Abstract

Adherence to medication in patients with rheumatoid arthritis is low, varying from 30 to 80%. Improving adherence to therapy could therefore dramatically improve the efficacy of drug therapy. Although indicators for suboptimal adherence can be useful to identify nonadherent patients, and could function as targets for adherence-improving interventions, no indicators are yet found to be consistently and strongly related to nonadherence. Despite this, nonadherence behavior could conceptually be categorized into two subtypes: unintentional (due to forgetfulness, regimen complexity or physical problems) and intentional (based on the patient’s decision to take no/less medication). In case of intentional nonadherence, patients seem to make a benefit–risk analysis weighing the perceived risks of the treatment against the perceived benefits. This weighing process may be influenced by the patient’s beliefs about medication, the patient’s self-efficacy and the patient’s knowledge of the disease. This implicates that besides tackling practical barriers, clinicians should be sensitive to patient’s personal beliefs that may impact medication adherence.

Medscape: Continuing Medical Education Online

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education through the joint sponsorship of Medscape, LLC and Expert Reviews Ltd. Medscape, LLC is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Medscape, LLC designates this Journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

All other clinicians completing this activity will be issued a certificate of participation. To participate in this journal CME activity: (1) review the learning objectives and author disclosures; (2) study the education content; (3) take the post-test with a 70% minimum passing score and complete the evaluation at http://www.medscape.org/journal/expertimmunology; (4) view/print certificate.

Release date: 11 May 2012; Expiration date: 11 May 2013

Learning objectives

Upon completion of this activity, participants should be able to:

• Define appropriate terms for nonadherence to treatment and the prevalence of nonadherence in rheumatoid arthritis

• Evaluate means to measure adherence to treatment

• Distinguish risk factors for nonadherence to treatment

• Analyze means to improve adherence to treatment

Financial & competing interests disclosure

EDITOR

Elisa Manzotti,Publisher, Future Science Group, London, UK

Disclosure:Elisa Manzotti has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

CME AUTHOR

Charles P Vega, MD,Health Sciences Clinical Professor; Residency Director, Department of Family Medicine, University of California, Irvine, CA, USA

Disclosure:Charles P Vega, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

AUTHORS

Bart JF van den Bemt, PharmD, PhD,Department of Pharmacy, Sint Maartenskliniek, Nijmegen, The Netherlands

Disclosure:Bart JF van den Bemt, PharmD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Hanneke E Zwikker, MSc,Department of Rheumatology, Sint Maartenskliniek, Nijmegen, The Netherlands

Disclosure:Hanneke E Zwikker, MSc, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Cornelia HM van den Ende, PhD,Department of Rheumatology, Sint Maartenskliniek, Nijmegen, The Netherlands

Disclosure:Cornelia HM van den Ende, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

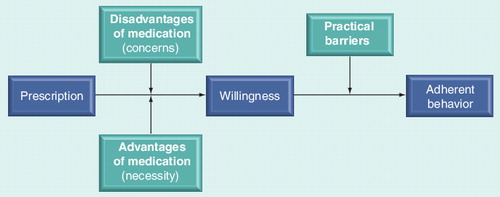

Intentional due to an imbalance between perceived benefits and concerns and unintentional due to practical barriers. During this discussion, the patient’s expertise and beliefs are fully valued.

The prescription of a medicine is one of the most common interventions in the healthcare system. However, the full benefit of pharmacological interventions can only be achieved if patients follow drug regimens closely. Adherence is, however, low in chronic medical conditions: approximately 50% of all people with chronic medical conditions do not adhere to their prescribed medication regimens Citation[1,2]. The implications of nonadherence are far reaching, as nonadherence may severely compromise the effectiveness of treatment and increase healthcare costs; for example, the cost of nonadherence in the USA has been estimated to reach US$100 billion annually Citation[3]. The reduction of nonadherence is therefore thought likely to have a greater effect in health than further improvements in traditional biomedical treatment Citation[4].

Medication nonadherence has negative consequences on the pharmacological treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), as disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) reduce disease activity and radiological progression and improve long-term functional outcome in patients with RA Citation[5]. Nonadherence is associated with disease flares and increased disability, for example Citation[6,7]. Despite this, adherence rates to prescribed medicine regimes in people with RA are low, varying from 30 to 80% Citation[7–22]. Improving adherence to therapy could therefore dramatically improve the efficacy of medical treatments and reduce costs associated with RA.

The purpose of this critical narrative appraisal of the literature is to give a broad overview of the existing literature on medication nonadherence and adherence to disease-modifying drugs in RA, by addressing adherence terminology, measuring nonadherence, the extent of the problem and risk factors for nonadherence, and by providing a short overview of interventions to improve medication adherence among people with RA. Available studies published until July 2011 on medication adherence in RA were searched for using an electronic literature search in PubMed. The search strategy is described in .

Adherence terminology: adherence, compliance & concordance

The terminology used in the area of medicine-taking reflects the changing understanding of medicine-taking behavior and the changing relationships between healthcare professionals and patients. In the medical literature of the 1950s, the term ‘compliance’ was used. This term, strongly led by a physician-based approach, was defined as the extent to which patient’s behavior coincides with medical advice Citation[23]. However, the word compliance became quickly unpopular for its judgmental overtones. Therefore, the term ‘adherence’ was introduced as an alternative to compliance. It comes closer to describing and emphasizing patient and clinician collaboration in decisions, rather than conveying the idea of obedience to a medical prescription Citation[24–26]. ‘Medication adherence’ can be defined as the extent to which a patient’s behavior, with respect to taking medication, corresponds with agreed recommendations from a healthcare provider Citation[101].

Medication adherence can be divided into three major components: persistence (defined as the length of time a patient fills his/her prescriptions); initiation adherence (does the patient start with the indented pharmacotherapy); and execution adherence (the comparison between the prescribed drug dosing regimen and the real patient’s drug-taking behavior). Execution adherence includes dose omissions (missed doses) and the so-called ‘drug holidays’ (3 or more days without drug intake).

In the mid 1990s, the concept of ‘concordance’ was born. The term ‘concordance’ relates to a process of the consultation in which prescribing is based on partnership. In this process, healthcare professionals recognize the primacy of the patient’s decision about taking the recommended medication, and the patient’s expertise and beliefs are fully valued. The term ‘concordance’ overtly recognizes that for optimal medication use, the patient’s opinion on medication should be taken into account and discussed throughout the therapy. This discussion will help to foster a patient–physician relationship in which the patient is able to communicate as a partner in the selection of treatment and the subsequent review of its effect. Therefore, compliance focuses on the behavior of one person (the patient), whereas concordance requires the participation of at least two people.

Measuring nonadherence

The validity of adherence assessment is based on the method of measurement. The minimum requirements of a gold standard for adherence measurement include:

• Validity: proving ingestion of the medication and giving a detailed overview about timing and ingestion;

• Reliability and sensitivity to change: stable results under stable adherence and differential results under variable adherence;

• Feasibility: the patient should not be aware of adherence measurement and should not be able to censor the result.

Although it is ethically desirable that patients know that his/her medication use is being followed, the consciousness of being monitored may increase a patient’s adherence. Moreover, the assessment should be easy to use and the method should be noninvasive. Unfortunately, a single instrument fulfilling these properties is currently unavailable Citation[27]. Despite the absence of a gold standard, adherence can be measured in a variety of ways, as depicted in Citation[9,10,28,29].

Subjective measurement

The simplest assessment of medication adherence is frequently used, and involves asking the patient whether he or she is taking the medications as prescribed. Although patient self-report may be 100% specific for being nonadherent, this method is relatively insensitive for the detection of nonadherence (which is confirmed in several studies showing that the answers of the patient are not always accurate). In fact, patients claiming to be adherent may under-report their nonadherence to avoid caregiver disapproval Citation[30]. Furthermore, self-report is time-dependent, since patients have the best recall for adherence in the last 24-h period.

Studies have consistently shown that third-party assessments (e.g., assessment by healthcare providers) are unreliable and tend to overestimate patient adherence Citation[30]. Physician’s estimate of patient’s adherence correlated poorly with objective pill counts Citation[31]. In more detail, physicians seem to detect good adherence well (specificity ∼90%), but were not good at predicting poor or partial adherence Citation[32].

Direct objective measurement

Direct methods prove directly that the medication has been taken by the patient. Examples of direct methods include direct observation and measurement of serum drug/metabolite levels or biological markers. Although no method is 100% reliable, direct measurements have low bias, although these methods may be expensive and inconvenient for patients.

Furthermore, the use of biological markers only reflects short-term adherence, and can overestimate patients’ long-term adherence due to the tooth-brush effect/white coat adherence. This phenomenon takes its name from the fact that dentists often see patients beginning to brush their teeth only a few days before the appointment. This can also be the case for drug taking, implicating that only drug/metabolites with long elimination half-lives are fair predictors for nonadherence. Interindividual differences in drug absorption and metabolism can also lead to inaccurate conclusions regarding medication adherence.

Indirect measurement

Indirect methods are the most common approach to measuring medication adherence. Commonly used indirect measures include: pharmacy refills; electronic monitoring; tablet counts; and questionnaires.

Pharmacy refills

Pharmacy refills provide a convenient, noninvasive, objective and inexpensive method for estimating medication adherence and persistence. Calculation of a patient’s refill adherence is especially suited for large populations of (chronic) medication users. However, the extent of adherence obtained from pharmacy refill data does not provide the patient’s medication consumption information, but rather provides the acquisition of the medication. Pharmacy refill data are therefore especially specific for identifying nonadherent patients Citation[33]. However, a number of different measures and definitions of adherence and persistence have been reported in the published literature. The appropriateness and choice of the specific measure employed should be determined by the overall goals of the study, as well as the relative advantages and limitations of the measures. A commonly used method is the medication possession ratio, often defined as the proportion of days supply obtained during a specified time period or over a period of refill intervals. However, it is important to notice that various methods of calculation of the medication possession ratio exist. Therefore, it is important to evaluate how the medication possession ratio was calculated when interpreting literature regarding patient adherence Citation[34].

Electronic monitoring devices

Electronic monitoring devices, such as the Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS) can be used to provide accurate and detailed information on medication-taking behavior Citation[35,36]. These devices compile the dosing histories of patients’ prescribed medication, registering the number of pills missed, as well as deviations from the dosing schedule. The availability and costs of MEMS devices could limit the feasibility of its use Citation[28,37,38]. Another disadvantage of electronic monitoring devices is the fact that an electronic device may increase the patient’s awareness about the fact that his/her adherence will be monitored. Although the boxes can be opened without medication being taken, MEMS devices have been shown to have superior sensitivity compared with other methods for the assessment of medication adherence.

Tablet counts

Tablet counts are frequently used in clinical trials and adherence research, but are notoriously unreliable and usually provide overestimates Citation[17,27]. Although using tablet counts offers advantages such as low costs, and relatively simple data collection and calculation, the accuracy of the assessment relies on the patient’s willingness to return unused medication Citation[39]. As a consequence, adherence may be overestimated, as patients can manipulate the tablet count by dumping the medication prior to the scheduled visits, leading to an overestimation of adherence. Furthermore, the reliability of the pill count is also dependent on the correct number of drugs being dispensed and counted.

Questionnaires

Although a number of self-report medication adherence questionnaires have been described in the literature, no gold standard questionnaire for the assessment of nonadherence and adherence in RA exists. Three adherence questionnaires are most widely used in RA: the Morisky questionnaire Citation[40]; the Medication Adherence Report Scale (MARS) Citation[41]; and the Compliance Questionnaire on Rheumatology Citation[42,43]. The Morisky scale is a commonly used questionnaire that consists of four questions on reasons for nonadherence, which are answered with a yes/no response. The measure has been found to have adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.61), a good sensitivity (0.81) and moderate specificity (0.44 ) when validated to non-RA clinical parameters such as blood pressure Citation[40,44]. The Morinsky scale is not yet validated in RA. The MARS has been used in a variety of patients (e.g., patients with asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, high cholesterol, RA and diabetes) Citation[41]. Four of the five items in the MARS are related to intentional nonadherence, such as the tendency to avoid, forget, adjust and stop taking medication, whereas one MARS item focuses on forgetting medication Citation[16,45]. However, both the Morisky scale and the MARS did not perform well compared with an electronic MEMS in transplant recipients taking oral steroids and immunosuppressants Citation[45].

Currently, there is only one rheumatology-specific adherence measure: the 19-item Compliance Questionnaire on Rheumatology. This questionnaire has been validated in patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases against a MEMS device Citation[13]. The 19-item Compliance Questionnaire on Rheumatology compares well with electronic monitoring over 6 months, with a sensitivity of 0.98, a specificity of 0.67 and an estimated κ of 0.78 to detect nonadherence Citation[13,42,43].

In conclusion, although a wide variety of methods have been used to assess nonadherence and adherence, a gold standard for adherence assessment is lacking. Although objective methods (e.g., blood or urine samples, pharmacy refill data, electronic pill monitoring or pill counts) are considered to be more reliable than subjective methods, they are in general more expensive and more complicated than subjective methods. Urine and serum samples are constrained by interindividual variations, whereas pill counts and electronic devices assume that patients really take their medication when they pick up the drug in the pharmacy and/or open the bottle of pills. Although subjective measures are cheap and relatively easy to use, the psychometric properties of these instruments are often poor; patient self-reported adherence is often poorly associated with adherence rates assessed with a MEMS device and pill count Citation[46–49]. It has been suggested that adherence may be underestimated by MEMS and overestimated by patient self-report and pill count Citation[49].

Extent of the problem: adherence to traditional & biological DMARDs

Studies reporting adherence rates on both traditional and biological DMARDs are listed in . Despite the varied extent of nonadherence found in these studies, they all confirm that adherence in RA is still suboptimal. Nine studies exclusively targeted nonadherence to DMARDs. These studies were published between 1988 and 2010, with sample sizes ranging from 26 to 14,586. The authors used several methods for capturing DMARD medication adherence, including subjective (patient interview and physician’s estimation), direct (chemical markers) and indirect (MEMS, refill data and pill count questionnaires) methods. Estimates of the extent to which patients adhere to DMARD therapy varied between 22 (underuse) and 107% (overuse). This variation relates to differences in the study groups, the duration of follow-up (1 day–1 year), the type of drugs included, the definition of adherence (e.g., used cutoff points), the duration of the disease (in order to separate initiation and execution adherence) and methods of assessment. As seen in , adherence rates in studies using MEMS devices ranged from 72 to 107%, adherence rates obtained with refill dates ranged from 22 to 73% and with self report from 50 to 99%. Besides studies only focusing on DMARDs, several studies included both NSAID and DMARD users. These studies may overestimate the extent of adherence, as adherence to pain relievers (with an almost immediate pain relief) could theoretically be higher, compared with slow-acting drugs (with often a delayed onset to retard disease progression).

An important point to consider is that medication adherence is a dynamic feature that is not stable over time Citation[41,50,51]. This is confirmed in two longitudinal studies in this population suggesting that 12–24% of the patients with RA are consistently nonadherent, whereas only 30–35% of the patients are consistently adherent. Furthermore, in contrast to cross-sectional studies, it is important to notice that longitudinal studies including patients from the start of therapy will also measure initiation nonadherence. Recognition of the dynamic nature of medication adherence (both during initiation and execution of the pharmacotherapy) is therefore important when considering ways in which poor medication-taking behavior could be improved.

Risk factors for nonadherence

Knowledge of factors associated with medication adherence in RA could help healthcare professionals to identify patients who would benefit from an intervention in this regard, and could provide possible targets for treatment of nonadherence. Studies examining associates to adherence with DMARDs in RA are listed in . According to the WHO, factors associated with nonadherence can be divided into five domains Citation[101]: socioeconomic factors; healthcare system factors; condition-related factors; therapy-related factors; and patient-related factors.

Socioeconomic factors

In RA, many sociodemographic factors have been studied as potential risk factors for nonadherence. Factors such as age, gender, education, tobacco use, social–economic status, living situation, marital status and presence of children were not unequivocally related to adherence. Age, for example, is not consistently associated with medication nonadherence. While some investigators have found older patients to have better adherence, others have shown younger patients to be more successful adherers Citation[6,7,15,18,19,52,53]. However, the association between age and nonadherence and adherence may also be influenced by confounding factors such as multiple comorbidities and complex medical regimens (which are both often associated with an increased age). Although studies in other conditions suggested that ethnical/cultural aspects could predict nonadherence, evidence in RA is lacking. Only one study demonstrated that RA and systemic lupus erythematosus patients of south Asian origin have higher levels of concerns regarding DMARDs and are generally more worried about prescribed medicines. Concerns about medication may have an impact on adherence in this group of patients Citation[54].

Healthcare system factors

Whereas a good patient–provider relationship seems to improve adherence Citation[7,52,55], poorly developed health services with inadequate or nonexistent reimbursement by health insurance plans negatively affect adherence Citation[14].

Condition-related factors

A number of condition-related risk factors have been studied, such as disease activity, erythrocyte sedimentation rates, morning stiffness, overall (perceived) health, functioning, disease duration and quality of life. However, none of these factors were consistently related to nonadherence. Only perceived effect was poorly associated with nonadherence and adherence. In other chronic diseases, however, comorbidities such as depression Citation[56] (in diabetes or HIV/AIDS), and drug and alcohol abuse are important modifiers of adherence behavior.

Therapy-related factors

Although there are many therapy-related factors that could potentially affect adherence, none of these factors (class of medication, drug load, the immediacy of beneficial effects and side effects) were adequate predictors for nonadherence in RA Citation[11,20,22,57]. Despite this, a review of studies in non-RA patients confirmed that the prescribed number of doses per day and the complexity of the regimen was inversely related to compliance. Simpler, less frequent dosing regimens resulted in better compliance across a variety of therapeutic classes Citation[58].

Patient-related factors

Patients seem to adhere better when the treatment regimen makes sense to them: when the treatment seems effective, when the benefits seem to exceed the risks/costs (both financial, emotional and physical), and when they feel they have the ability to succeed at the regimen. Therefore, patient knowledge, self-efficacy, and beliefs about the disease and its treatment indeed seem to influence adherence behavior Citation[7,11,15,18,20,52,53].

However, caution should be exercized by synthesizing the findings about possible associates to adherence to DMARDs Citation[59]. Inconsistent findings could be explained by the differences among studies in methods of assessing (non-)adherence and its possible determinants. Furthermore, heterogeneity of characteristics of the study populations may have affected the validity of the synthesis of the results.

Unintentional & intentional adherence

Nonadherent RA patients seem hard to characterize by their (social) demographic, therapy-related and condition-related factors. These findings are confirmed in studies in other chronic diseases. Although more than 200 variables have been identified by researchers as influencing medication adherence Citation[60], no clear risk profiles could be constructed. Characteristics were often inconsistently correlated with nonadherence, were sometimes contradictory, and correlations were often weak. Furthermore, it is important to recognize that a person may have multiple risk factors for medication nonadherence. In addition, factors that can influence a person’s medication-taking behavior may change over time.

A valuable conceptual distinction that brings together the findings of different types of research and explanations of patients’ medication use is the distinction between ‘unintentional’ and ‘intentional’ nonadherence Citation[57,61–64]. Unintentional nonadherence reflects a person’s ability and skill at medicine-taking, including forgetting, poor manual dexterity, losing medicines or not being able to afford them.

Intentional nonadherence is a behavior driven by a decision not to take medicines. The drivers of this decision are complex but have been suggested to be based on beliefs about a patient’s illness and its (pharmacological) treatment. These beliefs can be categorized into perceived concerns and perceived benefits. Perceived concerns include side effects and dependence on mediation. Perceived benefits include a decrease in symptoms (pain, fatigue and wellbeing), prevention of functional loss and cure of the disease. Existing evidence suggests that beliefs about medicines are more predictive of intentional nonadherence than of unintentional nonadherence. In a sample of 173 patients with asthma, intentional nonadherence was most strongly predicted by a patients’ balance of the pros and cons of taking the medication Citation[63–65]. Conversely, unintentional nonadherence was not predicted by this balance of beliefs. The same association was found in a study of 117 patients who were taking antiretroviral medication Citation[66]. Intentional nonadherent patients seem to make a risk–benefit analysis, in which beliefs about the necessity of taking prescribed medications are weighed-up against concerns about possible negative effects Citation[52]. This balance of perceptions of necessity and concerns is consistent with the concepts of benefits and barriers in Rosenstock’s health belief model Citation[63,67]. This widely used model can be outlined using four constructs that represent the perceived threat and net benefits. According to this model, individuals will adhere with health regimens if they perceive themselves as being susceptible for getting a certain condition, if the condition has serious consequences, if the therapy would be beneficial, and if they feel that barriers to action are outweighed by the benefits Citation[68].

Only a few studies have addressed patients’ beliefs about medication as a possible predictor for adherence, although patients’ beliefs about medication can be easily assessed by the Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire Citation[63]. The scale is comprised of ten items: five items about the necessity of the medication and another five items on the concerns about medication. The Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire has been validated in various patient groups with chronic illnesses (asthma, diabetes, and renal and cardiovascular disease) and predicted adherence to treatment among various groups of patients with chronic conditions (e.g., people with asthma) Citation[15,69].

In studies with the Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire in patients with RA, it was found that most people with RA report positive beliefs about the necessity of their medication. More pain, fatigue, helplessness, the number of DMARDs along with physical disability increased the belief in the necessity of the medication. Levels of concern are, nonetheless, high, as 91% of the nonadherent patients had one or more concerns about potential adverse effects, particularly over the long term. Despite the positive association between adherence and factors such as necessity, degree of pain, fatigue, physical disability, perceived helplessness and the number of DMARDs prescribed, these factors were, on the other hand, also found to be positively related to concerns/barriers to taking medications Citation[69].

Based on Rosenstock’s ‘health belief’ model, and considering the conceptual distinction between intentional and unintentional behavior, we developed a simplified model to explain adherent behavior. This model suggests that once a patient receives a prescription, he/she will weigh up the necessity of the treatment (based on the patient’s perceived threat of the illness and his/her outcome expectancy) with the concerns for the treatment (expected disadvantages) Citation[69]. Therefore, patients make a risk–benefit analysis considering whether their beliefs about the necessity of the medication outweigh their concerns. When the necessity is stronger than the concerns, patients will intend to take their medication, and will take this medication unless practical unintentional barriers hinder the patient in taking their medication .

Interventions to improve adherence

Interventions in chronic diseases

Although clinicians and researchers have carried out a variety of interventions (diverse in approach and intensity) to improve adherence in chronic diseases, the effectiveness of these interventions was generally modest Citation[1,4,70,71]. Comprehensive interventions that combined approaches were typically more effective than interventions focusing on single causes of nonadherence; although the effect size was still small Citation[72,102]. However, few interventions really individualized the approach to match patients’ needs and preferences, in order to target a patient’s individual feelings on the necessity of the drug, his/her concerns and possible practical barriers for medication taking. Furthermore, only a few interventions have been systematically developed, with a theoretical model as a stepping stone and a structured identification of the targets of the intervention followed by a pilot session before the final randomized trial.

Interventions in RA

The modest effectiveness of adherence-improving interventions in chronic diseases is in line with the scarce results from research into medication adherence interventions in RA. Although education about medication and medication use, as well as self-management interventions, are often part of the treatment in RA, adherence is seldom reported as an outcome measure in studies into the effect of these interventions Citation[73]. Only three studies assessed the effect of a medication adherence intervention in RA using adherence as an outcome measure Citation[74–76]. One study demonstrated an improvement in adherence to D-penicillamine following a patient education program, including seven one-to-one visits of 30 min each Citation[14]. However, the second intervention study was not successful in increasing adherence to sulfasalazine among patients with active, recent-onset RA. Adherence to medication in participants of the patient education intervention (six group meetings) was already high at baseline. Both adherence intervention programs were intensive, with inconsistent results and limited effect at best. Finally, our group demonstrated that supplying written information about patients’ nonadherence and adherence to the rheumatologist was insufficient to increase patients’ adherence on drug therapy Citation[76].

Therefore, simple, easy to implement and effective interventions to improve adherence are needed in clinical practice Citation[103,77]. Some researchers suggest that adherence interventions can be improved by identifying and focusing the intervention on nonadherent patients only Citation[77]. Most existing interventions target all patients with a drug prescription, thus limiting the efficiency of the intervention. However, it is hard to identify nonadherent patients. Besides, adherence fluctuates and changes over time: adherent patients may become nonadherent ones.

A second promising strategy to improve the efficiency of adherence interventions is to tailor the content of the intervention to the individual patient’s cause(s) of nonadherence Citation[103,77].

Expert commentary

In conclusion, the effectiveness of RA therapy may be limited by inadequate adherence to medication and by discrepancies between the physician-prescribed regimen and the regimen actually used by the patient. Failure to take medication has important consequences; it not only reduces the efficacy of the treatment, but also wastes healthcare resources Citation[6,7]. Although knowledge of factors associated with medication adherence in RA could help health professionals to identify patients who would benefit from adherence-improving interventions, adherence seems to be influenced by patient characteristics that are less visible and more subtle, such as patient’s beliefs about their medication. These factors are more difficult to detect and need more time and attention from prescribers. Besides tackling practical barriers, such as forgetfulness, clinicians should therefore be sensitive to a patient’s personal beliefs that may impact medication adherence, and should discuss with their patient any concerns that they raise about prescribed medications.

Five-year view

Today, and in the future, patients receive more information about their health problems through accessing the internet, television and other media, where a myriad of (pharmacological) treatment options are regularly discussed. The wider availability of information empowers patients and will influence patients’ beliefs about the necessity of the drugs and their potential disadvantages. As it is ultimately the patient who decides on a daily basis whether or not to take their medication as prescribed, clinicians should take the empowered patient’s opinion into account to enable optimal medication use Citation[78].

Clinicians should discuss the patient’s perception of the need for the proposed treatment and consider the individual’s concerns about taking it throughout the course of therapy. This discussion will help to foster a patient–physician relationship in which the patient is able to communicate as a partner in the selection of treatment and the subsequent review of its effect. To achieve this shared decision-making, clinicians and patients need to be able to discuss concerns about treatment regimens. The aim of this discussion is concordance between patient and healthcare provider about diagnosis and prognosis of the illness, the treatment required and the risks and benefits associated with treatment. This point of view differentiates adherence (the extent to which the patient’s behavior matches agreed recommendations from the prescriber) from compliance (the extent to which a patient follows medical instruction). Simple interventions seem to be the most promising way to improve patient adherence, preferably when carried out in a multidisciplinary setting (physicians, psychologists and pharmacists) and, not in the least, by incorporating patients’ perspectives.

However, in order to measure the effectiveness of these interventions, more research on medication adherence in RA is necessary. Although the main priority for research is to develop effective and efficient interventions to facilitate a patient’s adherence, basic research on outcome measures to reliably assess adherence is necessary to adequately measure the extent of nonadherence and to objectify the effectiveness of medication adherence interventions. Finally, an improved understanding of the relationships between patients’ characteristics, patients’ cognitions, disease-related factors and patient–physician interaction should lead to more robust theoretical frameworks, and to more effective methods of improving adherence.

Table 1. Search strategy in PubMed for retrieving studies on medication adherence in rheumatoid arthritis.

Table 2. Methods to assess adherence.

Table 3. Studies assessing the extent of nonadherence to medication in rheumatoid arthritis.

Table 4. Factors associated and not associated with nonadherance in studies targeting disease-modifying antirheumatic drug adherence.

Key issues

• Adherence rates to prescribed medicine regimes in people with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) are low, varying from 30 to 80%. Improving adherence in RA could improve the efficacy of drug therapy in RA.

• Medication adherence can be divided into three major components: persistence; initiation adherence; and execution adherence.

• Medical decisions should be based on concordance: patients should be able to communicate as a partner in the selection of treatment and in the evaluation of effect.

• Currently, a gold standard for the measurement of adherence is not available.

• The appropriateness and choice of the specific measure employed should be determined by the overall goals of adherence measurement.

• Despite the heterogeneity of the available studies on disease-modifying antirheumatic drug nonadherence, all studies consistently show that disease-modifying antirheumatic drug adherence is suboptimal, with adherence rates ranging from 22 (underuse) to 107% (overuse).

• The variation in these studies relates to differences in the study groups, the duration of follow-up, the type of drugs included, the definition of adherence, the duration of the disease and the methods of assessment.

• Nonadherent RA patients seem hard to characterize by their (social) demographic, therapy-related and condition-related factors.

• Nonadherence behavior could conceptually be categorized into two subtypes: unintentional (due to forgetfulness, regimen complexity or physical problems); and intentional (based on a patient’s decision to take no/less medication).

• In case of intentional nonadherence, patients seem to make a benefit–risk analysis weighing the perceived risks of the treatment against the perceived benefits.

• Current methods for improving medication adherence in chronic diseases are often complex and not very effective.

• Most interventions that target adherence were not tailored to patients’ needs and preferences.

• Only one of the three studies assessing the effectiveness of a medication adherence intervention in RA demonstrated a slight improvement in adherence.

References

- Horne R, Weinman J. Predicting treatment adherence: an overview of theoretical models. In: Adherence to Treatment in Medical Conditions. Myers LB, Midence K (Eds). Harwood Academic Press, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 25–50 (1998).

- Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N. Engl. J. Med.353(5), 487–497 (2005).

- Lewis A. Noncompliance: a $100 billion problem. Remington Report5, 14–15 (1997).

- Haynes RB, Yao X, Degani A, Kripalani S, Garg A, McDonald HP. Interventions to enhance medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.4, CD000011 (2005) (Review). Update in: Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.2, CD000011 (2008).

- Jones G, Halbert J, Crotty M, Shanahan EM, Batterham M, Ahern M. The effect of treatment on radiological progression in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Rheumatology42, 6–13 (2003).

- Contreras-Yáñez I, Ponce De León S, Cabiedes J, Rull-Gabayet M, Pascual-Ramos V. Inadequate therapy behavior is associated to disease flares in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who have achieved remission with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Am. J. Med. Sci.340(4), 282–290 (2010).

- Viller F, Guillemin F, Briançon S, Moum T, Suurmeijer T, van den Heuvel W. Compliance to drug treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a 3 year longitudinal study. J. Rheumatol.26, 2114–2122 (1999).

- Belcon MC, Haynes RB, Tugwell P. A critical review of compliance studies in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum.27(11), 1227–1233 (1984).

- Dunbar J, Dunning EJ, Dwyer K. Compliance measurement with arthritis regimen. Arthritis Care Res.2(3), S8–S16 (1989).

- Elliott RA. Poor adherence to medication in adults with rheumatoid arthritis reasons and solutions. Dis. Manage. Health Outcomes16, 13–29 (2008).

- de Klerk E, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, van der Tempel H, Urquhart J, van der Linden S. Patient compliance in rheumatoid arthritis, polymyalgia rheumatica, and gout. J. Rheumatol.30, 44–54 (2003).

- Grijalva CG, Kaltenbach L, Arbogast PG, Mitchel EF Jr, Griffin MR. Adherence to disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and the effects of exposure misclassification on the risk of hospital admission. Arthritis Care Res.62(5), 730–734 (2010).

- Borah BJ, Huang X, Zarotsky V, Globe D. Trends in RA patients’ adherence to subcutaneous anti-TNF therapies and costs. Curr. Med. Res. Opin.25(6), 1365–1377 (2009).

- Curkendall S, Patel V, Gleeson M, Campbell RS, Zagari M, Dubois R. Compliance with biologic therapies for rheumatoid arthritis: do patient out-of-pocket payments matter? Arthritis Rheum.59(10), 1519–1526 (2008).

- van den Bemt BJ, van den Hoogen FH, Benraad B, Hekster YA, van Riel PL, van Lankveld W. Adherence rates and associations with nonadherence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis using disease modifying antirheumatic drugs. J. Rheumatol.36(10), 2164–2170 (2009).

- Doyle DV, Perrett D, Foster OJ, Ensor M, Scott DL. The long-term use of D-penicillamine for treating rheumatoid arthritis: is continuous therapy necessary? Br. J. Rheumatol.32, 614–617 (1993).

- Pullar T, Peaker S, Martin MF, Bird HA, Feely MP. The use of a pharmacological indicator to investigate compliance in patients with a poor response to antirheumatic therapy. Br. J. Rheumatol.27, 381–384 (1988).

- Brus H, van de Laar M, Taal E, Rasker J, Wiegman O. Determinants of compliance with medication in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the importance of self-efficacy expectations. Patient Educ. Couns.36, 57–64 (1999).

- Tuncay R, Eksioglu E, Cakir B, Gurcay E, Cakci A. Factors affecting drug treatment compliance in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol. Int.27(8), 743–746 (2007).

- Owen SG, Friesen WT, Roberts MS, Flux W. Determinants of compliance in rheumatoid arthritic patients assessed in their home environment. Br. J. Rheumatol.24(4), 313–320 (1985).

- Deyo RA, Inui TS, Sullivan B. Noncompliance with arthritis drugs: magnitude, correlates, and clinical implications. J. Rheumatol.8(6), 931–936 (1981).

- Garcia-Gonzalez A, Richardson M, Garcia Popa-Lisseanu M et al. Treatment adherence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin. Rheumatol.27(7), 883–889 (2008).

- Sackett DL, Haynes RB. Compliance with Therapeutic Regimens. John Hopkins University Press, London, UK (1976).

- Treharne GJ, Lyons AC, Hale ED, Douglas KM, Kitas GD. ‘Compliance’ is futile but is ‘concordance’ between rheumatology patients and health professionals attainable? Rheumatology45(1), 1–5 (2006).

- Salt E, Frazier SK. Adherence to disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a narrative review of the literature. Orthop. Nurs.29(4), 260–275 (2010).

- Arluke A. Judging drugs: patients’ conceptions of therapeutic efficacy in the treatment of arthritis. Hum. Organ.39(1), 84–88 (1980).

- De Klerk E. Measurement of patient compliance on drug therapy: an overview. In: Advances in Behavioral Medicine Assessment. Vingerhoets A (Ed.). Harwood Academic Publishers, London, UK, 215–244 (2001).

- Burnier M. Medication adherence and persistence as the cornerstone of effective antihypertensive therapy. Am. J. Hypertens.19(11), 1190–1196 (2006).

- Staples B, Bravender T. Drug compliance in adolescents: assessing and managing modifiable risk factors. Paediatr. Drugs4(8), 503–513 (2002).

- Vik SA, Maxwell CJ, Hogan DB. Measurement, correlates, and health outcomes of medication adherence among seniors. Ann. Pharmacother.38, 303–312 (2004).

- Roth HP, Caron HS. Accuracy of doctors ‘estimates and patients’ statements on adherence to a drug regimen. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther.23, 361–370 (1978).

- Gilbert JR, Evans CE, Haynes RB, Tugwell P. Predicting compliance with a regimen of digoxin therapy in family practice. Can. Med. Assoc. J.123, 119–1122 (1980).

- Andrade SE, Kahler KH, Frech F, Chan KA. Methods for evaluation of medication adherence and persistence using automated databases. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf.15(8), 565–574 (2006).

- Hess LM, Raebel MA, Conner DA, Malone DC. Measurement of adherence in pharmacy administrative databases: a proposal for standard definitions and preferred measures. Ann. Pharmacother.40(7–8), 1280–1288 (2006).

- Cramer JA, Mattson RH, Prevey ML, Scheyer RD, Ouellette VL. How often is medication taken as prescribed? A novel assessment technique. J. Am. Med. Assoc.261, 3273–3277 (1989).

- Schwed A, Fallab CL, Burnier M et al. Electronic monitoring of compliance to lipid-lowering therapy in clinical practice. J. Clin. Pharmacol.39, 402–409 (1999).

- McKenney JM, Munroe WP, Wright JT Jr. Impact of an electronic medication compliance aid on long-term blood pressure control. J. Clin. Pharmacol.32, 277–283 (1992).

- Waeber B, Vetter W, Darioli R, Keller U, Brunner HR. Improved blood pressure control by monitoring compliance with antihypertensive therapy. Int. J. Clin. Pract.53, 37–38 (1999).

- Hill J. Adherence with drug therapy in the rheumatic diseases part two: measuring and improving adherence. Musculoskeletal Care3(3), 143–156 (2005).

- Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med. Care.24, 67–74 (1986).

- Horne R. Compliance, adherence, and concordance: implications for asthma treatment. Chest130, S65–S72 (2006).

- de Klerk E, van der Heijde D, van der Tempel H, van der Linden S. Development of a questionnaire to investigate patient compliance with antirheumatic drug therapy. J. Rheumatol.26, 2635–2641 (1999).

- de Klerk E, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, van der Tempel H, van der Linden S. The compliance-questionnaire-rheumatology compared with electronic medication event monitoring: a validation study. J. Rheumatol.30, 2469–2475 (2003).

- Sewitch MJ, Dobkin PJ, Bernatsky S et al. Medication nonadherence in women with fibromyalgia. Rheumatology43, 648–654 (2004).

- Butler JA, Peveler RC, Roderick PJ, Horne R, Mason JC. Measuring compliance to drug regimes following renal transplantation: a comparison of self-report and clinician rating with electronic monitoring. Transplantation77, 786–789 (2004).

- Arnsten JH, Demas PA, Farzadegan H et al. Antiretroviral therapy adherence and viral suppression in HIV-infected drug users: comparison of self-reported and electronic monitoring. Clin. Infect. Dis.33, 1417–1423 (2001).

- Hugen PW, Langebeek N, Burger DM et al. Assessment of adherence to HIV protease inhibitors: comparison and combination of various methods, including MEMS (electronic monitoring), patient and nurse report, and therapeutic drug monitoring. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr.30, 324–334 (2002).

- Bangsberg DR, Hecht FM, Charlebois ED et al. Adherence to protease inhibitors, HIV-1 viral load, and development of drug resistance in an indigent population. AIDS14, 357–366 (2000).

- Liu H, Golin CE, Miller LG et al. Comparison study of multiple measures of adherence to HIV protease inhibitors. Ann. Intern. Med.134, 968–977 (2001).

- Cramer JA, Scheyer RD, Mattson RH. Compliance declines between clinic visits. Arch. Intern. Med.150(7), 1509–1510 (1990).

- van Dulmen S, Sluijs E, van Dijk L, de Ridder D, Heerdink R, Bensing J. International expert forum on patient adherence. Furthering patient adherence: a position paper of the International Expert Forum on Patient Adherence based on an internet forum discussion. BMC Health Serv. Res.27(8), 47 (2008).

- Treharne GJ, Lyons AC, Kitas GD. Medication adherence in rheumatoid arthritis: effects of psychosocial factors. Psychol. Health Med.9, 337–349 (2004).

- Park DC, Hertzog C, Leventhal H et al. Medication adherence in rheumatoid arthritis patients: older is wiser. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc.47, 172–183 (1999).

- Kumar K, Gordon C, Toescu V et al. Beliefs about medicines in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus: a comparison between patients of south Asian and White British origin. Rheumatology (Oxford)47(5), 690–697 (2008).

- Rogers PG, Bullman W. Prescription medicine compliance: review of the baseline of knowledge – report of the National Council on Patient Information and Education. J. Pharmacoepidemiol.3, 3–36 (1995).

- Beckles GL et al. Population-based assessment of the level of care among adults with diabetes in the U.S. Diabetes Care21, 1432–1438 (1998).

- Lorish CD, Richards B, Brown S. Missed medication doses in rheumatic arthritis patients: intentional and unintentional reasons. Arthritis Care Res.2(1), 3–9 (1989).

- Claxton AJ, Cramer J, Pierce C. A systematic review of the associations between dose regimens and medication compliance. Clin. Ther.23(8), 1296–1310 (2001).

- Ammassari A, Trotta MP, Murri R et al.; AdICoNA Study Group. Correlates and predictors of adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy: overview of published literature. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr.15(Suppl. 3), S123–S127 (2002).

- Cameron C. Patient compliance: recognition of factors involved and suggestions for promoting compliance with therapeutic regimens. J. Adv. Nurs.24(2), 244–250 (1996).

- Lorish CD, Richards B, Brown S Jr. Perspective of the patient with rheumatoid arthritis on issues related to missed medication. Arthritis Care Res.3(2), 78–84 (1990).

- Horne R. Representations of medication and treatment: advances in theory and assessment. In: Perceptions of Health and Illness. Petrie KJ, Weinman J (Eds). Harwood, Chur, Switzerland, 155–188 (1997).

- Horne R, Weinman J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J. Psychosom. Res.47, 555–567 (1999).

- Clifford S, Barber N, Horne R. Understanding different beliefs held by adherers, unintentional nonadherers, and intentional nonadherers: application of the necessity–concerns framework. J. Psychosomat. Res.64, 41–46 (2008).

- Wroe AL. Intentional and unintentional nonadherence: a study of decision making. J. Behav. Med.25, 355–372 (2002).

- Wroe AL, Thomas MG. Intentional and unintentional nonadherence in patients prescribed HAART treatment regimens. Psychol. Health Med.8, 453–463 (2003).

- Rosenstock IM. Why people use health services. Milbank Mem. Fund Q.44(3 Suppl.), 94–127 (1966).

- van den Bemt BJ, van Lankveld WG. How can we improve adherence to therapy by patients with rheumatoid arthritis? Nat. Clin. Pract. Rheumatol.3(12), 681 (2007).

- Neame R, Hammond A. Beliefs about medications: a questionnaire survey of people with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford)44(6), 762–767 (2005).

- van Dijk L, Heerdink ER, Somai D et al. Patient risk profiles and practice variation in nonadherence to antidepressants, antihypertensives and oral hypoglycemics. BMC Health Serv. Res.10(7), 51 (2007).

- No authors listed. Interventions to improve patient adherence with medications for chronic cardiovascular disorders, special report. TEC Bull. (Online)20, 30–32 (2003).

- Dolder CR, Lacro JP, Leckband S, Jeste DV. Interventions to improve antipsychotic medication adherence: review of recent literature. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol.23, 389–399 (2003).

- Riemsma RP, Kirwan J, Rasker J, Taal E. Patient education for adults with rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.2, CD003688 (2003).

- Hill J, Bird H, Johnson S. Effect of patient education on adherence to drug treatment for rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised controlled trial. Ann. Rheum. Dis.60(9), 869–875 (2001).

- Brus HLM, van de Laar MAFJ, Taal E, Rasker JJ, Wiegman O. Effects of patient education on compliance with basic treatment regimens and health in recent onset active rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheumat. Dis.57, 146–151 (1998).

- van den Bemt BJ, den Broeder AA, van den Hoogen FH et al. Making the rheumatologist aware of patients’ non-adherence does not improve medication adherence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Scand. J. Rheumatol.40(3), 192–196 (2011).

- Wetzels G, Nelemans P, van Wijk B, Broers N, Schouten J, Prins M. Determinants of poor adherence in hypertensive patients: development and validation of the ‘Maastricht Utrecht Adherence in Hypertension (MUAH)-questionnaire’. Patient Educ. Couns.64, 151–158 (2006).

- Misselbrook D. Why do patients decide to take their medicines? Prescriber9(7), 41–44 (1998).

- Taal E, Riemsma RP, Brus HL, Seydel ER, Rasker JJ, Wiegman O. Group education for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Patient Educ. Couns.20(2–3), 177–187 (1993).

Websites

- World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. (2003). www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_full_report.pdf

- Horne R, Weinman J, Barber N, Elliot R, Morgan M. Concordance, adherence and compliance in medicine taking. (2005). www.medslearning.leeds.ac.uk/pages/documents/useful_docs/76-final-report%5B1%5D.pdf

- Sluijs E, van Dulmen S, van Dijk L, de Ridder D, Heerdink R, Bensing J. Patient adherence to medical treatment: a meta review. (2006). www.nivel.nl/sites/default/files/bestanden/Patient-adherence-to-medical-treatment-a-meta-review.pdf

Medication adherence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a critical appraisal of the existing literature

To obtain credit, you should first read the journal article. After reading the article, you should be able to answer the following, related, multiple-choice questions. To complete the questions (with a minimum 70% passing score) and earn continuing medical education (CME) credit, please go to http://www.medscape.org/journal/expertimmunology. Credit cannot be obtained for tests completed on paper, although you may use the worksheet below to keep a record of your answers. You must be a registered user on Medscape.org. If you are not registered on Medscape.org, please click on the New Users: Free Registration link on the left hand side of the website to register. Only one answer is correct for each question. Once you successfully answer all post-test questions you will be able to view and/or print your certificate. For questions regarding the content of this activity, contact the accredited provider, [email protected]. For technical assistance, contact [email protected]. American Medical Association’s Physician’s Recognition Award (AMA PRA) credits are accepted in the US as evidence of participation in CME activities. For further information on this award, please refer to http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/category/2922.html. The AMA has determined that physicians not licensed in the US who participate in this CME activity are eligible for AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™. Through agreements that the AMA has made with agencies in some countries, AMA PRA credit may be acceptable as evidence of participation in CME activities. If you are not licensed in the US, please complete the questions online, print the AMA PRA CME credit certificate and present it to your national medical association for review.

Activity Evaluation: Where 1 is strongly disagree and 5 is strongly agree

1. You are seeing a 50-year-old woman with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). She is currently prescribed a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) plus medications for breakthrough pain, but she admits that she frequently does not take her medication as prescribed. What should you consider regarding the issue of treatment adherence as you treat this patient?

□ A >‘Compliance’ is currently the preferred term to describe patient adherence

□ B Beliefs about medicine are more predictive of intentional versus unintentional nonadherence

□ C Overall medication adherence rates for RA are 80–90%

□ D ‘Concordance’ relates to the extent to which patients’ behavior coincides with medical advice

2. You consider means to measure and ameliorate this patient’s nonadherence to therapy. Which of the following statements regarding means to measure adherence is most accurate?

□ A Patient self-reports lack specificity for detecting nonadherence

□ B Physicians’ estimates of patients’ adherence correlates well with objective pill counts

□ C The use of biological markers reflects only short-term adherence

□ D Multiple questionnaires specific to RA have been demonstrated to accurately measure treatment nonadherence

3. Which of the following is the best established risk factor for nonadherence among patients with RA?

□ A Reduced patient self-efficacy

□ B Older age

□ C Minimally active RA

□ D Poor overall perceived health

4. What should you consider regarding interventions to improve adherence?

□ A Interventions focused on the timing of medication use are more effective than more comprehensive interventions

□ B Interventions focused on the specific medication side effects are more effective than more comprehensive interventions

□ C All interventions tested to improve adherence in RA have generally been highly effective

□ D Most existing interventions target all patients with a prescription and not just nonadherent patients