Abstract

Aim:

This pilot study aimed to evaluate the individual features of the metabolic syndrome (MeS) and its frequency in Qatari schoolchildren aged 6–12 years.

Background:

MeS has a strong future risk for development of diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. Childhood obesity is increasing the likelihood of MeS in children.

Methods:

The associated features of MeS were assessed in 67 children. They were recruited from the outpatient pediatric clinic at Hamad Medical Corporation, Qatar. Height, weight, and waist circumference were measured and body mass index was calculated for each child. Fasting blood glucose, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides (TG) were measured. MeS was defined according to the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP-III) which was modified by Cook with adjustment for fasting glucose to ≥5.6 mM according to recommendations from the American Diabetes Association.

Results:

The overall prevalence of MeS according to NCEP-III criteria was 3.0% in children aged 6–12 years. Overweight and obesity was 31.3% in children aged 6–12 years, according to the International Obesity Task Force criteria. The prevalence of MeS was 9.5% in overweight and obese subjects. Increased TG levels represented the most frequent abnormality (28.4%) in metabolic syndrome features in all subjects, followed by HDL-C (19.4%) in all subjects.

Conclusion:

Increased TG levels and low HDL-C were the most frequent components of this syndrome. This study showed a significant prevalence of MeS and associated features among overweight and obese children. The overall prevalence of MeS in Qatari children is in accordance with data from several other countries.

Introduction

Several studies have demonstrated that cardiovascular diseases (CVD) begin early in childhood and atherosclerotic changes may occur early in the life of children with lipid abnormalities.Citation1,Citation2 Metabolic syndrome (MeS) clusters consist of obesity, insulin resistance, hypertension, impaired glucose tolerance, hyperinsulinemia and dyslipidemia associated with low high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and hypertriglyceridemia.Citation3

Childhood obesity is increasing worldwide including in Qatar,Citation4,Citation5 thus increasing the likelihood of MeS in children.Citation6 Physicians need to screen and detect early manifestations of MeS clusters during childhood, particularly among obese children.

The State of Qatar is a small country in the Arab Gulf area. Data relevant to MeS are limited among Qatari schoolchildren, therefore this study aimed to investigate the frequency of MeS and its associated features in 6 to 12 year old Qatari children.

Methods

This cross-sectional study involved a total of 67 subjects aged 6–12 years (30 males and 37 females). A convenient sample was recruited from the pediatric outpatient clinic at Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC), Qatar, from March 2005 to August 2005. The study was approved by the Research Ethics committee of HMC and informed consent was obtained.

Body weight was measured, using a Seca 634 digital electronic platform scale (Birmingham, UK) with precision to 0.1 kg, following a standardized procedure (lightly dressed, without shoes). Standing height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm with the use of a stadiometer. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight in kg by height squared in meters. Waist circumference (WC) was measured in duplicate by means of a nonelastic flexible tape, with subjects standing, at the smallest abdominal position between the iliac crest and the lower rib margin at the end of normal expiration. The measurements were recorded to the nearest 0.5 cm. Blood pressure (BP) was measured in triplicate on the arm with the patient seated after rest, using a digital sphygmomanometer and appropriate sized cuff. A fasting blood sample was drawn. Blood glucose, total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) were determined as previously published.Citation7

MeS was defined according to the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP-III)Citation8 which was modified by Cook,Citation9 with adjustment for fasting glucose to ≥5.6 mM according to American Diabetes Association recommendations.Citation10 MeS required the presence of 3 components out of 5 of the following criteria:

Abdominal obesity with waist circumference ≥90th percentile for age/gender, according to previous studies.Citation9,Citation11 A recent study evaluating the waist circumference reference values for screening cardiovascular risk factors in Chinese children and adolescents aged 7–18 years, indicated a slight increasing trend of cardiovascular risk factors starting from the 75th percentile of waist circumference in the study population, while a significant increasing trend occurred from the 90th percentile.Citation12

Impaired fasting glucose (glucose ≥ 5.6 mM).

Systolic/diastolic blood pressure (≥90th percentile for height, age, and gender).

TG ≥ 1.24 mM.

HDL-C ≤ 1.036 mM or below the 5th percentile.

The International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) criterion was adopted for classification of children as overweight and obese.Citation13

Statistical analysis

Statistical evaluation was performed with SPSS, PC (program for Windows, version 19, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Student’s t-test was used for comparison between groups. Comparisons of frequencies of individual components and the numbers of MeS were performed using the Chi-Square test. A level of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The anthropometric, clinical, and biochemical characteristics of the 67 children are presented by gender in . Boys had a statistically significant higher value for TG than girls. Using IOTF, 10 boys (14.9%) and 11 girls (16.4%) were overweight and obese.

Table 1 Descriptive characteristics of a sample of Qatari school children 6 to 12 years-old by gender

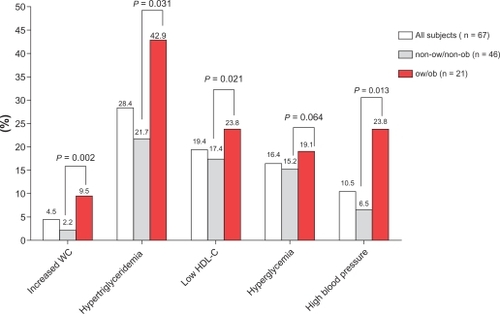

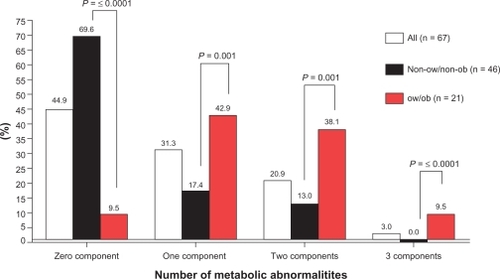

and present the individual components of MeS by gender and overweight and obesity status. Hypertriglyceridemia was the most frequent component of MeS (28.4%) among all subjects, and was significantly higher among boys than girls. The second order of frequency among MeS components was low HDL-C (19.4%), followed by hyperglycemia (16.4%), then hypertension (10.5%) and lastly by abdominal obesity (4.5%). The overall incidence of MeS among all children was 3.0%. The two subjects presenting with MeS were obese. The number of components of MeS was higher in boys than girls, (33.3% versus 29.7%), (30.0% versus 13.5%) and (3.3% versus 2.7%) for one, two and three components respectively. The number of components of MeS was significantly higher in overweight and obese children than non-overweight and non-obese children, (42.9% versus 17.4%), (38.1% versus 13.0%) and (9.5% versus 0.0%) for one, two and three components respectively ().

Figure 1 Frequency of individual MeS components (%) in all subjects and according to overweight/obesity status.

Abbreviations: WC, waist circumference; MeS, metabolic syndrome; ow and ob, overweight and obese; non-ow and non-ob, non-overweight and non-obese; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Figure 2 The frequency of clustering of metabolic abnormalities among Qatari school children aged between 6 and 12 years according to overweight/obesity status.

Abbreviations: ow and ob, overweight and obese; non-ow and non-ob, non-overweight and non-obese.

Table 2 Frequency of individual MeS components in all subjects and by gender

Discussion

The current study revealed that 3.0% of all study subjects had MeS according to NCEP-III criteria,Citation8 modified by Cook’s criteriaCitation9 with adjustment for fasting glucose to ≥5.6 mM according to American Diabetes Association recommendations.Citation10 Though direct comparison across studies is difficult since the definitions of the syndrome are different, the results of the current study are in agreement with a previous study by Cruz and Goran, which demonstrated that the overall prevalence of MeS in children was 3.0% to 4.0% in the USA.Citation14 The current results are similar to data among Turkish schoolchildren aged 10–19 years (2.3%) according to International Diabetes Foundation (IDF) and NECP-III criteria.Citation15 Using a definition comparable to that projected in NECP-III criteria, a prevalence of 3.6% in children 8–17 years of age was reported by investigators from the Bogalusa Heart Study.Citation16 Using the IDF definition, the prevalence of MeS in Jordanian children 10–15 years old was (1.4%).Citation17 The prevalence of MeS in Caucasian children was reported to be 6.0% to 39.0%,Citation18 while it was 6.7% in Korean children and adolescents.Citation19

Childhood obesity is increasing the likelihood of MeS in children.Citation5 Our results report a high prevalence of MeS (9.5%) and its components among overweight and obese children (). This finding is similar to other studies which demonstrated much higher prevalence rates of MeS in children who were overweight or obese.Citation8,Citation20–Citation22

The reliability of diagnostic criteria for MeS in children has been questioned. It has been found that they require modification to be applicable to children.Citation23 This may account in part for the discrepancies in prevalence between different populations. However, this study, like a number of others, identified the prevalence of various abnormalities (all included within the criteria) separately. In the whole sample studied, the most frequently found abnormality () was hypertriglyceridemia (28.4%) followed by low HDL (19.4%). These findings support those of other studies indicating that the most common abnormality is high triglycerides and low HDL cholesterol in US children.Citation8

This study has strengths and limitations. An important strength is that it provides additional data on Qatari schoolchildren relating to MeS, which was previously lacking. The major limitations are the small sample size and an ongoing debate on the accuracy of diagnosing the MeS in children younger than 10 years old.

In conclusion, our results indicate that though the prevalence of MeS is low overall in Qatari children, overweight and obese children had higher rates of MeS than non-over weight and non-obese children. A large proportion of Qatari schoolchildren had one or two metabolic abnormalities. Further studies are needed, with larger sample sizes, including measurements of hormones and biomarkers known to be involved in pathogenesis and identification of MeS in Qatari school children.

Abbreviations

| BMI | = | body mass index; |

| WC | = | waist circumference; |

| MeS | = | metabolic syndrome; |

| IOTF | = | International Obesity Task Force; |

| ow and ob | = | overweight and obese; |

| non-ow and non-ob | = | non-overweight and non-obese; |

| TC | = | total cholesterol; |

| HDL-C | = | high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; |

| LDL-C | = | low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; |

| TG | = | triglycerides; |

| CVD | = | cardiovascular diseases. |

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grant #CAS05001 from Qatar University, Qatar.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- KaveyREDanielsSRLauerRMAtkinsDLHaymanLLTaubertKAmerican Heart Association guidelines for primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease beginning in childhoodJ Pediatr2003142436837212712052

- JuonalaMViikariJSRonnemaaTAssociations of dyslipidemias from childhood to adulthood with carotid intima-media thickness, elasticity, and brachial flow-mediated dilatation in adulthood: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns StudyArterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol20082851012101718309111

- ReavenGMBanting lecture 1988. Role of insulin resistance in human diseaseDiabetes19883712159516073056758

- WangYLobsteinTWorldwide trends in childhood overweight and obesityInt J Pediatr Obes200611112517902211

- BenerAKamalAAGrowth patterns of Qatari school children and adolescents aged 6–18 yearsJ Health Popul Nutr200523325025816262022

- CrespoPSPrieto PereraJALodeiroFAAzuaraLAMetabolic syndrome in childhoodPublic Health Nutr20071010A1121112517903319

- El-MenyarARizkNAl NabtiADTotal and high molecular weight adiponectin in patients with coronary artery diseaseJ Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown)200910431031519430341

- Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III)JAMA2001285192486249711368702

- CookSWeitzmanMAuingerPNguyenMDietzWHPrevalence of a metabolic syndrome phenotype in adolescents: findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med2003157882182712912790

- GenuthSAlbertiKGBennettPFollow-up report on the diagnosis of diabetes mellitusDiabetes Care200326113160316714578255

- SekiMMatsuoTCarrilhoAJPrevalence of metabolic syndrome and associated risk factors in Brazilian schoolchildrenPublic Health Nutr200912794795218652714

- MaGSJiCYMaJWaist circumference reference values for screening cardiovascular risk factors in Chinese children and adolescentsBiomed Environ Sci2010231213120486432

- ColeTJBellizziMCFlegalKMDietzWHEstablishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international surveyBMJ200032072441240124310797032

- CruzMLGoranMIThe metabolic syndrome in children and adolescentsCurr Diab Rep200441536214764281

- CizmeciogluFMEtilerNHamzaogluOHatunSPrevalence of metabolic syndrome in schoolchildren and adolescents in Turkey: a population-based studyJ Pediatr Endocrinol Metab200922870371419845121

- SrinivasanSRMyersLBerensonGSPredictability of childhood adiposity and insulin for developing insulin resistance syndrome (syndrome X) in young adulthood: the Bogalusa Heart StudyDiabetes200251120420911756342

- KhaderYBatiehaAJaddouHEl-KhateebMAjlouniKMetabolic Syndrome and its individual components among Jordanian children and adolescentsInt J Pediatr Endocrinol20102010316170 [Epub 2010 Dec 9].21197084

- ReinehrTde SousaGToschkeAMAndlerWComparison of metabolic syndrome prevalence using eight different definitions: a critical approachArch Dis Child200792121067107217301109

- LeeYJShinYHKimJKShimJYKangDRLeeHRMetabolic syndrome and its association with white blood cell count in children and adolescents in Korea: the 2005 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination SurveyNutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis201020316517219616924

- WeissRDziuraJBurgertTSObesity and the metabolic syndrome in children and adolescentsN Engl J Med2004350232362237415175438

- DhuperSCohenHWDanielJGumidyalaPAgarwallaVSt VictorRUtility of the modified ATP III defined metabolic syndrome and severe obesity as predictors of insulin resistance in overweight children and adolescents: a cross-sectional studyCardiovasc Diabetol20076417300718

- AgirbasliMCakirSOzmeSCilivGMetabolic syndrome in Turkish children and adolescentsMetabolism20065581002100616839833

- PergherRNMeloMEHalpernAManciniMCIs a diagnosis of metabolic syndrome applicable to children?J Pediatr (Rio J)201086210110820361118