Re: Coluzzi F, Ruggeri M. Clinical and economic evaluation of tapentadol extended release and oxycodone/naloxone extended release in comparison with controlled release oxycodone in musculoskeletal pain. Curr Med Res Opin 2014;30(6):1139-51

Dear Editor,

Pain is a normal human experience, but some people are hardwired physically, emotionally or both to progress to chronic pain states. Epidemiological studies suggest that around 20% of adults in Europe experience chronic painCitation1 and that its severity correlates with a reduction in physical and mental health. Severe chronic pain, in particular, presents a considerable burden for patients and can have a considerable impact on their quality of life, with a direct correlation to symptoms, such as anxiety, depression, and limited social functioningCitation1,Citation2. Effective pain management is considered as a fundamental human rightCitation3; however, more than one-third of such patients feel that their pain is inadequately managed and are dissatisfied with their treatmentCitation1.

Opioids are routinely prescribed for the treatment of chronic pain. In the past two decades there has been a massive increase in the number of opioid prescriptions, the daily opioid doses and overall opioid availability. Treating chronic pain with opioids has moved from being largely discouraged to being included as a standard of careCitation4 and titrating opioid doses up to self-reported adequate pain control by patients has become common practiceCitation5. Intersecting with the upward trajectory in opioid use are the increasing trends in opioid-related adverse effects, especially prescription drug abuse, addiction and even overdose deathsCitation6. Indeed, despite limited evidence and variable development methods, recent guidelines on chronic pain agree on several opioid risk mitigation strategies, which include upper dosing thresholds, cautions with certain medications, attention to drug–drug and drug–disease interactions and use of risk assessment toolsCitation7.

Despite the skilled use of opioid analgesics, the effective and safe treatment of chronic pain still remains an unmet clinical need and there is a strong demand for new drugs and new regimensCitation8. Novel opioids and/or opioid combinations have been marketed in recent years, including tapentadol and oxycodone/naloxone. Tapentadol is the first US FDA-approved centrally acting analgesic having both µ-opioid receptor agonist and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitory activity with minimal serotonin reuptake inhibition. This dual mode of action may make tapentadol particularly useful in the treatment of neuropathic pain. Its low affinity toward the µ-opioid receptors should also lead to a reduction in gastrointestinal adverse effects, namely nausea, vomiting and constipationCitation9. Constipation, experienced by some 40% of patients, is particularly challenging and – together with the other gastrointestinal symptoms – may dissuade patients from using the required analgesic dose to achieve effective pain reliefCitation10. The rationale for the oxycodone/naloxone combination (both compounds included in an oral extended-release formulation in a 2:1 fixed dose ratio) represents a new approach to counteract opioid-induced constipation, while maintaining effective analgesia. Following its release, naloxone acts locally on the gut, antagonizing the opioid binding to µ-receptors. After being absorbed in parallel with oxycodone, naloxone is rapidly and completely inactivated through a high first-pass effect in the liverCitation11,Citation12.

The experience with both medications is limited and these two approaches toward improved pain management have not to date been directly compared. Drs Coluzzi and RuggeriCitation13 therefore should be commended for their attempt to provide clinicians with an, albeit indirect, comparison of tapentadol extended release (ER) formulation and oxycodone/naloxone controlled release (CR) combination. The authors performed a meta-analysis and an economic evaluation of these two therapeutic strategies for the treatment of musculoskeletal pain through an indirect comparison with oxycodone CR. There are, however, several methodological and clinical issues that may affect the findings of the study and limit their validity and clinical relevance. Let us examine and comment on each of these issues.

The authors compared indirectly tapentadol ER and oxycodone/naloxone CR in the absence of any head-to-head randomized controlled trial (RCT). Indirect comparisons make important assumptions about the stability of relative treatment effects across RCTs. Indeed, RCTs might be performed in different populations, with different concomitant treatments, different overall management of disease, and, last but not least, different outcomes. Coluzzi and RuggeriCitation13 included three RCTs that compared oxycodone/naloxone CR with oxycodone CR. The first studyCitation14 enrolled patients with a documented history of moderate to severe chronic non-malignant lower back pain adequately managed by an opioid analgesic, and the aim was to demonstrate the superiority of oxycodone/naloxone CR formulation over placebo with respect to analgesic efficacy. This study also included an active group (i.e. patients treated with oxycodone CR) to compare the analgesic efficacy and the impact on bowel function of oxycodone/naloxone CR compared to oxycodone CR. The other two trialsCitation15,Citation16 were carried out in patients with moderate-to-severe non-cancer pain that required continued around-the-clock opioid therapy and who suffered from constipation induced by, or aggravated by, opioid therapy. The main aim of those studies was to evaluate the efficacy of oxycodone/naloxone CR compared to oxycodone CR in relieving constipation. On the contrary, all the trialsCitation17–19 evaluating tapentadol ER and included in the analysis of Coluzzi and RuggeriCitation13 had as primary goal the assessment of the efficacy and safety of this new medication compared to oxycodone CR. Furthermore, while patients of the oxycodone/naloxone trialsCitation14–16 were all on opioid therapy at the time of recruitment, between 44.0 and 49.8% of those belonging to the tapentadol studiesCitation17–19 were opioid naïve. Therefore, it is questionable to use data generated from studies which are clearly heterogeneous.

How should an indirect clinical comparison be performed? Certainly, not by putting ‘apples and oranges’ togetherCitation20. Indeed, a fundamental principle of meta-analysis is to analyze data from homogenous populations with the very same outcome. As a consequence, the approach followed by the authors is flawed. One simple method is to compare the results of individual arms from different studies as if they were from the same RCT. An example of this approach is presented in . If one evaluates four variables selected from the studies Coluzzi and RuggeriCitation13 included in their analysis, it appears that oxycodone/naloxone CR has a significantly better profile than tapentadol ER. Nevertheless, this kind of unadjusted indirect comparison has been criticized for discarding within trial comparisons, increasing the liability of bias and over-precise estimatesCitation22. A more robust methodological approach is to carry out an adjusted comparison using network meta-analysis, which takes into account the inferences about the relative merits of the treatments that have never been comparedCitation23,Citation24.

Table 1. Unadjusted comparison between tapentadol ER and oxycodone/naloxone CR (Oxy/Nal).

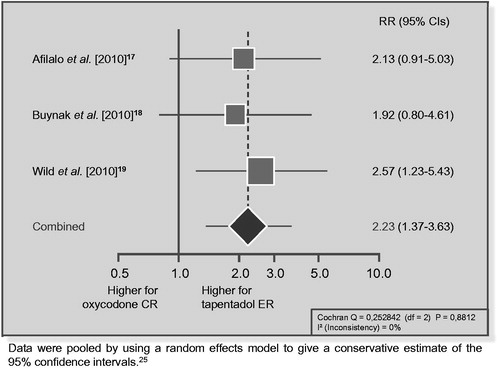

One of the statements of the Markov model proposed by Coluzzi and RuggeriCitation13 is designated as ‘discontinuation’. They likely refer to discontinuation due to adverse events, since they presented the results for this variable in their meta-analysis. However, even if the authors took into account the variable ‘discontinuation due to lack of efficacy’, it is not clear whether they considered that variable in terms of efficacy. In the trials evaluating tapentadol ER versus oxycodone CRCitation17–19, the risk ratio (RR) of discontinuing the treatment due to lack of efficacy was significantly greater for tapentadol ER () whereas the RR of oxycodone/naloxone CR was similar to that of oxycodone CR (RR = 0.91, 95% CI: 0.36–2.32). Since, in pharmacovigilance terms, drug failure is considered a type F adverse eventCitation26, this increased likelihood of ineffectiveness of tapentadol should also translate into a worse adverse effect profile.

Figure 1. Risk of discontinuation due to lack of efficacy in trials comparing tapentadol ER with oxycodone CR: a meta-analysis.

In their study, the authors analyzed the incidence of constipation during treatment. This is correct for the RCTs evaluating tapentadol ERCitation17–19, but might be questioned for two of the trialsCitation15,Citation16 evaluating oxycodone/naloxone CR. As already emphasized, the aim of those trials was to evaluate the efficacy of oxycodone/naloxone CR compared to oxycodone CR in relieving opioid-induced constipation, assessed using the Bowel Function Index (BFI). Both studies showed a significant improvement in BFI and, therefore, the data regarding constipation presented in the forest plot (Figure 5 of the Coluzzi and Ruggeri paperCitation13) do not reflect the aim of the studies and – when included in an economic model – could produce ambiguous findings.

Finally, among the adverse events (AEs), the authors considered those related to the gastrointestinal system (GIS), to the central nervous system (CNS) and to the skin, as stated in of their articleCitation13. However, data on AEs concerning the skin are not presented or discussed. Furthermore, it is not clear why they decided to consider AEs separately instead of just considering the ‘overall’ number of AEs observed during the study for each treatment.

In summary, although commendable, the paper of Coluzzi and RuggeriCitation13 fails to reach the aim of the study, which was to provide clinicians with an objective evaluation of the clinical and economic impact of tapentadol ER, in comparison with oxycodone/naloxone CR, in patients with muscoloskeletal pain. Indeed, their conclusion that tapentadol ER is more cost-effective is not supported by a critical evaluation of the available literature. Only a large, well designed, prospective, clinical trial affording a direct head-to-head comparison between these two medications will provide a reliable comparison of their cost-effectiveness. For now, taking these conclusions into account when making therapeutic choices would be like building castles in the air, whose crash will have disastrous consequences. A dispassionate look at the current data will doubtless lead the reader to agree with our viewpoint.

Sincerely,

Carmelo Scarpignato MD DSc PharmD MPH FRCP (London) FACP FCP FACG AGAF

Clinical Pharmacology & Digestive Pathophysiology Unit Department of Clinical & Experimental Medicine

University of Parma, Italy

Luigi Gatta MD

Gastroenterology and Endoscopy Unit

Versilia Hospital, Lido di Camaiore, Italy

Clinical Pharmacology & Digestive Pathophysiology Unit

Department of Clinical & Experimental Medicine

University of Parma, Italy

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This letter was not funded.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

C.S. has disclosed that he is a member of Mundipharma Pharmaceuticals and Pfizer Speaker’s Bureau. L.G. has disclosed that he has no significant relationships with or financial interests in any commercial companies related to this study or article.

References

- Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, et al. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain 2006;10:287-333

- Kroenke K, Outcalt S, Krebs E, et al. Association between anxiety, health-related quality of life and functional impairment in primary care patients with chronic pain. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2013;35:359-65

- Brennan F, Carr DB, Cousins M. Pain management: a fundamental human right. Anesth Analg 2007;105:205-21

- Boudreau D, Von Korff M, Rutter CM, et al. Trends in long-term opioid therapy for chronic non-cancer pain. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2009;18:1166-75

- Sarzi-Puttini P, Vellucci R, Zuccaro SM, et al. The appropriate treatment of chronic pain. Clin Drug Investig 2012;32(Suppl 1):21-33

- Okie S. A flood of opioids, a rising tide of deaths. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1981-5

- Nuckols TK, Anderson L, Popescu I, et al. Opioid prescribing: a systematic review and critical appraisal of guidelines for chronic pain. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:38-47

- Varrassi G, Marinangeli F, Piroli A, et al. Strong analgesics: working towards an optimal balance between efficacy and side effects. Eur J Pain 2010;14:340-2

- Hartrick CT, Rozek RJ. Tapentadol in pain management: a mu-opioid receptor agonist and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor. CNS Drugs 2011;25:359-70

- Camilleri M. Opioid-induced constipation: challenges and therapeutic opportunities. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:835-42

- Mueller-Lissner S. Fixed combination of oxycodone with naloxone: a new way to prevent and treat opioid-induced constipation. Adv Ther 2010;27:581-90

- Mercadante S, Giarratano A. Combined oral prolonged-release oxycodone and naloxone in chronic pain management. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2013;22:161-6

- Coluzzi F, Ruggeri M. Clinical and economic evaluation of tapentadol extended release and oxycodone/naloxone extended release in comparison with controlled release oxycodone in musculoskeletal pain. Curr Med Res Opin 2014;30:1139-51

- Vondrackova D, Leyendecker P, Meissner W, et al. Analgesic efficacy and safety of oxycodone in combination with naloxone as prolonged release tablets in patients with moderate to severe chronic pain. J Pain 2008;9:1144-54

- Simpson K, Leyendecker P, Hopp M, et al. Fixed-ratio combination oxycodone/naloxone compared with oxycodone alone for the relief of opioid-induced constipation in moderate-to-severe noncancer pain. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:3503-12

- Lowenstein O, Leyendecker P, Hopp M, et al. Combined prolonged-release oxycodone and naloxone improves bowel function in patients receiving opioids for moderate-to-severe non-malignant chronic pain: a randomised controlled trial. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2009;10:531-43

- Afilalo M, Etropolski MS, Kuperwasser B, et al. Efficacy and safety of tapentadol extended release compared with oxycodone controlled release for the management of moderate to severe chronic pain related to osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled phase III study. Clin Drug Investig 2010;30:489-505

- Buynak R, Shapiro DY, Okamoto A, et al. Efficacy and safety of tapentadol extended release for the management of chronic low back pain: results of a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled Phase III study. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2010;11:1787-804

- Wild JE, Grond S, Kuperwasser B, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of tapentadol extended release for the management of chronic low back pain or osteoarthritis pain. Pain Pract 2010;10:416-27

- Sharpe D. Of apples and oranges, file drawers and garbage: why validity issues in meta-analysis will not go away. Clin Psychol Rev 1997;17:881-901

- Newcombe R, Altman D. Proportion and their differences. In: Altman DG, Machin D, Trevor NB (eds). Statistics with Confidences, 2nd edn. London: BMJ Books, 2000:45-56

- Glenny AM, Altman DG, Song F, et al. Indirect comparisons of competing interventions. Health Technol Assess 2005;9:1-134, iii-iv

- Lumley T. Network meta-analysis for indirect treatment comparisons. Stat Med 2002;21:2313-24

- Caldwell DM, Ades AE, Higgins JP. Simultaneous comparison of multiple treatments: combining direct and indirect evidence. BMJ 2005;331:897-900

- DerSimonian R, Kacker R. Random-effects model for meta-analysis of clinical trials: an update. Contemp Clin Trials 2007;28:105-14

- Edwards IR, Aronson JK. Adverse drug reactions: definitions, diagnosis, and management. Lancet 2000;356:1255-9