Abstract

Pharmacological treatments currently available to treat obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) rarely produce remission. This Editorial aims to encourage more targeted research based on the specific OCD symptoms patients primarily present with. Specific OCD symptoms have been associated with distinct clinical characteristics, aetiological hypotheses and treatment responses. Treatment studies should use these findings to develop more targeted pharmacotherapy for patients with OCD.

1. Introduction

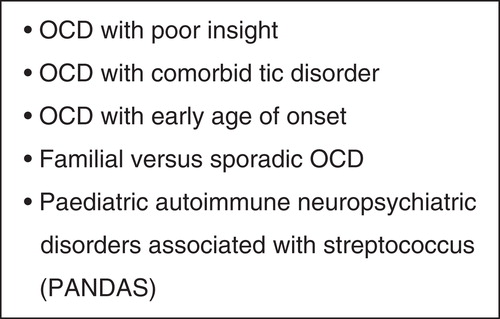

Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) is a heterogeneous condition in that it can present with many different symptoms. Although the presence of obsessions and compulsions is the key diagnostic element of OCD, sufferers of OCD can vary significantly in regards to their presenting symptoms Citation[1]. The OCD symptom dimensions that are commonly referred to in the literature are summarised in . OCD sufferers can also vary in regards to a number of other characteristics, and subtypes have been proposed on the basis of these characteristics, for example, whether OCD has an early or late age of onset. Potential subtypes of OCD are summarised in ; however, these subtypes are limited by their inconsistent definitions, overlapping features with OCD symptom dimensions and the small number of studies that have attempted to validate them. High-dose serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) can alleviate symptom severity for OCD sufferers; however, < 10% will achieve symptom remission, and a reduction in OCD symptom severity is said to occur in only 40 – 60% of those treated with high-dose SRIs Citation[2]. Additionally, the response to treatment with SRIs can take months and this is a longer period of time than what would be required for depression or other anxiety disorders. Hence, improved treatments for OCD are needed. The first-line treatment for OCD is either a high-dose SRI or the psychological approach of exposure and response prevention (ERP) Citation[3,4]. Due to the lack of psychologists skilled in the practice of ERP for OCD, the costs of psychological therapy and the distress associated with ERP (where sufferers are asked to expose themselves to the anxiety provoking stimulus), SRIs remain a popular treatment option for OCD sufferers. Pharmacological strategies offer hope for sufferers of OCD and future research needs to focus on greater and more rapid relief of symptoms in a wider range of sufferers.

Table 1. Common obsessive–compulsive disorder symptom dimensions referred to in the literature.

Attempts to improve the treatment of OCD using pharmacological agents that target different receptors within our central nervous system, for example, glutamatergic compounds, have been presented in the review article in this issue Citation[5]. These attempts are limited and have not provided the relief that OCD sufferers have been waiting for. It is likely that a different research strategy needs to be adopted and this may require a better understanding of the heterogeneity of OCD Citation[6].

2. OCD symptoms and pharmacotherapy

There have been several studies Citation[7-10] that have attempted to assess whether different OCD symptoms respond differently to pharmacological treatment. Hoarding symptoms have tended to have the poorest response to pharmacotherapy Citation[8,9]. The poor insight and schizotypy that can accompany hoarding have led some authors to conclude that antipsychotic augmentation of SRIs may be of benefit for hoarding symptoms Citation[11]. There are also several studies indicating that the neurobiological substrate for hoarding appears different to that of other OCD symptoms. Although hoarding symptoms often accompany OCD, new diagnostic conceptualisations of hoarding are suggesting that it may be a disorder in its own right (DSM5). Hence, there should be a focus on establishing new treatments for hoarding.

Some studies Citation[9] have also shown that contamination obsessions and cleaning compulsions have a poorer response to SRIs than other OCD symptoms. There has been recent research suggesting that the emotion of disgust, rather than anxiety, may play a significant role in the aetiology of contamination obsessions Citation[12]. In an attempt to reduce levels of disgust, some studies Citation[5] using the anti-emetic ondansetron off-label to augment SRI treatment have been conducted for contamination/cleaning symptoms.

Most studies Citation[7,8], indicate that symmetry/ordering symptoms do not show a differential response to treatment with SRIs, and yet symmetry/ordering symptoms are also accompanied by distinct characteristics. These include: not being classically ego-dystonic Citation[13], being accompanied by ‘just-right’ sensations Citation[14] and a higher co-occurrence of tics Citation[14]. Studies of antipsychotic augmentation of SRI treatment for OCD patients with comorbid tic disorder have shown mixed results with one study showing that antipsychotic augmentation was beneficial, while another failed to confirm this Citation[11,15].

Checking compulsions also appear not to have a differential response to treatment with SRIs Citation[8,9]. However, a systematic evaluation of treatment response as a function of the different obsessions occurring with checking has not been undertaken. Hence, treatment studies relating to sexual obsessions, religious obsessions, aggressive obsessions are needed.

3. Expert opinion

Current pharmacotherapy for sufferers of OCD can offer symptom reduction, but uncommonly leads to symptom remission. At this point in time, high-dose SRIs and ERP remain the mainstay of treatment of OCD, regardless of OCD symptom subtype. However, personal experience suggests that patients tend to respond differently to different SRIs and that SRIs should be changed within a few weeks should there be no response, even though the full potential of the SRI is unlikely to be realised for several months.

Current research is limited by a lack of novel treatments attempting to use advances that have been made in understanding the aetiology of specific OCD symptoms. The use of ondansetron off-label to alleviate the emotion of disgust that may be contributing to the formation of contamination obsessions and cleaning compulsions is a good example of a study that uses theories about aetiology of a specific OCD symptom to assess a targeted treatment.

In addition to working towards a better conceptualisation of OCD symptoms and their aetiology, more research is required to understand how SRIs reduce OCD symptoms. Pizarro M et al. Citation[5] correctly state that no studies in recent years have questioned what seems to be an undisputed clinical fact, that is, the efficacy of SRIs in the treatment of OCD. It would be useful if trials of pharmacotherapy could assess efficacy with more than the standard measures of symptom severity. Measures relating to the reduction of specific OCD symptoms may be useful to determine whether some OCD symptoms respond to treatment earlier than others and whether some OCD symptoms respond with lower doses of SRIs.

Recent advances in our understanding of the heterogeneity of OCD should be used to develop new treatments for patients suffering from OCD. This will lead to a re-evaluation of currently widely accepted practices and the way that we study treatment response in OCD.

Declaration of interest

V Brakoulias has received funding for research from the Nepean Medical Research Foundation, a competitive Pfizer Neuroscience grant and the University of Sydney. The author has no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Notes

Bibliography

- Brakoulias V, Starcevic V, Berle D, et al. Further support for five dimensions of obsessive-compulsive symptoms. J Nerv Ment Dis 2013;201:452-9

- Jenike MA, Rauch SL. Managing the patient with treatment-resistant obsessive compulsive disorder: Current strategies. J Clin Psychiatry 1994;55:11-14

- NICE. Obsessive-compulsive disorder: core interventions in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder and body dysmorphic disorder. Clinical Guideline 31. 2005. Available from: www.nice.org.uk/guidelines.aspx?o=guidelines.completed [Cited 5 January 2011]

- Koran L, Simpson H. Guideline watch (March 2013): practice guideline for the treatment of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder, in APA practice Guidelines. Am Psychiatric Assoc 2010

- Pizarro M, Fontenelle L, Paravidino D, et al. An updated review of antidepressants with marked serotonergic effects in obsessive–compulsive disorder. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2014;15(10):1391-401

- Heyman I, Mataix-Cols D, Fineberg N. Clinical Review: obsessive-compulsive disorder. BMJ 2006;333:424-9

- Erzegovesi S, Cavallini MC, Cavedini P, et al. Clinical predictors of drug response in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2001;21(5):488-92

- Mataix-Cols D, Rauch SL, Manzo PA, et al. Use of factor-analyzed symptom dimensions to predict outcome with serotonin reuptake inhibitors and placebo in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156(9):1409-16

- Stein DJ, Andersen EW, Overo KF. Response of symptom dimensions in obsessive-compulsive disorder to treatment with citalopram or placebo. Rev Bras Psiquiatr 2007;29(4):303-7

- Starcevic V, Brakoulias V. Symptom subtypes of obsessive-compulsive disorder: are they relevant for treatment? Aust NZJ Psychiatry 2008;42(8):651-61

- McDougle CJ, Goodman WK, Leckman JF, et al. Haloperidol addition in fluvoxamine-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study in patients with and without tics. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994;51(4):302-8

- Olatunji BO, Moretz MW, Wolitzky-Taylor MB, et al. Disgust vulnerability and symptoms of contamination-based OCD: descriptive tests of incremental specificity. Behav Ther 2010;41(4):475-90

- Eisen J, Greenberg BD, Mancebo M, et al. OCD Subtypes. American Psychiatric Association, Toronto CA; 2006

- Coles ME, Frost RO, Heimberg RG, et al. “Not just right experiences”: perfectionism, obsessive-compulsive features and general psychopathology. Behav Res Ther 2003;41(6):681-700

- McDougle CJ, Epperson CN, Pelton GH, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of risperidone addition in serotonin reuptake inhibitor-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000;57(8):794