Abstract

Purpose

Chronic pain is a significant comorbidity in individuals with alcohol dependence (AD). Emotional processing deficits are a substantial component of both AD and chronic pain. The aim of this study was to analyze the interrelations between components of emotional intelligence and self-reported pain severity in AD patients.

Patients and methods

A sample of 103 participants was recruited from an alcohol treatment center in Warsaw, Poland. Information concerning pain level in the last 4 weeks, demographics, severity of current anxiety and depressive symptoms, as well as neuroticism was obtained. The study sample was divided into “mild or no pain” and “moderate or greater pain” groups.

Results

In the logistic regression model, across a set of sociodemographic, psychological, and clinical factors, higher emotion regulation and higher education predicted lower severity, whereas increased levels of anxiety predicted higher severity of self-reported pain during the previous 4 weeks. When the mediation models looking at the association between current severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms and pain severity with the mediating role of emotion regulation were tested, emotion regulation appeared to fully mediate the relationship between depression severity and pain, and partially the relationship between anxiety severity and pain.

Conclusion

The current findings extend previous results indicating that emotion regulation deficits are related to self-reported pain in AD subjects. Comprehensive strategies focusing on the improvement of mood regulation skills might be effective in the treatment of AD patients with comorbid pain symptoms.

Introduction

According to the American Society of Addiction Medicine, “dysfunctional emotional response,” along with cognitive function impairments, is a key feature of addiction. Deficits in emotional processing including emotion recognition, labeling,Citation1,Citation2 and alexithymiaCitation3 have been reported in various alcohol-dependent (AD) samples. Difficulties in the identification and description of one’s own emotional state, together with impairments in perception and labeling of emotion displayed by others, may represent a complex emotion-processing deficit in this clinical group. The aforementioned competencies are implied as one of the basic constituents of emotional intelligence (EI). EI has been definedCitation4 as a compound of emotional skills or traits that includes: “the ability to perceive accurately, appraise, and express emotion; the ability to access and/or generate feelings when they facilitate thought; the ability to understand emotion and emotional knowledge; and the ability to regulate emotions to promote emotional and intellectual growth”. Preliminary data suggest that individuals with AD also have lower EI; however, there is still not enough clinical data coming from AD population to make unequivocal conclusions.Citation5,Citation6 Of importance, limited data show that emotion-processing deficits may be associated with adverse outcomes in AD samples. Deficits in utilization of emotions predicted poorer post-treatment outcomes in a recent study of those treated for AD.Citation7 In another study, poor emotion-regulation skills in AD samples predicted post-treatment alcohol use at 3-month follow-up.Citation8

Pain is commonly comorbid with alcohol use disorders (AUDs).Citation9,Citation10 National surveys have revealed that AD is approximately twice as likely to occur among individuals with chronic pain.Citation9,Citation10 In clinical samples, more than 40% of patients treated for chronic pain met criteria for an AUD.Citation11 Conversely, between 18% and 38% of patients who participated in various addiction treatment programs in the USA reported at least moderately severe pain in the last 12 months.Citation12 Despite the importance of understanding the intersection between pain and alcohol use, only limited work has been carried out in this area and most of this has been done from a neurobiological perspective. Of clinical importance, pain is a predictor of poor drug- and alcohol-related outcomes in those treated for addictive disorders, including AUDs,Citation12,Citation13 and self-reported decrease in pain following treatment for AD is associated with a lower risk of alcohol relapse.Citation14

Several explanations for the prevalent co-occurrence of AUD and chronic pain have been proposed. It has been postulated that comorbidity of pain and AUD may be explained by recursive, partly shared, neural systems. In this context, pain is conceptualized as a disorder of reward functionCitation15 sharing pathophysiological mechanisms with addictions.Citation16 Biologically, a strong evidence of overlapping neurocircuitry, underlying pain and addiction, led Egli et alCitation17 to argue that AUD could be conceptualized as either a chronic pain disorder or a type of chronic emotional pain syndrome (p. 449).Citation18

Among the psychological mechanisms that influence pain,Citation19 a significant role for emotional processes has been affirmed.Citation20–Citation22 It is acknowledged that pain can be derived solely from emotional or social sources in the absence of nociception.Citation16 Neurobiological data indicate reciprocal interactions between pain and emotions.Citation23,Citation24 Numerous studies highlight interactions between pain and stress, pain and negative affect, pain and alexithymia, and broadly defined emotional regulation processes and pain.Citation21,Citation24,Citation25 Such studies also demonstrate the modulating effect of negative emotions on pain intensity.Citation26–Citation29 Moreover, chronic pain can elicit ineffective coping strategies and physical and psychosocial disability, leading to reduced quality of lifeCitation30 and depressive or anxiety symptoms. It has been consistently reported that more than 50% of chronic pain patients also manifest clinical symptoms of depression.Citation31,Citation32 Wiech and TraceyCitation33 noted that the relationship between pain and emotions is bidirectional, in that the experiential component of pain aggravates concurrent negative emotions, which then fuels the experience of pain. Studies suggest that individual differences in emotional regulation intervene in this relationship. In a sample of women with rheumatoid arthritis, Hamilton et alCitation34 found that self-reported pain severity varied as a function of emotional intensity and regulation. Women who reported higher emotional intensity and lower ability to regulate their emotions suffered more after a week of increased pain. Likewise, Connelly et alCitation35 found that variability in regulating positive and negative affect was associated with the pain severity in a group of subjects with rheumatoid arthritis. Within the EI framework, Ruiz-Aranda et alCitation36 showed that healthy women, who rated themselves as being more skilled in “emotional repair” (i.e., the ability to use positive thinking to repair negative mood), perceived a standard pain stimulus – induced via the cold-pressor experimental paradigm (CPT) – as less painful than did women who self-reported lower skills. In another study from this group,Citation37 participants with higher behaviorally measured EI scores rated pain as both less intense and unpleasant.

Together, the current literature shows that emotional processing deficits are common in both AD and chronic pain, and may lead to significant adverse outcomes in AD subjects. Moreover, recent data reveal that the two might share a common neurobiological background.Citation38 As suggested by LeBlanc et alCitation38 chronic pain and nociceptive hypersensitivity may induce alcohol craving and relapse through alterations in synaptic plasticity within brain reinforcement circuitry. The authors further suggest that pain-induced affective dysregulation in vulnerable individuals may contribute to the transition to addiction. Accordingly, clinical data show that pain syndromes are most commonly diagnosed among psychiatric patients, when reward alterations are also noted.Citation15 To the best of our knowledge, there are no data on the relationship between EI and pain severity in a clinical sample of AD individuals. Hence, the purpose of the present study was to explore the relationship between components of EI and self-reported pain severity in AD patients. We also examined whether EI components mediate the relationship between components of negative affect (severity of depression and anxiety) and self-reported pain. We anticipated that EI would make an independent contribution to the prediction of pain severity in this treatment sample.

Patients and methods

Participants

The study group comprised 103 alcohol-dependent patients entering an 8-week inpatient treatment program in Warsaw, Poland. The study assessments were performed within the first week since admission. Subjects with comorbid severe medical illness, receiving or requiring opioid analgesic therapy, as well as those currently receiving pharmacotherapy for AD, were not admitted to the inpatient treatment program. Similarly, individuals with comorbid psychiatric disorders requiring medication were not admitted to the treatment center. A current diagnosis of AD was established according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed, Text RevisionCitation39 criteria during admission and confirmed with the MINI International Neuropsychiatric InterviewCitation40 by a trained member of the research team. Confirmed abuse or dependence on psychoactive substances other than nicotine and alcohol was exclusionary. All individuals with significant cognitive deficits, scoring <25 on the Mini-Mental State Examination,Citation41 as well as patients with a history of psychosis or presence of alcohol withdrawal symptoms, were not eligible to participate.

The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee at the Medical University of Warsaw and the Medical School Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan. Written informed consent was obtained from all individuals who participated in the study.

Measures

Sociodemographic characteristics (education, marital status, and employment) were obtained using a modified version of the University of Arkansas Substance Abuse Outcomes Module, a self-administered questionnaire.Citation42 A single item from the Polish version of Short Form Health Survey (SF-36)Citation43 was included as a measure of physical pain during the past 4 weeks. The question that was asked was, “During the last 4 weeks, how much physical pain did you experience on average?,” with the possible responses: 1 – no pain, 2 – very mild pain, 3 – mild pain, 4 – moderate, 5 – strong, and 6 – very strong physical pain during the last 4 weeks. Consistent with prior work,Citation12,Citation44,Citation45 the responses 1–3 were subsequently re-coded into a categoric variable “mild or no pain,” and responses 4–6 into “moderate or greater pain.”

The subscale score for state anxiety from the brief symptom inventory,Citation46 depression severity,Citation47 and neuroticism (NEO Five-Factor Inventory)Citation48,Citation49 were included as a measures of negative affect.

The Schutte Self-Report Emotional Intelligence Test (SSEIT) was utilized as a measure of EI. The most consistently reported factor structure of SSEIT has four factors, which were applied in this study. Factors were calculated and named according to Saklofske et alCitation50 and matched those described by Petrides and FurnhamCitation51 as follows: appraisal of emotions, mood regulation/optimism, utilization of emotions, and social skills.

Statistical analysis

In the bivariate analyses, AD subjects dichotomized by the severity of pain (“mild or no pain” vs “moderate or greater pain”) were compared in terms of basic demographic characteristics as well as severity of depressive and anxiety symptoms, neuroticism, and EI components. Analyses of variance (ANOVAs) and chi-square tests tested for differences between the two pain-level groups for continuous and dichotomus variables, respectively. Subsequently, a logistic regression model was applied in order to determine the strongest independent correlates of physical pain in the current AD sample. To avoid multicollinearity between the affect-related risk factors (EI, depression, anxiety, and neuroticism), a correlation matrix was performed, and intercorrelation values above 0.7 between variables excluded them from further analyses. Controlling for age and gender, all variables that were significantly associated with pain severity in the bivariate analyses were included in the model.

Since it was hypothesized that individual differences in EI would serve as a mediator in the relationship between depression/anxiety and pain severity, two sets of mediation analyses were conducted: one with depression and the other with anxiety being the independent variables. Mediation was tested using the Preacher and Hayes’s bootstrapping method with 5,000 resamples with replacement. For this, the SPSS macro suggested by Preacher and Hayes was used. The criterion for statistical significance in all tests (two-tailed) was p<0.05. The data were analyzed using statistical package SPSS® 23.0 for Windows.

Results

The study comprised 80 men (77%) and 23 women (23%). Their mean (±SD) age was 43.57 (±11.47) years and mean education level was 12.07 (±2.82) years (the last level of secondary school in Poland). All patients were Caucasian.

ANOVAs looking at associations with self-reported pain levels revealed that patients with moderate/severe physical pain had higher neuroticism scores (F=6.79; p=0.01) and higher severity of depressive (F=5.35; p=0.02) and anxiety symptoms (F=10.93; p=0.001). Higher pain levels were also associated with lower education (F=6.38; p=0.01). By contrast, subjects who reported no/mild physical pain had higher scores in two of the four EI factors: self-reported mood regulation (F=9.60; p=0.003) and utilization of emotions (F=4.63; p=0.03). The detailed comparisons of individuals with moderate/severe physical pain and those with mild or no pain are presented in .

Table 1 Comparison of alcohol-dependent patients with moderate/severe and without or mild physical pain

All variables that were significantly associated with pain levels were entered into a logistic regression analysis. After controlling for age and gender, mood regulation (OR=0.83; 95% CI: 0.70–0.99; p=0.04), anxiety severity (OR=2.91; 95% CI: 1.11–7.62; p=0.03), and education (OR=0.76; 95% CI: 0.59–0.99; p=0.04) remained significant predictors of pain severity. The overall model was significant (chi-square=20.48, df=8, p=0.009) and explained 30% of the variance in pain severity ().

Table 2 Multivariate model of logistic regression analysis for the prediction of moderate/severe physical pain in alcohol-dependent patients

Mediation analyses

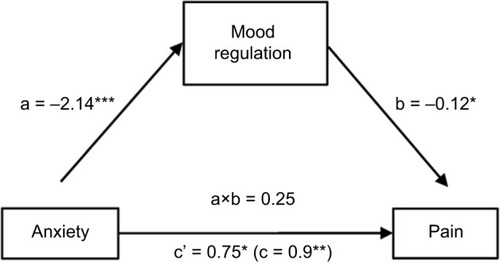

It was hypothesized that mood regulation would mediate the effect of both depression and anxiety on pain, thus two sets of mediation analyses were conducted. The first analysis revealed that the indirect effect of depression on pain through mood regulation was significant, with an unstandardized point estimate of 0.03 and a 95% CI of 0.002–0.08. Furthermore, the direct effect of depression on pain (0.05; SE=0.02; p<0.03) became nonsignificant when mood regulation was included as a mediator of the direct effect in the model (0.02; SE=0.03; p=0.52). Thus, mood regulation fully mediated the relationship between depression and pain ().

Figure 1 Mood regulation as a mediator of the relationship between depression and pain.

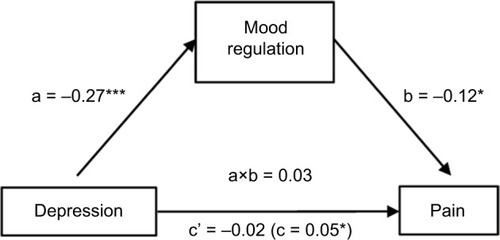

The second analysis yielded a significant indirect effect of anxiety on pain through mood regulation (0.25) with a 95% -confidence interval from 0.04 to 0.66. Mood regulation only partially mediated the anxiety–pain relationship, as anxiety still had a significant direct effect on pain (0.75; SE=0.32; p<0.02), albeit lower than without mood regulation being controlled for (0.89; SE=0.31; p<0.005) ().

Discussion

The purpose of our study was to examine how various components of self-reported EI relate to self-reported pain severity in AD individuals. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the association between self-reported EI and pain in this clinical population. The study results show that while controlling for negative affect and sociodemographic factors in AD patients, deficits in emotional regulation – a component of EI measured by the SSEIT scale – were a significant correlate of self-reported pain severity during the previous 4 weeks. Utilization of emotions was associated with pain severity before controlling for other variables, but the other two components of EI were not associated with pain. Anxiety and lower education – albeit not depression – were also associated with pain in the multivariate analysis. Education has consistently been shown to be a significant correlate of physical pain severity.Citation52–Citation55

The mood regulation factor in the SSEIT scale reflects a person’s ability to understand, recognize, and manage his/her feelings. It measures the capacity to maintain positive feelings on the basis of both previous experiences of doing so and the anticipation and involvement in activities that enhance positive feelings. The better their ability at mood regulation, the easier for individuals to acquire, maintain, and benefit from positive affect.

The study results also revealed that mood regulation fully mediated the relationship between depression and pain, and partially the relationship between anxiety and pain. In other words, greater levels of negative affect (depression or anxiety) were associated with worse emotional regulation skills and more pain. Our results suggest that the self-perceived ability to regulate emotions is a major contributor to the relationship between negative affect and pain. Negative affect may increase the perception of pain, and pain may increase negative affect, but their bidirectional effects depend on emotional regulation competencies in AD patients. These results are consistent with studies in healthy controls and chronic pain populations, focusing on the influence of the negative/positive emotions utilization skills in the pain–affect relationship.Citation35,Citation56–Citation60

The results of our study are in line with observations that emotional traits and abilities are associated with self-reported pain severity in chronic pain patients as well as pain-free participants.Citation34,Citation36,Citation37,Citation61 In addition, the results of the previous studies reveal that with the changing emotional state (negative or positive affect), pain sensitivity, and perception changes accordingly, depending on the valence of the emotion induced.Citation62,Citation63,Citation21 Studies on the effects of mood induction (positive, negative, or neutral) in pain-free participants show that the induction of negative mood results in a significant decrease in CPT pain tolerance, whereas the effect is reversed for the positive mood induction condition.Citation64 Importantly, increased positive affect weakens the association between negative affect and pain.Citation57–Citation60 This finding has been corroborated by longitudinal observations showing that pain reduction is predicted by increases in positive and decreases in negative affect.Citation35,Citation56 Conversely, pain can lead to long-lasting negative emotions, with the modulating effect of individual personality characteristics or previous reflection related to pain experience referred to as “secondary pain affect.”Citation65 Chronic “unspecific” pain may itself be considered a form of masked depression.Citation66 Through its relationship to aggravated depressive symptoms, pain increased the probability of depression recurrence.Citation67 Across studies, patients with chronic conditions (back pain, arthritis, fibromyalgia, and chronic widespread pain) generally have a two- to eight-fold greater likelihood of being diagnosed with a depressive disorder.Citation68 Meta-analytic data confirmed the pain-reducing properties of antidepressants (vs placebo) in chronic back pain patients.Citation69 Importantly, once a cycle of chronic or recurrent pain and negative affect (as in AD subjects) has developed, it might be difficult and clinically irrelevant to determine the current causal relationship between the two conditions.Citation33

Among the various emotional correlates of pain, significant attention is now being directed to the variably defined theoretical concept of emotion regulation. In a longitudinal study, Paquet et alCitation56 found that increased affect regulation was related to lower levels of pain intensity. Ruiz-Aranda et alCitation36 showed that pain-free women scoring high in the self-perceived ability to use positive thinking to repair negative mood, reported less sensory and affective pain during the CPT procedure. Importantly, once the experimental task was over, the negative impact of pain induction on mood was less severe in those scoring high in emotional repair. These results are consistent with the other studies showing that higher emotional repair is associated with lower perception of pain.Citation35,Citation56

Our results have clinical implications. Emotional dysregulation is a significant correlate of alcohol use disorders, even in the absence of chronic pain, and drinking alcohol is commonly used by patients as an ineffective self-medication strategy for both managing painCitation70 and coping with negative affect.Citation71 Growing research data suggest common underlying neurobiological mechanisms for chronic pain and addiction, including reward deficiency and antireward processes, incentive sensitization, and aberrant learning.Citation15 As noted by Navratilova and PorrecaCitation16 chronic pain is a constant challenge for relief and can suppress or surpass other emotions, including natural rewards, leading to negative affect and anhedonia (as a reflection of reward deficiency). These negative affective states supported with the pain-induced dysregulation of reward/reinforcement circuitry may lead to excessive substance use and possibly, for some vulnerable individuals, contribute to the development of addiction.Citation38

Recent preliminary findings revealed that deficits in utilizing and regulating emotions were an independent predictor of relapse in AD patients,Citation7 whereas chronic pain was shown to be associated with worse pain-related and substance-related outcomes among adults treated for substance use disorders.Citation13,Citation14,Citation72 These observations underlie the clinical significance of further studies on emotional competencies and pain in AD individuals. Given that 1) pain is a highly prevalent and problematic comorbidity in addiction treatment settings and 2) emotional regulation deficits are a significant correlate of both pain and AD, it is reasonable to develop and test therapeutic strategies to improve emotional skills in patients with this comorbidity. The efficacy of psychological interventions targeted at reducing pain and improving functioning in persons with a broad spectrum of pain-related conditions has been demonstrated.Citation73,Citation74 However, these treatments have not been well tested in those with AUDs. Mindfulness has been suggested as a potentially beneficial therapy for chronic pain,Citation74 and has also been used for relapse prevention in AD patients.Citation75 Our data suggest that affect regulation skills training might reduce negative affect and its effect on pain intensity.

The results of our study need to be interpreted with caution because of several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design of the study precludes any conclusions regarding causation and/or directionality of the revealed associations, specifically, whether higher depressive or anxiety severity leads to greater self-reported pain or the painful experience generates higher negative affect, with the mediating effect of emotion regulation. Our findings should be confirmed within the experimental design of longitudinal observations. Moreover, our single-item, self-report measure of pain intensity in the previous 4 weeks is unidimensional, albeit utilized in other studies.Citation12,Citation76,Citation77 It does not assess for the perceptual threshold, cause, location, or type of pain as well the specific context for its chronicity, origin, or continuation into the present. Except for the exclusionary criterion of opioid use, the data on the utilization of other pain management strategies such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or physical therapy, in the group of AD patients with moderate or greater pain, were not available. Finally, our study group was confined only to patients who entered inpatient treatment for AD, which may not be representative of the broader population of individuals with AD and comorbid pain syndromes.

Conclusion

The results of the current study extend previous findings and suggest that emotion regulation deficits are related to severity of self-reported pain in AD subjects. Comprehensive psycho-therapeutic interventions focusing on the improvement of mood regulation skills might improve the effectiveness of the treatment of AD patients with the comorbid pain symptoms.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Science Centre (2012/07/B/HS6/02370; principal investigator [PI]: M Wojnar), Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education (2P05D 004 29; PI: M Wojnar), and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R21 AA016104; PI: KJ Brower).

The preliminary results from this paper were presented at the 15th European Society for Biomedical Research on Alcoholism Congress, 12–15 November, 2015, Valencia, Spain, as a conference talk with interim findings. The abstract has been published.Citation78

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- CastellanoFBartoliFCrocamoCFacial emotion recognition in alcohol and substance use disorders: a meta-analysisNeurosci Biobehav Rev20155914715426546735

- DonadonMFOsorio FdeLRecognition of facial expressions by alcoholic patients: a systematic literature reviewNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat20141051655166325228806

- ThorbergFAYoungRMSullivanKALyversMAlexithymia and alcohol use disorders: a critical reviewAddict Behav200934323724519010601

- MayerJDSaloveyPWhat is emotional intelligence?SaloveyPSluyterDJEmotional Development and Emotional Intelligence: Educational ImplicationsNew York, NYBasic Books1997334

- PetersonKMalouffJThorsteinssonEBA meta-analytic investigation of emotional intelligence and alcohol involvementSubst Use Misuse201146141726173321995583

- KunBDemetrovicsZEmotional intelligence and addictions: a systematic reviewSubst Use Misuse2010457–81131116020441455

- KoperaMJakubczykASuszekHRelationship between emotional processing, drinking severity and relapse in adults treated for alcohol dependence in PolandAlcohol Alcohol201550217317925543129

- BerkingMMargrafMEbertDWuppermanPHofmannSGJunghannsKDeficits in emotion-regulation skills predict alcohol use during and after cognitive-behavioral therapy for alcohol dependenceJ Consult Clin Psychol201179330731821534653

- SubramaniamMVaingankarJAAbdinEChongSAPsychiatric morbidity in pain conditions: results from the Singapore Mental Health StudyPain Res Manag201318418519023936892

- Von KorffMCranePLaneMChronic spinal pain and physical-mental comorbidity in the United States: results from the national comorbidity survey replicationPain2005113333133915661441

- KatonWEganKMillerDChronic pain: lifetime psychiatric diagnoses and family historyAm J Psychiatry198514210115611604037126

- PotterJSPratherKWeissRDPhysical pain and associated clinical characteristics in treatment-seeking patients in four substance use disorder treatment modalitiesAm J Addict200817212112518393055

- CaldeiroRMMalteCACalsynDAThe association of persistent pain with out-patient addiction treatment outcomes and service utilizationAddiction2008103121996200518855809

- JakubczykAIlgenMAKoperaMReductions in physical pain predict lower risk of relapse following alcohol treatmentDrug Alcohol Depend2016158116717126653340

- ElmanIBorsookDCommon brain mechanisms of chronic pain and addictionNeuron2016891113626748087

- NavratilovaEPorrecaFReward and motivation in pain and pain reliefNat Neurosci201417101304131225254980

- EgliMKoobGFEdwardsSAlcohol dependence as a chronic pain disorderNeurosci Biobehav Rev201236102179219222975446

- KoobGFLe MoalMNeurobiology of AddictionAmsterdam; BostonElsevier Academic2006

- PriceDDPsychological Mechanisms of Pain and AnalgesiaSeattle, WAIASP Press1999

- de WiedMVerbatenMNAffective pictures processing, attention, and pain tolerancePain2001901–216317211166983

- KeefeFJLumleyMAndersonTLynchTStudtsJLCarsonKLPain and emotion: new research directionsJ Clin Psychol200157458760711255208

- VillemureCSlotnickBMBushnellMCEffects of odors on pain perception: deciphering the roles of emotion and attentionPain20031061–210110814581116

- StrobelCHuntSSullivanRSunJSahPEmotional regulation of pain: the role of noradrenaline in the amygdalaSci China Life Sci201457438439024643418

- LumleyMACohenJLBorszczGSPain and emotion: a biopsychosocial review of recent researchJ Clin Psychol201167994296821647882

- SullivanMJThornBRodgersWWardLCPath model of psychological antecedents to pain experience: experimental and clinical findingsClin J Pain200420316417315100592

- BishopMDCraggsJGHornMEGeorgeSZRobinsonMERelationship of intersession variation in negative pain-related affect and responses to thermally-evoked painJ Pain201011217217819853524

- FernandezEMilburnTWSensory and affective predictors of overall pain and emotions associated with affective painClin J Pain1994101398193443

- FernandezETurkDCDemand characteristics underlying differential ratings of sensory versus affective components of painJ Behav Med19941743753907966259

- FurlongLVZautraAPuenteCPLopez-LopezAValeroPBCognitive-affective assets and vulnerabilities: two factors influencing adaptation to fibromyalgiaPsychol Health201025219721220391215

- SmithBHElliottAMChambersWASmithWCHannafordPCPennyKThe impact of chronic pain in the communityFam Pract200118329229911356737

- DworkinRHGitlinMJClinical aspects of depression in chronic pain patientsClin J Pain19917279941809423

- BairMJRobinsonRLKatonWKroenkeKDepression and pain comorbidity: a literature reviewArch Intern Med2003163202433244514609780

- WiechKTraceyIThe influence of negative emotions on pain: behavioral effects and neural mechanismsNeuroimage200947398799419481610

- HamiltonNAZautraAJReichJIndividual differences in emotional processing and reactivity to pain among older women with rheumatoid arthritisClin J Pain200723216517217237666

- ConnellyMKeefeFJAffleckGLumleyMAAndersonTWatersSEffects of day-to-day affect regulation on the pain experience of patients with rheumatoid arthritisPain20071311–216217017321049

- Ruiz-ArandaDSalgueroJMFernandez-BerrocalPEmotional regulation and acute pain perception in womenJ Pain201011656456920015703

- Ruiz-ArandaDSalgueroJMFernandez-BerrocalPEmotional intelligence and acute pain: the mediating effect of negative affectJ Pain201112111190119621865092

- LeBlancDMMcGinnMAItogaCAEdwardsSThe affective dimension of pain as a risk factor for drug and alcohol addictionAlcohol201549880380926008713

- APA Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders4th ed, Text RevisionWashington, DCAmerican Psychiatric Association2000

- SheehanDVLecrubierYSheehanKHThe Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10J Clin Psychiatry199859Suppl 20S22S33

- FolsteinMFFolsteinSEMcHughPR“Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinicianJ Psychiatr Res19751231891981202204

- SmithGERossRLRostKMPsychiatric outcomes module: substance abuse outcomes module (SAOM)SedererLIDickeyBOutcome Assessment in Clinical PracticeBaltimore, MDWilliams and Wilkins19968588

- Zołnierczyk-ZredaDPolska wersja kwestionariusza SF-36v2 do badania jakości życia [The Polish version of the SF-36v2 questionnaire for the quality of life assessment]Przegl Lek2010671213021307 Polish21591357

- RosenblumAJosephHFongCKipnisSClelandCPortenoyRKPrevalence and characteristics of chronic pain among chemically dependent patients in methadone maintenance and residential treatment facilitiesJAMA2003289182370237812746360

- TraftonJAOlivaEMHorstDAMinkelJDHumphreysKTreatment needs associated with pain in substance use disorder patients: implications for concurrent treatmentDrug Alcohol Depend2004731233114687956

- DerogatisLRMelisaratosNThe brief symptom inventory: an introductory reportPsychol Med19831335956056622612

- BeckATSteerRABrownGBrown manual for the beck depression inventory IISan Antonio, TXPsychological Corporation1996

- CostaPMcCraeRRNEO PI-R Professional manualOdessa, FLPsychological Assessment Resources1992

- ZawadzkiBSJSzczepaniakPŚliwińskaMInwentarz Osobowości NEO-FFI Costy i McCrae. Podręcznik do polskiej adaptacjiWarszawaPracownia Testów Psychologicznych PTP1998

- SaklofskeDHAustinEJMinskiPSFactor structure and validity of a trait emotional intelligence measurePers Individ Dif2003344707721

- PetridesKVFurnhamAOn the dimensional structure of emotional intelligencePers Individ Dif2000292313320

- CastilloRCMacKenzieEJWegenerSTBosseMJPrevalence of chronic pain seven years following limb threatening lower extremity traumaPain2006124332132916781066

- DemyttenaereKBonnewynABruffaertsRBrughaTDe GraafRAlonsoJComorbid painful physical symptoms and depression: prevalence, work loss, and help seekingJ Affect Disord2006922–318519316516977

- TsangAVon KorffMLeeSCommon chronic pain conditions in developed and developing countries: gender and age differences and comorbidity with depression-anxiety disordersJ Pain200891088389118602869

- JakubczykAIlgenMABohnertASPhysical Pain in Alcohol-Dependent Patients Entering Treatment in Poland-Prevalence and CorrelatesJ Stud Alcohol Drugs201576460761426098037

- PaquetCKergoatMJDubeLThe role of everyday emotion regulation on pain in hospitalized elderly: insights from a prospective within-day assessmentPain2005115335536315911162

- StrandEBZautraAJThoresenMOdegardSUhligTFinsetAPositive affect as a factor of resilience in the pain-negative affect relationship in patients with rheumatoid arthritisJ Psychosom Res200660547748416650588

- ZautraASmithBAffleckGTennenHExaminations of chronic pain and affect relationships: applications of a dynamic model of affectJ Consult Clin Psychol200169578679511680555

- ZautraAJJohnsonLMDavisMCPositive affect as a source of resilience for women in chronic painJ Consult Clin Psychol200573221222015796628

- DavisMCZautraAJSmithBWChronic pain, stress, and the dynamics of affective differentiationJ Pers20047261133115915509279

- HamiltonNAZautraAJReichJWAffect and pain in rheumatoid arthritis: do individual differences in affective regulation and affective intensity predict emotional recovery from pain?Ann Behav Med200529321622415946116

- LoggiaMLMogilJSBushnellMCExperimentally induced mood changes preferentially affect pain unpleasantnessJ Pain20089978479118538637

- WeisenbergMRazTHenerTThe influence of film-induced mood on pain perceptionPain19987633653759718255

- ZelmanDCHowlandEWNicholsSNCleelandCSThe effects of induced mood on laboratory painPain19914611051111896201

- PriceDDPsychological and neural mechanisms of the affective dimension of painScience200028854721769177210846154

- BlumerDHeilbronnMChronic pain as a variant of depressive disease: the pain-prone disorderJ Nerv Ment Dis198217073814067086394

- GerritsMMvan OppenPLeoneSSvan MarwijkHWvan der HorstHEPenninxBWPain, not chronic disease, is associated with the recurrence of depressive and anxiety disordersBMC Psychiatry2014142518724965597

- EdwardsRRCahalanCMensingGSmithMHaythornthwaiteJAPain, catastrophizing, and depression in the rheumatic diseasesNat Rev Rheumatol20117421622421283147

- SalernoSMBrowningRJacksonJLThe effect of antidepressant treatment on chronic back pain: a meta-analysisArch Intern Med20021621192411784215

- RileyJL3rdKingCSelf-report of alcohol use for pain in a multi-ethnic community sampleJ Pain200910994495219712901

- KhantzianEJThe self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: a reconsideration and recent applicationsHarv Rev Psychiatry1997452312449385000

- LarsonMJPaasche-OrlowMChengDMLloyd-TravagliniCSaitzRSametJHPersistent pain is associated with substance use after detoxification: a prospective cohort analysisAddiction2007102575276017506152

- KaiserRSMoorevilleMKannanKPsychological Interventions for the Management of Chronic Pain: a Review of Current EvidenceCurr Pain Headache Rep20151994326209170

- McCrackenLMVowlesKEAcceptance and commitment therapy and mindfulness for chronic pain: model, process, and progressAm Psychol201469217818724547803

- WitkiewitzKMarlattABehavioral therapy across the spectrumAlcohol Res Health201133431331923580016

- WitkiewitzKMcCallionEVowlesKEAssociation between physical pain and alcohol treatment outcomes: the mediating role of negative affectJ Consult Clin Psychol20158361044105726098375

- WitkiewitzKVowlesKEMcCallionEFroheTKirouacMMaistoSAPain as a predictor of heavy drinking and any drinking lapses in the COMBINE study and the UK Alcohol Treatment TrialAddiction201511081262127125919978

- KoperaMSuszekHJakubczykASY06, from negative affectivity to harmful behaviors – emotional processing in alcohol dependence; SY06-1, relationship between emotional intelligence and physical pain in alcohol-dependent patients entering treatment in PolandAlcohol Alcohol201550Suppl 1i7