Abstract

Objective To assess basal insulin persistence, associated factors, and economic outcomes for insulin-naïve people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in the US.

Research design and methods People aged ≥18 years diagnosed with T2DM initiating basal insulin between April 2006 and March 2012 (index date), no prior insulin use, and continuous insurance coverage for 6 months before (baseline) and 24 months after index date (follow-up period) were selected using de-identified administrative claims data in the US. Based on whether there were ≥30 day gaps in basal insulin use in the first year post-index, patients were classified as continuers (no gap), interrupters (≥1 prescription after gap), and discontinuers (no prescription after gap).

Main outcome measures Factors associated with persistence – assessed using multinomial logistic regression model; annual healthcare resource use and costs during follow-up period – compared separately between continuers and interrupters, and continuers and discontinuers.

Results Of the 19,110 people included in the sample (mean age: 59 years, ∼60% male), 20% continued to use basal insulin, 62% had ≥1 interruption, and 18% discontinued therapy in the year after initiation. Older age, multiple antihyperglycemic drug use, and injectable antihyperglycemic use during baseline were associated with significantly higher likelihoods of continuing basal insulin. Relative to interrupters and discontinuers, continuers had fewer emergency department visits, shorter hospital stays, and lower medical costs (continuers: $10,890, interrupters: $13,674, discontinuers: $13,021), but higher pharmacy costs (continuers: $7449, interrupters: $5239, discontinuers: $4857) in the first year post-index (p < 0.05 for all comparisons). Total healthcare costs were similar across the three cohorts. Findings for the second year post-index were similar.

Conclusions The majority of people in this study interrupted or discontinued basal insulin treatment in the year after initiation; and incurred higher medical resource use and costs than continuers. The findings are limited to the commercially insured population in the US. In addition, persistence patterns were assessed using administrative claims as opposed to actual medication-taking behavior and did not account for measures of glycemic control. Further research is needed to understand the reasons behind basal insulin persistence and the implications thereof, to help clinicians manage care for T2DM more effectively.

Introduction

The annual cost of treating people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), the most common form of diabetes that affects about 26% of persons aged 65 years and older in the US, has been estimated to be $245 billion in the USCitation1. While much of the estimated healthcare cost is attributable to treatment of diabetes itself, a substantial amount of the cost is for the treatment of chronic complications arising as a result of poor glycemic controlCitation2. Therefore, maintaining adequate glycemic control among people with T2DM is very important for patients, providers, payers and other healthcare decision makers. The consensus-based guidelines provided by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommend a step-wise treatment algorithm for effective management of T2DMCitation3. According to this algorithm, when lifestyle and diet modifications are inadequate to maintain glycemic control, people with T2DM initiate treatment with metformin. Other oral antihyperglycemic medications (e.g., sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 [DPP-4] inhibitors) and/or non-insulin injectable medications (i.e., glucagon-like peptide-1 [GLP-1] receptor agonists) may subsequently be added to the regimen to manage adequate glycemic control, as necessary. Due to the progressive nature of the disease, people with T2DM may eventually require insulin as a part of their treatment regimenCitation4. ADA guidelines recommend initiating insulin with a long-acting basal insulin analog monotherapy (i.e., glargine and detemir) which is considered the most convenient insulin regimen. Depending on the degree of hyperglycemia, insulin treatment may need to be intensified using prandial insulin or supplemented with a GLP-1 receptor agonistCitation3. Intensive insulin treatment has been shown to be the most effective therapy in lowering blood glucose levels which in turn helps prevent or delay the development of micro- and macrovascular complications of diabetesCitation5,Citation6.

Despite guideline recommendations and demonstrated benefits of insulin therapy in people with T2DM, substantial proportions of people do not achieve adequate glycemic control following insulin initiationCitation7–9. This may in part be due to suboptimal persistence with insulin treatment in the real world care setting. For example, in a study of a large commercially insured insulin-naïve population in the US, Ascher-Svanum et al. found that only 18% of the people with T2DM who initiated insulin continued treatment in the year after initiation without any interruption or discontinuationCitation10. With regards to basal insulin in particular, studies have found that approximately 55–80% of people with T2DM (identified from large commercial insurance databases) who were prescribed insulin glargine remained treatment persistent within the year after initiationCitation11–14. In a separate study evaluating persistence with injectable antihyperglycemic medications among a managed care population, Cooke et al. reported that 29% of patients initiating basal insulin or exenatide were persistent at 12 months after initiationCitation15. In yet another study, Bonafede et al. found that 27% of basal insulin initiators had uninterrupted use in the year after initiationCitation16. More recently, using pooled data from three different retrospective analyses of commercially insured populations, Wei et al. reported that 65% of the people using insulin glargine or insulin detemir were treatment persistent within the year after initiationCitation17. This variability in persistence estimates may be attributable to different definitions of persistence. For example, Ascher-Svanum et al. and Cooke et al. considered people to be persistent if they refilled their prescription within 30 days of the end of (anticipated) days’ supply of the existing prescription. By comparison, both Wei et al. and Baser et al. defined persistence as refilling the prescription within the 90th percentile of the time between the first and second refills among those with at least two refills, stratified by quantity suppliedCitation11. In all instances, however, people with an extended gap in insulin treatment were considered non-persistent even if they restarted therapy after initial discontinuation; a pattern commonly observed among people using insulin in the real worldCitation10. Therefore, it is important to gain a better understanding of the rates of basal insulin interruption and discontinuation separately.

In addition, while studies have attempted to gain a better understanding of the factors associated with insulin persistence using administrative claims data, to the best of our knowledge, no study has evaluated the factors associated with treatment interruption separately. Furthermore, there remains an inconsistency in the findings of previous studies that evaluated factors associated with insulin persistence. For example, older age has been consistently shown to be associated with increased likelihoods of insulin persistenceCitation10,Citation15,Citation17. Two studies found a significant association between other factors such as male gender, use of multiple classes of antihyperglycemic medications, and use of multiple classes of all-cause medications during baseline with increased likelihoods of persistenceCitation10,Citation16, while another study did not.Citation15

With regards to the outcomes of insulin non-persistence, the literature has consistently documented that discontinuation of insulin therapy was associated with increased use of medical services, especially acute care, and lower pharmacy use in the year after insulin initiation compared with continuation of treatment as prescribedCitation10,Citation12,Citation17. However, because the majority of patients use insulin intermittently (as opposed to discontinuing altogether) and therefore possibly continue to attain some benefits associated with insulin treatment, there is a need to understand the implications associated with treatment interruption and discontinuation separately, relative to continuous use.

The goal of the present study was to provide a better understanding of basal insulin persistence, specifically with regards to treatment continuation, interruption, and discontinuation within a year of insulin initiation among commercially insured patients in the US. For each of the three cohorts mentioned above, persistence rates were also evaluated in the second year after insulin initiation. In addition, the study aimed to assess the factors associated with continuation, interruption, and discontinuation of basal insulin use in the year after treatment initiation and their implications on annual healthcare resource use and costs during the two years after treatment initiation.

Methods

Data and sample selection

De-identified administrative claims from OptumHealth Reporting and Insights, a database containing information on medical services provided between 1 January 1999 and 31 March 2014 for approximately 18 million beneficiaries (including employees, spouses, dependents, and retirees) from over 80 US-based companies, were used for this analysis.

The population of interest consisted of adult (at least 18 years old) beneficiaries with T2DM who initiated non-mixed basal insulin (insulin glargine, insulin detemir, insulin isophane) only, between 1 April 2006 and 31 March 2012. Initiation of basal insulin was defined as no previous insulin use in the 6 months prior to the first non-mixed basal insulin claim. To ensure patients initiated insulin treatment with basal insulin only, those with evidence of other insulin on the date of their first non-mixed basal insulin claim were excluded. The date of the first claim for non-mixed basal insulin at any time in the patient’s history was defined as the index date, the 6 month period prior to index date as the baseline period, and the 24 month period following the index date as the follow-up period. Beneficiaries were required to have continuous enrollment in health plans other than health maintenance organizations (HMOs) throughout the baseline and follow-up periods. Beneficiaries with a diagnosis of secondary diabetes, pregnancy, or gestational diabetes were excluded.

Beneficiaries were identified as having T2DM if they met any of the following conditions: (1) at least two diagnoses for T2DM (ICD 9-CM: 250.x0 or 250.x2) and fewer diagnoses for type 1 diabetes (ICD 9-CM: 250.x1 or 250.x3) than T2DM in the 18 month period comprising the baseline and first 12 months of the follow-up period; or (2) at least one diagnosis of T2DM during the 18 month period and at least one prescription for non-insulin antihyperglycemic medication (other than pramlintide) in the 6 month baseline period (an approach consistent with prior researchCitation18).

Basal insulin persistence

Basal insulin persistence was defined as having no gaps of ≥30 days in basal insulin supply during year 1 of the follow-up period, where basal insulin could be the index insulin, other non-mixed basal insulin, or pre-mixed basal insulin. The gap is defined as the days between the end of one prescription (based upon fill date and days supplied) and the earliest of the fill date for a subsequent prescription or the end of year 1. The final analytic sample was classified into three mutually exclusive cohorts: (1) continuers or persistent users (as defined above), (2) interrupters – those with at least one basal insulin claim after the first ≥30 day gap during year 1 (independent of whether they subsequently discontinued treatment), and 3) discontinuers – those with no basal insulin claims after the first ≥30 day gap in basal insulin use during year 1. Within each cohort, persistence patterns in the second year after treatment initiation were also assessed using similar classifications as year 1 for those with at least one basal insulin prescription in the second year. People with no basal insulin prescriptions in year 2 were classified as non-users.

In order to better characterize basal insulin use among the interrupters, the number and duration of gaps during the 2 year follow-up period were estimated. Discontinuation of treatment following an earlier interruption was also considered a gap in therapy for the analyses of number and duration of gaps.

Time to first interruption, defined as the time between basal insulin initiation and the day prior to the first ≥30 day gap in basal insulin supply, was estimated using Kaplan–Meier analysis. Data for discontinuers was censored at the time of discontinuation. Similar analysis was performed to estimate time to discontinuation, with data for interrupters censored at the time of first interruption. Data for continuers were censored at 12 months for both analyses.

Baseline characteristics

Differences in demographics (mean age, gender, and the geographic location [US Census region]Citation19 at the time of treatment initiation), type of basal insulin used at treatment initiation (analog vs. human), mode of index basal insulin delivery (i.e., pen, vial, cartridges), Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)Citation20, and presence of microvascular and macrovascular comorbidities, depression, obesity, other neurological disorders, hypoglycemic events, or dementia during the 6 month baseline period were separately evaluated between continuers and interrupters, and continuers and discontinuers. Measures of medical resource use (frequency and likelihood of hospitalizations, emergency department visits, outpatient/physician office visits, endocrinologist visits) as well as prescription drug use (antihyperglycemic medication use: overall and by class of medication; number of unique classes used, proportions using antihypertensives, statins, antidepressants, or antiplatelet agents), during the baseline were also compared across cohorts. Statistical significance of differences was evaluated using chi-squared tests for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables. Statistical significance was defined as p <0.05.

Outcomes and statistical analyses

Factors associated with basal insulin persistence

Factors associated with basal insulin interruption and discontinuation were identified using a multinomial logistic regression model (with continuous use as the reference category). All patient characteristics evaluated during the 6 month period prior to basal insulin treatment initiation and at index date (as described above) were considered as potential factors associated with basal insulin persistence.

Medical resource use and costs associated with basal insulin persistence

Annual medical resource use stratified by place of service (i.e., hospitalizations, emergency department visits, outpatient/physician office visits, other visits) as well as antihyperglycemic medication use in year 1 and year 2 were compared between continuers and interrupters, and continuers and discontinuers. Both all-cause resource use and diabetes-related resource use (defined as claims with ICD 9-CM: 250.x0 or 250.x2) were evaluated.

In addition, for people aged <65 years, all-cause and diabetes-related medical, pharmacy, and total healthcare costs from a payer perspective were compared across the cohorts of interest. Diabetes-related costs included costs associated with diabetes-related medical claims and antihyperglycemic prescription medications. Costs were not evaluated for those aged ≥65 years because the database only contains information on costs to commercial insurers, which may often be equal to $0 for people aged ≥65 years (due to Medicare coverage), and would result in inaccurate cost estimates for everyone combined.

Differences in underlying characteristics between cohorts were accounted for using a propensity score-based inverse probability weighting (IPW) methodCitation21. As with other propensity score-based approaches, the propensity (i.e., likelihood) of being in a given cohort as a function of observed baseline characteristics was estimated using a multinomial logistic regression model. All baseline and index date characteristics were included as potential independent covariates. Following the computation of propensity scores, each person was attributed a weight defined as the inverse of the propensity score for that person. The weighted baseline characteristics were evaluated to ensure that no important differences remained across cohorts. Statistical comparisons were made between continuers vs. interrupters and continuers vs. discontinuers using weighted t-tests for continuous measures and weighted chi-squared tests for categorical variables. Finally, the medical/prescription drug-related resource use and cost outcomes were compared across continuers vs. interrupters, and continuers vs. discontinuers using similar statistical tests as described above.

Medication use during the first gap in treatment

The proportions of interrupters and discontinuers using the various classes of antihyperglycemic medications during the first gap in treatment were evaluated. Prescriptions filled prior to the start of the first gap but with days of supply that overlapped with the gap were included. No comparisons were made within or between the cohorts.

Sensitivity analyses involving definition of basal insulin persistence

Considering that patient-specific insulin dosage depends on a variety of factors, it is possible that people with a dispensed days’ supply of, for example, 30 days might, in reality, use the filled medication for more or less than 30 days. Thus, estimating persistence with insulin therapy may not be as straightforward as with other fixed-dose drugs (e.g., oral medications). As a sensitivity analysis, the study estimated the proportions of patients characterized as continuers versus interrupters or discontinuers in the first year after treatment initiation, allowing for gaps of up to 60, 90, and 120 days between available days’ supply. In addition, the study estimated persistence patterns in the first year after treatment initiation using an alternative definition of persistence that has been used in the literatureCitation11,Citation12,Citation13,Citation14,Citation17, allowing for time between refills that is less than the 90th percentile of the duration between consecutive basal insulin prescription fills for the sample, stratified by quantity supplied (<1500 units, 1500–<3000 units, and ≥3000 units).

Results

Basal insulin persistence

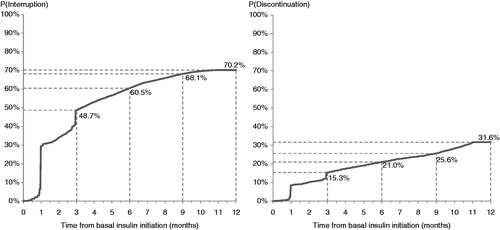

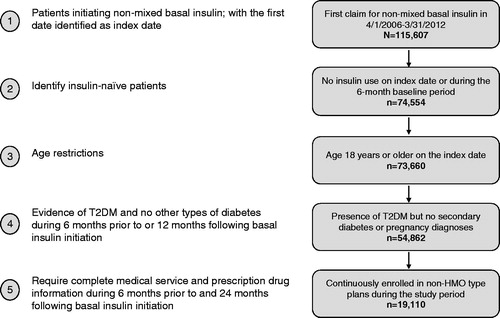

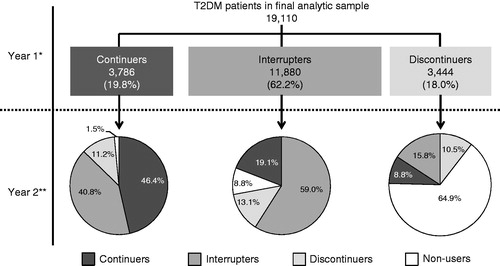

A total of 19,110 people were included in the final analytic sample (). During the first year after treatment initiation, 20% of the people used basal insulin continuously, 62% had a gap of ≥30 days between prescriptions, and 18% discontinued therapy after the first gap of ≥30 days (). In the second year, 46% of the continuers used basal insulin without any interruption, 41% used it intermittently, and the remaining discontinued therapy. Among the interrupters in the first year, 59% also had a gap of ≥30 days in the second year, 19% started using the medication continuously, 13% discontinued therapy, and 8% did not use basal insulin. Most discontinuers in the first year (65%) did not re-initiate basal insulin in the second year post-index (non-users), 16% re-initiated but used it intermittently, and 10% re-initiated but discontinued again (). During the 2 year follow-up period, interrupters had on average 3.4 gaps (standard deviation [SD]: 1.7), with a mean duration of 95.4 days (SD: 92.8). In regard to timing of interruption, over two-thirds of the interrupters (73%) had their first gap within 90 days of treatment initiation. Based on the Kaplan–Meier analysis that adjusted for censoring, the median time to treatment interruption was 3.3 months and the estimated probability of interruption within 3 months was 49% (). Among the discontinuers, 67% discontinued basal insulin within the first 90 days of treatment initiation. In the Kaplan–Meier analysis, the median time to discontinuation was not reached and there was a 15% probability of discontinuing treatment within 3 months after initiation ().

Figure 1. Sample selection and resulting patient counts. HMO = health maintenance organization; Non-mixed basal insulin are insulin detemir, glargine, and NPH (neutral protamine Hagedorn) insulin; T2DM was identified using ICD-9 CM codes 250.x0 and 250.x2; T1DM was identified using ICD-9 CM codes 250.x1 and 250.x3, secondary diabetes as ICD-9 CM: 249.xx, and pregnancy as ICD-9 CM: 630.xx – 679.xx, V22.xx – V24.xx, V27.xx, V29.xx.

Figure 2. Basal insulin persistence patterns in years 1 and 2 after treatment initiation. *In year 1, 73.3% of the interrupters had their first gap of <30 days in basal insulin use and 67.5% of the discontinuers had discontinued basal insulin within 90 days of treatment initiation. **In year 2, patterns of use were evaluated beginning on the first day of basal or mixed insulin use during the second 12 months of the follow-up period. Those with no basal or mixed insulin use during the second 12 months were considered non-users. Over the entire 2 year follow-up period, those classified as interrupters in year 1 had 3.4 gaps with an average duration of 95.4 days per gap.

Baseline characteristics

At baseline, continuers were statistically significantly older (60 years [SD: 10.7] vs. 59 years for interrupters [SD: 12.3] and discontinuers [SD: 13.4]), more likely to be male (62% vs. 59% interrupters and 60% discontinuers), and had lower mean CCI relative to the interrupters and discontinuers (). In addition, continuers used more classes of non-insulin antihyperglycemic medications but used significantly fewer medical services, including visits to an endocrinologist in the 6 month baseline period relative to the other two cohorts (). Within each cohort, ∼74% of the people initiated treatment with insulin glargine, ∼21% with insulin detemir, and the remaining with NPH insulin. In addition, most patients, independent of the cohort, used a basal insulin pen at the time of treatment initiation (compared to vials; ).

Table 1. Baseline patient characteristics.

Factors associated with treatment interruption and discontinuation

Multivariable models indicated that the following factors were associated with significantly higher likelihoods of treatment interruption and discontinuation: younger age, female gender, presence of diabetic foot complications or neurological disorders, and having at least one endocrinologist visit or inpatient or emergency department (ED) visit prior to basal insulin initiation. Factors that were associated with significantly lower likelihoods of treatment interruption and discontinuation included: presence of dyslipidemia, use of multiple classes of antihyperglycemic medications, and injectable antihyperglycemic drugs other than insulin during baseline ().

Table 2. Factors associated with treatment interruption and discontinuation relative to continuation in the year after initiation.

Follow-up period outcomes

Although the three cohorts were different on nearly all baseline characteristics evaluated, the inverse probability weighting resulted in cohorts with similar characteristics (Supplementary Appendix Table 1).

All-cause resource use and costs

After accounting for underlying differences, overall (i.e., for all causes) continuers had fewer ED visits (0.6 [SD: 1.4] vs. 0.8 [SD: 2.1] for interrupters and 0.8 [SD: 1.9] for discontinuers) and shorter hospital stays (7.5 [SD: 18.1] vs. 9.6 [SD: 25.6] for interrupters and 9.6 [SD: 22.1] for discontinuers) in the year after treatment initiation compared with interrupters and discontinuers (). However, continuers had a higher number of all-cause outpatient/physician office visits (17.6 [SD: 15.3] vs. 16.7 [SD: 14.7] for interrupters and 16.5 [SD: 15.7] for discontinuers) and used more medications (of any type) during the year than interrupters and discontinuers (). All comparisons were statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Table 3. Adjusted healthcare resource use and costs in the first year after treatment initiation.

Consequently, among people with complete cost data (i.e., those aged <65 years throughout the study period), continuers had statistically significantly higher all-cause pharmacy costs than interrupters and discontinuers ($7449 [SD: $7181] vs. $5239 [SD: $7274] for interrupters and $4857 [SD: $11,484] for discontinuers), but lower all-cause medical costs ($10,893 [SD: $26,631] vs. $13,674 [SD: $44,994] for interrupters and $13,021 [SD: $35,092] for discontinuers), resulting in similar total healthcare costs across the three cohorts ().

During the second year of follow-up, the all-cause resource use comparisons were similar to those seen in year 1: continuers (as defined in year 1) had fewer ED visits and shorter inpatient stays (vs. interrupters only), but used more outpatient/physician services and medications than interrupters and discontinuers (all comparisons were statistically significant [p < 0.05]). With regard to costs, continuers had statistically significantly higher pharmacy costs than interrupters and discontinuers, but the medical costs were similar across the three cohorts. The total healthcare costs were similar for continuers and interrupters but statistically significantly higher for continuers than discontinuers (Supplementary Appendix Table 2).

T2DM-related resource use and costs

Continuers had fewer T2DM-related ED visits than interrupters and discontinuers (0.1 [SD: 0.5] vs. 0.2 [SD: 0.5] and 0.1 [SD: 0.5] respectively) in the year after treatment initiation. In addition, continuers had fewer T2DM-related inpatient days than interrupters (3.1 [SD: 11.4] vs. 4.0 [SD: 16.4]). Of note, fewer continuers had T2DM-related ED visits and hospitalizations for hypoglycemic events during the year after initiating basal insulin compared to interrupters and discontinuers (). All comparisons were statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Compared with interrupters, continuers had significantly higher T2DM-related pharmacy costs but significantly lower T2DM-related medical costs. As a result, the total T2DM-related costs were similar for the two cohorts (). Continuers also had significantly higher T2DM-related pharmacy costs than discontinuers. However, the two cohorts had similar medical costs, resulting in significantly higher total T2DM-related costs for continuers ().

During year 2, T2DM-related medical resource use and costs were similar between continuers versus interrupters and discontinuers. However, continuers had higher rates of antihyperglycemic medication use than interrupters and discontinuers, which was associated with higher T2DM-related pharmacy costs as well as total (medical plus pharmacy) T2DM-related costs for this cohort (all comparisons statistically significant [p < 0.05], Supplementary Appendix Table 2).

Medication use during the first gap

During the first gap, the majority of interrupters and discontinuers used at least one antidiabetic medication other than basal insulin. Specifically, approximately 9% of the interrupters and 10% of discontinuers used a non-basal insulin, 7% of the interrupters and 9% of the discontinuers used non-insulin injectable medications, and 77% of both groups used oral antidiabetic medications during the gap (Supplementary Appendix Table 3).

Sensitivity analyses

Results of the sensitivity analyses suggest that the proportions of people characterized as continuers or interrupters/discontinuers during the first year after treatment initiation depend, to a great extent, on the length of allowable gaps in basal insulin use. For example, allowing for 60 day gaps in basal insulin use would characterize 40% of people as continuers, 39% as interrupters, and 21% as discontinuers (Supplementary Appendix Table 4). Not surprisingly, the persistence rates increase even further when extending the gap length to 90 days (55%) and 120 days (65%). Allowing for gaps shorter than the 90th percentile of days between two consecutive prescription fills during the first year after basal insulin initiation would characterize 44% of the sample as continuers, 35% as interrupters, and 21% as discontinuers (Supplementary Appendix Table 4).

Discussion

In this study, the majority of the people with T2DM who initiated basal insulin either used it intermittently (62%) or discontinued (18%) within the first year of treatment initiation; with over two-thirds doing so within the first 90 days of beginning therapy. In addition, only 46% of people with continuous use in the first year also had uninterrupted basal insulin use in the second year of follow-up. By comparison, 59% of interrupters also interrupted basal insulin treatment in the subsequent year, and 65% of discontinuers did not restart the therapy for at least one more year. The rates of persistence observed in this study (about 20%) are similar to those reported by Ascher-Svanum et al.Citation10, Cooke et al.Citation15, and Bonafede et al.Citation16, but lower than some other estimates in the literatureCitation11,Citation12,Citation17. For example, Wei et al. found that two-thirds of the patients initiating treatment with insulin glargine or detemir continued treatment for the full yearCitation17. In a different study, Baser et al. estimated a persistence rate of 56% for people initiating treatment with insulin glargineCitation11. This variability in persistence estimates may be attributable to the different definitions of persistence. For example, the definition of persistence for the present analysis is similar to the approach used by Ascher-Svanum et al., Cooke et al., and Bonafede et al., resulting in similar estimates across the studies. In contrast, both Wei et al. and Baser et al. defined persistence as refilling the prescription within the 90th percentile of the time between the first and second refills among those with at least two refills, stratified by quantity supplied. Findings from the sensitivity analyses in the current analysis also demonstrate the effects of using different criteria used to characterize persistence: allowing for gaps in basal insulin use of up to 60 days, 90 days, 120 days, or shorter than 90th percentile of the days between two consecutive fills would respectively characterize 40%, 55%, 65%, and 44% of the sample as being persistent within the year after treatment initiation.

We also find that the characteristics of people differ across basal insulin persistence patterns. Multinomial regression results suggest that older age, male gender, multiple antihyperglycemic drug use, and injectable antihyperglycemic medication use before insulin initiation are associated with a significantly higher likelihood of continuing basal insulin in the year after initiation; whereas presence of diabetic foot complications or neurological disorders (other than depression and dementia) and higher medical resource use before insulin initiation are associated with a significantly lower likelihood of insulin continuation. The finding that older age and use of other antihyperglycemic medications, particularly injectables, during baseline is associated with increased likelihoods of persistence is similar to previous studiesCitation10,Citation17. In addition, as noted by Wei et al., having experience using injectables might alleviate the fear of injections and increase confidence in using other injectable medications such as insulin in the future, resulting in greater persistence. The association between use of multiple antihyperglycemic medications prior to insulin initiation and greater persistence could likely be explained by increased awareness regarding benefits of insulin therapy and implications of poor glycemic control. Another explanation could stem from the fact that persistent people (i.e., continuers) had higher medication use and lower comorbidity rates as well as medical resource use prior to basal insulin initiation; all of which suggest that these patients may generally be more likely to adhere to treatment regimens. Future research should evaluate the association between basal insulin persistence and self-reported factors such as patient education and adherence to other medications.

Prior to this analysis, several studies have evaluated the economic consequences associated with insulin non-persistenceCitation10,Citation12,Citation17. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that stratifies these findings by whether the patients had gaps in treatment or discontinued therapy altogether. For example, Ascher-Svanum et al. found that discontinuing treatment (for at least 30 days) within the first 90 days of initiation resulted in 9.6% higher acute care (hospitalization and ED) costs than those who continued treatment. In addition, the study found that the costs of those restarting therapy after initial discontinuation (approximately 90% of the sample) were higher than those who did not restart therapy within the remainder of the follow-up period. However, the study did not compare the resource use and costs of those restarting treatment after initial discontinuation to persistent patients. In our study, we find that continuers used fewer medical services (e.g., fewer ED visits and shorter hospital stays) and therefore had fewer medical costs during the follow-up period from a payer’s perspective, compared with both interrupters and discontinuers (). While we did not compare the results between interrupters and discontinuers, the study findings provide important insight regarding the significance of basal insulin persistence. Contrary to the belief that people restarting insulin may continue to receive some benefits associated with insulin therapy, our findings suggest that any interruption in treatment, even if subsequently reinitiated, may be associated with outcomes requiring more acute care in the two years that immediately follow treatment initiation.

Taken together the study findings suggest that, for a subset of patients who are at increased risk of treatment interruption and discontinuation, developing interventions to improve persistence early in the course of therapy may result in better patient outcomes in the subsequent two years. However, further research is needed to evaluate the long-term outcomes associated with these treatment patterns as many of the implications of glycemic control (e.g., macrovascular complications) are not realized immediately. In addition, the specific mechanisms behind the association between resource use and costs and persistence to basal insulin need to be evaluated in the future. For example, we find that nearly twice as many beneficiaries interrupting and discontinuing basal insulin required acute care for hypoglycemic events during the year after treatment initiation, compared with continuers. But it is not clear whether these events manifested after the interruption/discontinuation or might potentially have contributed to having gaps in treatment.

The study also had additional limitations. First, the analyses relied on the accuracy and completeness of administrative claims data for identifying people with T2DM as well as assessing baseline characteristics and outcomes. Second, clinical information about diagnosis or severity of illness (e.g., based on glycemic control) was not captured in the data. Therefore, the relationship between clinical measures such as glycemic control and basal insulin persistence in this study population remains unknown. Third, persistence patterns were assessed based on information regarding dispensed medications as opposed to actual observance of medications taken. In addition, pharmacy claims for patients aged ≥65 years may not capture all the prescription drug use because of the implementation of Medicare Part D in 2006, resulting in an underestimation of the degree of persistence. Fourth, as noted earlier, factors associated with treatment interruption and discontinuation were based on the information captured in the data and do not reflect physician or patient preference on changing course of therapy. Finally, the results are limited to commercially insured patients in the US and may not generalize to other populations (e.g., Medicare, Medicaid).

Conclusion

The study findings indicate that the vast majority of people initiating basal insulin either interrupt or discontinue treatment in the year after initiation, largely within the first 90 days, which is associated with increased medical resource use and costs during the two years after treatment initiation. In addition, we find that the majority of interrupters and discontinuers have similar persistence patterns in the subsequent year. Demographics, comorbidity profile, use of other antihyperglycemic medications, and medical resource use prior to treatment initiation are significantly associated with patterns of basal insulin use in the year after initiation. Further research is needed to understand additional reasons behind basal insulin persistence (e.g., self-reported or from physician’s perspective) and implications thereof, to help clinicians manage care for T2DM more effectively, resulting in potentially better outcomes for patients, providers, and payers.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Research funding provided by Eli Lilly and Company and Boehringer-Ingelheim to Analysis Group Inc.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

M.P.-N., R.D., D.C., and I.H. have disclosed that they are employees and stockholders of Eli Lilly and Company. S.K. has disclosed that she is an employee of Eli Lilly and company. U.D., J.I.I., N.Y.K., and H.G.B. have disclosed that they are employees of Analysis Group Inc. A.K.C. has disclosed that she was an employee of Analysis Group Inc. at the time of the study.

CMRO peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (56.9 KB)Acknowledgments

Previous presentation: Part of the findings from this study were presented at the 75th Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association, June 2015.

References

- American Diabetes Association. Data and Statistics about Diabetes. Available at: http://professional.diabetes.org/admin/UserFiles/0%20-%20Sean/Documents/Fast_Facts_3-2015.pdf. Accessed September 25, 2015

- American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2012. Diabetes Care 2013;36:1033-46

- Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: a patient-centered approach. Diabetes Care 2015;38:140-9

- Wright A, Burden ACF, Paisey RB, et al.; for the UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Sulfonylurea inadequacy: efficacy of addition of insulin over 6 years in patients with type 2 diabetes in the U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care 2002;25:330-6

- Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, et al. 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1577-89

- Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HA, et al. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. Br Med J 2000;321:405-12

- Wu N, Aagren M, Boulanger L, et al. Assessing achievement and maintenance of glycemic control by patients initiating basal insulin. Curr Med Res Opin 2012;28:1647-56

- Brunton S, Blonde L, Chava P, et al. Characteristics of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) on basal insulin who do not achieve glycemic goals. Oral presentation 112. 50th European Association for the Study of Diabetes Annual Meeting, 16–19 September 2014, Vienna, Austria. Available at http://www.easdvirtualmeeting.org/resources/19732. Accessed on September 25, 2015

- Liebl A, Jones S, Benroubi M, et al. Clinical outcomes after insulin initiation in patients with type 2 diabetes: 6-month data from the INSTIGATE observational study in five European countries. Curr Med Res Opin 2011;27:887-95

- Ascher-Svanum H, Lage MJ, Perez-Nieves M, et al. Early discontinuation and restart of insulin in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Ther 2014;5:225-42

- Baser O, Tangirala K, Wei W, Xie, L. Real-world outcomes of initiating insulin glargine-based treatment versus premixed analog insulins among US patients with type 2 diabetes failing oral antidiabetic drugs. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res 2013;5:497-505

- Wang L, Wei, W, Miao R, et al. Real-world outcomes of US employees with type 2 diabetes mellitus treated with insulin glargine or neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin: a comparative retrospective database study. BMC Open 2013;3:e002348

- Thayer S, Wei W, Buysman E, et al. The INITIATOR study: pilot data on real-world clinical and economic outcomes in US patients with type 2 diabetes initiating injectable therapy. Adv Ther 2013;30:1128-40

- Davis KM, Tangirala M, Meyers JL, Wei W. Real-world comparative outcomes of US type 2 diabetes patients initiating analog basal insulin therapy Curr Med Res Opin 2013;29:1083-91

- Cooke CE, Lee HY, Tong YP, Haines ST. Persistence with injectable antidiabetic agents in members with type 2 diabetes in a commercial managed care organization. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26:231-8

- Bonafede M, Kalsekar A, Pawaskar M, et al. A retrospective database analysis of insulin use patterns in insulin-naïve patients with type 2 diabetes initiating basal insulin or mixtures. Patient Prefer Adherence 2010;4:147-56

- Wei W, Pan C, Xie L, Baser O. Real-world insulin treatment persistence among patients with type 2 diabetes. Endocrine Practice 2014;20:52-61

- Perez-Nieves M, Jiang D, Eby E. Incidence, prevalence, and trend analysis of the use of insulin delivery systems in the United States (2005 to 2011). Curr Med Res Opin 2015;31:(5):891-9

- US Census Bureau. Regions and Division. Available at http://www.census.gov/econ/census/help/geography/regions_and_divisions.html. Accessed on January 5, 2016

- Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 2005;43:1130-9

- Imbens G. The role of the propensity score in estimating dose–response functions. Biometrika 2000;87:706-10