Abstract

Despite enormous progress in the field of pain management over the recent years, pain continues to be a highly prevalent medical condition worldwide. In the developing countries, pain is often an undertreated and neglected aspect of treatment. Awareness issues and several misconceptions associated with the use of analgesics, fear of adverse events – particularly with opioids and surgical methods of analgesia – are major factors contributing to suboptimal treatment of pain. Untreated pain, as a consequence, is associated with disability, loss of income, unemployment and considerable mortality; besides contributing majorly to the economic burden on the society and the health care system in general. Available guidelines suggest that a strategic treatment approach may be helpful for physicians in managing pain in real-world settings. The aim of this manuscript is to propose treatment recommendations for the management of different types of pain, based on the available evidence. Evidence search was performed by using MEDLINE (by PubMed) and Cochrane databases. The types of articles included in this review were based on randomized control studies, case–control or cohort studies, prospective and retrospective studies, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, clinical practice guidelines and evidence-based consensus recommendations. Articles were reviewed by a multidisciplinary expert panel and recommendations were developed. A stepwise treatment algorithm-based approach based on a careful diagnosis and evaluation of the underlying disease, associated comorbidities and type/duration of pain is proposed to assist general practitioners, physicians and pain specialists in clinical decision making.

Introduction

Pain, as defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) is “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage”.Citation1 Pain can be experienced as an acute, chronic or intermittent sensation, or as a combination of the three, and is reported to be the common reason for medical visits. However, since pain has always been regarded as a symptom, not a disease state,Citation2 there has been an enormous gap between prevalence and treatment, and it remains largely undertreated.Citation3,Citation4 Acute pain, the most commonly experienced type of pain, may be a result of injuries, acute illnesses, surgeries or labor.Citation5 The overall prevalence of acute pain in hospital and ambulatory settings is reported to range between 30% and 80%.Citation6–Citation8 In addition to discomfort, uncontrolled acute pain translates to chronic pain, which may lead to delayed healing, prolonged hospitalization and increased morbidity.Citation9 Globally, approximately 20% of adults suffer from pain, of which, 10% report persistent pain.Citation10 Contrary to acute pain, chronic pain is seldom considered an individual entity, the focus majorly being on symptom relief. Chronic pain is generally associated with chronic illnesses such as neuropathy, cancer or human immunodeficiency virus infection–acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV-AIDS), and it is difficult to predict the nature and severity of pain.Citation11 Several studies report a significantly high prevalence of chronic pain with certain neuropathic characteristics (6%–10%), which is of higher severity and longer duration.Citation12–Citation14 Untreated chronic pain significantly affects the quality of life (QoL) of the patients,Citation15 is associated with considerable mortality,Citation16 and can be a major cause of absenteeism from work or reduced work performance as well as loss of productivity.Citation17

In developed countries too, pain is a commonly reported medical problem and comes with immense personal costs and a huge societal health care burden;Citation18,Citation19 the cost of chronic pain in the US has been estimated at $560–$635 billion.Citation19 It is, therefore, not surprising to note an uncharacteristically high prevalence of pain in a developing economy like India, which is already struggling with a growing disease burden and lack of quality health care resources.Citation20 According to the Global Burden of Diseases (GBD) survey, low-back pain (LBP) and migraine were amongst the top five medical conditions resulting in years lived with disability in the Indian population in 2013.Citation21 In India, around 100,000 patients with cancer or HIV-AIDS die every year due to inadequate pain treatment.Citation22 A survey of chronic pain conducted across eight major cities in India highlighted a high point prevalence (13%) of chronic pain, with 30% of the patients without treatment and 56% reporting unsatisfactory treatment.Citation23

Currently, there is a need to develop treatment recommendations based on available evidence to guide Indian physicians in the management of pain.

Unmet needs of India

According to a survey by the World Health Organization (WHO), the incidence of chronic pain was demonstrated to range between 5% and 33% in 15 centers across Asia, Africa, Europe and the USA.Citation10 India has a high burden of chronic diseases and injuries, which are the leading causes of disability and mortality and have pain as comorbidity.Citation24,Citation25 Globally, pain prevalence in the elderly population is highCitation26 and is further expected to rise,Citation27,Citation28 owing to the presence of multiple comorbiditiesCitation29 and barriers related to communication and cognition.Citation30 With a considerable increase in life expectancy in the past decade, India has witnessed an unprecedented rise in the ailing population, who are struggling to get adequate treatment for pain.Citation31,Citation32 Furthermore, there are some additional challenges, such as lack of adequate health care facilities, poverty, inadequate health care expenditure and lack of awareness among health care practitioners and patients.Citation33 Health care centers in India are often not well equipped to provide adequate treatment for pain, with physicians relying mostly on over-the-counter analgesics.Citation34,Citation35 This generalized approach seldom works in most complex pain disorders, which require a detailed diagnosis and thoughtful, planned management.Citation36 Another concern stemming from lack of awareness is the use of irrational and inappropriate multidrug prescriptions in India. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the second most common components of prescriptions in India.Citation37–Citation39 Rampant polypharmacy, coupled with lack of awareness, has had a huge impact on analgesic efficacy and presents tolerability issues.Citation40 Several misconceptions regarding use of analgesics and fear of adverse events associated with the use of opioids or surgical methods of analgesia result in suboptimal treatment of pain.Citation41,Citation42 These inadequacies might be overcome by the amalgamation of expert opinions and available evidence to form standardized treatment guidelines for pain therapy. Hence, an expert panel was convened to delve on these lacunae and frame an appropriate treatment paradigm for pain management. The objective of this publication is to summarize the evidence-based consensus recommendations of this expert panel for the pharmacological management of pain in India.

Methodology

Literature search of the current evidence was performed using the MEDLINE (by PubMed) and Cochrane databases. The articles included randomized control studies, case–control or cohort studies, prospective and retrospective studies, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, clinical practice guidelines and evidence-based consensus recommendations. Evidence grading was performed as per the following criteria used by the National Guidelines Clearinghouse:Citation43

Level 1: evidence from randomized control studies, systematic reviews and meta-analyses

Level 2: evidence from nonrandomized, prospective or retrospective studies

Level 3: evidence from comparative, case–control and descriptive studies

Level 4: expert committee reports or clinical opinions of respected authorities

A multidisciplinary expert panel, composed of pain specialists, orthopedic surgeons, gastroenterologists, cardiologists, neurologists and nephrologists, with clinical and research expertise in the diagnosis and treatment of pain was convened, and recommendations were formulated based on expert opinions and available evidence. Based on the level of evidence, recommendations were graded as follows:

Grade A: based on evidence Level 1

Grade B: based on evidence Level 2 or extrapolated from Level 1

Grade C: based on evidence Level 3 or extrapolated from Level 1 and 2

Grade D: based on evidence Level 4 or extrapolated from Levels 1–3

Recommendation statements were developed, circulated among panel members and modified based on their feedback until unified consensus was achieved.

Types of pain

Several methods of classification of pain have been developed to assist the physician in the appropriate diagnosis and treatment of pain in routine clinical practice. Pain can be classified into different types on the basis of duration or intensity, pathological mechanism and anatomic location ().

Table 1 Different types of pain

Based on underlying pathophysiology

Nociceptive pain

Nociceptive pain is elicited through A, δ and C nociceptive receptors present in peripheral tissues, which are activated by chemical, mechanical or thermal stimuli.Citation44 These receptors play an important role in the regulation of natural defense mechanisms and elicit pain as a response to potential tissue damage. A number of chemical substances aggravate the nociceptive response to pain; the most common ones are bradykinin, histamine, serotonin and prostaglandins (cyclooxygenase [COX] 1 and 2).

Neuropathic pain

Neuropathic pain primarily refers to pain initiated or caused by a primary lesion or damage to the central nervous system and includes disorders such as peripheral neuropathy, diabetic neuropathy, postherpetic neuralgia, trigeminal neuralgia, causalgia and certain types of cancer pain.Citation45,Citation46 The pathways attributed to the generation of neuropathic pain involve abnormal excitability of afferent neurons, central sensitization following peripheral activation of neurons, loss of primary afferent response and activation of proinflammatory cytokines.Citation47,Citation48 Each of these factors may correspond to a particular mechanistic pathway, causing differences in the pattern and intensity of the somatosensory response.Citation49,Citation50

Mixed pain

In certain cases, pain may result from a combination of nociceptive and neuropathic processes.Citation51 This type of pain is considered as the mixed type and is most frequently experienced by patients with cancer and those with some complex neuropathies.Citation52–Citation54

Based on duration

Acute pain

Acute pain is caused due to an existing disease or injury, usually lasting for hours, days or months or until the disease or injury is healed.Citation55 This type of pain has a certain identifiable biological origin and is predictable in nature.Citation56 Acute pain is a part of the normal biological defense against a potential threat or injury and is accompanied by protective reflexes.Citation57 The sources of acute pain could be an acute illness (eg, appendicitis), perioperative (pain due to existing disease and surgical procedure), major trauma (vehicle accident), burns or due to childbirth.

Chronic pain

Chronic pain persists even after the healing of the disease or injury and may be physically and emotionally distressing. Often, there is no single biological point of origin for this pain, resulting in a complex pathophysiology that necessitates the use of multiple therapeutic interventional strategies for alleviation.Citation58 This type of pain may be a result of an existing chronic disorder (examples are cancer or noncancer pain such as HIV-AIDS, rheumatoid arthritis and LBP) or may have no known cause (idiopathic pain). Moreover, some secondary causes may include increased sensitivity to external stimuli (hyperalgesia) or pain due to innocuous stimuli (allodynia).Citation59

Breakthrough pain

Breakthrough pain is defined as transient flare-ups of severe and uncontrolled pain, in adequately controlled pain settings.Citation60 These episodic exacerbations of pain are characteristically observed in patients with cancer and last usually from a few seconds to hours. Breakthrough pain may be idiopathic (without known cause), incidental and associated with a precipitating factor (eg, movement), or may be experienced in the interim between two doses.Citation61

Based on etiology

Cancer pain

Pain is the most common symptom experienced by patients with cancer. The origin of cancer pain may be nociceptive (somatic or visceral) when there are changes in the underlying tissue pathology and neuropathic, when there is an involvement of neuronal damage. The severity of cancer pain increases as the disease progresses, with patients in the metastatic stage reporting the most severe pain.Citation62 Cancer pain may be felt at the site of tumor or may be referred to a secondary region of the body.Citation63 Breakthrough pain is another feature of cancer pain, which may be a consequence of repeated nociceptive sprouting or synaptic changes at the spinal dorsal horn (DH).Citation64 Optimization of opioid therapy may be useful in preventing episodic exacerbations at the end of dose.Citation65

Noncancer pain

Chronic pain due to nonmalignant causes is referred to as chronic noncancer pain (CNCP). Unlike cancer pain, CNCP may present no identifiable underlying pathology, may show increased heterogeneity and may be more challenging to treat.Citation66 CNCP may be classified further as neuropathic pain (peripheral and central), inflammatory pain (infectious, arthritic and postoperative pain), muscle pain (myofascial pain syndrome) and mechanical pain (LBP, neck-and-shoulder pain). Various practice guidelines advocate the use of opioids as first-, second- or third-line therapy in CNCP, following failure of nonopioid analgesics.Citation67,Citation68

Based on anatomic location

For this purpose, anatomic location refers to a region or site where the actual pain may be localized, rather than the location of the body system where the pain originated.Citation69 As per the IASP, pain is anatomically classified, regardless of origin, as localized to head, face and mouth pain; cervical pain; upper shoulder and upper limb pain; thoracic pain; abdominal pain; LBP, lumbar spine and coccyx pain; lower limb pain; pelvic pain; as well as anal, perineal and genital pain.Citation70 Although this categorization helps in differential diagnosis, it cannot be used as a basis for therapeutic management.Citation71

Somatic pain

Somatic pain is a sharp, well-localized pain emanating from the skin due to superficial damage and activation of peripheral nociceptors on the skin or mucous membranes.Citation72 Alternatively, the pain may be deep and central in origin, originating from muscles, tendons or joints. Examples are LBP, neck pain, musculoskeletal pain and pain due to burns, injuries or wounds.Citation73

Visceral pain

Visceral pain is deep, poorly localized pain resulting from pressure or damage to internal organs; it may be accompanied by low blood pressure, nausea or sweating as a response to stimulation of nerve endings that are at the site of pain and that relay signals to the CNS. Examples of visceral pain are gall/kidney stones, gastric ulcers or intestinal spasms.Citation74,Citation75

Referred pain

Pain that is felt at a site away from the site of injury is called referred pain. The origin of referred pain may be somatic (involving muscles or joints) or visceral (involving visceral organs).Citation76 Several mechanistic theories have been suggested to be involved in the cause of referred pain. Referred visceral pain may be attributed to the hyperexcitability of adjacent spinal neurons in response to nociceptive stimuli or a possible activation of the peripheral reflex arc via the efferent pathway.Citation77 Examples of referred pain are myocardial pain and anginal pain.

International Classification of Diseases, Eleventh Revision (ICD-11) criteria for classification of chronic pain

Although several methods of classification are available for the categorization of pain, there is a lack of accurate and consistent terminology for the coding of chronic pain in compliance with the ICD system used by the WHO. Responding to this, the IASP developed a system of classification of chronic pain based on the ICD criteria, which takes into consideration the etiology, location and pathophysiology of pain for better categorization of the disease. Categorization is based on multiple parenting, wherein each diagnosis falls under one primary category/parent but corresponds to more-than-one secondary categories.Citation78 According to this classification, chronic pain may be categorized as primary pain, cancer pain, posttraumatic or postsurgical pain, neuropathic pain, headache and orofacial pain, and musculoskeletal and visceral pain.

Pathophysiology of pain

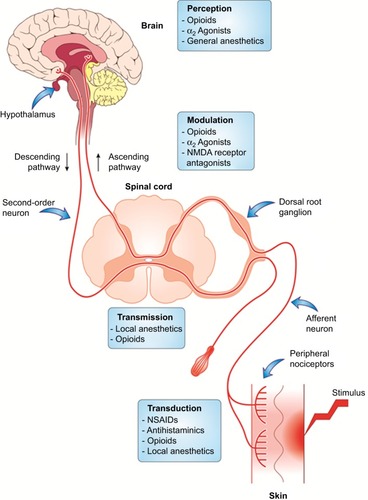

Regardless of its categorization, pain cannot be distinctly attributed to any isolated pathological event. Pain experience is a complex process that involves the activation of multiple neuronal signaling pathways within the peripheral nervous system (PNS) and central nervous system (CNS).Citation73,Citation79,Citation80 The subjective experience of pain may be summarized as a four-stage process - transduction, transmission, modulation and perception.Citation81 In stage 1 (transduction), nociceptive stimuli of tissue-damaging potential (including mechanical, chemical and thermal stimuli) are converted by the sensory cells into action potentials. Stage 2 (transmission) involves the conduction of these action potentials along afferent neurons to the DH of the spinal cord. In stage 3 (modulation), coding of nociceptive information occurs at the level of spinal DH. Modulation at the DH can be excitatory or inhibitory, thereby increasing or decreasing the resulting pain. Stage 4 involves generation of autonomic, affective, cognitive and behavioral responses to the painful stimulus, leading to pain perception.

Sensitization

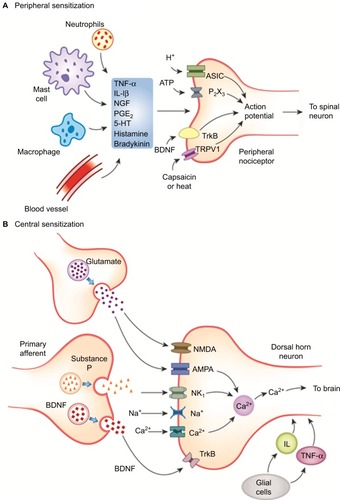

Peripheral sensitization

Peripheral sensitization is characterized by abnormal sensitivity of afferent nociceptors to noxious stimuli. Nociceptors on the skin and deeper tissues sometimes become extremely sensitive to intense noxious stimuli in the presence of inflammation. This further lowers the threshold of nociceptor activation to normally innocuous or less-painful stimuli, accompanied by an increase in the degree or magnitude of response. Additionally, extreme sensitization may lead to the activation of sleeping or silent nociceptors, which upon excitation amplify the pain response manifold. Drugs acting at the peripheral nociceptor level are NSAIDs, opioids, cannabinoids and transient-receptor potential vanilloid (TRPV1) receptor antagonists.

Central sensitization

Afferent pain signals from the peripheral nociceptors to the spinal neurons may sometimes activate low-threshold mechanoceptors at the DH, thus amplifying the central neuronal response to noxious stimuli.Citation82 This phenomenon of altered sensitivity of neuronal cells at the level of the second-order neuron is known as central sensitization. Central sensitization is implicated in the transition of acute pain to chronic degenerative pain. As observed with peripheral sensitization, primary hyperalgesia is the first manifestation of altered threshold at the central neuronal level.Citation82 Under pathological conditions, receptors that are normally associated with sensory response to stimuli such as touch may acquire the ability to produce pain, resulting in secondary hyperalgesia, an important aspect of central sensitization.Citation64 Unlike peripheral nociception, a number of neurochemical drivers are involved in the modulation of pain perception at the central level, resulting in a complex interplay of events that underlie the pathology of many chronic and neuropathic pain conditions ().Citation80,Citation83

Figure 1 Mechanism of peripheral versus central sensitization.

Abbreviations: AMPA, α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; ASIC, acid-sensing ion channels; BDNF, brain-derived neurotropic factor; 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine; IL, interleukin; NMDA, N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor; NGF, nerve growth factor; PG, prostaglandin; NK1, neurokinin-1; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TrkB, tyrosine receptor kinase B; TRPV, transient receptor potential vanilloid receptor.

Drugs that modulate the pathways leading to central sensitization act by increasing the level of biogenic amines and reducing the spontaneous ectopic discharges. These include serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs, such as duloxetine, paroxetine, venlafaxine), anticonvulsants (gabapentin and pregabalin) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs, such as amitriptyline, imipramine and desipramine).Citation84–Citation86

Wind-up phenomenon

Wind-up is the temporal summation of excitatory impulses following repeated firing of spinal dorsal neurons due to C-fiber discharges.Citation64 The process of wind-up begins with the release of excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate, which binds to the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (NMDA)/α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor.Citation87 Activation of these receptors, together with release of substance P from the C-fibers, initiates the depolarization of the cell membrane and triggers the intracellular release of Ca2+. Repetitive sensitization of NMDA receptors further contributes to hyperexcitability of the membrane, which aggravates the resulting response to pain, resembling an unending loop.Citation80,Citation88 Antagonism of NMDA receptor by drugs such as ketamine prevents the generation of excitatory response and provides therapeutic benefit in chronic neuropathic pain.Citation89

Neuroplasticity and pain

Apart from central sensitization, inflammation induces significant changes in the neuroplastic structure of the brain and spinal cord. Altered neuroplasticity is a characteristic feature of neuropathic pain and is often a consequence of tissue damage or injury.Citation90 The positive feedback-mediated structural repair following an injury or nerve damage may also contribute to selective degeneration and alteration of function, often progressing to the neuropathic state.Citation91 Modulation of peripheral nociceptor function may result in painful neuropathies, characterized by heightened sensitivity to noxious or normal stimuli and a pricking, tingling or burning pain. On the contrary, central nerve damage triggered by infection, metabolic disorders or mechanical insult may result in loss of pain sensation such as in diabetic neuropathy.Citation90

Modulation of nociceptive traffic

All events in the DH do not facilitate nociception. Spinal interneurons release amino acids (eg, γ-aminobutyric acid [GABA]) and neuropeptides (endogenous opioids) that bind to receptors on primary afferent and DH neurons and inhibit nociceptive transmission by presynaptic and postsynaptic mechanisms.

Descending transmission pathways are responsible for abolishing the ascending signals traveling up the central nervous system so that the pain perception is reduced,Citation64 via release of endorphins and monoamines.Citation92 Opioids like morphine act by modulation of both ascending and descending pain pathways ().Citation93

Progression from acute to chronic pain

Acute and chronic pain cannot be segregated into two distinct types; chronic pain is rather an extension of acute pain, resulting from poorly managed acute pain.Citation94 The metamorphosis of acute to chronic pain is believed to proceed through one of the following processes: central sensitization, modulation or modification of nociceptors, and altered neuroplasticity.Citation95,Citation96 Under normal circumstances, as a healing process begins, the noxious stimuli reduce and pain diminishes. However, in cases of persistent pain, peripheral and central sensitization most frequently transcends to hyperalgesia (increased response to less-painful stimuli) and allodynia (pain response to normally nonpainful stimuli). Altered spinal neuroplasticity as a result of glial cells modifying the neuronal cytoarchitecture is another important aspect of chronic pain and may be a consequence of repetitive nociceptive firing in the central neurons (reversible) or nerve damage due to neuropathy (irreversible).Citation97 Studies have reported substantial loss of gray matter in the brain and changes in the structure, sensitivity and activity of neurons as well as internal rewiring in certain chronic pain conditions.Citation91,Citation98,Citation99 These changes may be clinically manifested in the form of fibromyalgia or complex regional pain syndrome.Citation98 There is also a significant decline in neurotransmitter receptors and their function, which may explain the lack of efficacy with central opioid agonists in neuropathic pain.Citation91 While management of acute pain symptoms might seem to be the most rational approach from a clinician’s perspective, it is essential to evaluate the risk factors associated with pain chronification.Citation100 Increased pain intensity, loss of functionality and affected psychosocial ability are a few predictive factors for development of chronic pain.Citation101,Citation102 Studies have shown that assessment of functional and psychosocial outcomes is a highly favorable measure in predicting the risk of chronic pain.Citation103,Citation104

Undertreatment of pain

Pain is the most prevalent, yet frequently undertreated, medical condition globally.Citation105,Citation106 Untreated or inadequately treated pain is the major cause of depression and eventually leads to loss of productivity and functionality, as well as poor health-related QoL, of patients.Citation107,Citation108 There are several impediments that contribute to the undertreatment of pain in India, which include lack of awareness, regulatory restrictions on opioid use, physician attitudes, overuse of NSAIDs and insufficient resources for managing pain in primary care settings.Citation42,Citation109–Citation111 It is essential to minimize these barriers to ensure optimal treatment of pain.

Therapeutic management of pain

Evolution of analgesics

In the wake of increased understanding of the pathophysiology of pain, various receptors have been identified as potential targets for drug therapy over the years. In the early 1970s, Vane et alCitation112 proposed the involvement of prostaglandin inhibition as the mechanism of action of aspirin-like drugs. These findings paved the path for development of NSAIDs, targeting the COX-1 enzyme system involved in the synthesis of prostaglandins, thereby reducing both pain and associated inflammation. The earliest known marketed NSAIDs were ibuprofen and aspirin, which were followed up by similar compounds, with varying efficacies.Citation113 Acetaminophen, the safest analgesic till date was developed in 1946, after two synthetic antipyretics, acetanilide and phenacetin, were developed and had significant associated toxicities.Citation114 In the search for a more effective and safer analgesic, research was focused on the development of the selective COX-2 inhibitors celecoxib and rofecoxib.Citation115 However, there were severe concerns of cardiac toxicities observed with these agents, limiting their use.

Morphine and codeine were the earliest natural opioid analgesics to be developed and used in clinical practice. Further research led to the development of synthetic opioids such as fentanyl and pethidine, with increased efficacy and long-term activity. However, in the light of associated risk of overuse, addiction and misuse of these analgesics, it was recommended to follow a risk-management and monitoring program during opioid therapy. Tramadol, an opioid analgesic different from conventional opioids, was developed in 1977 and has since been routinely used in moderate-to-severe pain, owing to its high safety and efficacy.

Further scientific investigation into pain pathology has led to the development of anti-nerve growth factor (anti-NGF)- and anti-TRPV1-based therapies. However, these agents are still under clinical development, and there is a lack of conclusive evidence supporting their efficacy and safety in routine clinical practice.Citation116,Citation117 Deeper insights into the central pain pathways have uncovered some overlapping pathological factors implicated in pain, depression and other psychological disorders.Citation118 Antidepressant-induced increase in the neurotransmitters serotonin and norepinephrine has been thought to alleviate pain, the postulation being reinforced by the remarkable efficacy shown by antidepressants in chronic pain, particularly of neuropathic origin.Citation119 Similarly, the efficacy of the anticonvulsants pregabalin, gabapentin and carbamazepine was demonstrated in several clinical studies.Citation120 As a guidance to physicians treating chronic cancer pain, the WHO established an evidence-based three-step analgesic ladder that provides a stepwise approach for deciding treatment according to the intensity of pain.Citation121 This ladder has been widely adopted for use in noncancer pain settings.Citation122 However, the three-step ladder is not considered applicable anymore and has been modified to suit different clinical settings, due to the practical delays in administering pain relief for patients with severe pain and also due to concerns over the efficacy of low-dose opioids used in step two.

Evidence from several studies has highlighted the importance of nonpharmacological interventions for pain relief.Citation123 Exercises such as stretching and strengthening, relaxation, postural stabilization and yoga; therapeutic heat and cold packs; ergonomic adaptations; modification of daily activities; chiropractic treatment; massage or traction are some of the nonpharmacological approaches that are routinely used with pharmacological therapy.Citation124–Citation129

Therapeutic drug classes

A list of available therapies for pain management is represented in .

Table 2 Available therapies for treatment of pain

Need for individualized pain management

An individual’s perception of pain may be greatly influenced by the emotional and behavioral responses and is strongly correlated to his/her culture, personal history and genetic makeup.Citation130–Citation133 For instance, presence of different haplotypes of the catecholamine-O-methyltransferase gene has been linked to variability in pain perception in humans.Citation134 Thus, treatment for pain must be tailored for each individual and should focus on interruption of reinforcement of the pain behavior and modulation of the pain response. Important factors for consideration for treatment recommendation include individual’s response to prior appropriate treatment management, compliance and drug abuse/dependence behavior.Citation56 The biopsychosocial model of pain encompasses the biological, psychological and social aspects of pain and has been increasingly used in a variety of chronic pain settings.Citation135,Citation136 Since the experience of pain is heterogenic in nature; a “one size fits all” approach would not be the most ideal way to manage pain. In short, an individualized approach to treatment based on the genetic, cultural, social and behavioral aspects of the patient may help in the optimal management of pain across different clinical settings.Citation56,Citation137

Role of combination therapies

Combination therapies may consist of combination of two or more drugs administered separately or as fixed-dose combinations (FDCs) of two or more active ingredients in a single-dosage form.Citation138 Use of FDCs of analgesics represents a multimodal approach that is based on the integration of various mechanisms to result in pain relief.Citation139 FDCs have been hugely preferred to treat a variety of disorders owing to their safety and efficacy. Additionally, use of FDCs may improve patient adherence to therapy and reduce the cost associated with multiple medications.Citation140 However, not all FDCs are rational, and the majority of them may present no evidence of improved efficacy or tolerability.Citation141,Citation142 In India, FDCs have been used generously, notwithstanding the complete lack of efficacy with some combinations.Citation143 The Central Drugs Standard Control Organization (CDSCO) has taken cognizance of the increased use of irrational drug combinations by physicians in India and has recently banned more than 300 FDCs from the market.Citation144 From a physician’s perspective, the rationale for use of FDCs must identify clear association between FDC use and increased efficacy or reduced adverse events. Furthermore, from a regulatory perspective, the components of an FDC must possess complementary pharmacokinetic profiles and should not have supra-additive toxicity.

The US Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) draft guidance for industry mandates the fulfillment of some necessary conditions prior to the approval of analgesic FDCs. Thus, an FDC awaiting FDA approval must demonstrate strong evidence of efficacy over the available single-agent therapy in well-controlled single- or multiple-dose clinical studies. Moreover, each component of the FDC must contribute to the overall efficacy and safety of the product, in order to justify its use over single-agent therapies.Citation145 A similar guidance document has been developed by the CDSCO to guide the development of FDCs in India.Citation146 A list of approved analgesic FDCs in India is provided by the CDSCO.Citation147

Reasons for mismanagement of pain

Adequate treatment according to national and international treatment guidelines can result in sufficient pain relief in majority of the patients. However, barriers to the use of analgesics can result in undertreatment of pain. Other than institutional barriers such as government regulations regarding opioid prescription and irregularities in the treatment of patients with pain, physician and patient barriers hinder effective management of pain.

Physician barriers

Physician’s knowledge and understanding regarding patients’ pain, principles of treating pain, analgesics ladder and knowledge about the efficacy of different routes of opioid administration are very important for pain management.Citation148–Citation152 Another factor affecting inadequate assessment of pain by physicians included concerns regarding side effects or tolerance to opioids.Citation43,Citation153–Citation155 In cancer patients, inadequate pain assessment was considered a major barrier (20%–80%) in pain assessment.Citation42,Citation148,Citation149 The physicians either do not use an appropriate method to measure the pain intensity or fail to appropriately classify the pain. Misconceptions regarding the regulations governing opioid use also exist.Citation156

Concerns regarding addiction to or physical dependence on, as well as side effects of opioids prevent physicians from prescribing opioids according to standardized guidelines.Citation68,Citation127,Citation157–Citation159 According to the guidelines by the WHO, strong opioids should be the first choice of treatment for moderate-to-severe pain and the use of these opioids must be continuously personalized based on patients’ response in terms of pain relief. In a study by Tournebize et al,Citation160 more than 50% of surveyed physicians reported insufficient adherence to treatment guidelines for chronic pain. Studies have also shown that physicians hesitate to administer adequate doses of opioids because of the fear of the potential development of tolerance by the patient.Citation42,Citation161,Citation162 Most often, physicians do not consider assessment of pain as a priority and, as a result, do not give pain relief its due importance. Furthermore, a patient’s self-report of pain, considered the best indication of pain, is viewed with skepticism.

Patient barriers

Cognitive barrier results from patients’ lack of understanding about the different options of pain management, along with attitudes and beliefs that not only affect patients’ pain communication and adherence to analgesic regimen but also have a negative impact on the outcomes of pain management.Citation163

Many patients lack the knowledge of the principles involved in effective pain management and have concerns about taking pain medication (mostly concerns about addiction and side effects of pain medication). A few researchers believe that there is a relationship between better knowledge and less pain intensity or between more negative beliefs and more intensive pain.Citation164–Citation169 However, this association was either partially confirmed or not confirmed by other researchers.Citation170,Citation171

Patients beliefs and attitudes that hinder pain management include the following: fear of addiction, that originates from a misunderstanding of the relationship between psychological addiction, physical dependence and tolerance; concerns about analgesic use (side effects); concerns about pain communication due to age, language, cultural traditions or other illness (communication issues between patients, nurses and doctors [sensory barrier]; willingness to tolerate pain to be a good patient and to not trouble the family); not adapting adequately to the possibility of controlling pain in general (stigma of using pain medication, stoicism about dealing with pain, assuming that pain is a part of the disease and suffering, concerns regarding the capability of the caregiver to understand their needs, hesitation to question authority); and inadequate adherence to pain medication (sensory barrier).Citation42,Citation155,Citation166,Citation169,Citation172–Citation175 Financial barriers could also result in reduced adherence to treatment.

Management myths

Several myths about pain and its treatment exist in our society, which ultimately prevent the patient from receiving adequate care. According to the American Chronic Pain Association, some of the commonly accepted beliefs revolve around the perception (pain is an emotional and not a physical disorder) and treatment of pain (analgesic therapies may not be effective or may lead to addiction).Citation176 In addition, undertreatment of pain in the elderly and children may be primarily due to the assumption that pain cannot be felt by newborns and babies but is an acceptable and natural part of the aging process and therefore may not warrant medical attention.Citation177 It is essential to disprove these myths by promoting awareness among patients, physicians and the society in general.

Comorbidities

Presence of comorbid medical conditions may not only influence the response to analgesics but may present difficulties in diagnosis as well. The most commonly associated psychological comorbidities in pain are depression and anxiety.Citation178–Citation180 These may be preexisting or may result from the pain itself, often aggravated in untreated or undertreated chronic pain.Citation181 Presence of depression is known to have considerable impact on outcomes of pain treatment, signifying the two-way relationship between pain and depression. A systematic review of studies correlating the effect of depression on pain showed increased severity, intensity and duration of pain in depressed patients.Citation124 Functional assessment using valid tools may indicate the presence of underlying symptoms, necessitating the use of antidepressant therapy, which can in turn effectively help control pain.Citation126,Citation182 Until recently, the outcome of pain therapies was evaluated on the basis of reduction in pain intensity and improvement in sensory/motor ability, seldom delving into the psychological or cognitive aspects that frequently led to mismanaged pain. Clinical investigations over the years have resulted in the use of cognitive behavioral therapy in pain treatment programs, with remarkable efficacy in the acute and chronic pain settings.Citation183,Citation184

Management recommendations

General considerations (evaluating a patient with pain)

The recommendations are based on graded evidence as explained previously. The grades are mentioned in parenthesis next to each recommendation.

History

A thorough evaluation of the patient profile, patient history and presence of comorbid conditions is necessary as a first step toward pain diagnosis (C).

Diagnosis should involve measurement of pain intensity, physical examination, sensory examination, motor examination and evaluation of cognitive and functional well-being (B).

Assessment and monitoring

Identify and use appropriate pain assessment tools (A) For the purpose of designing treatment strategies for managing pain, it is essential to assess the severity of the pain. Use of pain assessment scales may help in the diagnosis of the disease, design of treatment strategies, monitoring and evaluation of outcome of therapy or for predicting the impact of pain on functional outcomes of a patient ().Citation185 Factors that should be taken into consideration while selecting the appropriate pain assessment method include sensitivity and specificity, usefulness or value of the assessment tool, objective of the assessment, age of the patient and extent of symptoms presented by the patient.Citation186

Table 3 Different pain assessment scales for measuring the intensity of pain

Sensory examination

Components of a sensory examination include light touch, pinprick, temperature (hot or cold) and vibration.Citation187 Quantitative sensory testing (QST) might help distinguish between various types of neuropathic pain.Citation188,Citation189 In patients with neuropathy, the threshold for pinprick and thermal sensations are increased, while increased sensitivity to light touch may indicate presence of allodynia or hyperalgesia, which may point toward painful inflammation or fibromyalgia with a central neuropathic origin.Citation190–Citation192 The QST has also been used in the diagnosis of osteoarthritis and other musculoskeletal conditions, although not as a sole measure.Citation193

Motor examination

Evaluation of motor function is an important method of diagnosing musculoskeletal pain, especially back pain and neck pain. Exercises such as neck rotation and neck flexion or extension tests may help determine the localization and intensity of pain (D).Citation194

Diagnostic tests

Examination by X-rays is the most common method used to confirm the localization of pain, particularly in LBP, neck pain, joint pain or pain associated with internal organs.Citation147 Use of computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) might be useful in cases in which diagnosis by physical examination or X-ray may be insufficient or if any underlying damage to the CNS is suspected to be involved.Citation195 Further details are presented in the Supplementary material section.

Comorbidities

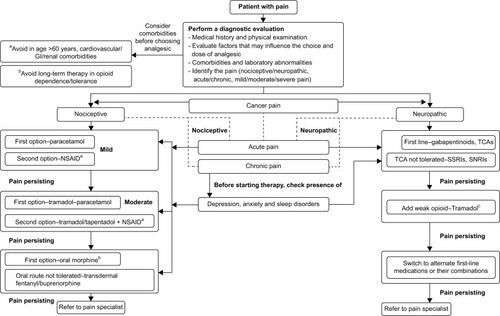

Since comorbidities may influence pain perception and affect the treatment outcomes, it is necessary to carry out screening of the patient for possible physical illnesses (liver impairments, gastrointestinal diseases, renal impairments, physical dependence to opioids and so on) and psychiatric comorbidities (depression, anxiety, psychological disorders) prior to initiating treatment ().

Figure 3 Pain algorithm.

Abbreviations: GI, gastrointestinal; NP, neuropathic pain; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; SNRI, serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant.

Decide treatment goals

Prior to starting treatment, it is essential to decide the treatment goals so as to prevent undertreatment. It is important to consider the ethical implications of the associated treatment. The following questions may help: how severe is the pain? Is the pain associated with disability or loss of function? What are the existing comorbidities? Is psychosocial function impaired? Is opioid therapy required?

According to Cohen and Jangro,Citation196 treatment goals need to be broader, achieving a little more than pain reduction (must include QoL and the functional impact of pain treatment), and must be realistic, in order to ensure optimal therapy with minimal side effects.

Investigations for neuropathic pain

A detailed diagnosis of neuropathic pain involves, in addition to pain assessment tools (using neuropathic pain scales) and QST, evaluation of neurological function using functional neuroimaging, neurophysiology studies, skin biopsy techniques and other laboratory testing methods.Citation197 Additional laboratory investigations include microneurography studies, laser-evoked potentials, electrophysiology studies and nociceptive reflexes.Citation189

Pharmacological management

In order to understand the nature of pain and to determine the treatment course, it is essential to distinguish the physical causes of pain in addition to assessing the mental and environmental factors.

The choice of analgesic prescribed is based on the type of pain, duration of pain and comorbidities. A few years ago, NSAIDs, acetaminophen and opioids were prescribed in the treatment of all types of pain. This methodology is now considered ineffective, and with an increase in the awareness regarding different classifications of pain, mechanism-specific treatment is recommended.

Comorbidities influencing analgesic use

Studies have shown that a number of comorbidities influence the treatment outcomes of analgesic therapy. It is widely known that several chronic pain conditions are accompanied by psychosocial comorbidities such as anxiety and depression, which may amplify the pain perception, physical function, adaptation and treatment response.Citation198,Citation199 Systematic screening of patients for any associated psychiatric comorbidity may support the physician in deciding the treatment plan. In the case of suspected depression, antidepressants may be added to the therapeutic regimen to control the clinical symptoms.Citation200 While psychiatric comorbidities significantly affect the emotional response to pain, any coexisting physical comorbidities may affect the efficacy and tolerability of the analgesic. For example, decreased liver function may significantly affect the metabolism of NSAIDs and opioids, leading to increased levels in blood and associated toxicity. Preliminary screening by performing liver function tests and assessment of the Child–Pugh score may be important in determining liver failure.Citation201 Similar considerations are necessitated in suspected gastrointestinal or renal comorbidities.Citation202,Citation203

Duration of pain

Duration of pain is a decisive factor guiding the choice of an appropriate analgesic regimen.Citation204 However, duration of pain should always be correlated with the pain intensity.Citation158,Citation199

Acute pain

The primary pain management goal here is early intervention to reduce the pain to acceptable levels. Most of the acute pain is nociceptive and treatment for acute pain involves a combination of paracetamol, opioids and some topical agents. Mild somatic acute pain could be treated with paracetamol, NSAIDs, topical anesthetics and physical treatments such as ice, compression and so on. For acute visceral pain, NSAIDs, opioids, corticosteroids and agents modulating the central neuronal activity (TRPV1 antagonists) may be used, depending on the underlying comorbidity. For moderate-to-severe pain, a combination of opioids and nonopioids could offer optimal pain relief. In cases of pain from trauma or surgical procedures, systemic medication would have to be administered.

Chronic pain

Management goals for chronic pain include reducing the suffering due to pain and the associated emotional distress, in addition to increasing the coping ability and psychosocial well-being of the patient, by targeting the hypersensitive nervous system.Citation205 Multimodal therapy involving a combination of treatments is recommended for treatment of chronic cancer or noncancer pain. The treatment for CNCP could include nonopioids (paracetamol, NSAIDs and selective COX-2 inhibitors), opioids, analgesics, TCAs, corticosteroids, muscle relaxants, sedatives and anxiolytics.

Nociceptive pain

Nociceptive pain is generally time limited as the pain resolves when the tissue damage heals, but it may also be persistent when associated with inflammatory disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis. Treatment for localized pain should be started with the use of topical or oral NSAIDs.Citation56 Moderate-to-severe pain unresponsive to NSAIDs may be treated with opioids to manage symptoms and control inflammation.Citation206 Additionally, corticosteroids and immune-modulating agents (biologics) can also be used to manage inflammation in arthritic pain.Citation207

Neuropathic pain

Peripheral neuropathic pain manifests as stimulus-independent pain or stimulus-evoked pain (pain hypersensitivity triggered by a stimulus following damage to sensory neurons). Neuropathic pain may persist for months or years beyond the normal healing time of any damaged tissues. Evidence from randomized controlled studies (RCTs) and systematic reviews have confirmed the efficacy of TCAs (amitriptyline and nortriptyline), antiseizure medications (pregabalin, gabapentin and carbamazepine) and opioids in the treatment of various neuropathic conditions.Citation85,Citation86,Citation208–Citation212 Evidence supports the use of opioids as second- or third-line therapies for neuropathic pain, particularly of peripheral origin () (A).Citation208,Citation209 However, further confirmation from well-controlled studies is warranted to establish the efficacy of these agents in complex neuropathies.Citation189,Citation213

Mild, moderate and severe pain

Treatment recommendations are also dependent on the severity of pain. Acetaminophen and other mild NSAIDs such as aspirin are the preferred treatment for mild chronic pain and may be used to supplement other agents in treating mild-to-moderate pain.Citation56 However, acetaminophen lacks anti-inflammatory effects, limiting its use in pain associated with inflammatory diseases such as arthritis. NSAIDs are recommended for periodic flare-ups of mild-to-moderate inflammatory or nonneuropathic pain. For management of persistent moderate-to-severe pain, opioid therapy is the most sought-after treatment. Opioids are considered effective in the treatment of neuropathic pain that is not responsive to initial therapies, but not in the treatment of inflammatory, mechanical or compressive pain. Certain strong opioids, however, do not necessarily improve functional or psychological status and should be administered under adequate supervision.Citation214–Citation216

A person’s experience of pain generally manifests itself in emotional and behavioral responses and is strongly correlated to the culture, personal history and perceptions of the individual.Citation130 Thus, treatment for pain must be tailored for each individual patient and should focus on interruption of reinforcement of the pain behavior and modulation of the pain response. Important factors to be considered for treatment recommendation include individual’s response to prior appropriate treatment management, compliance and drug abuse/dependence behavior.Citation56 An understanding of cultural-based attitudes about pain is critical in the management of pain.

Treatment in special populations

Undertreatment of pain in special populations, such as the elderly, children or patients with renal/hepatic impairment, results from inadequate pain assessment and efficacy issues. Pain treatment in these populations must be performed following careful consideration of adverse events and the pharmacokinetic profile of the analgesic.

Elderly

Studies report that the prevalence of pain is higher in the elderly population, with high proportion of patients with disability and poor QoL.Citation62,Citation217 The most commonly occurring pain conditions in the elderly are rheumatoid or osteoarthritis, cancer and diabetic neuropathy.Citation218 In addition, elderly patients with chronic pain present several clinical comorbidities, which may influence the outcome of pain therapy. These may include gastrointestinal/renal/hepatic dysfunction, depression, anxiety and cognitive impairment, among others.Citation219,Citation220 Due to the limited evidence from clinical studies on the geriatric population with pain,Citation221 the health care practitioner needs to evaluate the possible risk factors that may impede effective analgesia. NSAIDs should be avoided in such patients due to the potential for gastrointestinal bleeding and renal toxicity. Opioids such as morphine, codeine, fentanyl or oxycodone may cause constipation or respiratory depression and should be used with caution, preferably in low doses and along with laxatives.Citation222 Paracetamol is the analgesic of choice for the geriatric population with pain.

Children

Pain in children may be mostly due to injuries, burns, inflammation and chronic illnesses such as cancer, HIV/AIDS or postoperative status. The WHO guidelines on management of chronic pain in children emphasize the importance of pain assessment in children.Citation223 Since self-reports of pain severity cannot be obtained in infants or small children, pain assessment entirely depends upon the clinician’s reports. Symptoms of crying, agitation, irritation or facial expression may be indicative of pain in infants. For children >4 years of age, Faces Pain Scale may be used for pain assessment.Citation224,Citation225 Pharmacological therapy of pain in children should take into account the age, pain intensity, underlying disease or comorbidities as well as the functional ability. The first-line therapy generally includes safer analgesics such as paracetamol, followed by ibuprofen.Citation223 The second-line therapy may include other NSAIDs. Strong opioids should only be used in moderate-to-severe pain.Citation226 The most preferred route of medication administration should be oral, either as tablets or as syrups.Citation134

Pregnant and lactating women

During pregnancy, women may experience LBP, joint pain, as well as abdominal and pelvic pain, among other conditions. Analgesic treatment during pregnancy and lactation may be difficult considering certain medications can potentially harm the fetus or may pass through breast milk and affect a nursing infant. Administration of NSAIDs in the first trimester has been linked to premature ductal closure and should be avoided.Citation227 Aspirin may be used in the first trimester but should be avoided near term, as it may delay labor and cause hemostatic abnormalities.Citation228 Paracetamol and opioids are relatively safer analgesics to use in pregnant women. In the case of lactating women, paracetamol and NSAIDs may be safe to use, while opioids should be avoided due to the risk of toxicity and dependence.Citation229

Renal impairment

A majority of analgesics are excreted by the renal route, and it is important to assess kidney function prior to administering analgesics for chronic pain. Since impaired renal function may lead to accumulation of drugs, there are chances of toxicity in such patients. Clinicians should conduct adequate assessment of kidney function by estimating serum creatinine values and the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR).Citation203 An eGFR of <60 mL/min/1.73m2 may warrant dose adjustment.Citation230 NSAIDs, such as indomethacin, naproxen, diclofenac and ibuprofen, have been shown to decrease the GFR and increase the possibility of edema due to prostaglandin-mediated inhibition of renin.Citation231 Therefore, NSAIDs are best avoided in patients with renal impairment. Alternatives to NSAIDs are paracetamol and opioids such as codeine, tramadol or buprenorphine;Citation232 morphine and codeine are undialyzable and should be avoided in patients who are undergoing hemodialysis.Citation231 For moderate-to-severe pain, fentanyl can be safely administered to patients with renal dysfunction or those who require dialysis (although caution needs to be exercised in such patients as fentanyl is poorly dialyzable).Citation232,Citation233

Liver failure

Deciding analgesic therapy for patients with hepatic impairment can be a challenge, since most analgesics undergo hepatic metabolism. Cirrhosis is the most prevalent manifestation of liver disease, and it may be caused due to excessive alcohol intake, hepatitis infection or drug-induced toxicity. Since liver is the main site of metabolism for paracetamol, NSAIDs and opioids such as morphine, its dysfunction may lead to increased blood levels of these drugs, particularly those that are primarily metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes.Citation234 On the contrary, changes in CYP enzymes may result in decreased efficacy of codeine and tramadol, which undergo biotransformation to active metabolites.Citation235 Thus, a thorough understanding of the pharmacokinetic profile of analgesics may help in deciding the appropriate pharmacotherapy for patients with liver dysfunction.Citation236 For instance, although paracetamol undergoes metabolic conversion to a hepatotoxic metabolite N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine,Citation237 clinically significant toxicity is observed only at large doses, and small doses of this drug may appear to be safe in such patients.Citation238 Dose adjustment should be considered while administering NSAIDs and opioids to patients with hepatic impairment.

Disease-specific treatment recommendations are presented in the Supplementary materials section.

Author contributions

All authors contributed towards drafting and critically revising the review and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors met International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria and all those who fulfilled those criteria are listed as authors. All authors provided direction and comments on the manuscript, made the final decision about where to publish as well as approved the submission of the manuscript to the journal.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the efforts of other members of the Pain Working Group who contributed significantly to the development of this manuscript, namely, SS Sukumar, Hammad Usmani, Rajeev Rao, Ananth Hazare, PR Krishnan, Poorna Chandra and Umesh Gupta. Padmini Deshpande (Siro Clinpharm Pvt Ltd) provided writing assistance, and Dr Sangita Patil (SIRO Clinpharm Pvt Ltd) provided additional editorial support for the development of this manuscript. This study was funded by Johnson & Johnson Pvt Ltd, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India.

Supplementary materials

Pain Assessment Scales

Brief Pain Inventory (BPI)

Originally developed for assessment of pain in cancer patients, the BPI has been successfully used in a variety of clinical settings.Citation1 In the BPI, severity of pain is measured across four grades, and the degree of interference of pain is evaluated across seven parameters: general activity, walking, work, mood, enjoyment of life, relationship with others and sleep.Citation2 Several modified versions of the BPI have been developed to adapt to the requirements of the target population across different geographical settings. The reliability of the Hindi version of the BPI was demonstrated in a clinical trial in North India by Saxena et al.Citation3

McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ)

Developed by Melzack and Torgerson in 1971,Citation4 the MPQ is a multidimensional pain assessment tool consisting of three major classes of word descriptors (total of 78 words) reflecting sensory, affective and evaluative components. It also contains a pain intensity scale ranging from one to five to rate the severity of the pain.Citation5 MPQ and the short-form MPQ (SF-MPQ) are valid and reliable tools to assess chronic pain, particularly cancer pain, in adults.Citation6–Citation9 The MPQ can also be used in the assessment of neuropathic and arthritic pain.Citation10–Citation12

Visual Analog Scale (VAS)

The VAS is a simple, easily administered, single-item tool to assess pain severity, especially in acute pain.Citation13 VAS consists of a horizontal or vertical rating scale (1–10 cm) with verbal descriptors of “no pain” and “pain as bad as it could be.” The patient is asked to mark the level of pain on the numerical scale of 1–10 cm (or 1–100 mm). Several studies have validated the use of VAS in acute and chronic pain.Citation13–Citation15

Numerical Rating Scale (NRS)

The NRS consists of a numerical scale similar to the VAS, however, with numbers marked from one to ten, ranging from “no pain” to “worst pain imaginable”. The NRS is easy to administer via paper-and-pencil, telephone, fax or any computerized system and has demonstrated superiority over the VAS across different studies,Citation16,Citation17 especially in illiterate or elderly populations.Citation18–Citation20

Verbal Rating Scale (VRS)

The VRS scale is composed of a series of adjectives along with numbers to best describe the intensity of the pain. VRS has been reported to be well correlated with the VAS, in terms of simplicity and reliability.Citation21,Citation22 However, the VRS scale has been found to be less sensitive to changes in pain intensity and is considered highly subjective.Citation22–Citation24

Faces Pain Scale (FPS)

For the self-reporting of pain severity in children, elderly and other special populations, FPS may be used. In this scale, pain is graded by means of facial expressions. FPS and the revised FPS have demonstrated reliability in predicting the severity of pain in children aged 4–8 years and in patients with cognitive impairment.Citation25–Citation28

Disease-specific assessment scales

Due to the methodological problems faced during the assessment of pain using standard tools,Citation29 disease-specific pain measurement questionnaires have been developed with an aim to correctly capture the nature and severity of pain in different pathophysiological conditions.Citation30 Use of Neuropathic Pain Scale (NPS), Neuropathic Pain Questionnaire (NPQ) and Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs (LANSS) Pain Scale is recommended to differentiate between nociceptive and neuropathic pain (A).

Cognitive and behavioral assessment scales

Pain perception is greatly influenced by the psychological and emotional status of the patient. Chronic pain may induce notable changes in the behavior, cognition and social abilities of a person. Pain is also accompanied by a state of fear, anxiety, depression and negative beliefs. These psychological traits may serve as important predictors of chronic pain and disability and may determine treatment outcomes. Therefore, a comprehensive pain management program should also involve psychological, cognitive and behavioral assessment of the patient. For this purpose, tools such as Pain Beliefs and Perceptions Inventory (PBPI), Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale (PASS), Cognitive Evaluation Questionnaire and the Patient Attitude Questionnaire (PAQ) may be used.

Assessment in elderly or cognitively impaired patients

Patients’ self-reports of pain have been proven to be more reliable tools for accurate diagnosis of pain and treatment of pain. However, obtaining detailed self-reports in both patients with cognitive impairment and the elderly can prove to be a major challenge and, therefore, requires the use of pain assessment tools that are relatively easy and adequately describe the pain experience.Citation31 For cognitively sound older adults, the VRS, NRS or FPS may be easy and reliable to use (A), whereas in elderly with symptoms of dementia or cognitive impairment,Citation32 the Abbey’s Pain Scale, Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia Scale (PAINAD) and Pain Assessment for the Dementing Elderly (PADE) have demonstrated reliability (A).Citation33–Citation35

Disease-specific treatment recommendations

Low-back pain (LBP)

Classification

LBP is localized to the lumbar vertebrae (L1–l5) just above the gluteus muscle.

LBP can be classified by duration as acute (<6 weeks), subacute (6–12 weeks) and chronic (>12 weeks).

LBP may be classified by cause as mechanical (strains/sprains or fractures), nonmechanical (tumors) and referred pain (kidney or gall stones or pain in nearby tissue).Citation36

LBP is classified by mechanism or “diagnostic triage” into serious spinal pathology (accompanied by “red flags”), nerve root pain/radicular pain and nonspecific LBP.

Diagnosis

Use diagnostic methods such as physical examination, X-rays, ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT) scans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), diskography, bone scans and blood tests (B).Citation37–Citation39

Identify “red flags”, which are signs/symptoms that are unlikely to be observed in normal LBP and generally indicate involvement of serious pathology. Identifying the red flags may help diagnose underlying chronic conditions, such as cancer (C).

Identify “yellow flags’, which represent the psychosocial barriers that may influence the subjective response to pain and which may delay recovery or indicate the risk of chronification or disability (C).

Treatment

Initiate treatment with acetaminophen and mild NSAIDs (ibuprofen, diclofenac) as first-line therapy (A).Citation40,Citation41

Second-line therapy should typically involve a combination of NSAIDs and mild opioids (codeine, tramadol) (A),Citation41,Citation42 followed by moderate-to-strong opioids (morphine, fentanyl) in severe pain.Citation42,Citation43

Third-line therapy should be initiated in case a central origin is suspected or if pain significantly affects the physical, mental and social behavior of patients; it may include anticonvulsants (gabapentin, pregabalin),Citation44 sedatives (benzodiazepines) and antidepressants (amitriptyline, nortriptyline) (A).Citation45–Citation47

Neck pain

Classification

Neck pain can be classified into four classes according to the impact of pain on body function and movement, as follows:

Pain with mobility deficits

Pain with headache

Pain with radiating pain

Pain with impaired movement.

Based on the causative mechanism, neck pain may be classified as follows:

Axial neck pain caused due to incorrect posture, physical stress or fatigue

Whiplash-associated disorder (WAD) due to pain in the muscles, joints, tendons and ligaments due to injuries or impact

Cervical radiculopathy and myelopathy due to changes to the sensory/motor function of cervical nerves or compression of spinal cord.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis should be preceded by careful evaluation of patient, the nature and extent of pain and any additional symptoms such as headaches, nausea, vomiting, vertigo or other distress (C).Citation48

Symptom assessment may help in differentiating different types of neck pains. Sharp, shooting or tingling pain may indicate a radicular origin, whereas dull, aching pain accompanied with soreness or tenderness may point toward axial pain (C).

Physical examination and self-report questionnaires are more valid assessment tools and should be preferred over diagnostic tests such as imaging, electrophysiology or blood tests, which have failed to demonstrate reliability (C).

Identify the “red flags”, which may include trauma, infections, history of pain, malignancy or major trauma, in addition to weight loss, chest pain, nausea, vomiting or fever (C).Citation49

Treatment

Exercise and physiotherapy are the most effective interventional methods with proven efficacy in neck pain (A).Citation50–Citation53

Analgesics such as acetaminophen and NSAIDs may be used for acute pain, and weak opioids may be used for chronic episodes, as first-line therapies (A).Citation49

Antidepressants, muscle relaxants and strong opioids may be reserved for refractory cases or after failure of other interventional methods (C).Citation48

Headache

Classification

According to the International Headache Society, primary headaches can be classified into migraine headaches, cluster headaches and tension-type headaches. Migraine headaches result from migraine disorders, which are further categorized as migraine with aura, migraine without aura, childhood migraine or retinal migraine depending upon the presentation.Citation54–Citation56

Secondary headaches may be caused due to an underlying disorder such as tumors.

Diagnosis

Preliminary diagnosis can be performed through symptom assessment and detailed evaluation of patient profile and history or presence of underlying disorders.

A typical migraine attack is triggered by physical activity and may be suspected if symptoms involve severe pulsating or throbbing headache on one or both sides of the head, sometimes accompanied by visual aura, sensitivity to light, nausea or vomiting. Frequently occurring migraine attacks (≥15 days per month for >3 months) despite continuing medication may be regarded as chronic migraine; the duration of headache may be 4–72 hours.

Tension-type headaches, also known as ordinary headaches, may be triggered by stress. The pain is usually bilateral, with pressing/tightening quality and is not usually accompanied by nausea, vomiting or light sensitivity. Persistent tension-type headache may indicate the presence of serious underlying disorders. These headaches may last from a few minutes to days (up to 7 days).

Cluster headaches usually involve severe unilateral pain around the eyes (orbital pain), forehead or sides of the head (temporal pain). These headaches may last for 10 minutes to 4 hours.

Diagnosis by neuroimaging techniques should be reserved for patients who have persistent pain lasting 6-month duration, often in the absence of migraine and accompanied by neurologic symptoms such as confusion, visual problems and hallucinations; also to be used in the case of patients with history of such disorders in the past (B).Citation57

Treatment

Migraine headache: begin initial treatment with oral triptans (sumatriptan or zolmitriptan), followed by the antiemetics prochlorperazine or chlorpromazine in case of nausea and vomiting (A); opioids and antidepressants may be considered as second-line therapy. In children, initial treatment may be initiated with acetaminophen and ibuprofen, followed by sumatriptan nasal spray or oral triptans (A).Citation58–Citation68

Cluster and tension-type headaches: treatment for cluster and tension-type headaches should consist of acetaminophen, low-dose NSAIDs (ibuprofen, naproxen and diclofenac), followed by an NSAID–caffeine or acetaminophen–caffeine combination as second-line therapy (A).Citation69–Citation72

Arthritic pain

Classification

Although arthritic pain involves both rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis, primarily it can be classified as inflammatory arthritis, noninflammatory arthritis or arthralgia. Inflammatory pain involves the inflammation of the joints, synovial cavity or synovium. Noninflammatory arthritic pain may result from altered joint mechanics, while arthralgia represents joint tenderness in absence of inflammation, usually resulting from an underlying condition such as fibromyalgia.Citation73

Diagnosis

Carefully observe symptoms of swelling, tenderness, redness and stiffness, as well as checking joint movement, wrist movement, rotation, movement or function (B).Citation73

The diagnosis may be confirmed using bone aspiration tests and imaging tests (B).

Treatment

First-line therapy should consist of acetaminophen and oral or topical NSAIDs (ibuprofen, diclofenac or naproxen) (A).Citation73–Citation75

Second-line therapy with opioids (tramadol, morphine and oxycodone) should be considered only if the patient is unable to tolerate NSAIDs or if pain persists despite NSAID medication (A).

Table S1 Treatment recommendations

References

- CleelandCRyanKPain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain InventoryAnn Acad Med Singapore19942321291388080219

- CleelandCSRyanKThe Brief Pain InventoryPain Research Group1991 Available from: http://sosmanuals.com/manuals/cae48184b-7bae3b1d85105ea85375b60.pdfAccessed June 2016

- SaxenaAMendozaTCleelandCSThe assessment of cancer pain in north India: the validation of the Hindi Brief Pain Inventory – BPI-HJ Pain Symptom Manag19991712741

- MelzackRTogersonWSOn the language of painAnesthesiology197134150594924784

- MelzackRThe McGill Pain Questionnaire: major properties and scoring methodsPain1975132772991235985

- NgamkhamSVincentCFinneganLHoldenJEWangZJWilkieDJThe McGill pain questionnaire as a multidimensional measure in people with cancer: an integrative reviewPain Manag Nurs2012131275122341138

- DudgeonDRaubertasRFRosenthalSNThe short-form McGill pain questionnaire in chronic cancer painJ Pain Symptom Manag199384191195

- GrahamCBondSSGerkovichMMCookMRUse of the McGill pain questionnaire in the assessment of cancer pain: replicability and consistencyPain1980833773877402695

- KremerEFAtkinsonJHIgnelziRJPain measurement: the affective dimensional measure of the McGill Pain questionnaire with a cancer pain populationPain19821221531637070825

- LovejoyTITurkDCMorascoBJEvaluation of the psychometric properties of the revised Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ-2)J Pain201213121250125723182230

- BurckhardtCSJonesKDAdult measures of pain: The McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), Rheumatoid Arthritis Pain Scale (RAPS), Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), Verbal Descriptive Scale (VDS), Visual Analog Scale (VAS), and West Haven-Yale Multidisciplinary Pain Inventory (WHYMPI)Arthritis Care Res200349S5S96S104

- KachooeiAREbrahimzadehMHErfani-SayyarRSalehiMSalimiERaziSShort Form-McGill Pain Questionnaire-2 (SF-MPQ-2): a cross-cultural adaptation and validation study of the Persian version in patients with knee osteoarthritisArch Bone Jt Surg201531455025692169

- BijurPESilverWGallagherEJReliability of the visual analog scale for measurement of acute painAcad Emerg Med20018121153115711733293

- SeymourRThe use of pain scales in assessing the efficacy of analgesics in post-operative dental painEur J Clin Pharmacol19822354414447151849

- PriceDDMcGrathPARafiiABuckinghamBThe validation of visual analogue scales as ratio scale measures for chronic and experimental painPain198317145566226917

- PaiceJACohenFLValidity of a verbally administered numeric rating scale to measure cancer pain intensityCancer Nurs199720288939145556

- JensenMPKarolyPBraverSThe measurement of clinical pain intensity: a comparison of six methodsPain19862711171263785962

- FerrazMBQuaresmaMAquinoLAtraETugwellPGoldsmithCReliability of pain scales in the assessment of literate and illiterate patients with rheumatoid arthritisJ Rheumatol1990178102210242213777

- HjermstadMJFayersPMHaugenDFStudies comparing Numerical Rating Scales, Verbal Rating Scales, and Visual Analogue Scales for assessment of pain intensity in adults: a systematic literature reviewJ Pain Symptom Manag201141610731093

- BriggsMClossJSA descriptive study of the use of visual analogue scales and verbal rating scales for the assessment of postoperative pain in orthopedic patientsJ Pain Symptom Manag1999186438446

- LittmanGSWalkerBRSchneiderBEReassessment of verbal and visual analog ratings in analgesic studiesClin Pharmacol Ther198538116233891192

- HoldgateAAshaSCraigJThompsonJComparison of a verbal numeric rating scale with the visual analogue scale for the measurement of acute painEmerg Med (Fremantle)2003155–644144614992058

- AicherBPeilHPeilBDienerHPain measurement: Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and Verbal Rating Scale (VRS) in clinical trials with OTC analgesics in headacheCephalalgia201232318519722332207

- LangleyGSheppeardHProblems associated with pain measurement in arthritis: comparison of the visual analogue and verbal rating scalesClin Exp Rheumatol198323231234

- BieriDReeveRAChampionGDAddicoatLZieglerJBThe Faces Pain Scale for the self-assessment of the severity of pain experienced by children: development, initial validation, and preliminary investigation for ratio scale propertiesPain19904121391502367140

- GoodenoughBAddicoatLChampionGDPain in 4-to 6-year-old children receiving intramuscular injections: a comparison of the Faces Pain Scale with other self-report and behavioral measuresClin J Pain199713160739084953

- WareLJEppsCDHerrKPackardAEvaluation of the revised faces pain scale, verbal descriptor scale, numeric rating scale, and Iowa pain thermometer in older minority adultsPain Manag Nurs20067311712516931417

- HicksCLvon BaeyerCLSpaffordPAvan KorlaarIGoodenoughBThe Faces Pain Scale–Revised: toward a common metric in pediatric pain measurementPain200193217318311427329

- OhnhausEEAdlerRMethodological problems in the measurement of pain: a comparison between the verbal rating scale and the visual analogue scalePain197514379384800639

- SalaffiFCiapettiACarottiMPain assessment strategies in patients with musculoskeletal conditionsReumatismo201264421622923024966

- HerrKCoynePJMcCafferyMManworrenRMerkelSPain assessment in the patient unable to self-report: position statement with clinical practice recommendationsPain Manag Nurs201112423025022117755

- HerrKBjoroKDeckerSTools for assessment of pain in nonverbal older adults with dementia: a state-of-the-science reviewJ Pain Symptom Manag2006312170192

- AbbeyJPillerNDe BellisAThe Abbey pain scale: a 1-minute numerical indicator for people with end-stage dementiaInt J Palliat Nurs200410161314966439

- WardenVHurleyACVolicerLDevelopment and psychometric evaluation of the Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) ScaleJ Am Med Dir Assoc20034191512807591

- VillanuevaMRSmithTLEricksonJSLeeACSingerCMPain assessment for the dementing elderly (PADE): reliability and validity of a new measureJ Am Med Dir Assoc2003411812807590

- BogdukNEvidence-based clinical guidelines for the management of acute low back painAustralian faculty of musculoskeleltal medicine1999

- LateefHPatelDWhat is the role of imaging in acute low back pain?Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med200922697319468875