Abstract

Recent high-profile failures in healthcare highlight the ongoing need for improvements in patient safety. Moreover, the fiscal challenge facing many health systems has brought the costs and economic efficiencies associated with improving quality (and safety) to bear. Currently, there is a lack of economic evidence underpinning resource allocation decisions in patient safety. Incident reporting systems are considered an important means of addressing these challenges by monitoring incident rates over time, identifying new threats to patient care and ultimately preventing repetition of costly adverse events. Uniquely, for more than a decade, the UK has been developing a National Reporting and Learning System to provide these functions for the English and Welsh health system(s), in addition to pre-existing local systems. The need to evaluate the impact of national incident reporting, and learning systems in terms of effectiveness and efficiency is argued and the methodological challenges that must be considered in an economic analysis are outlined.

In the wake of high-profile failures in healthcare delivery Citation[1], the need to implement technologies, processes and workforce skills that improve patient safety is high. It is only more recently that the question of the associated costs and economic efficiencies associated with these efforts has come to bear, driven by the fiscal challenge facing many health systems worldwide. Currently, policy makers lack a strong evidence base to decide how best to allocate resources to patient safety in order to maximise gains in population health or wealth. The efficient allocation of resources is a definitional component of high quality care (and safety) Citation[2]. For this reason, and as Meltzer wrote in his 2012 editorial, economic analyses in patient safety are (at present) a ‘neglected necessity’ Citation[3].

Incident reporting & learning systems in the UK

In light of the well-documented fiscal challenge facing the NHS Citation[4,5], the economic burden of poor quality care Citation[6] is one reason for allocating resources to develop national systems that counter this; however, despite years of growing experience, there is a dearth of evidence to support optimal decision making in this area, towards more efficient care.

The idea of reporting patient safety incidents in a systematised manner originated from high-risk industries where safety is paramount, such as aviation and nuclear power. Incident reporting systems (‘reporting systems’ hereafter) helped create high reliability organisationsFootnote 1 in these settings by closing the information loop effectively, something yet to be robustly demonstrated in healthcare Citation[7].

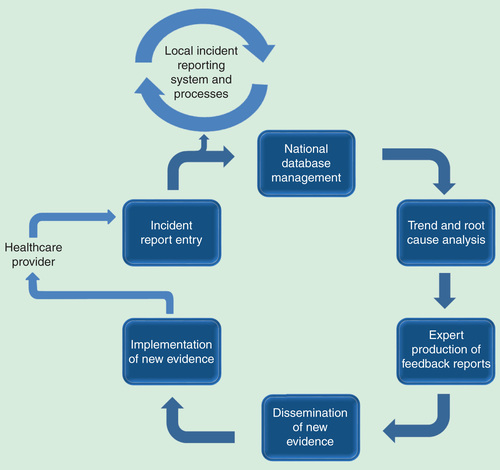

Figure 1. A conceptual view of national and local incident reporting and learning systems as information loops. Each input, process and output component represents an opportunity cost to society.

Nevertheless, national and local reporting systems are seen as an important means of improving the management of patient safety and encouraging a safety culture in healthcare; however, the lack of research on the amount of health system resources they consume and the utility they derive is a barrier to quality improvement. The National Reporting and Learning System (NRLS) was set up in the UK in 2002 as the first of its kind. The NRLS collects incident reports from healthcare providers across England and Wales and delivers learning in the form of alerts and guidelines (feedback reports) back to the NHS. This ameliorating action aims to prevent repetition of patient safety incidents, detect new threats to patient care and track reporting rates, the latter of which is a proxy for organisational risk and safety performance monitoring Citation[8]. More evidence is needed to inform the development and role of reporting systems in quality improvement.

The cost of building organisational memory

The collection, consolidation and analysis of incident reports, followed by the production of new information, and its full implementation has an unknown cost to health systems Citation[9]. The measurement of this is an important step towards understanding the utility of the NRLS. Our research group has started this extensive work taking a two-stage approach to derive centralised and decentralised direct costs. The methodological steps for this include identifying resources, measuring the intensity of resource use and valuing those resources. The centralised cost analysis is based on a human capital analysis of the NRLS operations group (now managed by an NHS trust), supplemented by the parliamentary funding records for the National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) from 2001 to 2012.Footnote 2 For the NPSA period, the average centralised NRLS costs were £18.2 million per year and for the post-NPSA period (since June 2012) the average annual costs are now approximately £1.1 million. The closure of the NPSA coincides with a significant reduction in annual expenditure on the NRLS, which is explained in part by the transition of the system from a start-up and development period into an operational phase.

There is an overall lack of costing evidence in patient safety due, in part, to the methodological difficulties of attributing value to resources employed. Capturing costs associated with producing feedback reports typifies this difficulty. The production of reports differs depending on the nature of the incident under investigation as resource intensity is higher in some areas due to the level of response required and attendant expert costs. There are a number of groups involved in the production of NRLS feedback, including quality assurance bodies, medical institutions and independent experts; the associated costs of these activities are not fully captured in the NPSA records but must also be included in the centralised cost analysis.

Using the same methodology, an estimation of the decentralised or frontline NHS staff costs is underway. This part of the economic evaluation aims to capture infrastructure and human capital costs of incident report entry and subsequent implementation of feedback reports.

Defining & measuring economic value

Presently, we define the output (production) function of the NRLS as the units of information or feedback that it produces over time. Feedback reports are published through the central alerting system (CAS) Citation[10], a web-based portal used by the NHS, and are classified as either patient safety alerts, which are high priority or guidelines, which are low priority. To characterise these, we searched the CAS and identified 180 feedback reports published between 2002 and 2012. The highest and lowest report outputs for these years are 44 and 1, and the majority of reports were guidelines (69%) rather than alerts (31%). The utility produced from these units should be defined as population health gains or monetised benefits, rather than simple output units. For this, researchers will have to grapple with a number of methodological challenges.

An evaluation method must establish causal inference between the NRLS operation and system-level impact(s) on outcomes using two potential observation periods in a time series analysis: the pre-post NRLS period as a whole and a more granular design that takes a pre-post feedback report publication approach to which appropriate quasi-experimental methods are applied.

The impact of specific feedback reports is of interest to determine what reports the NRLS should produce in future. For this, one hypothesis we consider is that the benefits from alerts and guidelines are proportional to the degree of their implementation; there is particularly limited evidence on the latter. A search of the literature finds one publication, which describes good compliance with feedback report implementation Citation[11], whereas two publications report mixed awareness and implementation effort across NHS organisational levels Citation[12,13]. The equivocal evidence on implementation steers the choice of study design, as we now discuss.

Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series data may be the appropriate policy evaluation design. The approach lends to the visualisation and analysis of trend and level changes in the response variable by the time unit (month or year) observed Citation[14]. These are important components that should improve our understanding of the ‘roll-in period’ and other lags that follow feedback report publication. Second, a segmented regression analysis design allows selection of a comparator group using separate, but related outcome measures Citation[14] that would not be expected to change after feedback report publication. This feature allows analysts to estimate the intervention effect in the absence of a control cohort. An alternative method, for example, a difference-in-difference design, is less supportive of this because the estimator is calculated using differences between the same outcome measure for the treatment and control groups Citation[15]. Also, the use of point estimates between segments in difference-in-difference means that the analyst must be confident in the segments defined in the model ex ante, which is why it is attractive in directive-policy evaluation; for example, see Cooper et al. Citation[16]. Without this, segmented regression analysis is a more appropriate study design.

Next, it is important to acknowledge that an implementation variable is unlikely to fully explain utility impact and another explanatory variable that addresses information quality is needed. This is because evidence from local systems suggests that incident reports do not accurately reflect the clinical events they pertain to Citation[17,18]. To try to tackle these methodological issues, criteria have been developed for the selection of feedback reports for analysis based on safety priority and pathological groupings that are feasible for analysis in administrative datasets. We propose three broad priority categories of feedback that researchers should explore: medication, surgical and never events. Pathological groupings and related outcomes of interest are defined as a subset of these.

Researchers must also consider the utility derived from mitigated errors that are not measured in most routine administrative datasets. This issue is beyond the scope of this piece, partly because methods for assessing these are immature and warrant more detailed discussion.

In summary, there are a number of limitations to the cost analysis research described here and future research must consider the methodological issues we have outlined. The three immediate areas of focus are the lack of frontline and expert group resource use in the cost analysis, poor evidence about the degree and speed of implementation of feedback reports and the lack of outcome/utility measurement. The need to expedite this research to inform near-future spending is high given the financial pressure facing the NHS. We believe that an understanding of the potential contribution of a national incident reporting and learning system for healthcare quality improvement is of interest to most Western health systems.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This work was funded by healthcare quality improvement research grants awarded to the Department of Surgery and Cancer at Imperial College London. These include an NRLS research and development grant from NHS England. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilised in the production of this manuscript.

Notes

1High reliability organisations are defined as those that operate in hazardous settings with reliability and safety.

2Following advice from a former NPSA executive, 80% of NPSA expenditure is assumed to be NRLS development and operational costs.

References

- Francis R . Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Enquiry. HC 947 Stationery Office; London: 2013

- Donabedian A . The seven pillars of quality. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1990;114(11):1115-18

- Meltzer D . Economic analysis in patient safety: a neglected necessity. BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21(6):443-5

- HM Treasury . Public expenditure statistical analyses 2013. CM 8663 Stationery Office; London: 2013

- Roberts A , Marshall L , Charlesworth A . A decade of Austerity? The funding pressures facing the NHS from 2010/11 to 2021/22. Nuffield Trust; London: 2012

- Øvretveit J . Does improving quality of care save money? A review of evidence of which improvements to quality reduce costs to health service providers. The Health Foundation; London: 2009

- Mahajan R . Critical incident reporting and learning. Br J Anaesth 2010;105910:69-75

- Hutchinson A , Young TA , Cooper KL , et al. Trends in healthcare incident reporting and relationship to safety and quality data in acute hospitals: results from the national reporting and learning system. Qual Saf Health Care 2009;18(1):5-10

- Corbett-Nolan A , Hazan J . Bullivant. Cost savings in healthcare organisations: the contribution of patient safety. A guide for boards and commissioners. The Good Governance Institute; Sedlescombe: 2010

- The Central Alerting System . Available from: www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/resources/type/data-reports/ [Last accessed 15 November 2014]

- Lankshear A , Sheldon T , Lowson K , et al. Evaluation of the implementation of the alert issued by the UK National Patient Safety Agency on the storage and handling of potassium chloride concentrate solution. Qual Saf Health Care 2005;14:196-201

- Lankshear A , Lowson K , Weingart SN . An assessment of the quality and impact of NPSA medication safety outputs issued to the NHS in England and Wales. BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20(4):360-5

- Lankshear A , Lowson K , Harden J , et al. Making patients safer: nurses’ responses to patient safety alerts. J Adv Nurs 2008;63(6):567-75

- Wagner AK , Soumerai SB , Zhang F , et al. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther 2002;27:299-309

- Stuart EA , Huskamp HA , Duckworth D , et al. Using propensity scores in difference-in-differences models to estimate the effects of a policy change. Health Ser Outcomes Res Method 2014;14:166-82

- Cooper Z , Gibbons S , Jones S , et al. Does hospital competition save lives? Evidence from the English NHS patient choice reforms. Econ J 2011;121(554):F228-60

- Christiaans-Dingelhoff I , Smits M , Zwaan L , et al. To what extent are adverse events found in patient records reported by patients and healthcare professionals via complaints, claims and incident reports? BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11(1):49

- Sari A , Sheldon TA , Cracknell A , et al. Sensitivity of routine system for reporting patient safety incidents in an NHS hospital: retrospective patient case note review. BMJ 2007;334(7584):79