Abstract

The presence of eosinophilic inflammation is a characteristic feature of chronic and acute inflammation in asthma. An estimated 5%–10% of the 300 million people worldwide who suffer from asthma have a severe form. Patients with eosinophilic airway inflammation represent approximately 40%–60% of this severe asthmatic population. This form of asthma is often uncontrolled, marked by refractoriness to standard therapy, and shows persistent airway eosinophilia despite glucocorticoid therapy. This paper reviews personalized novel therapies, more specifically benralizumab, a humanized anti-IL-5Rα antibody, while also being the first to provide an algorithm for potential candidates who may benefit from anti-IL-5Rα therapy.

Introduction

In 2007, the incremental cost due to asthma was $56 billion in the United States,Citation1 and worldwide the costs are much higher. Of the estimated 25–30 million asthmatics in the United States, the majority of the annual costs incurred are from the 5%–10% of patients with severe asthma. With the advent of novel biological therapies that have been most recently approved for severe asthma, health economists and society will look closely on whether these medications decrease or increase total costs. A high prevalence of severe asthmatics are seen in African-Americans, Puerto Rican Americans, Cuban Americans, women, and those of age ≥65 years. It is imperative that we comprehend the global impact of these new treatments, especially in these populations.

Current modalities of treatments have demonstrated that asthmatics will have variations in response and outcomes. The majority of asthmatics respond well to a written asthma action plan of pharmacotherapy with inhaled corticosteroids often combined with long- or short-acting β-agonist bronchodilators (LABA or SABA) and leukotriene antagonists (LTRAs). Despite aggressive therapy, it is unclear why 5%–10% of asthmatics with severe asthma do not respond to their prescribed regimen. An explanation to this conundrum may be attributed to gaps in medical knowledge and deficiencies in experience on the identification of severe asthma. Other potential barriers are clinical restraints in coordination, integration, and resources for advanced treatments such as omalizumab, bronchial thermoplasty (BT), and now a novel biologic, such as benralizumab. Several key questions need to be addressed before embracing novel biologics as a potential mainstay treatment for asthma, “Should patients be tried on omalizumab before anti-IL5 therapies?” and “If patients have an incomplete response to omalizumab, should anti-IL5 treatment be added?” In this paper, we will review the opportunities for treating patients with severe, persistent asthma with novel biological agents, such as benralizumab, and present a framework for understanding such patients.

Better phenotyping

Most adults with severe asthma develop their disease in childhood. Corticosteroid-resistant asthmatics represent a critical subset of severe asthmatics. Although uncommon, it is estimated that corticosteroid-resistant asthma accounts for 0.01%–0.1% of all patients with asthma;Citation2 however, a retrospective review at National Jewish Health demonstrated that of their severe asthmatics, 25% were found to be corticosteroid resistant.Citation3 More recently, Woodruff et alCitation4 outlined a “Th-2 high and Th-2 low group”. The T-helper type 2 (Th-2) lymphocytes are defined by the cytokines, namely, interleukins (ILs) IL-4, -5, and -13, all of which are important in the development and persistence of eosinophilic, allergic airway inflammation. In this 8-week study, Th-2 high subjects had an increase of 300 mL in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) on an average with inhaled fluticasone, and this was significantly greater than that in either the Th-2 low or the placebo (control) groups. This study was one of the first to show clear responses to therapy tailored to the specific phenotype of severe asthmatics.

To date, there is no laboratory test or biomarker that exists to readily distinguish severe asthma from less-severe asthma phenotypes and has the ability to predict a favorable response to treatment. The best predictor of adverse outcomes and excessive use of asthma control medications appears to be the baseline FEV1.Citation5,Citation6 Fraction of exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) is increased in asthmatic patients and, although NO concentrations may vary greatly (normal <25 ppb in adults), increases and decreases in NO levels correlates well with improvement and deterioration in asthma symptoms, respectively.Citation7 In addition, NO does not appear to be increased in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), making the differentiation between these conditions easier. Despite FeNO and sputum eosinophils, it is still difficult to differentiate in severe asthmatics between those who respond to treatment versus those who will not.Citation8

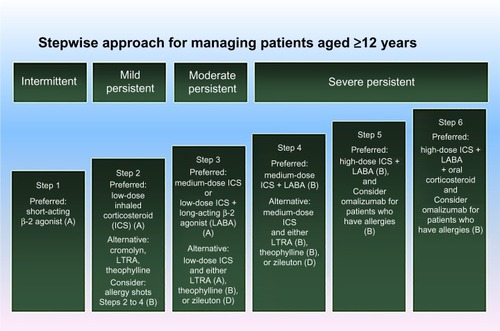

Evaluation of potential candidates

When considering advanced asthma therapies such as injections (omalizumab and benralizumab) and BT, our approach to the evaluation of a severe asthma patient would include first ascertaining that the diagnosis of severe asthma is correct, that is, we exclude other diagnoses and identify confounding comorbidities, even if this is the third or fourth evaluation (). After reevaluation of the diagnosis of asthma, we attempt to understand the asthma phenotype by age stratification and lung function.Citation5 Phenotyping also includes understanding of serum total immunoglobulin E (IgE) and radioallergosorbent test panel to detect atopy and fungal sensitivities, FeNO, and peripheral blood eosinophil numbers.Citation9 In addition, we would consider a chest computed tomography for bronchiectasis and other structural lung changes if the diffusion capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide is abnormal. Often, a chest radiograph will suffice. Lastly, it is important to consider fiber optic bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage and endobronchial and transbronchial biopsies. For example, if we find a positive serology for Aspergillus spp. or other fungus in the right clinical situation, we consider treatment for 8 months with itraconazole 200 µg twice daily.Citation9 If we want to truly assess the steroid responsiveness, we treat the patient with 12 days of prednisone, often in the late afternoon rather than the morning, eg, 40 mg ×3 days, 30 mg ×3 days, 20 mg ×3 days, 10 mg ×3 days, and ask him/her to return to the clinic to determine if his/her asthma is refractory to corticosteroids. A favorable response to oral corticosteroids, for example, improvement in symptoms, FeNO, and spirometry, would force us to consider leaving the patient on low-dose prednisone 1–3 mg daily in addition to high dose, inhaled steroids and LABA, as in Step 6 of the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) table (). At this point, consistent with the NAEPP guidelines, we consider additional adjunct therapies, including zileuton SR for 2–6 weeks (Step 3), which inhibits leukotriene B4 synthesis and modulates neutrophil infiltration. Also, we would consider theophylline, which is a phosphodiesterase-4-inhibitor (Step 3), but the latter is not US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for asthma despite evidence of a mild bronchodilator effect and reduction in sputum eosinophils and neutrophils.Citation10 We tend to use montelukast only if the patient derives clear clinical benefit (Step 3). Outside the NAEPP guidelines, but consistent with more recent evidence, we strongly consider adding tiotropium and measure FEV1 in a scheduled follow-up visit 2 weeks later at the minimum.Citation11 Tiotropium and LABA have an additive effect on bronchodilating the airways. At Step 5 of the guidelines, we would treat with omalizumab if IgE is elevated and radioallergosorbent test is positive for a perennial aeroallergen. We monitor such patients in clinic for anaphylaxis for 2 hours the first 3 injections (captures 75% of anaphylactic reactions) and would discontinue if there is no clinical benefit. Along with omalizumab at steps 5 and 6, we consider BT if the patient fails to improve, or we go to BT immediately if the patient elects to go with BT or declines omalizumab. This is the stage of evaluation and disease where we would place benralizumab and other anti-IL-5 injection therapies, particularly in the patients with severe asthma with mild peripheral eosinophil count elevations (>300 cells/µL).

Figure 1 NAEPP stepwise approach to managing asthma with grades of recommendations.Citation72

Abbreviations: ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting β-agonist bronchodilators; LTRA, leukotriene antagonist; NAEPP, National Asthma Education and Prevention Program.

Rationale for novel biologics

There has been recognition of various asthma phenotypes and endotypes, as well as an increase in understanding of asthma pathogenesis, which allow for a targeted, personalized approach to refractory asthma.Citation12 Omalizumab is one of the soon-to-be many personalized approaches that will be in the armamentarium of the asthma specialist. Omalizumab is a monoclonal antibody (mAb) that binds to IgE, which has been approved for patients with refractory allergic asthma that has been shown to decrease exacerbations, inhaled corticosteroids, and improved asthma-related quality-of-life measures in refractory asthmatics.Citation12–Citation14 Asthma has long been viewed as a disease by marked eosinophilia, eosinophils in airways secretions, and IgE-mediated inflammation, the pathogenesis of which is thought to be Th-2 driven. An association between eosinophilia and outcomes of asthma severity has been established in several studies,Citation15,Citation16 with eosinophil numbers in induced sputum highest among severe asthmatics.Citation17–Citation20 These findings support previous evidence that link airway inflammation and abnormal airway physiology indicating that reducing airway inflammation with corticosteroids improves airway function. The classic eosinophilic pathogenesis of asthma does not adequately explain the subgroups of asthma. For example, noneosinophilic (atypical Th-2 profile) asthma is more likely to have neutrophils and may be relatively corticosteroid resistant; a distinction between this subgroup is important, especially when providing a thoughtful and effective approach in treatment.

In the early 1990s, Djukanovic et alCitation21 were able to exhibit markers of airway inflammation and airway remodeling in bronchial lavage and bronchial biopsies in mild and moderate asthmatics. These findings, in addition to the emerging data on Th-1 and Th-2 subsets of CD4 T-cells, prompted further studies into showing that T-cells in the airways of individuals with asthma had cytokine profiles characteristic of Th-2 cells.Citation15 Thus, specific cytokines such as ILs have since been the primary target for biological inhibition asthma therapy, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, and IL-13 ().

Table 1 Clinical trials with anti-interleukins

Th-2-specific cytokines – IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, and IL-13 – have all been earlier traditionally considered to contribute to the etiology of asthma; they contribute either directly or indirectly to the accumulation of airway and peribronchial eosinophilia. Eosinophils are bone marrow-derived granulocytes that have long been recognized as the main mediator cells in allergic asthma. In addition to releasing varying cytokines and chemokines, they have been found to also release toxic granular proteins, all of which promote Th-2 inflammation and airway epithelial damage.Citation12

It is evident that Th-2 cytokines and its resultant ILs exhibit an imperative role in triggering an inflammatory cascade seen in asthma. Unlike IL-4, IL-9, and IL-13, IL-5 is a key cytokine in eosinophil maturation, activation, survival, and proliferation. As a consequence, the selectivity of IL-5 in the differentiation, activation, recruitment, and survival of human eosinophils have prompted studies to use antibodies against human IL-5.Citation12,Citation22

Activated eosinophils are the cellular source of granules associated with basic proteins,Citation23 reactive oxygen species,Citation24 and lipid mediators,Citation25 which collectively can damage surrounding cells and induce airway hyperresponsiveness and mucus hypersecretion.Citation26,Citation27 Increased numbers of eosinophils in the airways and peripheral blood of subjects with asthma have been shown to correlate with asthma severity.Citation28 Furthermore, scientific literature supports that elevated sputum eosinophil levels are associated with the cause and severity of both asthma and COPD exacerbations.Citation29 Severe eosinophilic asthma is identified by blood eosinophils ≥ 150 cells/µL at initiation of treatment or blood eosinophils ≥ 300 cells/µL in the past 12 months.Citation30 The clinical relevance of eosinophils in asthmatic patients has been confirmed in longitudinal studies demonstrating a reduction in acute exacerbations in subjects who maintained sputum eosinophil counts of < 2%–8%, depending on the specific study.Citation31–Citation33 Besides reflecting the nature of asthma, eosinophilic airway inflammation also suggests decreased responsiveness to anti-inflammatory therapies, particularly with steroids. A subset of patients with refractory asthma have persistent airway eosinophilia despite chronic, high-dose, inhaled corticosteroid treatment.Citation34

Eosinophils have an approximate 3-day turnover rate, with a replacement rate equivalent to the apoptotic rate. With exposure to allergen or parasitic helminth infection, IL-5 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) trigger eosinophil differentiation and expansion. IL-5 derived from allergen-exposed tissues act as a chemotactic agent and increase eosinophil transmigration by increasing β2 integrin-mediated adhesion to endothelial cells. As they are recruited to the affected tissues, the eosinophils are stimulated with IL-33, IL-3, IL-5, and GM-CSF, which inhibits Bid-dependent apoptotic signaling, prolonging their survival and resulting in tissue accumulation.

While present in the affected tissues, eosinophils can act as antigen-presenting cells and degranulate, resulting in the upregulation of inflammation. These granules contain cationic proteins, including eosinophil peroxidase, major basic protein, and eosinophil-associated ribonucleases (EARs), and a number of cytokines, chemokines, enzymes, and growth factors, including IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-13, interferon gamma, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, GM-CSF, transforming growth factor-alpha, chemokine C-C motif ligand-5, C-C motif chemokine-11, and chemokine C-X-C motif ligand-5, that promote inflammation and tissue remodeling.

Accumulation of eosinophils in the parenchyma, airway wall, and lumen, characteristic of eosinophilic asthma, is because of the combined effect of increased differentiation of bone marrow-derived progenitor lines, increased recruitment from the blood, and prolonged life span. Particularly, in obese asthmatics, eosinophils appear to be accumulating in the submucosa. This accumulation combined with reduced rates of apoptosis can lead to the accumulation of necrotic and lysis-prone eosinophils and their released granules.

Despite the use of systemic corticosteroids upon discharge, relapse rates at 12 weeks after an acute asthma exacerbation can range from anywhere between 41% and 52%.Citation35 Increases in airway, sputum, and blood eosinophils have been implicated in asthma exacerbations, resulting in emergency department admissions.Citation36,Citation37 Emerging evidence has also been linked to eosinophilic airway inflammation and a poor response to bronchodilators.Citation38 Eosinophilic inflammation, which may be a consequence of IL-5 action, can be mitigated by mepolizumab, an anti-IL-5 agent.

IL-5 is involved in the maturation, differentiation, survival, and activation of eosinophils.Citation39,Citation40 Basophils also express IL-5RαCitation41 and have been shown to be involved in asthma allergen challenges,Citation42,Citation43 cold air challenges,Citation44 asthma exacerbations,Citation45,Citation46 and fatal asthma.Citation47,Citation48 In fact, mepolizumab has been shown to reduce the number of blood and sputum eosinophils as well as the number of subsequent asthma exacerbations.Citation31,Citation32,Citation49,Citation50

Emerging anti-IL-5 therapies in asthma

The aforementioned findings prompted the development of IL-5-neutralizing monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). By reducing blood and sputum eosinophil counts and asthma exacerbations, anti-IL-5 antibody therapy has shown clinical benefit in severe, corticosteroid-requiring asthma associated with sputum eosinophilia. In contrast, a previous study of anti-IL-5 antibodies showed no benefit in the management of milder asthma that was not necessarily eosinophilic. Anti-IL-5 mAb therapy on airway mucosal eosinophil counts was first tested in steroid-naive subjects with mild atopic asthma, in whom intravenous mepolizumab achieved a 55% decrease in airway mucosal eosinophil counts.Citation51 Several trials, including the SIRIUS, MENSA, and DREAM studies, evidenced improved outcomes with intravenous and subcutaneous mepolizumab following a 12-monthly administration of the drug among patients with severe asthma and blood or sputum eosinophilia.Citation22,Citation49,Citation50,Citation52–Citation56 Positive outcomes were reflected by a decrease in the rate of exacerbations, blood and sputum eosinophil levels, improvement in quality of life, and a mean reduction of 50% from baseline in glucocorticoid dose.Citation38,Citation49,Citation54,Citation55 However, IL-5 blockade in subjects with asthma has failed to improve parameters of lung function, symptom scores, and airway hyperresponsiveness despite rapid and near-complete depletion of eosinophils from blood and sputum.Citation55 Decrease in the number of airway and bone marrow eosinophil and basophil precursors only reached 55% and 52%, respectively.Citation51,Citation55 These latter data compare unfavorably with the novel anti-IL-5 agent benralizumab that effected near total depletion. In view of the overall impact of mepolizumab on asthma, in June 2015, the FDA recommended mepolizumab (Nucala, GlaxoSmithKline) for add-on maintenance treatment in patients aged 18 years or above with severe eosinophilic asthma. Mepolizumab is not commercially available at present, although it is under review by regulatory agencies.

In two pivotal Phase III studies (NCT01287039 and NCT01285323), another anti-IL-5 agent, reslizumab (Cinquil, Teva), cut the frequency of clinical asthma exacerbations by at least half, that is, 50% and 60%, respectively. It proved to be effective in patients inadequately controlled by medium to high doses of inhaled corticosteroid-based therapy. It was also of benefit for asthmatics who had blood eosinophils of 400 cells/µL or higher and one or more exacerbations in the previous year. These resultsCitation22,Citation50,Citation56 support the use of reslizumab in patients with asthma and elevated blood eosinophil counts who are uncontrolled on inhaled corticosteroid-based therapy.Citation22 Reslizumab also provided significant improvement in lung function and other secondary measures of asthma control when added to an existing inhaled corticosteroid-based therapy.Citation50 Pending full analysis of the data, these positive results pave the way for reslizumab regulatory submissions planned for the first half of 2015. FDA ruling on the use of benralizumab in severe asthma is expected by March 2016 ().

The mode of action of benralizumab

Eosinophils are a key target in inflammatory respiratory diseases such as asthma and in some instances of COPD. Many functions of eosinophils and basophils are driven by IL-5. Eosinophils rapidly undergo apoptosis in the absence of IL-5 or other eosinophil-active cytokines. Benralizumab, also known as MEDI-563, is a novel investigational mAb in the management of asthma and COPD. It has a unique mode of action. It binds to the α chain of the IL-5 receptor (IL-5Rα), a receptor expressed by mature eosinophils, eosinophil-lineage progenitor cells, and basophils.Citation40 Benralizumab is a humanized, recombinant, afucosylated IgG1κ mAb. In other words, it has been engineered without a fucose sugar residue in the CH2 region. Afucosylation enhances the interaction of benralizumab with its binding site and thus heightens antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) functions by >1,000-fold over the parental antibody.Citation31,Citation41,Citation57–Citation59 Afucosylated IgG 1 mAbs have a high-binding affinity to the FcgRIIIa region, and they can overcome the inhibitory effects exhibited by serum IgG, which limit the ADCC activity of their fucosylated counterparts.Citation60 Other anti-IL-5 mAbs (eg, mepolizumab and reslizumab) act by neutralizing the effects of IL-5 and block the activation of eosinophils by IL-5. However, when compared to the other anti-IL-5 biologics, benralizumab targets the effector cells themselves that are circulating and lung-tissue resident tissue eosinophils and basophils. Benralizumab not only blocks all the recruitment, activation, and mobilization of eosinophils but it also allows the depletion of eosinophils in the circulation, bone marrow, and target tissues, particularly airways and lungs in asthmatics.Citation61 By acting on the IL-5 receptor by ADCC, benralizumab decreases blood eosinophils and basophils close to the limit of detection and reduces eosinophil precursors in the bone marrow by 80% or more.Citation41 Therefore, benralizumab might provide a more complete depletion of airway eosinophils and basophils through enhanced ADCC and subsequently effect in greater reductions of asthma exacerbations and possibly improvements in other clinical expressions of asthma. This makes benralizumab potentially more effective than the mAb against IL-5 itself, which allows only passive removal of IL-5.

Clinical trials, asthma, and benralizumab

The first, Phase I clinical trial on benralizumab in asthma was completed in 2008 (NCT00512486). A multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial looked into the effects of benralizumab on eosinophil counts in airway mucosal/submucosal biopsy specimens, sputum, bone marrow, and peripheral blood.Citation61 Two patient cohorts were administered either as a single intravenous or multiple subcutaneous doses of benralizumab. Both intravenous and subcutaneous benralizumab reduced eosinophil counts in airway mucosa, submucosa, and sputum. In a similar fashion to mepolizumabCitation51 and reslizumab,Citation50 the study with benralizumab also reported blood eosinophil count reductions of 100%. Single intravenous administrations of benralizumab resulted in marked peripheral blood eosinopenia within 24 hours of dosing, lasting up to 3 months.Citation57 In contrast, peripheral blood eosinophil depletion can be achieved only gradually with mepolizumab, with a peak reached at 4 weeks after dosing. Actually, intravenous mepolizumab doses only resulted in a 52% reduction in bone marrow eosinophil counts,Citation51 whereas benralizumab was able to suppress eosinophil counts in bone marrow and peripheral blood to undetectable levels. The greatest benefits were seen in patients with blood eosinophil levels ≥400 cells/µL, who exhibited significant improvement in annual exacerbation rates, lung function, and asthma score with benralizumab treatment. Benralizumab also demonstrated an acceptable safety profile, with only minor adverse events. The most common ones included nasopharyngitis, headache, and nausea. No adverse events were documented apart from nasopharyngitis and injection site reactions. In fact, there have been no safety concerns to date with benralizumab in Phase I, II, and III trials in asthma.Citation57

A Phase II, multicenter, randomized, double-blind clinical trial completed in 2011 looked into the ability of one intravenous dose of benralizumab to reduce recurrence after acute asthma exacerbations poorly responsive to initial therapy (NCT00768079).Citation62 The study enrolled 110 adults with acute asthma exacerbations necessitating urgent admission into the emergency department. Participants in the study were given a single intravenous infusion of either benralizumab or placebo added to current standard of care with bronchodilators and systemic corticosteroids. Treatment with benralizumab translated into a reduction in the rate and severity of asthma exacerbations up to 12 weeks post-ED admission. In fact, antieosinophilic therapy reduced exacerbation rates by 49% and exacerbations resulting in hospitalization by 60%. These results suggest that there is a persistent effect of a single dose of benralizumab on exacerbations lasting beyond 12 weeks, with noticeable effects up to 24 weeks. This is significant when compared to a course of systemic corticosteroids administered in an emergency setting to reduce asthma exacerbations lasting only for 3 weeks.Citation63 Benralizumab also produced a long-lasting reduction of bloodCitation57 and airwayCitation61 eosinophils to levels and duration that cannot be achieved by current standard therapy. Patients who are frequently admitted to the ED with asthma exacerbations have often been described as having incomplete adherence to post-ED controller agents. The sustained depletion of eosinophils by benralizumab is independent of compliance with standard-of-care oral and/or inhaled asthma therapy. Health care utilization was reduced in subjects treated with benralizumab who presented to the ED with an asthma exacerbation. Benralizumab had no impact on other outcomes, such as the proportion of subjects who experienced one or more subsequent exacerbations. No changes were identified in pulmonary function tests, asthma control, and self-reported quality of life. As opposed to common assumption that benralizumab would have greater effect on eosinophilic exacerbations, this study demonstrated a clinical response to benralizumab regardless of blood eosinophil count.

Encouraging Phase IIb data on benralizumabCitation22,Citation56 from August 2013 revealed that in the setting of uncontrolled severe asthma and elevated baseline eosinophil counts, benralizumab can achieve a significant reduction in asthma exacerbation rate. The study recruited patients with uncontrolled asthma using medium-dose or high-dose, inhaled corticosteroids and LABA for at least 12 months before the screening. Patients were then selected on the basis of two to six exacerbations in the past year that required use of a systemic corticosteroid burst. Benralizumab reduced asthma attacks by approximately 40%–70%, depending on the dose received and baseline eosinophil numbers. In fact, the study showed that benralizumab resulted in fewer asthma exacerbations for a subgroup with higher baseline blood eosinophils. The study also met its secondary end points reflected by improvements in asthma control and lung function as measured by FEV1 over a period of 1 year. Confirming previous literature on the ability of benralizumab to deplete blood and airway eosinophils, benralizumab decreased blood eosinophil levels after the first dose. The investigators used a baseline blood eosino-phil cutoff value for the study of at least 300 cells/µL, which is a good biomarker value to identify patients with asthma who may benefit from benralizumab. In conclusion, this randomized, controlled, double-blind, dose-ranging study revealed that in adults with uncontrolled eosinophilic asthma, benralizumab at 20 mg and 100 mg doses reduces asthma exacerbations and baseline blood eosinophils of at least 300 cells/µL, and improves lung function and asthma control.

Phase II studies consistently confirm that benralizumab is able to cut exacerbation rates compared with placebo. The efficacy and safety data from benralizumab Phase II study support the launching of a Phase III Windward program for benralizumab in the management of severe asthma. The Windward program is extensive; it consists of a number of Phase III clinical trials, including CALIMA, SIROCCO, PAMPERO, ZONDA, GREGALE, and BORA. The first study is the CALIMA trial (NCT01914757); it is designed to determine whether subcutaneous benralizumab reduces the number of exacerbations in patients with uncontrolled, severe asthma receiving a double controller regimen of medium-to-high-dose inhaled corticosteroids and a LABA, with or without oral corticosteroids and additional asthma controllers. The CALIMA trial also aims to assess the impact of benralizumab on lung function, asthma symptoms, and other asthma control measures, as well as emergency room visits and hospital admissions due to asthma exacerbations. The trial design includes a personalized health care strategy in patients with eosinophila. Patients will be followed for 56 weeks, and the study is expected to be completed in March 2016.

As mentioned earlier, besides CALIMA, the Windward program includes other Phase III clinical trials as well. Asthma exacerbation rates are currently being examined for benralizumab used in conjunction with high- (SIROCCO) or medium- (PAMPERO) dose inhaled corticosteroids plus a LABA. AstraZeneca will also conduct an oral corticosteroid-reducing trial ZONDA (NCT02075255) to determine the efficacy in reducing oral steroids while on benralizumab. The GREGALE study (NCT02417961) assesses the functionality, reliability, and performance of an accessorized prefilled syringe with benralizumab administered subcutaneously in an at-home setting. Finally, the long-term safety of benralizumab will be examined in a study called BORA (NCT02258542), estimated to end in June 2018.

Clinical trials, COPD, and benralizumab

Although predominantly associated with elevated neutrophils, elevated levels of eosinophils have also been associated with the cause and severity of COPD exacerbations. Out of the 210 million people suffering from COPD globally, 10%–20% shows evidence of eosinophilic airway inflammation. By depleting blood and sputum eosinophils, benralizumab may also have a role in the management of COPD. The mode of action of benralizumab in COPD is controversial, but several possibilities exist. It has been well documented that a subset of patients with COPD may also have underlying asthma phenotype features, resulting in the diagnosis of asthma–COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS).Citation64 Recently, the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) and the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) issued a joint document that describes ACOS as a clinical entity that resembles features in favor of each diagnosis. Clinically if three or more features of either asthma or COPD are present, the diagnosis of ACOS should be considered. Relevant variables include age at onset, pattern and time course of symptoms, personal history or family history, variable or persistent airflow limitation, lung function between symptoms, and severe hyperinflation. Typically, asthma is a Th-2-driven cytokine pattern resulting in eosinophila, whereas neutrophilic inflammation dominates in COPD.Citation65–Citation67 Although ACOS has not been extensively studied with novel biologics, the utilization of benralizumab may be beneficial, especially in those with predominant eosinophila. Currently, COPD is not characteristically a disease of eosinophila; there are a subset of patients with COPD who may benefit from novel biologics that target the eosinophilic pathway. In clearly defined patients with COPD with no evidence of asthma, 20%–30% of patients show eosinophilia (>3% sputum eosinophils) and eosinophilic bronchitis as evidenced by a sputum database analysis.Citation68 In fact, 18% of patients with COPD with exacerbations actually demonstrate eosinophilia.Citation69

Besides asthma management, Phase II studies turned out to be promising for benralizumab in the treatment of COPD, both in terms of safety and efficacy. In 2013, 101 patients with moderate-to-severe COPD entered a trial on the basis of sputum eosinophilia of at least 3% in the previous 12 months plus at least one acute exacerbation requiring oral corticosteroids, antibiotics, or hospitalization in the past year. The primary end point of the study was to determine if benralizumab reduced acute exacerbations of COPD in patients with eosinophilia and COPD in the course of 1 year. The investigation was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, Phase IIa study (NCT01227278). Study participants received placebo or 100 mg benralizumab subcutaneously, every 4 weeks (three doses), then every 8 weeks (five doses) over 48 weeks. Benralizumab proved to be efficient in significantly improving lung function but had no effect on reducing annualized exacerbation rate in the per-protocol population. However, in the prespecified analyses, the study indicated that inpatient groups of higher baseline levels of blood eosinophils (≥200 cells/µL), benralizumab did reduce COPD exacerbations in a numerical, albeit nonsignificant way. Similar to the per-protocol population, it improved lung function and disease-specific health status. The incidence of adverse events in benralizumab-treated patients, including respiratory disorders (63%) and infections (27%), was comparable to that of placebo groups. Overall, benralizumab failed to reduce the rate of acute exacerbations of COPD compared with placebo but had a positive impact on lung function, quality of life, and COPD symptoms. The results of prespecified subgroup analysis support further investigation of benralizumab in patients with COPD and blood eosinophilia and call for careful identification of eosinophilic phenotypes in COPD (SECOPD). These findings make benralizumab the first biological agent to produce marked reduction in eosinophilic inflammation and beneficial effects in severe eosinophilic COPD.

Insights from Phase II trials prompted the design of Phase III studies for benralizumab in the treatment of COPD. In the setting of the GALATHEA and TERRANOVA trials, benralizumab is currently undergoing Phase III studies to determine if subcutaneous benralizumab reduces COPD exacerbation rate in symptomatic patients with moderate-to-very-severe COPD. Selection criteria include patients receiving standard-of-care therapies, evidence of moderate-to-very-severe COPD, two or more moderate or more than one severe COPD exacerbations requiring treatment or hospitalization in the past year, treatment with double or triple therapy throughout the year before enrollment, and a history of smoking. Health status, quality of life, pulmonary function, respiratory symptoms, rescue medication use, severity, frequency, and duration of exacerbations will be evaluated. These randomized, double-blinded, double-dummy, 56-week, placebo-controlled, multicenter trials are expected to end in the course of 2017.

Benralizumab in the treatment of hypereosinophilic syndrome

Besides the treatment of eosinophilic asthma and COPD, benralizumab seems to be a promising investigational agent in the management of a rare, chronic eosinophilic disorder called hypereosionphilic syndrome (HES). HES consists of peripheral blood eosinophilia with concomitant organ dysfunction in the absence of parasitic, allergic, or other causes of eosinophilia. Although HES can affect any organ, eosinophilic infiltration and mediator release typically causes damage to the heart, lungs, spleen, skin, and nervous system. HES can be categorized into two broad subtypes: the myeloproliferative and lymphoproliferative variant. The myeloproliferative variant is characterized by a chromosomal defect, resulting in the FIP1L1/PDGFRA-associated fusion gene; it may be responsive to treatment with imatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor. In contrast, the lymphoproliferative variant lacks the FIP1L1/PDGFRA-associated fusion gene. It is marked by a clonal population of T-cells with aberrant phenotype and is usually treated with corticosteroids.Citation70 Despite the high proportion of responders to corticosteroid therapy, there are also patients who become relatively refractory to steroids or develop intolerance.

Overproduction of eosinophilopoietic cytokines, such as IL-5, can be one of the underlying mechanisms that can lead to HES. Therefore, investigational agents targeting IL-5 (mepolizumab and reslizumab) or its receptor (benralizumab) can potentially be used as steroid-sparing drugs in the treatment of lymphoproliferative, FIP1L1-PDGFRA-negative HES. A randomized, multicenter trial of 85 patients with HES revealed that mepolizumab allows reduction in glucocorticosteroid dose and is well tolerated and effective as a long-term corticosteroid-sparing agent.Citation52

An ideal alternative option in the management of HES could be the targeting of the IL-5Rα, which is conveniently restricted to eosinophils, basophils, mast cells, and their precursors. The safety and efficacy of benralizumab as an anti-IL-5Rα agent is currently being evaluated in subjects with HES (NCT02130882). Symptomatic patients with HES on stable therapy are being recruited into a Phase IIa randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, ending in August 2016. The primary end point of the study is to determine the reduction in peripheral blood eosinophilia in the setting of stable background therapy at 12 weeks and 1 year. Secondary end points include the reduction of bone marrow eosinophils and mast cells, tissue eosinophilia, improvement in end organ manifestations, the frequency and severity of adverse events, pharmacokinetics, and the development of antidrug antibodies.

Conclusion

The preclinical and clinical studies with benralizumab provide compelling evidence that targeting the IL-5 pathway in eosinophilic conditions such as asthma, COPD, and HES has therapeutic potential. Through the mechanism of ADCC, eosinophils and basophils are actively and effectively depleted after administration of the mAb benralizumab. This mode of action might provide a novel treatment approach in these eosinophilic conditions. At the time of publication, benralizumab is undergoing Phase III clinical trials in both asthma and COPD and Phase II trials in the management of HES. Benralizumab proved to be effective in reducing exacerbation rate in patients with uncontrolled eosinophilic asthma.Citation56 In Phase II studies, benralizumab achieved mixed results in the setting of COPD by effecting a clinically significant improvement in lung function but had no impact on exacerbations.Citation68 In certain forms of HES, anti-IL-5 therapy effectively suppresses blood eosinophils and clinical manifestations of the disease and allows doses of corticosteroids to be tapered. These results seem promising for the potential use of benralizumab in the setting of HES.

Although the overall potential market for anti-IL-5 receptor therapy makes up just a meager 3% of the total asthma population, this group comprises 30% of patients with severe treatment-refractory disease.Citation71 Patients with severe asthma often fail to achieve adequate control despite heavy use of high-dose, inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting bronchodilators.

There is a strong link between severe asthma and high levels of blood, tissue, and sputum eosinophils. Still, no approved treatments exist for patients with severe asthma with predefined eosinophil levels. Benralizumab has the potential to address this pivotal medical question.

The marked heterogeneity of the pathogenesis of asthma calls for careful selection of asthmatic patients for patient-tailored therapies involving IL modulation. Biologics, such as benralizumab, will have to be offered on the basis of phenotyping patients to achieve the best outcome. It is crucial to determine patient subtypes by sputum and/or peripheral blood eosinophilia to figure out who are likely to be responders or nonresponders to targeted therapies.

This paper has also provided a novel algorithm in the evaluation of patients who may benefit from benralizumab. To date, there have been no safety concerns with benralizumab. However, there is much to be explored with regard to the long-term side effects of benralizumab (ie, infection or malignancy). Although it is still years away from potential clinical use, it is hoped that it will be approved for the management of severe, treatment-refractory asthma in the next 5 years. The development prospects for benralizumab are encouraging as a potential innovative personalized medication for exacerbation-prone patients with severe asthma, COPD, and HES inadequately controlled by current standard-of-care therapy.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BarnettSBNurmagambetovTACosts of asthma in the United States: 2002–2007J Allergy Clin Immunol2011127114515221211649

- WoolcockAJSteroid resistant asthma: what is the clinical definition?Eur Respir J1993657437478519386

- ChanMTLeungDYSzeflerSJSpahnJDDifficult-to-control asthma: clinical characteristics of steroid-insensitive asthmaJ Allergy Clin Immunol199810155946019600494

- WoodruffPGModrekBChoyDFT-helper type 2-driven inflammation defines major subphenotypes of asthmaAm J Respir Crit Care Med2009180538839519483109

- MooreWCMeyersDAWenzelSEIdentification of asthma phenotypes using cluster analysis in the Severe Asthma Research ProgramAm J Respir Crit Care Med2010181431532319892860

- BusseWWAsthma diagnosis and treatment: filling in the information gapsJ Allergy Clin Immunol2011128474075021875745

- DweikRABoggsPBErzurumSCAn official ATS clinical practice guideline: interpretation of exhaled nitric oxide levels (FENO) for clinical applicationsAm J Respir Crit Care Med2011184560261521885636

- MartinRJSzeflerSJKingTSThe predicting response to inhaled corticosteroid efficacy (PRICE) trialJ Allergy Clin Immunol20071191738017208587

- National Heart Lung, and Blood InstituteNational asthma education and prevention program, third expert panel on the diagnosis and management of asthmaExpert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma2007 Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK7222/Accessed August 2007

- DenningDWO’DriscollBRPowellGRandomized controlled trial of oral antifungal treatment for severe asthma with fungal sensitization: the Fungal Asthma Sensitization Trial (FAST) studyAm J Respir Crit Care Med20091791111818948425

- BatemanEDIzquierdoJLHarnestUEfficacy and safety of roflumilast in the treatment of asthmaAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol200696567968616729780

- KistemakerLEHiemstraPSBosISTiotropium attenuates IL-13-induced goblet cell metaplasia of human airway epithelial cellsThorax201570766867625995156

- DunnRMWechslerMEAnti-interleukin therapy in asthmaClin Pharmacol Ther2015971556525670383

- BusseWWMorganWJGergenPJRandomized trial of omalizumab (anti-IgE) for asthma in inner-city childrenN Engl J Med2011364111005101521410369

- StrunkRCBloombergGROmalizumab for asthmaN Engl J Med2006354252689269516790701

- FahyJVEosinophilic and neutrophilic inflammation in asthma: insights from clinical studiesProc Am Thorac Soc20096325625919387026

- WoodruffPGKhashayarRLazarusSCRelationship between airway inflammation, hyperresponsiveness, and obstruction in asthmaJ Allergy Clin Immunol2001108575375811692100

- LouisRLauLCBronAORoldaanACRadermeckerMDjukanovicRThe relationship between airways inflammation and asthma severityAm J Respir Crit Care Med2000161191610619791

- HornBRRobinEDTheodoreJVan KesselATotal eosinophil counts in the management of bronchial asthmaN Engl J Med197529222115211551124105

- JansonCHeralaMBlood eosinophil count as risk factor for relapse in acute asthmaRespir Med19928621011041615173

- TaylorKJLukszaARPeripheral blood eosinophil counts and bronchial responsivenessThorax19874264524563660304

- DjukanovicRRocheWRWilsonJWMucosal inflammation in asthmaAm Rev Respir Dis199014224344572200318

- CastroMZangrilliJWechslerMEReslizumab for inadequately controlled asthma with elevated blood eosinophil counts: results from two multicentre, parallel, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trialsLancet Respir Med20153535536625736990

- AyarsGHAltmanLCGleichGJLoegeringDABakerCBEosinophil-and eosinophil granule-mediated pneumocyte injuryJ Allergy Clin Immunol19857645956044056248

- GleichGJThe eosinophil and bronchial asthma: current understandingJ Allergy Clin Immunol19908524224362406322

- ShawRJWalshGMCromwellOMoqbelRSpryCJKayABActivated human eosinophils generate SRS-A leukotrienes following IgG-dependent stimulationNature198531660241501524010786

- GundelRHLettsLGGleichGJHuman eosinophil major basic protein induces airway constriction and airway hyperresponsiveness in primatesJ Clin Invest1991874147014732010556

- CoyleAJAckermanSJBurchRProudDIrvinCGHuman eosinophil-granule major basic protein and synthetic polycations induce airway hyperresponsiveness in vivo dependent on bradykinin generationJ Clin Invest1995954173517407706481

- BousquetJChanezPLacosteJYEosinophilic inflammation in asthmaN Engl J Med199032315103310392215562

- DenteFLBacciEBartoliMLMagnitude of late asthmatic response to allergen in relation to baseline and allergen-induced sputum eosinophilia in mild asthmatic patientsAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol2008100545746218517078

- BrownTFDA panel backs mepolizumab for severe eosinophilic asthmaMedscape Medical News6112015

- GreenRHBrightlingCEMcKennaSAsthma exacerbations and sputum eosinophil counts: a randomised controlled trialLancet200236093471715172112480423

- JayaramLPizzichiniMMCookRJDetermining asthma treatment by monitoring sputum cell counts: effect on exacerbationsEur Respir J200627348349416507847

- ChlumskyJStrizITerlMVondracekJStrategy aimed at reduction of sputum eosinophils decreases exacerbation rate in patients with asthmaJ Int Med Res200634212913916749408

- SilkoffPELentAMBusackerAAExhaled nitric oxide identifies the persistent eosinophilic phenotype in severe refractory asthmaJ Allergy Clin Immunol200511661249125516337453

- LederleFAPluharREJosephAMNiewoehnerDETapering of corticosteroid therapy following exacerbation of asthma. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialArch Intern Med198714712220122033318751

- RestrepoRDPetersJNear-fatal asthma: recognition and managementCurr Opin Pulm Med2008141132318043271

- Bellido-CasadoJPlazaVPerpinaMInflammatory response of rapid onset asthma exacerbationArch Bronconeumol20104611587593 Spanish20832159

- PavordIDHaldarPBraddingPWardlawAJMepolizumab in refractory eosinophilic asthmaThorax201065437020388767

- TakatsuKTakakiSHitoshiYInterleukin-5 and its receptor system: implications in the immune system and inflammationAdv Immunol1994571451907872157

- RothenbergMEHoganSPThe eosinophilAnn Rev Immunol20062414717416551246

- KolbeckRKozhichAKoikeMMEDI-563, a humanized anti-IL-5 receptor α mAb with enhanced antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity functionJ Allergy Clin Immunol2010125613441353.e134220513525

- GuoCBLiuMCGalliSJBochnerBSKagey-SobotkaALichtensteinLMIdentification of IgE-bearing cells in the late-phase response to antigen in the lung as basophilsAm J Respir Cell Mol Biol19941043843907510984

- GauvreauGMLeeJMWatsonRMIraniAMSchwartzLBO’ByrnePMIncreased numbers of both airway basophils and mast cells in sputum after allergen inhalation challenge of atopic asthmaticsAm J Respir Crit Care Med200016151473147810806141

- KauffmannFNeukirchFAnnesiIKorobaeffMDoreMFLellouchJRelation of perceived nasal and bronchial hyperresponsiveness to FEV1, basophil counts, and methacholine responseThorax19884364564613420556

- KimuraIMoritaniYTanizakiYBasophils in bronchial asthma with reference to reagin-type allergyClin Allergy1973321952024131253

- MaruyamaNTamuraGAizawaTAccumulation of basophils and their chemotactic activity in the airways during natural airway narrowing in asthmatic individualsAm J Respir Crit Care Med19941504108610937921441

- KoshinoTTeshimaSFukushimaNIdentification of basophils by immunohistochemistry in the airways of post-mortem cases of fatal asthmaClin Exp Allergy1993231191992510779279

- KepleyCLMcFeeleyPJOliverJMLipscombMFImmunohistochemical detection of human basophils in postmortem cases of fatal asthmaAm J Respir Crit Care Med200116461053105811587996

- NairPPizzichiniMMKjarsgaardMMepolizumab for prednisone-dependent asthma with sputum eosinophiliaN Engl J Med20093601098599319264687

- CastroMMathurSHargreaveFReslizumab for poorly controlled, eosinophilic asthma: a randomized, placebo-controlled studyAm J Respir Crit Care Med2011184101125113221852542

- Flood-PagePTMenzies-GowANKayABRobinsonDSEosinophil’s role remains uncertain as anti-interleukin-5 only partially depletes numbers in asthmatic airwayAm J Respir Crit Care Med2003167219920412406833

- BelEHWenzelSEThompsonPJOral glucocorticoid-sparing effect of mepolizumab in eosinophilic asthmaN Engl J Med2014371131189119725199060

- OrtegaHGLiuMCPavordIDMepolizumab treatment in patients with severe eosinophilic asthmaN Engl J Med2014371131198120725199059

- PavordIDKornSHowarthPMepolizumab for severe eosinophilic asthma (DREAM): a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialLancet2012380984265165922901886

- HaldarPBrightlingCEHargadonBMepolizumab and exacerbations of refractory eosinophilic asthmaN Engl J Med20093601097398419264686

- CastroMWenzelSEBleeckerERBenralizumab, an anti-interleukin 5 receptor α monoclonal antibody, versus placebo for uncontrolled eosinophilic asthma: a phase 2b randomised dose-ranging studyLancet Respir Med201421187989025306557

- BusseWWKatialRGossageDSafety profile, pharmacokinetics, and biologic activity of MEDI-563, an anti-IL-5 receptor α antibody, in a phase I study of subjects with mild asthmaJ Allergy Clin Immunol2010125612371244.e220513521

- GhaziATrikhaACalhounWJBenralizumab – a humanized mAb to IL-5Rα with enhanced antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity – a novel approach for the treatment of asthmaExpert Opin Biol Ther201212111311822136436

- WalshGMEosinophil apoptosis and clearance in asthmaJ Cell Death20136172525278777

- IidaSMisakaHInoueMNonfucosylated therapeutic IgG1 antibody can evade the inhibitory effect of serum immunoglobulin G on antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity through its high binding to FcgammaRIIIaClin Cancer Res20061292879288716675584

- LavioletteMGossageDLGauvreauGEffects of benralizumab on airway eosinophils in asthmatic patients with sputum eosinophiliaJ Allergy Clin Immunol2013132510861096.e523866823

- NowakRMParkerJMSilvermanRAA randomized trial of benralizumab, an antiinterleukin 5 receptor α monoclonal antibody, after acute asthmaAm J Emerg Med2015331142025445859

- RoweBHSpoonerCHDucharmeFMBretzlaffJABotaGWCorticosteroids for preventing relapse following acute exacerbations of asthmaCochrane Database Syst Rev2007183CD00019517636617

- MiravitllesMAlcazarBAlvarezFJWhat pulmonologists think about the asthma-COPD overlap syndromeInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2015101321133026270415

- BujarskiSParulekarADSharafkhanehAHananiaNAThe asthma COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS)Curr Allergy Asthma Rep201515350925712010

- LouieSZekiAASchivoMThe asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap syndrome: pharmacotherapeutic considerationsExpert Rev Clin Pharmacol20136219721923473596

- PostmaDSRabeKFThe asthma-COPD overlap syndromeN Engl J Med2015373131241124926398072

- BrightlingCEBleeckerERPanettieriRAJrBenralizumab for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and sputum eosinophilia: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2a studyLancet Respir Med201421189190125208464

- SoterSBartaIAntusBPredicting sputum eosinophilia in exacerbations of COPD using exhaled nitric oxideInflammation20133651178118523681903

- ValentPKlionADHornyHPContemporary consensus proposal on criteria and classification of eosinophilic disorders and related syndromesJ Allergy Clin Immunol20121303607612.e922460074

- ThamrinCTaylorDRJonesSLSukiBFreyUVariability of lung function predicts loss of asthma control following withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroid treatmentThorax201065540340820435861