Abstract

Childhood obesity is one of the most serious public health challenges of the 21st century with far-reaching and enduring adverse consequences for health outcomes. Over 42 million children <5 years worldwide are estimated to be overweight (OW) or obese (OB), and if current trends continue, then an estimated 70 million children will be OW or OB by 2025. The purpose of this review was to focus on psychiatric, psychological, and psychosocial consequences of childhood obesity (OBy) to include a broad range of international studies. The aim was to establish what has recently changed in relation to the common psychological consequences associated with childhood OBy. A systematic search was conducted in MEDLINE, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library for articles presenting information on the identification or prevention of psychiatric morbidity in childhood obesity. Relevant data were extracted and narratively reviewed. Findings established childhood OW/OBy was negatively associated with psychological comorbidities, such as depression, poorer perceived lower scores on health-related quality of life, emotional and behavioral disorders, and self-esteem during childhood. Evidence related to the association between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and OBy remains unconvincing because of various findings from studies. OW children were more likely to experience multiple associated psychosocial problems than their healthy-weight peers, which may be adversely influenced by OBy stigma, teasing, and bullying. OBy stigma, teasing, and bullying are pervasive and can have serious consequences for emotional and physical health and performance. It remains unclear as to whether psychiatric disorders and psychological problems are a cause or a consequence of childhood obesity or whether common factors promote both obesity and psychiatric disturbances in susceptible children and adolescents. A cohesive and strategic approach to tackle this current obesity epidemic is necessary to combat this increasing trend which is compromising the health and well-being of the young generation and seriously impinging on resources and economic costs.

Introduction

Childhood obesity is one of the most serious public health challenges of the 21st century. Over 42 million children <5 years worldwide are estimated to be overweight (OW) or obese (OB).Citation1,Citation2 OW and obesity (OBy), an established problem in high-income countries, is also an increasing problem in low- to middle-income countries (). More alarmingly, the increasing rate of childhood OW and OBy in developing countries is now >30% higher than that in developed countries. If current trends continue, then an estimated 70 million children will be OW or OB by 2025, making this a leading health problem.Citation2

Table 1 Global incidence of overweight and obesity in childhood

Childhood and adolescent OBy has far-reaching and enduring adverse consequences for health outcomes.Citation3,Citation4 In particular, the onset of psychiatric and psychological symptoms and disorders is more prevalent in OB children and young adults. Research has confirmed an association between childhood OW and OBy, psychiatric and psychological disorders, and onward detrimental effects on the psychosocial domainCitation5–Citation7 and overall quality of life (QoL).Citation8,Citation9 In turn, these can also compound their physical and medical health outcomes.Citation3,Citation4 Emerging research might strengthen the current body of knowledge in this area. Further review is required to explore the extent and implications of psychological comorbidities as well as identify important gaps for future research.

This review focuses on psychiatric, psychological, and psychosocial consequences of childhood OBy. It is the most recent review of this type and includes a broad range of studies involving numerous countries with varying methodologies. The aim was to establish what has recently changed in relation to the common psychological consequences associated with childhood OBy.

Methods

Data sources and searches

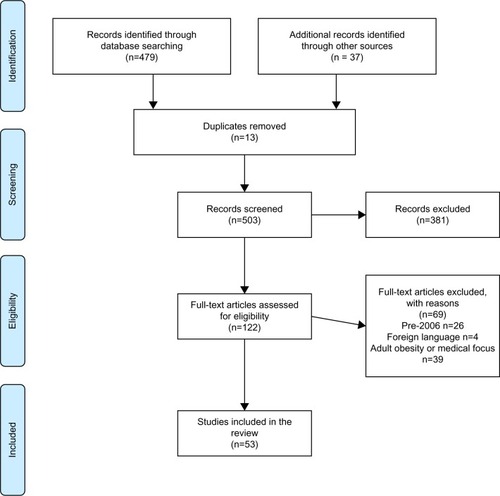

Three databases were searched, including MEDLINE (PubMed), Web of Science, and Cochrane Library. Search terms were developed with input from an subject expert librarian (). The search terms and strategy attempted to capture new information not included in previous reviews, including both prevention and treatment options, and findings from multiple countries. The full search was undertaken by one reviewer (JR). Then, another reviewer (LM) independently examined the titles and abstracts to identify suitable publications matching the selection criteria. Later, full texts were obtained for relevant articles and examined for inclusion in the final collection of review literature.

Table 2 Complete list of search terms

Study selection

All publications presenting information on the identification or prevention of psychiatric morbidity in childhood obesity were included. Articles for review were excluded if published before 2006, were unavailable in English, focused on medical/physiological outcomes or on obesity in adulthood (the cutoff age for adulthood varied and was determined by the authors of individual papers).

Preliminary search results

Databases were searched between June 13 and 17, 2016. Initial search results are presented in . Of 53 studies, 16 explored depression and anxiety, 17 investigated attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and conduct disorders (of which one also explored depression and anxiety), and 30 focused on other psychological comorbidities (of which 9 also included depression, anxiety, and/or ADHD).

Results

The reviewed 53 studies are summarized in – and are presented narratively below in relation to: 1) depression and anxiety, 2) ADHD, and 3) other psychological comorbidities including self-esteem, QoL, stigmatization, and eating disorders. Abbreviations for all outcome measures are detailed in .

Table 3 Summary of depression and anxiety papers (by authors in alphabetical order) (n=16)

Table 5 Summary of papers included in the review related to self-esteem, HRQoL, conduct, stigmatization, and eating disorders (by authors in alphabetical order) (n = 30)

Table 6 List of abbreviations and outcome measures cited in –

Depression and anxiety

Previous research findings about the relationship between depression and childhood OW/OBy suggest that weight gain during adolescence may be related to depression, negative mood states, and poor self-esteem.Citation7,Citation10

In relation to depression and anxiety, summarizes 16 studies that are currently reviewed. Diagnosis for depression and anxiety was confirmed either through diagnostic or clinical interview in 9 studiesCitation5,Citation11–Citation18 or through specifically focused validated questionnaires in 7 studies.Citation19–Citation25 Body mass index (BMI) was obtained through direct measurement, from documentation/clinical records or self-report, and body weight status was determined using national and international reference data and cutoff points criteria.Citation5,Citation11–Citation25 Study designs included prospective longitudinal,Citation13,Citation14,Citation18,Citation20,Citation23 cross-sectional,Citation15,Citation16,Citation19,Citation21,Citation22 population-based,Citation25 cohort,Citation24 clinical cohort,Citation11,Citation12 and retrospective studies.Citation5,Citation17

Numerous studies continue to report an association between depression and childhood OBy.Citation14–Citation16,Citation21,Citation22,Citation26 Anxiety disorders and stress associated with childhood OW/OBy are less well documented.Citation14,Citation16,Citation24 To date, related research studies have reported mixed findings.

Study findings varied in relation to the strength of association between depression and childhood OBy.Citation11,Citation15–Citation17,Citation19,Citation21 OW/OB children, compared with normal weight children, were found to be significantly more likely to experience depression as diagnosed by medical interview,Citation15,Citation16 with evidence that increasing weight in children was associated with increasing levels of psychosocial distress which is significantly correlated with depression, diagnosed by self-reported questionnaire.Citation21 Other studies of childhood OW/OBy did not support these findings and reported the prevalence of depression (medical diagnosis) being only modestly greater than the general population,Citation11 or having a weak association, as assessed by Child Depression Inventory (CDI) questionnaire.Citation19 In OB children, no statistically significant difference was found in the rates of most common psychiatric disorders including medical diagnosed depression.Citation5

Only a small number of studies have reported sex differences in OW/OB children/adolescents in relation to depression/anxiety.Citation14,Citation21,Citation22 OW/OB girls were reported to have a significantly greater increase in depression than OW/OB boys,Citation21 with greater odds of developing depression and anxiety with increasing weight.Citation14 OB girls also demonstrated more social anxiety than OB boys.Citation24 In contrast, OW/OB boys were found to be at higher odds of depressive symptoms than boys of normal weight.Citation22

Other relevant findings of interest relate to the older OB child (12–14 years) having an increased chance of developing depression and other internalizing disorders such as anxiety and paranoia.Citation17 Children also reporting stress on several levels have a significantly higher odds for becoming OB.Citation23

Findings from studies suggest greater psychopathology among OW/OB adolescents than non-OB adolescents.Citation11,Citation25,Citation27 OB children/adolescents are at more risk of diagnosed mood disorder in adulthood,Citation13 with OW/OB children and adolescents seeking psychiatric treatment and being diagnosed with depressionCitation5 and diagnosed bipolar disorders.Citation5,Citation11 OW/OB children/adolescents have been commonly reported to cope with an increased psychiatric burdenCitation11 and, when psychologically unhealthy, also more likely to report thoughts and attempts of suicide.Citation25

Family situations and influences also need to be considered while considering risk factors for childhood OBy and/or developing psychological disorders.Citation12,Citation23 Maternal mental health disorders predisposed OB children to a higher significant risk of anxiety,Citation12 and increased psychological and psychosocial stress in families may be a contributing factor for childhood OBy.Citation23

ADHD

ADHD is one of the most common childhood psychiatric disorders and is estimated to affect between 5% and 10% of young schoolchildren worldwide.Citation28 In relation to ADHD and childhood OBy, summarizes 17 studies that are currently reviewed. Study designs included longitudinal,Citation29–Citation32 cross-sectional,Citation33–Citation37 cohort,Citation38–Citation41 retrospective documentary analysis,Citation5,Citation42,Citation43 and secondary analysis.Citation44

Table 4 Summary of ADHD papers included in the review (by authors in alphabetical order) (n= 17)

ADHD diagnosis was confirmed through diagnostic/clinical interview in 11 studiesCitation5,Citation29,Citation31,Citation33,Citation34,Citation37–Citation39,Citation41–Citation43 and through ADHD-focused checklists and scales in 6 studies.Citation30,Citation32,Citation35,Citation36,Citation40,Citation44 Self-reporting was recognized to be a limitation in 1 study.Citation40 Body weight status was determined using either nationalCitation5,Citation31,Citation33,Citation35,Citation38,Citation41–Citation44 or international reference data and cutoff points criteria.Citation29,Citation30,Citation32,Citation36,Citation37,Citation39

Numerous studies have reported associations between ADHD and childhood OBy.Citation14,Citation30–Citation32,Citation35,Citation37 The strength of association between ADHD and childhood OBy varies across research studies. When compared to the general population, only 2 studies reported a significant association between OBy and ADHD symptoms with children/adolescents as assessed by clinical diagnosisCitation35,Citation43 and CPRS.Citation33 Other studies have reported an increased incidence of OB children with ADHD,Citation36 increased risk of becoming OB,Citation29,Citation30,Citation32 and increased odds of children with ADHD becoming OW when not using ADHD medication.Citation37

Children with ADHD and children displaying childhood conduct problems such as disobedience, defiance, aggression, cruelty to others, and destruction of property were prospectively associated with OW/OB young adults.Citation30,Citation31 These behaviors in early childhood were also predictive of disproportionate increase in BMI by early adolescenceCitation30 or early adulthood.Citation31

In contrast, a lower incidence of OW/OBy was noted in children with ADHD treatmentCitation34 while other studies did not find any association between ADHD and OW/OBy.Citation5,Citation40,Citation42,Citation45 Young OB adolescents are also reported to have lower rates of ADHD (self-reported) compared with healthy and underweight (UW) groups,Citation40 and children diagnosed with ADHD were more likely to be normal-weight or UW than OB.Citation5

Other psychological comorbidities

In relation to other psychological morbidities, summarizes 30 studies currently that are reviewed. Study designs included prospective longitudinal,Citation20,Citation31,Citation32,Citation46–Citation48 cross-sectional,Citation15,Citation16,Citation21,Citation49–Citation54 cohort,Citation24,Citation55–Citation63 and retrospective cohort/documentary analysis.Citation5,Citation17,Citation64–Citation66

Diagnosis of related psychological comorbidities was confirmed either through diagnostic or clinical interview in 6 studiesCitation5,Citation15–Citation17,Citation53,Citation64 or through specifically focused questionnaires in 24 studies.Citation20,Citation21,Citation24,Citation31,Citation32,Citation46–Citation52,Citation54–Citation63,Citation65,Citation66 All the studies obtained BMI data and determined weight status using national and international reference data and cutoff points criteria.

Self-esteem

Study findings confirmed that OW/OB children had significantly lower self-esteem than normal-weight peers, as measured by various focused questionnaires.Citation21,Citation49,Citation54 Findings confirmed that a clear negative impact on self-esteem was associated with OW/OB childrenCitation49,Citation54 who were more likely to have an increased child body dissatisfactionCitation21,Citation54 and lower perceived self-worth and self-competence than normal-weight peers.Citation49

Findings are mixed in relation to gender issues.Citation20,Citation49 OB girls completing a self-perception profile, compared with OB boys, had significantly more negative perceptions of their physical appearance, self-worth, and how they felt they were accepted by social groups, including their peers.Citation49 In contrast, no sex differences were found between psychological factors and weight problems with both sexes reporting the association with low self-esteem and OBy.Citation20 Self-esteem of OB children also appears to decrease with age with older children reporting significant reduction in self-esteem related to physical appearance than younger children.Citation21,Citation67 It is interesting to note that parenting is not associated with child body dissatisfaction but parental responsiveness to OW/OBy is positively associated with child self-esteem.Citation54

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL)

In research studies, childhood OBy is consistently associated with a poorer HRQoL when compared with lower-weight children.Citation24,Citation47,Citation48,Citation51,Citation55,Citation62,Citation63,Citation66 The findings for HRQoL tended to be consistent across the studies for both boys and girls. However, sex differences were noted in a study with OB treatment seeking patients with females reporting poorer HRQoL,Citation62 and females also reported lower HRQoL compared with males and healthy-weight females.Citation55 Severely OB children also reported depressive symptomology in the clinical range as assessed by Becks Depression Inventory Scale and marked impairments in both generic QoLCitation66 and HRQoL.Citation24,Citation63,Citation66 The association between increasing BMI and lower HRQoL being reported became stronger in later childhood.Citation51

Conduct and stigmatization

OW/OB children were more likely to experience multiple and clinically significant associated psychosocial problems than their healthy-weight peersCitation5,Citation21 with increasing conduct issues/disorders (such as disobedience, disruptive aggressive and destructive behavior, physical and verbal abuse).Citation5,Citation17,Citation31,Citation52 Other issues include peer problems,Citation51,Citation52,Citation60 inattention issuesCitation32 along with emotional symptoms.Citation51,Citation60 The association between symptoms and OW/OBy was found to be stronger with increasing age in childhood,Citation51 with increasing weight at younger ages (4–5 years) and associated with peer relationship problems at age 8–9 years.Citation61

Bullying and teasing, manifestations of OB stigma, were stressors associated with negative psychological outcomes and occurred more frequently in OW children.Citation68 Studies reported that persistent intense teasing and bullying experienced from childhood influences psychological complications.Citation15,Citation16,Citation58,Citation59,Citation69 OW/OB adolescents most distressed by weight-related teasing exhibited lower self-esteemCitation56,Citation59 and higher depressive disorders.Citation56,Citation58,Citation59 Primary sources of stigma for children and adolescents were reported to include peers, teachers/educators, parents, and health care providers.Citation58,Citation69–Citation71 OW/OB children being bullied and teased may also have less favorable conduct and poorer school performance, social circumstances, and social involvement when compared with normal-weight children.Citation70 Research findings reported that OW/OB children between 6 and 13 years were 4–8 times more likely to be teased and bullied than normal-weight peers.Citation21 OBy- and weight-related teasing is a significant risk factor for the development of psychosocial problems, including weight-based teasing, social stigmatization/peer rejection,Citation50 and later eating disorders and unhealthy weight-control behaviors.Citation58

Eating disorders

There is a clear overlap with OBy and eating disorders in several areas of psychosocial impairment with girls being more vulnerable to comorbid mood and eating problems.Citation72 Research findings revealed that 25% of OB girls used extreme weight-control behaviors such as inducing vomiting, abusing laxatives, diet pills, fasting, or smoking.Citation46 The relationship between OBy and eating behaviors in children/adolescents is evident with OB adolescents clearly at risk of developing a restrictive-eating disorder.Citation64,Citation65 There is a very high prevalence rate of mood disorders and significantly higher lifetime prevalence of bulimia nervosa in weight-loss-seeking patients with childhood OBy onset.Citation64 Studies have reported that OW/OB children and adolescents were more likely to report higher body dissatisfaction,Citation21,Citation54 display extreme dieting behaviourCitation47 and eating disorder symptoms, and clinically significant associated psychosocial problems than healthy-weight peers.Citation21

Prevention and interventions

Available evidence confirms that obesity can be treated effectively in younger childrenCitation73 and adolescents.Citation74 Multicomponent interventions targeting physical activity and healthy diet could benefit OW/OB children specifically in overall school achievement,Citation73 and family-based intervention with maintenance follow-up can improve psychosocial and physical QoL.Citation74 Systematic attempts to manage and treat OW in the early years and pre-school years are required.Citation47 A key focus on interventions should be on childhood/adolescent mental health, improving knowledge, and implementing high standard of treatment for OW children.Citation75 This needs to involve psychological and social support from families with recommendations about changing lifestyle.Citation23 In children with disruptive behavior disorders, secondary prevention and management strategies should include promoting healthy eating and physical activity to prevent adult OBy.Citation19,Citation44

Screening recommended

Routine screening of children with further comprehensive screening for high-risk populations.

Specific screening for various interrelated symptoms including OW/OBy, symptoms of impulsive eating behaviors, psychiatric disorders, psychological disturbances, and conduct-related issues.

Systematic screening for ADHD in OB adolescents with bulimic behaviors.Citation33

Early identification and intervention

Treating children and female anxiety and depression may be an important effort in the prevention of obesity.Citation14,Citation71

Physicians, parents, and teachers should be informed of specific comorbidities associated with childhood OBy to target interventions that could enhance well-being.Citation50

Interventions should recognize individual differences in terms of identifying motivating goals for accomplishing weight management.Citation61 Follow-up support is essential to maintain any straying from the short-term effects gained.Citation76

Family interventions need to focus on parenting/attachment issues, behavioral factors, or self-management interventions to implement healthy lifestyles.Citation57

Stigma-reduction efforts are needed to improve attitudes toward OBy.

Motivational interviewing in the treatment of obesity provides a more guiding style encouraging individuals to explore and understand their own intrinsic barriers and incentives to change.Citation61,Citation77

Future research

Future research needs well-designed prospective and hypothesis-driven longitudinal studies to further investigate specific areas (with different populations) and psychiatric and psychological outcomes. Appropriate control groups of clinical or nonclinical populations need to be included. Examples of future research in childhood obesity include further investigation of:

ADHD: 1) causality in the relationship between ADHD and OBy, and psychopathological pathways linking the two conditions; 2) experimental designs to establish cause and effect for BMI and HRQoL;Citation51 3) cause and effect of causal link between bulimic behaviors and ADHD and potential common neurobiological alterations;Citation33 4) OBy risks of young adults who manifest conduct problems in early life.Citation31

Body image: directional nature of relationships between body image and OBy as well as changes in psychosocial functioning.Citation24

Family functioning: influencing role and extent of parental, family functioning, peer, educator, or societal-related factors in psychological consequences.Citation12

Depression: 1) directional nature of sedentary behavior and onset of depression;Citation19,Citation78 2) moderating versus mediating roles of variables such as trait negative effect, depressive and anxiety symptoms, and low self-esteem and their influence on eating pathology.Citation56

Psychosocial: 1) role of psychosocial factors and treatment interventions that target extremely OB individuals based on their BMI, and socio-demographic profiles; 2) eating patterns and the dynamic relationship between binge eating and BMI.

Lifestyle: 1) causal relationships between physical activity behavior, motivation to change, BMI change and development of comorbid health conditions;Citation24 2) optimal strategies for encouraging lifestyle change and accomplishing weight management.Citation61,Citation77

Discussion

The purpose of this review was to focus on research findings related to psychiatric, psychological, and psychosocial consequences of childhood OBy from an international perspective. The precise extent of these complications remains uncertain due to the range of methodological approaches and methods used across studies. Causal mechanisms are not yet fully understood or convincing, but they are likely to involve a complex interplay of biological, psychological, and social factors.

Compared to healthy-weight children and adolescents, there seems to be a consistent heightened risk of psychological comorbidities including depression, compromised perceived QoL, depression and anxiety, self-esteem, and behavioral disorders. In turn, these disorders associated with OBy have a consistent adverse impact on their perceived HRQoL and psychiatric, psychological, and psychosocial disorders. These can be enduring in nature and may continue into adult life with the potential for lifelong health problems.

In general, consistent findings have established that childhood OW/OBy was negatively associated with psychological comorbidities, such as depression, poorer perceived HRQoL, emotional and behavioral disorders, and self-esteem during childhood. Findings are similar to other reviews in this periodCitation3,Citation28,Citation45,Citation72,Citation79–Citation82 in that OW/OB children and adolescents were more likely to experience psychological problems than healthy-weight peers. Findings suggest a shared link between depression and obesity such that OBy increases the risk of depression in adult life, but also that depression predicts the development of obesity.Citation26

Evidence related to the psychiatric disorder, ADHD, remains unconvincing because of various findings from studies. Many studies did report an association between ADHD and elevated weight status.Citation14,Citation30–Citation32,Citation35,Citation37 Children presenting with early and persistent ADHD in early and mid-childhood are also at an increased risk of OBy in adult life.Citation28 Therefore, the child with ADHD may be at risk of becoming OW or the OW child may be at risk for a diagnosis of ADHD. Some studies did not report any association between ADHD and OW/OBy.Citation5,Citation40,Citation42,Citation45 Other reviews also reported that the data were insufficient and inconsistent.Citation3,Citation4

This review found that OW children were more likely to experience multiple associated psychosocial problems than their healthy-weight peers. The strength of association between psychological disorders, psychosocial problems, and OW may also depend upon OBy stigma, teasing, and treatment-seeking children.Citation66,Citation71,Citation82,Citation83 This stigmatization is now a common event within society and may be evidenced in the form of negative stereotypes, victimization, and social marginalization.Citation83 OBy stigma and teasing/bullying are pervasive and can have serious consequences for emotional and physical health. Stigma may be linked to obesity being the target of many public health campaigns that influence young OW/OB children and adolescents to control their weight, often through drastic measures.Citation46,Citation83 This means that psychiatric symptoms or disorders may be a consequence of being OB in a culture that stigmatizes OBy. Alternatively psychiatric disorders may contribute to the development of obesity in vulnerable individuals.Citation84

Intervention and action are necessary to prevent childhood and adolescent OBy.Citation1 Children are particularly vulnerable as both obesity and psychiatric conditions often have their origins during this crucial developmental period.Citation79 If obesity remains in adolescence, then it is likely to persist into adult life.Citation14,Citation85

Conclusion

The aim of this review was to establish what has recently changed in relation to common psychological consequences associated with childhood OBy. Despite extensive research being undertaken over the previous decade, it remains unclear as to whether psychiatric disorders and psychological problems are a cause or a consequence of childhood obesity. The prevalence of both childhood OW/OBy and associated psychiatric and psychological disorders is increasing, and there is an acute heightened awareness of this serious public health issue in the society and health-related policy. However, it is also still not proven whether common factors promote both obesity and psychiatric disturbances in susceptible children and adolescents. This finding in itself reflects the challenge of researching and understanding the complex factors associated with childhood OBy and psychological well-being. This review has illustrated that OW/OB children are more likely to experience the burden of psychiatric and psychological disorders in childhood, adolescence, and possibly into adulthood. A cohesive and strategic approach to tackle the OBy epidemic is necessary to combat this increasing trend which is compromising the health and well-being of the young generation and seriously impinging on resources and economic costs. As a matter of urgency, further focused research is essential to identify the diverse range of mechanisms driving the current increasing trajectory. Reliable and convincing evidence is needed to inform policy, economic regulation interventions, and strategies to prevent OBy from affecting future generations.

Disclosure

LM’s time on this research was funded by UK Medical Research Council core funding as part of the MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit “Social Relationships and Health Improvement” program (MC_UU_12017/11) and “Complexity in Health Improvement” program (MC_ UU_12017/14). The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- World Health OrganisationObesity and overweight factsheet no. 311Geneva2016

- NgMFlemingTRobinsonMGlobal, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013Lancet2014384994576678124880830

- PulgaronERChildhood obesity: a review of increased risk for physical and psychological comorbiditiesClin Ther2013351A18A3223328273

- SandersRHHanABakerJSCobleySChildhood obesity and its physical and psychological co-morbidities: a systematic review of Australian children and adolescentsEur J Pediatr201517471574625922141

- MarksSShaikhUHiltyDMColeSWeight status of children and adolescents in a telepsychiatry clinicTelemed J E Health2009151097097420028189

- WilfleyDEVannucciAWhiteEKEarly intervention of eating- and weight-related problemsJ Clin Psychol Med Settings201017428530020960039

- GoodmanEWhitakerRCA prospective study of the role of depression in the development and persistence of adolescent obesityPediatrics200211049750412205250

- SchwimmerJBBurwinkleTMVarniJWHealth-related quality of life of severely obese children and adolescentJAMA2003289141813181912684360

- WilliamsJWakeMHeskethKMaherEWaltersEHealth-related quality of life of overweight and obese childrenJAMA20052931707615632338

- PineDSGoldsteinRBWolkSWeissmanMMThe associations between childhood depression and adulthood body mass indexPediatrics200310710491056

- GoldsteinBIBirmaherBAxelsonDAPreliminary findings regarding overweight and obesity in pediatric bipolar disorderJ Clin Psychiatry200869121953195919026266

- RothBMunschSMeyerAIslerESchneiderSThe association between mothers’ psychopathology, childrens’ competences and psychological well-being in obese childrenEat Weight Disord200813312913619011370

- SandersonKPattonGCMrKercherCDwyreTVemAJOverweight and obesity in childhood and risk of mental disorders: a 20-year cohort studyAust N Z J Psych201145384392

- AndersonSECohenPNaumovaENMustAAssociation of depression and anxiety disorders with weight change in a prospective community-based study of children followed up into adulthoodArch Pediatr Adolesc Med2006160328529116520448

- BellLMByrneSThompsonAIncreasing BMI z-scores is continuously associated with complications of overweight children, even in healthy weight rangesJ Clin Endocrinol Metab20079251752217105842

- BellLMCurranJAByrneSHigh incidence of obesity comorbidities in young children: a cross sectional studyJ Pediatr Child health201147911917

- EschenbeckHKohlmannCWDudeySSchurholzTPhysician-diagnosed obesity in German 6- to 14-year-olds. Prevalence and comorbidity of internalizing disorders, externalizing disorders, and sleep disordersObesity Facts200922677320054208

- AndersonSECohenPNaumovaENJacquesPFMustAAdolescent obesity and risk for subsequent major depressive disorder and anxiety disorder: prospective evidencePsychosom Med200769874074717942847

- AntonSDNewtonRLJrSothernMMartinCKStewartTMWilliamsonDAAssociation of depression with body mass index, sedentary behavior, and maladaptive eating attitudes and behaviors in 11 to 13-year old childrenEat Weight Disord2006113e102e10817075232

- BjornelvSNordahlHMHomenTLPsychological factors and weight problems in adolescents. The role of eating problems, emotional problems and personality traits: the Young-HUNT studySoc Psychiatry Psychiatri Epidemiol2011465353362

- GibsonLYByrnSMBlairEDaviesEAJakobiPZubrickSRClusters of psychological symptoms in overweight childrenAust N Z J Psych200842118125

- HoareEMillarLFuller-TyszkiewiczMAssociations between obesogenic risk and depressive symptomatology in Australian adolescents: a cross sectional studyJ Epidemiol Community Health20146876777224711573

- KochFSepaALudvigssonJPsychological stress and obesityJ Pediatr200815383984418657829

- PhillipsBAGaudetteSMcCrackenAPsychosocial functioning in children and adolescents with extreme obesityJ Clin Psychol Med Settings201219327728422437944

- van WijnenLGBolujitPRHoeven-MulderHBBernelmansWJWndel-VosGCWeight status, psychological health, suicidal thoughts, and suicide attempts in Dutch adolescents: results from the 2003 E-MOVO projectObesity2010181059106119834472

- LuppinoFSde WitLMBouvyPFOverweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studiesArch Gen Psychaitr201067220229

- SwansonSACrowSLe GrangeDPrevalence and correlates of eating disorders in adolescentsArch Gen Psychiatry201168771472321383252

- CorteseSAngrimanMMaffeisCAttention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and obesity: a systematic review of the literatureCrit Rev Food Sci Nutr200848652453718568858

- AndersonSECohenPNaumovaENMustARelationship of childhood behavior disorders to weight gain from childhood into adulthoodAmbul Pediatr2006629730117000421

- AndersonSEHeXSchoppe-SullivanSMustAExternalizing behavior in early childhood and body mass index from age 2 to 12 years: longitudinal analyses of a prospective cohort studyBMC Pediatr2010104920630082

- DuarteCSSouranderANikolakarosGChild mental health problems and obesity in early adulthoodJ Pediatr20101561939719783001

- KhalifeNKantomaaMGloverVChildhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms are risk factors for obesity and physical inactivity in adolescenceJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry201453442543624655652

- CorteseSIsnardPFrelutMLAssociation between symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and bulimic behaviors in a clinical sample of severely obese adolescentsInt J Obes2007312340346

- Dubnov-RazGPerryABergerIBody mass index of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderJ Child Neurol201126330230820929910

- ErhartMHerpertz-DahlmannBWilleNSawitzky-RoseBHöllingHRavens-SiebererUExamining the relationship between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and overweight in children and adolescentsEur Child Adolesc Psychiatry2012211394922120761

- KimJMutyalaBAgiovlasitisSFernhallBHealth behaviors and obesity among US children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder by gender and medication usePrev Med2011523–421822221241728

- WaringMELapaneKLOverweight in children and adolescents in relation to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: results from a national samplePediatrics20081221e1e618595954

- ByrdHCMCurtinCAndersonSEAttention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and obesity in US males and females, age 8–15yrs: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2004Pediatr Obes2013844545323325553

- GrazianoPABagnerDMWaxmonskyJGReidAMcNamaraJPGeffkenGRCo-occurring weight problems among children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: the role of executive functioningInt J Obes2012364567572

- RojoLRuizEDominquezJACalafMLivianosLComorbdiity between obesity and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: population study with 13–15 year oldsInt J Eat Disord20063519522

- YangRMaoSZhangSLiRZhaoZPrevalence of obesity and overweight among Chinese children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a survey in Zhejiang province, ChinaBMC Psychiatry2013131331313323297686

- Pauli-PottUNeidhardJHeinzel-GutenbrunnerMBeckerKOn the link between attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and obesity: do comorbid oppositional defiant and conduct disorder matter?Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry201423753153724197170

- RacickaEHancTGiertugaKBrynskaAWolanczykTPrevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents with ADHD: the significance of comorbidities and pharmacotherapyJ Atten Disord Epub2042015

- WhiteBNichollsDChristieDColeTJVinerRMChildhood psychological function and obesity risk across the lifecourse: findings from the 1970 British Cohort StudyInt J Obes2012364511516

- NiggJTJohnstoneJMMusserEDGalloway LongHWilloughbyMTShannonJAttention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and being overweight/obesity: new data and meta-analysisClin Psychol Rev201643677926780581

- Neumark-SztainerDWallMHainesJStoryMSherwoodNEvan der BergPShared risk and protective factors for overweight and disordered eating in adolescentsAm J Prev Med20073335936917950400

- WakeMCanterfordLPattonGCComorbidities of overweight/obesity experienced in adolescence: longitudinal studyArch Dis Child201095316216819531529

- WakeMCliffordSAPattonGCMorbidity patterns among the underweight, overweight and obese between 2–18yrs: population-based cross-sectional analysisInt J Obes2013378693

- FranklinJDenyerGSteinbeckKSCatersonIDHillAJObesity and risk of low self-esteem: a statewide survey of Australian childrenPediatrics20061182481248717142534

- HalfonNLarsonKSlusserWAssociations between obesity and comorbid mental health, developmental, and physical health conditions in a nationally representative sample of US children aged 10 to 17Acad Pediatr201313161323200634

- JansenPWMensahFKCliffordSBidirectional associations between overweight and health-related quality of life from 4–11 years: Longitudinal Study of Australian ChildrenInt J Obes (Lond)201337101307131323736370

- SawyerMGMiller-LewisLGuySWakeMCanterfordLKarlinJBIs there a relationship between overweight and obesity and mental health problems in 4–5yr old Australian childrenAmbul Pediatr2006630631117116602

- TanerYTorel-ErgurABahcivanGGurdagMPsychopathology and its effect on treatment compliance in pediatric obesity patientsTurkish J Pediatr2009515466471

- TaylorAWilsonCSlaterAMohrPSelf-esteem and body dissatisfaction in young children and associations with weight and parenting styleClin Psychol2012162535

- BoltonKKremerPRossthornNThe effect of gender and age on the association between weight status and health-related quality of life in Australian adolescentsBMC Public Health20141489825183192

- GerkeCKMazzeoSESternMPalmbergAAEvansRKWickhamEP3rdThe stress process and eating pathology among racially diverse adolescents seeking treatment for obesityJ Pediatr Psychol201338778579323853156

- JohnstonCAFullertonGMorenoJPTylerCForeytJPEvaluation of treatment effects in obese children with co-morbid medical or psychiatric conditionsGeorgian Med News2011196–19793100

- MadowitzJKnatzSMaginotTCrowSJBoutelleKNTeasing, depression and unhealthy weight control behaviour in obese childrenPediatr Obes20127644645222991215

- QuinlanNPHoyMBCostanzoPRThe effects of teasing on psychosocial functioning in an overweight treatment-seeking sampleSoc Dev200918978100126166950

- SawyerMGHarcharkTWakeMLynchJFour year prospective study of BMI and mental health problems in childrenPediatrics201112867768421930536

- Walders-AbramsonNNadeauKJKelseyMMPsychological functioning in adolescents with obesity co-morbiditiesChild Obes20139431932523763659

- WilleNBullingerMHollRHealth-related quality of life in overweight and obese youths: results of a multicentre studyHealth Qual Life Outcomes20108364420374656

- ZellerMHModiACPredictors of health-related quality of life in obese youthsObesity (Silver Spring)20061412213016493130

- GuerdjikovaAIMcElroySLKotwalRStanfordKKeckPEJrPsychiatric and metabolic characteristics of childhood versus adult-onset obesity in patients seeking weight managementEat Behav20078226627617336797

- LebowJSimLAKransdorfLNPrevalence of a history of overweight and obesity in adolescents with restrictive eating disordersJ Adolesc Health2015561192425049202

- ZellerMHRoehrigHRModiACHealth-related quality of life and depressive symptoms in adolescents with extreme obesity presenting for bariatric surgeryPediatrics20061171155116116585310

- DanielsSRJacobsonMSMcCrindleBWAmerican Heart Association childhood obesity research summit reportCirculation2009119e489e51719332458

- Neumark-SztainerDFalknerNStoryMPerryCHannanPJMulertSWeight-teasing among adolescents: correlations with weight status and disordered eating behaviorsInt J Obes Relat Metab Disord20022612313111791157

- Hayden-WadeHASteinRIGhaderiASaelensBEZabinskiMFWilfleyDEPrevalence, characteristics, and correlates of teasing experiences among overweight children vs. non-overweight peersObes Res20051381381139216129720

- MaloneyAEPediatric obesity: a review for the child psychiatristChild Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am20101935337020478504

- PuhlRMLatnerJDStigma, obesity, and the health of the nation’s childrenPsychol Bull2007133455758017592956

- RancourtDMcCulloughMBOverlap in eating disorders and obesity in adolescenceCurr Diabet Rep2015151078

- MartinASaundersDHShenkinSDSprouleJLifestyle intervention for improving school achievement in overweight or obese children and adolescentsCochrane Database Syst Rev20143CD00972824627300

- FennerAAHowieEKDavisMCStrakerLMRelationships between psychosocial outcomes in adolescents who are obese and their parents during a multi-disciplinary family-based healthy lifestyle intervention: one year follow-up of a waitlist controlled trialHealth Qual Life Outcomes20161410011627389034

- BarlowSEExpert Committee. Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary reportPediatrics2007120SupplS164S19218055651

- WilfleyDESteinRISaelensBEEfficacy of maintenance treatment approaches for childhood overweight: a randomized controlled trialJAMA2007298141661167317925518

- ArmstrongMJMottersheadTARonksleyPEMotivational interviewing to improve weight loss in overweight and/or obese patients. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trialsObes Rev20111270972321692966

- ReillyJJArmstrongJDorostyAREarly life risk factors for obesity in childhood: cohort studyBMJ2005330135715908441

- KalarchianMAMarcusMDPsychiatric comorbidity of childhood obesityInt Rev Psychiatry201224324124622724645

- HarrigerJAThompsonJKPsychological consequences of obesity: weight bias and body image in overweight and obese youthInt Rev Psychiatry201224324725322724646

- KalraGDe SousaASonovaneSShahNPsychological issues in pediatric obesityInd Psychiatry J201221111723766572

- WardleJWilliamsonSJohnsonFDepression in adolescent obesity: cultural moderators of the association between obesity and depressive symptomsInt J Obes200630634643

- Tang-PéronardJLHeitmannBLStigmatization of obese children and adolescents, the importance of genderObes Rev200886522534

- GadallaTPiranNPsychiatric comorbidity in women with disordered eating behavior: a national studyWomen Health200848446748419301534

- ReillyJJLong term impact of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence on morbidity and premature mortality in adulthood; systematic reviewInt J Obes2011357891898

- National Center for Health StatisticsHealth, United States, 2011: With Special Features on Socioeconomic Status and HealthHyattsville, MD2012

- OgdenCLCarrollMDKitBKFlegalKMPrevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012JAMA2014311880681424570244

- World Health OrganisationA Snapshot of the Health of Young People in EuropeGenevaEuropean Commission Conference on Youth Health2009

- SassiFDevauxMCecchiniMRusticelliEThe obesity epidemic: analysis of past and projected future trends in selected OECD countriesParis CedexOECD Publishing2009

- Australian Bureau of StatisticsAustralian Health Survey: updated results, 2011–20122013 Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Lookup/4364.0.55.003main+features12011-2012Accessed July 1, 2016