Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a leading cause of disability and mortality. Caring for patients with COPD, particularly those with advanced disease who experience frequent exacerbations, places a significant burden on health care budgets, and there is a global need to reduce the financial and personal burden of COPD. Evolving scientific evidence on the natural history and clinical course of COPD has fuelled a fundamental shift in our approach to the disease. The emergence of data highlighting the heterogeneity in rate of lung function decline has altered our perception of disease progression in COPD and our understanding of appropriate strategies for the management of stable disease. These data have demonstrated that early, effective, and prolonged bronchodilation has the potential to slow the rate of decline in lung function and to reduce the frequency of exacerbations that contribute to functional decline. The goals of therapy for COPD are no longer confined to controlling symptoms, reducing exacerbations, and maintaining quality of life, and slowing disease progression is now becoming an achievable aim. A challenge for the future will be to capitalize on these observations by improving the identification and diagnosis of patients with COPD early in the course of their disease, so that effective interventions can be introduced before the more advanced, disabling, and costly stages of the disease. Here we critically review emerging data that underpin the advances in our understanding of the clinical course and management of COPD, and evaluate both current and emerging pharmacologic options for effective maintenance treatment.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a leading cause of disability and death worldwide, with population prevalence rates of 5%–13%.Citation1–Citation3 Prevalence rates are related directly to tobacco smoking and indoor air pollution, and are expected to rise as smoking rates continue to increase, notably among women and in developing countries.Citation1,Citation4 By 2030, COPD is expected to represent the third leading cause of death in middle-income countries.Citation4 In addition, COPD accounts for a significant proportion of health care budgets, with the majority of costs being attributed to hospitalizations for exacerbations.Citation5 Thus, there is a global drive to improve COPD diagnosis and management to reduce personal and economic burden.

COPD is characterized by airflow limitation and inflammation, resulting in progressive decline in respiratory function and quality of life (QoL); patients with COPD face a significantly increased risk for premature death.Citation6 The pathologic effects of COPD on the respiratory system are pervasive, affecting the proximal and peripheral airways, lung parenchyma, and pulmonary vasculature.Citation7 The clinical course of COPD may be punctuated by exacerbations that can be life-threatening and associated with worsening outcomes, including increased mortality risk and resource utilization.Citation8,Citation9 Moreover, comorbid conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and depression, as well as associated systemic consequences, including weight loss and muscle dysfunction due to inactivity and deconditioning, add considerably to the overall burden of disease.Citation9,Citation10

COPD is considered to be preventable and treatable,Citation1 yet, despite its high prevalence and significant burden, it remains substantially underdiagnosed and undertreated.Citation11,Citation12 Undiagnosed early-stage patients, especially if they are symptomatic, are more likely to progress to a more severe form of COPD that impacts further on QoL and increases health care costs.Citation12,Citation13

In this article, we draw together the latest understanding of COPD and evaluate current and potential future approaches to long-term treatment.

Methods

A rigorous, directed approach was adopted to identify relevant published literature. PubMed.gov (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez) was searched using the following terms: “COPD” AND “burden, prevalence”, “clinical course”, “lung function decline”, “progression”, “exacerbation, recovery”, “treatment guidelines”, “early treatment”, “maintenance”, “GOLD”, “long-acting bronchodilator”, “long-acting beta-agonist”, “longacting anticholinergic”, “muscarinic antagonist”, and “inhaled corticosteroids”. The search was limited to articles published in English. Given the volume of literature available relating to the etiology, pathophysiology, and management of COPD, key terms were restricted to publication titles as follows: “course”, “decline”, “progression”, “exacerbation”, “guidelines”, “early”, “maintenance”, “GOLD”, and “exacerbation”.

Many national and international respiratory societies have developed guidelines for COPD management.Citation1,Citation14–Citation16 Guideline discussion focuses principally on the internationally recognized Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines,Citation1 upon which many local guidelines are based.

The review of emerging treatment options focuses on pharmacotherapeutic agents recently approved or submitted to regulatory authorities for approval, including indacaterol and roflumilast. The long-acting anticholinergic aclidinium bromide is also discussed. PubMed.gov search terms for these agents were “COPD” AND “[drug name]”.

Major respiratory congress abstract databases (American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society) were also searched from 2007 to 2009. Additional literature was identified by hand-searching reference listings of the publications identified using the approach outlined above.

Evolving concepts of lung function decline

The clinical course of COPD has been viewed as a progressive decline in lung function over time (measured in terms of forced expiratory volume in one second [FEV1]).Citation17 However, recent work suggests that disease progression may not be uniform and that not all patients follow the same clinical course. Furthermore, in addition to smoking, other clinical factors, such as the presence of symptoms, are important in COPD progression.

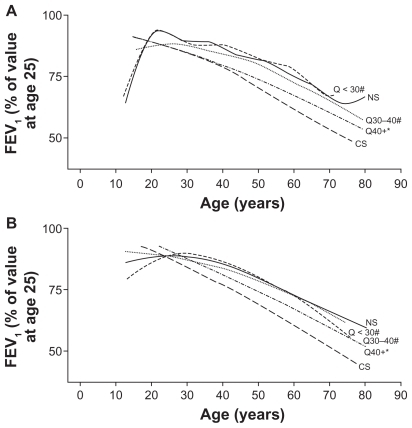

Evidence from the Framingham cohortCitation13 and large-scale interventional trialsCitation18,Citation19 reinforce earlier work demonstrating that annual rates of decline not only differ according to smoking statusCitation17 but, importantly, also appear to be greater during the earlier disease stages. In light of these observations, the Framingham cohort authors have offered an alternative view of disease progression that highlights the heterogeneity of the rate of lung function decline in the context of smoking history ( and accompanying table).Citation13 In contrast with the Fletcher–Peto study,Citation17 the Framingham population includes both men and women, a wide age range (13–71 years), and both working and nonworking participants. It also included close attention to symptoms and a longitudinal follow-up of 23 years.Citation13 Although changes in lung function from adolescence to old age differ in males and females, analysis of the Framingham cohort revealed similar increases in the rate of FEV1 decline in both sexes, and beneficial effects of smoking cessation with age, notably among early quitters.Citation13 Also noteworthy (and in contrast with the observations of Fletcher and Peto),Citation17 symptomatic patients represented a susceptible group for progressive lung function decline, reinforcing current thinking that multidimensional influences impact COPD progression and that early diagnosis and intervention are critical. As such, COPD phenotyping and its impact on disease progression are areas of intense research.Citation20–Citation22 Symptom status also appeared to contribute to the rate of lung function decline among a cohort of 519 patients with GOLD Stage I disease at baseline (according to prebronchodilator spirometry), in that patients with symptomatic disease had a faster decline in FEV1, increased respiratory care utilization, and lower QoL compared with those with asymptomatic disease at baseline.Citation23

Figure 1 Effects of smoking and smoking cessation on decline in lung function among A male and B female adults with chronic obstructive lung disease.Citation13

Notes: *P < 0.05 versus healthy never-smokers; #P < 0.05 versus continuous smokers.

These latter observations highlight the potential for early treatment intervention to relieve dyspnea and thereby maintain or even improve the capacity for physical activity,Citation24 which has been shown to decline during the early disease stages.Citation25 The need for early diagnosis to facilitate early interventions is further underscored by the close relationship between physical activity and clinical functional status.Citation26 Among a cohort of 341 COPD patients hospitalized with a first exacerbation, higher levels of physical activity were associated with significantly higher diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide, expiratory muscle strength, six-minute walking distance, and maximal oxygen uptake.Citation26 In addition, more physically active patients appeared to have reduced systemic inflammation.Citation26 etc Taken together, these data suggest that early diagnosis and interventions to facilitate sustained physical activity could potentially slow disease progression.

Role of exacerbations

Exacerbation frequency appears to exert a negative impact on progressive lung function decline, at least in ex-smokers.Citation27,Citation28 Among a cohort of 109 COPD patients, frequent exacerbators had a significantly faster decline in FEV1 (−40.1 mL/year) and peak expiratory flow (−2.9 L/min/year) compared with infrequent exacerbators (−32.1 mL/year and −0.7 L/min/year, respectively).Citation27 Similarly, in a separate study in 102 patients with COPD, the annual rate of decline in FEV1 was significantly higher among frequent versus infrequent exacerbators (P = 0.017).Citation28

As COPD progresses, exacerbations become more frequent.Citation27,Citation29,Citation30 Donaldson et al reported that patients with severe COPD (GOLD Stage III) had an annual exacerbation frequency of 3.43 compared with 2.68 for patients with moderate COPD (GOLD Stage II, P = 0.029).Citation27

Recent evidence also extends our knowledge of recovery following acute exacerbations. Patients experiencing an acute exacerbation remain at increased risk for subsequent exacerbations during the recovery phase,Citation31 and are markedly inactive during and after hospitalization.Citation32 Indeed, exacerbations tend to occur in clusters, and the two months following an initial exacerbation represent a high-risk period for subsequent exacerbations.Citation33 Some patients also fail to regain their pre-exacerbation symptomatic status.Citation31,Citation34 Such patients appear to experience a persistently heightened inflammatory state.Citation31,Citation35 The rate of lung function decline for these patients has yet to be evaluated, although it has been shown that higher mortality rates are associated with exacerbations.

Current approaches to managing COPD

The internationally recognized GOLD guidelines were developed to increase awareness of COPD and to provide up-to-date information on management approaches.Citation1 Several national guidelines have been issued and are in broad agreement with the GOLD guidelines.Citation14–Citation16 In the UK, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines are currently being updated based on recent evidence of clinical and cost effectiveness of treatment options.

Despite initiatives to improve detection and treatment of COPD, clinical guidelines are poorly implemented in both primaryCitation36,Citation37 and secondary care settings.Citation36,Citation38 Diagnosis is hampered by very limited use of spirometry within primary care because of lack of access and time, cost constraints, inaccurate interpretation of results, and inadequately trained staff.Citation39,Citation40 A recent study suggested only 30% of patients are diagnosed using spirometry according to guideline standards.Citation41 Furthermore, evidence suggests that pharmacologic therapies are frequently prescribed inappropriately and not according to recommendations based on disease severity.Citation18,Citation42

Current pharmacologic maintenance options

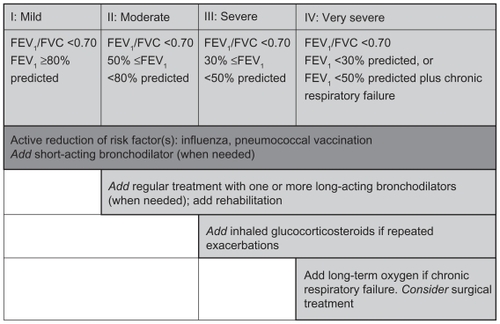

GOLD guidelines advocate a patient-centered, stepwise approach to treatment, depending on disease severity ().Citation1 Intermittent symptoms can be treated with short-acting bronchodilators (SABAs). Several drug classes are approved for maintenance treatment (ie, medication taken regularly to improve symptoms not controlled by SABAs). These include anticholinergics (long-acting antimuscarinic antagonists [LAMAs]), long-acting β2 agonists (LABAs), LABA-inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) combinations, methylxanthines (eg, theophylline), and SABAs and their combinations (). The latter (salbutamol [albuterol]) either alone or in combination with ipratropium is usually reserved for use as rescue medication.

Table 1 Current pharmacologic options for the management of COPDCitation1

Figure 2 The stepwise approach to the management of chronic obstructive lung disease.Citation1

LABAs and LAMAs are currently the preferred pharmacotherapeutic options for maintenance treatment,Citation1 with bronchodilation achieved through different mechanisms (). Currently available long-acting inhaled bronchodilators are the once-daily LAMA, tiotropium, and the twice-daily LABAs, salmeterol and formoterol. The relative benefits of which agent to use first have not been systematically studied; however, tiotropium is widely used and has generally been shown to provide better bronchodilation and clinical outcomes than the twice-daily LABAs.Citation43–Citation46 Based on current evidence, initial treatment with an LAMA appears to be a rational approach, given its ability to reverse the heightened cholinergic tone that predominates in COPD patients.Citation15 LABAs initiate an alternative pathway of bronchodilation.Citation47 When symptoms are not controlled with monotherapy, adding an LABA to an LAMA “dual” long-acting bronchodilator therapy may be more effective than either agent alone, without increased side effects.Citation46,Citation48,Citation49

ICS treatment is not recommended as monotherapy but can provide additional benefits, such as reduced exacerbation frequency, when combined with LABA therapy in patients with moderate and severe COPD and a history of COPD exacerbations.Citation1,Citation19,Citation49 ICS-LABA combinations have been associated with increased risk of pneumonia,Citation19,Citation50,Citation51 with some ICS formulations (fluticasone) putatively more likely to be associated with pneumonia than others (budesonide).Citation48

LAMA plus LABA plus ICS “triple therapy” may have additional clinical benefits and achieve more optimal control in patients with severe COPD, reducing dyspnea and rescue medication use,Citation52 providing greater improvements in lung function,Citation48,Citation52,Citation53 reducing day- and night-time symptoms,Citation48 improving QoL measures,Citation53 and reducing exacerbations.Citation48 Although triple therapy is often used in patients with severe and very severe COPD, there is limited evidence to support the long-term benefits over other combination therapy, and cost constraints may limit its use in clinical practice.

Methylxanthines, such as theophylline, are reserved as third-line options due to their side effect burden, and are only recommended for very severe disease.Citation1 At low doses they may enhance the anti-inflammatory effects of corticosteroidsCitation54 and hence be useful in combination regimens. Long-term oral glucocorticosteroid therapy is not recommended, but may be necessary to treat exacerbations in patients with severe COPD. Patients with viscous sputum may benefit from mucolytic therapy,Citation55 although the overall benefits seem small and routine use is not currently recommended. Other chronic therapies, such as antioxidants, carbocysteine, and N-acetylcysteine, may reduce COPD exacerbations,Citation55–Citation57 but evidence is conflicting.Citation58

For inhaled drugs, delivery systems, correct use, and patient adherence are important considerations when selecting appropriate treatment for individual patients. Inspiratory flow rate is important for correct inhaler use, especially in patients with severe disease; patients should therefore have their technique checked regularly and their flow rate measured if necessary. Adherence to COPD therapies is poor and declines over time,Citation59 which may in part be influenced by the inhaler device. At present, there are limited data to suggest an advantage for one type of inhaler over another for the drugs currently available, although devices that are complicated and require coordination between actuation and inhalation are less likely to be accepted and used effectively.Citation60

Nonpharmacologic treatment options

Although optimal COPD management plans integrate both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions, full consideration of the latter is beyond the scope of this article. However, effective and evidence-based options, including smoking cessation programs, exercise, education, vaccination, pulmonary rehabilitation, and management of comorbidities should be considered and tailored to the individual. Endocrine derangements are common, as is cardiovascular disease.Citation61,Citation62 Pulmonary rehabilitation should be considered for all patients with COPD and may address particular problems, such as exercise deconditioning, relative social isolation, altered mood states (especially depression), muscle wasting, and weight loss, none of which are addressed adequately by current pharmacologic options. Influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations are recommended as an important risk reduction strategy.Citation1

New and emerging options for maintenance treatment

The development of new respiratory medications continues and current research focuses on novel once-daily agents for administration either as monotherapy or in combination with other agents. These include the first once-daily LABA, indacaterol, the selective, once-daily, oral phosphodiesterase (PDE)-4 inhibitor, roflumilast, and the new, most probably twice-daily LAMA, aclidinium.

Indacaterol

Indacaterol was approved for use in the European Union in December 2009 for COPD maintenance treatment and, at the time of writing, is pending approval in the US. European approval was based on data from two pivotal Phase III studies which showed that indacaterol improved lung function (trough FEV1), dyspnea, QoL, and rescue medication use compared with placebo (). Further studies are in progress.

Table 2 Emerging therapies for COPD

The INHANCE (Indacaterol Versus Tiotropium to Help Achieve New COPD Treatment Excellence) study was a 26-week evaluation of indacaterol 150 μg and 300 μg versus placebo and open-label tiotropium in 2059 patients with moderate-to-severe COPD.Citation63 Indacaterol was noted to be suitable for once-daily dosing, and it was thought that it was likely to be “at least as effective as tiotropium for bronchodilation and other clinical outcomes such as dyspnea and health status”. As the authors note, one of the limitations of the study was the open-label comparison, and this needs to be borne in mind when interpreting the study results.Citation63

The INVOLVE (Indacaterol: Value in COPD Pulmonary Disease: Longer-term Validation of Efficacy and Safety) study was a 52-week evaluation of indacaterol 300 μg and 600 μg versus placebo and formoterol 12 μg in 1732 patients with moderate to severe COPD.Citation64 Improvement in lung function was noted when compared with formoterol. “COPD worsening” was the most common adverse event in both studies across active treatment and placebo arms.Citation63,Citation64 No differences in mortality rates compared with placebo were reported in either study.Citation63,Citation64

Roflumilast

Roflumilast is unique among the PDE inhibitors, having selectivity for PDE-4 and no apparent inhibitory effect on PDE-3, which has been associated with cardiotoxicity for other agents in this class.Citation65 Roflumilast is associated with reduced cellular inflammatory activity, and its therapeutic effects include bronchodilation, induction of cytokine and chemokine release from inflammatory cells, and inhibition of microvascular leakage and cellular trafficking. Clinical studies with roflumilast monotherapy demonstrated improved lung function, reduced moderate-to-severe exacerbations, reduced requirement for antiinflammatory/anti-infective medications, and improved QoL measures ().Citation66,Citation67 Similarly, improvements in lung function and exacerbation outcomes were reported when roflumilast was added to tiotropium, or to salmeterol plus fluticasone.Citation68 Notable side effects with roflumilast include headache, weight loss (2.5 kg in all studies at six months and one year), diarrhea, nausea, and stomach ache (ie, gastrointestinal side effects that resulted in a significant early study withdrawal rate).Citation66–Citation68

Approvals for roflumilast are pending; however, it has been recommended for approval in Europe by the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use as maintenance treatment as an “add-on” to bronchodilator therapy in patients with severe COPD (FEV1 <50% predicted) and a history of chronic sputum production and exacerbations.Citation69

Aclidinium

Aclidinium is currently in an earlier stage of clinical development than indacaterol and roflumilast. To date, clinical studies have demonstrated a bronchodilatory effect and an improvement in QoL versus placebo in patients with moderate-to-severe COPD, and an acceptable tolerability profile.Citation70 Preclinical studies suggest a potential for reduced class-related adverse effects with this agent, although confirmation from large-scale clinical trials is awaited.

A number of outstanding questions remain to be answered before the place of indacaterol, roflumilast, and aclidinium in current treatment strategies can be determined. The design of the INHANCE indacaterol study, in which tiotropium was given as open-label therapy, limits the conclusions that can be drawn from these data with regard to the relative efficacy of these agents, and additional data are required from studies that are well controlled. Tolerability issues with roflumilast may limit its use in some patients.Citation66–Citation68

Moving forward: advances in optimal management

COPD is a chronic illness requiring long-term treatment. The clinical aim of maintenance therapy focuses on controlling symptoms and reducing exacerbation frequency. Citation1 Recent data suggest that maintenance bronchodilator therapy may contribute to slowing the rate of lung function decline in symptomatic patients with COPD, raising the potential for disease-course modif ication through ongoing pharmacotherapy.

The first suggestion that long-term bronchodilator therapy might slow FEV1 decline in COPD patients came from a post hoc analysis of 12-month data from two double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled tiotropium trials.Citation71 The mean annual decline in FEV1 was 12 mL versus 58 mL (P = 0.005) among patients receiving tiotropium versus placebo (SABAs only) as maintenance therapy. The potential for maintenance bronchodilator therapy to modify the clinical course of COPD has now been examined in a systematic manner in two largescale, long-term clinical studies, ie, UPLIFT® (Understanding Potential Long-term Impacts on Function with Tiotropium)Citation72 and TORCH (Towards a Revolution in COPD Health).Citation50 Patients in TORCH were randomized to salmeterol and fluticasone propionate (either as monotherapy or in combination), and were permitted use of SABAs and oral corticosteroids to treat exacerbations. Patients in UPLIFT were randomized to tiotropium or placebo and were permitted use of any respiratory medications except inhaled anticholinergics.

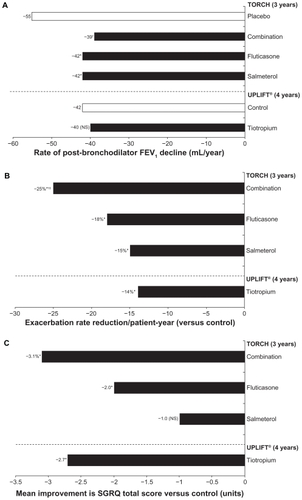

The value of long-term maintenance therapy with bronchodilators in COPD is confirmed by the efficacy, mortality, and safety data from UPLIFT and TORCH ( and , ). Although UPLIFT did not meet its primary endpoint of pre- and postbronchodilator rate of FEV1 decline, the study did demonstrate significantly greater lung function improvements with tiotropium versus placebo at all time points throughout the trial.Citation72 In the TORCH study, lung function was a secondary endpoint, and treatment with salmeterol, fluticasone, or a combination of salmeterol and fluticasone was shown to reduce the rate of lung function decline significantly compared with placebo (, ).Citation73 Absolute changes in lung function in UPLIFT and TORCH were determined using different methodologies. For TORCH, the mean postbronchodilator values were determined following salbutamol 400 μg. It is unclear whether the study drug was administered prior to testing. Study group differences in FEV1 relative to placebo were 42 mL (salmeterol), 47 mL (fluticasone), and 92 mL (combination). Morning predose (trough) values were not measured in TORCH. For UPLIFT, morning trough differences (tiotropium versus placebo) ranged from 87 to 103 mL, and therefore represent the 24-hour effect of tiotropium. In UPLIFT, both treatment groups were sequentially administered salbutamol 400 μg and ipratropium 80 μg in addition to the study drug in order to achieve maximal bronchodilation in both groups. Despite both groups having eight actuations of short-acting bronchodilators, treatment group differences in postbronchodilator FEV1 of 47 to 65 mL were still observed. However, the differences in spirometry protocols render comparisons between the two trials invalid.

Table 3 UPLIFT and TORCH efficacy summary50,72,73

Table 4 UPLIFT and TORCH safety and mortality summaryCitation50,Citation72,Citation73

Figure 3 Impact of maintenance bronchodilation on A) the rate of decline in lung function, B) exacerbations, and C) quality of life.Citation50,Citation72,Citation73

Notes: A) *P < 0.003 versus placebo; †P f< 0.001 versus; B) *P < 0.001 versus control; †P < 0.02 versus salmeterol; ‡P < 0.02 versus fluticasone; C) *P < 0.001 versus control.

The primary endpoint of achieving a significant decrease in mortality among patients treated with combination therapy versus placebo was not reached in TORCH.Citation15 However, both TORCH and UPLIFT demonstrated the potential to reduce exacerbation frequency significantly with bronchodilator maintenance therapy (, ). This finding is of considerable importance for all COPD patients with more advanced disease, given recent data indicating heterogeneity in terms of symptomatic recovery from acute COPD exacerbations and the potential of exacerbations to contribute to disease progression.Citation31,Citation34 In both the UPLIFT and TORCH studies, statistically significant improvements in QoL (St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire total scores) were observed with all active treatments versus placebo (except salmeterol monotherapy in TORCH), although these improvements were not clinically significant ().Citation50,Citation72 In UPLIFT, a greater proportion of patients in the tiotropium group than in the placebo group achieved a clinically significant improvement of ≥4 units on the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire total score.Citation72

UPLIFT and TORCH have also contributed important information about COPD patients in terms of common comorbidities, smoking status, and concomitant medications, in addition to patient characteristics that might influence the rate of FEV1 decline. For example, a more rapid FEV1 decline was reported in patients with a lower body mass index and in younger (<55 years) compared with older patients, the latter observation being consistent with the recent Framingham Cohort Study reports.Citation13 Bronchodilator responsiveness was found to be far more common in COPD than previously recognized and did not impact either the short- or long-term responses to bronchodilator treatment.Citation72,Citation74

Treating patients earlier in the disease course

The potential for disease-course modification with long-term maintenance therapy is perhaps the single most encouraging outcome from the UPLIFT and TORCH studies in terms of improving prognosis. To date, only smoking cessation has been shown to change the clinical course of COPD,Citation75 although long-term oxygen therapy leads to a survival advantage,Citation76 and pulmonary rehabilitation has been shown to improve dyspnea and exercise capacity and to reduce exacerbation rate and severity.Citation16

Data from both studies indicate the potential to slow the rate of lung function decline and thus change the clinical course of disease for patients diagnosed and treated early. Post hoc and subgroup analyses have shown that initiating maintenance treatment at earlier disease stages can have a greater impact than introducing treatment at later stages with respect to improvements in QoL, reduction in risk/frequency of exacerbations, improving lung function, and potentially reducing mortality ().Citation18,Citation19,Citation77,Citation78 Both studies demonstrated a slower rate of FEV1 decline compared with placebo for patients with GOLD Stage II disease. In UPLIFT, significant benefits in disease progression and QoL were observed in patients who were maintenance-treatment-naïve at study initiation,Citation78 and those aged ≤50 years.Citation77 The effects of maintenance pharmacotherapy in early-stage disease need to be rigorously investigated in well designed, prospective studies.

Table 5 UPLIFT and TORCH subgroup efficacy results for earlier diseaseCitation18,Citation19,Citation77,Citation78

Implications for future COPD management

In order for the full benefit of the findings from the UPLIFT and TORCH studies to be incorporated into clinical practice, it is necessary to identify early-stage patients. This will require heightened COPD awareness among both patients and physicians. A major barrier to early detection is that patients often do not recognize the early symptoms, or consider them a consequence of aging or smoking.

Spirometry that is performed and interpreted properly is a critical step in the accurate diagnosis of COPD, as is the collection/assessment of patient-reported outcomes and health status, including smoking history, occupation (past and present), daily symptoms (eg, breathlessness, cough, sputum production), activity limitation, and other disease manifestations. Improved identification of patients at risk for developing COPD, based on recognized risk factors and symptoms, is required to enable early diagnosis and to initiate prompt maintenance treatment. Diagnostic tools and questionnaires (eg, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire, Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire) can facilitate clinical assessment; however, their length precludes practical application in everyday practice. Two shortened and simplified COPD screening tools may be more suited to clinical settings and for the general public, ie, the COPD Assessment TestCitation79 and the self-administered COPD Population ScreenerTM.Citation80 These tools may help to identify patients likely to have COPD, but further evaluation and validation is required to confirm their usefulness in clinical practice.

Programs to educate both physicians and patients are also necessary to increase vigilance for early signs and symptoms, including increased recognition that COPD is not restricted to the elderly but can also affect younger people in their 30s and 40s,Citation81 and removal of the nihilistic attitude that COPD is a self-inflicted disease. Improved adherence to treatment guidelines, including correct implementation of spirometry, is also required.

Conclusion

The emergence of scientific evidence from multiple sources, including large clinical trials, has expanded our knowledge of COPD and fuelled a shift in our understanding of lung function decline and disease progression. Coupled with the emergence of a range of new drug treatments with differing mechanisms of action targeting different physiologic aspects of the disease, the first decade of this new century has become an exciting period in COPD management. The current challenge is to apply our understanding of disease processes to the design of optimal treatment algorithms for maintenance therapy, encompassing both established and emerging drug treatments. Landmark clinical trial data reinforce when foundation maintenance therapy should be introduced for symptomatic patients with COPD and its long-term health benefits. Finally, emerging evidence supports the early introduction of pharmacotherapies that relieve breathlessness, with the aim of slowing lung function decline and reducing the risk of acute exacerbations. However, further studies are required before evidence-based guidelines are able to assess adequately the potential of treatment for early-stage disease.

Disclosure

Writing and editorial assistance was provided by PAREXEL MMS writers Claire Scarborough and Natalie Barker. Those services were contracted by Boehringer Ingelheim GmbH and Pfizer Inc. The authors received no financial compensation related to the development of the manuscript.

References

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung DiseaseGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease Updated 2009. Available from: www.goldcopd.comAccessed 2010 May 12

- BuistASVollmerWMMcBurnieMAWorldwide burden of COPD in high- and low-income countries. Part I. The burden of obstructive lung disease (BOLD) initiativeInt J Tuberc Lung Dis20081270370818544191

- ManninoDMBuistASGlobal burden of COPD: Risk factors, prevalence, and future trendsLancet200737076577317765526

- MathersCDLoncarDProjections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030PLoS Med20063e44217132052

- SullivanSDRamseySDLeeTAThe economic burden of COPDChest2000117S59

- ShavelleRMPaculdoDRKushSJManninoDMStraussDJLife expectancy and years of life lost in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Findings from the NHANES III Follow-up StudyInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2009413714819436692

- HoggJCPathophysiology of airflow limitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseLancet200436470972115325838

- CooperCBDransfieldMPrimary care of the patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – Part 4: Understanding the clinical manifestations of a progressive diseaseAm J Med20081217 SupplS334518558106

- WoutersEFEconomic analysis of the Confronting COPD survey: An overview of resultsRespir Med200397Suppl CS31412647938

- ChatilaWMThomashowBMMinaiOACrinerGJMakeBJComorbidities in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseProc Am Thorac Soc2008554955518453370

- LindbergAJonssonACRonmarkELundgrenRLarssonLGLundbäckBPrevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease according to BTS, ERS, GOLD and ATS criteria in relation to doctor’s diagnosis, symptoms, age, gender, and smoking habitsRespiration20057247147916210885

- British Lung FoundationInvisible livesChronic obstructive lung disease (COPD) – finding the missing millions Available from: http://www.lunguk.orgAccessed 2010 May 12

- KohansalRMartinez-CamblorPAgustiABuistASManninoDMSorianoJBThe natural history of chronic airflow obstruction revisited: An analysis of the Framingham offspring cohortAm J Respir Crit Care Med200918031019342411

- CelliBRMacNeeWATS/ERS Task ForceStandards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: A summary of the ATS/ERS position paperEur Respir J20042393294615219010

- O’DonnellDEAaronSBourbeauJCanadian Thoracic Society recommendations for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – 2007 updateCan Respir J200714Suppl BB532

- HalpinDNICE guidance for COPDThorax20045918118214985544

- FletcherCPetoRThe natural history of chronic airflow obstructionBr Med J1977116451648871704

- DecramerMCelliBKestenSLystigTMehraSTashkinDPUPLIFT investigatorsEffect of tiotropium on outcomes in patients with moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (UPLIFT): A prespecified subgroup analysis of a randomised controlled trialLancet20093741171117819716598

- JenkinsCRJonesPWCalverleyPMEfficacy of salmeterol/fluticasone propionate by GOLD stage of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Analysis from the randomised, placebo-controlled TORCH studyRespir Res2009105919566934

- ManninoDMWattGHoleDThe natural history of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur Respir J20062762764316507865

- TashkinDPFrequent exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – a distinct phenotypeNew Engl J Med20103631183118420843256

- HurstJRVestboJAnzuetoASusceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseNew Engl J Med20103631128113820843247

- BridevauxPOGerbaseMWProbst-HenschNMSchindlerCGaspozJMRochatTLong-term decline in lung function, utilisation of care and quality of life in modified GOLD stage 1 COPDThorax20086376877418505800

- OfirDLavenezianaPWebbKALamYMO’DonnellDEMechanisms of dyspnea during cycle exercise in symptomatic patients with GOLD stage I chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med200817762262918006885

- TroostersTSciurbaFBattagliaSPhysical inactivity in patients with COPD, a controlled multi-center pilot-studyRespir Med20101041005101120167463

- Garcia-AymerichJSerraIGómezFPPhysical activity and clinical and functional status in COPDChest2009136627019255291

- DonaldsonGCSeemungalTARBhowmikAWedzichaJARelationship between exacerbation frequency and lung function decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax20025784785212324669

- MakrisDMoschandreasJDamianakiAExacerbations and lung function decline in COPD: New insights in current and ex-smokersRespir Med20071011305131217112715

- PaggiaroPLDahleRBakranIMulticentre randomised placebocontrolled trial of inhaled fluticasone propionate in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. International COPD Study GroupLancet19983517737809519948

- GompertzSBayleyDLHillSLStockleyRARelationship between airway inflammation and the frequency of exacerbations in patients with smoking related COPDThorax200156364111120902

- PereraWRHurstJRWilkinsonTMInflammatory changes, recovery and recurrence at COPD exacerbationEur Respir J20072952753417107990

- PittaFTroostersTProbstVSSpruitMADecramerMGosselinkRPhysical activity and hospitalization for exacerbation of COPDChest200612953654416537849

- HurstJRDonaldsonGCQuintJKGoldringJJBaghai-RavaryRWedzichaJATemporal clustering of exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med200917936937419074596

- TsaiCLRoweBHCamargoCAJrFactors associated with short-term recovery of health status among emergency department patients with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseQual Life Res20091819119919123070

- GroenewegenKHDentenerMAWoutersEFLongitudinal follow-up of systemic inflammation after acute exacerbations of COPDRespir Med20071012409241517644367

- GlaabTBanikNRutschmannOTWenckerMNational survey of guideline-compliant COPD management among pneumologists and primary care physiciansCOPD2006314114817240616

- RutschmannOTJanssensJPVermeulenBSarasinFPKnowledge of guidelines for the management of COPD: A survey of primary care physiciansRespir Med20049893293715481268

- TaMGeorgeJManagement of COPD in Australia after the publication of national guidelinesIntern Med J

- DeromEvan WeelCLiistroGPrimary care spirometryEur Respir J20083119720318166597

- LusuardiMDe BenedettoFPaggiaroPA randomized controlled trial on off ice spirometry in asthma and COPD in standard general practice: Data from spirometry in asthma and COPD: A comparative evaluation Italian studyChest200612984485216608929

- ArneMLisspersKStällbergBBomanGHow often is diagnosis of COPD confirmed with spirometryRespir Med201010455055619931443

- JonesRCDickson-SpillmannMMatherMJMarksDShackellBSAccuracy of diagnostic registers and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: The Devon primary care auditRespir Res200896218710575

- DonohueJFvan NoordJABatemanEDA 6-month, placebocontrolled study comparing lung function and health status changes in COPD patients treated with tiotropium or salmeterolChest2002122475512114338

- BrusascoVHodderRMiravitllesMKorduckiLTowseLKestenSHealth outcomes following treatment for six months with once daily tiotropium compared with twice daily salmeterol in patients with COPDThorax2006619116396956

- VogelmeierCKardosPHarariSGansSJStengleinSThirlwellJFormoterol mono- and combination therapy with tiotropium in patients with COPD: A 6-month studyRespir Med20081021511152018804362

- van NoordJAAumannJLJanssensEComparison of tiotropium once daily, formoterol twice daily and both combined once daily in patients with COPDEur Respir J20052621422216055868

- VinckenWBronchodilator treatment of stable COPD: Long-acting anticholinergicsEur Respir Rev2005142331

- WelteTMiravitllesMHernandezPEfficacy and tolerability of budesonide/formoterol added to tiotropium in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med200918074175019644045

- CazzolaMDahlRInhaled combination therapy with longacting beta 2-agonists and corticosteroids in stable COPDChest200412622023715249466

- CalverleyPMAndersonJACelliBTORCH investigatorsSalmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med200735677578917314337

- WedzichaJACalverleyPMSeemungalTAHaganGAnsariZStockleyRAINSPIRE InvestigatorsThe prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations by salmeterol/fluticasone propionate or tiotropium bromideAm J Respir Crit Care Med2008177192617916806

- SinghDBrooksJHaganGCahnAO’ConnorBJSuperiority of “triple” therapy with salmeterol/fluticasone propionate and tiotropium bromide versus individual components in moderate to severe COPDThorax20086359259818245142

- PerngDWWuCCSuKCLeeYCPerngRPTaoCWAdditive benefits of tiotropium in COPD patients treated with long-acting beta agonists and corticosteroidsRespirology20061159860216916333

- CosioBGIglesiasARiosALow-dose theophylline enhances the anti-inflammatory effects of steroids during exacerbations of COPDThorax20096442442919158122

- PoolePJBlackPNMucolytic agents for chronic bronchitis or chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20033CD001287

- SteyCSteurerJBachmannSMediciTCTramèrMRThe effect of oral N-acetylcysteine in chronic bronchitis: A quantitative systematic reviewEur Respir J20001625326210968500

- ZhengJPKangJHuangSGEffect of carbocisteine on acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (PEACE Study): A randomised placebo-controlled studyLancet20083712013201818555912

- DecramerMRutten-van MölkenMDekhuijzenPNEffects of N-acetylcysteine on outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Bronchitis Randomized on NAC Cost-Utility Study, BRONCUS): A randomised placebo-controlled trialLancet20053651552156015866309

- VestboJAndersonJACalverleyPMAdherence to inhaled therapy, mortality and hospital admission in COPDThorax20096493994319703830

- BatemanEDImproving inhaler use in COPD and the role of patient preferenceEur Respir Rev2005148588

- LaghiFAdiguzelNTobinMJEndocrinological derangements in COPDEur Respir J20093497599619797671

- DecramerMRennardSTroostersTCOPD as a lung disease with systemic consequences – clinical impact, mechanisms, and potential for early interventionCOPD2008523525618671149

- DonohueJFFogartyCLötvallJINHANCE study investigatorsOnce-daily bronchodilators for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Indacaterol versus tiotropiumAm J Respir Crit Care Med201018215516220463178

- DahlRChungKFBuhlRINVOLVE (INdacaterol: Value in COPD: Longer Term Validation of Efficacy and Safety) Study InvestigatorsEfficacy of a new once-daily long-acting inhaled beta2- agonist indacaterol versus twice-daily formoterol in COPDThorax20106547347920522841

- SotoFJHananiaNASelective phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors in chronic obstructive lung diseaseCurr Opin Pulm Med20051112913415699784

- CalverleyPMRabeKFGoehringUMKristiansenSFabbriLMMartinezFJM2–124 and M2–125 study groups. Roflumilast in symptomatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Two randomised clinical trialsLancet200937468569419716960

- RabeKFBatemanEDO’DonnellDWitteSBredenbrökerDBethkeTDRoflumilast – an oral anti-inflammatory treatment for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A randomised controlled trialLancet200536656357116099292

- FabbriLMCalverleyPMIzquierdo-AlonsoJLBroseMMartinezFJRabeKFM2-127 and M2-128 study groups. Roflumilast in moderate-to- severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease treated with longacting bronchodilators: Two randomised clinical trialsLancet200937469570319716961

- European Medicines Agency and Committee for Medicinal Products for Human UseSummary of opinion (initial authorisation)Daxas. Roflumilast Available from: http://www.ema.europa.euAccessed 2010 May 12

- ChanezPAclidinium bromide provides long-acting bronchodilation in patients with COPDPulm Pharmacol Ther201023152119683590

- AnzuetoATashkinDMenjogeSKestenSOne-year analysis of longitudinal changes in spirometry in patients with COPD receiving tiotropiumPulm Pharmacol Ther200518758115649848

- TashkinDPCelliBSennSUPLIFT® Study InvestigatorsA 4-year trial of tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med20083591543155418836213

- CelliBRThomasNEAndersonJAEffect of pharmacotherapy on rate of decline of lung function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Results from the TORCH studyAm J Respir Crit Care Med200817833233818511702

- HananiaNKestenSCelliBAcute bronchodilator response does not predict health outcomes in patients with COPD treated with tiotropiumEur Respir J200934Suppl 53S777

- AnthonisenNRConnettJEKileyJPEffects of smoking intervention and the use of an inhaled anticholinergic bronchodilator on the rate of decline of FEV1. The Lung Health StudyJAMA1994272149715057966841

- Long term domiciliary oxygen therapy in chronic hypoxic cor pulmonale complicating chronic bronchitis and emphysema Report of the Medical Research Council Working PartyLancet198116816866110912

- MoriceAHCelliBKestenSLystigTTashkinDDecramerMCOPD in young patients: A pre-specified analysis of the four-year trial of tiotropium (UPLIFT)Respir Med20101041659166720724131

- TroostersTCelliBLystigTTiotropium as a first maintenance drug in COPD: Secondary analysis of the UPLIFT® trialEur Respir J201036657320185426

- JonesPHardingGWiklundIBerryPLeidyNImproving the process and outcome of care in COPD: Development of a standardised assessment toolPrim Care Respir J20091820821519690787

- MartinezFJRaczekAESeiferFDDevelopment and initial validation of a self-scored COPD Population Screener Questionnaire (COPD-PS)COPD20085859518415807

- de MarcoRAccordiniSCerveriICorsicoASunyerJNeukirchFAn international survey of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in young adults according to GOLD stagesThorax20045912012514760151