A recent Google™ search of the keyword ‘genomics’ produced approximately 107 million results. A more refined PubMed search using this keyword revealed 15,845 publications since 1988. Needless to say, I was unable to trace the origin of the word genomics in preparation for this editorial. However, it is thought that the word genome may have been formed in reference to the word chromosome Citation[101].

It was Marc Wilkins (University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia) who in 1994 coined the word ‘proteomics’ Citation[1]. This would soon be followed by ‘transcriptomics’, ‘spliceomics’ and ‘metabolomics’ and a rash of new ‘-omics’. The current trend is for researchers to create a vernacular specific to their field by suffixing keywords, thus creating a new and distinct discipline. I am also guilty of this, having once referred to a study of intestinal flora as ‘bowelomics’.

The suffix ‘-ome’ is thought to derive from the Latin prefix ‘omni-’, meaning total or complete. Thus, ‘-omes’ are intended to be a comprehensive description of all of the relevant components, both known and unknown, in a particular biomolecular subset. For example, the ‘metallome’ refers the total of all metal and metalloid species in an organism. The proposed ‘foldomics’ Citation[2], which examines protein folding, seems to depart from this convention. The oldest biological usage of ‘-ome’ is the term ‘biome’, coined in 1916 to describe the relationship between organisms and their environment. In a recent Scientific American article, Gary Styx commented, “Perhaps all things biological will be classified… leading to some hypothetical metadiscipline called biomics” Citation[3].

Suffixing a term with ‘-omics’ to create a new word is known as neologism. Wikipedia defines neologism as a word, term or phrase that has recently been created Citation[101]. Quite amusingly, in the field of psychology, neologism is a term used to describe the creation of words that have meaning only to the person who creates them, an acceptable behavior in children, but a condition symptomatic of altered thought processes in adults Citation[102]. By the way, the word ‘comic’ is not a neologism.

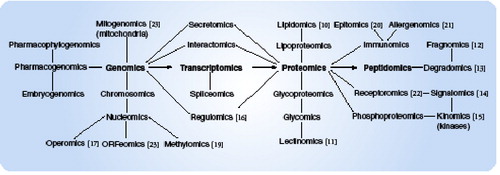

Thankfully, someone has undertaken the task of compiling the growing list of -omics. Authored by Mary Chitty, the ‘-Ome and -Omics Glossary: Evolution of Emerging Technologies’ is available online from Cambridge Healthtech Institute (MA, USA) Citation[103]. Listed in this alphabetized compilation are 194 entries of -omes and their related –omics. attempts to organize 31 of these.

Consider the ‘unknome’, which describes the large proportion of genes for which there is currently no functional information Citation[4]. Then there is ‘functomics’, which I first thought might be in tribute to Bootsy Collins, but turns out to be another phrase for ‘functional genomics’ Citation[5].

Not included in the current glossary is ‘albuminomics’, an area of research focusing on the interaction of plasma proteins with albumin and the biological significance of such interactions Citation[6]. It was recognized very early on that the subliminal layers of the plasma proteome could only be revealed following the immunodepletion of high-abundance proteins such as albumin and immunoglobulin. However, fraction revealed a host of proteins that were unexpectedly associated with albumin and raised the queNSstion, ‘Are we throwing away the baby with the wash water?’

More recently, Alexander Lazarev (Pressure BioSciences, MA, USA) introduced the concept of ‘cellular debriomics’ at the Cambridge Healthtech Institute 6th Annual Proteomics Sample Preparation Summit Citation[7]. He was referring to the insoluble cellular debris that is typically removed centrifugally and often excluded from the analysis.

Frank Witzmann once wrote, “There’s no place like -ome” Citation[8]. My personal favorite comes from Target Discovery’s (CA, USA) company slogan, ‘From Omics into Knowmics’ Citation[9].

In titling this editorial, I resisted the obvious pun “I’m an -Omics, Urinomics” in reference to AJ Rabelink’s (Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum, The Netherlands) term for urine analysis Citation[104].

References

- Wilkins MR, Pasquali C, Appel RD et al. From proteins to proteomes: large scale protein identification by two-dimensional electrophoresis and amino acid analysis. Biotechnology14, 61–65 (1996).

- Vidal MA. Biological atlas of functional maps. Cell104, 333–339 (2001).

- Styx G. Parsing Cells. Scientific American281, 35–36 (1999).

- Greenbaum Luscombe NM, Jansen R, Qian J, Gerstein M. Interrelating different types of genomic data, from proteome to secretome: ‘oming in on function. Genome Res.11, 1484–1502 (2001).

- Attur MG Dave MN, Tsunoyama K et al. A systems biology approach to bioinformatics and functional genomics in complex human diseases. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol.4, 129–146 (2002).

- Tam SW, Huang L, Hinerfeld D et al. Novel plasma separation using multiple avian IgY antibodies for proteomics analysis. In: Separation Methods in Proteomics. CRC Group, Taylor and Francis, FA, USA. 41–62 (2005).

- Lazarev A. Pressure cycling technology: a new paradigm in sample preparation for genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics. CHI Sixth Annual Proteomics Sample Preparation Summit. Boston, MA, USA, April 24–25 (2006).

- Witzmann F. There’s no place like ’ome. Brief. Funct. Genomic. Proteomic.1, 116–118 (2002).

- Schneider LV. Knowmics: affinity-enrichment mass spectrometry with mass defect tags for biomarker validation. CHI Sixth Annual Proteomics Sample Preparation Summit. Boston, MA, USA, April 24–25 (2006).

- Han X, Gross RW. Global analyses of cellular lipidomes directly from crude extracts of biological samples by ESI mass spectrometry: a bridge to lipidomics. J. Lipid Res.44, 1071–1079 (2003).

- Gabius HJ, Andre S, Kaltner H, Siebert HC. The sugar code: functional lectinomics. Biochem. Biophys. Acta.1572, 165–177 (2002).

- Zartler ER, Shapiro MJ. Fragonomics: fragment-based drug discovery. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol.9, 366–370 (2005).

- Lopez-Otin C, Overall CM. Protease degradomics: a new challenge for proteomics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.3, 509–519 (2002).

- Reddy AS. Calcium: silver bullet in signaling. Plant Sci.160, 381–404 (2001).

- Johnson SA, Hunter T. Kinomics: methods for deciphering the kinome. Nat. Methods2, 17–25 (2005).

- Werner T. Proteomics and regulomics: the yin and yang of functional genomics.Mass Spectrom. Rev.23, 25–33 (2004).

- Hanash SM. Operomics: molecular analysis of tissues from DNA to RNA to protein. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med.38, 805–813 (2000).

- Reboul Vaglio P, Tzellas N et al. Open-reading-frame sequence tags (OSTs) support the existence of at least 17,300 genes in C. elegans. Nat. Genet.27, 227–228 (2001).

- Costello J, Plass C. Methylation matters. J. Med. Genet.38, 285–303 (2001).

- Zijlstra A, Testa JE, Quigley JP. Targeting the proteome/epitome, implementation of subtractive immunization. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.303, 733–744 (2003).

- Yagami T, Haishima Y, Tsuchiya T, Tomitaka-Yagami A, Kano H, Matsunaga K. Proteomic analysis of putative latex allergens. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol.135, 3–11 (2004).

- O’Connor KA, Roth BL. Screening the receptorome for plant-based psychoactive compounds. Life Sci.78, 506–511 (2005).

- Pereira SL, Baker AJ. A mitogenomics timescale for birds detects variable phylogenetic rates of molecular evolution and refutes the standard molecular clock. Mol. Biol. Evol. (2006) (In press).

Websites

- www.answers.com/topic/omics

- www.answers.com/topic/neologism

- www.genomicglossaries.com

- www.lumc.nl/1090/Programma's%20LUMC%202006/Nephrology%2019.1–19.2. html