Abstract

Background

Recent guidelines for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) state that COPD is both preventable and treatable. To gain a more positive outlook on the disease it is interesting to investigate factors associated with good, self-rated health and quality of life in subjects with self-reported COPD in the population.

Methods

In a cross-sectional study design, postal survey questionnaires were sent to a stratified, random population in Sweden in 2004 and 2008. The prevalence of subjects (40–84 years) who reported having COPD was 2.1% in 2004 and 2.7% in 2008. Data were analyzed for 1475 subjects. Regression models were used to analyze the associations between health measures (general health status, the General Health Questionnaire, the EuroQol five-dimension questionnaire) and influencing factors.

Results

The most important factor associated with good, self-rated health and quality of life was level of physical activity. Odds ratios for general health varied from 2.4 to 7.7 depending on degree of physical activity, where subjects with the highest physical activity level reported the best health and also highest quality of life. Social support and absence of economic problems almost doubled the odds ratios for better health and quality of life.

Conclusions

In this population-based public health survey, better self-rated health status and quality of life in subjects with self-reported COPD was associated with higher levels of physical activity, social support, and absence of economic problems. The findings indicated that of possible factors that could be influenced, promoting physical activity and strengthening social support are important in maintaining or improving the health and quality of life in subjects with COPD. Severity of the disease as a possible confounding effect should be investigated in future population studies.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a major public health problem in persons over 40.Citation1 Further increases in the prevalence and mortality of COPD can be expected over the coming decades.Citation2 People in general had little knowledge about the disease,Citation3 but during the last decade COPD has become a widely recognized disease entity. Those with self-reported COPD in the adult population can now be identified and questioned about their health status and quality of life.

The World Health Organization (WHO) (1948) defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”. In later years, a salutogenic approach focusing on factors supporting health and well-being has successively been introducedCitation4 and was supported by the WHO Ottawa Charter of 1986,Citation5 which advocated a reorientation of health services towards the promotion of health. Knowledge about predictors of good health can support health-promoting activities among individuals with chronic disorders.Citation6 Thus, a health-promoting society for healthy people as well as for those with chronic diseases could be created, both at societal and individual levels.Citation7

We have previously shown that subjects with chronic disease have a low general health status and a low level of physical activity compared with healthy subjects.Citation8 Subjects with COPD are particularly restricted in their activities. Patients with COPD can be impaired in all domains of health-related quality of lifeCitation9 and depression in patients with COPD seems associated with poor exercise performance and lower health status.Citation10 Studies often focus on risk factors and negative aspects, with a focus on ill-health,Citation11 while determinants of good health have been studied less extensively.Citation12

Recent guidelines for COPD state that COPD is both preventable and treatable.Citation2 In addition, the importance of increasing awareness of COPD, to promote a healthy lifestyle and encourage physical activity in all patients with COPD has been emphasized.Citation13 Therefore, investigating factors associated with good health in subjects with COPD is of great interest.

The aim of this study was to investigate factors associated with good, self-rated health and quality of life in subjects with self-reported COPD.

Study population and methods

Study population

Two population surveys including men and women were performed in 2004 and 2008. Data were obtained in August–November 2004 and March–April 2008 using a postal survey questionnaire in Swedish. The area investigated covered 55 municipalities in five counties in central Sweden with approximately one million inhabitants. The sampling was random after stratification for gender, age group, county, and municipality. Data collection was completed after two postal reminders.

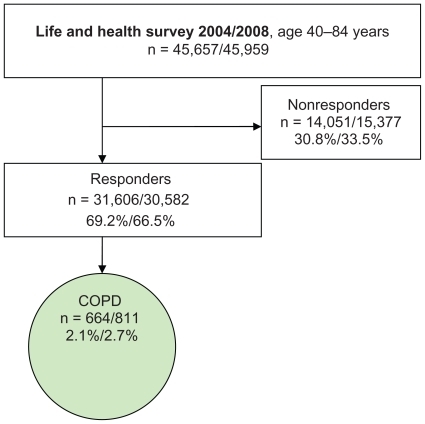

In the studied subsample of the present study (age group 40–84 years) the questionnaire was sent to 45,657 persons (2004) and 45,959 persons (2008) (). A total of 31,606 (2004) and 30,582 (2008) persons answered the questionnaire with a response rate of 69.2% (2004) and 66.5% (2008). All subjects who answered “Yes, COPD” to the question “Have you or have you had any of the following longstanding diseases or problems during the past 12 months”, were included (). The prevalence of subjects who stated having COPD in the sample was 2.1% in 2004 and 2.7% in 2008. Due to the low reported prevalence of COPD, the results from the two surveys were combined to obtain a larger population for analysis. The probability of the same person answering both surveys was 2.4% and this possible overlap was assessed as not influencing results.

Table 1 Characteristics of the subjects (n = 1475)

Methods

The factors associated with health status and quality of life in those with self-reported COPD were analyzed.

Outcome variables – health status and quality of life

General health status was assessed by the answer to the question “How do you rate your general health status?” with the alternatives; “Very good/Good/Neither good nor poor/Poor/Very poor”.Citation14

The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) is a self-reported questionnaire designed to identify psychological disorders, mainly within the anxiety/depression spectrum. In the present study the 12-item version (GHQ12) was used.Citation15 Scores were calculated from dichotomizing the 12 items (0 = equal or better than usual, 1 = worse than usual), and psychological distress was defined as present when the total score was 3 or higher.

The EuroQol five-dimension questionnaire (EQ-5D), consists of the five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression, each of which offered three possible responses: “No problems/Some or moderate problems/Extreme problems”. The index of EQ-5D was computed according to Burström et al,Citation16 (1 = full health, 0 = death).

The factors potentially associated with outcome variables were: age and sex, which are basic factors in all models. In regression analyses, age and body mass index (BMI; body weight divided by the square of height) are standardized.

Economic problems were described by answers to the question: “Have you had difficulties in managing expenditures for food, rent, bills, etc. during the past 12 months?” with the alternatives: “No” or “Yes, 1 month/Yes, 2 months/Yes, 3–5 months/Yes, 6–12 months”; all Yes-alternatives were classified as “Yes”.

Alcohol use was categorized by five categories: “Never/Once a month or less/2–4 times a month/2–3 times a week/4 times a week or more”. Educational level was combined into the categories: “Compulsory school/Grammar school/University/Other”.

Social support was assessed according to the question: “Do you have any persons in your vicinity who can provide you with personal support in case of personal problems or life crises?” with the alternatives: “Yes, undoubtedly/Yes, probably/Presumably not/No”; where “No” and “Presumably not” were classified as “No”.

Smoking status contained four alternatives: “Never smoked/Stopped smoking (ex-smoker)/Intermittent smoker/Daily smoker”. The latter two alternatives were combined to “Current smoker”.

Physical activity in leisure time was estimated on a four-category scale indicating (A) sedentary (mostly sitting or low activity <2 hours a week); (B) moderate exercise (low activity >2 hours a week); (C) moderate regular exercise (high activity >30 minutes, 1–2 times a week); (D) regular exercise and training (high activity >30 minutes ≥3 times a week).

Health care utilization was indicated by a “Yes” response to the question: “Have you, due to symptoms or disease, visited a doctor in a hospital emergency department during the past three months?” or “Have you, due to symptoms or disease, been admitted to a hospital during the past three months?”

Comorbidity factors

Comorbidities often associated with COPD were captured by “Yes” answers to the question about presence of longstanding diseases or problems in the last 12 months. These diseases or problems were cardiovascular disease, hypertension, asthma, depression, and chronic fatigue syndrome.

Statistical methods

For descriptive analysis we used means, standard deviations, and proportions along with t-tests and chi-square tests for associations. Regression models were used to analyze the association between health measures (general health status, GHQ12 index, EQ-5D) and a predefined set of explanatory variables. These are added in two blocks for each health measure: block 1 – sex, age, and additional factors (BMI, economic problems, alcohol use, educational level, social support, smoking status, and physical activity), and block 2 – comorbidity factors (cardiovascular disease, hypertension, asthma, depression, and chronic fatigue syndrome). Because there are correlations between comorbidities they are added one at a time in separate analyses. The purpose of block 2 is to see whether comorbidity has any influence on the associations between explanatory variables and outcome.

For GHQ12 we used logistic regression, with odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). For general health we tested the proportional odds assumption in ordinal logistic regression and, when necessary, used partial proportional odds or multinomial regression models instead. All regression analyses for general health were made using the Stata command gologit2,Citation17 with automatic testing of the proportional odds assumption both globally and for each variable respectively. For EQ-5D we tested the normal assumption of linear regression. Because the data showed significant deviations, we used median regression instead.Citation18

Nonlinear effects of age and BMI were tested using multivariate fractional polynomials (FP).Citation19 The estimation routine for fractional polynomials starts with a linear regression model and is expanded when indicated by data, resulting in a parsimonious model still complex enough to describe associations present in data. Associations were measured using odds ratios with 95% CI.

All analyses were performed using Stata/IC (v 10; Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX).

Ethics

According to the Swedish laws of medical research ethics, population studies with de-identified personal data do not require ethical approval. The reasoning behind this is that the respondent gave consent when returning the questionnaire.

Results

The mean age was 69.1 years (females 67.0 and males 69.9 years), and more men than women had self-reported COPD (). One-third were current smokers, and 28% of all subjects were daily smokers. A total of 83% reported physical activity on the two lowest levels, and a sedentary lifestyle was stated by 39%. There was no difference in reported physical activity between the years 2004 and 2008. Compulsory school was the highest educational level in 57% and more than 84% were retired, on sick leave, or had a sickness pension. Comorbidity was present with cardiovascular disease in 34%, hypertension, or asthma in more than 40%, depression in 26%, and chronic fatigue syndrome in 22%. More than 23% had visited an emergency department during the past 3 months, compared with 8%–9% in age-matched subjects without COPD, and 14% had been admitted to hospital.

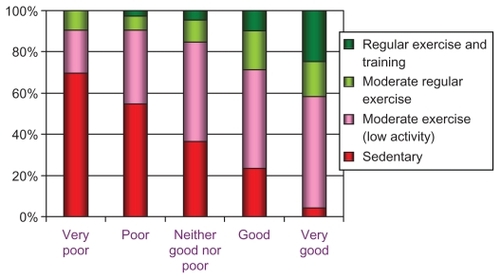

General health status was reported as “very good/good” in 24% () and psychological well-being was not impaired in 77%. Quality of life (EQ-5D) was graded as “no problems” by half the subjects regarding mobility and anxiety/depression, while 14% had “no problems” with pain/discomfort, and more than 60% had “no problems” with usual activities. A slightly better status on the health and quality of life measures could be seen in 2008 compared with 2004 (). Unadjusted relations between self-reported health status and level of physical activity are described in .

Table 2 General health and quality of life (n = 1 475)

Figure 2 Relationship between self-rated general health (x-axis) and physical activity in leisure time.

The regression analyses of self-reported general health diagnostic tests showed deviations from the proportional odds assumption for some variables (age, economic problems, alcohol use, and smoking status) and, as a consequence, partial proportional odds models were used. The heterogeneous associations for these four variables are described in as four odds ratios (odds comparing “Very bad” vs “Bad”, “Bad” vs “Neither good nor bad”, “Neither good nor bad” vs “Good”, and “Good” vs “Very good”) for each variable. These odds ratios were interpreted as ordinary odds ratios where, for example, the reference outcome was “Neither good nor bad” the other was “Good”. Tests of nonlinear effects for age and BMI only showed significant nonlinear associations for age in the analysis of GHQ12.

Table 3 Associations between background factors and measures of general health and quality of life

Age showed a linear association with self-reported general health, but only when comparing outcome “Good” to “Neither good nor bad” or when comparing “Very good” to “Good”. Age showed a U-shaped association with GHQ12 with the lowest odds for having psychological distress at 68 years.

Economic problems were associated with all three health measures, where reporting no economic problems was associated with higher odds for better self-reported general health, lower odds for psychological distress, and increased median of EQ-5D. For self-reported general health the association was significant only when comparing “Good” to “Neither good nor bad” health states.

Alcohol use was associated with self-reported general health (only when comparing “Bad” to “Very bad”) and weakly associated to EQ-5D. For both measures the reporting of no alcohol use was associated with lower levels of health.

Social support was associated with better status for all three health measures.

Smoking status was significantly associated with higher odds for better self-reported general health and lower odds for psychological distress for those reporting “Never smoked”.

Physical activity was associated at all levels with all three health measures. For self-reported general health, the odds of having better health were multiplied by a factor 2.4–7.7 depending on activity level. The odds of being psychologically distressed were reduced by approximately 50%. The median EQ-5D index increased with 0.04–0.09 depending on activity level.

There were no significant associations between the three health measures and sex, BMI, or educational level.

EQ-5D was associated with cardiovascular disease (effect on median [95% CI]): (−0.05, [−0.07, −0.03]), depression (−0.10 [−0.13, −0.07]), and chronic fatigue syndrome (−0.07, [−0.09, −0.05]), but not with hypertension or asthma.

Psychological distress was associated with depression (OR [95% CI]): (6.60 [3.92, 8.01]) and chronic fatigue syndrome (3.77 [2.61, 5.44]), but not with cardiovascular disease, hypertension, or asthma.

Self-reported general health was associated with cardiovascular disease when comparing “Neither good nor bad” to “Bad” (OR [95% CI]): (0.39 [0.29, 0.52]) and when comparing “Neither good nor bad” to “Good” (0.57 [0.41, 0.80]) and with asthma (0.73 [0.57, 0.95]) regardless of health state). For depression there were significant associations between self-reported general health and depression (OR range 0.30–0.73) and chronic fatigue syndrome (OR range 0.26–0.66), except when comparing “Very good” and “Good”. There were no associations between self-reported general health and hypertension.

Adjusting for comorbid conditions (cardiovascular disease, hypertension, asthma, depression, and chronic fatigue syndrome), however, did not alter the associations presented in in any significant way.

Discussion

This study has shown that subjects with COPD when combined with good health and good quality of life were physically active. The higher the physical activity levels the better their health and quality of life. We also showed that even a low level of physical activity was better than a sedentary lifestyle.

Our results were in accordance with Garcia-Aymerich et al who, in an epidemiological study, assessed daily life activities in subjects with COPD and found associations between higher levels of regular physical activity and better functional status.Citation20 They also showed that physically active subjects with COPD had a lower risk of COPD admissions and mortality. They proposed that physical activity should be widely recommended for patients with COPD in COPD guidelines.Citation21 Our results were also in accordance with those from an asthma population in Canada,Citation22 where those with good self-reported health are more physically active. Pitta et al, also showed that encouragement to be more active in daily life is an important part of the management of patients with COPD.Citation23

Clinical studies have also shown that patients with COPD spend less time walking and standing compared with age- and sex-matched healthy subjects and activity is on a lower intensity levelCitation23 that is not sufficient to promote and maintain health.Citation24

Multidisciplinary pulmonary rehabilitation is a basis for treatment of COPD, with evidence for improvement in exercise endurance, dyspnea, functional capacity, and quality of life.Citation23 Exercise training is a cornerstone of the concept of rehabilitation.Citation2 As the majority of patients with COPD are treated in primary care, it is important to make it possible for them to enter programs including physical training in primary care settings.Citation25 However, better functional status is associated with daily life activities rather than planned exercise activities,Citation21 which is encouraging because regular spontaneous physical activity is easier for most subjects with COPD. In a recent study, Watz et alCitation26 investigated physical activity in patients with COPD and found that physical activity is already reduced from GOLD Stage II,Citation2 which suggests that patients spontaneously choose to reduce their activity rather than be restricted by pulmonary limitation, which implies a possible behavioral component that can be influenced.

The present study showed associations between health and quality of life and the factors of social support and absence of economic problems, in line with data reported from general population surveys.Citation14 Among older persons with chronic diseases the highest risk for feelings of loneliness is reported for those with lung diseases.Citation27

There was a significant association between health, EQ-5D, and teetotalism. This is surprising as there are known relations between smoking and alcohol use,Citation28 which could be expected to influence health measures in subjects with COPD. The absence of some expected associations could also be interpreted as subjects with COPD, already having the status of limited health and quality of life, were not influenced by additional factors such as alcohol use.

Smoking was common among the subjects with COPD, where 28% smoked daily. This was a high number compared with smoking in the adult population in Sweden; 11% of men and 13% of women are daily smokers.Citation29 Thus, there are possibilities to reduce the prevalence of this important risk factor for subjects with COPD. Nonsmoking is a health supporting factor, but there is a worrying trend of higher prevalence of smoking among women, especially in younger age groups.Citation30

The design of the present study was cross-sectional and therefore no causal associations could be verified. Compared with studies directly aimed at subjects with respiratory symptoms, this population survey did not contain questions on specific respiratory symptoms, nor were there any instruments enabling grading severity of disease. The response rate in the present study was approximately 65%–70%, with a possible underestimation of smoking habits according to a study of nonresponders in a large scale questionnaire survey on respiratory health in Sweden.Citation31 There are, however, no signs of bias in disease and symptom prevalence in that study.

The prevalence of self-reported COPD in the present study was low compared with other studies.Citation32 The questionnaire did not focus on respiratory problems, however. Moreover, on the diagnosis list, the COPD diagnosis was, perhaps, not the primary diagnosis of choice. This could indicate that subjects with more severe disease, where a COPD diagnosis was clearly expressed, were included in the present study. The high proportion of retired persons or persons on sick leave also supported this assumption. It cannot be stated that our results could be generalized to the total COPD population.

The global perception of health status was, in our study, measured by one question according to the same principle as in other studies.Citation33 Idler et al conclude that self-ratings provide the respondents’ views of global health status in a way that nothing else can.Citation34 Regarding “Patient activity in COPD”, Paul W Jones suggests in a review that activity limitation may be a central determinant of impaired quality of life due to poor health,Citation35 which also implies an association between activity and health. Quality of life in chronic diseases varies between individuals and within an individual over time and can be described as “the discrepancy between our expectations and our experience”.Citation36 Montes de Oca et al report that an important proportion of persons with COPD grade their general health as good-to-excellent, and interpret this as “the patients’ underestimation of disease severity”.Citation33 This could, however, be a result of chronically ill patients’ adaptation to irreversible changes in their health through lower expectations of quality of life.Citation37

Conclusions

A better self-rated health status and quality of life was associated with higher levels of physical activity, social support, absence of economic problems, and never smoking. The findings indicated that of factors that can be influenced, the promotion of physical activity and the strengthening of social support are important to maintain or improve health and quality of life in subjects with COPD. Severity of the disease as a possible confounding effect should be investigated in future population studies.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a research grant from the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation, the Swedish Heart and Lung Association, and the County Council of Värmland.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflict of interest in this work.

References

- HalbertRJNatoliJLGanoABadamgaravEBuistASManninoDMGlobal burden of COPD: systematic review and meta-analysisEur Respir J200628352353216611654

- Executive Summary: Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD Available at: http://www.goldcopd.org/Accessed July 15, 2011

- RennardSDecramerMCalverleyPMImpact of COPD in North America and Europe in 2000: subjects’ perspective of Confronting COPD International SurveyEur Respir J200220479980512412667

- AntonovskyAHealth, Stress, and Coping1st edSan Francisco, CAJossey-Bass1979

- World Health OrganizationOttawa charter for health promotion; First International Conference on Health Promotion Available at: http://www.who.int/hpr/NPH/docs/ottawa_charter_hp.pdfAccessed July 15, 2011

- EjlertssonGEdenLLedenIPredictors of positive health in disability pensioners: a population-based questionnaire study using Positive Odds RatioBMC Public Health200222012225618

- ErikssonMLindstromBAntonovsky’s sense of coherence scale and its relation with quality of life: a systematic reviewJ Epidemiol Community Health2007611193894417933950

- ArneMJansonCJansonSPhysical activity and quality of life in subjects with chronic disease: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease compared with rheumatoid arthritis and diabetes mellitusScand J Prim Health Care200927314114719306158

- van ManenJGBindelsPJDekkerFWThe influence of COPD on health-related quality of life independent of the influence of comorbidityJ Clin Epidemiol200356121177118414680668

- Al-ShairKDockryRMallia-MilanesBKolsumUSinghDVestboJDepression and its relationship with poor exercise capacity, BODE index and muscle wasting in COPDRespir Med2009103101572157919560330

- MiravitllesMLlorCNaberanKCotsJMMolinaJVariables associated with recovery from acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespir Med200599895596515950136

- MackenbachJPBosJVDJoungIMAVan De MheenHStronksKThe determinants of excellent health: different from the determinants of ill-health?Int J Epidemiol1994236127312817721531

- CelliBRMacNeeWStandards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paperEur Respir J200423693294615219010

- MolariusABerglundKErikssonCSocioeconomic conditions, lifestyle factors, and self-rated health among men and women in SwedenEur J Public Health200617212513316751631

- McDowellINewellCMeasuring Health : A Guide to Rating Scales and Questionnaires2nd edNew YorkOxford University Press1996

- BurstromKJohannessonMDiderichsenFSwedish population health-related quality of life results using the EQ-5DQual Life Res200110762163511822795

- WilliamsRGeneralized ordered logit/partial proportional odds models for ordinal dependent variablesStata Journal2006615882

- KoenkerRQuantile regressionCambridge, UKCambridge University Press2005

- RoystonPSauerbreiWMultivariable model-building: a pragmatic approach to regression analysis based on fractional polynomials for modelling continuous variablesNew YorkJohn Wiley & Sons, Ltd2008

- Garcia-AymerichJLangePBenetMSchnohrPAntoJMRegular physical activity reduces hospital admission and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population based cohort studyThorax200661977277816738033

- Garcia-AymerichJSerraIGómezFPPhysical Activity and Clinical and Functional Status in COPDChest2009136627019255291

- DograSBakerJPhysical activity and health in Canadian asthmaticsJ Asthma2006431079579917169834

- PittaFTroostersTSpruitMAProbstVSDecramerMGosselinkRCharacteristics of physical activities in daily life in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2005171997297715665324

- NelsonMERejeskiWJBlairSNPhysical activity and public health in older adults: recommendation from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart AssociationMed Sci Sports Exerc20073981435144517762378

- ChavannesNHGrijsenMvan den AkkerMIntegrated disease management improves one-year quality of life in primary care COPD patients: a controlled clinical trialPrim Care Respir J200918317117619142557

- WatzHWaschkiBMeyerTMagnussenHPhysical activity in patients with COPDEur Respir J200933226227219010994

- PenninxBWJHvan TilburgTKriegsmanDMWBoekeAJPDeegDJHvan EijkJTMSocial network, social support, and loneliness in older persons with different chronic diseasesJ Aging Health199911215116810558434

- FalkDEYiHYHiller-SturmhofelSAn epidemiologic analysis of co-occurring alcohol and tobacco use and disorders: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related ConditionsAlcohol Res Health200629316217117373404

- [Tobaksvanor] Available at: http://www.fhi.se/en/Accessed July 15, 2011. Swedish

- AliSMChaixBMerloJRosvallMWamalaSLindstromMGender differences in daily smoking prevalence in different age strata: A population-based study in southern SwedenScand J Public Health200937214615219141546

- RönmarkEPEkerljungLLötvallJTorénKRönmarkELundbäckBLarge scale questionnaire survey on respiratory health in Sweden: Effects of late- and non-responseRespir Med2009103121807181519695859

- LindbergABjergARönmarkELarssonLLundbäckBPrevalence and underdiagnosis of COPD by disease severity and the attributable fraction of smoking Report from the Obstructive Lung Disease in Northern Sweden StudiesRespir Med2006100226427215975774

- Montes de OcaMTálamoCHalbertRJHealth status perception and airflow obstruction in five Latin American cities: The PLATINO studyRespir Med20091031376138219364640

- IdlerELBenyaminiYSelf-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studiesJ Health Soc Behav199738121379097506

- JonesPWActivity limitation and quality of life in COPDCOPD20074327327817729072

- CarrAJGibsonBRobinsonPGMeasuring quality of life: is quality of life determined by expectations or experience?BMJ2001322729612401243

- Voll-AanerudMEaganTMLWentzel-LarsenTGulsvikABakkePSRespiratory symptoms, COPD severity, and health related quality of life in a general population sampleRespir Med2008102339940618061422