Abstract

COPD is accompanied by limited physical activity, worse quality of life, and increased prevalence of depression. A possible link between COPD and depression may be irisin, a myokine, expression of which in the skeletal muscle and brain positively correlates with physical activity. Irisin enhances the synthesis of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a neurotrophin involved in reward-related processes. Thus, we hypothesized that mood disturbances accompanying COPD are reflected by the changes in the irisin–BDNF axis. Case history, routine laboratory parameters, serum irisin and BDNF levels, pulmonary function, and disease-specific quality of life, measured by St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ), were determined in a cohort of COPD patients (n=74). Simple and then multiple linear regression were used to evaluate the data. We found that mood disturbances are associated with lower serum irisin levels (SGRQ’s Impacts score and reciprocal of irisin showed a strong positive association; β: 419.97; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 204.31, 635.63; P<0.001). This association was even stronger among patients in the lower 50% of BDNF levels (β: 434.11; 95% CI: 166.17, 702.05; P=0.002), while it became weaker for patients in the higher 50% of BDNF concentrations (β: 373.49; 95% CI: −74.91, 821.88; P=0.1). These results suggest that irisin exerts beneficial effect on mood in COPD patients, possibly by inducing the expression of BDNF in brain areas associated with reward-related processes involved in by depression. Future interventional studies targeting the irisin–BDNF axis (eg, endurance training) are needed to further support this notion.

Keywords:

Introduction

COPD, by profoundly impacting the patient’s quality of life, poses great socio-economic burden for individual patients, their families, and society.Citation1,Citation2 COPD primarily worsens quality of life by developing chronic, progressive dyspnea and consequent limitation of physical activity.Citation3 Moreover, co-existing mental health problems show higher prevalence in COPD patients than in the general population,Citation2,Citation4 with depression and anxiety being present in ~20%–40% and 30%–50% of COPD cases, respectively.Citation2,Citation4–Citation7 Disturbance of mood not only causes disability per se but also changes the course of the disease by altering how patients experience and manage their disease, thus worsening their functional and health status.Citation4,Citation8 Therefore, the quest to elucidate the potential mechanisms underlying mood disturbances in COPD is ever so pressing.

Irisin is a recently identified putative contraction-regulated myokine that is formed by proteolytic cleavage of transmembrane fibronectin type III domain-containing protein 5 (FNDC5).Citation9 Expression of FNDC5 was shown to positively correlate with physical activity in several organs (eg, skeletal muscle and brain) as its increased or decreased expression was observed in response to sustained physical training or sedentary lifestyle, respectively.Citation10–Citation12 It is interesting that FNDC5 expression has been shown in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and hippocampus,Citation13 structures serving model-free and model-based reward-related reinforcement learning processes.Citation14,Citation15 Irisin, the highly conserved fragment of FNDC5, is released into the systemic circulation to exert its most established effect of inducing white adipose tissue browning, activating oxygen consumption, and thermogenesis of fat cells.Citation9,Citation16 In addition, irisin may cross the blood–brain barrier to exert its influence in the central nervous system.Citation17 Recently, based on preclinical models and clinical evidence, our group has proposed that irisin, by inducing brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression in VTA and hippocampus, may serve as a link between physical activity and reward-related learning and motivation.Citation18 BDNF, a neurotrophin, has been associated with reward-related learning and consequent alteration of behavior.Citation19 BDNF and its high-affinity receptor tropomyosin-related kinase B are also expressed in the midbrain and hippocampus.Citation12,Citation20,Citation21

Motivation and allied reward-related processes are often conceptualized using the reinforcement learning theorem, tied closely to the mesocortico-limbic system.Citation14,Citation15,Citation22 Several disorders have been mapped onto the reinforcement learning paradigm including depression, with distinct attributes of value-based decision-making being altered. For example, higher discounting rates for delayed rewards reflective of hopelessness and unwillingness to invest in the future were shown in major depressive disorder.Citation23 In a different study, anhedonia, one of the cardinal symptoms of major depressive disorder, was associated with diminished primary sensitivity to rewards.Citation24 Accordingly, the dysfunction of VTA–ventral striatum axis has been specifically associated with anhedonia and anergy, also characteristic of depression.Citation25

Summarizing, it may be proposed that change of reward processing in mood disorders may be accompanied by alteration in the irisin–BDNF axis. Starting from this hypothesis, we set out to investigate the significant predictors of mood disturbance, with a special focus on the role serum irisin and BDNF play in a cohort of patients suffering from COPD, a disease associated with mental health problems including depressive symptoms.

Methods

Study design and protocol

This study was designed in agreement with the STROBE statement for cross-sectional studiesCitation26 and is in line with the principles established by the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval of the Ethical Committee of the University of Debrecen (DEOEC RKEB/IKEB 3632-2012) was obtained in advance. Informed written consent was obtained from each participant.

In this study, data of our COPD cohort (described previouslyCitation27) have been further analyzed. Briefly, every COPD patient, attending the outpatient unit of the Department of Pulmonology (University of Debrecen) between September 1, 2012 and October 15, 2013, for the management of COPD, was screened by attending pulmonologists, who were unaware of the research hypothesis and study protocol. Patients suffering from any acute inflammatory disease over the preceding 1 month and those having benign or malignant tumors in their case history were excluded. Patients meeting the entry criteria were referred to the study nurse who explained the details of the study and obtained informed consent. Every patient referred by the pulmonologists consented to study participation. Overall, 74 COPD patients were recruited. At the time of inclusion, patients were managed for COPD according to the relevant Hungarian practice guidelineCitation28 and the GOLD initiative.Citation29 Airway limitation was defined using the lower limit of normal.Citation30–Citation32 Patients received therapy at the time of inclusion as clinically warranted. Whole-body plethysmography was performed for every patient to obtain lung function parameters. Demographic, anthropometric, anamnestic, laboratory, and quality of life data were also acquired. Cumulative measure of smoking exposure was described by pack-years (accounted for both past and current smoking exposure). To assess disease-specific quality of life, the official Hungarian version of Saint George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ)Citation33 was used with the permission of the proprietor (Paul Jones, University of London, London, UK).

Pulmonary function testing

Whole-body plethysmography was performed according to the ATS/ERS criteriaCitation34,Citation35 with Piston whole-body plethysmograph (PDT-111/p; Piston Medical, Budapest, Hungary) equipped with automatic body temperature- and pressure-saturated correction, furthermore, with full automatic calibration and leakage test. Plethysmography was performed while patients were receiving long-term therapy for COPD. The best of three technically sound maneuvers was selected in case of each participant. Regarding resistance curves, at least two separate and technically appropriate measurements were performed (each measurement consists of recordings of at least five resistance loops) and results were accepted only if these were the same for both measurements. Of the lung function parameters provided by the whole-body plethysmography, the following data proved to be interesting in this study: airway resistance (Raw), forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), FEV1 as a percent of predicted value (FEV1% pred), forced vital capacity (FVC) as a percent of predicted value (FVC% pred), forced expiratory flow between 25% and 75% of FVC (FEF25%–75%), FEF25%–75% as a percent of predicted value (FEF25%–75% % pred), residual volume (RV) as a percent of predicted value (RV% pred), ratio of RV to total lung capacity (TLC) as a percent of predicted value (RV/TLC% pred). For the statistical analysis, parameters showing Gaussian distribution were used in their raw forms, whereas those not normally distributed were appropriately transformed to obtain normal distribution.

Blood samples and routine laboratory tests

Blood samples were obtained in the morning of the examination, after an overnight fast. Routine laboratory investigations were performed by the Department of Laboratory Medicine (University of Debrecen) following their standard procedures. Serum or plasma samples were used to characterize carbohydrate homeostasis (glucose, insulin, hemoglobin A1c [HgA1c]), lipid homeostasis (total cholesterol, triglyceride, low-density lipoprotein [LDL] cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein [HDL] cholesterol, lipoprotein (a), apolipoprotein A1 [ApoA1], apolipoprotein B [ApoB], kidney function (glomerular filtration rate [GFR], urea, creatinine), liver function (glutamate-oxaloacetate transaminase, glutamate-pyruvate transaminase, gamma-glutamyltransferase), status of skeletal muscles (creatine kinase [CK], lactate dehydrogenase), thyroid-stimulating hormone-sensitive (sTSH), and systemic inflammation (C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, and fibrinogen). From glucose and insulin concentrations, homeostatic model assessment (HOMA) index was calculated as described previously.Citation36 Serum samples used to determine irisin and BDNF were frozen within 60 minutes and stored at −80°C until further analysis.

Determination of serum irisin and BDNF

Serum BDNF levels were measured compliant with the manufacturer’s instructions (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). In short, standards and samples (diluted 100-fold) were administered into 96-well microplates coated with anti-BDNF monoclonal antibody and incubated overnight at 4°C. Next, plates were washed four times, and then 100 µL biotinylated anti-human BDNF detector antibody was added to each well and incubated with gentle shaking for 1 hour. Afterwards, the wells were washed and 100 µL of horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-streptavidin solution was added to each well, followed by a 45-minute long incubation period at room temperature with gentle shaking. Samples were washed again, and then 100 µL TMB (3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine) One-Step Substrate Reagent was added to each well and incubation was undertaken for 30 minutes to induce a color reaction. The reaction was stopped with manufacturer-supplied stop solution. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured immediately with an automated microplate reader. All measurements were performed in duplicate. The detection limit for BDNF was <80 pg/mL.

Serum irisin levels were assayed according to the manufacturer’s instructions using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Burlingame, CA, USA). Briefly, 50 µL of standard or sample (diluted two times), 25 µL primary antibody, and 25 µL biotinylated peptide were added to each well, followed by a 2-hour long incubation period at room temperature. The plates were then washed four times and 100 µL/well SA-HRP solution was added and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour. After washing, 100 µL/well of substrate solution was added followed by incubation for 1 hour, after which the reaction was terminated with 100 µL/well of 2 N HCl. Absorbance was read immediately at 450 nm. According to the manufacturer, the irisin standard curve was linear from 1.34 to 29.0 ng/mL, and the detection limit was 1.34 ng/mL.

A standard curve showing linear relationship between optical density and concentration of irisin as well as BDNF was obtained with each plate. For the stratification of the final multiple regression model, serum BDNF levels were dichotomized according to their median value.

St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire

The official Hungarian version of SGRQ validated for a 1-month recall period was used according to the SGRQ manual supplied by the proprietor.Citation37 SGRQ quantifies health impairment with three-component scores and one total score. The Symptoms score characterizes the patients’ perception of their recent respiratory problems in terms of their effect, frequency, and severity; Activity score quantifies the impairment in daily physical activity; whereas the Impacts score characterizes a wide array of disturbances related to the psychosocial function. Importantly, Impacts score also strongly correlates with disturbances of mood (eg, depression). The Total score sums up the significance of the disease on overall health status. Scores are provided as a percentage, thus 100% indicates the worst and 0% represents the best subjective health status. Differences in scores were considered clinically meaningful if they exceeded 4 percent points.Citation38 Patients filled out the questionnaire by means of supervised self-administration. Two independent raters recorded data by diligently following data entry guidelines, and scoring was done using the score calculation algorithm provided by the developer of the SGRQ.Citation39 Inter-rater variability assessed by Spearman correlation was 0.99 (P<0.001), 0.988 (P<0.001), 0.999 (P<0.001), and 0.999 (P<0.001) for the Symptoms, Activity, Impacts, and Total scores of SGRQ, respectively. Both raters were blinded to patients’ irisin and BDNF levels. For statistical analysis (and data presentation), the mean of scores was computed.

Statistical analysis

Disturbances of mood were quantified with the Impacts score reflective of mood disorders and overall psycho-social dysfunction.

The mean of the Impacts score was used as cutoff for dichotomization of the COPD cohort, so patients with Impacts score <32.65% were put into the lower Impacts score group (n=40), while patients with Impacts score ≥32.65% formed the higher Impacts score group (n=34), corresponding to less or more pronounced mood disturbances, respectively.

Normality of continuous variables was checked by the Shapiro–Wilk test. For variables following Gaussian distribution, two data sets were compared using Student’s t-test, whereas Mann–Whitney U-test was carried out for those not showing normal distribution. Frequencies were compared with Pearson’s χ2 test.

The correlation of mood disturbance and serum irisin concentration was established using Spearman’s correlation. The relationship between mood disturbance and serum irisin level was further investigated with simple as well as multiple linear regression. To ensure normal distribution of variables for these analyses, CK, total cholesterol, triglyceride, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, ApoA1, ApoB, insulin, HgA1c, sTSH, HOMA index, FEF25%–75%, RV, and RV% pred were log-transformed; furthermore, square root of disease duration, reciprocal of irisin, and reciprocal of square of glucose concentration were computed.

Simple linear regression was carried out with traditional confounding factors (age, gender, height, and disease duration in years), lung function parameters, and routine laboratory parameters obtained from the serum or plasma samples. Missing data were omitted. To eliminate the effects of potential con-founders, multiple linear regression modeling was performed. First, the least parsimonious multiple model was compiled including all significant regressors identified by means of simple linear regression and a priori variables (age and gender). Variables were introduced into the initial multiple model simultaneously, and then factors not contributing significantly to the model were deleted (except for the a priori variables). The final model contained (in addition to the a priori parameters) FEV1% pred, body mass index, weight, and (log) triglyceride levels. Furthermore, the final model was stratified with respect to BDNF levels. Heteroskedasticity and goodness of fit for the model were assessed by Cook–Weisberg and Ramsey test.

Statistical analysis was performed with Stata 13.0 software StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP). Values are given as mean ± SD or median (with the interquartile range: IQR), and regression coefficients are presented with their 95% confidence interval (95% CI).

Results

Patients

The baseline characteristics of our COPD patient cohort were detailed previously.Citation27 Demographic, anthropometric characteristics, medication history, pulmonary function, and disease-specific health impairment measures are summarized in .

Table 1 Main characteristics of the whole COPD cohort (n=74)

Comparison of patients with respect to mood disturbance

The two groups of COPD patients, dichotomized with respect to the mean of Impacts score, proved to be homogeneous regarding most of the parameters investigated. Nevertheless, in the group with higher Impacts score (showing more pronounced impairment of mood), dyslipidemia, and hypertension (as anamnestic data) were more frequent; serum LDL cholesterol, serum irisin, FEV1% pred, and FVC% pred were significantly lower; whereas serum glucose was significantly higher than the corresponding values in the group with lower Impacts score (showing less despair) ().

Table 2 Main characteristics of two groups of the COPD cohort dichotomized according to mood disturbances indicated by the Impacts score

Associations among SGRQ’s Impacts score, serum irisin, and BDNF levels

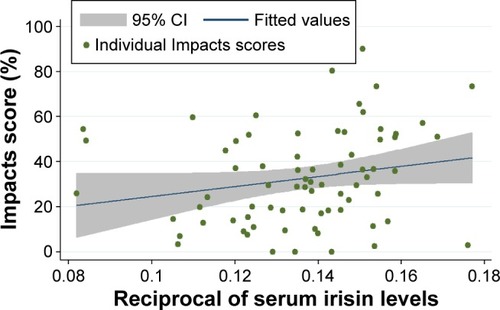

Upon assessing the correlation between the Impacts score and reciprocal of irisin, we found a significant positive correlation in the whole COPD cohort (Spearman correlation coefficient: 0.26, P=0.02; ), in agreement with the finding that irisin concentration was smaller in the higher Impacts score group (). This correlation became stronger (and remained almost statistically significant) in the stratum with lower BDNF level, while it was weaker (and non-significant) in the stratum with higher BDNF (Spearman correlation coefficient: 0.32 and 0.22, P=0.055 and 0.19, respectively).

Figure 1 Correlation of mood disturbance (characterized by the Impacts score of SGRQ) and reciprocal of serum irisin concentration in the whole data set (n=74).

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; SGRQ, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire.

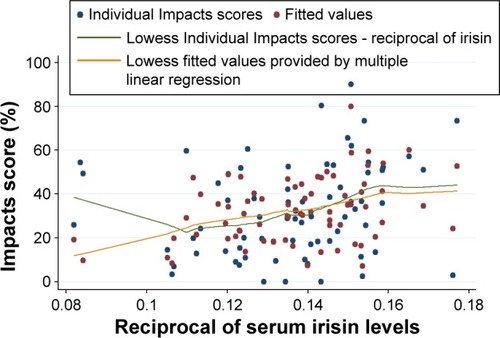

When the relationship between the Impacts score and reciprocal of serum irisin level was analyzed with simple linear regression, the regression coefficient failed to reach statistical significance (P=0.08; ). However, after adjusting for all significant predictors and a priori determinants by means of multiple linear regression, the Impacts score and reciprocal of irisin showed a strong, significant, positive association (β: 419.97; 95% CI: 204.31, 635.63; P<0.001) (). This association became even more distinct among patients with lower BDNF levels (β: 434.11; 95% CI: 166.17, 702.05; P=0.002), while a considerably weaker and statistically nonsignificant association was present in case of patients with higher BDNF concentrations (β: 373.49; 95% CI: −74.91, 821.88; P=0.10). All three models were significant (P<0.001, 0.001, and 0.009) (). The Cook–Weisberg test showed no heteroskedasticity for the full model and strata with lower and higher BDNF (P=0.92, 0.67, and 0.82, respectively). Furthermore, all three models showed good fit reflected by the locally weighted scatterplot smoothing () as well as by the Ramsey test (P=0.82; 0.53, and 0.79 for the whole data set and strata with lower and higher BDNF, respectively).

Table 3 Significant predictors of reciprocal of serum irisin level and Impacts score of SGRQ determined with simple linear regression for the whole COPD cohort (n=74)

Table 4 Multiple linear regression model for the SGRQ’s Impacts score of the whole COPD cohort and its strata with respect to the median BDNF level

Table 5 ANOVA tables describing the final model for the whole cohort (Panel A), lower BDNF stratum (Panel B), and higher BDNF stratum (Panel C)

Figure 2 The model describing the correlation between the Impacts score of SGRQ and reciprocal of serum irisin concentration in the whole data set (n=74).

Abbreviation: SGRQ, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire.

Based on the final multiple linear regression model (built for the Impacts score), body mass index, log triglyceride, and body weight were significantly associated with mood disturbances among COPD patients. In addition, severity of airflow limitation, characterized by FEV1% pred, showed a significant negative association with the Impacts score (β: −0.52; 95% CI: −0.71, −0.32; P<0.001) ().

Discussion

The main finding of this study is that the reciprocal of serum irisin level shows significant positive correlation with the Impacts score of SGRQ in COPD patients. Thus, more pronounced disturbance of mood (indicated by higher Impacts score) is accompanied by lower irisin levels. This effect has proven even more prominent among patients with lower BDNF levels, but became nonsignificant in patients possessing higher BDNF concentrations. Analysis by means of multiple linear regression that corrects for possible con-founders has confirmed the significant association between Impacts score and serum irisin; furthermore, it also revealed four other significant determinants of Impacts score: BMI, weight, triglyceride level, and FEV1% pred, an index of the severity of airflow limitation in COPD.Citation29

Several studies have corroborating evidence for the relationship between markers of disease severity and BMI. Recently, the COPD Gene investigators analyzed the data of 3,631 spirometry-confirmed COPD patients obtained from a multicenter prospective cohort study. The investigators found significant association between obesity, characterized by higher BMI and worse outcomes including poorer quality of life, dyspnea, and reduced 6-minute walk distance. Furthermore, greater odds for acute exacerbations were observed, independent of the presence of comorbidities.Citation40 Furthermore, Ho et alCitation41 have also reported significant correlation between FEV1% (FEV1/FVC) and BMI (Spearman’s correlation coefficient 0.255, P<0.01). In another study, the influence of metabolic syndrome and its components on the 5-year mortality was assessed in COPD. The authors found that 100 mg/dL increase of plasma triglyceride concentration increases the probability of death over the 5 years by 39% (translating into a hazard ratio of 1.39, 95% CI: 1.06, 1.83).Citation42 This finding corroborates our result that log triglyceride levels were significantly associated with the Impacts score in our final multiple linear regression model (). Moreover, the possibility for a common pathomechanism of COPD and depressive disorders was also suggested based on the results of an interventional study. Patients were enrolled in a complex exercise program (2 hours per day, 5 days per week, for 6 weeks) supervised by physiotherapists and lung specialists. At follow-up, improvement of depressive symptoms paralleled by significant reduction of BMI was reported in the subgroup of patients showing signs of depression at baseline.Citation43 These findings could be explained by our proposition that exercise-induced increase in irisin levels may simultaneously induce white adipocyte browning and consequent weight loss and enhance mood via activation of the BDNF pathway in specific brain areas (eg, hippocampus, VTA) involved in affective disorders.

Prognostic value of FEV1% pred regarding population-level clinical outcomes is acknowledged by the Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (2017 report).Citation44 FEV1% pred is also predictive of health status and the rate of exacerbations in COPD and it is closely interconnected with alteration of mood and psychosocial function.Citation30 The significant inverse relationship between Impacts score and FEV1% pred is also in line with previous findings. Significant negative correlation between FEV1% pred and all components (Symptoms, Impacts, Activity) and the total score of SGRQ was previously described in a cohort of Hispanic smokers.Citation45 Similarly, in another study, significant negative correlation between FEV1% pred and the Total score was described in a sample of severe COPD patients (r=−0.4, P<0.001).Citation46 In a double-blind placebo-controlled study designed to assess the benefits of the fixed combination inhaler fluticasone propionate and salmeterol versus placebo, the longitudinal analysis of data for 4,951 COPD patients showed significant negative correlation regarding the change in SGRQ scores and FEV1 during the 3 years of the study in all treatment arms, combined.Citation47 Previously, we also found a significant negative correlation between the Total SGRQ score and FEV1% pred.Citation27

Our present analysis showed a very strong positive association between the Impacts score, reflective of depressive mood disturbances in COPD and the reciprocal of serum irisin () that was substantially more remarkable in the stratum with BDNF levels lower than the sample median. In addition to reciprocal of irisin, regression coefficients remained significant for FEV1% pred, BMI, and log triglyceride in the stratum with lower BDNF levels. However, only FEV1% pred, BMI, and weight showed significant contribution to the final model in the stratum with higher BDNF levels (). These results suggest the presence of an interaction between serum irisin and serum BDNF levels regarding their influence on Impacts score and they underscore our previous hypothesis that serum irisin may exert a peripheral effect reflected by the alteration of metabolic parameters (BMI, weight, and serum triglyceride levels) and a central effect related to mood and motivation based on BDNF’s action.

The role of BDNF in depressive disorders has been articulated by the neurotrophic hypothesis of depression. According to this, depression is based on neurotrophin deficiency of the limbic system, an effect that may be reversed by long-term administration of antidepressants.Citation48,Citation49 This hypothesis is closely linked to the neural plasticity hypothesis, which postulates that environmental factors (eg, stress) cause dysfunction of signal transduction cascades involved in neuronal adaptation and plasticity. A candidate pathway is that containing BDNF-cAMP response element-binding protein, a transcription factor.Citation49

Changes in BDNF plasma levels as well as tissue levels from postmortem biopsies of hippocampus have been described in depressed patients.Citation49 Furthermore, the cause–effect relationship between BDNF and major depressive disorder was established by a case–control study nested in a cohort of 1,276 women aged 75–84 years. Using incident cases and controls over the 4-year observation period, the authors concluded that BDNF is a state marker of major depressive disease based on the longitudinal decrease of serum BDNF levels in this cohort.Citation50 Corroborating evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis of 20 publications including 1,504 participants, furthermore, showed significant correlation between changes of BDNF level and depression score as well as significant increases of BDNF levels accompanied therapy with antidepressants.Citation51 Nevertheless, it should be noted that, despite the accumulating preclinical and clinical evidence, there are some controversies related to the role BDNF plays in the evolution of depression, as inconsistent observations questioning this hypothesis were also reported.Citation52,Citation53 However, these discrepancies may stem from the methodological differences like variance of patient populations, sample size, treatment schedules, disease severity, and assessment tools quantifying disease severity.Citation52

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that the irisin–BDNF axis was assessed with respect to its possible influence on mood disturbances in COPD patients. The ability of exercise to induce BDNF expression in the hippocampus via induction of the FNDC5–irisin pathway has been reported previously in mice.Citation12 Our present results seem to support these findings in humans for the first time.

Limited number of reports deals with the alteration of serum irisin and BDNF levels in COPD patients. Irisin levels were shown to be lower in COPD patients than in controls (31.6 [IQR: 22.7–40.4] ng/mL and 50.7 [IQR: 39.3–65.8] ng/mL, respectively; P<0.001).Citation54 This tendency was present even when patients were divided into subgroups with respect to the level of physical activity: in patients with lower physical activity, serum irisin levels were 23.1 (IQR: 17.3–27.0) ng/mL and 39.6 (IQR: 36.0–43.7) ng/mL in COPD and control patients, respectively.Citation54 Others reported comparable irisin levels of 26.3 (IQR: 22.6–32.4) ng/mL, 53.7 (IQR: 46.7–62.8) ng/mL, and 58.5 (42.8–78.9) ng/mL in smokers with and without COPD and in non-smoking individuals, respectively.Citation55 While the serum BDNF levels measured in our study are higher than those in the study of Stoll et al that included COPD patients,Citation56 they are within the magnitude measured in other studies involving healthy individuals and other patient populations. The reported serum BDNF levels span over five orders of magnitude, ranging from 0.005 to 280 ng/mL,Citation50,Citation52,Citation57,Citation58 depending on the use of different ELISA kits.

A possible limitation of this study comes from its design (cross-sectional study), limiting the possibility to draw cause and effect conclusions. Due diligence was exercised to counterbalance the effect of possible confounders by using multiple linear regression to account for their effect. Characterizing disturbance of mood by the Impacts component score of the SGRQ may also be viewed as a possible shortcoming. Identification of depression based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5 may prove to be challenging as accompanying somatic symptoms could be secondary to either depression or COPD.Citation43 Furthermore, utility of certain diagnostic instruments, for example, hospital anxiety and depression scale, has been questioned with respect to their accuracy in COPD patients.Citation59 Nevertheless, strong correlation between the Impacts score and depression has been described previously,Citation8,Citation60 allowing us to propose that irisin is a possible link between both metabolic disturbances and affective changes. The absence of postbronchodilator whole-body plethysmography may also be viewed as a limitation; however, as previously described,Citation27 this patient population has been included in a COPD management program for a median of 5 (IQR: 3–10) years, hence patients already received bronchodilator therapy and were asked to take their medications as usual in the morning of the examinations. Thus, the current results should be interpreted as on-treatment results. Summarizing, future prospective studies are needed to further underscore the propositions laid out in our current work. Nevertheless, this investigation has several merits like the relatively large clinical patient sample, the use of special tools (whole-body plethysmography and SGRQ, a validated disease-specific questionnaire), furthermore, the stringent data analysis resulting in powerful findings.

In summary, we have found a significant inverse relationship between severity of mood disturbance and serum irisin levels among COPD patients. The fact that this correlation was considerably more influential among patients with BDNF levels below the sample median further supports the possibility that, in COPD, irisin links deterioration of mood to the central effects of BDNF exerted in areas closely associated with reward-related processes involved in the evolution of depression. Furthermore, our findings have a possible practical implication as the efficacy of disease management programs has been shown to depend greatly on the patients’ ability to utilize personal resources like motivation to alter behavior and willingness to set new goals.Citation61 Nonadherence to standard care is very frequent among COPD patients reaching ~70%.Citation3 Considering these aspects, a further consequence of altered irisin–BDNF axis (and downstream processes including mesocortico-limbic dysfunction) may be the impairment of reward-related motivation, preventing change of behavior needed for COPD management and causing lack of efficacy of disease management programs. Future interventional studies investigating the potential beneficial effect of endurance training tailored to the needs of COPD patients with respect to change of irisin–BDNF levels as well as mood and motivation are needed to further support this notion.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contribution of Magdolna Emma Szilasi, Angela Mikaczo, and Andrea Fodor to the present investigation. This study was supported by the Scientific Research Grant of the Hungarian Foundation for Pulmonology (awarded in 2015), the National Research, Development and Innovation Office (GINOP-2.3.2–15-2016–00062 and AGR-PIAC-13–1-2013–0008), and the Hungarian Brain Research Program (KTIA_13_NAP-A-V/2).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- MathersCDLoncarDProjections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030PLoS Med2006311e44217132052

- UchmanowiczIJankowska-PolanskaBMotowidloUUchmanowiczBChabowskiMAssessment of illness acceptance by patients with COPD and the prevalence of depression and anxiety in COPDInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20161196397027274217

- DingBDiBonaventuraMKarlssonNBergströmGHolmgrenUA cross-sectional assessment of the burden of COPD symptoms in the US and Europe using the National Health and Wellness SurveyInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20171252953928223793

- HananiaNAMüllerovaHLocantoreNWEvaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) study investigatorsDeterminants of depression in the ECLIPSE chronic obstructive pulmonary disease cohortAm J Respir Crit Care Med2011183560461120889909

- MikkelsenRLMiddelboeTPisingerCStageKBAnxiety and depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). A reviewNord J Psychiatry2004581657014985157

- NgTNitiMTanWCaoZOngKEngPDepressive symptoms and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: effect on mortality, hospital readmission, symptom burden, functional status, and quality of lifeArch Intern Med20071671606717210879

- OuelletteDRLKRecognition, diagnosis, and treatment of cognitive and psychiatric disorders in patients with COPDInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20171263965028243081

- HynninenMJFactors affecting health status in COPD patients with co-morbid anxiety or depressionInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20072332332818229570

- BoströmPWuJJedrychowskiMPA PGC1-α-dependent myokine that drives brown-fat-like development of white fat and thermogenesisNature2012481738246346822237023

- HandschinCSpiegelmanBMThe role of exercise and PGC1α in inflammation and chronic diseaseNature2008454720346346918650917

- LeckerSHZavinACaoPExpression of the irisin precursor FNDC5 in skeletal muscle correlates with aerobic exercise performance in patients with heart failureCirc Heart Fail20125681281823001918

- WrannCDWhiteJPSalogiannnisJExercise induces hippocampal BDNF through a PGC-1a/FNDC5 pathwayCell Metab201318564965924120943

- SteinerJLMurphyEAMcClellanJLCarmichaelMDDavisJMExercise training increases mitochondrial biogenesis in the brainJ Appl Physiol (1985)201111141066107121817111

- ZsugaJBiroKPappCTajtiGGesztelyiRThe “proactive” model of learning: Integrative framework for model-free and model-based reinforcement learning utilizing the associative learning-based proactive brain conceptBehav Neurosci2016130161826795580

- ZsugaJBiroKTajtiG‘Proactive’ use of cue-context congruence for building reinforcement learning’s reward functionBMC Neurosci20161717027793098

- KristófEDoan-XuanQBaiPBacsoZFésüsLLaser-scanning cytometry can quantify human adipocyte browning and proves effectiveness of irisinSci Rep201551254026212086

- PhillipsCBaktirMASrivatsanMSalehiANeuroprotective effects of physical activity on the brain: a closer look at trophic factor signalingFront Cell Neurosci2014817024999318

- ZsugaJTajtiGPappCJuhaszBGesztelyiRFNDC5/irisin, a molecular target for boosting reward-related learning and motivationMed Hypotheses201690232827063080

- YanQSFengMJYanSEDifferent expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the nucleus accumbens of alcohol-preferring (P) and-nonpreferring (NP) ratsBrain Res20051035221521815722062

- JeanblancJHeDYMcGoughNNThe dopamine D3 receptor is part of a homeostatic pathway regulating ethanol consumptionJ Neurosci20062651457146416452669

- GuillinOGriffonNBezardEBrain-derived neurotrophic factor controls dopamine D3 receptor expression: therapeutic implications in Parkinson’s diseaseEur J Pharmacol20034801–3899514623353

- MaiaTVReinforcement learning, conditioning, and the brain: Successes and challengesCogn Affect Behav Neurosci20099434336419897789

- PulcuETrotterPDThomasEJTemporal discounting in major depressive disorderPsychol Med20144491825183424176142

- HuysQJPizzagalliDABogdanRDayanPMapping anhedonia onto reinforcement learning: a behavioural meta-analysisBiol Mood Anxiety Disord2013311223782813

- NestlerEJCarlezonWAThe mesolimbic dopamine reward circuit in depressionBiol Psychiatry200659121151115916566899

- Von ElmEAltmanDGEggerMPocockSJGøtzschePCVandenbrouckeJPSTROBE InitiativeThe Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studiesInt J Surg20141241495149925046131

- TajtiGGesztelyiRPakKPositive correlation of airway resistance and serum asymmetric dimethylarginine level in COPD patients with systemic markers of low-grade inflammationInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20171287388428352168

- KollégiumTSAz Egészségügyi Minisztérium szakmai irányelve a krónikus obstruktiv légúti betegség (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – COPD) diagnosztikájáról és kezeléséről (1. módosított változat) [Clinical practice guidelines of the Ministry of Health on diagnosis and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (first modified version)]Magyar Közlöny20092136613692 Hungarian

- RabeKFHurdSSAgustíAGGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summaryAm J Respir Crit Care Med2007176653255517507545

- CelliBRMacNeeWATS/ERS Task ForceStandards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paperEur Respir J200423693294615219010

- SwanneyMPRuppelGEnrightPLUsing the lower limit of normal for the FEV1/FVC ratio reduces the misclassification of airway obstructionThorax200863121046105118786983

- NathellLNathellMMalmbergPLarssonKCOPD diagnosis related to different guidelines and spirometry techniquesRespir Res200788918053200

- MeguroMBarleyEASpencerSJonesPWDevelopment and validation of an improved, COPD-specific version of the St. George Respiratory QuestionnaireChest2007132245646317646240

- MillerMRHankinsonJBrusascoVATS/ERS Task ForceStandardisation of spirometryEur Respir J200526231933816055882

- WangerJClausenJLCoatesAStandardisation of the measurement of lung volumesEur Respir J200526351152216135736

- ZsugaJTörökJMagyarMTDimethylarginines at the crossroad of insulin resistance and atherosclerosisMetabolism200756339439917292729

- JonesPWQuirkFBaveystockCThe St George’s respiratory questionnaireRespir Med199185Suppl B2531 discussion 33–371759018

- JonesPWSt. George’s respiratory questionnaire: MCIDCOPD200521757917136966

- FerrerMVillasanteCAlonsoJInterpretation of quality of life scores from the St George’s Respiratory QuestionnaireEur Respir J200219340541311936515

- LambertAAPutchaNDrummondMBCOPD Gene InvestigatorsObesity is associated with increased morbidity in moderate to severe COPDChest20171511687727568229

- HoSCHsuMFKuoHPThe relationship between anthropometric indicators and walking distance in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2015101857186226392760

- TanniSEZamunerATCoelhoLSValeSAGodoyIPaivaSAAre metabolic syndrome and its components associated with 5-year mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients?Metab Syndr Relat Disord2015131525425353094

- CatalfoGCreaLLo CastroTDepression, body mass index, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – a holistic approachInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20161123924926929612

- VogelmeierCFCrinerGJMartinezFJGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease 2017 report: GOLD Executive SummaryAm J Respir Crit Care Med2017195555758228128970

- DiazAAPetersenHMeekPSoodACelliBTesfaigziYDifferences in health-related quality of life between new Mexican hispanic and non-hispanic white smokersChest2016150486987627321735

- WellingJBHartmanJETen HackenNHKloosterKSlebosDJThe minimal important difference for the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire in patients with severe COPDEur Respir J20154661598160426493797

- JonesPWAndersonJACalverleyPMTORCH investigatorsHealth status in the TORCH study of COPD: treatment efficacy and other determinants of changeRespir Res2011127121627828

- DumanRSHeningerGRNestlerEJA molecular and cellular theory of depressionArch Gen Psychiatry19975475976069236543

- JeonSWKimYKMolecular neurobiology and promising new treatment in depressionInt J Mol Sci201617338126999106

- IharaKYoshidaHJonesPBSerum BDNF levels before and after the development of mood disorders: a case-control study in a population cohortTransl Psychiatry20166e78227070410

- BrunoniARLopesMFregniFA systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical studies on major depression and BDNF levels: implications for the role of neuroplasticity in depressionInt J Neuropsychopharmacol20081181169118018752720

- KheirouriSNoorazarSGAlizadehMDana-AlamdariLElevated brain-derived neurotrophic factor correlates negatively with severity and duration of major depressive episodesCogn Behav Neurol2016291243127008247

- GrovesJOIs it time to reassess the BDNF hypothesis of depression?Mol Psychiatry200712121079108817700574

- IjiriNKanazawaHAsaiKWatanabeTHirataKIrisin, a newly discovered myokine, is a novel biomarker associated with physical activity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespirology201520461261725800067

- KureyaYKanazawaHIjiriNDown-regulation of soluble α-Klotho is associated with reduction in serum irisin levels in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseLung2016194334535127140192

- StollPWuertembergerUBratkeKZinglerCVirchowJCLommatzschMStage-dependent association of BDNF and TGF-β 1 with lung function in stable COPDRespir Res20121311623245944

- JacobyASMunkholmKVinbergMPedersenBKKessingLVCytokines, brain-derived neurotrophic factor and C-reactive protein in bipolar I disorder – Results from a prospective studyJ Affect Disord201619716717426994434

- FaillaMDConleyYPWagnerAKBrain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in traumatic brain injury-related mortality: interrelationships between genetics and acute systemic and central nervous system BDNF profilesNeurorehabil Neural Repair2016301839325979196

- ChuangMLLinIFLeeCYClinical assessment tests in evaluating patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a cross-sectional studyMedicine (Baltimore)20169547e547127893695

- JonesPWQuirkFHBaveystockCMLittlejohnsPA self-complete measure of health status for chronic airflow limitationAm Rev Respir Dis19921456132113271595997

- EffingTWLenferinkABuckmanJDevelopment of a self-treatment approach for patients with COPD and comorbidities: an ongoing learning processJ Thorac Dis20146111597160525478200