Abstract

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease, leading to death within an average of 2–3 years. A cure is yet to be found, and a single disease-modifying treatment has had a modest effect in slowing disease progression. Specialized multidisciplinary ALS care has been shown to extend survival and improve patients’ quality of life, by providing coordinated interprofessional care that seeks to address the complex needs of this patient group. This review examines the nature of specialized multidisciplinary care in ALS and draws on a broad range of evidence that has shaped current practice. The authors explain how multidisciplinary ALS care is delivered. The existing models of care, the role of palliative care within multidisciplinary ALS care, and the costs of formal and informal care are examined. Critical issues of ALS care are then discussed in the context of the support rendered by multidisciplinary-based care. The authors situate the patient and family as key stakeholders and decision makers in the multidisciplinary care network. Finally, the current challenges to the delivery of coordinated interprofessional care in ALS are explored, and the future of coordinated interprofessional care for people with ALS and their family caregivers is considered.

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as motor neuron disease (MND), is a progressive and terminal neurodegenerative disease. The lifetime risk of developing the condition is 1:400. On average, death results within 2–3 years from symptom onset.Citation1,Citation2 Characterized by heterogeneous patterns of deterioration, presenting symptoms range from falls, limb weakness, communication, and swallowing difficulties to changes in mood, cognition, and behavior.Citation1,Citation3,Citation4 Up to 50% of people with ALS develop some degree of frontotemporal impairment.Citation5,Citation6 Patients may also be at risk of psychological problems such as depression and anxiety, linked to their disease experiences.Citation4,Citation7,Citation8 No cure exists for ALS, and only a small number of treatments (eg, riluzole [pharmaceutical agent], non-invasive ventilation) delay death. Death usually results from respiratory failure. Care delivered and coordinated by multidisciplinary clinics (MDCs) specializing in ALS has been shown to extend survival and improve the quality of life for patients.Citation9,Citation10

To date, reviews of multidisciplinary (also known as interprofessional or interdisciplinary) ALS care have focused on symptom management and on the roles of health professionals in delivering care.Citation11,Citation12 However, such work does not illuminate the wider complexity of processes that underpin service delivery in multidisciplinary ALS care. Challenges to delivering multidisciplinary ALS care include: less than seamless coordination and transition of care between health care professionals across different sectors; patients’ and family members’ evolving expectations of care;Citation13,Citation14 and the lack of support available to health care professionals to deliver evidence-based care to patients and their families.Citation15 Importantly, the roles of the patient, carer, and ALS support associations within the multidisciplinary team have not always been considered. A greater understanding of multidisciplinary care practices and of patients’ and families’ decision-making processes in ALS care can help generate more effective models of care.Citation15

This review draws on a broad base of evidence pertaining to multidisciplinary ALS care, to help decipher how multidisciplinary care is best delivered to ALS patients and their family. First, multidisciplinary ALS care and the evidence that supports the effectiveness of multidisciplinary-based care in ALS are summarized and defined. Then, critical issues in ALS care and how MDCs are positioned to address them are considered. Finally, the challenges to the delivery of multidisciplinary ALS care and the benefits MDC care offers people and families living with ALS are outlined.

What is multidisciplinary care in ALS?

Multidisciplinary care in ALS encompasses the provision of care to the ALS patient and their family by a range of health care disciplines and support services. It is known that multidisciplinary care occurs when professionals who have different skills, knowledge, and experiences work together to achieve optimal care for patients and their families. Given the multitude of physical problems (eg, loss of mobility, respiratory failure, dysarthria, and dysphagia) and psychosocial problems (eg, depression, loss, bereavement, and family distress) posed by ALS, patients and their families engage with a variety of health care disciplines (). To comprehensively address ALS patients’ broad range of needs, multidisciplinary care optimally includes medical practitioners in neurology, respiratory, gastroenterology, rehabilitation, and/or palliative care; allied health care professionals in physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech and language pathology, nutrition and social work; and health professionals in specialist nursing, genetic counseling and psychology, including neuropsychology.Citation10,Citation16,Citation17 Voluntary support services, mostly in the form of national and regional ALS/MND associations, also play an integral role in the delivery of care to patients and their families. In developed countries, the voluntary sector has been shown to coordinate care for ALS patients and supplement the care that patients and their families receive from health services.Citation18–Citation20

Table 1 Multidisciplinary approaches to symptom management

Although multidisciplinary care is not limited to specific care settings or indeed to specialist care, the term “multidisciplinary” in ALS has become synonymous with care provided by MDCs.Citation21–Citation23 Activation of inter-service communication across different care sectors by specialized ALS clinics has proven to be essential for the delivery of high-quality care in ALS.Citation18,Citation24 Linkage between specialized MDCs and community-based services, general practitioner (or family physician), and palliative care services is required, so that by the terminal phase of the disease, many ALS patients and caregivers have experienced multiple encounters with different health care professionals across different health care sectors. Effective delivery of multidisciplinary care in ALS requires seamless collaboration, coordination, and transition between numerous health care professionals within and between disciplines, across a range of health care services and sectors.

Guidelines for the clinical management of ALS have been published in Europe, the UK, and the US.Citation10,Citation16,Citation25 Health professional compliance with these guidelines has been assessed at specialized MDCs, to reveal reasonably high levels of implementation.Citation26 However, patient adherence to health professionals’ recommendations can vary.Citation27 Ideally, patients should be reviewed every 2–3 months at an MDC, with the MDC team maintaining regular contact with the patient and family between visits. Patients should be followed by the same neurologist who in turn should liaise closely with the patient’s primary care physician. Importantly, coordination of the patient’s care requires effective communication between the MDC team, the palliative care team, and community-based services.Citation16,Citation26

Standards in ALS care have been set by specialized ALS clinics.Citation26,Citation28 ALS MDC-based care in the Netherlands has resulted in improved quality of life for patients and greater provision of aids and equipment to patients.Citation29 Specialized ALS MDCs in Italy have increased survival and reduced hospital admissions and length of hospital stay for patients.Citation30 Traynor et alCitation31 found improved survival of 7.5 months, with 1-year mortality being reduced by 30% for patients attending a national ALS clinic in Ireland. Extended survival rates have also been identified in a more recent Irish study focused on the effects of an ALS MDC on patient survival.Citation32 The aforementioned studies reported better outcomes when compared to care that was not multidisciplinary; although, as comparison groups are not always well matched, generalized comparison is difficult. Zoccolella et alCitation33 found that MDC care did not improve survival when compared to general neurology care. However, respiratory and nutritional interventions were low for these groups, and the MDC did not link directly to community-based services or palliative care services.Citation33 It is likely that survival in ALS is influenced by the complex decision-making processes that occur in the multidisciplinary setting, rather than by the effects of symptomatic interventions alone.Citation32

Models of multidisciplinary care in ALS

A coordinated, interprofessional approach to address the needs of ALS patients is represented in several models of care.Citation21–Citation24,Citation34–Citation36 These models share a patient-centered approachCitation37 and recognize that patients and their family members are key stakeholders in care and have active roles in the decision-making process.Citation38,Citation39 Family caregivers are central to the care and support of people with ALS, and they too encounter multiple losses in their caring role. Caring for a person with ALS can be physically and emotionally demanding for family members,Citation40–Citation42 and family caregivers who feel unsupported by health care professionals can experience increased caregiver strain.Citation41 Although family caregivers tend to have a pivotal role in the provision of informal care and support to the patient,Citation43 ALS family caregivers’ needs can be overlooked by service providers.Citation44,Citation45 As for patients, family caregivers in ALS navigate the challenges posed by ALS and assume high levels of responsibility within the ALS care triad (the person with ALS, the family carer, and the health care provider).Citation44,Citation46

Multidisciplinary ALS care is dynamic and has the capacity to adapt to different healthcare contexts. Multidisciplinary ALS care can be provided by publicly or privately funded organizations delivering neurology, rehabilitation, and palliative care services, across primary, secondary, and tertiary care sectors. In many cases, patients and families work with clinicians from different multidisciplinary teams that form their broader ALS-specialized multidisciplinary service – a team within a team. For example, patients may engage with neurology and palliative care-based health professionals who interface at key points along the patient’s trajectory. Care in ALS is most effective when coordinated between specialized MDCs, the community-based sector (including primary care), and palliative care teams.Citation16 Corr et alCitation18 have shown that close liaison between a specialized ALS clinic, community-based services (eg, allied health care professionals, physicians, and homecare services), and the voluntary sector (ie, the local ALS association) can render effective care for ALS patients. In addition, there are potential benefits of specialized nurse coordinators in a liaison role, particularly in the later stages of the disease.Citation47

Multidisciplinary care in ALS is appropriate throughout the disease course (ie, diagnostic, disability, pre-terminal, and terminal phases)Citation24 and is rendered via rehabilitative and palliative approaches to care. “Rehabilitation” is understood in the context of interventions that can assist patients and their families to adapt to the physical and psychological challenges of living with ALS (ie, counseling, social support, alleviation of spasticity, provision of orthotics and appliances, and training in assistive technology), rather than regain the physical loss or remedy the cognitive change encountered by ALS patients.Citation21,Citation48,Citation49 The term “palliative” infers an approach that seeks to alleviate physical, psychological, and existential distress.

The role of palliative care in multidisciplinary ALS care

Palliative care is essential for patients with ALS and their families to ensure their symptoms and issues are clearly identified and appropriately managedCitation50 and to improve the quality of life for patients and their carers.Citation14,Citation51 In ALS, palliative care is appropriate from the time of diagnosis,Citation16,Citation52 especially as the extended duration between symptom onset and diagnosis means many patients are severely disabled by the time they are diagnosed. Members of the palliative care team, led by a specialist palliative care physician, may work in a multidisciplinary context within their own care setting (such as community or home-based palliative care, specialized inpatient and outpatient palliative care facilities). The palliative care team is part of the wider multidisciplinary care approach that traverses the different care sectors involved in delivering services to ALS patients and their families.

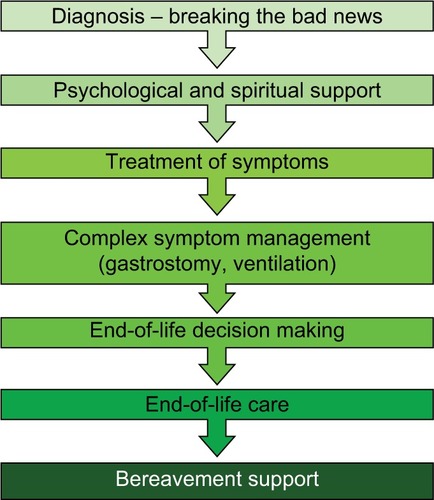

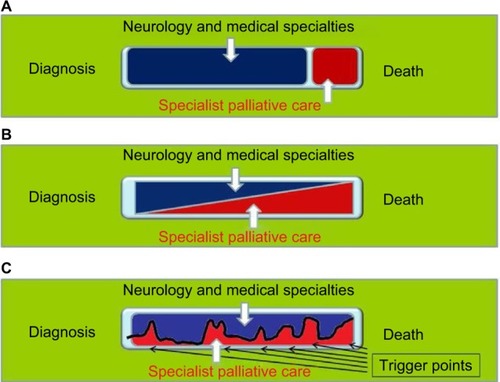

However, few palliative care frameworks have been developed to guide active palliative care engagement in ALS.Citation51 There may be issues within and between the acute care, rehabilitation, and palliative care teams involved, due to the differing attitudes and philosophies of patient care. It is important that there is awareness of and negotiation around these issues to enable well-coordinated care and seamless transition between services.Citation53 Nonetheless, the palliative approach in ALS care can accommodate the evolving needs of the patient and their familyCitation2,Citation51 (). The palliative care needs of patients and their family can vary and fluctuate. The involvement of specialist teams may be episodic, occurring at times of change, crisis, or decision making – for example, at diagnosis, when discussing gastrostomy or ventilatory support, or when change in patient cognition or behavior occurs, which may impact on the timing or appropriateness of decisions at the end of lifeCitation35,Citation51 (). Overall, optimal palliative management of people with ALS and their family requires integrated MDC and palliative- and community-based intervention.Citation54,Citation55

Figure 1 Development of a palliative approach in ALS.

Abbreviation: ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Figure 2 Involvement of palliative care in ALS and other neurological diseases.

Abbreviation: ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

What are the costs of formal and informal ALS care?

Costs associated with ALS care have been evaluated in a number of countries.Citation56–Citation62 MDC-based care has been cost-effective in terms of reducing rates of patient hospitalization.Citation30 Moreover, van der Steen et alCitation56 have shown that the cost of specialized care provided and coordinated by ALS MDCs was no more than the cost of managing ALS through non-specialist services. However, the true cost-effectiveness of formal ALS care is difficult to determine as patients may engage with multiple health care professionals prior to diagnosis.Citation63,Citation64

Connolly et alCitation57 quantified the health and social care costs of ALS in Ireland and found that the largest proportion of costs (72%) arose in community-based care. Seven percent of all costs were attributable to aids and appliances, and only 21% of costs were attributable to services at the national ALS clinic in Ireland. Higher health and social care costs were associated with the use of non-invasive ventilation and gastrostomy and with shorter survival. Depending on the health care system in question, out-of-pocket expenses can also be substantial in ALS care.Citation60,Citation61

A review of the economic impact of ALS has also been undertaken.Citation65 Standardized to the 2015 USD, Gladman and ZinmanCitation65 identified significant variation across 12 developed health care systems in the annual cost of care for the ALS patient. Annual cost of care ranged from $13,667 in Denmark to as high as $69,475 in the US. Health care costs associated with ALS were also higher than that of other neurological conditions. Analysis of the social economic costs of ALS in SpainCitation58 found that costs of informal care (ie, non-paid care including care provided by family) extended well beyond the cost of multidisciplinary care. Furthermore, an economic analysis of costs in ALS in AustraliaCitation59 identified that the costs of informal care and support services (eg, aids and appliances) exceeded direct health care system costs (ie, care facility and health care professional costs). Moreover, economic disadvantage through productivity loss is shouldered by family carers, with the Australian economic analysis estimating this cost to be AUD 4.4 million.Citation59

Critical issues in multidisciplinary ALS care

Three critical points in ALS patients’ care journey shape their health care outcomes and their quality of life. These critical points include the timing and delivery of the diagnosis, the accessing of MDC care, and the timing of decisions surrounding symptom management and end-of-life care.

Timing of the diagnosis

Delays in obtaining a diagnosis in ALSCitation66,Citation67 can result in adverse consequences for patients.Citation4,Citation68 Diagnostic delay can occur for several reasons, such as inefficient referral pathways within health care systems, patients not fully recognizing their own symptoms, and a lack of familiarity with ALS among non-ALS physicians.Citation63,Citation68,Citation69 Delays have arisen because of late referral to specialist investigation, inappropriate referral to non-specialist services, and underrecognition of early symptoms by health care professionals.Citation63,Citation68,Citation69 Within the secondary-care sector alone, diagnostic delays can occur when patients are referred by non-specialist physicians (ie, physicians other than neurologists) to other non-specialist physicians before referral onward to neurologists who specialize in ALS.Citation69 Indeed, in a US-based study of diagnostic timelines in ALS,Citation66 more than half of the participants had received an alternative diagnosis before they received a diagnosis of ALS, and each patient had seen multiple physicians before their diagnosis was confirmed. The average diagnostic timeline in ALS has been shown to range between 10 months and 18 months.Citation16,Citation63,Citation66,Citation67,Citation69 Notwithstanding the complex referral trajectory encountered by ALS patients and their families, a fast-track system for diagnosing ALS at a specialized ALS center reduced diagnostic delays when compared to general neurology diagnostic care pathways.Citation69,Citation70 In addition, a “red flag” tool has also been developed in the UK to facilitate timely referral to specialist services.Citation71

Giving and receiving the diagnosis

The giving and receiving of a terminal diagnosis is a difficult and distressing event for health professionals, patients, and families. In a recent Australian-based study, neurologists at ALS MDCs were judged by patients and family caregivers as doing better in disclosing the diagnosis when compared to neurologists in non-MDC settings’.Citation13,Citation44,Citation72 Neurologists based in MDC settings adhered more to international guidelinesCitation16 on disclosure than did neurologists from non-MDC settings.Citation72 Of note, the time spent giving the diagnosis to patients was significantly longer for the MDC group – an average of 23 minutes for non-MDC clinicians and twice as long for those in MDCs (45 minutes).Citation72 Family members were more likely to be present when the diagnosis was disclosed by MDC-based neurologists. Moreover, coordinated and interprofessional care was more likely to be facilitated by MDC-based neurologists.Citation72

Accessing specialized ALS services

ALS patients have reported difficulty accessing interdisciplinary care in community-based settings without assistance from specialized MDCs.Citation73 However, patients’ attendance at MDCs varies within and between countries. Population-based comparative studies between specialized ALS clinics and general neurology clinics in ItalyCitation30,Citation33 show that between 43% and 66% of people with ALS access specialized ALS clinics. Approximately 80% of ALS patients in Ireland attend one national ALS clinicCitation32 and an estimated 85% of patients with ALS in the Netherlands attend the national ALS Centre.Citation74 In Australia, patients attend one of 10 clinics located in six state capitals; however, rates of attendance are undocumented. A survey of ALS patients in the US revealed that 78% of respondents attended a specialized ALS MDC,Citation75,Citation76 whereas in the UK it is estimated that 70% of ALS patients access MDCs.Citation77

Stephens et al’s study of multidisciplinary ALS clinic use in the USCitation76 reported patient perspectives on the benefits and barriers to attending specialized ALS clinics. Access to integrated care and the potential to engage in research, including clinical trials, were valued by patients. However, the long duration of MDC visits and patients’ reluctance to travel long distances to MDCs also limited the attendance for some patients. The European Federation of Neurological Societies (EFNS) guidelines recommend that more frequent reviews for patients at MDCs in the months following diagnosis or in the later stages of disease may be needed, with less frequent review if the disease is progressing slowly for patients.Citation16 In the US, 3-monthly visits by ALS patients to large MDCs are common.Citation62 Nevertheless, for a proportion of patients, an MDC visit may be a single occurrence only.

Few large-scale studies have captured the journey that patients and their families travel from symptom onset to specialized multidisciplinary ALS care. Galvin et alCitation63 conducted a retrospective exploratory study that tracked ALS patients’ paths to a specialized ALS clinic. The average time from symptom onset to attendance at the MDC was 19 months. The first point of contact for ALS patients in health care services was invariably a general practitioner. Even so, patients also had multiple consultations with other services in primary and secondary care (eg, accident and emergency, other neurology services, and individual allied health care professionals) before they received a diagnosis or attended the clinic. Patients’ consultations with disciplines prior to diagnosis or attendance at the MDC clinic tended not to be coordinated between disciplines. However, most MDCs are located in metropolitan regions and in large tertiary hospitals or centers and may not be accessible to some patients and their family. Moreover, health care organization funding may limit the availability of services to patients living outside their catchment area or geographical boundary. Patients who live a long distance from an MDC may be at a disadvantage in the latter stages of the disease, particularly when fatigue and mobility restrictions increase for them.Citation76

The use of tele-health has the potential to offset some of the logistical difficulties associated with accessing specialized ALS clinics. Where patients are unable to physically access the MDC, tele-health can enable the MDC team to interface with patients and their family in the home environment.Citation77,Citation78 In addition, tele-health has the potential for local and community-based services to engage with the MDC in real time and to partner the MDC in the decision-making process.Citation77,Citation78 In the case of respiratory care, the benefits of tele-health for ALS patients have been reported.Citation79,Citation80 The setting and monitoring of invasiveCitation81 and non-invasive ventilationCitation82 where the parameters for clinical assessment can be downloaded from a remote location have strong application in a tele-health model of care. Tele-health can be provided to ALS patients in conjunction with or as follow-up to face-to-face visits with patients.Citation80 Continuity of care and of symptom management are specific advantages of tele-health for ALS patients,Citation78 and both patients and clinicians in ALS care have been shown to be receptive to tele-healthCitation80,Citation81 One study showed that tele-health for ALS care impacted positively on health care utilization, patient survival, and patient functional status.Citation82 Nurse-led tele-health may also be beneficial if initiated in the later stages of the disease.Citation79 Further investigation into the application of tele-health in multidisciplinary rehabilitation and palliative care services for ALS patients and their families is required.

Timing of decisions for symptom management and end-of-life care

Patients (and families) are often required to make decisions for symptom management and quality of life as the disease progresses.Citation83–Citation85 Decisions are made with multiple health professionals and require cross-sector coordination. Decisions for life-extending or symptomatic measures (eg, gastrostomy, invasive ventilation and non-invasive ventilation), as well as end-of-life care, are complex.Citation16,Citation17 Successful outcomes can depend upon the timing of interventions. Patients are encouraged to consider their options and make choices about care in a timeframe that enables successful outcomes for both patients and their family caregivers. The consequences of avoiding decision making, for example, for nutrition/hydration or respiratory distress, can impact the patient’s health and quality of life. However, some patients may also feel conflicted by having to make decisions about care.Citation86,Citation87 Patients may not feel ready for procedures or equipment that signal further deterioration in their condition and that which would increase their dependence on family members. Life-extending measures may also conflict with patients’ and family caregivers’ long-held values pertaining to end-of-life care.

The ALS MDC can offer patients and their family caregivers a supportive setting when discussing treatment decisions.Citation86,Citation87 A model to guide decision making in ALS that incorporates patients and their carers in the decision-making processes of care has been developed from the MDC setting.Citation22,Citation38 This model facilitates shared decision making with patients and their carers and situates patients and their carers within the multidisciplinary network of care. Allowing sufficient time and space for patients and their carers to digest information about care, deliberate on the options available to them, and make decisions about how they would like to engage with multidisciplinary care are key components of inclusive decision making in multidisciplinary ALS care.Citation22 The ALS MDC setting can be a suitable forum for a multidisciplinary team to collectively engage with patients and their family in shared decision making pertaining to symptom management and quality-of-life choices.Citation87

Developments in multidisciplinary ALS care

The evolving multidisciplinary ALS care team

As models of care evolve to keep pace with the new understanding of this complex disorder, the multidisciplinary ALS care team has expanded accordingly.Citation10,Citation16,Citation17,Citation42,Citation88 Recent additions to the multidisciplinary ALS care team have included neuropsychologists, genetic counselors, and case managers. A frontotemporal syndrome occurs in a substantial proportion of ALS patients, a subgroup of whom present with frontotemporal dementia.Citation89 Expert consensus is that care provision in ALS should include interventions directed toward the management of cognitive and behavioral impairment in ALS, including educational and support services for family carers on how best to support and care for ALS patients who have cognitive or behavioral impairment.Citation10,Citation16 In this context, neuropsychologists make an important contribution to the care of ALS patients and their caregivers.

The identification of multiple novel genes in ALS and the newly recognized link between ALS and frontotemporal dementia have resulted in the need to incorporate genetic counseling into multidisciplinary ALS care.Citation16,Citation90,Citation91. However, ALS patients have reported difficulty accessing genetic testing.Citation92 Indeed, studies have yet to estimate the proportion of the ALS population that engage with genetic testing and genetic counseling. Genetic counseling in ALS may pose significant challenges to patients, family, and health professionals, in the context of the ethical, legal, and psychological dimension surrounding disclosure, and the impact the disclosure can have on the wider family.Citation91 Nonetheless, ALS patients have reported high levels of interest in genetic testing.Citation92

The role of case management in ALS, in which designated professionals work collaboratively with patients and their families, guiding and supporting them through the different phases of care, has been examined.Citation42,Citation88 Initially, a Dutch randomized control study on case management in ALSCitation88 showed that case management conferred no benefit to patient health-related quality of life or to caregiver strain when compared to normal care. However, a qualitative investigation of patients’ and their caregivers’ perceptions of the same serviceCitation42 identified that ALS patients and their families were receptive to case management and that they valued the additional emotional support available to them from a case manager. Patients’ and caregivers’ own coping styles and their satisfaction or dissatisfaction with usual care influenced how receptive they were to case management.Citation42

Benefits and challenges to health professionals in delivering coordinated and interprofessional ALS care

Alongside the benefits that patients and their family encounter in multidisciplinary ALS care are advantages to health care professionals who work within the MDCs. Health professionals gain experience and expertise in ALS care,Citation93 learning from patients and family caregivers when supported in a clinical environment dedicated to ALS care. Although patient satisfaction with MDC services is in general high,Citation62 the provision of multidisciplinary-based care to people with ALS and their families can have a significant impact on health care professionals who render and coordinate the care. Health professionals in ALS care can experience varying degrees of stress related to their clinical work,Citation94 and the emotional burden encountered by health care professionals caring for people with ALS can be severe.Citation55 Feelings of stress and anxiety can arise for physicians while delivering the diagnosis and prognosis,Citation72 whereas withdrawal of treatments can pose ethical and psychological dilemmas for health care professionals who provide end-of-life care.Citation95,Citation96 In an Australian-based study,Citation72 70% of neurologists surveyed found communicating the diagnosis of ALS “very to somewhat difficult,” whereas 43% of them found responding to patients’ and family members’ reaction to the disclosure “very to somewhat difficult.” Sixty-five percent of neurologists experienced “high to moderate” stress and anxiety during the disclosure. Physicians reported the challenges surrounding the need to be honest without taking away hope, dealing with the patient’s emotional reaction to the diagnosis, and judging the optimal amount of time to deliver the diagnosis. The reasons for experiencing these difficulties included the lack of effective treatments in ALS, fear of causing distress to patients, and fear of not having all the answers for patients.

Support and education systems need to be developed that help health care professionals to manage the emotional and moral distress that they encounter in ALS practice.Citation97 Connolly et alCitation55 called for a recognition of the emotional burden that health care professionals encounter when caring for people with ALS, “with structures and procedures developed to address compassion, fatigue, and the moral and ethical challenges related to providing end-of-life care” (p. 435). Support from health care organizations is required to ensure that health professionals in multidisciplinary ALS care are financially and emotionally supported in their role as service providers.Citation87

Conclusion

Specialized multidisciplinary care is more than a means of delivering appropriate symptom management to ALS patients. This review has identified that coordinated and interprofessional care that meets the expectations of ALS patients and their families is a combination of multiple facets of care. These include care underpinned by an increasing evidence base; service providers applying a patient- if not family-centric approach to care; strong inter-service communication; and an interprofessional team resourced and funded to provide expert care to patients and their family caregivers.

MDC-based care in ALS offers benefits and challenges to patients, carers, and health professionals. Importantly, the evidence in ALS care has been fueled by research undertaken and coordinated by MDCs.Citation23,Citation29,Citation32 The links between interprofessional practice and clinical research are strengthened when frontline clinicians, patients, and carers are able to contribute to our understanding of how multidisciplinary ALS care improves patient care and quality of life.

Although MDCs offer an optimal model of coordinated interprofessional care, the transition of care between care settings remains a concern. Strategies toward standardizing care delivery for patients and carers may help to reduce the wide-ranging experiences from the very good to the not so good. The development of best practice guidelines and of protocols to improve inter-service communication skills among health care professionals may alleviate the emotional burden of service providers and the distress that patients and their family encounter when confronted with poorly coordinated care.

Finally, patients’ attendance rates at specialized ALS MDCs show that a significant portion of ALS patients are not able, or choose not, to access MDC care. Stronger links between specialized ALS MDC services, general neurology, and primary care services could improve the quality of care for patients being managed in their own community and increase the expertise of practitioners outside the current MDC network. An improved understanding among the wider health care community of how MDC teams deliver care will assist the development of clinical pathways that connect MDC and non-MDC services. A network that is accessible to all clinical services caring for ALS patients will improve patient care, service transition, and health care professionals’ understanding of ALS.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- KiernanMCVucicSCheahBCAmyotrophic lateral sclerosisLancet2011377976994295521296405

- MitchellJDBorasioGDAmyotrophic lateral sclerosisLancet200736995782031204117574095

- LilloPGarcinBHornbergerMBakTHHodgesJRNeurobehavioral features in frontotemporal dementia with amyotrophic lateral sclerosisArch Neurol201067782683020625088

- CagaJRamseyEHogdenAMioshiEKiernanMCA longer diagnostic interval is a risk for depression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosisPalliat Support Care20151341019102425137152

- LilloPMioshiEZoingMCKiernanMCHodgesJRHow common are behavioural changes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis?Amyotroph Lateral Scler2011121455120849323

- LilloPSavageSMioshiEKiernanMCHodgesJRAmyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia: a behavioural and cognitive continuumAmyotroph Lateral Scler201213110210922214356

- LuleDHackerSLudolphABirbaumerNKublerADepression and quality of life in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosisDtsch Arztebl Int20081052339740319626161

- ChenDGuoXZhengZDepression and anxiety in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: correlations between the distress of patients and caregiversMuscle Nerve201551335335724976369

- NgLKhanFMathersSMultidisciplinary care for adults with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or motor neuron diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20094CD00742519821416

- MillerRGJacksonCEKasarskisEJPractice parameter update: the care of the patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: multidisciplinary care, symptom management, and cognitive/behavioral impairment (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of NeurologyNeurology200973151227123319822873

- JacksonCEMcVeyALRudnickiSDimachkieMMBarohnRJSymptom management and end-of-life care in amyotrophic lateral sclerosisNeurol Clin201533488990826515628

- RiemenschneiderKAForshewDAMillerRGMultidisciplinary clinics: optimizing treatment for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosisNeurodegen Dis Manage201332157167

- AounSMBreenLJHowtingDReceiving the news of a diagnosis of motor neuron disease: what does it take to make it better?Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener2016173–416817826609553

- AounSMConnorsSLPriddisLBreenLJColyerSMotor neurone disease family carers’ experiences of caring, palliative care and bereavement: an exploratory qualitative studyPalliat Med201226684285021775409

- HardimanOMultidisciplinary care in ALS: measuring the immeasurableAmyotroph Lateral Scler and Frontotemporal Degener201516Supp 1S5

- AndersenPMAbrahamsSBorasioGDEFNS guidelines on the clinical management of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (MALS) – revised report of an EFNS task forceEur J Neurol201219336037521914052

- MillerRGJacksonCEKasarskisEJPractice parameter update: the care of the patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: drug, nutritional, and respiratory therapies (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of NeurologyNeurology200973151218122619822872

- CorrBFrostETraynorBJHardimanOService provision for patients with ALS/MND: a cost-effective multidisciplinary approachJ Neurol Sci1998160Suppl 1S141S1459851665

- van TeijlingenERFriendEKamalADService use and needs of people with motor neurone disease and their carers in ScotlandHealth Soc Care Community20019639740311846819

- HarrisRAbramsWThe International Alliances of ALS/MND AssociationsAmyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord20034421421614753654

- MayadevASWeissMDDistadBJKrivickasLSCarterGTThe amyotrophic lateral sclerosis center: a model of multidisciplinary managementPhys Med Rehabil Clin N Am2008193619631xi18625420

- HogdenAGreenfieldDNugusPKiernanMCDevelopment of a model to guide decision making in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis multidisciplinary careHealth Expect20151851769178224372800

- GuellMRAntonARojas-GarciaRPuyCPradasJen representacion de todo el grupo iComprehensive care of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients: a care modelArch Bronconeumol2013491252953323540596

- HardimanOTraynorBJCorrBFrostEModels of care for motor neuron disease: setting standardsAmyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord20023418218512710506

- ICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence)Motor neurone disease: assessment and management Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng42. Published February 2016Accessed January 27, 2017

- MarinBBeghiEVialCEvaluation of the application of the European guidelines for the diagnosis and clinical care of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) patients in six French ALS centresEur J Neurol201623478779526833536

- FullamTStephensHEFelgoiseSHBlessingerJKWalshSSimmonsZCompliance with recommendations made in a multidisciplinary ALS clinicAmyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener2015171–2303726513201

- BorasioGDShawPJHardimanOLudolphACSales LuisMLSilaniVEuropean ALS Study GroupStandards of palliative care for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: results of a European surveyAmyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord20012315916411771773

- Van den BergJPKalmijnSLindemanEMultidisciplinary ALS care improves quality of life in patients with ALSNeurology20056581264126716247055

- ChioABottacchiEBuffaCMutaniRMoraGPARALSPositive effects of tertiary centres for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis on outcome and use of hospital facilitiesJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry200677894895016614011

- TraynorBJAlexanderMCorrBFrostEHardimanOEffect of a multidisciplinary amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) clinic on ALS survival: a population based study, 1996–2000J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry20037491258126112933930

- RooneyJByrneSHeverinMA multidisciplinary clinic approach improves survival in ALS: a comparative study of ALS in Ireland and Northern IrelandJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry201586549650125550416

- ZoccolellaSBeghiEPalaganoGALS multidisciplinary clinic and survival. Results from a population-based study in Southern ItalyJ Neurol200725481107111217431705

- DharmadasaTMatamalaJMKiernanMCTreatment approaches in motor neurone diseaseCurr Opin Neurol201629558159127454577

- BedePHardimanOO’BrannagainDAn integrated framework of early intervention palliative care in motor neurone disease as a model for progressive neurodegenerative diseasesPoster presented at: 7th European ALS CongressMay 22–24, 2009Turin, Italy

- HardimanOMultidisciplinary care in motor neurone diseaseKiernanMCThe Motor Neurone Disease HandbookSydney, AustraliaMJA Books2007164174

- CollinsAMeasuring What Really Matters. Towards a Coherent Measurement System to Support Person-Centred CareLondonThe Health Foundation2014

- HogdenAOptimizing patient autonomy in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: inclusive decision-making in multidisciplinary careNeurodegener Dis Manag2014411324640972

- FoleyGTimonenVHardimanOPatients’ perceptions of services and preferences for care in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. A reviewAmyotroph Lateral Scler2012131112421879834

- AounSMBentleyBFunkLToyeCGrandeGStajduharKJA 10-year literature review of family caregiving for motor neurone disease: moving from caregiver burden studies to palliative care interventionsPalliat Med201327543744622907948

- CreemersHde MoreeSVeldinkJHNolletFvan den BergLHBeelenAFactors related to caregiver strain in ALS: a longitudinal studyJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry201687777578126341327

- BakkerMCreemersHSchipperKNeed and value of case management in multidisciplinary ALS care: a qualitative study on the perspectives of patients, spousal caregivers and professionalsAmyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener2015163–418018625611162

- EwingGAustinLDiffinJGrandeGDeveloping a person-centred approach to carer assessment and supportBr J Community Nurs2015201258058426636891

- AounSMBreenLJOliverDFamily carers’ experiences of receiving the news of a diagnosis of motor neurone disease: a national surveyJ Neurol Sci201737214415128017202

- AounSDeasKToyeCEwingGGrandeGStajduharKSupporting family caregivers to identify their own needs in end-of-life care: qualitative findings from a stepped wedge cluster trialPalliat Med201529650851725645667

- HogdenAGreenfieldDNugusPKiernanMCWhat are the roles of carers in decision-making for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis multidisciplinary care?Patient Prefer Adherence2013717118123467637

- ZoingMMotor neurone disease: a nurse’s perspectiveKiernanMCThe Motor Neurone Disease HandbookSydney, AustraliaMJA Books2007175185

- PaganoniSKaramCJoyceNBedlackRCarterGTComprehensive rehabilitative care across the spectrum of amyotrophic lateral sclerosisNeuroRehabilitation2015371536826409693

- MajmudarSWuJPaganoniSRehabilitation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: why it mattersMuscle Nerve201450141324510737

- OliverDAounSWhat palliative care can do for motor neurone disease and their familiesEur J Palliat Care2013206286289

- BedePOliverDStodartJPalliative care in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a review of current international guidelines and initiativesJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry201182441341821297150

- OliverDBorasioGDJohnstonWPalliative Care in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis From Diagnosis to Bereavement3rd edOxfordOxford University Press2014

- OliverDWatsonSMultidisciplinary careOliverDEnd of Life Care in Neurological DiseaseLondonSpringer2012113132

- OliverDJBorasioGDCaraceniAA consensus review on the development of palliative care for patients with chronic and progressive neurological diseaseEur J Neurol2016231303826423203

- ConnollySGalvinMHardimanOEnd-of-life management in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosisLancet Neurol201514443544225728958

- van der SteenIvan den BergJPBuskensELindemanEvan den BergLHThe costs of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, according to type of careAmyotroph Lateral Scler2009101273418608087

- ConnollySHeslinCMaysICorrBNormandCHardimanOHealth and social care costs of managing amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS): an Irish perspectiveAmyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener2015161–2586225285902

- Lopez-BastidaJPerestelo-PerezLMonton-AlvarezFSerrano-AguilarPAlfonso-SanchezJLSocial economic costs and health-related quality of life in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in SpainAmyotroph Lateral Scler200910423724318821088

- Deloitte Access Economics 2015, Economic analysis of motor neurone disease in Australia, report for Motor Neurone Disease Australia, Deloitte Access Economics, Canberra, November Available from http://www.mndaust.asn.au/Influencing-policy/Economic-analysis-of-MND-(1)/Economic-analysis-of-MND-in-Australia.aspxAccessed March 30, 2017

- OhJAnJWOhSISocioeconomic costs of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis according to staging systemAmyotroph Lateral Scler Fron-totemporal Degener2015163–4202208

- GladmanMDharamshiCZinmanLEconomic burden of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a Canadian study of out-of-pocket expensesAmyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener2014155–642643225025935

- BoylanKLevineTLomen-HoerthCALS Center Cost Evaluation W/Standards & Satisfaction (Access) ConsortiumProspective study of cost of care at multidisciplinary ALS centers adhering to American Academy of Neurology (AAN) ALS practice parametersAmyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener2015171–211912726462131

- GalvinMMaddenCMaguireSPatient journey to a specialist amyotrophic lateral sclerosis multidisciplinary clinic: an exploratory studyBMC Health Serv Res20151557126700026

- TurnerMRScaberJGoodfellowJALordMEMarsdenRTalbotKThe diagnostic pathway and prognosis in bulbar-onset amyotrophic lateral sclerosisJ Neurol Sci20102941–2818520452624

- GladmanMZinmanLThe economic impact of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a systematic reviewExpert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res201515343945025924979

- PaganoniSMacklinEALeeADiagnostic timelines and delays in diagnosing amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener2014155–645345624981792

- HousehamESwashMDiagnostic delay in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: what scope for improvement?J Neurol Sci20001801–2768111090869

- O’BrienMRWhiteheadBJackBAMitchellJDFrom symptom onset to a diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/motor neuron disease (ALS/MND): experiences of people with ALS/MND and family carers – a qualitative studyAmyotroph Lateral Scler20111229710421208037

- MitchellJDCallagherPGardhamJTimelines in the diagnostic evaluation of people with suspected amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)/motor neuron disease (MND) – a 20-year review: can we do better?Amyotroph Lateral Scler201011653754120565332

- CallagherPMitchellDBennettWAddison-JonesREvaluating a fast-track service for diagnosing MND/ALS against traditional pathwaysBr J Neurosci Nurs200957322325

- Motor Neurone Disease Association webpage on the InternetRed Flag diagnosis tool2014 Available from: http://www.mndassociation.org/forprofessionals/information-for-gps/diagnosis-of-mnd/red-flag-diagnosis-tool/Accessed January 5, 2017

- AounSMBreenLJEdisRBreaking the news of a diagnosis of motor neurone disease: a national survey of neurologists’ perspectivesJ Neurol Sci201636736837427423623

- O’BrienMWhiteheadBJackBMitchellJDMultidisciplinary team working in motor neurone disease: patient and family carer viewsBr J Neurosci Nurs201174580585

- ALS Centrum Nederland [webpage on the Internet]Over het ALS Centrum [updated 2017] Available from: http://www.als-centrum.nl/over-het-als-centrumAccessed February 17, 2017

- StephensHEFelgoiseSYoungJSimmonsZMultidisciplinary ALS clinics in the USA: a comparison of those who attend and those who do notAmyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener2015163–419620125602166

- StephensHEYoungJFelgoiseSHSimmonsZA qualitative study of multidisciplinary ALS clinic use in the United StatesAmyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener2015171–2556126508132

- HobsonEVBairdWOCooperCLMawsonSShawPJMcDermottCJUsing technology to improve access to specialist care in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a systematic reviewAmyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener2016175–631332427027466

- HendersonRDHutchinsonNDouglasJADouglasCTelehealth for motor neurone diseaseMed J Aust2014201131

- VitaccaMCominiLAssoniGTele-assistance in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: long term activity and costsDisabil Rehabil Assist Technol20127649450022309823

- Nijeweme-d’HollosyWOJanssenEPHuis in ’t VeldRMSpoelstraJVollenbroek-HuttenMMHermensHJTele-treatment of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)J Telemed Telecare200612Suppl 1S31S34

- ZamarronCMoreteEGonzalezFTelemedicine system for the care of patients with neuromuscular disease and chronic respiratory failureArch Med Sci20141051047105125395959

- PintoAAlmeidaJPPintoSPereiraJOliveiraAGde CarvalhoMHome telemonitoring of non-invasive ventilation decreases healthcare utilisation in a prospective controlled trial of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosisJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry201081111238124220826878

- HogdenAGreenfieldDCagaJCaiXDevelopment of patient decision support tools for motor neuron disease using stakeholder consultation: a study protocolBMJ Open201664e010532

- OliverDCampbellCSykesNTallonCEdwardsADecision-making for gastrostomy and ventilatory support for people with motor neurone disease: variations across UK hospicesJ Palliat Care201127319820121957796

- OliverDJTurnerMRSome difficult decisions in ALS/MNDAmyotroph Lateral Scler201011433934320550485

- HogdenAGreenfieldDNugusPKiernanMCWhat influences patient decision-making in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis multidisciplinary care? A study of patient perspectivesPatient Prefer Adherence2012682983823226006

- HogdenAGreenfieldDNugusPKiernanMCEngaging in patient decision-making in multidisciplinary care for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: the views of health professionalsPatient Prefer Adherence2012669170123055703

- CreemersHVeldinkJHGrupstraHNolletFBeelenAvan den BergLHCluster RCT of case management on patients’ quality of life and caregiver strain in ALSNeurology2014821233124285618

- GoldsteinLHAbrahamsSChanges in cognition and behaviour in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: nature of impairment and implications for assessmentLancet Neurol201312436838023518330

- RoggenbuckJQuickAKolbSJGenetic testing and genetic counseling for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: an update for cliniciansGenet Med201619326727427537704

- ChioABattistiniSCalvoAGenetic counselling in ALS: facts, uncertainties and clinical suggestionsJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry201485547848523833266

- WagnerKNNagarajaHAllainDCQuickAKolbSRoggenbuckJPatients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis have high interest in and limited access to genetic testingJ Genet Couns Epub20161020

- Aho-OzhanHEBohmSKellerJExperience matters: neurologists’ perspectives on ALS patients’ well-beingJ Neurol Epub2017124

- BrombergMBSchenkenbergTBrownellAAA survey of stress among amyotrophic lateral sclerosis care providersAmyotroph Lateral Scler201112316216721545236

- FaullCRowe HaynesCOliverDIssues for palliative medicine doctors surrounding the withdrawal of non-invasive ventilation at the request of a patient with motor neurone disease: a scoping studyBMJ Support Palliat Care2014414349

- PhelpsKRegenEOliverDMcDermottCFaullCWithdrawal of ventilation at the patient’s request in MND: a retrospective exploration of the ethical and legal issues that have arisen for doctors in the UKBMJ Support Palliat Care Epub2015911

- SchellenbergKLSchofieldSJFangSJohnstonWSBreaking bad news in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: the need for medical educationAmyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener2014151–2475424245652

- MaddocksIBrewBWaddyHWilliamsIPalliative NeurologyCambridgeCambridge University Press2005