Abstract

A 25-year-old man had complained of sudden fever spikes for two years and his blood tests were within the normal range. In 1993, a surgical biopsy of swollen left inguinal lymph nodes was negative for malignancy, but showed reactive lymphadenitis and widespread sinus histiocytosis. A concomitant needle biopsy of the periaortic lymph nodes and a bone marrow aspirate were also negative. In 1994, after an emergency hospital admission because of a sport-related thoracic trauma, a right inguinal lymph node biopsy demonstrated Hodgkin’s lymphoma Stage IVB (scleronodular mixed cell subtype). Although it was improved by chemotherapy, the disease suddenly relapsed, and a further lymph node biopsy was performed in 1998 confirming the same diagnosis. Despite further treatment, the patient died of septic shock in 2004, at the age of 38 years. Retrospective analysis of the various specimens showed intracellular heavy metal nanoparticles within lymph node, bone marrow, and liver samples by field emission gun environmental scanning electron microscopy and energy dispersive spectroscopy. Heavy metals from environmental pollution may accumulate in sites far from the entry route and, in genetically conditioned individuals with tissue specificity, may act as cofactors for chronic inflammation or even malignant transformation. The present anecdotal report highlights the need for further pathologic ultrastructural investigations using serial samples and the possible role of intracellular nanoparticles in human disease.

Introduction

Environmental pollution and occupational exposure to heavy metals are considered possible cofactors in the occurrence of both chronic and malignant diseases. The bulk of epidemiologic and in vitro studies, as well as studies in experimental animals, support the hypothesis that a cause and effect relationship exists between chronic irritation (oxidative stress) by heavy metals and carcinogenesis. Unfortunately, there is a complete lack of relevant human studies, in particular concerning pathologic examination of serial samples collected at various time intervals and showing host–particle interaction at the ultrastructural level.

Hodgkin’s disease is a malignant systemic lymphoma which affects a large number of young people. Its occurrence has been occasionally related to viral pathogenesis because of the prevalence of Epstein–Barr virus infection in different types and locations of lymphoma.Citation1–Citation4 Sometimes the clinical history starts with remitting episodes of fever followed by lymph node swelling, biopsy and pathologic examinations, which detects typical malignant degeneration, with Reed–Sternberg cells spreading into the infiltrated lymphoreticular network. The progression from nonspecific lymphadenitis to lymphoma is seldom histologically depicted because of the speed of transformation.

Our case report describes a 25-year-old man who, at the beginning of his disease, had lymph node enlargement for at least one year and underwent repeated biopsy of the nodes and bone marrow until a diagnosis of Hodgkin’s lymphoma was finally made.

We have investigated the possibility of a link between exposure to environmental particulate matter and development of lymphomaCitation5,Citation6 using a new investigational tool, ie, field emission gun-environmental scanning electron microscopy (FEG-ESEM) coupled with energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) to determine the chemical composition of the particles identified. We have investigated nanoparticle storage in lymph nodes and involved tissues retrospectively. This research has highlighted the presence of heavy metal nanoparticles in cells and opens the debate on their pathogenetic role in the onset of Hodgkin’s disease.

Case report

This investigation has been performed in a young European male (1967–2004). He was a racing car driver who was regularly exposed to toxic air pollution. In 1985, the patient underwent appendectomy for acute appendicitis with moderate leukocytosis (white blood cells).Citation4,Citation10 Two years later, he suffered from head and spine trauma, followed by a motorbike accident the following year. The latter led to a fracture of the left tibia which was surgically treated with a titanium pin.

In May 1993, the patient was hospitalized due to an unremitting fever (37.5°C) which lasted for one month. A laboratory analysis was performed, and the results were negative for cytomegalovirus, pathogenic fecal bacteria, HIC, human immunodeficiency virus, Epstein–Barr virus, Brucella, Shigella, and Salmonella typhimurium, but a toxoplasmosis test was positive, and a computed tomography scan showed enlarged paraortic lymph nodes and an enlarged left inguinal lymph node. A needle biopsy of the periaortic lymph nodes and a bone marrow biopsy showed an inflammatory mixed cell response.

In July 1993, the surgical biopsy of a left inguinal node led to the diagnosis of reactive lymphadenitis with widespread immature sinus histiocytosis, but without paracortical tissue enlargement and a normal immunophenotype. In February 1994, the tibial pin was removed and, following the operation, the fever disappeared. Five months later, the radiogallium lymph node scintigraphy suggested a possible diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Two months later, the patient suffered a sports-related thoracic trauma which resulted in an emergency hospital admission. A plain chest X-ray showed bilateral hilar polycyclic lymphadenopathy with right upper and middle lobe infiltration, raising the suspicion of lymphoma. A bone marrow biopsy showed a pattern related to chronic infections and atypical lymphocytes (less than 5%), whereas a right inguinal lymph node biopsy showed weakly positive Leu M1 Reed–Sternberg cells. Lymphatic cells were UCHL1- and CD3-positive (T lymphocytes), and a minority were L26-positive (B lymphocytes). Finally, Hodgkin’s lymphoma Stage IVB (scleronodular mixed cell subtype) was diagnosed. The patient underwent radiochemotherapy with partial volumetric regression of the right thoracic paraortic lymph nodes.

In 1997, further lesions were found in the spleen. The total body positron emission tomography revealed the involvement of the liver at the VII segment level, confirmed by an ultrasound scan showing additional lesions at the V, VII, and VIII segments. Histologic analysis of the ultrasound-guided liver biopsy showed Reed–Sternberg cell infiltration.

In June 1998, a computed tomography (CT) scan showed relapse of the thoracic lesions. The patient was treated with rituximab. Despite treatment, the disease progressed with bone involvement. In late November 1998, a further lymph node biopsy confirmed the presence of Hodgkin’s disease (scleronodular mixed cell subtype). The patient died of septic shock in May 2004.

Materials and methods

Tissue samples analyzed included a left inguinal lymph node in 1993, a right lymph node in the groin area in 1994, a bone marrow biopsy in 1994, and another lymph node in 1998. Biopsy samples of benign (on the right) and malignant (on the left) lymph nodes and bone marrow were fixed in 10% formalin, dehydrated in ascending concentration alcohols, and embedded in paraffin. A Leica microtome (RM 2125RT; Lecia Nussloch, Germany) was used to cut biopsy sections 10 μ in thickness. The sections were deposited on an acetate sheet and deparaffined with xylol. After that, with a few drops of xylol and 98% alcohol, they were mounted on an aluminum stub and inserted inside the chamber of a FEG-ESEM Quanta (FEI Company, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) coupled with an EDS (EDAX, Mahwah, NJ). The use of the FEG-ESEM was recommended because it does not need any further process to make the sample electron-conductive (gold or carbon coating of the biologic sections). The EDS microanalysis system was used to identify the elemental composition of inorganic materials (foreign bodies) identified in the biopsy samples. The working conditions of the FEG-ESEM were low-vacuum, from 20 to 30 kV, in secondary and backscattered electron modality, with spots 3–5. For every sample, a list of the particles found in the sample was given, along with their size, morphology, and chemical composition.

Discussion

Microsized and nanosized foreign bodies have been identified in all the samples analyzed. shows a summary of the most representative particles identified in the lymph node and bone marrow biopsies, taken at different stages of the disease, described according to morphology, size and chemical composition. Particle accumulation is not uniform, and this might have been due to asymmetry of the lymphatic circulation. The debris consists of heavy metals, including stainless steel and chromium compounds. These are not biocompatible and, over time, release highly toxic ions, including iron, chromium, and nickel. Our investigation shows an increased amount of metallic foreign bodies, with progression of the disease and progressive amounts of submicroscopic calcium storage.Citation7

Table 1 Type, chemical composition, and size of particles identified in lymph node samplesTable Footnote*

Chromium compounds produce a variety of types of DNA damage, including single-strand breaks, alkali-labile sites, and DNA protein crosslinks. These compounds bind isolated DNA and proteins, readily enter cells via anion channels, but do not cross cell membranes. Chromium inhibits the transcriptional activity of nuclear factor-kappa B by decreasing the interaction of p65 with cAMP-responsive element-binding protein.Citation8,Citation9

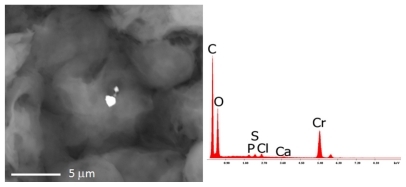

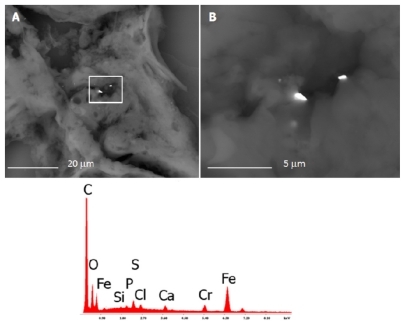

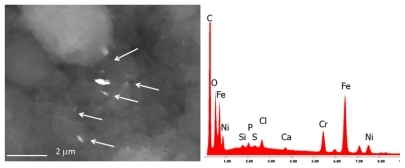

shows submicronic particles (white spots) in the left lymph node biopsy sample. These particles appear whiter than the biologic substrate because they are atomically denser. The biologic tissue is only composed of carbon, oxygen, phosphorus, sulphur, and chlorine, whereas the particles contain chromium with traces of calcium. Chromium is chemically toxic in biologic tissue and can also release chromium ions which worsen the toxicity.Citation10–Citation13 Raised concentrations of circulating metal degradation products, derived from orthopedic implants, may have deleterious biologic effects over time. Accurate monitoring of metal concentrations in serum and urine, after total hip replacement, can provide insights into the mechanisms of metal release. Corrosion significantly raises metal levels, including nickel and chromium in serum and urine, when compared with patients with no radiologic evidence of corrosion and volunteers without metallic implants (P < 0.001).Citation14–Citation18 Samples of the progression of the disease are shown in and . A progressively increasing number of microsized and nanosized metallic particles have been found.

Figure 1 The microphotograph shows two submicronic particles (the white spots) embedded in the left lymph-node biopsy sample. The EDS spectrum shows the chemical composition: carbon, oxygen, chromium, phosphorus, sulfur, and chlorine.

Figure 2 The microphotograph shows the analyses carried out on the right lymph-node with the EDS spectrum on the chemical composition of the debris. Nanoparticles of iron, chromium, and silicon are identified.

Figure 3 The bone marrow sample shows the presence of many nanoparticles (range 150 nm–5 μm) composed of iron, chromium, and nickel, namely debris of stainless steel.

Our case report describes for the first time a pathophysiologic and ultrastructural five-year follow-up of lymph nodes obtained from the same patient. It shows the progressive storage of heavy metal nanoparticles in lymphatic tissue, which was in parallel with progression of a cancerous process from early chronic inflammation to Hodgkin’s disease. This is a unique case report relating to one-year progression from lymphadenitis to lymphoma in the inguinal region of a patient, where the increasing presence of foreign inorganic microsized and nanosized bodies has been demonstrated. Although the patient underwent appendectomy and tested positive for toxoplasmosis which may be associated with malignancies, this relationship was unlikely in our patient. His appendectomy dated back to childhood, and toxoplasmosis did not lead to infection with encephalic damage. Furthermore, we found no evidence of immunosuppression during the lymphoma incubation period.

Heavy metals, such as iron, chromium and nickel, are the main constituents of foreign bodies found in cells.Citation9,Citation11,Citation19–Citation21 Occupational or incidental heavy exposure to many chemicals, including benzene, pesticides, ethylene oxide and metals (mercury, cadmium, chrome, cobalt, lead, aluminum) is very dangerous for the hematopoietic system. Mercury and chromium cause immunosuppression and evoke autoimmune reactions.Citation10–Citation12,Citation22–Citation25

An epidemiologic study assessing cancer risk in a small population exposed to excessive amounts of chromiumCitation9 reported two cases of Hodgkin’s disease after protracted exposure and a long latency period. The calculated and observed risk in this study is 65–92-fold higher than in nonexposed populations. Clinicians should be aware of the potential association between hexavalent chromium exposure and Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

The particles have been identified as foreign bodies arising from environmental pollution. Their identification in anatomic areas, far from the putative route of entry, raises the issues of whether the mechanism of entrance, internal distribution (streaming), and uptake (selective or not) in the human body involves a potential respiratory or digestive source, and the potential pathogenic mechanism by which nonbiocompatible nanosized foreign bodies cause a chronic inflammatory reaction in lymphatic tissue progressing to Hodgkin’s lymphoma.Citation11,Citation19,Citation21,Citation26

The possibility of environmental pollutants spreading inside the body after inhalation has been shown by Péry et alCitation27 in a study involving five volunteers after inhalation of technetium-radiolabeled 100 nm carbon particles. They demonstrated that these radiolabeled nanoparticles overwhelm the lung barrier within 60 seconds and are stored in the liver within 60 minutes. After this time, the radioactive signal decreases, but there can be a wider dispersion through the blood circulation. Evidence of submicronic particles spreading in different organs or regions, including sperm and brain tissue, has been shown previously. The transport of nanosized particles, due to their consistently small size, may be mediated by blood cells or other blood or lymph components. The toxicologic pathway can be identified in the absence of biocompatibility. In particular, metal nanoparticles may produce toxic ions locally by delayed corrosion mechanisms.Citation14–Citation18 Trapping of these nanoparticles within lymphatic cells, with mutagenic and carcinogenic potential via an inflammatory reaction, could elicit a cytokine cascade and lymph node engulfment, with further critical concentration of nanomaterials up to the level inducing carcinogenic mutations.

With regard to the present case report, it would have been helpful if the patient had been followed up during the five years preceding 1993, ie, when the progression from chronic inflammation to cancerous disease actually occurred. However, it is important to bear in mind the difference between experimental research using animal models and that using human subjects, whereby the latter must conform to more stringent ethical rules. In the absence of more robust data on humans demonstrating a clear-cut cause and effect relationship between chronic exposure to heavy metals and malignancies (not only on the basis of epidemiologic correlation studies, but on the basis of pathologic evidence, such as in the present report), we believe that the present case report could be useful to the scientific community. However, caution is recommended when interpreting the results of a single case report, as well as those of small studies such as that one by Bick et al,Citation11 in which small numbers could be responsible for bias in risk calculation. In addition, as our extended studies have already suggested,Citation5,Citation6,Citation28–Citation33 environmental pollutants are usually present in such a small concentration in the atmosphere that they are unlikely to be solely responsible for the occurrence of malignant disease in the absence of a congenital or inherited predisposition in the host. On the contrary, in the presence of frail predisposed subjects, even small amounts of pollutants could be cofactors for the occurrence of chronic or even malignant diseases.Citation1

Our anecdotal report highlights the need for ultrastructural investigation in a larger sample of patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma. It suggests the possibility that, at least in some subtypes, or in a proportion of subjects with Hodgkin’s disease, the progression from chronic lymphadenitis to overt malignancy can be facilitated or codetermined in addition to genetic or congenital factors. Moreover, it is likely to happen by chronic exposure or accumulation of heavy metal nanoparticles within lymph nodes, which could determine additional carcinogenetic mutations.

Acknowledgments

The authors are deeply indebted to Lavinia Nitu and Roberta Salvatori for their technical support and the Associazione Ricerca è Vita Onlus of Modena for the support in this investigation. FC has been suggested by the Prolife Project funded by the City of Milan. This article has not been supported by grants.

Disclosure

The authors certify that there is no conflict of interest with any financial organization regarding the material discussed in the manuscript.

References

- HjalgrimHRostgaardKJohnsonPCHLA-A alleles and infectious mononucleosis suggest a critical role for cytotoxic T-cell response in EBV-related Hodgkin lymphomaProc Natl Acad Sci U S A2010107146400640520308568

- KüppersRMolecular biology of Hodgkin lymphomaHematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program200949149620008234

- SchmitzRStanelleJHansmannMLKüppersRPathogenesis of classical and lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphomaAnnu Rev Pathol2009415117419400691

- MathasSDörkenBJanzMThe molecular pathogenesis of classical Hodgkin lymphomaDtsch Med Wochenschr2009134391944194819760557

- CettaFDhamoAMoltoniLBolzacchiniEAdverse health effects from combustion-derived nanoparticles: The relative role of intrinsic particle toxicity and host responseEnviron Health Perspect20091175A19019478977

- CettaFDhamoAMalagninoGGaleazziMLinking environmental particulate matter with genetic alterationsEnviron Health Perspect20091178A34019672380

- AnghileriLJMayayoEDomingoJLThouvenotPCellular calcium homeostasis changes in lymphoma-induction by ATP iron complexOncol Rep200291616411748456

- WoŸniakKMolecular effects of chromium compound activityPostepy Hig Med Dosw19965043833949019747

- ShumillaJABroderickRJWangYBarchowskyAChromium(VI) inhibits the transcriptional activity of nuclear factor-kappaB by decreasing the interaction of p65 with cAMP-responsive element-binding protein-binding proteinJ Biol Chem199927451362073621210593907

- DaiHLiuJMalkasLHCatalanoJAlagharuSHickeyRJChromium reduces the in vitro activity and fidelity of DNA replication mediated by the human cell DNA synthesomeToxicol Appl Pharmacol2009236215416519371627

- BickRLGirardiTVLackWJCostaMTitelbaumDHodgkin’s disease in association with hexavalent chromium exposureInt J Hematol19966434257262

- NickensKPPatiernoSRCeryakSChromium genotoxicity: A double-edged swordChem Biol Interact2010188227628820430016

- O’BrienTJCeryakSPatiernoSRComplexities of chromium carcinogenesis: Role of cellular response, repair and recovery mechanismsMutat Res200353312336

- Del RioJBeguiristainJDuartJMetal levels in corrosion of spinal implantsJ Eur Spine J200716710551061

- ClarkeMTLeePTAroraAVillarRNLevels of metal ions after small- and large-diameter metal-on-metal hip arthroplastyJ Bone Joint Surg Br200385691391712931818

- JacobsJJSkiporAKPattersonLMMetal release in patients who have had a primary total hip arthroplasty. A prospective, controlled, longitudinal studyJ Bone Joint Surg Am19988010144714589801213

- JacobsJJGilbertJLUrbanRMCorrosion of metal orthopaedic implantsJ Bone Joint Surg Am19988022682829486734

- KeeganGMLearmonthIDCaseCPA systematic comparison of the actual, potential, and theoretical health effects of cobalt and chromium exposures from industry and surgical implantsCrit Rev Toxicol200838864567418720105

- CunzhiHJiexianJXianwenZJingangGSulingHClassification and prognostic value of serum copper/zinc ratio in Hodgkin’s diseaseBiol Trace Elem Res200183213313811762530

- McCarrollNKeshavaNChenJAkermanGKligermanARindeEAn evaluation of the mode of action framework for mutagenic carcinogens case study II: Chromium (VI)Environ Mol Mutagen20105128911119708067

- KrishnaSGRanadeSSNairMIron, zinc, copper, manganese and magnesium in malignant lymphomasSci Total Environ19854232372434001919

- ElbekaiRHEl-KadiAOModulation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor-regulated gene expression by arsenite, cadmium, and chromiumToxicology2004202324926915337587

- ZhangMChenZChenQZouHLouJHeJInvestigating DNA damage in tannery workers occupationally exposed to trivalent chromium using comet assayMutat Res20086541455118541454

- BeyersmannDHartwigACarcinogenic metal compounds: Recent insight into molecular and cellular mechanismsArch Toxicol200882849351218496671

- GattiAMontanariSNanopathology: The Impact of NanoparticlesSingaporePan Stanford Publishing2008

- BakareAAPandeyAKBajpayeeMDNA damage induced in human peripheral blood lymphocytes by industrial solid waste and municipal sludge leachatesEnviron Mol Mutagen2007481303717163505

- PéryARBrochotCHoetPHNemmarABoisFYDevelopment of a physiologically based kinetic model for 99 m-technetium-labelled carbon nanoparticles inhaled by humansInhal Toxicol200921131099110719814607

- CettaFBenoniSZangariRGuercioVMontiMEpidemiology, public health, and false-positive results: The role of the clinicians and pathologistsEnviron Health Perspect2010118a24020515720

- EdwardsTMMyersJPEnvironmental exposures and gene regulation in disease etiologyEnviron Health Perspect200711591264127017805414

- DollREpidemiological evidence of the effects of behaviour and the environment on the risk of cancerRecent Results Cancer Res199815432110026990

- PyszelAWróbelTSzubaAAndrzejakREffect of metals, benzene, pesticides and ethylene oxide on the haematopoietic systemMedycyna Pracy200556324925516218139

- HartJEGarshickEDockeryDWSmithTJRyanLLadenFLong-term ambient multi-pollutant exposures and mortalityAm J Respir Crit Care Med2010723 [Epub ahead of print]

- GaudryJSkieharKPromoting environmentally responsible health careCan Nurse20071031222617269580