Abstract

A record 4113 fatalities were reported in 2012 in a postmarketing surveillance of patients treated with deferasirox, despite warnings of life-threatening toxic side effects, and the need for regular monitoring and prophylactic measures. In an EMA report, the mortality rate was estimated at 11.7% and a warning was issued for increasing the dose from 30 to 40 mg/kg/day. In an earlier FDA report of 2474 individual fatality cases, it was revealed that deferasirox was used in many categories of patients. Among the fatal cases reported were many young individuals and about 500 patients with normal iron stores such as cancer, leukaemia, cardiovascular and neurological diseases. The iron-loaded patient categories included myelodysplasia, sickle cell disease, haemochromatosis and thalassaemia. The rate of fatalities and the number of patient categories involved suggest that there has been an indiscriminate and uncontrollable use of deferasirox. These findings raise major concerns on patient safety and question the role, practices and procedures adopted by pharmaceutical companies, regulatory authorities, physicians, etc. in the development of new drugs and their safety. The generic drugs deferiprone, deferoxamine and their combination offer a safer, less expensive and complete treatment of iron overload in thalassaemia and other iron loading conditions.

1. Introduction

The main iron-chelating drugs are the generic deferoxamine and deferiprone and the patented drug deferasirox, all of which are used for the treatment of thalassaemia and other iron loading conditions. The efficacy, toxicity and risk/benefit assessment of the use of the chelating drugs have been previously reviewed Citation[1-3].

The toxic side effects including the rate of mortality are different for each iron-chelating drug. A small number of fatal incidences have been reported since the introduction of deferoxamine in the 1960s, mainly in relation to mucormycosis and yersiniasis Citation[1,2,4]. Similarly, a few fatal agranulocytosis cases have also been reported with deferiprone, which has been widely used since 1995 Citation[1-3]. The highest rate of mortality is associated with deferasirox, which has been introduced since the end of 2005 and can cause renal, hepatic, gastrointestinal and bone marrow failure Citation[1-3,5].

In the developing countries, where most thalassaemia patients live, the treatment is inadequate because of the lack of facilities and unaffordable costs of treatment. In the EU and the US, the iron-chelating drugs are classified as orphan drugs, with more relaxed procedures for approval but with no strict control on the level of toxicity or pricing. The annual sales of chelating drugs are estimated at ∼ €1.5 billion, mainly because of the upsurge of use and high cost of deferasirox Citation[2,6]. Deferasirox is currently indicated for the treatment of transfused thalassaemia patients and non-transfusion-dependent thalassaemia patients, where deferoxamine therapy is contraindicated or inadequate Citation[5].

There are major concerns on patient safety in relation to the use of deferasirox and an urgent need for the introduction of regular monitoring and prophylactic measures Citation[1-3].

2. Record number of fatalities during the use of deferasirox

The fatality and toxicity data on deferasirox have been gathered from disclosures of postmarketing reports by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA), which are monitored by non-profit organisations associated with doctor and patient organisations interested in transparency and the safeguard of patients Citation[7-10].

The deferasirox fatalities have shown a steady increase over the last few years (). The number of deaths reported to FDA during 2009, which was monitored by the Institute for Safe Medication Practises has shown that deferasirox was the second ranking drug with 1320 fatalities (, column A) Citation[7]. The first-in-rank drug was rosiglitazone with 1354 and the third digoxin with 506 deaths. These findings were unexpected and should have alarmed the regulatory authorities since per patient population deferasirox should have been at the top of the table Citation[7]. It should be noted that rosiglitazone has already been withdrawn from clinical use.

Figure 1. Progressive increase in the number of reported fatalities of patients treated with deferasirox. Column A, represents the number of FDA reported fatalities in a report by the Institute for Safe Medication Practises in 2009 Citation[7]; Column B, of an EMA-related fatalities report at the end of 2009 Citation[8]; Column C, of an FDA-related solicitor's fatalities report of 2010 Citation[9]; Column D, of an FDA-related fatalities report at the end of 2012 by eHealthMe Citation[10].

![Figure 1. Progressive increase in the number of reported fatalities of patients treated with deferasirox. Column A, represents the number of FDA reported fatalities in a report by the Institute for Safe Medication Practises in 2009 Citation[7]; Column B, of an EMA-related fatalities report at the end of 2009 Citation[8]; Column C, of an FDA-related solicitor's fatalities report of 2010 Citation[9]; Column D, of an FDA-related fatalities report at the end of 2012 by eHealthMe Citation[10].](/cms/asset/5d1c1f5d-c112-42b0-b519-b9ec915a25d3/ieds_a_799664_f0001_b.jpg)

In a subsequent report by EMA in 2009, there were 1935 fatalities out of 16,514 patients (11.7%) (, column B) Citation[8]. These findings were based on a report by FDA related to 85% sales of deferasirox. EMA suggested that most of the reported deaths occurred in elderly patients with underlying myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) Citation[8]. A warning was issued that deferasirox's toxicity is likely to increase when the maximum recommended dose increases from 30 to 40 mg/kg/day Citation[3,8].

In 2010, FDA-based information on individual fatality cases has shown that deferasirox has been used in many categories of patients of variable age including many young individuals and that the deaths in elderly patients with underlying MDS were not a majority () Citation[9]. From a total of 2474 deaths, there were reports of about 700 MDS, 87 sickle cell disease, 77 haemochromatosis and 10 thalassaemia patients (, column C) Citation[9]. About 500 of the cases included cancer, cardiovascular, neurological and other categories of patients with normal iron store levels Citation[9]. The categories of diseases reported with fatalities suggest that there was an uncontrollable and indiscriminate use of deferasirox and also misinformation about its safety and the indications for use ().

Table 1. Categories of diseases and number of fatalities reported during treatment with deferasirox*.

In a 2012 study based on FDA and user community reports, 17,771 toxic side effects were reported including 4113 fatalities (, column D) Citation[10]. No fatalities were reported with deferoxamine or deferiprone users in the same period Citation[10].

The overall rate of fatalities and the indiscriminate use of deferasirox is alarming with regards to the safety for all the categories of patients involved. It would appear that many of the toxic side effects of deferasirox are irreversible and that no sufficient or effective safeguards have been implemented for monitoring and preventing the fatal and other serious toxic side effects.

3. Need for transparency and clarification of safety issues regarding the use of deferasirox

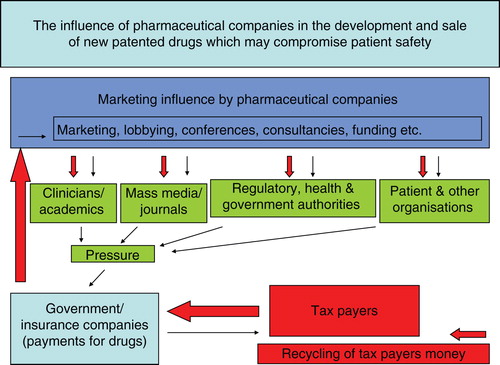

There are many questions on transparency and safety in relation to the use of deferasirox, which has one of the highest records of fatalities for new patented drugs. The medical literature report on the mortality and morbidity incidence including renal, hepatic and bone marrow failure and gastrointestinal haemorrhages during treatment with deferasirox is scarce Citation[7-10]. A major weak link in the transparency and safety issues is the lack of communication between the regulatory/health authorities and physicians. Unfortunately, this role is primarily undertaken by pharmaceutical companies which promote only positive aspects of the drug but downplay serious toxicities so that they can increase their sales. The promotion in most cases is through direct and private contact with the physicians, the sponsoring of participation in conferences which are supported/influenced by the pharmaceutical companies, the sponsoring of research and publications almost exclusively on positive results but not on toxicity, the provision of consultancies and medical writers for publication in journals, etc. () Citation[2]. Similar promotional incentives are provided to patient organisations, health authorities, universities, etc. ().

Figure 2. A theoretical model describing the marketing influence of pharmaceutical companies in relation to new patented drugs and its effect on public spending.

The driving force for the marketing promotion of deferasirox appears to be related to the ease of oral application, exclusive licence and monopoly on sales. The high cost of deferasirox (€80,000 per patient per year, at 40 mg/kg/day) is mainly associated with the marketing expenses and not the cost of preparation (€200 per patient per year) Citation[2,6]. In the case of deferasirox, the high income from sales (estimated at > €1 billion) overrun the pay off of any litigation damages associated with the fatalities and other serious toxicities.

The marketing procedures promoting the safety and efficacy of deferasirox were exaggerated to the extent that it has been indiscriminately prescribed for many categories of patients including non-iron loading conditions causing unnecessary fatalities () Citation[9]. These findings question the role of the regulatory authorities, where instead of taking appropriate action and installing strict safety procedures for minimising fatalities, further relaxation procedures and extension of use in other conditions were implemented, which are likely to increase further the rate of morbidity and mortality for patients treated with deferasirox Citation[2,3].

Similarly, there are no transparent and effective regulatory procedures addressing the risk/benefit assessment of the use of deferasirox versus the generic drugs. Less expensive, more effective and safer treatments are available for iron overload using deferoxamine, deferiprone and their combination Citation[11-15].

It is doubtful that present policies serve patient safety and is necessary that more safeguards and regulatory procedures are urgently introduced.

4. Expert opinion

The record number of fatalities reported for users of deferasirox is among the highest ever reported for any new patented drug per patient population. These unprecedented toxicity levels have not been previously observed with deferiprone and deferoxamine. Major questions on patient safety have been raised in relation to regulatory authority procedures, the marketing influence of pharmaceutical companies and the role of the prescribing physicians in the indiscriminate and uncontrollable use of deferasirox. The loopholes in regulatory authority procedures, the implementation of relaxation instead of restriction rules, the marketing influence of pharmaceutical companies, the lack of transparency and the insufficient publication of the toxicity incidence have compromised patient safety and resulted in a record number of fatalities during the use of deferasirox.

Deferasirox's fatality and serious toxicity rate is likely to increase in the next few years since the maximum recommended dose has recently increased from 30 to 40 mg/kg/day and at the same time no mandatory monitoring or prophylactic measures have been introduced or the indications for use restricted Citation[3].

Transparency in the pricing of deferasirox needs to be addressed in light of the selection criteria for drug treatments and also in the debate regarding health budgets and the reallocation of public resources.

Data on efficacy and safety suggest that deferasirox should not be recommended as a first-line treatment for thalassaemia and other categories of iron-loaded patients except for those who cannot tolerate deferoxamine, deferiprone and the deferiprone/deferoxamine combination Citation[2,11-15].

Selected deferiprone/deferoxamine combination protocols could reduce the iron load of thalassaemia patients to normal range levels, which could be maintained mostly using deferiprone monotherapy Citation[11]. In contrast to deferasirox, the use of deferiprone, deferoxamine and their combination offer a safer, less expensive and more effective treatment of iron overload, which appear to have transformed thalassaemia from a fatal to a chronic disease Citation[11-13].

Declaration of interest

This paper was supported by funds from the Postgraduate Research Institute (PRI) of Science, Technology, Environment and Medicine (a non-profit charitable organisation, Cyprus). G J Kontoghiorghes is supported by PRI.

Bibliography

- Kontoghiorghes GJ. Deferasirox: uncertain future following renal failure fatalities, agranulocytosis and other toxicities. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2007;6:235-9

- Kontoghiorghes GJ. Transparency and access to full information for the fatal or serious toxicity risks, low efficacy and high price of deferasirox, could increase the prospect of improved iron chelation therapy worldwide. Hemoglobin 2008;32:608-15

- Kontoghiorghes GJ. Introduction of higher doses of deferasirox: better efficacy but not effective iron removal from the heart and increased risks of serious toxicities. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2010;9:233-41

- Boelaert JR, Fenves AZ, Coburn JW. Deferoxamine therapy and mucormycosis in dialysis patients: report of an international registry. Am J Kidney Dis 1991;18:660-7

- Exjade (deferasirox) tablets for oral suspension. Highlights of prescribing information. Novartis Pharmaceutical Corp, USA (T2011-106); 2011. p. 1-16

- Cohen AR. Iron chelation therapy: you gotta have heart. Blood 2010;115:2333-4

- Anonymous. Fatal adverse drug events. ISMP Medicat Saf Alert 2010;15(12):1-3

- Pocock N. CHMP finalises review of deaths associated with deferasirox (Exjade®) in the US and updates to the SPC. Reference: October 2009 Plenary meeting monthly report Source: EMEA. 2009. Available from: http://www.nelm.nhs.uk

- Schwartz A. 2010.FDA reports. Exjade. 2474 reported reactions/deaths. Available from: http://www.fda-reports.com/exjade/reaction/death/page1.html

- Anonymous. eHealthMe - Real World Drug Outcomes. 2012. Available from: http://www.ehealthme.com/q/exjade-side-effects-drug-interactions

- Kolnagou A, Kleanthous M, Kontoghiorghes GJ. Reduction of body iron stores to normal range levels in thalassaemia by using a deferiprone/deferoxamine combination and their maintenance thereafter by deferiprone monotherapy. Eur J Haematol 2010;85:430-8

- Farmaki K, Tzoumari I, Pappa C, et al. Normalisation of total body iron load with very intensive combined chelation reverses cardiac and endocrine complications of thalassaemia major. Br J Haematol 2010;148:466-75

- Tefler P, Goen PG, Christou S, et al. Survival of medically treated thalassaemia patients in Cyprus. trends and risk factors over the period 1980 – 2004. Haematologica 2006;91:1187-92

- Angelucci E, Barosi G, Camaschella C, et al. Italian Society of Hematol practice guidelines for the management of iron overload in thalassemia major and related disorders. Haematologica 2008;93:741-52

- Meerpohl JJ, Antes G, Rücker G, et al. Deferasirox for managing iron overload in people with thalassaemia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;2:CD007476