Abstract

As stroke care has developed, there has been a need to robustly assess the efficacy of interventions both at the level of the individual stroke survivor and in the context of clinical trials. To describe stroke-survivor recovery meaningfully, more sophisticated measures are required than simple dichotomous end points, such as mortality or stroke recurrence. As stroke is an exemplar disabling long-term condition, measures of function are well suited as outcome assessment. In this review, we will describe functional assessment scales in stroke, concentrating on three of the more commonly used tools: the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale, the modified Rankin Scale, and the Barthel Index. We will discuss the strengths, limitations, and application of these scales and use the scales to highlight important properties that are relevant to all assessment tools. We will frame much of this discussion in the context of “clinimetric” analysis. As they are increasingly used to inform stroke-survivor assessments, we will also discuss some of the commonly used quality-of-life measures. A recurring theme when considering functional assessment is that no tool suits all situations. Clinicians and researchers should chose their assessment tool based on the question of interest and the evidence base around clinimetric properties.

Why measure functional outcomes in stroke trials?

Large-scale clinical trials have created a robust evidence base to inform much of what is now standard acute-stroke practice.Citation1–Citation3 The classical clinical trial is designed to test efficacy of a particular intervention over a comparator, for example, placebo or “usual care.” To facilitate comparison between the groups requires a standard measure of outcome that is relevant and suited to the clinical question, valid for the population studied, and meaningful to the research team. In those trials that describe interventions designed to impact on quantifiable physiological variables, such as glycemia or blood pressure, choice of end-point assessment is reasonably straightforward. Choice of assessment strategy is more challenging for a chronic, nonprogressive, or variably progressive disorder with potential multisystem effects such as cerebrovascular disease. “Hard” clinical end points such as stroke mortality or stroke recurrence are useful, but do not fully capture the potential devastating effect of a disabling but survivable stroke. As stroke represents the leading global cause of adult disability,Citation4 an important consideration for any study of stroke interventions is functional recovery. This is recognized by regulatory authorities, who now recommend a measure of functional recovery/disability as primary or coprimary end point for stroke intervention trials.

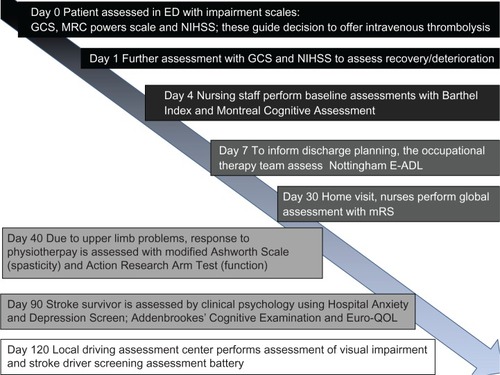

Although the focus of this review will be functional assessment tools for stroke trials, these instruments also have utility in clinical practice. As functional assessment scales give a numerical value to abstract concepts such as “disability,” they can be used to objectively quantify deficits and track change over time. This can be particularly useful in a rehabilitation setting. In clinical practice, an appreciation of how to describe stroke recovery in terms of common stroke scales allows for development of a common language between professionals caring for stroke survivors that facilitates comparisons of patients and services. Within a single review, it would be impossible to review all stroke-specific and generic scales that may be needed in a stroke survivor’s journey (). For the interested reader, we recommend a number of reference works.Citation5–Citation7 We recognize there is also extensive literature on assessment strategies for cognitive function poststroke. We will not review cognitive testing, suffice to say that there are a multitude of tools available with little consistency in choice of assessment.Citation8

Figure 1 Scales used at various points in the stroke survivor’s journey.

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; E-ADL, extended activities of daily living; mRS, modified Rankin Scale; QOL, quality of life; MRC, Medical Research Council.

Which functional measure to use

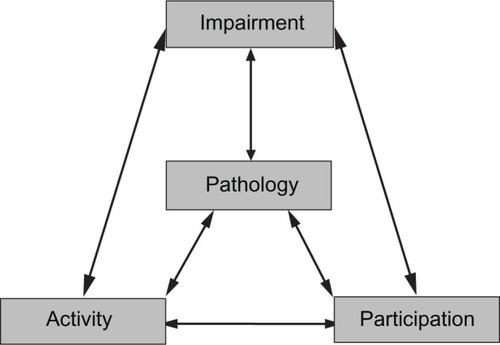

A large number of stroke-assessment scales are described, with novel scales frequently appearing (and often subsequently disappearing) in the literature. For those who are new to functional assessment, the large and varied nature of available scales and tools may seem daunting. The World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (WHO-ICF)Citation9 gives a conceptual framework that can aid classification of the scales and help decide on the appropriate measure for a particular purpose.

WHO-ICF describes levels of pathology (in this case, the stroke lesion), impairments (the direct loss of function), activity limitation (formerly called disability), and societal participation (formerly called handicap). The WHO-ICF grades do not exist in isolation; they interact and often create feedback loops. For example, an ischemic stroke (pathology) may cause a hemianopia (impairment); this may lead to poor mobility (activity limitation) and may restrict the stroke survivor from driving (societal participation limitation). These problems may result in a fall with soft-tissue injury (impairment), and fear of falling may cause the stroke survivor to forgo usual hobbies and activities (societal participation limitation) ().

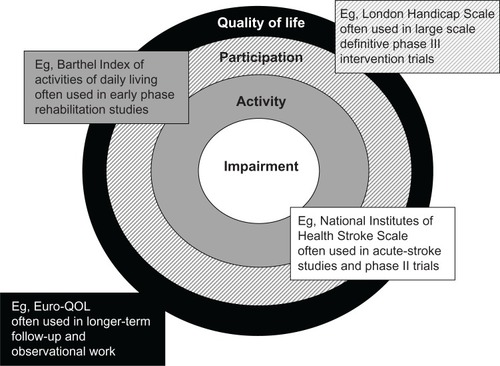

Tools that assess stroke at all these levels are available. Measures of pathology (for example, size of infarct on imaging) or impairment (for example the Medical Research Council Motor Assessment Scale) are straightforward to perform and interpret, but give little useful information on how stroke affects the individual. For this reason, impairment scales are often used in early phase trials. For phase III studies, activity measures or measures of participation are usually preferred. Although not part of the WHO-ICF, a further concept of quality of life (QOL) is also described, and tools exist for its measurement. Measures of QOL give a far more detailed assessment, but as a result can be more burdensome to the patient and are often more difficult to interpret ().

Clinimetric properties of scales

Clinimetrics is the study of properties of clinical assessment tools;Citation10 the term is derived from the theory of psychometrics.Citation11 Classical test theory describes important properties such as validity and reliability.Citation12 Other important factors for clinical scales are acceptability, both to patient and to assessor, and responsiveness to change. Although in psychometrics, classical test measures are increasingly being superseded by contemporary theories of “item response,” the measures of validity, reliability, and responsiveness remain important for understanding clinical scales, and we will discuss them in turn.

The clinimetric property of validity seeks to assess whether a scale measures the concept it purports to measure. Adequate validity is essential for a stroke scale to have clinical utility, as a functional assessment tool that does not measure function is meaningless. Validity can be assessed in various complementary ways.Citation5–Citation7 There is no “gold standard” for poststroke function, so assessment of criterion validity, where a scale is compared to a reference standard, is not possible. However, concurrent validity can be applied to a stroke scale by comparing it with another measure that purports to measure a similar construct; for example, comparing a novel impairment scale with an established scale. Face validity is an assessment of whether a priori the scale should measure the concept of interest, usually assessed by experts in the field. Content validity asks whether the various items of a scale can adequately describe the concept of interest. Prognostic or predictive validity for a stroke scale may be examined by, for example, studying if an impairment scale is associated with longer-term stroke outcomes.

Reliability is a measure of consistency in scoring. For stroke scales, important reliability measures include the reproducibility of repeat scoring by the same observer (intraobserver reliability or test–retest reliability) and between scorers (interobserver variability). Whether all items within a scale measure the same construct is a further measure of reliability, usually termed internal consistency. In contemporary stroke trials, where many thousands of stroke survivors may be assessed by hundreds of international research teams, reliability of assessment is clearly paramount. Whereas validity of a scale is inherent, reliability of assessment may be modified. Various methods to improve consistency of assessment are employed in large-scale trials, including training in use of scales, certification exams, and use of standardized protocols. While validity is relative, reliability can be objectively described. There is no consensus on the optimal method to measure reliability, although kappa statistics are frequently used in the biomedical literature to assess agreement. Kappa statistics quantify agreement above that which would be expected by chance. A kappa of 0 would imply no agreement other than that expected by chance, and perfect agreement is scored as 1.0. Traditionally, a kappa greater than 0.6 is taken as sufficient agreement to justify use of a scale. Various forms of statistical “weighting” of kappa values can be used to give a measure of the degree of difference between raters.Citation13,Citation14 Increasingly, more sophisticated analyses, such as that of Bland–Altman, are being used to assess reliability.Citation15

Responsiveness can be thought of as the ability to detect meaningful change over time. Meaningful change is clearly a subjective term, and will vary with the context in which the scale is used. The issue of responsiveness and the ability to detect small but meaningful change is especially important for a condition with high incidence and prevalence, such as stroke. If a scale does not pick up change in function, treatment effects that are modest for the individual but potentially important at a population level could be missed.

The ideal scale would be easy and quick to administer, acceptable to patients and researchers, valid for its chosen purpose, reliable, and responsive to meaningful clinical change. There is no ideal stroke measure that fulfills all these criteria (nor is there ever likely to be). Although some guidance on stroke assessment for trials is emerging, debate continues as to the relative strengths and limitations of differing assessment strategies, and there is no consensus as to the optimal outcome measure(s) for use.

The stroke literature describes a variety of instruments, generic and specific to stroke, for functional assessment of recovery. A recent analysis of tools used in stroke trials suggests substantial heterogeneity in choice of assessment measure and in method of application.Citation16 Use of bespoke, nonvalidated assessments is still seen, although less commonly than previously. Certain assessments are used more frequently than others and are increasingly recommended by specialist societies.Citation17 For the non-stroke specialist, a basic knowledge of the more prevalent stroke scales will allow for improved understanding and critical analysis of stroke studies. We will describe three common stroke assessments: the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS), the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) and the Barthel Index (BI). We will also discuss some of the commonly used QOL scales. For each scale, we will discuss history, development, and application, and use the scales to further discuss the importance of clinimetric properties.

The scientific study of assessment scales, particularly stroke assessment, is rapidly expanding and it would be impossible to comprehensively cover all areas. In this review, we will not describe the optimal analysis of functional scales for stroke trials. Debate continues as to the relative merits of various statistical techniques, including dichotomization and use of the complete range of a scale, with the differing approaches having vocal proponents.Citation18,Citation19 Equally, we will not consider the literature on outcome assessment in animal models of stroke.Citation20,Citation21

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

The NIHSS is a 15-item scale that standardizes and quantifies the basic neurological examination, paying particular attention to those aspects most pertinent to stroke. The NIHSS provides an ordinal, nonlinear measure of acute stroke-related impairments by assigning numerical values to various aspects of neurological function.Citation22 The scale incorporates assessment of language, motor function, sensory loss, consciousness, visual fields, extraocular movements, coordination, neglect, and speech.Citation22 It is scored from 0 (no impairment) to a maximum of 42. Scores of 21 or greater are usually described as “severe.” A standardized approach to assessment, starting with fundamental assessments such as level of consciousness, is recommended, and guidance is given on how to score where the stroke survivor is not able to respond to commands.

The NIHSS was developed in the early 1980s as a research tool to allow consistent reporting of neurological deficits in acute-stroke studies, particularly the early trials of thrombolysis and putative neuroprotectants.Citation22 The NIHSS was developed through a robust consensus approach, taking the most informative measures from existent stroke-examination scales (Toronto Stroke Scale, Oxbury Initial Severity Scale, and Cincinnati Stroke Scale) and creating a composite scale that was further reviewed by a panel of stroke researchers and amended (further items were added to ensure the assessment was as comprehensive as possible). The resulting scale was piloted and refined in a controlled trial of naloxone in acute stroke. It has since been used as primary or coprimary end point in landmark trials of thrombolytic agents and is commonly used in clinical acute-stroke practice.

Using a factor-analysis process, utility of individual components of the NIHSS has been assessed.Citation23 This work has formed the basis for development of the modified NIHSS or mNIHSS, which removed components deemed unreliable.Citation24 The resulting 11-point mNIHSS has been prospectively assessed, and improved reliability is described.Citation25 As the standard NIHSS is already fairly quick to perform and reliable, it is debatable whether a shorter scale is needed, and at present the mNIHSS is not frequently used in trials or practice. Further amendments to the NIHSS have been described to facilitate use of the scale in prehospital settings.Citation26 A pediatric NIHSS (pedNIHSS) is also described.Citation27

The NIHSS has many advantages as a stroke outcome-assessment tool. It is relatively straightforward and takes around 6 minutes to perform, with no need for additional equipment. In the acute-stroke environment, the NIHSS is well suited to serial measures of impairment. It has been suggested that a change in the NIHSS of more than 2 points represents clinically relevant early improvement or deterioration.Citation28

NIHSS scores are reliable across observers, and this has been demonstrated both in cohorts of neurology-trained and non-neurologist raters. The availability of a reliable method for neurological exam that is suitable for nonspecialists is a particular strength of the NIHSS. Reliability and validity has also been demonstrated for remote NIHSS assessment via telemedicine.Citation29 The interobserver reliability of the NIHSS is further improved by the various training materials available. Training resources now exist, such as DVDs and online educational aids, as well as pocket-sized NIHSS summary scales. Practitioners can undergo certification to demonstrate their proficiency in assessment and interpretation of the NIHSS.Citation30

Content validity of the NIHSS has been demonstrated, although high internal consistency suggests that certain items of the NIHSS may be redundant. The NIHSS has predictive validity, as initial score is a robust predictor of in-hospital complication and outcome at 3 months.Citation31,Citation32 Correlations with objective measures of stroke severity, such as size of infarct on imaging, provide further evidence of NIHSS validity.Citation23,Citation33,Citation34 Compared with BI and mRS, the NIHSS is the more sensitive outcome score, requiring potentially smaller sample sizes to detect relevant therapeutic effects.Citation23,Citation35 The NIHSS is responsive to change and can measure impairment throughout the expected range of stroke severity.Citation36

A criticism of the NIHSS relates to its validity in certain nondominant-hemisphere stroke syndromes. It is well recognized that an individual can score 0 on the NIHSS, despite having evidence of ischemic stroke, particularly in the posterior circulation territory.Citation37 Examination of the component subscales of the NIHSS reveals a focus on limb and speech impairments and relatively little attention to, for example, cranial nerve lesions. Similarly, when the NIHSS is used to predict dependent living, lower scores are seen in posterior circulation events compared to anterior circulation.Citation38 There are radiological correlates, when quantifying extent of cerebral damage for a specified NIHSS score, the median volume of right-hemisphere strokes is larger than the volume of left-hemisphere strokes, suggesting nondominant strokes are required to be more severe to reach the same grading on the NIHSS.Citation39 As an impairment scale, the NIHSS can give only limited information on how stroke has affected the individual stroke survivor. For example, an NIHSS score of 1 is considered an “excellent” outcome from stroke; a hemianopia that precludes driving and may necessitate loss of employment would score NIHSS 1, but for the individual this may not seem an “excellent” result.

Barthel Index

Adapted from the Maryland Disability Index, the BI authors – Florence I Mahoney and Dorothea W Barthel – intended their scale for use as “a simple index of independence, useful in scoring improvement in rehabilitation.”Citation40 First described in the 1950s and published in 1965, the BI was developed to assist in discharge planning from long-term care wards. With time, the BI has been adopted by other disciplines and is a recommended assessment in older adult care.Citation41 The BI is the most commonly used functional measure in stroke-rehabilitation settings and the second most commonly used functional outcome measure across stroke trials.Citation16,Citation42 Many scales have been described that take the name “Barthel Index”. Some authors have sought to modify or adapt the BI from the original; these include reducing the number of items,Citation43 extending it with the addition of cognitive and social domains,Citation44 and attempts to further subdivide the outcomes to include different degrees of assistance.Citation45 However, each of these requires independent validation, as it is known that even comparatively minor adaptations alter the validity of a tool and accuracy of responses.Citation46 For consistency, it is recommended that a single BI measure is used; the scale as described by Wade and CollinCitation47 has been used in many trials.

The BI assesses ten functional tasks of daily living (activities of daily living – ADL), scoring the individual depending on independence in each task. Scores range from 0 and 100, with a higher score indicating greater independence (). The BI is usually summed to give a total score. While this can be useful for statistical analysis, it is more informative in practice to present the scores for the individual domains. An unresolved issue for trials is how to define a “good” BI outcome, with significant heterogeneity within the published literatureCitation48 and attempts to subcategorize, based on total score.Citation49,Citation50 A popular interpretation of BI scores is that subjects with BI > 80 are generally independent and should be able to return home; while subjects with BI < 40 are very dependent.Citation51 Other interpretations of favorable and unfavorable BI outcomes have been described: statistical modeling looking at differing BI scores as a trial end point suggested a score of 95/100 was the optimal descriptor of an excellent outcome and that 75/100 was the best cut point for defining a poor outcome.Citation52

Table 1 The Barthel Index of activities of daily living

Validity of BI is well described. The scale is recognized as a valid prognostic tool following stroke, in particular as predictor of recovery, level of care required,Citation53 and duration of rehabilitation required following stroke.Citation54 BI scores correlate with other stroke-assessment scales,Citation55 including other more detailed ADL scales.Citation56 Interobserver reliability is usually quoted as a strength of the BI, and reliability has been demonstrated in nonstroke populations.Citation57 Systematic review of reliability of BI in stroke also suggests reasonable reliability, although few multicenter reliability studies are available.Citation58

The original BI is not without its limitations. As a scale of primarily physical function, it does not reflect the burden on the individual of communication and cognitive deficits that can result from a stroke event.Citation59 For clinical trials, the BI lacks a result to represent stroke mortality, and this can complicate analysis of results. However, the major limitation of the BI for clinical trial use is its responsiveness to change. Although in certain stroke-care settings, the BI is as sensitive to change as other scales,Citation60 a score must be able to represent changes throughout the entire spectrum of potential functional outcomes. It is in this regard that the “foor” and “ceiling” effects of the BI become apparent.Citation50 “Floor and ceiling” describes the phenomenon by which the score does not change from minimum or maximum despite clinical change.Citation61 For example, a stroke patient in a neurointensive care setting can make significant gains but still score a total 0 on the BI; conversely, a patient who is discharged from hospital and independent may still have substantial functional problems but will score 100 on the BI. Given this limitation, the BI may be best suited to stroke survivors requiring inpatient rehabilitation, while other scales may be needed to assess functional change in those with more major or minor stroke symptoms.Citation62

The BI can be considered as a measure of “basic” ADL (self-care and mobility). Scales have been developed to encapsulate performance in more complex tasks. These are variously described as “instrumental” or “extended” activities of daily living (E-ADL) measures.Citation63 The term “instrumental ADL” was first used in Lawton and Brody’s work, and a Lawton I-ADL scale is described.Citation64 A validated measure that has been used with stroke survivors is the Nottingham Extended ADL Scale, which asks participants to reflect their actual activities over the preceding weeks, rather than simply what they have the capability to do.Citation65,Citation66 The Nottingham Extended ADL Scale compares favorably to the BI, and is less susceptible to the ceiling effects described.Citation67

Modified Rankin Scale

The mRS is a 6-point, ordinal hierarchical scale that describes “global disability” with a focus on mobility (). The original Rankin Scale was developed by the Scottish physician John Rankin to describe the positive outcomes he was achieving in his prototypic stroke unit.Citation68 Although not originally intended as an assessment for clinical trials, a slightly modified version of Rankin’s eponymous scale was used as end point in the first multicenter stroke trial (the UK TIA study).Citation69 Since this time, the mRS has grown in popularity and is now the most commonly used functional measure in stroke trials, and has been the primary or coprimary outcome in most recent large-scale stroke trials.Citation16 A further variation of the mRS, the Oxford Handicap Scale, has been described but is not commonly used by trialists. In contemporary stroke studies, the mRS is often used both as a measure of premorbid ability to assist in selection of patients and as final outcome measure.

Table 2 The modified Rankin Scale (mRS)

The mRS has many potential strengths, and it is acceptable to patient and assessor, with nonstandardized interviews taking around 5 minutes to complete.Citation70 Concurrent validity is demonstrated by strong correlation with measures of stroke pathology (for example, infarct volumes) and agreement with other stroke scales.Citation71,Citation72 The six potential scores on the mRS (0–5) describe a full range of stroke outcomes, with a score of 6 usually added to denote death. With a limited number of scores, the mRS may be less responsive to change than some other scales; however, a single-point change on the mRS will always be clinically relevant.

The principle limitation of the mRS is its reliability, with the potential for substantial interobserver variability. A study describing the interobserver variability of the mRS is available; indeed, in the first clinical studies that used the mRS as end point, the trialists described interobserver variability for a third of subjects interviewed by paired assessors.Citation73 A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies describing interobserver variability of the mRS reports pooled reliability across ten published studies (n = 587 patients) of kappa = 0.46.Citation74 Those studies that assessed mRS reliability with multiple raters and centers (ie, similar to a contemporary clinical trial) revealed a worryingly low agreement of kappa = 0.21.Citation75 This level of inconsistency will impact on the validity of the trial results and conclusions. The statistical “noise” created by the interobserver variability will increase the possibility of a type II error, ie, a beneficial treatment effect is missed. It has been postulated that problems with mRS reliability may have partly explained a series of unexpected neutral results in large-scale neuroprotectant studies. There are published examples of nonstroke studies whose results were fundamentally altered when statistical analysis accounted for observer variation.Citation76

Recognizing the problems of reliability in standard mRS assessments, trialists have explored various interventions to improve consistency in scoring. Usual mRS interviews are unstructured, and researchers vary considerably in their length of interview and number of questions asked. More structured approaches to assessment have been described, from a comprehensive scripted interviewCitation75 to use of anchoring questions that require a yes/no answer.Citation77 The groups that developed these assessments describe substantial improvements in reliability. However, improvements have not been seen when the structured interviews have been tested by independent centers.Citation78 Training in use of the mRS can also offer potential to improve consistency. As with the NIHSS and BI, an online training resource is available with an accompanying certification exam.Citation79 A further trial modification that may improve reliability is to record mRS interviews and have a remote consensus grading by experienced stroke trialists. This approach is currently being utilized by a number of multicenter studies.

Two other modifications to mRS assessment are commonly used and deserve some discussion: using proxies to substitute for stroke survivors in the mRS interview and calculating a “prestroke” mRS. Stroke survivors often have physical, language, or cognitive impairments that may complicate a standard face-to-face interview. In this situation, an informant who knows the patient often supplements the interview or substitutes it completely. While this approach makes intuitive sense, we should not assume validity, and clinimetric analysis is still required. A recent systematic review of proxy stroke scales (the mRS was not included) suggested that the properties of certain proxy-based assessments may differ from equivalent standard assessments.Citation80 A study of proxy mRS described suboptimal reliability and validity, and recommended that direct mRS interview with the patient should be the preferred assessment if possible.Citation81 In stroke trials, traditional statistical analyses assess numbers achieving a “good” functional outcome. To improve trial power, subjects with disability prior to the stroke event are often excluded. Assessment of a “prestroke mRS” has been used in many landmark stroke trials, where prestroke mRS > 2 is used as the exclusion criterion during participant selection. The wording of the mRS grades is not suited to such prestroke assessment, and it is perhaps unsurprising that when formally assessed, prestroke mRS had only moderate reliability and validity.Citation82

Quality of life

In view of improving longer-term survival and functional outcomes following stroke,Citation83 it could be argued that assessments against participation or QOL will become increasingly important.Citation84 Certainly evaluations of health-related QOL in stroke survivors can provide a rich description of the multifaceted effects of a stroke, providing insights above those recorded with traditional impairment and activity measures.Citation85 Measuring health-related QOL in stroke presents particular challenges. Important predictors and components of QOL following stroke will vary at different periods following the event.Citation86 Thus, we must balance having a suitably comprehensive assessment that is sensitive to the nuances of QOL against the time and burden required for this assessment. QOL is very much dependent on the individual’s experience of their condition. This poses a particular problem where the stroke survivor has difficulty communicating. Carer/family-based assessments of the patient’s QOL are often biased, with the proxies reporting poorer outcomes than the subject.Citation87

Various QOL scales have been proposed, some generic and some specific to stroke/brain injury. QOL scales should be subject to the same rigor of clinimetric assessment as any other scale. It is evident from the published literature that for QOL there is a propensity to generate new scales rather than validating existing ones.Citation88,Citation89 It has been argued that QOL can be assessed by asking just two questions assessing “dependency” and “problems.”Citation90 An alternative approach is to apply existing health-related QOL scales or to use disease-specific scores. There are strengths and limitations to each approach.

The Short Form 36 (SF-36) is a generic scale intended for patient completion that assesses eight domains of health-related QOL derived from the Medical Outcomes Study ().Citation91 Although the SF-36 is validated for stroke patients,Citation92 noncompletion bias and marked floor and ceiling effects may limit its utility.Citation93,Citation94 The generic QOL scale, Euro-Qol, was developed based on the findings of an international postal survey.Citation95 The self-completion questionnaire requires assessment across five domains complemented by a visual analog scale ().Citation96 EuroQol has been validated in stroke populations.Citation97 However, noncompletion bias is recognized: in one study, only 61% of stroke survivors could complete the scale without external assistance.Citation97 The stroke-specific QOL scale was developed based on interviews with stroke survivors.Citation98 It is based on twelve domains ().Citation93 The scale is validated in stroke populations, and values for “minimal detectable change” and “clinically important difference”Citation99 are established. A modification for those with poststroke aphasia is also described.Citation100

Table 3 Domains assessed in three commonly used quality-of-life scales

Conclusion

Many assessment tools, spanning various functional domains, are available to clinicians and researchers working with stroke survivors. We have given a favor of the marked heterogeneity in use of assessment scales. Lack of consistency in outcome assessment has hindered comparative research and meta-analysis, and so we would recommend that future researchers use a common set of outcome assessments. No perfect stroke-assessment scale exists, and in this review we have deliberately avoided suggestions that one scale is better than an other. We have focused on the three most commonly used stroke scales (mRS, BI, NIHSS) as exemplars. These scales have been validated, are familiar to many, and have proven utility, with each suited to differing assessment scenarios. Thus, in the absence of a “perfect” assessment, we would recommend continuing use of the three core assessment scales: the mRS as an outcome if the study is describing global disability, the NIHSS for studies looking at neurological impairment, and the BI for studies looking at basic ADL. Trialists and clinicians can supplement these core assessments with specific tools suited to the clinical scenario/research question. Increasing awareness of the importance of clinimetric properties has highlighted deficiencies and potential limitations with stroke functional assessment. Clinicians and researchers should always select their assessment tool(s) based on the question of interest and the evidence base around clinimetric properties. Where, as is often the case, the research around clinimetric properties of a scale is sparse, we would encourage researchers to design and conduct their own clinimetric studies.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Stroke Unit Trialists’ CollaborationOrganised inpatient (stroke unit) care for strokeCochrane Database Syst Rev20074CD000197

- WardlawJMMurrayVBergeEdel ZoppoGJThrombolysis for acute ischaemic strokeCochrane Database Syst Rev20094CD000213

- SandercockPAGCounsellCKamalAKAnticoagulants for acute ischaemic strokeCochrane Database Syst Rev20084CD00002418843603

- BathPMWLeesKRABC of arterial and venous disease. Acute strokeBMJ200032092092310742005

- The Internet Stroke CentreStroke assessment scales overview1995 Available from: http://www.strokecenter.org/trials/scales/scales-overview.htmAccessed December 7, 2012

- WadeDTMeasurement in Neurological RehabilitationOxfordOxford University Press1992

- KaneRLAssessing Older Persons: Measures, Meaning and Practical ApplicationsNew YorkOxford University Press2000

- LeesRFearonPHarrisonJKBroomfieldNMQuinnTJCognitive and mood assessment in stroke research: focused review of contemporary studiesStroke2012431678168022535271

- World Health OrganizationTowards a Common Language for Functioning, Disability and HealthGenevaWHO2002 Available from: http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/training/icfbeginnersguide.pdfAccessed December 7, 2012

- FeinsteinARAn additional basic science for clinical medicine: IV. The development of clinimetricsAnn Intern Med1983998438486651026

- AsplundKClinimetrics in stroke researchStroke1987185285303564114

- FavaGATombaESoninoNClinimetrics: the science of clinical measurementsInt J Clin Pract201266111522171900

- LandisJRKochGGThe measurement of observer agreement for categorical dataBiometrics197733159174843571

- KraemerHCBlochDAKappa coefficients in epidemiology: an appraisal of a reappraisalJ Clin Epidemiol19884159683335870

- BlandJMAltmanDGMeasuring agreement in method comparison studiesStat Methods Med Res1999813516010501650

- QuinnTJDawsonJWaltersMRLeesKRFunctional outcome measures in contemporary stroke trialsInt J Stroke2009420020519659822

- Turner-StokesLMeasurement of outcome in rehabilitation: the British Society of Rehabilitation Medicine “basket” of measures. 2000 Available from: http://www.bsrm.co.uk/ClinicalGuidance/OutcomeMeasuresB3.pdfAccessed December 7, 2012

- Optimising Analysis of Stroke Trials (OAST) CollaborationBathPMGrayLJCollierTPocockSCarpenterJCan we improve the statistical analysis of stroke trials? Statistical reanalysis of functional outcome in stroke trials. The optimising analysis of stroke trials (OAST) collaborationStroke2007381911191517463316

- SaverJLGornbeinJTreatment effects for which shift or binary analyses are advantageous in acute stroke trialsNeurology2009721310131519092107

- Popa-WagnerAStöckerKBalseanuATEffects of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor after stroke in aged ratsStroke2010411027103120360546

- SchaarKLBrennemanMMSavitzSIFunctional assessments in the rodent stroke modelExp Transl Stroke Med201021320642841

- BrottTAdamsHPOlingerCPMeasurements of acute cerebral infarction: a clinical examination scaleStroke1989208648702749846

- LydenPLuMJacksonCUnderlying structure of the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale: results of a factor analysis: NINDS tPA Stroke Trial InvestigatorsStroke1999302347235410548669

- LydenPDLuMLevineSRBrottTGBroderickJA modified National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale for use in stroke clinical trials: preliminary reliability and validityStroke2001321310131711387492

- MeyerBCHenmenTMJacksonCMLydenPDModified National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale for use in stroke clinical trials: prospective reliability and validityStroke2002331261126611988601

- TirschwellDLLongstrethWTBeckerKJShortening the NIHSS for use in the prehospital settingStroke2002332801280612468773

- IchordRNBastianRAbrahamLInterrater reliability of the Pediatric National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (PedNIHSS) in a multicenter studyStroke20114261361721317270

- AdamsHPDavisPHLeiraECBaseline NIH stroke scale strongly predicts outcome after stroke: a report of the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST)Neurology19995312613110408548

- MeyerBCRamanRChaconMRJensenMWernerJDReliability of site-independent telemedicine when assessed by telemedicine-naïve stroke practitionersJ Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis20081718118618589337

- LydenPRamanRLiuLEmrMWarrenMMarlerJNational Institutes of Health Stroke Scale certification is reliable across multiple venuesStroke2009402507251119520998

- BooneMChillonJMGarciaPYNIHSS and acute complications after anterior and posterior circulation strokesTher Clin Risk Manag20128879322399853

- JohnstonKCWagnerDPRelationship between 3-month National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score and dependence in ischemic stroke patientsNeuroepidemiology2006279610016926554

- MuirKWWeirCJMurrayGDPoveyCLeesKRComparison of neurological scales and scoring systems for acute stroke prognosisStroke199627181718208841337

- AdamsHPJrBendixenBHLeiraEAntithrombotic treatment of ischemic stroke among patients with occlusion or severe stenosis of the internal carotid artery: a report of the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST)Neurology19995312212510408547

- YoungFBWeirCJLeesKRGAIN International Trial Steering Committee and InvestigatorsComparison of the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale with disability outcome measures in acute stroke trialsStroke2005362187219216179579

- LindsellCJAlwellKMoomawCJValidity of a retrospective National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale scoring methodology in patients with severe strokeJ Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis200514628128317904038

- Martin-SchildSAlbrightKCTanksleyJZero in the NIHSS does not equal the absence of strokeAnn Emerg Med201157424520828876

- SatoSToyodaKUeharaTBaseline NIH Stroke Scale Score predicting outcome in anterior and posterior circulation strokesNeurology2008702371237718434640

- WooDBroderickJPKothariRUDoes the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale favor left hemisphere strokes? Stroke1999302355235910548670

- MahoneyFIBarthelDFunctional evaluation: the Barthel IndexMd State Med J1965145661

- Royal College of Physicians EnglandStandardised Assessment Scales for Elderly People Report of the Joint Workshops of the Research Unit of the Royal College of Physicians of London and the British Geriatric SocietyLondonRoyal College of Physicians1992

- SanghaHLipsonDFoleyNA comparison of the Barthel Index and the Functional Independence Measure as outcome measures in stroke rehabilitation: patterns of disability scale usage in clinical trialsInt J Rehabil Res20052813513915900183

- HobartJCThompsonAJThe five item Barthel indexJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry20017122523011459898

- ProsiegelMBottgerSSchenkTDer Erwertiertr Barthel Index (EBI)-eine neue Skala zur Erfassung von Fahigkeitsstorungen bei neurologischen patieneten. [The extended Barthel Index a new scale for assessment of functional ability in neurological patients]Neurol Rehabil19961713

- ShahSVanclayFCooperBImproving the sensitivity of the Barthel Index for stroke rehabilitationJ Clin Epidemiol1989427037092760661

- PicavetHSvan den BosGAComparing survey data on functional disability: the impact of some methodological differencesJ Epidemiol Community Health19965086938762361

- WadeDTCollinCThe Barthel ADL Index: a standard measure of physical disabilityInt Disabil Stud19881064673042746

- SulterGSteenCDe KeyserJUse of the Barthel Index and Modified Rankin Scale in acute stroke trialsStroke1999301538154110436097

- NakaoSTakataSUemuraHRelationship between Barthel Index scores during the acute phase of rehabilitation and subsequent ADL in stroke patientsJ Med Invest201057818820299746

- BaluSDifferences in psychometric properties, cut-off scores, and outcomes between the Barthel index and modified Rankin Scale in pharmacotherapy-based stroke trials: systematic literature reviewCurr Med Res Opin2009251329134119419341

- SinoffGOreLThe Barthel activities of daily living index: self-reporting versus actual performance in the old-old (> or = 75 years)J Am Geriatr Soc1997458328369215334

- UyttenboogaartMStewartREVroomenPCDe KeyserJLuijckxGJOptimizing cutoff scores for the Barthel index and the modified Rankin scale for defining outcome in acute stroke trialsStroke2005361984198716081854

- HuybrechtsKFCaroJJThe Barthel Index and modified Rankin Scale as prognostic tools for long term outcomes after stroke: a qualitative review of the literatureCur Med Res Opin20072316271636

- CohenMEMarinoRJThe tools of disability outcomes research functional status measuresArch Phys Med Rehabil200081Suppl 2S21S2911128901

- GrangerCVAlbrechtGLHamiltonBBOutcome of comprehensive medical rehabilitation: measurement by PULSES Profile and Barthel IndexArch Phys Med Rehabil197960145154157729

- HobartJCLampingDLFreemanJAEvidence-based measurement: which disability scale for neurologic rehabilitation? Neurology20015763964411524472

- SainsburyAGudrunSBansalAYoungJBReliability of the Barthel Index when used with older peopleAge Ageing20053422823215863408

- DuffyLGajreeSLanghornePStottDJQuinnTJReliability of Barthel Index in stroke – systematic review and meta-analysisStroke2012 In press

- NovakSJohnsonJGreenwoodRBarthel revisited: making guidelines workClin Rehabil199610128134

- DromerickAWEdwardsDFDiringerMNSensitivity to changes in disability after stroke: comparison of four scales useful in clinical trialsJ Rehabil Res Dev2003401815150715

- SchepersVPKetelaarMVisser-MeilyJMDekkerJLindemanEResponsiveness of functional health status measures frequently used in stroke researchDisabil Rehabil2006281035104016950733

- WeimarCKurthTKraywinkelKAssessment of Functioning and disability after ischemic strokeStroke2002332053205912154262

- ChongDKMeasurement of instrumental activities of daily living in strokeStroke199526111911227762032

- LawtonMPBrodyEMAssessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily livingGerontologist196991791865349366

- NouriFMLincolnNBAn extended ADL scale for use with stroke patientsClin Rehabil19871301305

- GladmanJRFLincolnNBAdamsSAUse of the extended ADL scale in stroke patientsAge Ageing1993224194248310887

- SarkerSJRuddAGDouiriAWolfeCDComparison of 2 extended activities of daily living scales with the Barthel Index and predictors of their outcomes: cohort study within the South London Stroke Register (SLSR)Stroke2012431362136922461336

- QuinnTJDawsonJWaltersMDr John Rankin; his life, legacy and the 50th anniversary of the Rankin Stroke ScaleScot Med J200853444718422210

- FarrellBGodwinJRichardsSWarlowCThe United Kingdom transient ischaemic attack (UK-TIA) aspirin trial: final resultsJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry199154104410541783914

- QuinnTJMcArthurKDawsonJWaltersMRLeesKRReliability of structured modified Rankin Scale assessmentStroke201041602603

- SchiemanckSKPostMWMKwakkelGIschaemic lesion volume correlates with long term functional outcome and quality of life of middle cerebral artery stroke survivorsRestor Neurol Neurosci20052325726316082082

- BanksJLMarottaCAOutcomes validity and reliability of the modified Rankin Scale: implications for stroke clinical trials: a literature review and synthesisStroke2007381091109617272767

- Van SwietenJCKoudstaalPJVisserMCSchoutenHJAvan GijnJInter-observer agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patientsStroke1988196046073363593

- QuinnTJDawsonJWaltersMRLeesKRReliability of the modified Rankin Scale: a systematic reviewStroke2009403393339519679846

- WilsonJTLHareendranAHendryAPotterJBoneIMuirKWReliability of the modified Rankin Scale across multiple raters: benefts of a structured interviewStroke20053677778115718510

- JaffarSLeachASmithPGCuttsFGreenwoodBEffects of misclassification of causes of death on the power of a trial to assess the efficacy of a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in the GambiaInt J Epidemiol20033243043612777432

- SaverJLFilipBYanesAImproving the reliability of stroke disability grading in clinical trials and clinical practice: the Rankin Focussed AssessmentStroke2010599299520360551

- QuinnTJDawsonJWaltersMRLeesKRExploring the reliability of the modified Rankin ScaleStroke20094076276619131664

- QuinnTJDawsonJLeesKRHardemarkHGWaltersMRInitial experience of a digital training resource for modified Rankin Scale assessment in clinical trialsStroke2007382257226117600236

- OczkowskiCO’DonnellMReliability of proxy respondents for patients with stroke: a systematic reviewJ Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis2010541041620554222

- McArthurKBeaganMLCDegnanAProperties of proxy-derived modified Rankin Scale assessmentInt J Stroke Epub February 15, 2012

- FearonPMcArthurKSGarrityKPre-stroke modified Rankin Stroke Scale has moderate inter-observer reliability and validity in an acute stroke settingsStroke2012438488

- LanghornePWrightFStottDImproved survival after strokeCerebrovasc Dis20072332032117215577

- Carod-ArtalFJEgidoJAQuality of life after stroke: the importance of a good recoveryCerebrovascular Dis200927Suppl 1204214

- PatelMDTillingKLawrenceERuddAGWolfeCDAMcKevittCRelationships between long-term stroke disability, handicap and health-related quality of lifeAge Ageing20063527327916638767

- PatelMDMcKevittCLawrenceERuddAGWolfeDAClinical determinants of long-term quality of life after strokeAge Ageing20073631632217374601

- WilliamsLSBakasTBrizendineEHow valid are family proxy assessments of stroke patients’ health-related quality of life? Stroke2006372081208516809575

- De HaanRAaronsonNLimburgMHewerRLvan CrevelHMeasuring quality of life in strokeStroke1993243203278421836

- TengsTOYuMLuistroEHealth-related quality of life after stroke a comprehensive reviewStroke20013296497211283398

- DormanPDennisMSandercockPAre the modified “simple questions” a valid and reliable measure of health related quality of life after stroke? United Kingdom Collaborators in the International Stroke TrialJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry20006948749310990509

- WareJESF-36 health survey updateSpine (Phila Pa 1976)2000253130313911124729

- AndersonCLaubscherSBurnsRValidation of the Short Form 36 (SF-36) health survey questionnaire among stroke patientsStroke199627181218168841336

- O’MahonyPGRodgersHThomsonRGDobsonRJamesOFWIs the SF-36 suitable for assessing health status of older stroke patients? Age Ageing19982719229504362

- HobartJCWilliamsLSMoranKThompsonAJQuality of life measurement after stroke: uses and abuses of the SF-36Stroke2002331348135611988614

- [No authors listed.]EuroQol – a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. The EuroQol GroupHealth Policy19901619920810109801

- BrooksREuroQol: the current state of playHealth Policy199637537210158943

- DormanPJWaddellFSlatteryJDennisMSandercockPIs the EuroQol a valid measure of health-related quality of life after stroke? Stroke199728187618829341688

- WilliamsLSWeinbergerMHarrisLEClarkDOBillerJDevelopment of a stroke-specific quality of life scaleStroke1999301362136910390308

- LinKCFuTWuCYHsiehCJAssessing the stroke-specific quality of life for outcome measurement in stroke rehabilitation: minimal detectable change and clinically important differenceHealth Qual Life Outcomes20119521247433

- HilariKByngSMeasuring quality of life in people with aphasia: the Stroke Specific Quality of Life ScaleInt J Lang Commun Disord200136Suppl869111340850