Abstract

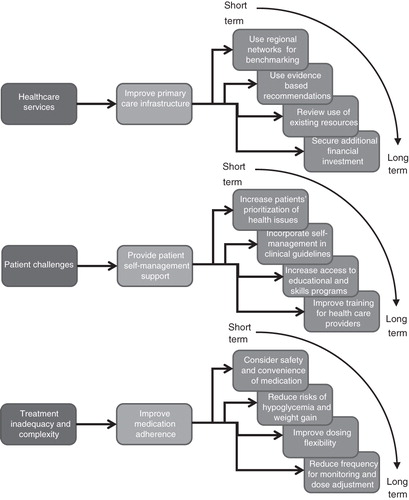

Insulin initiation, which was traditionally the province of specialists, is increasingly undertaken by primary care. However, significant barriers to appropriate and timely initiation still exist. Whilst insulin is recognized as providing the most effective treatment in type 2 diabetes, it is also widely considered to be the most challenging and time consuming. This editorial identifies that the organization of existing healthcare services, the challenges faced by patients, and the treatments themselves contribute to suboptimal insulin management. In order to improve future diabetes care, it will be necessary to address all three problem areas: (1) re-think the best use of existing human and financial resources to promote and support patient self-management and adherence to treatment; (2) empower patients to participate more actively in treatment decision making; and (3) improve acceptance, persistence and adherence to therapy by continuing to refine insulin therapy and treatment regimens in terms of safety, simplicity and convenience. The principles discussed are also applicable to the successful management of any chronic medical illness.

Introduction

Primary care practitioners are increasingly being called upon to manage chronic medical illnesses such as type 2 diabetes. It is a progressive disease requiring periodic treatment intensification from lifestyle modifications and oral anti-diabetes agents, to insulin therapy. Insulin initiation was traditionally undertaken by specialists, but owing to the growing number of patients, access to specialist care is becoming more limited to patients with complications and/or particularly poor glycemic controlCitation1–3. In contrast, the role of primary care practitioners in managing insulin has increasedCitation1,Citation4.

Despite improvements in lipid and blood pressure control in recent years, achieving good glycemic control remains challengingCitation5–7. Significant barriers to appropriate and timely insulin initiation still existCitation8–10, and the prospect of intensifying to more complex insulin regimens and the need for more frequent blood glucose monitoring may be daunting for both patients and health care professionals alike. Patients’ ability to adhere to therapy is known to be a significant problem in the treatment of chronic illnesses, and particularly in conditions such as diabetes, where patients may be asymptomatic for many years, and only develop significant morbidity in the longer term.

In many countries there is political interest in continuing to move the care of type 2 diabetes into primary care and, in so doing, reduce healthcare management costs. Insulin is recognized as providing the most effective treatment for many people with type 2 diabetes, but is also widely considered to be the most challenging and time consumingCitation1,Citation11. This editorial outlines the areas of diabetes care relevant to insulin therapy that need to be addressed in order to successfully manage the growing number of patients with this condition, and, where possible, to identify non-disease specific solutions so as to improve cost-effectiveness, implementation and sustainability in primary care ().

The content represents the consensus opinion of members of a multi-professional expert panel within specialist and community diabetes care which convened to identify, discuss and suggest potential solutions to problems with insulin management in people with diabetes.

Current status of type 2 diabetes

Type 2 diabetes is predicted to reach epidemic proportions, with a global increase in prevalence of 65% over the next 20 yearsCitation12–14. It is already the sixth most commonly registered outpatient diagnosis, and the fourth most commonly diagnosed chronic condition (10%), after hypertension (24%), arthritis (13%) and dyslipidemia (12%)Citation15. Using HbA1c criteria, the prevalence of diagnosed and undiagnosed adult diabetes in the USA is estimated to be 9.6%, and at any one time an additional 3.5% of the population is at high risk of developing diabetesCitation16. In people aged ≥65 years of age, the proportion with diagnosed or undiagnosed diabetes is estimated at 27%Citation17, and in this older age group, the frequency of consultations related to diabetes rose by 45% in the period 1998–2008Citation18.

In addition, a large proportion of patients are still not reaching recommended glycemic targets. In the UK, there was a 0.1% relative improvement in HbA1c in patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes treated with insulin between 2001 and 2007Citation5. This compared to reductions in total cholesterol and blood pressure of 15% and 29%, respectively. In Canada and the US, the proportion of patients not achieving HbA1c<7% is estimated to be between 43 and 49%Citation19–21; and up to two thirds of patients managed in primary care have HbA1c>7.0%Citation6,Citation22.

Macrovascular complications such as myocardial infarction and stroke remain the leading causes of death in patients with diabetesCitation23. Diabetes also remains the most common cause of end stage renal disease, and the number of patients requiring dialysis continues to growCitation24. Good long term glycemic control, particularly in the early years of the disease, is essential to reduce the risk of microvascular and macrovascular complications. Treatment intensification, however, commonly occurs when patients reach HbA1c levels far in excess of recommended treatment targetsCitation25. This means that patients may wait many years before receiving appropriate insulin therapy, and that most patients with type 2 diabetes may spend the majority of the duration of their disease with suboptimal glycemic controlCitation26–28. Conversely, timely transition to insulin and a more rapid intensification of treatment may delay the onset of diabetes complicationsCitation29.

Problems in diabetes care

Clinical inertia, defined as ‘recognition of the problem, but failure to act’ is a principal cause of poor glycemic controlCitation30–32. There are many reasons for this which can relate to the provision of healthcare services, the challenges faced by patients and/or the treatments used.

Healthcare services

In clinical trials of basal insulin treatment, there is a close correlation between increasing patient contact with healthcare services and the extent to which HbA1c is reducedCitation33. Greaves et al.Citation11 identified that, in order to support insulin conversion, health care professionals wanted more education and support including: hands-on experience, clear protocols for implementing insulin conversion, and availability of local help and support services (e.g. helplines). Access to existing educational programs is often limited by local resource issues. Inconsistent training means that vital skills, such as injection technique and self-monitoring, often remain poorCitation34.

There is a clear role for guidelines in laying out principles of diabetes care and issuing pragmatic therapeutic strategies for health care providers. There remains a lack of consensus, however, between the international and national guidelines regarding glycemic targets (ranging between <6.5%Citation35 to <7.5%Citation36) and recommendations for optimal diabetes managementCitation36–39. For example, although all of the guidelines acknowledge reduced risk of hypoglycemia and improved convenience from the use of basal insulin analogues compared with human insulin preparationsCitation40, recommendations for use in clinical practice range from complete avoidance of human insulin to use of human insulin in the first instanceCitation35,Citation36. The absence of international consensus on clinical guidance may account for a proportion of the national variations in treatmentCitation41,Citation42.

Patient challenges

Patient knowledge is necessary to implement effective self-management and is increasingly recognized as a crucial element to achieving targets in diabetes and other chronic medical illnessCitation43. Aspects of self-management include attention to nutrition, exercise, medication, self-monitoring, problem solving, risk reduction and psychosocial adjustmentCitation44. In addition, misconceptions about the disease and treatment progression result in insulin treatment being seen as a personal failure, rather than as a necessary and expected therapy due to the progressive nature of the diseaseCitation12.

Adherence to therapy is also crucial to achieving good control and avoidance of life-threatening complicationsCitation45,Citation46. The extent of medication non-adherence to oral anti-diabetes agents is reported to be between 7% and 64%Citation47. The same appears to be true of insulin therapy, where average adherence is approximately 70%Citation46. Side effects such as hypoglycemia and weight gain will influence therapy adherenceCitation48. In a study of oral anti-diabetes therapy, there was a 28% increase in medication non-adherence for each treatment tolerability issue such as signs/symptoms of hypoglycemia and weight gainCitation49. The complexity of treatment regimens may also exacerbate adherence issues. Adherence to oral agents decreased from 79% with a single agent to 38% with three agentsCitation50. Peyrot et al.Citation48 reported that almost 60% of patients miss injections, and that 20% do so on a regular basis, with worse overall adherence associated with the restrictiveness of the insulin regimen.

Insulin regimens, in particular, require patients to dose at specific times of the day, in relation to food, exercise, and the previous doseCitation51. Whilst basal insulin administration is perhaps the least restrictive, some regimens are not easily adapted to changes in routine. Inflexible dosing is often cited as a reason for missing dosesCitation48. A recently conducted survey identified that at least one third of patients had missed an average of three doses of insulin in the previous monthCitation52. The majority of physicians thought that the number of missed doses per month was closer to six. Patients reported that the main reasons for missing doses were changes in the normal daily routine (40%), being too busy (37%), difficulty with taking the insulin at the prescribed time (31%) or simply forgetting (18%).

Treatment inadequacy and complexity

Despite the fact that insulin remains the most efficacious glucose-lowering therapy, and is perceived by health care professionals to provide considerable patient benefitsCitation11, the delay in initiation is usually longer than at any other stage of diabetes treatment intensificationCitation25. Indeed, insulin treatment complexity and the demand that this places on the existing healthcare infrastructure means that insulin is often used as a last resort. In addition, insulin injection and titration are cumbersome and time intensive for both the patient and physician. Patient self-titration has been shown to be at least as effective and safe as physician-directed titration in controlled trialsCitation53–55, and is likely to be more cost-effective in clinical practice. However, this requires patients to be skilled in performing blood glucose monitoring, dose calculation and insulin injection. Ultimately, whichever titration algorithms are selected, the need for continuous active monitoring and dose adjustment is one of the major drawbacks of current insulin therapy. Treatment success with currently available insulin therapies may also be limited by patient dissatisfaction with the need for frequent, expensive and painful blood glucose monitoringCitation56.

At present, the majority of patients do not feel empowered to manage their diabetes. In a recent survey exploring attitudes to insulin therapy, two thirds of patients thought that their diabetes controlled their lives and that treatment regimens were too restrictive, whilst 34% felt their diabetes was not controlled in terms of blood glucose, hypoglycemia or lifestyleCitation52. Hypoglycemia remains a significant barrier to achieving good glycemic control, particularly in patients with a longer duration of diabetes, and in elderly patients where hypoglycemia can result in significant co-morbidityCitation57–59. Polonsky et al.Citation9 also reported consistently negative patient beliefs regarding insulin therapy, the most frequent including therapy restrictiveness, and problematic hypoglycemia.

Optimizing future diabetes care

In order to improve future diabetes care, it will be necessary to address all three problem areas, namely the healthcare service (by improving primary care infrastructure), patient challenges (through enhancing self-management), and treatment inadequacy (by improving medication adherence and improving drug tolerability).

Improving primary care infrastructure

The existing primary care structure is overstretched and under-resourced and, as a consequence, commonly fails to optimally provide for patients with chronic medical illness. Chronic care models, whereby prepared and proactive health care teams engage regularly with informed and activated patients, have been successfully implemented in settings with minimal resourcesCitation44.

At a local level, changes to infrastructure should be aimed at allowing more opportunity for patients to interact with healthcare services. This can be accomplished by decentralizing some aspects of care (for example the promotion and support of patient self-management and adherence to therapy) away from physicians to involve allied health care providers, lay staff, volunteers and family members. Promoting adherence to treatment need not necessarily be limited to prescribers, and trained non-physician personnel could be effective and more easily accessibleCitation60. At a regional level, benchmarking and sharing of best practices have been shown to improve treatment outcomesCitation61,Citation62 and help practices determine the best use of limited resources. At national and international levels, professional organizations and payers need to work together to reach a consensus on the goals of treatment, and close the current gap between guidelines and clinical practiceCitation63. Guidelines should consider not only the efficacy and safety of individual treatments, but also patient willingness to initiate and persist in the treatment and their ability to adhere to therapy.

Providing patient self-management support

Patients with chronic medical illnesses such as diabetes have an inevitable conflict between their desire to lead a normal life and their efforts to preserve healthCitation64. Enhancing patient self-management by involving patients in treatment decisions improves glycemic control, treatment adherence and quality of lifeCitation65–67. Engaging patients in developing their own management plans also assists the health care provider in understanding where the disease and the treatment fit in the wider context of the patient’s life. In this collaborative environment, communication skills and the ability to foster behavioral change are of paramount importanceCitation64,Citation68–70.

Patients must also be sufficiently knowledgeable to be able to engage in treatment decision making. Information may be provided verbally during a consultation, and/or in the form of reading materials, web-based applications or structured educational programs. Although the latter are often considered the gold standard approach, these are also the most resource intensive. In recent years, there has been a focus on developing web-based self-management applications which may ultimately become much more widely accessible. One example of a web-based solution is in the treatment of depression in diabetesCitation71. Although attrition rates are quite high in this study, recruitment and follow-up by medical staff may increase adherence to such programs. The treatment of depression in association with chronic medical illness is also an example where less disease specific tools may simplify primary care management and increase cost-effectiveness through economies of scale. Care should also be taken not to overload patients with information, however, as this has been shown to negatively affect decision makingCitation64.

Improving medication adherence

The assessment of patient medication adherence by primary care physicians is an important prognostic marker for mortality in patients with type 2 diabetesCitation72. Patient understanding of treatments improves therapy adherenceCitation73, and even practical procedural information related to a planned health care visit has been shown to reduce rates of clinic non-attendanceCitation74. Nevertheless, training on how to maximize patient adherence to treatment, as well as identifying and managing the problem is needed. Only a small minority of health care providers have training in counseling patients with non-adherenceCitation75, and so whilst poor treatment adherence is recognized as a key contributor to poor outcomes, most health professionals feel unable to address this important barrier in daily practiceCitation10. A recently published study of strategies employed by physicians to identify and treat non-adherence, suggested that educational approaches were preferred over behavioral approaches and counseling despite the fact that education alone is known to be insufficient in establishing or maintaining good adherenceCitation75.

If adherence is to improve, then more has to be done to understand patient priorities, and how to make treatments more acceptableCitation76. Historically, the approach to improving patient adherence to long-term treatment has been to simplify the treatment regimen by reducing the frequency of dosing, and combining commonly prescribed agents into a single formulationCitation47,Citation77,Citation78. In a systematic review of adherence to oral agents, reduced dosing frequency, monotherapy versus polytherapy, and conversion from monotherapy or polytherapy to single combination treatments were all successful in improving adherenceCitation47. Other successful strategies include provision of more detailed patient information, counseling, reminders and close follow-up, all of which involve more frequent healthcare interaction and consume precious resourcesCitation78. Employing some of these strategies to insulin therapy in addition to addressing other patient and physician treatment ideals (e.g. reduced risk of treatment side effects, easier and more convenient dosing, and reduced requirement for blood glucose monitoring), may be one of the more effective ways to reduce barriers to insulin therapy and increase long-term insulin adherenceCitation79,Citation80.

Improving insulin use in primary care

Insulin is a vital tool in the treatment of diabetes and more must be done to identify and address the issues that prevent insulin being used in an optimal way. This review has identified three areas that need to be addressed in order to optimize the use of insulin: (1) primary care infrastructure, (2) encouraging patients to take ownership in managing their disease, and (3) improving treatment adherence.

Additional financial investment in primary care with the specific aim of improving support for patients with chronic medical illness is important. National primary care organizations should continue to lobby for this investment. Addressing fundamental shortages in the number of specialist and allied health care personnel is a mid to long-term strategy, however, and is unlikely to have significant impact on diabetes care by 2015. In the immediate short-term, individual practices need to review their use of existing human and logistical resources (including affiliations to specialist and community networks) so as to enhance the frequency and quality of patient–provider interactions. Optimizing the clarity of communication and processes that encourage patient self-management need not be resource intensive, but do require different competenciesCitation81, and these need to be reflected in clinical guidelines. There should also be a focus on applying evidenced based recommendations where possible, which includes not just recommendations concerning therapy selection, but also skills such as injection techniqueCitation34.

Lastly, by continuing to develop new insulin treatments that have attributes desired by patients and physicians this may help to break down the barriers to insulin initiation and intensification, as well as improve patient adherence. Reducing the risks of hypoglycemia, weight gain, and the complexity of treatment would be expected to facilitate initiation and adherence to insulin therapy. The broader implications of drug safety and convenience, both with respect to individual treatments and treatment strategies, needs to be more carefully considered in future consensus guidelines.

Conclusions

Whilst the authors of this paper have focused on the treatment of diabetes, the principles of re-evaluating primary healthcare infrastructure, supporting patient self-management and improving therapy adherence applies to the successful management of any chronic medical illness. In this way, infrastructural changes, self-management training for patients and multidisciplinary teams, and the development of patient support networks can also potentially benefit from economy of scale (for example, by making self-management resources, training and support less disease specific). There is clearly a need to review the way in which diabetes is managed, and to identify which infrastructural changes and additional resources are required to achieve long-term improvements in quality of life, and reductions in mortality and healthcare costs. Improvements in therapy in terms of safety, simplicity and convenience may also play a key role in improving acceptance, persistence and adherence to therapy.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This paper represents the consensus opinion of a multidisciplinary team of experts in diabetes care who met in November 2010 to identify, discuss and put forward solutions to problems with insulin management in patients with diabetes. The meeting and medical writing assistance was organized and funded by Novo Nordisk.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

The authors disclose the following consulting income, honoraria, and/or grant support: C.T. – Novo Nordisk; W.J. – Novo Nordisk; A.H.B. – Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi Aventis; S.B. – Novo Nordisk; S.G. – Novo Nordisk; D.H. – BD, BMS/AZ, Eli Lilly, Lifescan, MSD, Novo Nordisk, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, and Takeda; E.M. – Amylin, BMS/AZ, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk; M.P. – Amylin, Animas, CPEX, Eli Lilly, Genentech, Healthy Interactions, MannKind, Medtronic, Novo Nordisk and Patton Medical Devices; D.S. – Novo Nordisk; P.M.S.-D. – Berlin Chemie, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi Aventis.

Acknowledgements

This Diabetes Consensus Group comprised Stephen Brunton, Etie Moghissi, Debbie Hicks, Christine Tobin, Stephen Gough, Weng Jianping, Doron Schneider, Petra Maria Schumm-Draeger, Mark Peyrot, and Tony Barnett. All participants of the meeting have contributed directly to preparing this manuscript and/or reviewing the manuscript for scientific and historical accuracy. The authors would like to thank Christopher M. Burton from Point Of Care Medical Consulting for providing medical writing assistance.

References

- van Avendonk MJ, Gorter KJ, van den Donk M, et al. Insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes is no longer a secondary care activity in the Netherlands. Prim Care Diabetes 2009;3:23-8

- Goyder EC, McNally PG, Drucquer M, et al. Shifting of care for diabetes from secondary to primary care, 1990–5: review of general practices. BMJ 1998;316:1505-6

- Khunti K, Ganguli S. Who looks after people with diabetes: primary or secondary care? J R Soc Med 2000;93:183-6

- Brunton S, Carmichael B, Funnell M, et al. Type 2 diabetes: the role of insulin. J Fam Pract 2005;54:445-52

- Currie CJ, Gale EA, Poole CD. Estimation of primary care treatment costs and treatment efficacy for people with Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes in the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007. Diabet Med 2010;27:938-48

- Dale J, Martin S, Gadsby R. Insulin initiation in primary care for patients with type 2 diabetes: 3-year follow-up study. Prim Care Diabetes 2010;4:85-9

- McCrate F, Godwin M, Murphy L. Attainment of Canadian Diabetes Association recommended targets in patients with type 2 diabetes: a study of primary care practices in St John's, Nfld. Can Fam Physician 2010;56:e13-e19

- Kunt T, Snoek FJ. Barriers to insulin initiation and intensification and how to overcome them. Int J Clin Pract Suppl 2009;164:6-10

- Polonsky WH, Fisher L, Guzman S, et al. Psychological insulin resistance in patients with type 2 diabetes: the scope of the problem. Diabetes Care 2005;28:2543-5

- Peyrot M, Rubin RR, Lauritzen T, et al. Psychosocial problems and barriers to improved diabetes management: results of the Cross-National Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and Needs (DAWN) Study. Diabet Med 2005;22:1379-85

- Greaves CJ, Brown P, Terry RT, et al. Converting to insulin in primary care: an exploration of the needs of practice nurses. J Adv Nurs 2003;42:487-96

- Burke JP, Williams K, Gaskill SP, et al. Rapid rise in the incidence of type 2 diabetes from 1987 to 1996: results from the San Antonio Heart Study. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:1450-6

- Fox CS, Pencina MJ, Meigs JB, et al. Trends in the incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus from the 1970s to the 1990s: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2006;113:2914-18

- Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, et al. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care 2004;27:1047-53

- Hsiao CJ, Cherry DK, Beatty PC, et al. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2007 Summary. National Health Statistics Reports 2010;27:1-32

- Cowie CC, Rust KF, Byrd-Holt DD, et al. Prevalence of diabetes and high risk for diabetes using A1C criteria in the U.S. population in 1988–2006. Diabetes Care 2010;33:562-8

- National Diabetes Statistics. 2007. Available at: http://diabetes.niddk.nih.gov/dm/pubs/statistics/index.htm [Last accessed 25 February 2011].

- Cherry D, Lucas C, Decker SL. Population Aging and the Use of Office-based Physician Services. NCHS Data Brief. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published August 2010. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db41.pdf

- Hoerger TJ, Segel JE, Gregg EW, et al. Is glycemic control improving in U.S. adults?. Diabetes Care 2008;31:81-6

- Dodd AH, Colby MS, Boye KS, et al. Treatment approach and HbA1c control among US adults with type 2 diabetes: NHANES 1999–2004. Curr Med Res Opin 2009;25:1605-13

- Harris SB, Ekoe JM, Zdanowicz Y, et al. Glycemic control and morbidity in the Canadian primary care setting (results of the diabetes in Canada evaluation study). Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2005;70:90-7

- Fox KM, Gerber Pharmd RA, Bolinder B, et al. Prevalence of inadequate glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes in the United Kingdom general practice research database: a series of retrospective analyses of data from 1998 through 2002. Clin Ther 2006;28:388-95

- Nelson KM, Boyko EJ, Koepsell T. All-cause mortality risk among a national sample of individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care 2010;33:2360-4

- International Diabetes Federation. Diabetes Atlas. 2011. Available at: http://da3.diabetesatlas.org/index3eec.html [Last accessed 25 February 2010]

- Calvert MJ, McManus RJ, Freemantle N. Management of type 2 diabetes with multiple oral hypoglycaemic agents or insulin in primary care: retrospective cohort study. Br J Gen Pract 2007;57:455-60

- Davis TM, Davis Cyllene Uwa Edu Au WA, Bruce DG. Glycaemic levels triggering intensification of therapy in type 2 diabetes in the community: the Fremantle Diabetes Study. Med J Aust 2006;184:325-8

- Ringborg A, Lindgren P, Yin DD, et al. Time to insulin treatment and factors associated with insulin prescription in Swedish patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab 2010;36:198-203

- Rubino A, McQuay LJ, Gough SC, et al. Delayed initiation of subcutaneous insulin therapy after failure of oral glucose-lowering agents in patients with Type 2 diabetes: a population-based analysis in the UK. Diabet Med 2007;24:1412-18

- Simons WR, Vinod HD, Gerber RA, et al. Does rapid transition to insulin therapy in subjects with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus benefit glycaemic control and diabetes-related complications? A German population-based study. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2006;114:520-6

- Zafar A, Davies M, Azhar A, et al. Clinical inertia in management of T2DM. Prim Care Diabetes 2010;4:203-7

- Ziemer DC, Miller CD, Rhee MK, et al. Clinical inertia contributes to poor diabetes control in a primary care setting. Diabetes Educ 2005;31:564-71

- Hsu WC. Consequences of delaying progression to optimal therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes not achieving glycemic goals. South Med J 2009;102:67-76

- Swinnen SG, Devries JH. Contact frequency determines outcome of basal insulin initiation trials in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2009;52:2324-7

- Frid A, Hirsch L, Gaspar R, et al. New injection recommendations for patients with diabetes. Diabetes Metab 2010;36(Suppl 1):S3-18

- Rodbard HW, Jellinger PS, Davidson JA, et al. Statement by an American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology consensus panel on type 2 diabetes mellitus: an algorithm for glycemic control. Endocr Pract 2009;15:540-59

- CG87 – Type 2 Diabetes – Newer Agents. Royal College of Physicians, 2009

- Global Guideline for Type 2 Diabetes. International Diabetes Federation, 2005

- Canadian Diabetes Association 2008 clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of diabetes in Canada. Canadian Diabetes Association, 2008

- Woo V. Important differences: Canadian Diabetes Association 2008 clinical practice guidelines and the consensus statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetologia 2009;52:552-3

- Monami M, Marchionni N, Mannucci E. Long-acting insulin analogues versus NPH human insulin in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2008;81:184-9

- Alvarez GF, Mavros P, Nocea G, et al. Glycaemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in seven European countries: findings from the Real-Life Effectiveness and Care Patterns of Diabetes Management (RECAP-DM) study. Diabetes Obes Metab 2008;10(Suppl 1):8-15

- Fu AZ, Qiu Y, Davies MJ, et al. Treatment intensification in patients with type 2 diabetes who failed metformin monotherapy. Diabetes Obes Metab 2011;13:765-9

- Loveman E, Frampton GK, Clegg AJ. The clinical effectiveness of diabetes education models for Type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess 2008;12:1-116,iii

- Stroebel RJ, Gloor B, Freytag S, et al. Adapting the chronic care model to treat chronic illness at a free medical clinic. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2005;16:286-96

- Rhee MK, Slocum W, Ziemer DC, et al. Patient adherence improves glycemic control. Diabetes Educ 2005;31:240-50

- Donnelly LA, Morris AD, Evans JM. Adherence to insulin and its association with glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. QJM 2007;100:345-50

- Cramer JA. A systematic review of adherence with medications for diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004;27:1218-24

- Peyrot M, Rubin RR, Kruger DF, et al. Correlates of insulin injection omission. Diabetes Care 2010;33:240-5

- Pollack MF, Purayidathil FW, Bolge SC, et al. Patient-reported tolerability issues with oral antidiabetic agents: Associations with adherence; treatment satisfaction and health-related quality of life. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2010;87:204-10

- Rubin RR. Adherence to pharmacologic therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Med 2005;118(Suppl 5A):27S-34S

- Devries JH, Nattrass M, Pieber TR. Refining basal insulin therapy: what have we learned in the age of analogues? Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2007;23:441-54

- Data on file. The Global Attitudes of Patients and Physicians in Insulin Therapy (GAPP) survey. 17-11-2010

- Blonde L, Merilainen M, Karwe V, et al. Patient-directed titration for achieving glycaemic goals using a once-daily basal insulin analogue: an assessment of two different fasting plasma glucose targets – the TITRATE study. Diabetes Obes Metab 2009;11:623-31

- Meneghini L, Koenen C, Weng W, et al. The usage of a simplified self-titration dosing guideline (303 Algorithm) for insulin detemir in patients with type 2 diabetes – results of the randomized, controlled PREDICTIVE 303 study. Diabetes Obes Metab 2007;9:902-13

- Davies M, Storms F, Shutler S, et al. Improvement of glycemic control in subjects with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes: comparison of two treatment algorithms using insulin glargine. Diabetes Care 2005;28:1282-8

- Karter AJ, Ackerson LM, Darbinian JA, et al. Self-monitoring of blood glucose levels and glycemic control: the Northern California Kaiser Permanente Diabetes registry. Am J Med 2001;111:1-9

- Choudhary P, Amiel SA. Hypoglycaemia: current management and controversies. Postgrad Med J 2011;87:298-306

- Risk of hypoglycaemia in types 1 and 2 diabetes: effects of treatment modalities and their duration. Diabetologia 2007;50:1140-7

- Chelliah A, Burge MR. Hypoglycaemia in elderly patients with diabetes mellitus: causes and strategies for prevention. Drugs Aging 2004;21:511-30

- Russell ML, Insull W Jr, Probstfield JL. Examination of medical professions for counseling on medication adherence. Am J Med 1985;78:277-82

- Goderis G, Borgermans L, Grol R, et al. Start improving the quality of care for people with type 2 diabetes through a general practice support program: a cluster randomized trial. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2010;88:56-64

- Margeirsdottir HD, Larsen JR, Kummernes SJ, et al. The establishment of a new national network leads to quality improvement in childhood diabetes: implementation of the ISPAD Guidelines. Pediatr Diabetes 2010;11:88-95

- Kilpatrick ES, Das AK, Orskov C, et al. Good glycaemic control: an international perspective on bridging the gap between theory and practice in type 2 diabetes. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:2651-61

- Sevick MA, Trauth JM, Ling BS, et al. Patients with complex chronic diseases: perspectives on supporting self-management. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22(Suppl 3):438-44

- Aschner P, LaSalle J, McGill M. The team approach to diabetes management: partnering with patients. Int J Clin Pract Suppl 2007;157:22-30

- Serrano-Gil M, Jacob S. Engaging and empowering patients to manage their type 2 diabetes, Part I: a knowledge, attitude, and practice gap? Adv Ther 2010;27:321-33

- Cochran J, Conn VS. Meta-analysis of quality of life outcomes following diabetes self-management training. Diabetes Educ 2008;34:815-23

- Edwall LL, Danielson E, Ohrn I. The meaning of a consultation with the diabetes nurse specialist. Scand J Caring Sci 2010;24:341-8

- Hood KK, Rohan JM, Peterson CM, et al. Interventions with adherence-promoting components in pediatric type 1 diabetes: meta-analysis of their impact on glycemic control. Diabetes Care 2010;33:1658-64

- Parkin T, Skinner TC. Discrepancies between patient and professionals recall and perception of an outpatient consultation. Diabet Med 2003;20:909-14

- van Bastelaar KM, Pouwer F, Cuijpers P, et al. Web-based depression treatment for type 1 and type 2 diabetic patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2011;34:320-5

- Rothenbacher D, Ruter G, Brenner H. Prognostic value of physicians' assessment of compliance regarding all-cause mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes: primary care follow-up study. BMC Fam Pract 2006;7:42

- Wartman SA, Morlock LL, Malitz FE, et al. Patient understanding and satisfaction as predictors of compliance. Med Care 1983;21:886-91

- Hardy KJ, O'Brien SV, Furlong NJ. Information given to patients before appointments and its effect on non-attendance rate. BMJ 2001;323:1298-300

- Berben L, Bogert L, Leventhal ME, et al. Which interventions are used by health care professionals to enhance medication adherence in cardiovascular patients? A survey of current clinical practice. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2010;10:14-21

- van Dulmen S, Sluijs E, van Dijk L, et al. Furthering patient adherence: a position paper of the international expert forum on patient adherence based on an internet forum discussion. BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:47

- Hughes CM. Medication non-adherence in the elderly: how big is the problem? Drugs Aging 2004;21:793-811

- Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;2:CD000011

- Chapman RH, Kowal SL, Cherry SB, et al. The modeled lifetime cost-effectiveness of published adherence-improving interventions for antihypertensive and lipid-lowering medications. Value Health 2010;13:685-94

- McDonald HP, Garg AX, Haynes RB. Interventions to enhance patient adherence to medication prescriptions: scientific review. JAMA 2002;288:2868-79

- Jansink R, Braspenning J, van der Weijden T, et al. Primary care nurses struggle with lifestyle counseling in diabetes care: a qualitative analysis. BMC Fam Pract 2010;11:41