Abstract

Pernicious anemia (also known as Biermer’s disease) is an autoimmune atrophic gastritis, predominantly of the fundus, and is responsible for a deficiency in vitamin B12 (cobalamin) due to its malabsorption. Its prevalence is 0.1% in the general population and 1.9% in subjects over the age of 60 years. Pernicious anemia represents 20%–50% of the causes of vitamin B12 deficiency in adults. Given its polymorphism and broad spectrum of clinical manifestations, pernicious anemia is a great pretender. Its diagnosis must therefore be evoked and considered in the presence of neurological and hematological manifestations of undetermined origin. Biologically, it is characterized by the presence of anti-intrinsic factor antibodies. Treatment is based on the administration of parenteral vitamin B12, although other routes of administration (eg, oral) are currently under study. In the present update, these various aspects are discussed with special emphasis on data of interest to the clinician.

Introduction

Hypovitaminosis B12 is common in adults and in elderly patients with a prevalence ranging from 15%–40% according to the various studies and definition used.Citation1 It is often underdiagnosed because of subtle or polymorphous clinical manifestations. Its main etiology is represented by classic pernicious anemia (PA), also known as Biermer’s disease.Citation2

PA is an autoimmune atrophic gastritis that causes a deficiency in vitamin B12 due to its malabsorption.Citation3 It accounts for 20%–50% of the documented causes of vitamin B12 (cobalamin) deficiency in adults according to a recent series.Citation4 In the general population, the prevalence of PA is 0.1%; in subjects over the age of 60, it reaches 1.9%.Citation5,Citation6 It often poses diagnostic and therapeutic challenges to the clinician.

In recent years, this disease has gained renewed interest both in regard to its pathogenesis and clinical features as well as to its diagnosis and treatment. In the present update, these aspects will be discussed with a special emphasis on data of interest to the clinician.

Elements of pathogenesis for the clinician

Pathologically, PA is characterized by at least the following elements:

– The destruction of the gastric mucosa, especially fundic, by a process of cell-mediated autoimmunity.Citation6,Citation7

– A fundic atrophy accompanied by a reduction in gastric acid secretion, a reduction in intrinsic factor (IF) secretion, and vitamin B12 malabsorption, which is corrected by the addition of IF.Citation8,Citation9

– The presence of various antibodies, including antibodies detectable in both plasma and gastric secretions in the form of anti-IF antibodies and antigastric parietal cell (anti-GPC) antibodies, the latter being specifically directed against the hydrogen potassium adenosine triphosphatase (H+/K+-ATPase) proton pump.Citation8

PA-associated type A atrophic gastritis is restricted to the fundus and gastric body. Early lesions are characterized by chronic inflammation in the submucosa that extends into the lamina propria of the mucosa between gastric glands, with a loss of both gastric and zymogene cells.Citation3,Citation7–Citation9 In advanced stages of the disease, gastric atrophy is recognizable macroscopically. The architecture of the gastric body and fundus is comparable to newsprint paper because of the dramatic reduction or absence of gastric glands. In particular, the parietal cells and zymogenic cells are absent from the gastric mucosa and are replaced by intestinal metaplasia.Citation7–Citation9

A major breakthrough in understanding the pathogenesis of type A atrophic gastritis has been the identification of the gastric enzyme H+/K+-ATPase as the target antigen recognized by anti-GPC antibodies.Citation10,Citation11 This proton pump is responsible for acid secretion in the stomach and is the major protein of the secretory canaliculi of GPCs. The H+/K+-ATPase molecule is a heterodimer consisting of a 92 kDa α subunit and a highly glycosylated β subunit with an apparent molecular weight of 60–90 kDa.

Experimental murine models have contributed significantly to the knowledge of the pathogenesis of autoimmune gastritis. The studies have shown that gastritis is caused by the action of lymphocyte cluster of differentiation-4 T-helper cell-1 inflammatory cells, directed against α and β subunits of this enzyme.Citation7–Citation9 They are responsible for the damage to the gastric mucosa. The β subunit is the causal antigen and source of the autoimmune response.

The potential role of Helicobacter pylori in the pathogenesis of autoimmune gastritis and PA has been explored and postulated in recent years.Citation3,Citation7 These studies have been largely based on the presence of anti-GPC antibodies in individuals who are infected with H. pylori. However, because of the wide prevalence of infection by H. pylori in the human population, it is difficult to infer and/or conclude that all infected individuals will develop an autoimmune gastritis. This is especially true given that recent murine studies on the association between H. pylori and autoimmune gastritis are inconclusive.Citation9 There are, however, a few disconcerting clinical observations in which an affiliation (or at least a link) was noted between H. pylori and PA, an association that will need to be documented or refuted in the future.Citation12

From a clinical standpoint, it should also be noted that serologic testing for H. pylori is negative in advanced stages of PA, since the growth of this organism is not optimal in an alkaline environment (in the presence of immune atrophy associated with achlorhydria).Citation4

Antibodies and their clinical interest

Anti-GPC antibodies, directed against the H+/K+- ATPase (or gastric proton pump) antigen located in the secretory canaliculi of parietal cells and in gastric microsomes, are present at a high frequency of approximately 80%–90%, especially in early stages of the disease.Citation3,Citation6 They are, however, unspecific and can be found at low frequency in other autoimmune diseases (eg, Hashimoto’s disease or diabetes) or in elderly subjects, even those free of any atrophic gastritis.Citation13

In the later stages of the disease, the incidence of anti-GPC antibodies decreases due to the progression of autoimmune gastritis and a loss of GPC mass, as a result of the decrease in antigenic rate. In recent studies, an average incidence of 55% of anti-GPC antibodies was documented in patients with advanced PA.Citation7

Anti-IF antibodies do not appear to have a clearly defined pathogenic role in the development of gastritis.Citation7,Citation8 By contrast, they have a well-documented role in the onset of PA, via the vitamin B12 deficiency they induce. Two types of autoantibodies have been described:

– the blocking autoantibodies (type I), which inhibit the binding of vitamin B12 to the IF and thereby prevent the formation of the vitamin B12/IF complex; and

– the binding autoantibodies (type II), which bind to IF-vitamin B12 complexes, thus preventing their absorption by the intestinal mucosa. They are found in one-third of cases and only in patients who already have anti-type I antibodies.Citation14

With regard to diagnostic performance using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay test, sensitivity is low for anti-IF antibodies, in the order of 37% in the most recent studies (50% in the authors’ experience) while specificity is 100%; for anti-GPC antibodies, sensitivity is in the order of 81.5% while specificity is at 90.3% (sensitivity of 50% and specificity of >98% in the authors’ experience).Citation1,Citation4 The combination of both antibodies for PA yields 73% sensitivity and 100% specificity.Citation15

Clinical manifestations

Anemia is the most frequently encountered clinical sign during PA, together with accompanying functional manifestations, depending on their severity.Citation1,Citation4,Citation5,Citation16 It can often include a hemolytic component with subicterus.Citation16 Other hematological manifestations have also been commonly reported: neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, pancytopenia, intramedullary hemolytic component due to ineffective erythropoiesis, and pseudothrombotic microangiopathy.Citation17 summarizes these various manifestations.Citation1,Citation16 The most frequent signs are the presence of macroovalocytes and hypersegmented neutrophils on peripheral blood smears.Citation16

Table 1 Elements of the hematological manifestations of vitamin B12 deficiency

It should also be noted at this juncture that incipient PA may be associated in young women with a tendency for microcytosis due to iron deficiency linked to achlorhydria-induced iron malabsorption, menstrual bleeding, and a failure to exhaust the 10-year reserves of vitamin B12.Citation17

Glossitis (Hunter’s glossitis) – characterized by a slick or bald tongue, papillary atrophy, and burning sensation on contact with certain foods – is usually associated with this disease, although much less described in a recent series devoted to PA.Citation4

Vitamin B12 deficiency can be responsible for neurological impairment, which can occur in the absence of any anemia or macrocytosis (30% of PA cases). Neurological signs usually generate a clinical picture of combined sclerosis of the spinal cord. Disorders are usually predominant in the lower limbs.Citation18–Citation20 Large nerve fiber damage is responsible for ataxia, paresthesia, tendinous areflexia, and deep sensitivity disorders with Romberg’s signs. However, neurological signs are inconsistent along with a highly variable clinical spectrum ranging from optic neuritis to manifestations of depression. It should also be kept in mind that neurological manifestations may only partially regress despite prolonged and high-dose vitamin B12 therapy, leading to – at times – irreversible sequelae.Citation1,Citation4 In this regard, the role of vitamin B12 deficiency in clinical manifestations of dementia (pseudoAlzheimer’s) is far from consensus, with data from interventional studies being somewhat unconvincing.Citation21

Lastly, summarizes other clinical manifestations in addition to the classic manifestations of PA, eg, thromboembolic events, atherothrombosis with cardiac (myocardial infarction) and brain (ischemic stroke) impairments via hyperhomocysteinemia, fertility problems, and recurrent abortions.Citation1,Citation4,Citation5 Thus, given its polymorphism and broad spectrum of clinical manifestations, PA appears as a potential new “great pretender.”

Table 2 Main clinical manifestations of vitamin B12 deficiency

Association with other autoimmune diseases

Genetic susceptibility to PA appears to be genetically determined, although the mode of inheritance remains unknown. Evidence for the role of genetic factors includes familial co-occurrence of PA and its association with other autoimmune diseases.Citation22 Thus, a certain number of autoimmune diseases occur at a higher frequency in patients with PA – around 30% in the authors’ experience – or among family members of PA patients.Citation4 They can precede the disease or occur after its onset.

The association of PA with autoimmune diseases such as type 1 diabetes (insulin dependent), autoimmune thyroiditis (particularly Hashimoto’s thyroiditis), or vitiligo is common.Citation2,Citation22,Citation23 Other associations have also been frequently described, eg, Sjogren’s syndrome, celiac disease, and Addison’s adrenal insufficiency.Citation2,Citation4,Citation5 Cases of multiple autoimmune syndrome including PA have also been documented.Citation24,Citation25

With regard to susceptibility to PA, the role of the human leukocyte antigen system has been demonstrated for certain loci such as human leukocyte antigen B8 DR3.Citation22,Citation26 Nevertheless, data pertaining to genetic predisposition are still relatively fragmented, preliminary, and/or unconfirmed, eg, role of the AIRE gene. Comprehensive studies are currently ongoing in an attempt to identify other susceptibility genes, notably within the context of familial PA.Citation2

Neoplastic complications

The somewhat subtle progression from autoimmune gastritis to PA can take 20–30 years or even more, given that vitamin B12 stores can last 5–10 years depending on the individual.Citation1 Nonetheless, it should be emphasized that the diagnosis of PA is important, not only because of the consequences of anemia but also because of neurological complications and especially because of a susceptibility to all types of gastric tumors – from common carcinoid tumors to more rare adenoma carcinomas and non-Hodgkin’s malignant lymphomas (of low grade).Citation2 The prevalence of gastric carcinoid tumors in patients with PA varies from 4%–7% depending on the series.Citation5,Citation27

Thus, surveillance by upper endoscopy is recommended, quarterly during the first year in the presence of neoplastic lesions, and less frequently thereafter in the absence of macroscopic or histological recurrence. In the absence of such lesions, biannual endoscopic surveillance is suggested, with multiple biopsies.Citation2,Citation5,Citation27

In PA, gastric carcinoid tumors are usually low-grade tumors, of fundic origin, multiple in 50% of cases (hence the need for multiple biopsies), and small (<1 cm).Citation27 They can be accompanied by metastases in 16% of cases, without clinical diagnosis of carcinoid syndrome.Citation27

This low-grade malignancy of PA-related gastric carcinoid tumors leads to conservative treatments, eg, limited resection, with three main decision criteria according to Cattan: age, size, and number of tumors.Citation28 Therapeutic abstention is usually recommended in patients > 70 years of age.Citation27,Citation28

Diagnostic criteria of PA

The diagnosis of PA is classically (or historically) established in clinical routine by demonstrating the absence of IF by the study of gastric juice – a rate of secretion of IF < 200 U/hour after stimulation with pentagastrin (normal being >2000 U/hour) is specific to PA;Citation29 or indirectly by performing a Schilling test which highlights abnormal absorption of radioactive cobalamin, which is corrected after administration of IF.Citation2,Citation3,Citation29

The recent disappearance of Schilling tests and the difficulty in finding a laboratory able to assess the secretion of IF have led clinicians to develop alternative diagnostic strategies as illustrated in . Thus, diagnostic criteria have changed in recently published studies.Citation1,Citation2 It should nevertheless be kept in mind that the Schilling test and lack of IF secretion remain the gold standard for diagnosis of PA.Citation29

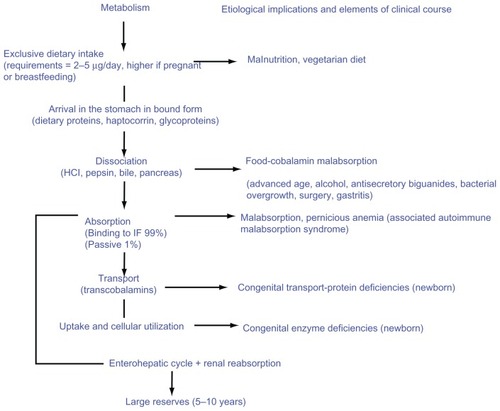

Figure 1 Vitamin B12 metabolism, etiological implications, and elements of clinical course.

Other criteria commonly used to diagnose PA vary in specificity and sensitivity, routine availability, or invasiveness.Citation1 These include:

– The presence of serum anti-IF antibodies for which sensitivity is only 50% (only one out of two patients with true PA has these antibodies).

– The presence of histological lesions of autoimmune fundic gastritis (as discussed above), especially in the absence of H. pylori (in collected samples).

– Hypergastrinemia or increased serum chromogranin A in response to achlorhydria, which strongly points to PA in the absence of proton pump inhibitor use.Citation1,Citation4,Citation5,Citation29

Differential diagnosis of vitamin B12 deficiency

The primary differential diagnosis of vitamin B12 deficiency in adults is food-cobalamin malabsorption (syndrome of nondissociation of vitamin B12 from its carrier proteins), an entity that is the primary etiology of vitamin B12 deficiency in elderly subjects ().Citation1

In practice, this disorder is characterized by an inability to release vitamin B12 from ingested food and/or from intestinal transport proteins, particularly in the presence of hypochlorhydria in which absorption of unbound vitamin B12 is normal.Citation30,Citation31

Low vitamin B12 intake is uncommon in industrialized countries, aside from strict vegans and newborns of vegan women. Other vitamin B12 malabsorption syndromes comprise the genetic defects of proteins involved in vitamin B12 metabolism such as IF deficiency/defects or transcobalamin II deficiency/defects.Citation1

Ultimately, one should bear in mind that PA is a great pretender due to the similarity of presentation with other clinical conditions that can result in vitamin B12 deficiency. The diagnosis should be considered when faced with any hematological and neurological manifestations.Citation1,Citation32

Treatment of vitamin B12 deficiency and optimal management

In most countries, treatment of vitamin B12 deficiency related to PA is based on parenteral vitamin B12 administered intramuscularly under the form of cyanocobalamin, hydroxocobalamin, or methylcobalamin.Citation33,Citation34 In France, only the former is used for this indication.Citation1 A certain superiority of hydroxocobalamin is nevertheless recognized and related to better tissue uptake and storage than the other forms.Citation34

Attitudes regarding the dosage and frequency of administration are very different from one group to another.Citation34 In the United States and the United Kingdom, the doses range from 100–1000 μg/month for life.Citation33,Citation34 In France, cobalamin therapy involves acute treatment at a dose of 1000 μg daily for 1 week, followed by 1000 μg per week for 1 month, then a monthly dose of 1000 μg for life.Citation2,Citation34

With regard to curative treatment by orally administered cobalamin (1% of free vitamin B12 is absorbed passively, independently of the IF and of its receptor [cubilin]), a therapeutic scheme has yet to be definitely validated, given the present state of knowledge.Citation34 In PA, the doses conventionally administered should in all cases greatly exceed those required physiologically, ranging from 1000–2000 μg/day of cyanocobalamin.Citation35,Citation36 In the authors’ experience of oral administration, this therapeutic mode should be reserved for primarily hematological consequences of vitamin B12 deficiency. Currently, it is always recommended to use the parenteral route in severe neurological forms. Alternatively, the oral route could curtail or avoid the inconvenience related to discomfort of injections and of likely higher costs (nursing care).Citation34 It can also be particularly useful in patients under anticoagulant or antiplatelet agent therapy in whom intramuscular injections are contraindicated.Citation34

On a final note, the authors would like to draw the attention of the field practitioner to the need for annual monitoring of these patients to ensure therapeutic adherence (the vitamin has to be administered for life) and to detect neoplastic complications of PA (endoscopy at least twice yearly in the absence of detectable lesions) as well as associations with other autoimmune disorders. This latter surveillance can be done without the need for a systematic comprehensive assessment but rather by tracking all abnormal complaints or clinical signs.

Disclosure

Professor Andres is a member of the National Commission of Pharmacovigilance. The data developed herein are solely his personal opinion. He is responsible for the Centre de Competences des Cytopenies Auto-Immunes de l’Adulte (Competence Center of Autoimmune Cytopenia in Adults) at the University Hospital of Strasbourg. He leads a working group on vitamin B12 deficiency at the University Hospital of Strasbourg (CARE B12) and is a member of GRAMI: Groupe de Recherche sur les Anemies en Medecine Interne (Research Group on Anemia in Internal Medicine). He is an expert consultant to several laboratories involved in hematology (Amgen, Roche, Chugai, GSK, Vifor Pharma, Ferring, Genzyme, Actelion, Given Imaging) and has participated in numerous international and national studies sponsored by these laboratories or to academic works. The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- AndresELoukiliNHNoelEVitamin B12 (cobalamin) deficiency in elderly patientsCMAJ2004171325125915289425

- AndresEAffenbergerSVinzioSNoelEKaltenbachGSchliengerJLCobalamin deficiencies in adults: update of etiologies, clinical manifestations and treatmentRev Med Interne20052612938946 French15951065

- ZittounJBiermer’s diseaseRev Prat2001511415421546 French11757269

- LoukiliNHNoelEBlaisonGUpdate of pernicious anemia. A retrospective study of 49 casesRev Med Interne2004258556561 French15276287

- CarmelRPernicious anemiaJohnsonLREncyclopedia of GastroenterologyWaltham, MAAcademic Press2004170171

- TohBHvan DrielIRGleesonPAPernicious anemiaN Eng J Med19973372014411448

- TohBHAlderuccioFPernicious anaemiaAutoimmunity200437435736115518059

- TohBHWhittinghamSAlderuccioFGastritis and pernicious anemiaAutoimmune Diseases200639527546

- AlderuccioFSentryJWMashallACBiondoMTohBHAnimal models of human disease: experimental autoimmune gastritis – a model for autoimmune gastritis and pernicious anemiaClin Immunol20021021485811781067

- TohBHSentryJWAlderuccioFThe causative H+/K+ ATPase antigen in the pathogenesis of autoimmune gastritisImmunol Today200021734835410871877

- D’EliosMMBergmannMPAzzuriAH+K+ATPase (proton pump) is the target autoantigen of Th1-type cytotoxic T cells in autoimmune gastritisGastroenterology2001120237738611159878

- AndresENoelEHenoun LoukiliNCocaCVinzioSBlickleJFIs there a link between the food cobalamin malabsorption and the pernicious anemia?Ann Endocrinol (Paris)2004652118120 French15247870

- EyquemADe Saint MartinJAnticorps anti-estomac [Anti-stomach antibodies]Rev Franc Allergol197111239248 French

- AbsalonYBDubelLJohanetCDosage des anticorps anti-facteur intrinseque: etude comparative RIA-ELISA [Determination of anti-intrinsic factor antibodies: comparative study between ELISA and RIA technologies]Immunoanal Biol Spec19949246249 French

- LahnerEAnnibaleBPernicious anemia: new insights from a gastroenterological point of viewWorld J Gastroenterol200915415121512819891010

- FedericiLHenoun LoukiliNZimmerJAffenbergerSMaloiselFAndresEUpdate of clinical findings in cobalamin deficiency: personal data and review of literatureRev Med Interne2007284225231 French17141377

- GuilloteauMBertrandYLachauxAMialouVLe GallCGirardSPernicious anemia: a teenager with an unusual cause of iron-deficiency anemiaGastroenterol Clin Biol2007311211551156 French18176379

- AndresERenauxVCamposFIsolated neurologic disorders disclosing Biermer’s disease in young subjectsRev Med Interne2001224389393 French11586524

- BeauchetOExbrayatVNavezGBlanchonMAQuangBLGonthierRCombined sclerosis of the spinal cord revealing B12 deficiency: geriatric characteristics apropos of a case evaluated by MRIRev Med Interne2002233322327 French11928381

- MaamarMTazi-MezalekZHarmoucheHNeurological manifestations of vitamin B12 deficiency: a retrospective study of 26 casesRev Med Interne2006276442447 French16540210

- VogelTDali-YoucefNKaltenbachGAndresEHomocysteine, vitamin B12, folate and cognitive functions: a systematic and critical review of the literatureInt J Clin Pract20096371061106719570123

- BankaSRyanKThomsonWNewmanWGPernicious anemia – genetic insightsAutoimmun Rev201110845545921296191

- PerrosPSinghRKLudlamCAFrierBMPrevalence of pernicious anaemia in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus and autoimmune thyroid diseaseDiabet Med2000171074975111110510

- GachesFVidalEBerdahJFSyndromes auto-immuns multiples. A propos de 10 observations [Multiple autoimmune syndrome: about 10 cases]Rev Med Interne1993101165 French

- HumbertPDupondJLMultiple autoimmune syndromesAnn Med Interne (Paris)19881393159168 French3059902

- HrdaPSterzlIMatuchaPKoriothFKrommingaAHLA antigen expression in autoimmune endocrinopathiesPhysiol Res200453219119715046556

- BoudrayCGrangeCDurieuILevratRAssociation of Biermer’s anemia and gastric carcinoid tumorsRev Med Interne19981915154 French9775116

- CattanDAnemies d’origine digestive [Anemia of digestive origin]EMC-Hepato-Gastroenterologie20052124149 French

- CattanDPernicious anemia: what are the actual diagnosis criteria?World J Gastroenterol201117454354421274387

- CarmelRMalabsorption of food cobalaminBaillieres Clin Haematol1995836396558534965

- AndresESerrajKMeciliMKaltenbachGVogelTThe syndrome of food-cobalamin malabsorption: a personal view in a perspective of clinical practiceJ Blood Disord Transfus201122108

- AndresEFedericiLAffenbergerSB12 deficiency: a look beyond pernicious anemiaJ Fam Pract200756753754217605945

- AndresEPerrinAEKraemerJPAnemia caused by vitamin B12 deficiency in subjects over 75 years: new hypotheses. A study of 20 casesRev Med Interne2000211194695411109591

- AndresEFothergillHMeciliMEfficacy of oral cobalamin (vitamin B12) therapyExpert Opin Pharmacother201011224925620088746

- AndresEHenoun LoukiliNNoelEOral cobalamin (daily dose of 1000 μg) therapy for the treatment of patients with pernicious anemia. An open label study of 10 patientsCurr Ther Res2005661322

- KuzminskiAMDel GiaccoEJAllenRHStablerSPLindenbaumJEffective treatment of cobalamin deficiency with oral cobalaminBlood1998924119111989694707