Abstract

Background and objective

In recent years, the so-called asthma–chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) overlap syndrome (ACOS) has received much attention, not least because elderly individuals may present characteristics suggesting a diagnosis of both asthma and COPD. At present, ACOS is described clinically as persistent airflow limitation combined with features of both asthma and COPD. The aim of this paper is, therefore, to review the currently available literature focusing on symptoms and clinical characteristics of patients regarded as having ACOS.

Methods

Based on the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, a systematic literature review was performed.

Results

A total of 11 studies met the inclusion criteria for the present review. All studies dealing with dyspnea (self-reported or assessed by the Medical Research Council dyspnea scale) reported more dyspnea among patients classified as having ACOS compared to the COPD and asthma groups. In line with this, ACOS patients have more concomitant wheezing and seem to have more cough and sputum production. Compared to COPD-only patients, the ACOS patients were found to have lower FEV1% predicted and FEV1/FVC ratio in spite of lower mean life-time tobacco exposure. Furthermore, studies have revealed that ACOS patients seem to have not only more frequent but also more severe exacerbations. Comorbidity, not least diabetes, has also been reported in a few studies, with a higher prevalence among ACOS patients. However, it should be acknowledged that only a limited number of studies have addressed the various comorbidities in patients with ACOS.

Conclusion

The available studies indicate that ACOS patients may have more symptoms and a higher exacerbation rate than patients with asthma and COPD only, and by that, probably a higher overall respiratory-related morbidity. Similar to patients with COPD, ACOS patients seem to have a high occurrence of comorbidity, including diabetes. Further research into the ACOS, not least from well-defined prospective studies, is clearly needed.

Keywords:

Introduction

The obstructive lung diseases (OLDs), asthma, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are common and are associated with substantial morbidity. Both diseases are characterized by airflow limitation and chronic airway inflammation.Citation1–Citation3 In asthma, the airflow limitation is, similar to the symptoms, variable and in most cases reversible either spontaneously or following treatment, eg, in response to a bronchodilator.Citation1,Citation4 In contrast, the airflow limitation in COPD is, by definition, persistent and often progressive and may be associated with chronic cough and sputum production, and, with increasing severity, also exacerbations and comorbidities.Citation2 However, when examining an individual patient with symptoms of OLD, it may be difficult to reach a final diagnosis, especially in the elderly, because patients may present features characteristic for both asthma and COPD.Citation5–Citation7

So far the important question remains largely unanswered whether the overlap between asthma and COPD represent patients with coexisting asthma and COPD or a unique disease entity. Some publicationsCitation8,Citation9 emphasize that the asthma– COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS) should be regarded as an independent disease entity, although no agreement on definition has been reached so far.Citation10 In a Spanish consensus paper from 2012,Citation11 the participating specialists in pulmonary medicine agreed upon criteria for the “overlap phenotype COPD-asthma” and accepted it as a unique clinical phenotype. Furthermore, the Spanish consensus paperCitation11 and the very recently published Finnish COPD guidelinesCitation12 point, similar to a study by Kitaguchi et alCitation13 to paraclinical findings suggesting eosinophil airway inflammation, including higher peripheral and sputum eosinophil counts and elevated exhaled nitric oxide in patients with ACOS or asthma-like COPD.Citation13,Citation14

The outcome of a very recent collaboration between the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) and Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) are dealing with a clinical description of ACOS.Citation5 The document describes the syndrome as having shared features with both asthma and COPD together with nonreversible airflow limitation, although at the same time emphasizing that the document is intended only for clinical work and not to be used as a definition of ACOS.Citation5

The proportion of patients suffering from OLD that may be classified as having ACOS varies between studies, depending on the definition, but in recent publications, it has been estimated to be 15%–25%.Citation14–Citation18 Further knowledge, not least with regard to clinical characteristics and risk factors,Citation18–Citation22 of ACOS is, therefore, clearly needed and might lead to a generally accepted definition.

The objective of this paper is to review the current knowledge of clinical characteristics of patients regarded as having ACOS.

Methods

Search strategy

The general principles of the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelinesCitation23 were adopted to perform this review. A series of systematic searches were carried out, last updated May 2015, on the databases PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, and Clinical Trials.gov. The strategy was to assemble as much literature about the ACOS as possible. In order to do so, the search algorithm consisted of whole words, short terms, and exact chosen order of words (using of “” symbols) combined with MeSH terms, and the searches were therefore carried out using the following algorithm: (asthma OR “asthma” OR “asthma” [MeSH Terms]) AND (COPD OR “COPD” OR “chronic obstructive pulmonary disease” OR “pulmonary disease, chronic obstructive” [MeSH Terms]) AND (“overlap syndrome” OR “asthma COPD overlap syndrome” OR “overlap phenotype”) AND (definition OR diagnosis OR clinical characteristics OR clinical features OR clinical outcomes OR phenotypes OR risk factors OR treatment OR drug therapy OR health impairment).

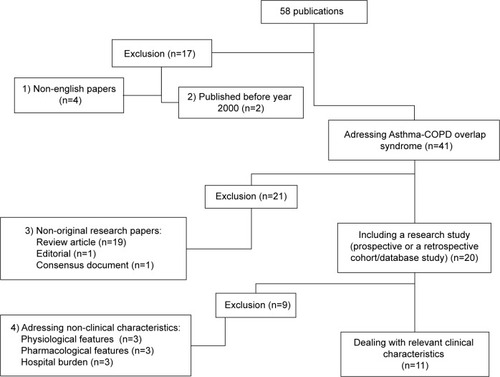

Publications were included in the present review if they fulfilled the following inclusion criteria: 1) reporting observations from a specific study/survey, 2) being a prospective or a retrospective cohort/database study, and 3) reporting characteristics and findings about the group of ACOS patients and/or comparing ACOS with asthma and/or COPD, and none of the following exclusion criteria: 1) manuscripts published in a language other than English, 2) published before year 2000, 3) nonoriginal research paper, eg, reviews, and 4) addressing nonclinical characteristics, including physiological or pharmacological features (). A meta-analysis was not included in the present review, primarily due to the limited number of published studies fulfilling the inclusion criteria.

Results

The searches identified 58 publications, of which a total of eleven papers fulfilled the criteria and were included in the present review, and further details of the included studies are given in .

Table 1 Characteristics with regard to design and methods, sample size, proportion, and definition of patients regarded as having the asthma–COPD overlap syndrome, and comparison groups for the studies (n=11) included in the present review

Definition of ACOS

As no generally accepted definition of ACOS has been reached yet, studies included in the present review have applied different definitions, and details of these definitions are given in .

Briefly, Brzostek and KokotCitation20 defined ACOS as a mixed phenotype with a combination of features of both asthma and COPD. Chung et alCitation24 defined it as an FEV1/FVC ratio <0.7 plus a history of self-reported wheeze, whereas de Marco et alCitation8 defined it as having a self-reported physician diagnosis of both asthma and COPD (defined as a diagnosis of COPD, emphysema, or chronic bronchitis). Apart from having respiratory symptoms, patients classified as having ACOS in the study by Fu et alCitation25 were required to have increased airflow variability, defined as airway hyperresponsiveness or bronchodilator reversibility, and not fully reversible airflow obstruction (ie, postbronchodilator [post-BD] FEV1/FVC <0.7 and post-BD FEV1 <80% of predicted).

In the study by Hardin et alCitation26 overlap subjects were defined as COPD patients with self-reported physician diagnosed asthma before the age of 40 years, and in the study by Kauppi et alCitation18 they were defined as patients having both a diagnosis of asthma and COPD, where asthma was defined according to the GINA guidelinesCitation1 and COPD according to the GOLD strategy document.Citation27

In a retrospective cohort study, Lee et alCitation28 defined ACOS patients as having asthma (defined as a bronchodilator reversibility test with an increase in FEV1 of >200 mL and 12%, and/or positive metacholine/mannitol challenge test) together with a post-BD FEV1/FVC <0.70 at the initial assessment, and continuing airflow obstruction after at least 3 months follow-up, irrespective of treatment. Menezes et alCitation29 classified patients as having ACOS if they fulfilled the criteria for both asthma, ie, wheezing in the last 12 months plus post-BD increase in FEV1 (200 mL and 12%) or a self-reported doctor diagnosis of asthma and COPD, ie, post-BD FEV1/FVC <0.7.

Milanese et alCitation7 classified overlap patients as subjects ≥65 years with physician diagnosis of asthma (defined according to the GINA guidelines 2012) plus chronic bronchitis, ie, chronic mucus hypersecretion or/and impaired diffusion capacity, ie, total diffusion capacity <80% of the predicted value, whereas Miravitlles et alCitation22 classified ACOS patients on the basis of a post-BD FEV1/FVC <0.7 together with physician diagnosis of asthma before the age of 40 years. Pleasants et alCitation30 defined ACOS as answering affirmatively to questions about a physician diagnosis of both COPD and asthma.

Symptoms

Brzostek and KokotCitation20 published an analysis of data from 12,103 smoking patients (mean tobacco exposure 28.4 pack-years) aged >45 years (mean age, 61.5 years), enrolled over a period of 18 months. The aim was to identify the typical phenotype of patients classified as having ACOS, receiving specialist pulmonary care. Each of the 384 participating pulmonary specialists completed the questionnaires for up to 32 patients based on the patients’ medical records and paraclinical history. Patients were included if they had, either presently or in their past medical history, features of both asthma and COPD, and therefore, no control group was included in the study. A total of 68% of the patients had exertional dyspnea, interpreted as a COPD feature, whereas 63% had paroxysmal dyspnea with wheezing, interpreted as an asthma feature. Furthermore, 72% of the patients had chronic productive cough, also regarded as a COPD feature.

A retrospective study by Pleasants et alCitation30 analyzed data obtained by questionnaires as part of the “Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey” in North Carolina in 2007 and 2009, where data were sampled by household telephone calls and included questions about asthma and COPD. The final population sample comprised 24,073 individuals (aged 18–74 years), and all individuals were divided into the following groups: former asthma, current asthma, COPD, no obstructive lung disease (NOD), and ACOS. A total of 807 patients were classified as having the ACOS. The prevalence of shortness of breath (SOB) having impact on quality of life was significantly higher in the ACOS group compared to the COPD group (SOB 76% [95% confidence interval [CI]: 68–84] vs 57% [49–64], P<0.05). SOB was not assessed in the asthma group.

Miravitlles et alCitation22 analyzed data concerning COPD patients from an epidemiological, cross-sectional, population-based study in Spain (the EPI-SCAN study). The study included 3,885 noninstitutionalized individuals (aged 40–80 years) who filled in questionnaires and had lung function and walking distance measured (), and the study was conducted at eleven centers throughout Spain. A total of 385 subjects were classified as having COPD, and 67 of these patients were classified as having overlap features. The authors reported that the overlap group had a higher prevalence of dyspnea compared to the COPD group (P<0.001). Patients with the overlap phenotype were also more likely to report wheezing compared to the COPD group (92.5% vs 58.2%, P<0.001). On the contrary, the proportion of patients reporting cough and sputum production did not differ between the asthma–COPD overlap patients and COPD patients.

In contrast to the observations reported from the study by Miravitlles et alCitation22 the cross-sectional study by Menezes et alCitation29 identified the highest prevalence of cough and phlegm in the ACOS group (P<0.001). The authors analyzed data from the “Latin American Project for the Investigation of Obstructive Lung Disease”, ie, a multicenter population-based survey with a sample of 5,044 individuals, who completed questionnaires and had spirometry performed. A total of 89 subjects were classified as suffering from ACOS, whereas the remaining subjects were assigned to one of the groups: COPD, asthma, or NOD. Additionally, Menezes et alCitation29 reported that the asthma group had a higher prevalence of dyspnea (P<0.001). Wheezing was equally reported by all patients with asthma (100%) and overlap syndrome (100%), whereas it was reported significantly less by patients with COPD (29%, P<0.001).

Milanese et alCitation7 analyzed data from an Italian observational study, ie, the “Elderly Subjects with Asthma study”, performed in 16 Italian pulmonology and allergy clinics. A total of 350 elderly asthmatics (≥65 years) were enrolled over 6 months in 2012–2013, and 101 patients were classified as having ACOS based on questionnaires and objective tests. Milanese et alCitation7 concluded that a total of 84% of the ACOS subjects reported chronic bronchitis. The ACOS group also had a higher Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnea score compared to the asthma group (P<0.010). The above-mentioned study by Miravitlles et alCitation22 reported similar observations, when comparing MRC scores in the ACOS group with the COPD group (P<0.008).

An Italian cross-sectional study by de Marco et alCitation8 included a population sample of 8,360 individuals (aged 20–84 years) participating in the multicenter “Gene Environment Interaction in Respiratory Diseases study” (GEIRD), where eligible subjects were randomly selected from the local health authority register at four Italian clinical GEIRD centers. The subjects received questionnaires by mail or phone (with a response rate of 50%) and were subsequently assigned to one of four groups: asthma, COPD, asthma– COPD overlap, or NOD. de Marco et alCitation8 observed a higher prevalence of MRC dyspnea scores ≥3 in the ACOS group (39% [31–47]) compared to the COPD group (21% [17–25]) and asthma group (9% [7–12]). de Marco et alCitation8 also reported that the overlap group were more likely to have cough/phlegm (overlap: 62% [95% CI 54–69], COPD: 54% [49–59], asthma: 23% [20–27]) and wheezing (overlap: 79% [71–85], COPD: 43% [38–48], asthma: 43% [39–48]). In contrast, the subjects in the asthma group had the highest prevalence of rhinitis (asthma: 59 vs overlap: 53%, P<0.001). The authors concluded that the subjects with concomitant asthma and COPD were more likely than subjects with only asthma or COPD to have physical limitations, although based only on the MRC dyspnea score.

Exercise capacity

A cross-sectional study by Hardin et alCitation26 based on data from the large multicenter observational “COPD Gene study”, which is a prospective cohort study of more than 10,000 smokers enrolled by 21 clinical study centers across the USA between January 2008 and June 2011, analyzed the cross-sectional questionnaire and spirometry data. In this study, a total of 3,570 subjects with COPD (aged 45–80 years) were identified, of whom 450 subjects were classified as having the ACOS. The BODE index (ie, Body mass index, airflow Obstruction, Dyspnea and Exercise capacity) was applied for evaluation of the enrolled patients.Citation31 The BODE score was significantly higher in the ACOS group (3.1±2.0) compared to the COPD patients (2.9±2.1; P<0.02), although the difference did not at all approach the minimal clinical important difference.Citation26

A cohort follow-up study by Fu et alCitation25 comprised 99 OLD patients (>55 years) from an Australian hospital, of whom 55 were classified as having ACOS. The assessments were based on questionnaires, spirometry, and exercise capacity at baseline and at the 4-year follow-up (from 2006/2007 to 2011). No significant difference was observed in 6 minutes walking distance (6MWD) between patients with asthma, COPD, and ACOS (asthma 429 m ±94, COPD 409 m ±105, overlap 405 m ±110, P=0.8). Addressing longitudinal changes, the decline over the 4 years in exercise capacity, assessed by the 6MWD, was less pronounced in the ACOS group compared to the COPD group (P<0.05). In line with this, the study by Miravitlles et alCitation22 did not reveal differences in 6MWD and physical activity between overlap patients and COPD only patients.

Other paraclinical findings

A retrospective study by Lee et alCitation28 reviewed medical records of 256 patients with asthma (aged 41–79 years), all diagnosed at a Korean hospital between 2007 and 2012. The analyzed data included spirometry, eosinophil counts, and total IgE. A total of 97 of the asthma patients were classified as having ACOS based on the above-mentioned definition. The authors found no significant difference in airway hyperresponsiveness or bronchodilator responsiveness between the two groups. However, they did observe that the ACOS group had significantly lower serum eosinophil count (ACOS: 267.8 cells/μL ±32.7 vs 477.5 cells/μL ±68.9, P=0.02) and higher total IgE (ACOS: 332.1 U/mL ±74.0 vs 199.8 U/mL ±33.4, P=0.03) compared to the asthma group. Yet, there was no significant difference in the proportion of subjects with a positive skin prick test between the groups.

Lung function

The observations regarding lung function parameters are given in .

Table 2 Spirometric parameters among patients classified as ACOS, COPD only, and asthma only

Chung et alCitation24 analyzed data from the cross-sectional Fourth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination (KNHANES IV) Survey (2007–2009). They included a population sample of 9,104 noninstitutionalized individuals (>19 years). The subjects completed questionnaires on respiratory symptoms and comorbidities and performed spirometry (exclusion criteria are listed in ). A total of 210 subjects were classified as asthma–COPD overlap patients, whereas the remaining subjects were classified as having asthma, COPD, or NOD. The ACOS subjects had significantly lower level of lung function (FEV1% predicted, FVC% predicted, and FEV1/FVC) compared to the asthma and COPD group. Findings in keeping with this have been reported from the studies by Menezes et alCitation29 and Milanese et al.Citation7

Brzostek and KokotCitation20 observed that 79% of the enrolled ACOS patients had persistent lung function impairment, that is, post-BD FEV1 <80% predicted. Chung et alCitation24 reported that among patients assigned to the ACOS group, 61% had a FEV1% predicted between 50 and 80, and 12% of ACOS patients had an FEV1% predicted <50. This proportion of patients with poor FEV1 (<50% predicted) in the ACOS group was higher compared to the asthma group (<1%) and COPD group (4%).

Between 2005 and 2007, Kauppi et alCitation18 enrolled 546 patients (aged 18–75 years), discharged from a Finnish hospital in the time period of 1995–2006, with a diagnosis of asthma, COPD, or both. At enrollment, the clinical data were obtained from medical records, including spirometry. All patients filled in questionnaires initially and thereafter at annual follow-up visits for 10 years. Two-hundred and twenty-five patients were classified as overlap patients according to the above-mentioned definition. Compared to the COPD and asthma groups, the overlap group had in between values for FEV1% predicted, FVC% predicted, and FEV1/FVC (expressed as mean ± standard deviation).

Fu et alCitation25 reported more pronounced baseline airflow obstruction in the ACOS group and COPD group compared to the asthma group (), but observed no significant difference between the COPD group and overlap group. There was a significant decline over time in FEV1 in all groups, but no significant differences between the three groups.

The overlap group in the study by Lee et alCitation28 had higher total lung capacity (111%±2% vs 102%±2%, P<0.01), functional residual capacity (125%±4% vs 102%±2%, P<0.01), and residual volume (126%±6% vs 99%±4%, P<0.01) compared to the patients with asthma.

Exacerbations

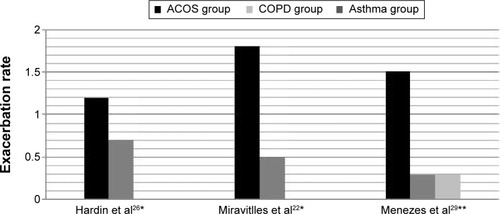

Hardin et al,Citation26 Miravitlles et al,Citation22 and Menezes et alCitation29 have all reported on exacerbations in patients classified as having ACOS. As shown in , they all observed a higher frequency of exacerbations in the ACOS group compared to the COPD group (and also compared to the asthma group in the study by Menezes et alCitation29). shows a similar tendency, with ACOS having the highest prevalence of exacerbations. After adjusting for age, sex, BMI, education, comorbidity score, pack-years, and reported use of any inhaled therapy (bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids), Menezes et alCitation29 found that the overlap syndrome was still associated with a higher risk for exacerbations.

Table 3 Prevalence (P) and prevalence ratio (PR) of exacerbations among patients classified as having ACOS and comparison groups

Figure 2 Frequency of exacerbations (per year) among patients classified as ACOS, COPD only, and asthma only.

Abbreviations: ACOS, asthma–chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap syndrome; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The focus of Hardin et alCitation26 was severe exacerbations, defined as a history of exacerbations that resulted in an emergency room visit or hospital admission. Milanese et alCitation7 assessed severe exacerbations, defined as an exacerbation requiring a rescue course of systemic corticosteroids for at least 3 days and/or hospitalization. They observed that more ACOS subjects experienced both 1 and ≥2 severe exacerbations compared to asthma subjects (). Brzostek and KokotCitation20 observed that 69% of the enrolled ACOS patients had exacerbations over the past year, with a mean number of 2.1±1.8 exacerbations in the last year.

Additionally, Menezes et alCitation29 observed a higher prevalence of hospitalizations in the ACOS group compared to COPD and asthma groups (overlap, 5.6%; COPD, 1.2%; asthma, 0%; P<0.003). However, the prevalence of patients with exacerbation requiring a visit to the doctor was similar in the asthma group and overlap group (asthma, 11.9%; COPD, 4.0%; overlap, 11.2%; P<0.001). Similar findings with regard to the prevalence of hospitalization are reported by de Marco et alCitation8 (overlap, 3.1% [1.4–6.7]; asthma, 1.1% [0.5–2.4]; COPD, 2.5% [1.4–4.5]; P=0.001) (adjusted for sex, age, season, % of answers to the questionnaire, type of survey (postal/telephone), and clinical center).

Comorbidity

In the study by Brzostek and Kokot,Citation20 concomitant diseases were diagnosed in 85% of the enrolled patients. The mean number of comorbidities (including arterial hypertension, allergic rhinitis, ischemic heart disease, reflux disease, type 2 diabetes, heart failure, obesity, osteoporosis, metabolic syndrome) was 2.6, indicating that the patients mostly had more than one concomitant disease. A total of 63% of the ACOS patients had arterial hypertension, and 46% had metabolic disorders, ie, diabetes, obesity, and metabolic syndrome.

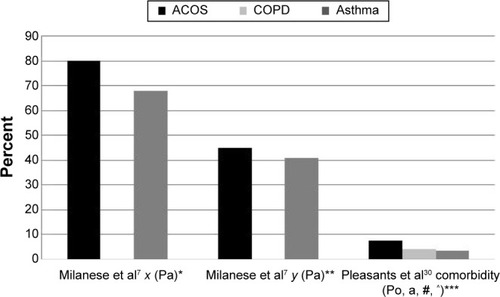

Details of the studies reporting on the prevalence of comorbidity in ACOS patients compared to patients with asthma and COPD are given in . Pleasants et alCitation30 observed that ACOS patients had the highest age-adjusted prevalence of self-reported doctor diagnosed diabetes, coronary heart disease, stroke, arthritis, and high blood pressure. Yet, compared to the asthma and COPD patients, the differences only reached statistical significance for diabetes (), stroke, and arthritis. Additionally, Chung et alCitation24 reported that ACOS patients were more likely to have past or concomitant respiratory diagnoses, such as pulmonary tuberculosis and bronchiectasis.

Figure 3 Prevalence of comorbidities among patients classified as ACOS, COPD only, and asthma only.

Notes: x, proportion having a comorbid condition; y, having two comorbid conditions; Pa, patient study, where comorbidities were inferred by recording concomitant drug prescriptions for other diseases (arterial hypertension, chronic heart disease, diabetes, gastroesophageal and osteoporosis); Po, population study with self-reported comorbidities; a, age adjusted (≥18 years). #Data from the comorbid condition; stroke is chosen to give a representative impression of tendency in the study, in the lack of data about all comorbidities together. ^Asthma group only includes patients with current asthma. *P<0.02, **P<0.633, ***P<0.05.

Abbreviations: ACOS, asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap syndrome; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

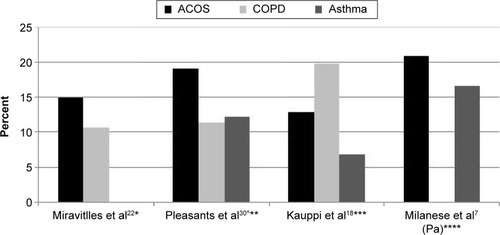

Figure 4 Prevalence of the comorbidity diabetes in patients classified as having ACOS, COPD* only, and asthma only.

Abbreviations: ACOS, asthma–chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap syndrome; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

In contrast, in the study by Milanese et alCitation7 the proportion of patients with two or more comorbidities did not differ significantly between the asthma and overlap group. The presence of comorbidity was defined based on the drugs being prescribed (obtained from the patients’ medical records). Significant more patients in the ACOS group were prescribed treatment for arterial hypertension (66%) compared to patients with asthma (53%) (P<0.024), but the data were not adjusted for age. However, no significant differences were observed between the groups with regard to prescribed treatment for other comorbidities.

illustrates the proportion of subjects from each group, ie, ACOS, COPD, and/or asthma, with concomitant diabetes. Among the different comorbidities observed in the listed studies, ACOS is repeatedly associated with a higher prevalence of diabetes. Pleasants et al,Citation30 Miravittles et al,Citation22 and Milanese et alCitation7 reported a higher proportions of ACOS subjects with concomitant diabetes compared to asthma and/or COPD subjects, although the difference did not reach statistical significance.

Addressing cardiovascular dysfunction as the only comorbid condition, Fu et alCitation25 found no significant differences between the ACOS, asthma, and COPD group. In the study by Kauppi et alCitation18 the prevalence of the six selected comorbidities (including diabetes) in the overlap group was in between values reported in the asthma and COPD group. The COPD group had the highest prevalence of all types of comorbidities. Yet, they did find statistical significant differences between the asthma, COPD and overlap group in cardiovascular disease (asthma, 7.7; overlap, 19.1; COPD, 25.3; P≤0.001).

Fu et alCitation25 and Miravittles et alCitation22 used the Charlson Comorbidity index (CCI) as a prognostic indicator for mortality among the enrolled patients. Fu et alCitation25 found no significant difference in CCI at baseline between the three groups (asthma, 3.5; COPD, 4; overlap, 4; P=0.82) and identified a significant increase in total CCI for all groups at follow-up. Miravittles et alCitation22 found that CCI was significantly higher for ACOS compared to COPD (overlap, 1.44 (0.78); COPD, 0.89 (1.07); P<0.001).Citation22 Yet, each comorbid condition taken individually, the difference was only significant for diabetes.

Discussion

The available studies suggest that ACOS patients have more dyspnea and wheezing compared to patients with only asthma or COPD,Citation7,Citation8,Citation22,Citation30 and some studies also report more cough and phlegm.Citation8,Citation29 Furthermore, studies have shown that ACOS patients have more frequent and possibly also more severe, exacerbations compared to patients with asthma or COPD.Citation7,Citation22,Citation26,Citation29 In line with this, a limited number of studies have reported a higher prevalence of comorbidities in ACOS patients compared to the COPD-only patients group, especially with regard to diabetes.Citation7,Citation22,Citation30

However, the inconsistence in the observations of the symptoms wheeze, cough, and sputum make it difficult to draw valid conclusions with regard to whether they are more prevalent in ACOS patients compared to asthma and COPD. The fact that Menezes et alCitation29 only assessed dyspnea as an affirmative response to question about dyspnea (), and not the MRC scale, may at least partly explain why they, in contrast to the other studies, did not find ACOS patients to have the highest prevalence of dyspnea.Citation7,Citation8,Citation22,Citation30 The different methods applied for assessment, for example, by Menezes et alCitation29 and Pleasants et alCitation30 asking about SOB impede the interstudy comparisons. The observation of a less pronounced longitudinal decline in 6MWD in ACOS patients by Fu et alCitation25 might be questioned due to the small sample size and the inclusion of patients classified as having COPD without any reported exposure to noxious particles or gasses.Citation2

A higher proportion of overlap patients with lung function impairment, defined as reduced FEV1% predicted, reported by Chung et alCitation24 may indicate a worse outcome for patients with ACOS. In the studies by Lee et alCitation28 and Milanese et alCitation7 the observations are very likely affected by the fact that their overlap groups include more smokers, as expected, than the asthma groups.Citation24

Even though the results of the studies point in the same direction to more exacerbations in ACOS, they are not easily compared. This is due to variability in the description and grade of exacerbations (ie exacerbations vs severe exacerbations) and which OLD (asthma, COPD, or both) ACOS is compared to ().

Many of the comorbidities observed in the studies are not common asthma comorbidities,Citation1 most likely due to the fact that patients with asthma on average are younger, but rather refer to the elderly population, such as stroke, arthritis, and to some extend diabetes. In addition, it is likely that smoking can be a confounder in the association between comorbidities and ACOS due to the number of smokers often being higher in the ACOS-group compared to patients with only asthma.

Milanese et alCitation7 speculates if the high proportion of exacerbations can be related to the reported high prevalence of comorbidities, and Chung et alCitation24 suggest that the ACOS is associated with higher morbidity, which may appear likely as comorbidities contributing to health impairment.Citation5,Citation20 With regard to the BODE score, the use and validation has been for COPD, but it has been proposed to be an effective prognostic tool in older adults with OLDs in general.Citation25 The higher BODE score in ACOS patients found by Hardin et alCitation26 cannot be used as an indication of a worse prognosis, due to the lack of clinical significant difference between ACOS and COPD. Regarding the study by Brzostek and Kokot,Citation20 comparison to the other studies of the review is not possible, owing to the fact that the data analyzed is only for subjects classified as having ACOS.

Taken as a whole, comparison of the eleven studies is hampered by the controversy about classifying patients into the OLD groups. The definition and fundamental for classifying a patient as having ACOS differs from being based on physiologically criteria, specific inclusion criteria, or just a presence of both asthma and COPD diagnoses. This is probably the most important limitation of this review and for the research of ACOS in general. In publications focusing on COPD, by having a cohort of COPD patients as the target population and classifying patients with asthma-like COPD as ACOS,Citation22,Citation26 the issue is that the proportion of COPD patients being classified as ACOS varies considerably owing to the various definitions. Another example is, in the study by Menezes et alCitation29 the data about an equally reporting of wheezing in all asthma only- and overlap patients can be doubted, because wheezing (in the last 12 months) is one of their criteria applied for asthma and is also a part of their ACOS definition (). The studies’ conclusion regarding ACOS having more dyspnea and more exacerbations may be interfered by the fact that the criteria belonging to the definitions cause the overlap group to comprise the sickest patients of the study population. For example, when defining ACOS as a combination of a diagnosis of asthma and COPD it is unclear if the most ill patients are handpicked, or the mutual features of these patients actually are an expression of the clinical characteristics of ACOS.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the current available studies suggest that patients with ACOS have more symptoms, more exacerbations, and also comorbidity compared to asthma- and COPD patients, which all are likely to indicate a worse outcome. Further evidence, including prospective longitudinal studies with more standardized outcome measures, is clearly needed.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- (GINA) GIfAThe Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention2014

- (GOLD) GIfCOLDGlobal Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD2014

- NakawahMOHawkinsCBarbandiFAsthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and the overlap syndromeJ Am Board Fam Med201326447047723833163

- PriceDBrusselleGChallenges of COPD diagnosisExpert Opin Med Diagn20137654355624099180

- Disease GIfAafCOLDiagnosis of Diseases of Chronic Airflow Limitation: Asthma COPD and Asthma-COPD Overlap Syndrome (ACOS) Based on the Global strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention and the Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention og COPD2014116 Available from http://www.ginasthma.org and www.goldcopd.org

- GibsonPGSimpsonJLThe overlap syndrome of asthma and COPD: what are its features and how important is it?Thorax200964872873519638566

- MilaneseMDi MarcoFCorsicoAGELSA Study GroupAsthma control in elderly asthmatics. An Italian observational studyRespir Med201410881091109924958604

- de MarcoRPesceGMarconAThe coexistence of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): prevalence and risk factors in young, middle-aged and elderly people from the general populationPLoS One201385e6298523675448

- MontuschiPMalerbaMSantiniGMiravitllesMPharmacological treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: from evidence-based medicine to phenotypingDrug Discov Today201419121928193525182512

- Al-KassimiFAAlhamadEHA challenge to the seven widely believed concepts of COPDInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20138213023378752

- Soler-CataluñaJJCosíoBIzquierdoJLConsensus document on the overlap phenotype COPD-asthma in COPDArch Bronconeumol201248933133722341911

- KankaanrantaHHarjuTKilpeläinenMDiagnosis and pharmacotherapy of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the finnish guidelines. Guidelines of the Finnish Medical Society Duodecim and the Finnish Respiratory SocietyBasic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol2015116429130725515181

- KitaguchiYKomatsuYFujimotoKHanaokaMKuboKSputum eosinophilia can predict responsiveness to inhaled corticosteroid treatment in patients with overlap syndrome of COPD and asthmaInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2012728328922589579

- BarrechegurenMEsquinasCMiravitllesMThe asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap syndrome (ACOS): opportunities and challengesCurr Opin Pulm Med2015211747925405671

- LouieSZekiAASchivoMThe asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap syndrome: pharmacotherapeutic considerationsExpert Rev Clin Pharmacol20136219721923473596

- ZekiAASchivoMChanAAlbertsonTELouieSThe asthma-COPD overlap syndrome: a common clinical problem in the elderlyJ Allergy20112011861926

- AndersenHLampelaPNevanlinnaASaynajakangasOKeistinenTHigh hospital burden in overlap syndrome of asthma and COPDClin Respir J20137434234623362945

- KauppiPKupiainenHLindqvistAOverlap syndrome of asthma and COPD predicts low quality of lifeJ Asthma201148327928521323613

- BramanSSThe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-asthma overlap syndromeAllergy Asthma Proc2015361111825562551

- BrzostekDKokotMAsthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap syndrome in Poland. Findings of an epidemiological studyPostepy Dermatol Alergol201431637237925610352

- MiravitllesMSoler-CataluñaJJCalleMA new approach to grading and treating COPD based on clinical phenotypes: summary of the Spanish COPD guidelines (GesEPOC)Prim Care Respir J201322111712123443227

- MiravitllesMSorianoJBAncocheaJCharacterisation of the overlap COPD-asthma phenotype. Focus on physical activity and health statusRespir Med201310771053106023597591

- LiberatiAAltmanDGTetzlaffJThe PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaborationJ Clin Epidemiol20096210e1e3419631507

- ChungJWKongKALeeJHLeeSJRyuYJChangJHCharacteristics and self-rated health of overlap syndromeInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2014979580425092973

- FuJJGibsonPGSimpsonJLMcDonaldVMLongitudinal changes in clinical outcomes in older patients with asthma, COPD and asthma-COPD overlap syndromeRespiration2014871637424029561

- HardinMChoMMcDonaldMLThe clinical and genetic features of COPD-asthma overlap syndromeEur Respir J201444234135024876173

- VestboJHurdSSAgustiAGGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summaryAm J Respir Crit Care Med2013187434736522878278

- LeeHYKangJYYoonHKClinical characteristics of asthma combined with COPD featureYonsei Med J201455498098624954327

- MenezesAMMontes de OcaMPérez-PadillaRPLATINO TeamIncreased risk of exacerbation and hospitalization in subjects with an overlap phenotype: COPD-asthmaChest2014145229730424114498

- PleasantsRAOharJACroftJBChronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma-patient characteristics and health impairmentCOPD201411325626624152212

- CelliBRCoteCGMarinJMThe body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2004350101005101214999112