Abstract

Opioid rotation is a common and necessary clinical practice in the management of chronic non-cancer pain to improve therapeutic efficacy with the lowest opioid dose. When dose escalations fail to achieve adequate analgesia or are associated with intolerable side effects, a trial of a new opioid should be considered. Much of the scientific rationale of opioid rotation is based on the wide interindividual variability in sensitivity to opioid analgesics and the novel patient response observed when introducing an opioid-tolerant patient to a new opioid. This article discusses patient indicators for opioid rotation, the conversion process between opioid medications, and additional practical considerations for increasing the effectiveness of opioid therapy during a trial of a new opioid. A Patient vignette that demonstrates a step-wise approach to opioid rotation is also presented.

Introduction

Patients treated with opioid analgesics exhibit broad differences in sensitivity to the analgesic and nonanalgesic effects of these medications.Citation1 Such differences necessitate a highly individualized approach to therapy, with the goal of balancing the therapeutic effects with the side effects. When dose escalations are associated with inadequate analgesia or intolerable side effects, a planned switch from one opioid to another opioid can be considered.Citation2–Citation4 This treatment approach, known as “opioid rotation,” is a common clinical practice intended to improve a patient’s response to treatment.Citation3 Rotating to a new opioid may be necessary at any time after the initiation of therapy. Clinical guidelines recommend opioid rotation for patients with chronic pain who experience a decline in therapeutic efficacy with their current opioid, or for patients who experience inadequate efficacy or intolerable adverse events (AEs) during dose titration.Citation2

The rationale for opioid rotation is based on the wide interindividual variability in sensitivity to opioid analgesics and the novel patient response observed when introducing an opioid-tolerant patient to a new opioid.Citation1,Citation2,Citation4,Citation5 Specifically, patients may respond very differently with respect to analgesic and nonanalgesic effects (eg, adverse effects).Citation5 This variability is the outcome of a complex interaction between drug-related and biological factors.Citation4,Citation5 The differential activities of opioid analgesics are determined, at least in part, by the relative binding affinities to the different opioid receptor classes and subtypes. Opioids used for moderate-to-severe chronic non-cancer pain exert their analgesic effects primarily via mu-opioid receptors, and some data exist for the existence of different subtypes of mu-opioid receptors.Citation6,Citation7 Accordingly, a patient who has displayed marked tolerance to one opioid may display incomplete cross-tolerance to another opioid with a different receptor-binding profile.Citation8,Citation9 This can be manifested clinically as a restoration of analgesic sensitivity upon administration of a different opioid. Individual variation in receptor distribution and sensitivity likely influences the wide range of doses required to obtain adequate analgesia with a given opioid. Theoretically, matching the patient with the proper mu-opioid receptor agonist will allow patients to obtain adequate analgesia with tolerable AEs at the lowest possible dose.

Commonly used opioids for managing moderate-to-severe chronic non-cancer pain include immediate-release (IR) and extended-release (ER) formulations of hydromorphone, morphine sulfate, oxycodone, oxymorphone, and tapentadol, as well as transdermal fentanyl.Citation10–Citation19 Treatment strategies to manage this type of pain include combinations of an ER and IR opioid to provide baseline and supplemental analgesia for breakthrough pain.Citation2 The selection of the opioid should take into account such factors as the patient’s medical status, age, previous exposure to opioid therapy, and access to medication, as well as cost and convenience of administration.Citation2,Citation4 The patient’s likelihood for misuse, abuse, and overdose should also factor in the treatment decision.Citation20 Regardless of which opioid is selected, patients will likely require rotation to a new opioid at some point during treatment to maintain analgesic efficacy. The following discussion provides an approach to implement opioid rotation in patients with chronic non-cancer pain, as well as clinical considerations in the practical management of patients undergoing opioid rotation. In addition, a Patient vignette is presented to illustrate key decision points in opioid rotation.

Approach to opioid rotation

Deciding when to initiate opioid rotation

Attempts at dose escalation often precede opioid rotation, as this is a logical next step for pain patients experiencing inadequate analgesia with their current opioid dose.Citation2,Citation3 However, the clinical utility of administering higher opioid doses is limited by several factors, including an increase of treatment-related AEs (ie, nausea, constipation, somnolence).Citation2,Citation10–Citation17 In addition, no current standard definition for a “high dose” exists, and there is a lack of substantial evidence-based guidance for safe prescribing practices at higher doses.Citation2 Furthermore, although there is no theoretical ceiling dose for pure opioid analgesics,Citation2 with repeated dose escalation and higher daily opioid doses, there is an increased risk for overdose death.Citation21,Citation22 In a study of chronic pain patients, those who received a total daily dose of ≥50 mg/day and ≥100 mg/day morphine equivalent had an approximately 5- and 7-times greater risk of opioid overdose death compared with patients receiving <20 mg/day morphine equivalent, respectively.Citation21

Patient vignette Opioid RotationTable Footnotea

For patients maintained on combination opioid products containing acetaminophen (APAP), careful consideration should also be given to unencumbered dose increases. In response to reports of severe liver injury associated with high doses of APAP, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently limited the amount of APAP in oral combination products to 325 mg/dose, and the total daily dose to 4000 mg/day.Citation25 Additional recommendations call to further limit the total daily dose of APAP to 2600 mg/day.Citation26

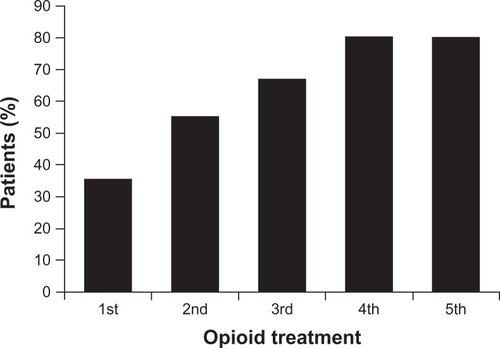

Intolerable AEs or lack of effective analgesia following dose escalation may necessitate rotation to a new opioid ().Citation2,Citation3 It is important to note that this practice is not limited to the introduction of one new opioid, but may be approached as one trial in a sequence of rotations.Citation27 A lack of analgesia or an increase in AEs with the new opioid might indicate the need for a second, or additional, rotation.Citation4 In a retrospective chart review of chronic pain patients prescribed long-acting or ER opioids, the cumulative percentage of patients who achieved an effective, well-tolerated opioid dose increased from 36% after the first rotation to 80% after the fourth rotation ().Citation27

Figure 1 Cumulative percentage of patients achieving an effective opioid dose with opioid rotation.Citation27

Adapted with permission from Quang-Cantagrel et al. Opioid substitution to improve the effectiveness of chronic noncancer pain control: a chart review. Anesth Analg. 2000;90(4):933–937.

Table 1 Major reasons for opioid rotationCitation3

Initiating opioid rotation and patient assessment

The choice of the new opioid should be individualized and based on the patient’s medical status and history, previous exposure to opioids, access to medication, potential risk for abuse, and other psychosocial factors.Citation3 The starting dose of the new opioid is an equally important consideration. Analgesic potency varies among opioids; therefore, equianalgesic dosing tables may be used to calculate the new starting dose ().Citation23,Citation24,Citation28,Citation29 Although these tables are a reasonable starting point for determining an equianalgesic dose of a new opioid, certain limitations should be acknowledged.Citation28 The relative potencies were derived primarily from studies of patients with acute pain, and often with intravenous opioid administration.Citation28 They also do not account for individual patient variability.Citation28 It also has been recognized that equianalgesic doses can underestimate the actual potency of the molecule.Citation3 An additional dose reduction of 25% to 50% below the equianalgesic dose has therefore been recommended (see Patient vignette) to account for underestimated potency and incomplete cross-tolerance among opioids.Citation3 Although a more conservative approach may help safeguard against adverse outcomes in patients particularly sensitive to the new opioid, a 50% additional reduction may not provide adequate analgesia for some patients. For patients undergoing rotation to a new opioid, inadequate analgesia can potentially manifest as breakthrough pain or symptoms of withdrawal (concepts discussed in detail below).Citation3 An IR opioid may therefore be given as a supplemental analgesic.Citation3

Table 2 Original equianalgesic dose tableCitation28

From this author’s clinical experience, converting patients to 66% of the previous total daily opioid dose, or a dose reduction of 33% below the equianalgesic dose, is suggested. In addition, patients can be given an IR opioid for supplemental analgesia, dosed at 33% of the new total daily opioid dose. In line with the principles of responsible opioid prescribing, the individual clinical decision-making process should be based on a comprehensive patient assessment, including past opioid experience and the agreed upon treatment plan.Citation30

Following the initial calculation of the equianalgesic dose, a number of other assessments should be made before administering the new opioid dose. The patient’s current pain intensity, side effect profile, and medical status should be assessed, in addition to other medical and psychosocial factors that may affect the outcome of treatment. In certain cases, an additional 15% to 30% increase or decrease of the daily opioid dose may be applied ().Citation3

Table 3 Expert consensus for a two-step approach to opioid rotationCitation3

Clinical considerations

Opioid selection

As patients managed with chronic opioid therapy likely receive concomitant medications, there is a significant risk of drug–drug interactions.Citation4,Citation31 Opioids that undergo cytochrome P450 (CYP450) isoenzyme metabolism have a greater risk of interaction with concomitant medications metabolized by the same CYP450 pathway.Citation4 Of the ER or controlled-release opioids, hydromorphone, morphine, oxycodone, and tapentadol appear to have little to no interaction with the CYP450 pathway,Citation10,Citation12,Citation13,Citation15,Citation19,Citation32 indicating a lower risk of drug–drug interactions with certain medications.

While it is not possible to predict who is likely to respond to a particular opioid, the patient’s history of opioid exposure may provide important insights. For example, in a patient undergoing a rotation from IR oxycodone to controlled-release oxycodone, there is the potential for a more favorable therapeutic response based on the patient’s previously demonstrated tolerability of this molecule. A similar “molecule matching” approach may also be applicable when rotating a patient from hydrocodone to hydromorphone. Hydrocodone is metabolized, in part, to hydromorphone through the CYP450 (2D6) pathway.Citation33 Patients previously maintained on hydrocodone, and particularly hydrocodone-treated patients who are CYP2D6 rapid metabolizers, theoretically may experience favorable tolerability when converted to hydromorphone.Citation32,Citation34 Likewise, patients previously maintained on oxycodone, which is metabolized, in part, to oxymorphone,Citation35 may be more likely to respond to a rotation to oxymorphone. The validity of this “molecule matching” approach, however, requires confirmation from systematic studies.

Supplemental analgesia to manage breakthrough pain

Although breakthrough pain in patients with chronic non-cancer pain has not been fully characterized, recent studies show a prevalence of 48% to 74% in this patient population, despite having well-controlled baseline persistent pain.Citation36–Citation38 Patients report an average of 1 to 2 episodes per day, with a median time to maximum intensity of 1 to 10 minutes and a median episode duration of 45 minutes to 1 hour.Citation37,Citation38

Patients undergoing opioid rotation may experience breakthrough pain, and this type of pain should undergo a separate assessment from the patient’s baseline persistent pain.Citation2,Citation3 As previously mentioned, an IR opioid may be provided for supplemental analgesia when initiating a new opioid trial (see Patient vignette).Citation3 However, the total daily dose including the primary opioid and the supplemental IR opioid should be considered, given the increased risk of AEs and overdose with high daily doses.Citation21

Rotation to methadone

Additional caution must be taken if rotating a patient’s therapy to methadone.Citation2,Citation3 Methadone is indicated for the treatment of moderate-to-severe pain that is uncontrolled with non-opioid analgesics.Citation2 The 4- to 8-hour duration of analgesic effect makes methadone amenable for use in chronic pain management.Citation39 However, the elimination half-life of the molecule varies widely across patients and may last up to 59 hours.Citation39

In clinical studies, methadone appears to be substantially more potent than previously believed, particularly when rotating from another mu-opioid.Citation40 Specifically, methadone has been reported to reverse mu-agonist opioid tolerance, and deaths have been reported following conversion to methadone in patients receiving other chronic opioid therapy.Citation28,Citation41 The risk of serious, life-threatening AEs, such as respiratory depression and cardiac arrhythmias, can persist beyond the duration of analgesic effects.Citation39 From 1999–2006, there was an approximate 7-fold rise in methadone-related deaths in the US.Citation42 An in-depth knowledge of the variable pharmacokinetics and associated risks of methadone is therefore essential, and current guidelines underline the importance of cautious initiation and dose titration.Citation2

Managing withdrawal

Symptoms of withdrawal can manifest following a dose reduction in chronic pain patients who are tolerant to, and physically dependent on, opioids.Citation43 Patients who undergo rotation may experience withdrawal due to the additional reduction in the equianalgesic dose, necessitating the ability to recognize and manage associated signs and symptoms.Citation3 This can include such autonomic signs as diarrhea, rhinorrhea, and piloerection, as well as central neurologic arousal characterized by sleeplessness, irritability, and psychomotor agitation.Citation43 As the dose is individually titrated to adequate analgesia, however, the symptoms of withdrawal can potentially dissipate.

Policies regulating prescription opioid use

Patients with chronic non-cancer pain require comprehensive treatment, given the common accompaniment of complex comorbidities.Citation2 All health care providers managing patients with opioid analgesics should adhere to good prescribing principles to ensure that the benefits outweigh the risks.Citation2 This includes, but is not limited to, the ability and resources to assess and manage opioid-related AEs and other risks such as misuse, abuse, and diversion.Citation2 Furthermore, compliance with federal and individual state policies governing prescription opioid use is fundamental.Citation44

To ensure that the therapeutic benefit outweighs the risks, the FDA recently announced a classwide Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) for all long-acting and ER opioids.Citation45 Under this program, prescribers will be required to undergo training on appropriate and safe prescribing practices.Citation45 Since opioid rotation requires the knowledge to safely prescribe a range of opioid formulations, education provided through this REMS should act as a complementary measure. Patients will also receive materials and undergo counseling on safe use.Citation45 Importantly, this information will include points on proper opioid disposal.Citation45 As rotation from one opioid to another may leave unused doses, patients should be advised to flush their unused medication to avoid the risk of accidental exposure.Citation46

Although not currently implemented, future legislation may require a prescriber to undergo training as part of US Drug Enforcement Administration registration.Citation47 Preemptive and active participation in classwide REMS for ER opioids is therefore encouraged.

Conclusion

Current scientific knowledge limits the ability to predict which patient will respond optimally to which opioid analgesic. Opioid rotation is therefore a necessary practice in the management of chronic non-cancer pain to achieve therapeutic efficacy with the lowest possible dose. Even patients who respond favorably to initial opioid therapy may require rotation to a new opioid over time to maintain adequate analgesia. Importantly, this practice also minimizes the risks of AEs and overdose associated with frequent dose escalations and higher daily opioid doses. Clinical judgment based on the individual patient should be used when determining the new opioid for rotation, and careful attention should be taken to individualize the starting dose. Guided by state policies and responsible prescribing practices, opioid rotation can be safely and effectively implemented in clinical practice.

Acknowledgements

Technical editorial and writing assistance for the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Meg Church, Synchrony Medical, LLC, West Chester, PA. Funding for this support was provided by Mallinckrodt Inc, a Covidien company, Hazelwood, MO.

Disclosure

Dr Nalamachu discloses that he was a principal investigator for an extended-release hydromorphone trial conducted by Neuromed. He has also received research grants from Mallinckrodt Inc, a Covidien company, and is a member of their Speakers Bureau.

References

- GalerBSCoyleNPasternakGWPortenoyRKIndividual variability in the response to different opioids: report of five casesPain199249187911375728

- ChouRFanciulloGJFinePGOpioid treatment guidelines: clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer painJ Pain200910211313019187889

- FinePGPortenoyRKAd Hoc Expert Panel on Evidence Review and Guidelines for Opioid Rotation. Establishing “best practices” for opioid rotation: conclusions of an expert panelJ Pain Symptom Manage200938341842519735902

- SlatkinNEOpioid switching and rotation in primary care: implementation and clinical utilityCurr Med Res Opin20092592133215019601703

- MercadanteSOpioid rotation for cancer pain: rationale and clinical aspectsCancer19998691856186610547561

- PanLXuJYuRXuMMPanYXPasternakGWIdentification and characterization of six new alternatively spliced variants of the human mu opioid receptor gene, OprmNeuroscience2005133120922015893644

- PasternakGWIncomplete cross tolerance and multiple mu opioid peptide receptorsTrends Pharmacol Sci2001222677011166849

- EckhardtKLiSAmmonSSchänzleGMikusGEichelbaumMSame incidence of adverse drug events after codeine administration irrespective of the genetically determined differences in morphine formationPain1998761–227339696456

- RussellRDChangKJAlternated delta and mu receptor activation: a stratagem for limiting opioid tolerancePain19893633813892540475

- Exalgo [package insert]Hazelwood, MOMallinckrodt Inc, a Covidien company2010

- Embeda [package insert]Bristol, TNKing Pharmaceuticals2009

- Oxycontin [package insert]Stamford, CTPurdue Pharma LP2010

- Avinza [package insert]Bristol, TNKing Pharmaceuticals Inc2008

- OpanaER [package insert]Chadds Ford, PAEndo Pharmaceuticals Inc2008

- Kadian [package insert]Morristown, NJActavis Elizabeth LLC2010

- MS Contin [package insert]Stamford, CTPurdue Pharma LP2009

- Oramorph SR [package insert]Newport, KYXanodyne Pharmaceuticals Inc2006

- Duragesic [package insert]Raritan, NJPriCara, Division of Ortho-McNeil-Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc2006

- NucyntaER[package insert]Titusville, NJJanssen Pharmaceuticals Inc2011

- GourlayDLHeitHAAlmahreziAUniversal precautions in pain medicine: a rational approach to the treatment of chronic painPain Med20056210711215773874

- BohnertASValensteinMBairMJAssociation between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deathsJAMA2011305131315132121467284

- DunnKMSaundersKWRutterCMOpioid prescriptions for chronic pain and overdose: a cohort studyAnn Intern Med20101522859220083827

- HaleMKhanAKutchMLiSOnce-daily OROS hydromorphone ER compared with placebo in opioid-tolerant patients with chronic low back painCurr Med Res Opin20102661505151820429852

- PalangioMNorthfeltDWPortenoyRKDose conversion and titration with a novel, once-daily, OROS osmotic technology, extended-release hydromorphone formulation in the treatment of chronic malignant or nonmalignant painJ Pain Symptom Manage200223535536812007754

- US Food and Drug AdministrationQuestions and answers about oral prescription acetaminophen products to be limited to 325 mg per dosage unit Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/ucm239871.htm. Accessed October 7, 2011.

- US Food and Drug AdministrationAcetaminophen overdose and liver injury – background and options for reducing injury Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/DrugSafetyandRiskManagementAdvisoryCommittee/UCM164897.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2011.

- Quang-CantagrelNDWallaceMSMagnusonSKOpioid substitution to improve the effectiveness of chronic noncancer pain control: a chart reviewAnesth Analg200090493393710735802

- KnotkovaHFinePGPortenoyRKOpioid rotation: the science and the limitations of the equianalgesic dose tableJ Pain Symptom Manage200938342643919735903

- MahlerDLForrestWHJrRelative analgesic potencies of morphine and hydromorphone in postoperative painAnesthesiology197542560260748347

- SmithHFinePPassikSOpioid Risk Management: Tools and TipsNew YorkOxford University Press Inc2009

- Parsells KellyJCookSFKaufmanDWAndersonTRosenbergLMitchellAAPrevalence and characteristics of opioid use in the US adult populationPain2008138350751318342447

- SmithHSOpioid metabolismMayo Clin Proc200984761362419567715

- ConeEJDarwinWDGorodetzkyCWTanTComparative metabolism of hydrocodone in man, rat, guinea pig, rabbit, and dogDrug Metab Dispos19786448849328931

- OttonSVSchadelMCheungSWKaplanHLBustoUESellersEMCYP2D6 phenotype determines the metabolic conversion of hydrocodone to hydromorphoneClin Pharmacol Ther19935454634727693389

- LalovicBPhillipsBRislerLLHowaldWShenDDQuantitative contribution of CYP2D6 and CYP3A to oxycodone metabolism in human liver and intestinal microsomesDrug Metab Dispos200432444745415039299

- ManchikantiLSinghVCarawayDLBenyaminRMBreakthrough pain in chronic non-cancer pain: fact, fiction, or abusePain Physician2011142E103E11721412376

- PortenoyRKBennettDSRauckRPrevalence and characteristics of breakthrough pain in opioid-treated patients with chronic noncancer painJ Pain20067858359116885015

- PortenoyRKBrunsDShoemakerBShoemakerSABreakthrough pain in community-dwelling patients with cancer pain and noncancer pain, part 1: prevalence and characteristicsJ Opioid Manag2010629710820481174

- US Food and Drug AdministrationInformation for healthcare professionals: methadone hydrochlorideRockville, MDUS Food and Drug Administration2006

- BrueraEPereiraJWatanabeSBelzileMKuehnNHansonJOpioid rotation in patients with cancer pain. A retrospective comparison of dose ratios between methadone, hydromorphone, and morphineCancer19967848528578756381

- DavisAMInturrisiCEd-Methadone blocks morphine tolerance and N-methyl-D-aspartate-induced hyperalgesiaJ Pharmacol Exp Ther199928921048105310215686

- WarnerMChenLHMakucDMIncrease in fatal poisonings involving opioid analgesics in the United States, 1999–2006NCHS Data Brief.2009221819796521

- SavageSRJoransonDECovingtonECSchnollSHHeitHAGilsonAMDefinitions related to the medical use of opioids: evolution towards universal agreementJ Pain Symptom Manage200326165566712850648

- GilsonAMJoransonDEMaurerMAImproving state pain policies: recent progress and continuing opportunitiesCA Cancer J Clin200757634135317989129

- US Food and Drug AdministrationPost-approval REMS notification letter Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/UCM251595.pdf. Accessed July 29, 2011.

- US Food and Drug AdministrationDisposal of unused medicines: what you should know Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/BuyingUsingMedicineSafely/EnsuringSafeUseofMedicine/SafeDisposalofMedicines/ucm186187.htm. Accessed September 12, 2011.

- US Food and Drug AdministrationQuestions and answers: FDA requires a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) for long-acting and extended-release opioids Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/ucm251752.htm. Accessed July 29, 2011.