gender differences in adolescents’ mobile phone usage as well. Kamibeppu and Sugiura (Citation2005) found that more girls than boys ages 13–18 in Japan felt strongly that they ‘cannot do without keitai (mobile phone).’ The results of another study (Toda et al., Citation2008) suggested a possible gender gap in how the phone is used, with more female youth than male youth tending to express their feelings by using pictographs.

Purpose of the present study

Given the gaps in the current literature, the present study investigated the psychometric properties of the MPDQ in a sample of young adolescents. First, 200 participants were randomly selected from the original 733 participants for exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with oblique rotation (Costello & Osborne, Citation2005) to explore the underlying factor structure that best fit the dataset. CFA was then used to confirm the factor structure derived from the EFA procedure. CFA was then conducted with the boy and girl groups separately to test for multiple group invariance of mobile phone dependency. Focus group interviews were also used to gather qualitative information about teens’ mobile phone usage in everyday life, as there is no qualitative description in previous studies (Kamibeppu & Sugiura, Citation2005).

A discriminate function analysis (DFA) would then be employed to measure the predictive strength of the mobile phone dependency from latent variables from CFA and other independent variables such as genders, grades, birthplace, and senior versus junior students.

Method

Participants

Participants were 733 students from S1—Grade 8 (137 boys and 68 girls), S2 Grade 9 (149 boys and 80 girls), and S5 Grade 12 (192 boys and 107 girls) who attended six secondary schools in Hong Kong. The schools represented a range of socioeconomic backgrounds; three were subsidised by the government, two were Christian private schools; and one was associated with a labour organisation.

Measures

Focus group interviews

27 students, 12 girls and 15 boys, randomly selected from S1, S2, and S5 (9 students from each form) were selected for 30‐minute focus group interviews on the usage of mobile phone and its effects. There were 3 focus group interviews with 9 students each. The groups were each led by two female graduate students in education. Question like ‘Who do you usually talk to on the phone?’ All focus group interviews were audiotaped and transcribed for analysis. Students were told not to repeat what they learned from others in the group.

MPDQ (Toda et al., 2004)

All students completed the MPDQ, which includes 20 items on mobile phone dependency (e.g., ‘I give my mobile phone more priority than clothes and food,’ ‘I send mail even when I am at work or in class,’ ‘I send lots of long email messages,’ and so forth), 22 items on the usage of mobile phone (e.g., ‘Average weekly number of outgoing/incoming calls for social purpose or academic purpose,’ ‘Average time(s) using the following Apps’), and the effects on communication with friends and family members (e.g., ‘Average weekly number of incoming calls that were perceived as: wanted or unwanted,’ ‘What is/are the reason(s) that make you NOT receive/reply to calls, besides surveys and sales promotions?’). Only the 20 items relating to mobile phone dependency were used in the current study. Each item response was scored on a Likert scale (0, 1, 2, 3). Item scores were then summed to provide an overall mobile phone dependency score ranging from 0 to 60. Higher scores indicated greater dependency. Subjects exceeding the mean +1 SD are put in the high‐dependency category (Toda et al., Citation2006). In the current study, a more conservative criterion of +2 SD was also used. Students completed the questionnaire in about 20 min.

Procedure

This research was approved by the Higher Education Research Committee (HERC) that provided ethical approval. Both parents and students were fully informed and gave consent to the study. It was explained clearly that they have the right to quit the study at any time. The questionnaires were assigned code numbers so that the students’ answers could be treated confidentially. The same process was used for the focus groups. Students completed the MPDQ during their assigned library period. Focus groups were held at three schools, at the end of the school day.

Data analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was adopted to examine the psychological constructs represented by participants’ responses to the MPDQ. Multi‐sampling modelling was conducted to test the gender gap in mobile phone dependency. The analysis was carried out in three steps. First, the internal structure of the assessment type item‐sets was explored using factor analysis with oblique rotation (Costello & Osborne, Citation2005). Items with a loading below 0.30 were dropped from the EFA. The second step was to test the measurement models using maximum likelihood CFA to validate the factor structure of the measurement model. Solutions that had reasonable fit characteristics (e.g., comparative fit index (CFI) or Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) > 0.90, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.08) were used in subsequent analyses. Third, multi‐group analysis was used to test the structural equivalence of the instrument when administered to two groups (i.e., boys and girls), to determine whether the instrument measures the same concepts in the two groups. Byrne (Citation2006) states that if the fit of the unconstrained model is good and the fit of the constrained model is similarly good, or just a little worse, then this is indicative of measurement invariance. The fit is measured using a variety of indices: the TLI, the CFI, and the RMSEA. In regard to the comparison of the fit of the unconstrained and constrained model, Little (Citation1997) proposes that the CFIs should differ not more than 0.05 to speak about multiple groups measurement invariance.

Multi‐sample modelling to investigate the difference of non‐dependency and dependency groups was not possible to conduct due to the small size of dependency group. Independent sample t‐tests was used to examine the difference between the dependency group and non‐dependency group in the factor structure of mobile phone dependency. A chi‐square test was used to investigate the difference between the dependency group and non‐dependency group on the usage of mobile phone and communicating with friends and family members.

Results

Psychological factors of MPDQ

Step 1: EFA model of mobile phone dependency

The results of the EFA indicated that three factors were extracted from 20 items with 61.73% of total variance explained. The Kaiser‐Meyer‐Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO) test value was 0.831, greater than 0.70, indicating sufficient items for each factor.

Step 2: CFA models of mobile phone dependency

Mean responses, SDs among items of the questionnaire are presented in Table . Goodness of fit for the three‐factor model of the MPDQ (Toda et al., Citation2006) was evaluated using maximum likelihood estimation procedures in AMOS.

Table 1. Mean and standard deviation of the items in the MPDQ

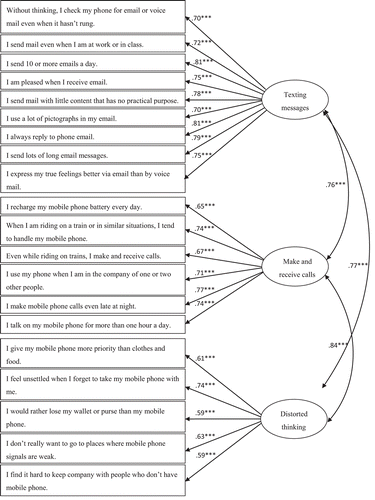

The model of the MPDQ statistically fitted the results of the samples. The model indices were shown to conceptually fit and to be acceptable, with CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.93, and RMSEA < 0.08 of models (Fig. 1). Therefore, the three psychological factors of mobile phone dependency, namely, ‘texting messages’, ‘making and receiving calls’, and ‘distorted thinking’ were confirmed.

Step 3: Multi‐samples modelling

The difference between the model based on the girls’ data and the model based on the boys’ data was 0.930 − 0.922 = 0.007, less than 0.05. This value indicates multiple group invariance (see Table ).

Table 2. Model fit summary of unconstrained and constrained models, boy and girl groups

In the pairwise comparison, there was no significant difference of the measurement weights between the boy and girl groups, 17.167/17 = 1.01, p > .05. Therefore, there were no parameter differences between the boy and girl groups. The correlation among the three psychological factors were relatively high, rtexting messages × making and receiving calls = 0.76, p < .001, rmaking and receiving calls × distorted thinking = 0.77, p < .001, and rdistorted thinking × texting messages = 0.84, p < .001.

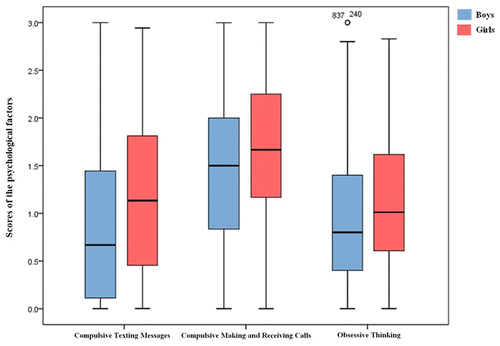

The mean for each of the three psychological factors ranged between 0 and 3, with 3 indicating that all of the psychological constructs contributing to the factor were selected, and 0 indicating that none had been selected (Brown, Budzek, & Tamborski, Citation2009). The means for compulsive texting messages using the mobile phone were Mboy = 0.85 (SD = 0.78) and Mgirl = 1.14 (SD = 0.79), the means for compulsive making and receiving calls using the mobile phone were Mboy = 1.46 (SD = 0.82) and Mgirl = 1.69 (SD = 0.78), while the means for obsessive thinking of using mobile phone were Mboy = 0.90 (SD = 0.71) and Mgirl = 1.13 (SD = 0.69). As reflected in the box plot (Fig. 2), the means and medians of the girl group's scores on the three psychological factors were higher than those of the boy group.

Both boys and girls viewed ‘compulsive texting messages’ as the least important factor in mobile phone dependency with the factor loading being 0.73 and 0.63, respectively. They also thought ‘compulsive making and receiving calls’ and ‘obsessive thinking of using mobile phone’ shared similar importance for mobile phone dependency. However, girls weighted these two factors as more important than the boys did.

A followed up discriminate analysis was conducted, which revealed one discriminant function. It explained 100% of the variances, canonical correlation R2 = 0.54. The discriminant function significantly differentiated the dependency of the mobile phone, Wilks's lambda = 0.464, chi‐square (8), significance > 0.001. There were eight variables used in the analysis, with the results showing that compulsive text messaging loaded the highest (r = 0.87), obsessive thinking was the second (r = 0.75), and making and receiving calls was the third (r = 0.66). Types of phone (r = −0.15), gender (r = 0.12), and place of birth (r = −0.08) loaded less than the three variances from CFA. Grades (F = 3.615, significance = 0.058) and form (F = 0.148, significance = 0.701) of the students are insignificant to discriminate the dependency. In addition, 90.7% of originally grouped cases were correctly classified. The variables compulsive texting, obsessive thoughts, and making and receiving phone calls, those identified from CFA, were predictor variables of mobile phone dependency.

Impact of mobile phone dependency

Independent sample t‐tests indicated that the dependency group had significantly higher scores than the non‐dependency group for all three factors of the MPDQ: compulsive texting messages, making and receiving calls, and obsessive thinking of using mobile phone. Compared with the non‐dependency group, the dependency group also had significantly higher scores for using smartphones, making and receiving calls daily and weekly, perceived wanted and unwanted calls, and calling and being called by lovers. In the focus group interview, more junior high school students than senior high students used their mobile phone to make calls and to send messages to home and friends through SMS and Facebook. However, more senior high school students used their mobile phone to make whatsApp and to call their parents. All junior high students in the focus group liked to use mobile phones to talk to their class teachers related to homework and/or assignments (see statement 1). An interesting finding was that junior high school students liked to call parents to have frequent contact with their family, to fulfil their family roles, to share experiences, and to receive emotional and physical support from their parents (see statement 2), while senior high school students wanted to build their social network, develop their independence from parents, and control their own affairs via the mobile phone.

Statement 1: ‘Teacher, I couldn't follow your procedures that you taught me in class to solve the maths homework, I have tried out other methods you taught but still couldn't solve the problem. Could you please give me some cues or hints to solve the problem?’ (S1 boy student, 13)

Statement 2: ‘Mom, I want to stay in school until 6:00 every Thursday to join an activity held by the geography club, I am interested in the topic of global warming, I like to understand and improve the environmental pollution in Hong Kong, please allow me to join.’ (S2 boy student, 14)

Discussion

Psychological factors of mobile phone dependency

Three psychological factors of mobile phone dependency, namely, ‘compulsive texting messages’, ‘compulsive making and receiving calls’, and ‘obsessive thinking of using mobile phone’ was confirmed by CFA. The first two factors referred to repetitive and compulsive behaviour, sometimes with no practical purpose. These factors included items such as ‘I send mail even when I am at work or in class’ and ‘I make mobile phone calls even late at night.’ Such behaviour is similar to what has been called ‘technological addiction’, which is thought to involve excessive human–machine interactions that develop when people rely on the device to provide psychological benefits, such as an expected reduction in negative mood states or an expected increase in positive outcomes (Griffiths, Citation1999; Shaffer, Citation1996). Excessive usage of the mobile phone to obtain pleasurable outcomes is thought to lead to addiction (Charlton, Citation2002; Orford, Citation2001). The third factor could be referred to as obsessive and recurrent thinking about using the mobile phone, thoughts such as ‘I give my mobile phone more priority than clothes and food,’ ‘I feel unsettled when I forget to take my mobile phone with me,’ ‘I would rather lose my wallet or purse than my mobile phone,’ and so forth. This is what Brown described as the cognitive component of behavioural addiction, in that the activity dominates the person's thoughts (Brown, Citation1993, Citation1997). This is also consistent with a previous study that found adolescents spent more time communicating by instant messaging to have a higher incidence of compulsive Internet use after 6 months (van den Eijnden, Meerkerk, Vermulst, Spijkerman, & Engels, Citation2008). The suggested three‐factor model of the MPDQ may make the measure useful as a screening tool in the assessment of mobile phone addiction. It is because it assesses both behaviour and cognitions.

Screening tool for mobile phone addiction

In the current study 16.90% of the students fell in the high‐dependency category, with the rate being 13.80% and 22.70% for boys and girls, respectively. When the more stringent criterion of exceeding the mean +2 SDs was used, 3.41% of the sample would be classified in the category of mobile phone addiction.

The MPDQ is suggested as a screening tool for mobile phone addiction. Similar to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th edition, Text Revision; DSM‐IV TR) criteria for substance dependence (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2000), symptoms such as euphoria, tolerance, withdrawal, compulsive behaviour, and obsessive thinking and thoughts are symptomatic of mobile phone dependence, as assessed by the MPDQ (Toda et al., Citation2004). The prevalence rate of mobile phone addiction is similar to the prevalence rate of Impulse Control Disorders 1–3% (Hospital Authority, Citation2011) and of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) 2.3% in the USA (Right Diagnosis, Citation2013). This provides strong evidence of the MPDQ's utility as a screening tool to identify students in the category of mobile phone addition.

Gender gap in mobile phone dependency

The means and medians of girls’ scores for the three psychological factors were higher than those of the boys. These results are consistent with prior research showing that girls tended to express their feelings by texting messages and talking to other people using their mobile phone; more girls than boys felt that they would rather lose their wallet than their mobile phone, and they felt more unsettled than boys did when they did not take their mobile phone with them (Kamibeppu & Sugiura, Citation2005). Another study showed that instant messaging was positively related to later compulsive Internet use for girls but not boys (van den Eijnden et al., Citation2008). The gender gap in mobile phone dependency is further confirmed.

Mobile phone use in youths’ everyday lives

The results suggest that youths in Hong Kong tend to use the mobile phone to maintain a close relationship and strong ties with parents (De Gournay, Citation2002). Nearly 70% of calls were related to family, and over 80% were made to call their parents to report their routines/schedules. These results are consistent with earlier research showing that students are willing to receive calls from parents and make calls to parents, and they are used to accepting parents’ mobile monitoring of their activities (Kopomaa, Citation2000; Ling, Citation2004; Oksman & Rautiainen, Citation2002; Rakow & Navarro, Citation1993).

They believed that using a mobile phone can strengthen their social ties with friends (Park, Citation2005). One interesting finding in the present study was that students in Hong Kong like to use the mobile phone to ask for tutoring from the teacher, termed mobile tutoring. This finding is consistent with a previous study that compulsive Internet use by adolescents needs to have a solid support structure sustained by social networking and instant messaging (Thorsteinsson & Davey, Citation2014).

There were clear differences in the pattern of mobile phone usage by students in the dependency and non‐dependency groups. About 8–12% of students in the dependency group sent ‘whatsApp’ and made and received calls more than 100 times daily. By contrast, sociable students may use the mobile phone mail more effectively to widen their interpersonal relations (Kamibeppu & Sugiura, Citation2005). Students from the non‐dependency group may have a choice to accept or avoid their friends’ and parents’ calls (Green, Citation2001; Ling, Citation2004; Matsuda, Citation2005; Rakow & Navarro, Citation1993). However, students from the dependency group obsessively think about making calls or texting messages to other people to maintain close relationships with friends. They would compulsively check their mobile phone for messages in and out.

Research Limitations

Lack of concurrent validity of the MPDQ

Investigations into the concurrent validity of the MPDQ with established measures of compulsive Internet use (e.g., Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS), Meerkerk, van den Eijnden, Vermulst, & Garetsen, Citation2007) and anxiety (e.g., Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale (DASS), Lovibond & Lovibond, Citation1995) are encouraged to identify teenagers’ compulsive behaviour and anxiety.

In addition, this assessment system can assist with establishing continuity between the home and self by providing cross‐informant ratings of teenagers’ mobile phone dependency, such as parents’ ratings (Nelson et al., Citation2012).

Lastly, this study exclusively examined the cross‐sectional association between mobile phone dependency and everyday life. As suggested by Kraut et al. (Citation2002), negative short‐term effects may dissipate over a longer period of time.

Future Directions for Consideration

Most kids are not dependent, and for these kids, there could be many ways to make use of their already established patterns of phone use. At the same time, the results have implications for helping the small number of students who are dependent.

A longitudinal design is suggested to investigate the long‐term effects of mobile phone dependency on the social development of adolescents.

Research implications

Mobile counselling to students

The mobile phone subscription penetration rate is 201.1% in Hong Kong (Office of the Communications Authority, The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, Citation2011). Youths are accustomed to using the mobile phone to communicate with friends, teachers, and parents, and to connect to the outside world. Nowadays, the mobile phone serves not only a communication function, but also other functions, such as providing career information, counselling, tutoring, and coaching to students. Mobile counselling could be beneficial to students who could see the counsellor in familiar surroundings when necessary. The development of mobile counselling ‘Apps’ is encouraged to provide stress relief, time management strategies, and effective social skills to students.

Mobile tutoring to students

Almost 100% of the junior high school students in the focus group interview would call their teachers for tutoring assignments and homework. A mobile tutoring ‘App’ can be developed to provide peer tutoring or coaching in class, building up a learning network among students. The proposed tutoring ‘App’ is something like remote e‐learning because the mobile phone is convenient and handy. It is believed students will feel more comfortable and find it more convenient to ask peers and teachers questions about assignments and homework using the mobile phone.

Impacts on other psychological attributes

The present study is mostly about typical teens, not much on addicted teens. It is advised that the impacts of mobile phone addiction on other psychological constructs, such as self‐concept, social skills, social integration, ethical conduct, and so forth, be investigated. The findings will inform the Government's efforts to generate a guideline to help people with mobile phone addiction.

Conclusion

Mobile phone dependency has become increasingly prominent as one of popular youth culture's preoccupations and is considered an important dimension for understanding teens’ everyday life. The current study suggests a reliable, valid, and clinical and cultural relevance measure to assess and identify psychological factors making up mobile phone dependency among the Chinese population. Results showed that the original measure is applicable to the Chinese student population. At the same time, several patterns of results exemplified the Chinese perspective. These results lay the foundation for further investigation of Chinese youth perspectives on mobile phone addiction and provide a validated measure to pursue this line of research.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM‐IV‐TR. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

- Brown, R. I. (1993). Some contributions of the study of gambling to the study of other. In W. R. Eadington & J. A. Cornelius (Eds.), Gambling behavior and problem gambling (pp. 241–272). Reno: University of Nevada.

- Brown, R. I. (1997). A theoretical model of the behavioural addictions—Applied to offending. In J. E. Hodge, M. Mcmurran, & C. R. Hollin (Eds.), Addicted to crime? (pp. 13–65). Chichester: John Wiley.

- Brown, R. P., Budzek, K., & Tamborski, M. (2009). On the meaning and measure of narcissism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35, 951–964.

- Byrne, B. M. (2006). Structural equation modeling with EQS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Castells, M., Fernandez‐ardevol, M., Qiu, L. C., & Sey, A. (2007). Mobile communication and society: A global perspective. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Cellular News. (2006, November 22). SMSing under the dinner table. Retrieved April 1, 2013, from Cellular News: http://www.cellular‐news.com/story/20531.php

- Charlton, J. P. (2002). A factor‐analytic investigation of computer ‘addiction’ and engagement. British Journal of Psychology, 93, 329–344.

- Chen, Y. F., & Katz, J. E. (2009). Extending family to school life: College students’ use of the mobile phone. International Journal of Human‐Computer Studies, 67, 179–191.

- Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. W. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 10, 1–9.

- De gournay, C. (2002). Pretense of intimacy in France. In Y. F. Chen & J. E. Katz (Eds.), Perpetual contact: Mobile communication, private talk, public performance (pp. 193–205). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fox, K. (2006). Society: The new garden fence. London: Carphone Warehouse & London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Gergen, K. J. (2002). The challenge of absent presence. In J. E. Katz & M. Aakhus (Eds.), Perpetual contact (pp. 227–241). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Green, N. (2001). Who's watching whom? Monitoring and accountability in mobile relations. In B. Brown, N. Green, & R. Harper (Eds.), Wireless world: Social and interactional aspects of the mobile age (pp. 32–45). London: Springer.

- Griffiths, M. (1999). Internet addiction, fact or fiction? The Psychologist, 12, 246–250.

- Hospital Authority. (2011). Hospital Authority metal health service plan for adults 2010–2015. Hong Kong: Hospital Authority.

- Ito, M. (2005). Mobile phones, Japanese youth, and the re‐placement of social contact. Mobile Communications, 31, 131–148.

- Kamibeppu, K., & Sugiura, H. (2005). Impact of the mobile phone on junior high‐school students’ friendships in the Tokyo metropolitan area. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 8, 121–130.

- Katz, J. E., & Askhus, M. (2002). Perpetual contact: Mobile communication, private talk, public performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kopomaa, T. (2000). The city in your pocket: Birth of the mobile information society. Helsinki: University Press.

- Kraut, R., Kiesler, S., Boneva, B., Cummings, J., Helgeson, V., & Crawford, A. (2002). Internet paradox revisited. Journal of Social Issues, 58(1), 49.

- Ling, R. (2004). The mobile connection: The cell phone's impact on society. San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann.

- Ling, R., & Yttri, B. (2006). Control, emancipation, and status: The mobile telephone in teens’ parental and peer relationship. In R. Kraut, M. Brynin, & S. Kiesler (Eds.), Computer, phones, and the Internet: Domesticating information technology (pp. 219–234). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Little, T. D. (1997). Mean and covariance structures (MACS) analyses of cross cultural data: Practical and theoretical issues. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 32, 53–76.

- Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behavior Research and Therapy, 33, 335–343.

- Matsuda, M. (2005). Mobile communication and selective sociality. In M. Ito, D. Okabe, & M. Matsuda (Eds.), Personal, portable, pedestrian: Mobile phones in Japanese life (pp. 123–142). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Meerkerk, G.‐J., van den Eijnden, R. J. J. M., Vermulst, A. A., & Garetsen, H. F. L. (2007). The relationship between personality, psychosocial wellbeing and compulsive internet use: The internet as cyber Prozac? In G.‐J. Meerkerk (Ed.), Pwned by the internet: Explorative research into the cause and consequences of compulsive internet use (pp. 86–99). Rotterdam: IVO.

- Nelson, C., Hartling, L., Campbell, S., & Oswald, A. E. (2012). The effects of audience response systems on learning outcomes in health professions education. A BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 21. Medical Teacher, 34(6), 386–405.

- Office of the Communications Authority, The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. (2011, March 31). Telecommunication Indicators in Hong Kong for the fiscal year ending 31 March 2011. Retrieved April 1, 2013, from Office of the Communications Authority: http://www.ofca.gov.hk/en/media_focus/data_statistics/indicators/index.html

- Oksman, V., & Rautiainen, P. (2002). Perhaps it is a body part. How the mobile phone became an organic part of the everyday lives of Finnish children and adolescents. In J. E. Katz (Ed.), Machines that become us (pp. 293–308). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

- Orford, J. (2001). Addiction as excessive appetite. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 96, 15–31.

- Park, W. K. (2005). Mobile phone addiction. In R. Ling & P. E. Pedersen (Eds.), Mobile communications: Re‐negotiation of the social sphere (pp. 253–272). London: Springer.

- Persson, A. (2001). Intimacy among strangers: On mobile telephone calls in public places. Journal of Mundane Behavior, 2(3), 309–316.

- Rakow, L. F., & Navarro, V. (1993). Remote mothering and the parallel shift: Women meet the cellular telephone. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 10, 144–157.

- Right Diagnosis. (2013, March 31). Statistics about obsessive‐compulsive disorder. Retrieved April 1, 2013, from Right Diagnosis: http://www.rightdiagnosis.com/o/obsessive_compulsive_disorder/stats.htm

- Sawhney, N., & Gomez, H. (2000, September). Communication patterns in domestic life: Preliminary ethnographic study. Retrieved April 1, 2013, from CiteSeerx: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download;jsessionid=9127799FDC3BAEE1E127A7C3BAD119DF?doi=10.1.1.25.2281&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Shaffer, H. J. (1996). Understanding the means and objects of addiction: Technology, the Internet, and gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 12, 461–469.

- Srivastava, L. (2005). Mobile phones and the evolution of social behaviour. Behaviour and Information Technology, 24, 111–129.

- The Carphone Warehouse. (2006). The mobile life report 2006: How mobile phones change the way we live. Retrieved April 1, 2013, from http://iis.yougov.co.uk/extranets/ygarchives/content/pdf/CPW060101004_1.pdf

- The Standard. (2010, August 3). Youngsters cannot ignore mobile call. Retrieved April 1, 2013, from The Standard: http://www.thestandard.com.hk/news_detail.asp?pp_cat=11&art_id=101258&sid=29119749&con_type=1&d_str=20100803&isSearch=1&sear_year=2010

- Thorsteinsson, E. B., & Davey, L. (2014). Adolescents’ compulsive Internet use and depression: A longitudinal study. Open Journal of Depression, 3, 13–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.4236/ojd.2014.31005

- Toda, M., Monden, K., Kubo, K., & Morimoto, K. (2004). Cellular phone dependence tendency of female university students. Japanese Journal of Hygiene, 59, 383–386.

- Toda, M., Monden, K., Kubo, K., & Morimoto, K. (2006). Mobile phone dependence and health‐related lifestyle of university students. Social Behavior and Personality, 34, 1277–1284.

- Toda, M., Ezoe, S., Nishi, A., Mukai, T., Goto, M., & Morimoto, K. (2008). Mobile phone dependence of female students and perceived parental rearing attitudes. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 36, 765–770.

- van den Eijnden, R. J. J. M., Meerkerk, G.‐J., Vermulst, A. A., Spijkerman, R., & Engels, R. C. M. E. (2008). Online communication, compulsive Internet use, and psychosocial well‐being among adolescents: A longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 44, 655–665. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0012‐1649.44.3.655