Abstract

Objective:

This narrative review describes the differential diagnosis of restless legs syndrome, and provides an overview of the evidence for the associations between RLS and potential comorbidities. Secondary causes of RLS and the characteristics of pediatric RLS are also discussed. Finally, management strategies for RLS are summarized.

Methods:

The review began with a comprehensive PubMed search for ‘restless legs syndrome/Willis-Ekbom disease’ in combination with the following: anxiety, arthritis, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, cardiac, cardiovascular disease, comorbidities, depression, end-stage renal disease, erectile dysfunction, fibromyalgia, insomnia, kidney disease, liver disease, migraine, mood disorder, multiple sclerosis, narcolepsy, neuropathy, obesity, pain, Parkinson’s disease, polyneuropathy, pregnancy, psychiatric disorder, sleep disorder, somatoform pain disorder, and uremia. Additional papers were identified by reviewing the reference lists of retrieved publications.

Results and Conclusions:

Although clinical diagnosis of RLS can be straightforward, diagnostic challenges may arise when patients present with comorbid conditions. Comorbidities of RLS include insomnia, depressive and anxiety disorders, and pain disorders. Differential diagnosis is particularly important, as some of the medications used to treat insomnia and depression may exacerbate RLS symptoms. Appropriate diagnosis and management of RLS symptoms may benefit patient well-being and, in some cases, may lessen comorbid disease burden. Therefore, it is important that physicians are aware of the presence of RLS when treating patients with conditions that commonly co-occur with the disorder.

Introduction

Restless legs syndrome (RLS), also known as Willis–Ekbom disease, is a chronic neurosensorimotor disorder, characterized by an urge to move the legs which is often accompanied by uncomfortable or unpleasant sensations. These symptoms can result in considerable discomfort and distress, and are recognized as having a significant health-related impact in patients with moderate-to-severe diseaseCitation1. Epidemiological studies have suggested that the prevalence of RLS in the general population may range from 5% to 15%Citation1. As many as one in 25 people may suffer from RLS symptoms that cause some degree of distress, and one in 100 may experience symptoms which seriously impact quality of lifeCitation1. In addition, patients with RLS may have an increased risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and strokeCitation2. The clinical importance of RLS is further underlined by the results of a large-scale prospective cohort study. Among 18,425 US men followed for 8 years, RLS was associated with a 39% increased risk of mortality (age-adjusted hazard ratio [HR]: 1.39, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.19–1.62; P < 0.0001)Citation3.

Although the pathophysiology of RLS is not fully understood, evidence exists for both iron/transferrin and dopaminergic abnormalities being factors in its etiology. As iron is a major cofactor in dopaminergic neurotransmission, iron deficits may produce dopaminergic changes that exacerbate RLS symptomsCitation4. Among patients with idiopathic/primary RLS, there is evidence for genetic predispositionCitation5. Genome-wide association studies have identified six different genes (BTBD9, MEIS1, MAP2K5/LBXCOR1, PTPRD, TOX3) with allelic variants that convey RLS riskCitation5. A familial pattern is seen in over 50% of patients with idiopathic RLS, and onset of symptoms before the age of 45 years indicates an increased risk of the disorder occurring among first- and second-degree family membersCitation6.

Although RLS is relatively common in the general population, it often remains undiagnosedCitation7. A large cohort study involving 62 primary-care practices in six Western European countries found that 91% of patients with RLS had not been previously diagnosedCitation8. Physicians play a pivotal role in the diagnosis and initial management of RLS; therefore, it is important that there is awareness of RLS comorbidities when a patient presents with a condition for which there is a high probability that RLS may be comorbid. The intent of this narrative review is to discuss appropriate diagnosis, recognition of comorbid conditions, and management of RLS.

Methods

Relevant studies published before November 2013 were identified via a comprehensive PubMed search using ‘restless legs syndrome’ in combination with the following terms: anxiety, arthritis, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, cardiac, cardiovascular disease, comorbidities, depression, end-stage renal disease, erectile dysfunction, fibromyalgia, insomnia, kidney disease, liver disease, migraine, mood disorder, multiple sclerosis, narcolepsy, neuropathy, obesity, pain, Parkinson’s disease, polyneuropathy, pregnancy, psychiatric disorder, sleep disorder, somatoform pain disorder, and uremia. Additional papers were identified by reviewing reference lists of relevant publications. Case reports, studies that were not conducted in humans and non-English-language publications were excluded. A systematic approach to study selection was not implemented. Instead, data were extracted on the basis of their relevance to the topic.

Diagnosis and caveats to diagnosis of RLS

Diagnosis of idiopathic RLS is made by patient history as there are no physical characteristics or markers for the disorder. Patients may have difficulty describing their symptoms, variously complaining of ‘pain’, ‘creepy-crawlies’, ‘electric current’, ‘jittery’, ‘burning’, ‘throbbing’, and ‘tearing’ inside the muscles of the extremities, primarily deep in the legsCitation6. RLS symptoms predominantly occur in the lower limbs, although any area from the hips to the feet can be impacted. In more severe cases, the upper extremities (shoulder to wrists) may be affectedCitation9 and some instances of facial symptoms have been reportedCitation10.

A patient’s description of RLS symptoms may vary; however, the disorder can be confirmed or ruled out on the basis of essential criteria defined by the International RLS Study Group (IRLSSG) using the acronym URGED: (1) Urge to move the legs usually but not always accompanied by unpleasant/uncomfortable sensations, (2) Rest worsens symptoms, (3) Gyration or movement partially/totally relieve symptoms, (4) Evening/nighttime onset or worsening of symptomsCitation6. The IRLSSG added a fifth criterion in 2011: occurrence of features 1–4 is not solely accounted for as symptoms primary to another medical/behavioral conditionCitation11 leading to the ‘D’ of URGED, (5) Denial of another primary causation of the symptoms. The DSM-5 criteria for RLS are consistent with the five IRLSSG criteria, and include the following additional specifications: RLS symptoms occur at least three times per week and have persisted for at least 3 months; symptoms cause significant distress or impairment on social, occupational, educational, academic or behavioral functioning; and the disturbance cannot be explained by the effects of a drug or abuse of medicationCitation12. Supportive clinical features for RLS include a positive family history, positive response to dopaminergic therapy, and presence of periodic limb movements in sleep (PLMS)Citation6. These features do not occur in every patient, but are particularly useful in diagnosing complicated or uncertain casesCitation6. In addition, the potential presence of RLS should be considered in patients who complain of early insomnia and paresthesias or dysesthesias of the legsCitation13.

PLMS are repetitive involuntary limb movements that are found in several sleep disorders, including narcolepsy, sleep apnea and RLS, and may also be present in healthy individuals. As these movements occur in at least 80% of patients with RLSCitation6,Citation14, they are considered to be a sign of the disorder. PLMS are characterized by extensions of the big toe and flexion at the ankle, knee, and hip as in a retraction response. They typically occur every 20–40 seconds and last for 0.5–5.0 secondsCitation6. PLMS can be accompanied by nighttime awakenings or transient arousals resulting in significant sleep disruption, although they can also represent an epiphenomenon. The sleep of the bed partner may also be disturbed due to the patient trembling or kicking out whilst asleep. Whereas RLS can be diagnosed on the basis of clinical symptoms using the IRLSSG criteria, PLMS can only be diagnosed during a sleep study via polysomnography or actimetry.

Patients with RLS generally do not need to be referred for diagnostic purposes; however, in ambiguous cases, patients may be referred to a neurologist or sleep specialist for further investigationCitation13. A diagnostic test completed in research settings, the Suggested Immobilization Test (SIT), can be used to assess severity of leg restlessness and therapeutic response. During SIT, the patient is asked to lie or sit with their legs outstretched and attempt to remain still for 30–60 minutes, during which leg movements are monitored by an electromyogram. In 80% of cases, a SIT index score of over 40 involuntary leg movements per hour can be used to differentiate between patients with or without RLSCitation13. One important aspect of diagnosis is delineation between idiopathic and secondary RLS. In the majority of cases, early-onset RLS (before the age of 45 years) is idiopathicCitation15. Secondary RLS tends to start after the age of 45 years and is associated with more rapid progression than idiopathic RLSCitation15. The three major secondary causes of RLS (iron deficiency, pregnancy, and end-stage renal disease [ESRD]) all compromise CNS iron availabilityCitation4.

Two major challenges in the differential diagnosis of RLS may contribute to the high proportion of patients who remain undiagnosedCitation16. Firstly, RLS may be comorbid with other disorders. Physical examinations are generally normal in patients with idiopathic RLS, but can be used to detect comorbidities or secondary causesCitation6. Secondly, other disorders can mimic the IRLSSG criteria (). The inner urge to move the limbs is often the key to distinguishing between RLS and mimic conditions that cause discomfortCitation16. In addition, many RLS mimics do not have a circadian rhythmicity and are not relieved by movement. Patient history directs the process to determine potential mimics that can then be ruled out based on specific physical findings. Complications in diagnosis arise as mimics such as neuropathy, arthritis, venous stasis, and positional discomfort may coexist with RLS; this further underscores the importance of awareness among medical providers of conditions that are commonly comorbid with RLS.

Table 1. Confounds in the differential diagnosis of RLS.

Comorbidities

Insomnia

RLS has been identified as the fourth leading cause of insomniaCitation17 and sleep disturbance is often the primary reason for patients with RLS seeking medical attention. Approximately 50–85% of RLS patients experience troubling insomnia affecting sleep onset and maintenanceCitation7,Citation8,Citation14,Citation18–23. The impact of RLS on health appears to be closely related to the frequency and severity of sleep disturbances. A European primary-care study found that individuals whose RLS had a ‘high’ negative impact on health had a significantly greater frequency of sleep disturbances (58% ≥4 nights/week) compared with patients whose RLS had ‘moderate’ (47% ≥4 nights/week), or ‘little/no’ negative impact (35% ≥4 nights/week) (P < 0.001)Citation8. Several controlled studies have shown a significant association between RLS and insomniaCitation20–23, and polysomnographic studies have demonstrated that patients with RLS experience reduced sleep efficiency, increased arousals, and reduced total sleep timeCitation24–26. Data from the Sleep Heart Health Study (n = 535) showed participants with RLS (n = 71) had a higher prevalence of insomnia (22.7% vs. 5.7%, P = 0.009) and higher sleep latency (49.47 ± 62.23 min vs. 27.34 ± 32.2 min, P = 0.014) than those without the disorderCitation27. Collectively, these data highlight the high prevalence of insomnia comorbid with RLS. It is especially important to determine whether RLS is the underlying cause of insomnia as RLS symptoms are often exacerbated by over-the-counter sleep medications that contain antihistaminesCitation28. Patients with insomnia often use these agents to self-medicate. Furthermore, prescription of medications with no effect on the underlying disorder will often be inadequate in managing insomnia in patients with RLS.

Depressive and anxiety disorders

Population-/community-based studiesCitation22,Citation23,Citation29–40 and clinic-based studiesCitation18,Citation25,Citation41–45 have consistently demonstrated an increased prevalence or risk of depression and/or anxiety in patients with RLS, although in two studies an increased risk of depression was seen in men but not in womenCitation29,Citation31. It should be noted that the majority of these studies did not adjust for antidepressant use. A prospective study of 56,399 women with no history of depression or regular antidepressant use found that participants with physician-diagnosed RLS at baseline had a higher risk of developing clinical depression (multivariate-adjusted relative risk [RR] = 1.5 [95% CI: 1.1, 2.1]; P = 0.02) and clinically relevant depressive symptoms (1.53 [1.33, 1.76]; P < 0.0001) over 6 years of follow-up than women without RLSCitation46. Another prospective study showed an increased 12 month risk of anxiety and depressive disorders, particularly panic disorder (odds ratio [OR] = 4.7 [95% CI: 2.1–10.1]), generalized anxiety disorder (OR = 3.5 [95% CI: 1.7–7.1]), and major depression (OR = 2.6 [95% CI: 1.5–4.4]) among patients with RLS (n = 130), compared with a community sample of patients with somatic illness (n = 2265)Citation44. In the majority of cases, the onset of RLS occurred prior to that of the psychiatric disorder. Antidepressant use was not reported.

Diagnosis of mood disorders in patients with RLS is complicated by symptom overlap. Fatigue, sleep disturbance, diminished concentration, and psychomotor agitation are common to both RLS and depressive disordersCitation47,Citation48. Causality between RLS and depression is unclear and seems to be bidirectional and multidimensionalCitation48,Citation49. In two prospective cohort studies (Dortmund Health Study [DHS], n = 1122, median follow-up: 2.1 years; Study of Health in Pomerania [SHIP], n = 3300, median follow-up: 5 years), clinically relevant depressive symptoms were associated with new-onset RLS (DHS, adjusted OR = 1.94 [95% CI: 1.09–3.44]; SHIP, adjusted OR = 2.37 [1.65–3.40])Citation50. Conversely, RLS at baseline was a risk factor for clinically relevant depression in the SHIP study (OR = 1.82 [95% CI: 1.1–3.0])Citation50. In both studies, sensitivity analyses that excluded participants on antidepressants yielded similar results to those listed above. Sleep disruption and fatigue due to RLS may be causal factors for depression or depressive symptoms. Sleep deprivation, poor nutrition, and lack of exercise may increase the risk of developing RLSCitation48. In a cross-sectional study of patients with ESRD (n = 949 [55 patients had ‘probable’ RLS])Citation51, multivariate analyses indicated that the presence of RLS symptoms was independently associated with depression (OR = 3.96 [95% CI: 2.21–7.1]). This relationship remained significant after adjusting for insomnia (OR = 2.9 [95% CI: 1.55–5.43]), indicating that the association of RLS with depression cannot be fully explained by sleep impairment in ESRD. Consistent results were obtained when patients on antidepressants, antihistamines or dopaminergic treatment were excluded. It is possible that RLS severity may be influenced by the degree of renal failure; thereby indirectly influencing depression and sleep quality. An unknown pathophysiological factor, or factors, common to both disorders (such as an abnormality in dopaminergic transmission or a genetic association) could falsely suggest a causal association between RLS and depressionCitation48. The possibility also exists that epidemiological association may, at least partly, be a result of overlap in the symptoms of two disorders which are both prevalent in the population.

Treatment of comorbid depression in patients with RLS must be carefully considered as antidepressants have been reported to trigger or exacerbate RLS symptoms (). Patients receiving the serotonin–noradrenalin reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine, and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) citalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline have been shown to have an elevated PLMS index in comparison with controls and patients taking bupropionCitation52. In an observational study (n = 271), RLS was recorded as a side-effect of antidepressant administration in 9% of patients and typically occurred during the first few days of treatmentCitation53. Mirtazapine induced or exacerbated RLS in 28% of patients, and SSRIs (citalopram, escitalopram, sertraline, paroxetine, and fluoxetine) and SNRIs (duloxetine and venlafaxine) induced RLS in around 5% of patients. Other epidemiological studies have reported conflicting resultsCitation47. In a retrospective chart review of 200 patients presenting with insomnia, no association was seen between RLS and use of antidepressantsCitation54. Similarly, antidepressant use was not shown to be a major risk factor for developing RLS in an observational study of 243 patients with affective and anxiety disordersCitation55.

Table 2. Medications and substances that may exacerbate RLS symptoms.

As patients with RLS appear to have higher rates of disorders commonly treated with SSRIs and SNRIsCitation48, prescribers should be aware of the potential for treatment-related exacerbation of RLS symptoms. Antidepressants with probable lower rates of exacerbation of RLS include buproprion, desipramine, trazodone, and nefazodoneCitation48.

Cardiovascular disease

The potential mechanisms for an association between RLS and cardiovascular disease (CVD) have been extensively discussed in previous review articlesCitation56,Citation57. RLS may be associated with vascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes and obesity. In addition, PLMS, with or without central nervous system microarousals or awakenings, are associated with transient rises in pulse rate and blood pressureCitation58. This sympathetic hyperactivity associated with PLMS may be an underlying factor in the increased risk for hypertension and CVD among patients with RLSCitation57.

A systematic review by Innes et al. identified 14 cross-sectional studies published between 1995 and 2010 with data for RLS and CVDCitation2. Of these, 11 studies reported significant associations between RLS and CVD with ORs ranging from 1.4 (1.1–1.9) to 2.9 (1.2–7.2) following adjustment for confoundersCitation30,Citation33,Citation38,Citation59–66. One study did not show an association between RLS and CVDCitation67, and two studies reported positive but non-significantCitation68/marginally significant associationsCitation22. The results of two cross-sectional studies indicated that CV risk may be related to the frequency of RLS symptomsCitation33,Citation66, and one study reported stronger associations between RLS, CAD and CVD among participants with ‘severely’ bothersome RLS symptoms (RLS and CAD, OR: 2.12 [95% CI: 1.2–3.75]; RLS and CVD: 2.33 [1.37–3.97]) than among those with ‘moderate’ RLS bothersomeness (1.98 [1.17–3.37]; 1.88 [1.14–3.09])Citation66. More recently, Winter et al. investigated the associations between RLS, vascular risk factors and CVD in two large-scale cross-sectional studies: one in female health care professionals (n = 30,262)Citation69, and one in male physicians (n = 22,786)Citation70. Hypercholesterolemia, diabetes and BMI were each associated with RLS in womenCitation69, whereas diabetes was the only vascular risk factor associated with RLS in menCitation70. In the female cohort, no significant relationships were observed between RLS and prevalent CVD (major CVD, myocardial infarction, and stroke)Citation69; however, in the male cohort, prevalent stroke was associated with an increased risk of RLS (1.40 [1.05–1.86) and prevalent myocardial infarction was associated with a decreased risk of RLS (0.73 [0.55–0.97])Citation70. The authors suggest that RLS may be a marker for increased prevalence of vascular risk factors, rather than an independent risk factor for CV events.

The potential relationship between RLS and CVD has also been investigated in prospective studies. In a cohort of older men (aged 55–69 years; n = 1986) followed up for 10 years, RLS was associated with ischemic stroke (adjusted OR = 1.67 [95% CI: 1.07–2.06]; P = 0.024). Men with RLS also had a slightly increased risk for an ischemic heart disease event; however, this was not statistically significant (OR = 1.24 [95% CI: 0.89–1.74), P = 0.206)Citation71. Li et al. carried out a prospective study of RLS and coronary heart disease (CHD) among women in the Nurses’ Health Study (n = 70,977; mean follow-up: 5.6 years)Citation72. Women with a duration of RLS of ≥3 years had an elevated risk of developing CHD (multivariable-adjusted HR = 1.72 [95% CI: 1.09–2.73]; P = 0.03), non-fatal MI (1.8 [1.07–3.01]) and fatal CHD (1.49 [0.55–4.04]) in comparison to women without RLSCitation72. In contrast to these results, no associations between RLS and CVD were observed in a large-scale study involving two cohorts: 29,756 female health professionals (aged ≥45 years; mean follow-up 6 years), and 19,182 male physicians (aged ≥40 years, mean follow-up 7.3 years)Citation73. Following adjustment for vascular risk factors, RLS (diagnosed according to the IRLSSG) was not associated with an increased risk for major CVD, stroke, myocardial infarction, CVD death or coronary revascularizationCitation73.

To date, most prospective studies have investigated the relationship between baseline RLS and incident CVD. However, Szentkiralyi et al. evaluated whether CV risk factors and vascular diseases predict the development of RLS based on data from the Dortmund Health Study (DHS, n = 1312, median follow-up: 2.1 years) and the Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP, n = 4308, median follow-up: 5 years)Citation74. Obesity was a risk factor for incident RLS in the DHS study (OR = 2.06 [95% CI: 1.22–3.47]; P < 0.01), and diabetes (1.89 [1.18–3.03]; P < 0.01), hypertension (1.41 [1.02–1.94]; P = 0.04) and hypercholesterolemia (1.4 [1.02–1.92]; P = 0.04) were each associated with incident RLS in the SHIP study. A history of MI or stroke was not a predictor of RLS. When the analysis was reversed, the presence of RLS at baseline was not associated with an increased risk of developing a CV risk factor or vascular disease. However, the authors note that the short follow-up periods of the two studies may have been insufficient to detect RLS-related CV risk.

Although most of the relevant studies have supported an association between RLS and CVD, some have had conflicting results. Further investigation is needed in order to fully elucidate the relationship between RLS and CVD.

Pain

Sleep disturbances may have a role in increasing and prolonging pain and fatigueCitation75. Many patients with RLS describe their symptoms as painful; this may be due, at least in part, to dopaminergic dysfunction as dopaminergic pathways may be involved in pain modulation and analgesiaCitation76.

Polyneuropathy

The paresthesias and dysesthesias associated with polyneuropathy are very similar to RLS symptoms and may result in misdiagnosis of RLSCitation77. Differentiating features include a more frequent distal extremity ‘burning’ complaint in polyneuropathy and/or the circadian intensification of RLS later in the day, normally higher in the calf or thigh. Polyneuropathy may be comorbid with RLS, and patients with both conditions can often distinguish between neuropathic and RLS discomfort.

Studies investigating the prevalence of RLS in polyneuropathy have varied considerably in terms of their design and the subtypes of polyneuropathy present within the patient populationCitation78–81. In a prospective study that used the IRLSSG diagnostic criteria, the prevalence of RLS among 28 patients with chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy was 39%, in comparison to 7% among 28 age- and gender-matched controls (P < 0.01)Citation80. In contrast, a case–control study found no difference in the prevalence of confirmed RLS (determined by a movement disorder specialist) between 245 patients with peripheral neuropathy and 245 age- and gender-matched controls (12% vs. 8%, P = 0.14); however, an increased prevalence of RLS was found among patients with hereditary neuropathy (P = 0.016)Citation79. In another study, the prevalence of RLS (according to the IRLSSG criteria) among 97 patients with polyneuropathy (30%) exceeded the estimated prevalence in the general population (7–10%), and was significantly greater than in other neurologic patients. Small-fiber sensory neuropathy was significantly more common among patients with RLS, suggesting that abnormal sensory inputs related to polyneuropathy may play a roleCitation78. Studies of RLS among diabetic neuropathy patients have shown a prevalence ranging from 9% to 33%Citation82,Citation83. Among a cohort of 99 patients with diabetic neuropathy, small-fiber neuropathy and symptoms of ‘burning feet’ were more common among the 33 patients with RLSCitation83. The frequent occurrence of RLS in association with thermal dysesthesias may be due to the involvement of small sensory fibers; abnormal sensory inputs from small fibers may trigger RLSCitation83.

Polydefkis et al. used skin biopsies to investigate the prevalence of large-fiber neuropathy and small sensory fiber loss (SSFL) in 22 patients with RLSCitation84. Neuropathy was identified in 8 patients (36%): 3 had pure large-fiber neuropathy, 2 had mixed large-fiber neuropathy and SSFL, and 3 had pure SSFL. Patients with SSFL had a later age of RLS onset (P < 0.009), tended to have no family history of RLS (P < 0.078), and were more likely to report painful symptoms (P < 0.001) compared to patients without SSFL. These authors suggest that a distinct subform of RLS may be triggered by the painful dysesthesias associated with SSFL.

The relationship between neuropathic pain and RLS (diagnosed according to the IRLSSG criteria) was specifically investigated in two studiesCitation85,Citation86. Firstly, a retrospective study reported a significantly higher frequency of RLS among patients with painful or dysesthetic polyneuropathy (n = 102) compared with patients with non-painful neuropathy (n = 178) (40% vs. 16%, P < 0.001). RLS was significantly associated with decreased small fiber input. The second study prospectively evaluated 58 patients with distal symmetric polyneuropathy (DSP) and symptoms of neuropathic pain or dysesthesiaCitation86. The prevalence of RLS among patients with DSP (36.2%) was higher than among age- and gender-matched healthy controls (3.6%; P < 0.0001). No significant differences were seen between DSP patients with and without RLS in terms of the cause, pattern (small fiber neuropathy/mixed small–large fiber neuropathy) and sensory profile of painful neuropathyCitation86.

Somatoform pain disorder

Patients with sleep disorders have an increased risk of developing somatoform symptomsCitation75,Citation87. An RLS prevalence of 42% was reported among 100 patients with somatoform pain disorder attending an outpatient clinicCitation75. Those with somatoform pain disorder and RLS experienced longer periods of pain and were more likely to experience continuous pain than those without RLS. Pain duration and pain parameters (maximal, medium, and minimal pain) increased with RLS severity. Several possible connections between RLS and somatoform pain have been described in the literatureCitation75. Disturbance of the monoaminergic system due to glucocorticoid induced monoamine depletion occurs as a result of chronic pain. Monoaminergic dysfunction of the dopamine system may play a role in the pathophysiology of RLS, as dopamine is required for the synthesis of noradrenalineCitation75. Pathophysiologic mechanisms link sleep disturbances, which are common among RLS patients, to pain. The use of non-opioid analgesics in conjunction with antidepressants is common among patients with somatoform pain disorder and may increase the risk of developing RLS ()Citation55,Citation75.

Rheumatoid arthritis

A high prevalence of RLS has been observed among patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA)Citation88–90. In a questionnaire survey, 28% (41/148) of respondents with RA and 24% (11/45) of respondents with osteoarthritis met all four IRLSSG diagnostic criteria for RLSCitation90. Although 52 (27%) respondents met all four IRLSSG criteria, only 5 (3%) had a previous RLS diagnosis. This suggests that RLS symptoms may be misinterpreted as symptoms of arthritis. Interestingly, 91% (69/76) of patients with RLS symptoms (patients meeting ≥1 of the IRLSSG criteria) felt that they could distinguish between RLS and arthritic symptoms, yet only 13 (17%) had sought medical attention for RLS.

Fibromyalgia

Fibromyalgia and RLS are both more prevalent among women than men, share in the complaint of sensory abnormality, and are associated with PLMS, fatigue, and insomniaCitation91,Citation92. Fibromyalgia may be misdiagnosed as RLS or vice versaCitation92. Studies of patients with fibromyalgia have shown a prevalence of RLS of 20–66%; however, in many of these studies the criteria for diagnosing RLS and/or fibromyalgia were poorly definedCitation92. Fibromyalgia and RLS may share a similar dopaminergic pathophysiologyCitation91,Citation92, and dopaminergic treatment has been shown to be beneficial in improving fibromyalgia symptomsCitation93. Furthermore, the paresthesias associated with fibromyalgia may share a similar pathogenetic mechanism to those associated with RLSCitation94. Antidepressants are commonly prescribed to treat patients with fibromyalgia; as previously discussed, the use of these medications may exacerbate RLS symptomsCitation92.

Secondary RLS

Iron deficiency

As previously mentioned, iron/transferrin abnormalities are implicated in the pathophysiology of RLS, and iron deficiency is widely recognized as a major secondary cause of the disorderCitation4. In a prospective study of patients with RLS attending a sleep disorders clinic (n = 302), 31% were found to have low serum ferritin levels (<50 µg/l)Citation95. High incidences of secondary RLS have been reported among populations at increased risk for iron insufficiency, for example pregnant women and patients with ESRD (as discussed later in this article). A hospital-based study in patients with iron-deficiency anemia reported a prevalence of RLS of 41%; however, these data were limited by small sample sizes and the absence of standardized assessment criteriaCitation96. A more stringent studyCitation97 included 251 patients with both anemia (Hgb < 14 for males and <12 for females) and iron deficiency (serum ferritin <20 µg/l or transferrin saturation <19%) attending a community-based hematology practice. Clinically significant RLS (diagnosed via a validated questionnaireCitation98) was present in 23.9% of anemic patientsCitation97, considerably higher than the prevalence of 2.7% reported within the general populationCitation19. A high prevalence of RLS has also been reported among blood donorsCitation99–101 who may have donation-induced iron depletionCitation102. However, several studies have failed to show an association between RLS, donation frequencyCitation99,Citation100,Citation103 and donor iron statusCitation99,Citation104.

Pregnancy

Although RLS is the most common movement disorder in pregnancy, it is poorly recognized by obstetriciansCitation105. Data from epidemiological studies indicate that RLS affects 10–34% of pregnant womenCitation105–116. Two prospective studies have examined RLS in pregnancy using the IRLSSG criteria. The prevalence of RLS among 500 pregnant women completing a mailed questionnaire was 17% in the first trimester, 27.1% in the second trimester, and 29.6% in the third trimesterCitation115. In the second study, 501 pregnant women were assessed for RLS by their attending physician and diagnosis was confirmed by an experienced neurologist. The reported prevalence of RLS was 12%Citation111. Among the women with RLS, 51% experienced RLS symptoms 5–7 times per week.

Factors associated with RLS in pregnancy include anemia (iron and folate deficiency), a history of childhood growing pains, and a family history of RLS and growing painsCitation105. Estrogen has also been implicated in pregnancy-related RLSCitation117. This is supported by data from a community-based cohort study (n = 535) that showed increased odds of developing RLS among estrogen users (OR = 2.5 [95% CI: 1.17–5.10]; P = 0.017)Citation27. Patients with pre-existing RLS tend to experience worsening of symptoms during the third trimester, and women with new-onset RLS tend to experience transient symptoms which appear during the third trimester and normally end within days after deliveryCitation113. Iron and folate supplementation may improve RLS symptoms in women with low serum ferritin levels; if symptoms are severe, treatment with opiates, gabapentin, or benzodiazepines may be considered as these drugs have an extensive safety record in pregnancyCitation118.

End-stage renal disease

Most studies examining the association between RLS and kidney disease have focused on dialysis-dependent patients with ESRD. A wide variability in rates of RLS (7–83%) has been observed among patients undergoing dialysisCitation119. This is likely to be due to differences in patient numbers, dialytic strategies, and criteria used to diagnose RLSCitation119. Four large-scale studies used the IRLSSG criteria and found a prevalence of RLS of 12–29%Citation119–122. In one study, few patients reported symptoms prior to dialysis and/or had a family history of the disorder, suggesting that hemodialysis may be associated with a distinct secondary form of RLSCitation120. Presence of RLS was associated with anemiaCitation121, high serum phosphate levelsCitation121, lower hemoglobin levelsCitation120, insomniaCitation119, anxietyCitation119,Citation121, depressionCitation119,Citation120, emotion-orientated coping with stressCitation121, obstructive sleep apneaCitation120, poor sleep qualityCitation120, and excessive daytime sleepinessCitation120. As reported earlier, the significant association between RLS and depression has been shown to be partly independent of insomnia in patients with ESRDCitation51.

Few studies have evaluated RLS in patients with non-dialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease (CKD). A case–control study found that non-dialyzed patients with chronic renal function (n = 138) had an almost five-fold increased risk of RLS occurrence than controls with normal renal function (n = 151) (OR = 4.9 [95% CI: 1.6–14.7]; P = 0.004)Citation123. Another study investigated the prevalence of RLS among 500 nephrology patients with varying degrees of kidney function. A similar RLS prevalence was observed among patients with ESRD on dialysis (26%), patients with non-dialysis dependant CKD (estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] < 60: 26%), and patients with normal renal function (eGFR ≥ 60: 18.9%) (P = 0.27)Citation124. Patients were recruited from nephrology clinics; therefore, patients included in the ‘normal’ group (eGFR ≥ 60) likely had some form of renal abnormality. In this study, RLS was not correlated with the severity of kidney disease. In contrast, two studies of non-dialyzed patients have reported an association between RLS and worsening severity of CKDCitation125,Citation126. In a Japanese study, a higher prevalence of RLS was observed among 514 patients with CKD than among 535 matched controls (3.5% vs. 1.5%, P = 0.029), and RLS prevalence increased with increasing CKD stage (stage 1 [eGFR: > 90]: 0%; stage 2 [60–89]: 1%; stage 3 [30–59]: 4.2%, stage 4 [15–29]: 3.2%; stage 5 [<15]: 7.4%) (χ2 = 8.08, P = 0.09)Citation125. Renal failure (CKD stage >3) was present in 94% of CKD patients with RLS, compared with 70% of CKD patients without RLS (P = 0.016)Citation125. Similarly, a study of 301 hospital patients (aged ≥50 years) showed an increasing prevalence of RLS with worsening renal function (no significant CKD: 15.5%; stage 3: 20.4%; stage 4: 35.3%; stage 5: 28.6% (χ2 for trend = 5.3, P = 0.04)Citation126. None of the patients with CKD were on dialysis. Patients with stage 4 CKD had a three-fold higher risk of RLS than those without CKD (adjusted OR = 3.08 [1.10–10.28]; P = 0.05). Together, these studies indicate that RLS is a common comorbidity among non-dialyzed patients with CKD.

Uremic RLS may be associated with more rapid disease progression, greater subjective disease severity, and a higher severity of sleep disturbance compared with idiopathic RLSCitation127. In addition, patients with uremic RLS may have a poorer response to dopaminergic treatment than patients with idiopathic RLSCitation127. Intravenous iron administration has been associated with a reduction in RLS symptoms in patients with ESRDCitation128. Oral iron administration may be less suitable for patients with chronic renal disease, as their intestinal iron absorption is often impaired due to disorders of hepcidin/ferroportin regulation and inflammationCitation129. The presence of RLS among dialyzed uremic patients does not seem to be associated with cause of ESRDCitation119, transplant historyCitation119, or type of dialysisCitation119,Citation130,Citation131. Two studies have shown a relationship between RLS and time on dialysisCitation119,Citation132, and one study has shown an increased risk of insomnia among patients undergoing dialysis treatment for over 12 monthsCitation133; however, other studies have had conflicting resultsCitation130,Citation131. RLS symptoms have been shown to improve in patients with ESRD following kidney transplantationCitation134.

In patients on dialysis, RLS has been shown to be associated with lower quality of lifeCitation135,Citation136 and severe RLS symptoms have been associated with increased mortalityCitation136,Citation137. A study of 804 kidney transplant recipients reported significantly greater mortality after 4 years among patients who had RLS at baseline (univariate HR for the presence of RLS: 2.53 [95% CI: 1.31–4.87]) compared with those without the disorder. RLS was a significant predictor of mortality (HR = 2.02 [95% CI: 1.03–3.95])Citation138. RLS is also associated with poor sleep, insomnia, and impaired quality of life among patients receiving a kidney transplantCitation139. Sleep disturbances associated with RLS may contribute to the development of cardiovascular complications and infections, which are significant causes of mortality in patients with ESRDCitation119. In a prospective, observational study of 100 patients on dialysis, a higher severity of RLS (intermittent vs. continuous) was associated with a higher risk of new cardiovascular events and higher short-term mortalityCitation140. Similarly, PLMS are an independent predictor of higher cardiovascular and cerebrovascular risk in patients with chronic kidney diseaseCitation141.

Other comorbidities

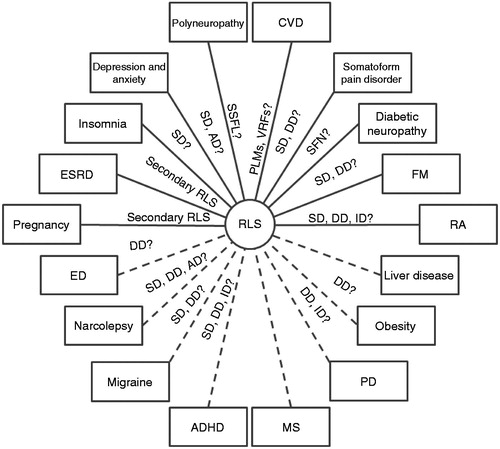

RLS has been linked in the literature with a number of other medical conditions, including narcolepsy, obesity, migraine, and Parkinson’s disease. Since the evidence for these associations comes mainly from epidemiologic studies (), more research is needed. Dopaminergic dysfunction has been implicated in many potential comorbidities. For example, modification of dopaminergic pathways has been reported in narcolepsyCitation188, obesity has been shown to decrease D2 receptor availability in the brainCitation189 migraine has been associated with dysfunctions in dopamine and iron metabolismCitation156, and the involvement of dopamine deficiency in the pathophysiology of Parkinson’s disease is well establishedCitation190. Determining the prevalence of RLS among patients with PD is particularly challenging due to the difficulty in discriminating between PD-related akathisia and the sensory symptoms of RLS. As dopaminergic treatment for PD is efficacious in ameliorating RLS symptoms, the incidence of RLS among patients with PD may be underestimatedCitation191. Conversely, long-term dopaminergic therapy may contribute to the emergence of RLS in patients with PD due to dopaminergic-related augmentation (exacerbation) of previously subclinical symptomsCitation191.

Table 3. Comorbidities which may be associated with RLS based on epidemiological data.

Pediatric RLS

Approximately 40% of adults with RLS first experience symptoms as children or adolescentsCitation14. Symptoms may remit and then reappear when the patient is 30–40 years of age. A large epidemiological study (10,523 families) found a prevalence of RLS of 1.9% among 8–11-year-olds and 2.0% among 12–17-year-oldsCitation143. Clinical diagnosis is complicated as younger children in particular may struggle to describe subjective symptoms. Children with RLS may present with different symptoms to adults, and may exhibit mood and behavioral problems as a result of disrupted sleep ()Citation192.

Table 4. Presenting symptoms of RLS in children.

The IRLSSG has developed specific criteria for the diagnosis of pediatric RLSCitation6. These criteria are stricter than those required for a diagnosis of adult RLS in order to prevent over-diagnosis and to account for high levels of motor activity exhibited by childrenCitation6. For a diagnosis of ‘definite’ RLS, children (aged 2–12 years) must fulfill all of the adult diagnostic criteria and describe symptoms consistent with leg discomfort. If a child is unable to describe their symptoms, they must fulfill two of the following three supportive criteria: (1) sleep disturbance atypical for their age; (2) biological parent or sibling with definite RLS; (3) polysomnographically documented periodic limb movement (PLM) index of at least 5 PLM/hour of sleep. Criteria for ‘probable’ and ‘possible’ RLS have also been developed for use in children up to the age of 18 yearsCitation6.

An epidemiological survey performed in the United States and United Kingdom found that only 11% (9/81) of children (aged 8–11 years) and 11% (14/125) of adolescents (aged 12–17 years) who fulfilled IRLSSG criteria for definite RLS had previously been diagnosed with the disorderCitation143. Many confounds in the differential diagnosis of RLS () occur in children as well as in adults. In addition, childhood onset RLS may be misdiagnosed as growing painsCitation193. A high prevalence of comorbid conditions has been observed in pediatric RLS patients. In a retrospective assessment of 18 children and adolescents with RLS, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety, depression, parasomnia, and oppositional defiant disorder were each found in >20% of patientsCitation194. Up to 25% of patients with RLS may suffer from ADHDCitation142 (), and the two disorders share similar features. For example, sleep deprivation due to RLS may result in behavior consistent with ADHD, and iron deficiency and dopamine dysfunction have been implicated in the pathophysiology of both conditionsCitation192.

As previously discussed, RLS may occur secondary to CKD. Studies of pediatric patients with CKD have reported an RLS prevalence ranging from 10% to 35%Citation195–199. This range includes both dialysis-dependent and non-dialysis-dependent patients. The wide variation in reported RLS prevalence is likely due to differences in the severity of CKD within the patient populations, the study methodologies and the criteria that were used to diagnose RLS. The most rigorous study was a controlled cross-sectional investigation of CKD patients aged 8–18 years who were recruited from outpatient clinics and a hemodialysis unit. The NIH criteria were applied for diagnosis of RLS and patients with mimic conditions were systematically excludedCitation199. An RLS prevalence of 15.3% was observed among children with CKD, in comparison to 5.9% among healthy controls (P = 0.04)Citation199. Of the 19 children with CKD and RLS, only five had told a healthcare provider about their RLS symptoms; one child had received a diagnosis of RLS, one had been diagnosed with growing pains, and one with muscle crampsCitation199. These results illustrate the importance of screening and differential diagnosis of RLS in children who may be at increased risk of the disorder due to the presence of potential comorbidities.

Management of RLS symptoms

Once correctly diagnosed, management strategies for RLS are defined by the severity and frequency of symptoms. In mild cases, symptoms may be improved by lifestyle changes and self-help measuresCitation200. Education, improvements in sleep hygiene, cognitive behavioral therapy and distracting techniques such as reading, stretching, massage, and exercise may help patients to cope with their symptomsCitation200,Citation201. Improvements in RLS-related quality of life, mental health status, and subjective ratings of RLS symptom severity have been observed in patients receiving cognitive behavioral therapy to improve their coping strategiesCitation201. Medications such as SNRIs, SSRIs, and dopamine blockers should be reviewed by the patient’s medical team and avoided if possible, as should caffeine and excessive alcohol in the afternoon and evening ()Citation200. Possible secondary causes of RLS should be identified and treated whenever possible.

Treatment with oral iron reduces RLS symptoms in many, but not all, patients with low peripheral iron storesCitation4. Patients with low serum ferritin levels (10–50 ng/mL) should be given oral iron supplementation. The standard supplement is 325 mg of ferrous sulfate, taken orally three times per day in combination with vitamin C to aid absorptionCitation202. Unfortunately, gastrointestinal symptoms, particularly constipation, often limit the successful use of iron supplements. Formulations of iron that attempt to reduce constipation may be better tolerated by patients. Intravenous iron has been proposed as a method to reduce the gastrointestinal side effects, but evidence for its efficacy is limited. Low-to-moderate responder rates have been reportedCitation203–205, with few responders experiencing a sustained therapeutic effect past 6 monthsCitation204. Blood transfusions can be considered for severely anemic patientsCitation200.

Patients with moderate-to-severe symptoms of RLS show disturbance of daily activities, quality of life and/or sleep, and benefit from pharmacologic therapyCitation200. A number of effective treatment options are available (). Three non-ergot dopamine agonists, pramipexole, ropinirole, and rotigotine transdermal system, are approved for the treatment of moderate-to-severe idiopathic RLS by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency. In addition, the α-2-δ calcium-channel ligand gabapentin enacarbil is approved for the treatment of moderate-to-severe RLS in the United States and JapanCitation206,Citation210.

Table 5. Pharmacological therapy for restless legs syndromeCitation202,Citation206–209.

Treatment guidelines recommend non-ergot dopamine receptor agonists for initial treatment of patients with very severe RLS symptoms, excessive weight, comorbid depression, increased risk of falls or cognitive impairmentCitation202,Citation207. Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the efficacy of pramipexole, ropinirole and rotigotine versus placebo in improving RLS symptom severity, as assessed by the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group rating scaleCitation206–208. Based on the available evidence, all three agents are considered ‘effective’ in treating RLS for up to 6 monthsCitation207. Longer-term studies are limited; ropinirole and pramipexole have been established as ‘probably’ effective for up to 1 year, and rotigotine as ‘probably effective’ for up to 5 yearsCitation207. No head-to-head comparisons have been performed. Pramipexole and ropinirole are administered orally, and should be taken 1–3 h before bedtime, or upon symptom onset. Extended release formulations are available but have not been evaluated in RLS. Rotigotine is administered via a transdermal patch which is applied once daily, and worn for 24 hours before being replaced. This 24 hour coverage may be particularly beneficial for patients who experience RLS symptoms during the dayCitation202. Doses of all three medications should be kept low in order to minimize potential side effects. Dopaminergic adverse events include nausea, fatigue, headache, dizziness, orthostatic hypotension and daytime somnolenceCitation206–208. Hypersomnia and sleep attacks may occur at higher doses. Skin reactions related to rotigotine patch application were reported in 58% of patients with RLS participating in a 5 year open-label studyCitation211. Impulse control disorders (ICDs) such as compulsive shopping, pathologic gambling and punding may develop in 6–17% of patients taking dopamine receptor agonistsCitation207.

Augmentation (treatment-induced exacerbation of RLS symptoms) is the main complication of long-term dopaminergic therapy and was first reported with the dopamine precursor levodopa, the first dopaminergic therapy to be used for RLS. Characteristic features of augmentation include an increase in RLS symptom intensity, the onset of symptoms earlier in the day, a shorter time to symptom onset during periods of rest, spread of symptoms to previously unaffected body parts, and a shorter period of relief following the administration of medicationCitation212. Affected patients experience a worsening of RLS symptoms beyond baseline levels and a paradoxical response to treatment; symptoms worsen following an increase in dose and improve following a dose reductionCitation212. In order to reduce the risk of augmentation, dopaminergic therapy should be maintained at the lowest possible dose. As augmentation is associated with iron deficiencyCitation213, serum ferritin levels should be monitored and iron treatment initiated if appropriateCitation212. Augmentation appears to be less common with the dopamine agonists than with levodopa, although incidences cannot be directly compared due to a lack of comparative studies. Reported 6-month incidences were 60% with levodopaCitation214, 9.2% with pramipexoleCitation215, 3.5% with ropiniroleCitation216 and 1.5% with rotigotineCitation217. The short-term efficacy (up to 6 weeks) of levodopa has been demonstrated in clinical trialsCitation206 and occasional use may be beneficial for patients with intermittent RLS symptoms (). However, this medication is not recommended for chronic therapy due to the high risk of developing augmentationCitation202,Citation206–208.

The α-2-δ ligands are recommended as initial treatment for patients whose sleep disturbance outweighs their sensory symptoms, comorbid insomnia, anxiety, or pain, or for patients with a history of anxiety or ICDs ()Citation202,Citation207. Gabapentin enacarbil is the only non-dopaminergic therapy approved by the FDA for the treatment of moderate-to-severe RLS. Its efficacy in improving RLS symptoms, as assessed by the IRLS, has been demonstrated in placebo-controlled trials of up to 52 weeks in durationCitation206. Improvements in sleep architecture and mood have also been reportedCitation206. Long-term treatment guidelines consider gabapentin enacarbil ‘probably effective’ for 1 year of treatmentCitation207. Two other α-2-δ ligands, gabapentin and pregabalin, may be used off label (). Low-level evidence supports their use in RLSCitation206. Common side effects of all three α-2-δ ligands include somnolence and dizzinessCitation206,Citation207. There are no reports of augmentation with these medications. Weight gain and suicidal behavior and ideation may occur with pregabalinCitation206.

High potency opioids can be considered for patients whose RLS symptoms do not respond to therapy with dopamine agonists or with α-2-δ ligands ()Citation202. Oxycodone, hydrocodone or methadone may be used as monotherapy, or in combination with a dopamine agonist or anticonvulsant. Clinical evidence for the effectiveness of these medications in RLS is limitedCitation206–208. Doses should be kept low (∼5–20 mg) due to the potential for addiction and tolerance. Patients with intermittent RLS symptoms may benefit from occasional use of codeine, tramadol or oxycodone. These medications may be taken at bed-time or during the day if breakthrough RLS symptoms occur. Side effects of opioid therapy include constipation, nausea, dizziness, sedation and respiratory depression. Patients should be monitored for the development or worsening of sleep apnea, as opioids are known to cause respiratory depression. Augmentation has been reported with tramadolCitation218,Citation219.

Intermittent therapy with benzodiazepines may be considered for patients with RLS and comorbid insomnia, or patients for whom RLS-related sleep disturbances outweigh their sensory symptoms (). Zaleplon may be useful for inducing sleep, zolpidem may improve both sleep onset and maintenance, and temazepam and eszopiclone may be beneficial in reducing RLS-related awakenings as their half-lives are compatible with 8 hours of sleepCitation202. Evidence for the efficacy of these agents in RLS is lacking, but it is likely that they act by improving sleep rather than by reducing the sensory and motor symptoms of RLSCitation202.

No medications have been approved to date by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of RLS in children; however, medications which are accepted for usage in the pediatric population such as clonidine, clonazepam, and gabapentin have been prescribed off labelCitation220. Dopaminergic agents are also used, although their effects in children have not been extensively studiedCitation220.

Conclusions

RLS is a common sensorimotor disorder which can cause considerable morbidity and have a significant impact on quality of life. RLS is a clinical diagnosis based on an interview; however, it is frequently unrecognized in medical practice largely due to comorbidities that can mimic its symptoms. Although other conditions share similar characteristics, the differential diagnosis of RLS is generally possible via careful consideration of the IRLSSG criteria and supportive features. RLS can be comorbid with a variety of other conditions and the relationship between RLS and these conditions is not fully elucidated (). Identification of patients with RLS is particularly important, as many medications which are used to treat common comorbidities, such as antihistamines and antidepressants, may exacerbate RLS symptoms (). Despite potential difficulties in differential diagnosis, correct identification and management are crucial in order to prevent the potential clinical consequences of RLS. A number of treatments are available that allow RLS to be effectively managed.

Figure 1. Possible associations between RLS and comorbidities. Dotted lines indicate comorbidities for which the evidence for the association comes from epidemiologic studies. AD = use of antidepressants; ADHD = attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; CVD = cardiovascular disease; DD = dopaminergic dysfunction; ED = erectile dysfunction; ESRD = end-stage renal disease; FM = fibromyalgia; ID = iron deficiency; MS = multiple sclerosis; PD = Parkinson’s disease; PLMs = periodic limb movements; RA = rheumatoid arthritis; RLS = restless legs syndrome; SD = sleep disruption; SFN = small fiber neuropathy; SSFL = small sensory fiber loss; VRFs = vascular risk factors.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Writing and editorial assistance was funded by UCB Pharma, Smyrna, GA, USA. The sponsor was given the opportunity to review the manuscript for scientific and medical accuracy.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

P.M.B. has disclosed that he has consulted for UCB, GlaxoSmithKline, and Xenoport and has been a research investigator for Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, and Sensory Medical. M.N. has disclosed that she has no significant relationships with or financial interests in any commercial companies related to this study or article.

CMRO peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from CMRO for their review work, but have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Hannah Carney PhD, Evidence Scientific Solutions, Horsham, UK, for writing and editorial assistance, which was funded by UCB Pharma, Smyrna, GA, USA.

References

- Earley CJ, Silber MH. Restless legs syndrome: understanding its consequences and the need for better treatment. Sleep Med 2010;11:807-15

- Innes KE, Selfe TK, Agarwal P. Restless legs syndrome and conditions associated with metabolic dysregulation, sympathoadrenal dysfunction, and cardiovascular disease risk: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev 2012;16:309-39

- Li Y, Wang W, Winkelman JW, et al. Prospective study of restless legs syndrome and mortality among men. Neurology 2013;81:52-9

- Allen RP, Earley CJ. The role of iron in restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord 2007;22(Suppl 18):S440-8

- Freeman AA, Rye DB. The molecular basis of restless legs syndrome. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2013;23:895-900

- Allen RP, Picchietti D, Hening WA, et al. Restless legs syndrome: diagnostic criteria, special considerations, and epidemiology. A report from the restless legs syndrome diagnosis and epidemiology workshop at the National Institutes of Health. Sleep Med 2003;4:101-19

- Hening W, Walters AS, Allen RP, et al. Impact, diagnosis and treatment of restless legs syndrome (RLS) in a primary care population: the REST (RLS epidemiology, symptoms, and treatment) primary care study. Sleep Med 2004;5:237-46

- Allen RP, Stillman P, Myers AJ. Physician-diagnosed restless legs syndrome in a large sample of primary medical care patients in western Europe: prevalence and characteristics. Sleep Med 2010;11:31-7

- Koo YS, Lee GT, Lee SY, et al. Topography of sensory symptoms in patients with drug-naïve restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med 2013;14:1369-74

- Buchfuhrer MJ. Restless legs syndrome (RLS) with expansion of symptoms to the face. Sleep Med 2008;9:188-90

- International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group. Revised IRLSSG Diagnostic Criteria for RLS. 2012. Available at: http://irlssg.org/diagnostic-criteria/ [Last accessed November 2013]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association, 2013:410-13

- Chaudhuri KR, Forbes A, Grosset D, et al. Diagnosing restless legs syndrome (RLS) in primary care. Curr Med Res Opin 2004;20:1785-95

- Montplaisir J, Boucher S, Poirier G, et al. Clinical, polysomnographic, and genetic characteristics of restless legs syndrome: a study of 133 patients diagnosed with new standard criteria. Mov Disord 1997;12:61-5

- Allen RP, Earley CJ. Defining the phenotype of the restless legs syndrome (RLS) using age-of-symptom-onset. Sleep Med 2000;1:11-19

- Benes H, Walters AS, Allen RP, et al. Definition of restless legs syndrome, how to diagnose it, and how to differentiate it from RLS mimics. Mov Disord 2007;22(Suppl 18):S401-8

- Coleman RM, Roffwarg HP, Kennedy SJ, et al. Sleep–wake disorders based on a polysomnographic diagnosis. A national cooperative study. JAMA 1982;247:997-1003

- Bassetti CL, Mauerhofer D, Gugger M, et al. Restless legs syndrome: a clinical study of 55 patients. Eur Neurol 2001;45:67-74

- Allen RP, Walters AS, Montplaisir J, et al. Restless legs syndrome prevalence and impact: REST general population study. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:1286-92

- Bjorvatn B, Leissner L, Ulfberg J, et al. Prevalence, severity and risk factors of restless legs syndrome in the general adult population in two Scandinavian countries. Sleep Med 2005;6:307-12

- Ulfberg J, Bjorvatn B, Leissner L, et al. Comorbidity in restless legs syndrome among a sample of Swedish adults. Sleep Med 2007;8:768-72

- Phillips B, Hening W, Britz P, Mannino D. Prevalence and correlates of restless legs syndrome: results from the 2005 National Sleep Foundation Poll. Chest 2006;129:76-80

- Broman JE, Mallon L, Hetta J. Restless legs syndrome and its relationship with insomnia symptoms and daytime distress: epidemiological survey in Sweden. Psychiatr Clin Neurosci 2008;62:472-5

- Hornyak M, Feige B, Voderholzer U, et al. Polysomnography findings in patients with restless legs syndrome and in healthy controls: a comparative observational study. Sleep 2007;30:861-5

- Saletu B, Anderer P, Saletu M, et al. EEG mapping, psychometric, and polysomnographic studies in restless legs syndrome (RLS) and periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD) patients as compared with normal controls. Sleep Med 2002;3(Suppl):S35-42

- Winkelman JW, Redline S, Baldwin CM, et al. Polysomnographic and health-related quality of life correlates of restless legs syndrome in the Sleep Heart Health Study. Sleep 2009;32:772-8

- Budhiraja P, Budhiraja R, Goodwin JL, et al. Incidence of restless legs syndrome and its correlates. J Clin Sleep Med 2012;8:119-24

- Chokroverty S. Long-term management issues in restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord 2011;26:1378-85

- Rothdach AJ, Trenkwalder C, Haberstock J, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of RLS in an elderly population: the MEMO study. Memory and Morbidity in Augsburg Elderly. Neurology 2000;54:1064-8

- Ulfberg J, Nyström B, Carter N, Edling C. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome among men aged 18 to 64 years: an association with somatic disease and neuropsychiatric symptoms. Mov Disord 2001;16:1159-63

- Sukegawa T, Itoga M, Seno H, et al. Sleep disturbances and depression in the elderly in Japan. Psychiatr Clin Neurosci 2003;57:265-70

- Sevim S, Dogu O, Kaleagasi H, et al. Correlation of anxiety and depression symptoms in patients with restless legs syndrome: a population based survey. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr 2004;75:226-30

- Winkelman JW, Finn L, Young T. Prevalence and correlates of restless legs syndrome symptoms in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort. Sleep Med 2006;7:545-52

- Lee HB, Hening WA, Allen RP, et al. Restless legs syndrome is associated with DSM-IV major depressive disorder and panic disorder in the community. J Neuropsychiatr Clin Neurosci 2008;20:101-5

- Cho SJ, Hong JP, Hahm BJ, et al. Restless legs syndrome in a community sample of Korean adults: prevalence, impact on quality of life, and association with DSM-IV psychiatric disorders. Sleep 2009;32:1069-76

- Kim J, Choi C, Shin K, et al. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome and associated factors in the Korean adult population: the Korean Health and Genome Study. Psychiatr Clin Neurosci 2005;59:350-3

- Kim WH, Kim BS, Kim SK, et al. Restless legs syndrome in older people: a community-based study on its prevalence and association with major depressive disorder in older Korean adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2012;27:565-72

- Wesstrom J, Nilsson S, Sundstrom-Poromaa I, Ulfberg J. Restless legs syndrome among women: prevalence, co-morbidity and possible relationship to menopause. Climacteric 2008;11:422-8

- Nomura T, Inoue Y, Kusumi M, et al. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome in a rural community in Japan. Mov Disord 2008;23:2363-9

- Kim KW, Yoon IY, Chung S, et al. Prevalence, comorbidities and risk factors of restless legs syndrome in the Korean elderly population – results from the Korean Longitudinal Study on Health and Aging. J Sleep Res 2010;19:87-92

- Mosko S, Zetin M, Glen S, et al. Self-reported depressive symptomatology, mood ratings, and treatment outcome in sleep disorders patients. J Clin Psychol 1989;45:51-60

- Banno K, Delaive K, Walld R, Kryger MH. Restless legs syndrome in 218 patients: associated disorders. Sleep Med 2000;1:221-9

- Vandeputte M, de Weerd A. Sleep disorders and depressive feelings: a global survey with the Beck depression scale. Sleep Med 2003;4:343-5

- Winkelmann J, Prager M, Lieb R, et al. ‘Anxietas tibiarum’. Depression and anxiety disorders in patients with restless legs syndrome. J Neurol 2005;252:67-71

- Aguera-Ortiz L, Perez MI, Osorio RS, et al. Prevalence and clinical correlates of restless legs syndrome among psychogeriatric patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2011;26:1252-9

- Li Y, Mirzaei F, O'Reilly EJ, et al. Prospective study of restless legs syndrome and risk of depression in women. Am J Epidemiol 2012;176:279-88

- Hornyak M. Depressive disorders in restless legs syndrome: epidemiology, pathophysiology and management. CNS Drugs 2010;24:89-98

- Picchietti D, Winkelman JW. Restless legs syndrome, periodic limb movements in sleep, and depression. Sleep 2005;28:891-8

- Gupta R, Lahan V, Goel D. A study examining depression in restless legs syndrome. Asian J Psychiatr 2013;6:308-12

- Szentkiralyi A, Volzke H, Hoffmann W, et al. The relationship between depressive symptoms and restless legs syndrome in two prospective cohort studies. Psychosom Med 2013;75:359-65

- Szentkiralyi A, Molnar MZ, Czira ME, et al. Association between restless legs syndrome and depression in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Psychosom Res 2009;67:173-80

- Yang C, White DP, Winkelman JW. Antidepressants and periodic leg movements of sleep. Biol Psychiatr 2005;58:510-14

- Rottach KG, Schaner BM, Kirch MH, et al. Restless legs syndrome as side effect of second generation antidepressants. J Psychiatr Res 2008;43:70-5

- Brown LK, Dedrick DL, Doggett JW, Guido PS. Antidepressant medication use and restless legs syndrome in patients presenting with insomnia. Sleep Med 2005;6:443-50

- Leutgeb U, Martus P. Regular intake of non-opioid analgesics is associated with an increased risk of restless legs syndrome in patients maintained on antidepressants. Eur J Med Res 2002;7:368-78

- Ferini-Strambi L, Walters AS, Sica D. The relationship among restless legs syndrome (Willis–Ekbom Disease), hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and cerebrovascular disease. J Neurol 2013 [Epub ahead of print]

- Walters AS, Rye DB. Review of the relationship of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movements in sleep to hypertension, heart disease, and stroke. Sleep 2009;32:589-97

- Siddiqui F, Strus J, Ming X, et al. Rise of blood pressure with periodic limb movements in sleep and wakefulness. Clin Neurophysiol 2007;118:1923-30

- Juuti AK, Laara E, Rajala U, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of restless legs in a 57-year-old urban population in northern Finland. Acta Neurol Scand 2010;122:63-9

- Berger K, Luedemann J, Trenkwalder C, et al. Sex and the risk of restless legs syndrome in the general population. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:196-202

- Moller C, Wetter TC, Koster J, Stiasny-Kolster K. Differential diagnosis of unpleasant sensations in the legs: prevalence of restless legs syndrome in a primary care population. Sleep Med 2010;11:161-6

- Mallon L, Broman JE, Hetta J. Restless legs symptoms with sleepiness in relation to mortality: 20-year follow-up study of a middle-aged Swedish population. Psychiatr Clin Neurosci 2008;62:457-63

- Ohayon MM, Roth T. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder in the general population. J Psychosom Res 2002;53:547-54

- Foley D, Ancoli-Israel S, Britz P, Walsh J. Sleep disturbances and chronic disease in older adults: results of the 2003 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America Survey. J Psychosom Res 2004;56:497-502

- Alattar M, Harrington JJ, Mitchell CM, Sloane P. Sleep problems in primary care: a North Carolina Family Practice Research Network (NC-FP-RN) study. J Am Board Fam Med 2007;20:365-74

- Winkelman JW, Shahar E, Sharief I, Gottlieb DJ. Association of restless legs syndrome and cardiovascular disease in the Sleep Heart Health Study. Neurology 2008;70:35-42

- Benediktsdottir B, Janson C, Lindberg E, et al. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome among adults in Iceland and Sweden: Lung function, comorbidity, ferritin, biomarkers and quality of life. Sleep Med 2010;11:1043-8

- Lee HB, Hening WA, Allen RP, et al. Race and restless legs syndrome symptoms in an adult community sample in east Baltimore. Sleep Med 2006;7:642-5

- Winter AC, Schürks M, Glynn RJ, et al. Vascular risk factors, cardiovascular disease, and restless legs syndrome in women. Am J Med 2013;126:220-7, 27 e1-2

- Winter AC, Berger K, Glynn RJ, et al. Vascular risk factors, cardiovascular disease, and restless legs syndrome in men. Am J Med 2013;126:228-35, 35 e1-2

- Elwood P, Hack M, Pickering J, et al. Sleep disturbance, stroke, and heart disease events: evidence from the Caerphilly cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health 2006;60:69-73

- Li Y, Walters AS, Chiuve SE, et al. Prospective study of restless legs syndrome and coronary heart disease among women. Circulation 2012;126:1689-94

- Winter AC, Schürks M, Glynn RJ, et al. Restless legs syndrome and risk of incident cardiovascular disease in women and men: prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000866

- Szentkiralyi A, Volzke H, Hoffmann W, et al. A time sequence analysis of the relationship between cardiovascular risk factors, vascular diseases and restless legs syndrome in the general population. J Sleep Res 2013;22:434-42

- Aigner M, Prause W, Freidl M, et al. High prevalence of restless legs syndrome in somatoform pain disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatr Clin Neurosci 2007;257:54-7

- Hornyak M, Sohr M, Busse M, 604 and 615 Study groups. Evaluation of painful sensory symptoms in restless legs syndrome: experience from two clinical trials. Sleep Med 2011;12:186-9

- Nineb A, Rosso C, Dumurgier J, et al. Restless legs syndrome is frequently overlooked in patients being evaluated for polyneuropathies. Eur J Neurol 2007;14:788-92

- Gemignani F, Brindani F, Negrotti A, et al. Restless legs syndrome and polyneuropathy. Mov Disord 2006;21:1254-7

- Hattan E, Chalk C, Postuma RB. Is there a higher risk of restless legs syndrome in peripheral neuropathy? Neurology 2009;72:955-60

- Rajabally YA, Shah RS. Restless legs syndrome in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. Muscle Nerve 2010;42:252-6

- Rutkove SB, Matheson JK, Logigian EL. Restless legs syndrome in patients with polyneuropathy. Muscle Nerve 1996;19:670-2

- O'Hare JA, Abuaisha F, Geoghegan M. Prevalence and forms of neuropathic morbidity in 800 diabetics. Ir J Med Sci 1994;163:132-5

- Gemignani F, Brindani F, Vitetta F, et al. Restless legs syndrome in diabetic neuropathy: a frequent manifestation of small fiber neuropathy. J Peripheral Nervous System 2007;12:50-3

- Polydefkis M, Allen RP, Hauer P, et al. Subclinical sensory neuropathy in late-onset restless legs syndrome. Neurology 2000;55:1115-21

- Gemignani F, Brindani F, Vitetta F, Marbini A. Restless legs syndrome and painful neuropathy – retrospective study. A role for nociceptive deafferentation? Pain Med 2009;10:1481-6

- Gemignani F, Vitetta F, Brindani F, et al. Painful polyneuropathy associated with restless legs syndrome. Clinical features and sensory profile. Sleep Med 2013;14:79-84

- Saletu B, Brandstätter N, Frey R, et al. [Clinical aspects of sleep disorders – experiences with 817 patients of an ambulatory sleep clinic; comment]. Wien Klin Wochenschr 1997;109:390-9

- Reynolds G, Blake DR, Pall HS, Williams A. Restless leg syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis. Br Med J (Clinical Research Ed) 1986;292:659-60

- Salih AM, Gray RE, Mills KR, Webley M. A clinical, serological and neurophysiological study of restless legs syndrome in rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol 1994;33:60-3

- Taylor-Gjevre RM, Gjevre JA, Skomro R, Nair B. Restless legs syndrome in a rheumatoid arthritis patient cohort. J Clin Rheumatol 2009;15:12-15

- Stehlik R, Arvidsson L, Ulfberg J. Restless legs syndrome is common among female patients with fibromyalgia. Eur Neurol 2009;61:107-11

- Viola-Saltzman M, Watson NF, Bogart A, et al. High prevalence of restless legs syndrome among patients with fibromyalgia: a controlled cross-sectional study. J Clin Sleep Med 2010;6:423-7

- Holman AJ, Myers RR. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of pramipexole, a dopamine agonist, in patients with fibromyalgia receiving concomitant medications. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:2495-505

- Zoppi M, Maresca M. Symptoms accompanying fibromyalgia. Reumatismo 2008;60:217-20

- Frauscher B, Gschliesser V, Brandauer E, et al. The severity range of restless legs syndrome (RLS) and augmentation in a prospective patient cohort: association with ferritin levels. Sleep Med 2009;10:611-15

- Akyol A, Kiylioglu N, Kadikoylu G, et al. Iron deficiency anemia and restless legs syndrome: is there an electrophysiological abnormality? Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2003;106:23-7

- Allen RP, Auerbach S, Bahrain H, et al. The prevalence and impact of restless legs syndrome on patients with iron deficiency anemia. Am J Hematol 2013;88:261-4

- Allen RP, Burchell BJ, MacDonald B, et al. Validation of the self-completed Cambridge–Hopkins questionnaire (CH-RLSq) for ascertainment of restless legs syndrome (RLS) in a population survey. Sleep Med 2009;10:1097-100

- Spencer BR, Kleinman S, Wright DJ, et al. Restless legs syndrome, pica, and iron status in blood donors. Transfusion 2013;53:1645-52

- Arunthari V, Kaplan J, Fredrickson PA, et al. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome in blood donors. Mov Disord 2010;25:1451-5

- Ulfberg J, Nystrom B. Restless legs syndrome in blood donors. Sleep Med 2004;5:115-18

- Spencer B. Blood donor iron status: are we bleeding them dry? Curr Opin Hematol 2013;20:533-9

- Burchell BJ, Allen RP, Miller JK, et al. RLS and blood donation. Sleep Med 2009;10:844-9

- Bryant BJ, Yau YY, Arceo SM, et al. Ascertainment of iron deficiency and depletion in blood donors through screening questions for pica and restless legs syndrome. Transfusion 2013;53:1637-44

- Balendran J, Champion D, Jaaniste T, Welsh A. A common sleep disorder in pregnancy: restless legs syndrome and its predictors. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol 2011;51:262-4

- Neau JP, Marion P, Mathis S, et al. Restless legs syndrome and pregnancy: follow-up of pregnant women before and after delivery. Eur Neurol 2010;64:361-6

- Alves DA, Carvalho LB, Morais JF, Prado GF. Restless legs syndrome during pregnancy in Brazilian women. Sleep Med 2010;11:1049-54

- Suzuki K, Ohida T, Sone T, et al. The prevalence of restless legs syndrome among pregnant women in Japan and the relationship between restless legs syndrome and sleep problems. Sleep 2003;26:673-7

- Sikandar R, Khealani BA, Wasay M. Predictors of restless legs syndrome in pregnancy: a hospital based cross sectional survey from Pakistan. Sleep Med 2009;10:676-8

- Uglane MT, Westad S, Backe B. Restless legs syndrome in pregnancy is a frequent disorder with a good prognosis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2011;90:1046-8

- Hubner A, Krafft A, Gadient S, et al. Characteristics and determinants of restless legs syndrome in pregnancy: a prospective study. Neurology 2013;80:738-42

- Chen PH, Liou KC, Chen CP, Cheng SJ. Risk factors and prevalence rate of restless legs syndrome among pregnant women in Taiwan. Sleep Med 2012;13:1153-7

- Manconi M, Govoni V, De Vito A, et al. Restless legs syndrome and pregnancy. Neurology 2004;63:1065-9

- Lee KA, Zaffke ME, Baratte-Beebe K. Restless legs syndrome and sleep disturbance during pregnancy: the role of folate and iron. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 2001;10:335-41

- Sarberg M, Josefsson A, Wirehn AB, Svanborg E. Restless legs syndrome during and after pregnancy and its relation to snoring. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2012;91:850-5

- Tunc T, Karadag YS, Dogulu F, Inan LE. Predisposing factors of restless legs syndrome in pregnancy. Mov Disord 2007;22:627-31

- Dzaja A, Wehrle R, Lancel M, Pollmacher T. Elevated estradiol plasma levels in women with restless legs during pregnancy. Sleep 2009;32:169-74

- Djokanovic N, Garcia-Bournissen F, Koren G. Medications for restless legs syndrome in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2008;30:505-7

- Gigli GL, Adorati M, Dolso P, et al. Restless legs syndrome in end-stage renal disease. Sleep Med 2004;5:309-15

- Araujo SM, de Bruin VM, Nepomuceno LA, et al. Restless legs syndrome in end-stage renal disease: clinical characteristics and associated comorbidities. Sleep Med 2010;11:785-90

- Takaki J, Nishi T, Nangaku M, et al. Clinical and psychological aspects of restless legs syndrome in uremic patients on hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 2003;41:833-9

- Anand S, Johansen KL, Grimes B, et al. Physical activity and self-reported symptoms of insomnia, restless legs syndrome, and depression: the comprehensive dialysis study. Hemodial Int 2013;17:50-8

- Merlino G, Lorenzut S, Gigli GL, et al. A case–control study on restless legs syndrome in nondialyzed patients with chronic renal failure. Mov Disord 2010;25:1019-25

- Lee J, Nicholl DD, Ahmed SB, et al. The prevalence of restless legs syndrome across the full spectrum of kidney disease. J Clin Sleep Med 2013;9:455-9

- Aritake-Okada S, Nakao T, Komada Y, et al. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of restless legs syndrome in chronic kidney disease patients. Sleep Med 2011;12:1031-3

- Quinn C, Uzbeck M, Saleem I, et al. Iron status and chronic kidney disease predict restless legs syndrome in an older hospital population. Sleep Med 2011;12:295-301

- Enomoto M, Inoue Y, Namba K, et al. Clinical characteristics of restless legs syndrome in end-stage renal failure and idiopathic RLS patients. Mov Disord 2008;23:811-16; quiz 926

- Sloand JA, Shelly MA, Feigin A, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of intravenous iron dextran therapy in patients with ESRD and restless legs syndrome. Am J Kidney Dis 2004;43:663-70

- Besarab A, Coyne DW. Iron supplementation to treat anemia in patients with chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 2010;6:699-710

- Huiqi Q, Shan L, Mingcai Q. Restless legs syndrome (RLS) in uremic patients is related to the frequency of hemodialysis sessions. Nephron 2000;86:540

- Holley JL, Nespor S, Rault R. A comparison of reported sleep disorders in patients on chronic hemodialysis and continuous peritoneal dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 1992;19:156-61

- Roger SD, Harris DC, Stewart JH. Possible relation between restless legs and anaemia in renal dialysis patients. Lancet 1991;337:1551