Abstract

Purpose

To describe the efficacy and safety of hydromorphone extended-release tablets (OROS hydromorphone ER) during dose conversion and titration.

Patients and methods

A total of 459 opioid-tolerant adults with chronic moderate to severe low back pain participated in an open-label, 2- to 4-week conversion/titration phase of a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized withdrawal trial, conducted at 70 centers in the United States. Patients were converted to once-daily OROS hydromorphone ER at 75% of the equianalgesic dose of their prior total daily opioid dose (5:1 conversion ratio), and titrated as frequently as every 3 days to a maximum dose of 64 mg/day. The primary outcome measure was change in pain intensity numeric rating scale; additional assessments included the Patient Global Assessment and the Roland–Morris Disability Questionnaire scores. Safety assessments were performed at each visit and consisted of recording and monitoring all adverse events (AEs) and serious AEs.

Results

Mean (standard deviation) final daily dose of OROS hydromorphone ER was 37.5 (17.8) mg. Mean (standard error of the mean [SEM]) numeric rating scale scores decreased from 6.6 (0.1) at screening to 4.3 (0.1) at the final titration visit (mean [SEM] change, −2.3 [0.1], representing a 34.8% reduction). Mean (SEM) change in Patient Global Assessment was −0.6 (0.1), and mean change (SEM) in the Roland–Morris Disability Questionnaire was −2.8 (0.3). Patients achieving a stable dose showed greater improvement than patients who discontinued during titration for each of these measures (P < 0.001). Almost 80% of patients achieving a stable dose (213/268) had a ≥30% reduction in pain. Commonly reported AEs were constipation (15.4%), nausea (11.9%), somnolence (8.7%), headache (7.8%), and vomiting (6.5%); 13.0% discontinued from the study due to AEs.

Conclusion

The majority of opioid-tolerant patients with chronic low back pain were successfully converted to effective doses of OROS hydromorphone ER within 2 to 4 weeks.

Introduction

Approximately 14% of the United States population suffers from chronic pain resulting from a widespread collection of etiologies.Citation1,Citation2 Pain is often an undertreated condition despite various treatment options and increased recognition of its impact on patients’ quality of life.Citation3–Citation5 Opioid analgesics are frequently prescribed for patients with moderate to severe pain.Citation6,Citation7 Around-the-clock opioid therapy with an extended-release (ER) formulation may benefit individuals requiring prolonged analgesia.

Drug plasma levels induced by ER opioids are more stable than immediate-release (IR) formulations, and plasma levels can remain within the therapeutic range for extended periods of time.Citation8,Citation9 These pharmacokinetic characteristics of ER opioids translate into clinical advantages for the patient, such as sustained analgesia and decreased incidence of certain adverse reactions.Citation10–Citation12 Patients may also experience more restorative sleep, which may decrease subsequent pain.Citation13–Citation15 Less frequent dosing regimens typical of ER opioids may offer greater convenience to patients, potentially increasing compliance to the treatment regimen.Citation16,Citation17 Decreasing the overall pill burden is attractive to patients with chronic pain, who are often taking a number of concomitant medications to manage other conditions.Citation18

Opioids commonly used in the management of chronic pain include fentanyl, hydrocodone, hydromorphone, morphine, oxycodone, and oxymorphone.Citation19–Citation28 Adverse reactions commonly associated with opioid analgesics include constipation, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and somnolence.Citation7,Citation29,Citation30 Gastrointestinal (GI)-related adverse reactions are of particular concern, especially constipation, which is reported by over 40% of patients treated with strong opioids and is a common reason for discontinuing opioid therapy.Citation7,Citation29,Citation31 Recently published treatment guidelines suggest stool softeners, laxatives, and increased intake of fluids and fiber as prophylactic treatment prior to initiating opioid therapy.Citation7

Hydromorphone, a semisynthetic mu-opioid agonist, has been widely used in the management of pain for over 80 years and is currently available in both IR and ER formulations.Citation32 Compared with hydromorphone IR, once-daily hydromorphone ER tablets provide consistent drug plasma concentrations over 24 hours once a steady state has been achieved, with less peak-to-trough fluctuation.Citation10,Citation33 Hydromorphone is released at a controlled rate through an oral osmotic drug delivery system (OROS® Push-Pull™; Alza Corporation, Mountain View, CA, USA), which permits the once-daily dosing regimen.Citation34,Citation35 OROS hydromorphone ER is highly potent, with a 5:1 equianalgesic ratio to morphine,Citation36–Citation43 and exhibits a tolerability profile consistent with other strong opioid analgesics.Citation44 The efficacy and safety of OROS hydromorphone ER has been established in both short- and long-term controlled trials in patients with chronic cancer and noncancer pain (including chronic low back pain [LBP], musculoskeletal pain, neuropathic pain, and other chronic pain conditions).Citation42,Citation43,Citation45–Citation47

Because patients exhibit variability in sensitivity to different opioids,Citation7,Citation48,Citation49 clinicians often need to try several options before finding an agent that provides effective analgesia at a tolerable dose. In a retrospective chart review of patients with chronic noncancer pain, 36% of patients achieved an effective and tolerable dose of the first opioid prescription given; however, 45% required between two and five opioid trials to achieve a stable, effective opioid regimen.Citation50 Whether early in the treatment process or after a period of chronic treatment when efficacy declines or adverse events (AEs) increase in response to dose escalation, many patients receiving long-term opioid therapy are likely to require rotation from one agent to another at some point.Citation51 It is therefore essential for clinicians to understand the dosing parameters for converting patients from prior opioid therapy to any new opioid agent or formulation, as well as the expected safety and efficacy profile during dose titration.

A multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in patients with chronic moderate to severe LBP showed that OROS hydromorphone ER was effective and well tolerated.Citation41 Results from the double-blind phase of the study showed that the reduction in pain intensity was maintained over 12 weeks with continued use of OROS hydromorphone ER, and that this was significantly superior to placebo.Citation41 Reported here are the efficacy and safety data obtained during the open-label conversion and titration phase of this trial, which reflects usual clinical practice and may provide useful insights for clinicians incorporating OROS hydromorphone ER into opioid rotation programs for patients on chronic opioid therapy.

Methods

Study design

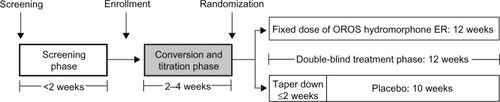

This was the open-label conversion and titration phase of a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized withdrawal study of OROS hydromorphone ER in patients with chronic LBP (). The conversion and titration phase lasted 2 to 4 weeks and consisted of up to five visits. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards at all centers and performed in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines. All patients gave written informed consent prior to undergoing any study procedure.

Patients

Study patients were 18 to 75 years of age and had moderate to severe chronic LBP for at least 20 days per month, for a minimum of 3 hours per day, for at least 6 months. Patients were required to have: (1) non-neuropathic (Class 1 and 2) or neuropathic (Class 3, 4, 5, or 6) LBP based on the Quebec Task Force Classification of Spinal Disorders; and (2) a daily opioid requirement of ≥60 mg oral morphine equivalent (≥12 mg of hydromorphone), but ≤320 mg oral morphine equivalent (≤64 mg hydromorphone) per day within the 2 months prior to the screening visit.

Exclusion criteria included: (1) an allergic reaction or hypersensitivity to opioids; (2) an active diagnosis of fibromyalgia, complex regional pain syndrome, acute spinal cord compression, back pain because of a secondary tumor, or pain caused by a confirmed or suspected neoplasm; (3) having undergone a surgical procedure for back pain within 6 months prior to the screening visit; (4) nerve or plexus block, including epidural steroid injections or facet blocks within 1 month prior to screening; or (5) preexisting severe narrowing of the GI tract secondary to prior GI surgery or GI disease resulting in impaired GI function.

Eligible patients were entered into the screening phase and trained on how to record their average pain in the past 24 hours in pain diaries every evening between 7:00 pm and 11:59 pm. Patients were required to document their daily pain intensity for two consecutive practice days using an eleven-point numeric rating scale (NRS), where 0 indicated no pain and 10 indicated the worst possible pain. Patients who met entrance requirements and enrolled in the study returned to the clinic within 14 days to begin the conversion and titration phase.

Dosing schedule and stabilization

During conversion, patients were converted to a dosage of OROS hydromorphone ER (Exalgo®; Mallinckrodt Brand Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Hazelwood, MO, USA) that was approximately 75% of the equianalgesic dose of their prior total daily opioid dose. Morphine conversion tables were used and assumed a morphine equivalent:hydromorphone potency ratio of 5:1. The lowest starting dose of OROS hydromorphone ER was 12 mg/day and the highest was 48 mg/day. OROS hydromorphone ER tablets, titrated to response and tolerability for each individual, were administered orally once daily in total daily doses of 12 mg, 16 mg, 24 mg, 32 mg, 40 mg, 48 mg, or 64 mg.

Titration was determined by daily pain intensity NRS scores and occurrence of AEs. OROS hydromorphone ER dosage could be titrated upward as frequently as every 3 days to the next available dosage (16 mg/day, 24 mg/day, 32 mg/day, 40 mg/day, 48 mg/day, or 64 mg/day of OROS hydromorphone ER) and twice per week. Only one dosage adjustment by telephone was allowed between each weekly visit. Decreases in OROS hydromorphone ER dosage were permitted only once, and not to below 12 mg/day. Dosages were not to exceed 64 mg/day during the course of the study. If the mean pain intensity NRS score during the last seven consecutive days (between visits) was ≤4 and the patient met stable dosing criteria within the 4-week timeframe, the patient was entered into the double-blind phase of the study.

Entry criteria into the double-blind phase included the following: final titrated doses of OROS hydromorphone ER that were ≥12 mg/day and ≤64 mg/day; patients were on the same dose without change for ≥7 consecutive days (stable dose period) and required a mean of ≤2 tablets of rescue medication per day; patients answered “yes” to the question, “Has this medication helped your pain enough so that you would continue to take the medication?”; and patients were free of adverse effects that were intolerable or that could impact their ability to complete the study. The final visit in the conversion and titration phase was considered the baseline visit of the double-blind phase for patients reaching stable doses and the termination visit for those who did not.

Efficacy analyses

The primary efficacy variable was the change in pain intensity NRS, recorded daily in patients’ diaries, from baseline to the final visit of the conversion and titration phase. The proportion of patients with 30% and 50% reductions in pain from screening to the final visit were calculated.Citation52 Reduction in pain was calculated as: (reduction in pain intensity from screening to final visit/pain intensity at screening) × 100.

Additional efficacy assessments included mean changes from baseline in Patient Global Assessment (PGA) scores, providing patients’ overall impression of the study drug based on a five-point scale (1 = excellent, 2 = very good, 3 = good, 4 = fair, 5 = poor), as well as the Roland–Morris Disability Questionnaire (RDQ). The RDQ is a 24-item questionnaire used to evaluate patients’ ability to perform routine tasks, with scores ranging from 0 (highest ability) to 24 (lowest ability).

Safety analyses

The Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS), consisting of eleven questions to assess patients’ withdrawal symptoms, was completed at all visits by the investigators. Total scores range from 0 to 48, with higher scores indicating more severe withdrawal symptoms, and are grouped as mild (5–12), moderate (13–24), moderately severe (25–36), and severe (>36).Citation53 Investigators determined if symptoms were attributed to an etiology other than opioid withdrawal. The Subjective Opiate Withdrawal Scale (SOWS), consisting of 16 questions to assess patients’ withdrawal symptoms, was also completed at all visits. Patients rated the degree to which they experienced each of the 16 symptoms (0 = not at all, 1 = a little, 2 = moderately, 3 = quite a bit, and 4 = extremely); total scores range from 0 to 64, with higher scores indicating more severe withdrawal symptoms.Citation54

Safety assessments were performed at each visit and consisted of recording and monitoring all AEs and serious AEs (SAEs). An SAE was considered any medical occurrence at any dose of study medication that resulted in death, was life threatening, required inpatient hospitalization or prolonged existing hospitalization, resulted in persistent or significant disability or incapacity, or was a congenital anomaly/birth defect. Treatment-emergent AEs were summarized by event intensity (mild, moderate, severe, or not reported) and relationship to study drug.

To prevent constipation, patients were permitted to use prophylaxis, such as osmotic laxatives (ie, lactulose, sorbitol) and peristalsis-increasing agents (ie, senna, bisacodyl).

Rescue medication use

Throughout the study, IR hydromorphone hydrochloride tablets (2 mg, 4 mg, and 8 mg) were used as rescue medication for breakthrough pain. IR hydromorphone tablet strength was determined as between 5% to 15% of an individual patient’s daily dose of OROS hydromorphone ER. Rescue medication use was unrestricted for the first 3 days, but was restricted to two tablets per day after day 3. Overuse of rescue medication did not subject patients to discontinuation prior to randomization in the double-blind phase of the study.

Statistical analyses

Prior opioids were coded using the World Health Organization encoding dictionary, and the numbers and percentages of patients receiving each opioid were summarized. The primary population for the efficacy analyses was the intent-to-treat population. Weekly NRS scores were calculated from daily patient diary entries, and a weekly mean change from baseline was calculated for each patient. For a patient’s mean pain score in a given week to be included in the analysis, there had to be at least one daily pain intensity NRS score in the patient’s diary for the week. If a patient discontinued due to opioid withdrawal symptoms, the baseline pain intensity NRS score was carried forward to the final visit. For those who discontinued due to an AE, the pain intensity score at screening was carried forward to the final visit. If a patient discontinued due to lack of efficacy or other reasons (eg, administrative, withdrawal of consent), the last observation (mean pain score over the last week in the study), was carried forward to the final visit (last observation carried forward). Descriptive statistics for PGA and RDQ scores are presented by treatment group at each visit, and for changes from baseline at each visit.

Total scores were calculated for COWS and SOWS by visit. The scales were imputed with the mean of nonmissing items if up to 25% of the items in the scale were missing. Missing items on a scale were imputed using last observation carried forward methodology. The total scores at each visit and change from screening at each visit were summarized using descriptive statistics and stabilized OROS hydromorphone ER dose.

The mean number of rescue medication tablets used per day was compared for patients reaching stable doses of OROS hydromorphone during conversion and titration and those who discontinued using a t-test with unequal variances.

Results

Patients

Of the 806 patients screened for study entry, 459 met the inclusion criteria and were enrolled into the conversion and titration phase. The safety population included 447 patients who received ≥1 dose of OROS hydromorphone ER. Overall, 179 patients discontinued during the conversion and titration phase after receiving OROS hydromorphone (at 75% equianalgesic dose of their prior opioid), most commonly due to AEs (13.0%, 58 patients) and a lack of analgesic efficacy (12.5%, 56 patients).

The mean (standard deviation [SD]) age of patients in the safety population was 49.0 (10.43) years, and 6.0% of patients were ≥65 years of age. About half of the patients were male, and the majority were Caucasian (). Patients entered the trial with moderate to severe pain as indicated by a mean (SD) NRS score of 6.6 (1.8). Prior opioid medications included hydrocodone, oxycodone, morphine, fentanyl, methadone, tramadol, propoxyphene, hydromorphone, and oxymorphone.

Table 1 Demographic and baseline characteristics

Conversion and titration

Sixty percent (n = 268) of patients successfully reached a stabilized dose of OROS hydromorphone ER within 4 weeks of screening. With the exception of patients previously receiving oxymorphone, there was a ≥50% success rate in conversion to OROS hydromorphone ER from all prior opioids (). The mean (SD) duration of exposure to OROS hydromorphone ER was 20.1 (9.58) days in the overall safety population (). Patients achieving a stable dose during conversion and titration had a mean (SD) duration of exposure of 23.4 (7.84) days (range, 8 to 47 days), versus 15.2 (9.84) days (range, 1–49 days) in patients discontinuing during titration. The total number of titration visits did not appear to influence patients’ ability to achieve a stabilized dose of OROS hydromorphone ER.

Table 2 Patients with response by prior opioid compound

Table 3 Duration of exposure

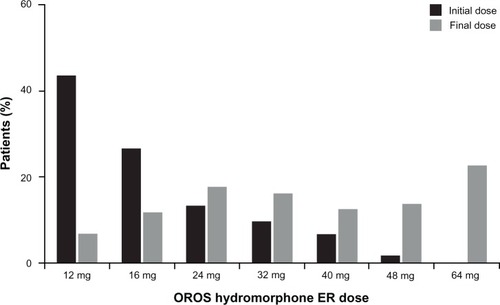

Approximately 43% of patients began the conversion and titration phase at a 12 mg dose of OROS hydromorphone ER, and the most common final daily dose was 64 mg (22.1%). The mean (SD) final dose of OROS hydromorphone ER was 37.5 (17.8) mg in the overall patient population, and was similar in patients reaching a stabilized dose or discontinuing during titration (37.8 [17.5] mg and 37.1 [18.2] mg, respectively). The distribution of initial and final doses of OROS hydromorphone ER in patients reaching a stabilized dose is shown in ; the final titration dose was 16 mg or higher for 94% of patients achieving a stabilized dose, and 32 mg or higher for 65% of patients.

Efficacy

In the overall population, mean (standard error of the mean [SEM]) NRS score decreased from 6.6 (0.1) at screening to 4.3 (0.1) at the final visit of the conversion and titration phase (mean [SEM] change from screening to final visit, −2.3 [0.1]), representing a 34.8% reduction. Likewise, mean (SEM) PGA score improved from 3.6 (0.04) at visit 1 to 3.0 (0.05) at the final visit (overall mean [SEM] change, −0.6 [0.1]), and mean (SEM) RDQ scores showed an improvement from 14.0 (0.2) at screening to 11.2 (0.3) at the final visit (mean change [SEM], −2.8 [0.3]).

When patients achieving a stable dose and patients discontinuing during titration were analyzed separately, those achieving a stable dose showed greater improvement. Mean (SEM) change in NRS score during the conversion and titration phase was −3.2 (0.1) for patients achieving a stable dose (representing a 50% reduction from screening) versus −0.7 (0.2) for dropouts during titration (P < 0.001). Mean (SEM) NRS score at baseline of the double-blind phase or termination visit was 3.3 (0.1) and 6.1 (0.2) in patients achieving a stable dose versus dropouts, respectively. The number of titration visits did not appear to influence the overall change in NRS score. The mean (SEM) PGA score decreased from 3.6 (0.1) to 2.5 (0.1) during the conversion and titration phase for patients achieving a stable dose, while increasing from 3.6 (0.1) at visit 1 to 3.8 (0.1) at the termination visit in patients discontinuing during titration (P < 0.001 for change from baseline in patients achieving a stable dose versus dropouts). Patients achieving a stable dose also had a mean (SEM) change in RDQ of −4.3 (0.3) [from 13.5 (0.3) at screening to 9.3 (0.4) at baseline of the double-blind phase], compared with a mean (SEM) change of −0.4 (0.3) for dropouts during titration (P < 0.001).

Almost 80% of patients (213/268) achieving a stable dose had a ≥30% reduction in pain, compared with 21.9% (37/179) of dropouts during titration. Among patients achieving a stable dose who had a ≥30% reduction in pain, 64.3% (137/213) were taking ≥32 mg of OROS hydromorphone ER. Approximately 52% of patients achieving a stable dose (140/268) had a ≥50% reduction in pain (among whom 64% [90/140] were taking a dose ≥ 32 mg), compared with 7.7% of dropouts during titration (13/179).

The mean number of rescue medication tablets per day was 2.7 during the first 3 days of conversion and titration, and ,1 tablet per day by the time a stable dose of OROS hydromorphone ER was achieved. The daily mean (SD) number of rescue medication tablets in patients achieving a stable dose and in those discontinuing during titration was 1.5 (0.89) and 2.4 (1.3), respectively (P < 0.001).

Opioid withdrawal symptoms

Mean (SD) COWS decreased from 1.0 (1.9) at visit 1 to 0.7 (1.4) at the final visit. The ability to achieve a stabilized dose or starting doses of OROS hydromorphone ER did not influence the mean change in COWS. Similar to COWS, SOWS decreased in the overall patient population from 7.2 (8.1) to 4.3 (6.1) from visit 1 to the final visit, respectively. In patients achieving a stable dose, mean (SD) change in SOWS from visit 1 to baseline of the double-blind phase was −3.5 (6.4). In contrast, the mean (SD) change in patients discontinuing during titration was −1.4 (8.3) from visit 1 to the termination visit.

Safety and tolerability

Approximately 55% of patients (n = 247) experienced ≥1 AE. The most commonly reported AEs were constipation, nausea, somnolence, headache, and vomiting, and were consistent among those who did or did not achieve a stable dose during titration (). About 5% of patients reported drug withdrawal syndrome. Of patients who reported AEs, the majority (90.6%) experienced AEs assessed with a maximum severity of mild or moderate (57.3% and 33.3%, respectively). Compared with dropouts during titration, those achieving a stable dose were less likely to report AEs (51.9% versus 60.3%, respectively).

Table 4 Most common adverse events in the safety population (>5%) overall and according to achievement of a stable dose

Aside from patient sex, baseline demographics such as age and race did not impact the incidence of AEs. Female patients, however, experienced more AEs than male patients (60.5% versus 50.2%), and reported constipation (18.2% versus 12.8%), nausea (15.5% versus 8.4%), and vomiting (9.5% versus 3.5%) more frequently.

In total, 13.0% of patients (n = 58) discontinued from the study due to an AE. A small percentage of patients (4.3%) withdrew due to GI disorders. Approximately 4% of patients withdrew due to nervous system disorders, such as somnolence (1.8%) and headache (1.6%). Most AEs that led to discontinuation were considered to be possibly or probably related to the study drug.

OROS hydromorphone ER dosage was reduced in 6.9% of patients. Approximately 2% of patients required dose reductions due to AEs. The incidence of AEs in relation to OROS hydromorphone ER dosage strength is presented in . The 24 mg dose of OROS hydromorphone ER was associated with the greatest incidence of AEs (30.2%).

Table 5 Summary of all AEs by OROS hydromorphone ER dose (safety population)

GI-related AEs

GI-related AEs, specifically constipation, nausea, and vomiting, were most commonly reported (30.4%). Incidence of GI-related AEs was similar between patients who achieved a stable dose and those who discontinued during titration (29.9% versus 31.3%, respectively), and was similar across all doses (12–48 mg) of OROS hydromorphone ER. Over 90% of GI-related AEs were considered mild or moderate in severity.

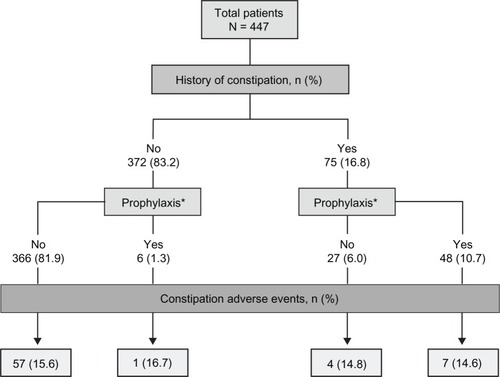

Constipation was reported by 69 patients (15.4%), 38 (8.5%) of whom received treatment for constipation during the conversion and titration phase. The incidence of constipation was similar in patients with or without a history of constipation (). In patients with a history of constipation, eleven (14.7%) reported an AE of worsening constipation. In patients without a history of constipation, 58 (15.6%) reported an AE of constipation. The incidence of constipation was similar in patients who were or were not treated prophylactically for constipation (14.8% versus 15.5%, respectively) prior to the conversion and titration phase.

Figure 3 Adverse events of constipation, by history of constipation and prophylaxis.

Abbreviations: N, total number; n, number.

Nineteen patients (4.3%) discontinued study participation because of GI-related AEs, most commonly due to nausea (1.8%), constipation (1.1%), and vomiting (0.9%). Additionally, gastritis and rectal hemorrhage each occurred in one patient (0.2%).

Treatment-related AEs and SAEs

Treatment-related AEs were reported by 43.0% of patients; 11.4% discontinued due to a treatment-related AE. The most commonly reported treatment-related AEs were constipation (14.3%), nausea (9.6%), somnolence (8.1%), headache (6.0%), and vomiting (4.5%). Five patients reported SAEs, none of which were determined by investigators to be related to OROS hydromorphone ER (). SAEs included meningitis, herpes, pneumonia, deep vein thrombosis, and diabetic ketoacidosis (one patient each). One patient experienced all of the following SAEs: hypokalemia, dizziness, nausea, and vomiting. No deaths occurred during the study.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to examine dosing parameters, efficacy, and safety in patients being converted to OROS hydromorphone ER from other ER opioid therapies. Results indicate that the majority of patients can be safely converted to OROS hydromorphone ER and titrated to effective doses within 2 to 4 weeks of treatment. The 5:1 morphine equivalent:hydromorphone conversion ratio used in this study is consistent with other published trials of OROS hydromorphone ER in patients with chronic cancer or non-cancer pain,Citation36–Citation43 supporting growing evidence for the use of this ratio in clinical practice. Although the 5:1 ratio indicates that hydromorphone ER is a potent opioid, it is important to note that the ratio is lower than the conversion ratio for oral hydromorphone IR, which has been reported to be as high as 8:1.Citation55

Patients included in the current study had previously received other strong opioids, such as other formulations of hydromorphone, fentanyl, hydrocodone, morphine, methadone, oxycodone, propoxyphene (no longer available), and oxymorphone. An analysis of conversion success according to prior opioid therapy revealed that the proportion of patients able to achieve a stable dose of hydromorphone ER did not depend to any appreciable extent on the specific opioid from which they were converting. This has clinical implications in the context of opioid rotation, which is often necessary for patients with chronic pain who experience a decline in therapeutic efficacy with their current opioid or inadequate efficacy or tolerability during conversion and titration of a new opioid therapy.Citation52 Results presented here lend additional support for the consideration of OROS hydromorphone ER as an appropriate option in well-selected patients rotating from any of the opioid therapies commonly used in clinical practice.

As reported previously, overall mean pain intensity was reduced by 50% with OROS hydromorphone ER treatment during the conversion and titration phase of this study, a reduction that was maintained in the active-treatment group during the 12-week double-blind phase.Citation41 When the current analysis of the conversion and titration phase reported results separately for patients who did or did not achieve a stable dose of hydromorphone ER, those who successfully converted to OROS hydromorphone ER from prior opioid therapy experienced significantly greater reductions in pain intensity, as well as improved functional abilities and treatment satisfaction.

Approximately 80% of patients achieving a stable dose of OROS hydromorphone ER experienced at least a 30% pain reduction, which meets an accepted threshold of clinically meaningful pain relief.Citation56,Citation57 Furthermore, 52% of patients in this group experienced a ≥50% pain reduction. These reductions were maintained over time, as 60.6% and 42.4% of patients showed ≥30% and ≥50% reductions in pain, respectively, at the end of the double-blind phase of the trial.Citation40

The safety profile of OROS hydromorphone ER is consistent with other strong (World Health Organization Step 3) opioids.Citation31 As expected, the most common AEs during conversion and titration were GI-related, as well as somnolence and headache. GI-related AEs, specifically constipation, warrant further attention. Overall incidence of constipation was approximately 15%, which is substantially lower than what was reported in a systematic review of strong opioids (41%).Citation31 The incidence of constipation did not vary according to a patient’s history of constipation or use of prophylactic medications, suggesting that OROS hydromorphone ER has a good GI tolerability profile under a variety of conditions. However, this study was not specifically designed to evaluate the true incidence of constipation or the effects of prophylactic or reactive management of constipation.

GI-related AEs were more common in female patients, as previously noted in the literature. Gender differences in AEs may be partially influenced by social factors that affect the way men and women communicate distress and perceive bodily experiences.Citation58 Other baseline characteristics, including age, did not appear to influence the incidence of AEs. There was no strong evidence for an increased incidence of AEs at higher doses, although the data should be interpreted with caution because the duration of exposure to each dose was not accounted for in the analysis. In the ten patients who required a dose reduction due to AEs, there was no apparent relationship between the AE and OROS hydromorphone ER dose. The lack of a dose-response relationship for AEs was likely due to the individualized dosing strategy employed in the conversion and titration phase, as dose-dependent AEs are more likely to be seen with fixed dosing.Citation59

There were no reports of abuse, overdose, or misuse during this trial. COWS and SOWS scores showed that most patients in the conversion and titration phase did not experience drug withdrawal, suggesting that the conversion and titration method used in this study was appropriate. It should be noted, however, that a small percentage of patients did report drug withdrawal syndrome as an AE.

This study had a number of limitations. Although the open-label, flexible-dose design of this phase of the study reflects usual clinical practice, there may have been factors in the design of this study that limited the ability of some patients to reach a stable dose of OROS hydromorphone ER. The time window for dose conversion and titration was limited to 2 to 4 weeks – a shorter time span than may be required in clinical practice to achieve an effective dose – and the maximum daily allowable dose of OROS hydromorphone ER was limited to 64 mg. The observation that 64 mg was the most common dose (taken by 22.1% of patients) at the final visit of the conversion and titration phase, and that 12.5% of patients discontinued due to lack of analgesic efficacy, suggests that the upper dose limit may not have been sufficient for a subset of patients. The mean final dose of OROS hydromorphone ER was approximately 38 mg/day in the conversion and titration phase of this study, which is lower than what has been reported in other studies of chronic noncancer and cancer pain (56.6 mg/day and 61.6 mg/day, respectively).Citation39,Citation40 In addition, the current study was performed in patients who were opioid-tolerant, and results may not be generalizable to opioid-naïve patients (it should be noted that OROS hydromorphone ER is indicated for use only in opioid-tolerant patientsCitation26). Conversion and titration of opioids should be implemented with particular caution in people without prior opioid exposure; medication should be initiated at a low dosage and titrated slowly to decrease the risk for adverse effects.Citation7

In conclusion, the detailed analysis of results from this conversion and titration phase confirm the findings of previous studies evaluating the efficacy and safety of OROS hydromorphone ER.Citation42,Citation43,Citation45–Citation47 Data collected during this phase emphasize the need for individual titration of each patient to a stabilized dose of OROS hydromorphone ER. OROS hydromorphone ER was associated with clinically meaningful reductions in pain in the majority of patients and was generally well tolerated. GI tolerability was good; the rate of GI-related AEs was low across doses, and most were considered mild or moderate in severity. These findings suggest that OROS hydromorphone ER is an appropriate option in an opioid rotation program for the management of chronic pain.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Neuromed Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Technical editorial and medical writing support for the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Amanda McGeary, Synchrony Medical Communications, LLC, West Chester, PA, USA. Funding for this support was provided by Mallinckrodt Inc, a Covidien company, Hazelwood, MO, USA.

Disclosure

Portions of these data were included in a poster presentation at PAINWeek 2011, September 7–10, 2011, Las Vegas, NV, USA.

Dr Hale discloses that he has served as a consultant or on an advisory board for Cephalon, Covidien, Neuromed, and Purdue Pharma, in addition to serving on speakers’ bureaus for Covidien and Purdue Pharma. Dr Nalamachu discloses that he has served as a consultant, on an advisory board, or on a speakers’ bureau for, and received honoraria from, Cephalon, Covidien, Endo Pharmaceuticals, Lilly, and ProStrakan. In addition, Dr Nalamachu has received research grants from Covidien, Endo Pharmaceuticals, and ProStrakan. Dr Khan and Mr Kutch do not have conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- United States Census BureauPreliminary annual estimates of the resident population for the United States, regions, states, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2010 (NST-PEST2010-01) [webpage on the Internet]2002 [updated Feb 2011]Washington, DCUnited States Census Bureau Available from: http://www.census.gov/popest/research/eval-estimates/eval-est2010.htmlAccessed October 22, 2012

- National Center for Health StatisticsHealth, United States, 2006. With Chartbook on Trends in the Health of AmericansHyattsville, MDNational Center for Health Statistics2006 DHS Publication No 2006-1232. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus06.pdfAccessed March 8, 2012

- HaanpääMLBackonjaMMBennettMIAssessment of neuropathic pain in primary careAm J Med2009122Suppl 10S13S2119801048

- KhouzamRHChronic pain and its management in primary careSouth Med J2000931094695211147475

- McCarbergBHPain management in primary care: strategies to mitigate opioid misuse, abuse, and diversionPostgrad Med2011123211913021474900

- ChouRHuffmanLHAmerican Pain Society, American College of PhysiciansMedications for acute and chronic low back pain: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical practice guidelineAnn Intern Med2007147750551417909211

- ChouRFanciulloGJFinePGAmerican Pain Society–American Academy of Pain Medicine Opioids Guidelines PanelClinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer painJ Pain200910211313019187889

- CaldwellJRAvinza – 24-h sustained-release oral morphine therapyExpert Opin Pharmacother20045246947214996642

- RauckRLWhat is the case for prescribing long-acting opioids over short-acting opioids for patients with chronic pain? A critical reviewPain Pract20099646847919874536

- MooreKTSt-FleurDMarriccoNCSteady-state pharmacokinetics of extended-release hydromorphone (OROS hydromorphone): a randomized study in healthy volunteersJ Opioid Manag20106535135821046932

- HaysHHagenNThirlwellMComparative clinical efficacy and safety of immediate release and controlled release hydromorphone for chronic severe cancer painCancer1994746180818167521784

- BrueraESloanPMountBScottJSuarez-AlmazorMA randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, crossover trial comparing the safety and efficacy of oral sustained-release hydromorphone with immediate-release hydromorphone in patients with cancer painJ Clin Oncol1996145171317178622092

- McCarbergBHNicholsonBDToddKHPalmerTPenlesLThe impact of pain on quality of life and the unmet needs of pain management: results from pain sufferers and physicians participating in an Internet surveyAm J Ther200815431232018645331

- MystakidouKClarkAJFischerJLamAPappertKRicharzUTreatment of chronic pain by long-acting opioids and the effects on sleepPain Pract201111328228920854307

- BrennanMJLiebermanJA3rdSleep disturbances in patients with chronic pain: effectively managing opioid analgesia to improve outcomesCurr Med Res Opin20092551045105519292602

- FinePGMahajanGMcPhersonMLLong-acting opioids and short-acting opioids: appropriate use in chronic pain managementPain Med200910Suppl 2S79S8819691687

- PergolizziJVTaylorRJrRaffaRBExtended-release formulations of tramadol in the treatment of chronic painExpert Opin Pharmacother201112111757176821609187

- Parsells KellyJCookSFKaufmanDWAndersonTRosenbergLMitchellAAPrevalence and characteristics of opioid use in the US adult populationPain2008138350751318342447

- Oramorph SR (morphine sulfate) Sustained-Release Tablets, CII [package insert]Newport, KYXanodyne Pharmaceticals, Inc2006

- MS Contin (morphine sulfate controlled-release) Tablets CII [package insert]Stamford, CTPurdue Pharma LP2009

- Kadian (morphine sulfate) Extended-Release Capsules, for oral use, CII [package insert]Morristown, NJActavis Elizabeth LLC2010

- Opana ER (oxymorphone hydrochloride) Extended-Release tablets, for oral use, CII [package insert]Chadds Ford, PAEndo Pharmaceuticals, Inc2008

- Avinza (morphine sulfate extended-release capsules) CII [package insert]Bristol, TNKing Pharmaceuticals, Inc2008

- OxyContin (oxycodone hydrochloride controlled-release) Tablets CII [package insert]Stamford, CTPurdue Pharma LP2010

- Embeda (morphine sulfate and naltrexone hydrochloride) Extended-Release Capsules, for oral use, CII [package insert]Bristol, TNKing Pharmaceuticals2009

- Exalgo (hydromorphone HCl) Extended-Release Tablets (CII) [package insert]Hazelwood, MOMallinckrodt Brand Pharmaceuticals, Inc2012

- Duragesic (fentanyl transdermal system) CII [package insert]Raritan, NJOrtho-McNeil-Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc2009

- Vicodin (hydrocodone bitartrate and acetaminophen tablets, USP) [package insert]North Chicago, ILAbbott Laboratories2011

- PapaleontiouMHendersonCRJrTurnerBJOutcomes associated with opioid use in the treatment of chronic noncancer pain in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysisJ Am Geriatr Soc20105871353136920533971

- FurlanADSandovalJAMailis-GagnonATunksEOpioids for chronic noncancer pain: a meta-analysis of effectiveness and side effectsCMAJ2006174111589159416717269

- KalsoEEdwardsJEMooreRAMcQuayHJOpioids in chronic non-cancer pain: systematic review of efficacy and safetyPain2004112337238015561393

- MurrayAHagenNAHydromorphoneJ Pain Symptom Manage2005295 SupplS57S6615907647

- DroverDRAngstMSValleMInput characteristics and bioavailability after administration of immediate and a new extended-release formulation of hydromorphone in healthy volunteersAnesthesiology200297482783612357147

- TurgeonJGröningRSathyanGThipphawongJRicharzUThe pharmacokinetics of a long-acting OROS hydromorphone formulationExpert Opin Drug Deliv20107113714419961358

- GuptaSSathyanGProviding constant analgesia with OROS® hydromorphoneJ Pain Symptom Manage2007332 SupplS19S24

- BrueraEPereiraJWatanabeSBelzileMKuehnNHansonJOpioid rotation in patients with cancer pain. A retrospective comparison of dose ratios between methadone, hydromorphone, and morphineCancer19967848528578756381

- KnotkovaHFinePGPortenoyRKOpioid rotation: the science and the limitations of the equianalgesic dose tableJ Pain Symptom Manage200938342643919735903

- PalangioMNorthfeltDWPortenoyRKDose conversion and titration with a novel, once-daily, OROS osmotic technology, extended-release hydromorphone formulation in the treatment of chronic malignant or nonmalignant painJ Pain Symptom Manage200223535536812007754

- WallaceMRauckRLMoulinDThipphawongJKhannaSTudorICOnce-daily OROS hydromorphone for the management of chronic nonmalignant pain: a dose-conversion and titration studyInt J Clin Pract200761101671167617877652

- WallaceMRauckRLMoulinDThipphawongJKhannaSTudorICConversion from standard opioid therapy to once-daily oral extended-release hydromorphone in patients with chronic cancer painJ Int Med Res200836234335218380946

- HaleMKhanAKutchMLiSOnce-daily OROS hydromorphone ER compared with placebo in opioid-tolerant patients with chronic low back painCurr Med Res Opin20102661505151820429852

- HannaMThipphawongJ118 Study GroupA randomized, doubleblind comparison of OROS(R) hydromorphone and controlled-release morphine for the control of chronic cancer painBMC Palliat Care200871718976472

- BinsfeldHSzczepanskiLWaechterSRicharzUSabatowskiRA randomized study to demonstrate noninferiority of once-daily OROS® hydromorphone with twice-daily sustained-release oxycodone for moderate to severe chronic noncancer painPain Pract201010540441520384968

- QuigleyCWiffenPA systematic review of hydromorphone in acute and chronic painJ Pain Symptom Manage200325216917812590032

- HannaMTucaAThipphawongJAn open-label, 1-year extension study of the long-term safety and efficacy of once-daily OROS(R) hydromorphone in patients with chronic cancer painBMC Palliat Care200981419754935

- WallaceMSkowronskiRKhannaSTudorICThipphawongJEfficacy and safety evaluation of once-daily OROS hydromorphone in patients with chronic low back pain: a pilot open-label study (DO-127)Curr Med Res Opin200723598198917519065

- WallaceMThipphawongJOpen-label study on the long-term efficacy, safety, and impact on quality of life of OROS hydromorphone ER in patients with chronic low back painPain Med201011101477148821199302

- GalerBSCoyleNPasternakGWPortenoyRKIndividual variability in the response to different opioids: report of five casesPain199249187911375728

- MercadanteSOpioid rotation for cancer pain: rationale and clinical aspectsCancer19998691856186610547561

- Quang-CantagrelNDWallaceMSMagnusonSKOpioid substitution to improve the effectiveness of chronic noncancer pain control: a chart reviewAnesth Analg200090493393710735802

- SlatkinNEOpioid switching and rotation in primary care: implementation and clinical utilityCurr Med Res Opin20092592133215019601703

- FinePGPortenoyRKAd Hoc Expert Panel on Evidence Review and Guidelines for Opioid RotationEstablishing “best practices” for opioid rotation: conclusions of an expert panelJ Pain Symptom Manage200938341842519735902

- WessonDRLingWThe Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS)J Psychoactive Drugs200335225325912924748

- HandelsmanLCochraneKJAronsonMJNessRRubinsteinKJKanofPDTwo new rating scales for opiate withdrawalAm J Drug Alcohol Abuse19871332933083687892

- MahlerDLForrestWHJrRelative analgesic potencies of morphine and hydromorphone in postoperative painAnesthesiology197542560260748347

- FarrarJTYoungJPJrLaMoreauxLWerthJLPooleRMClinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scalePain200194214915811690728

- FarrarJTBerlinJAStromBLClinically important changes in acute pain outcome measures: a validation studyJ Pain Symptom Manage200325540641112727037

- CepedaMSFarrarJTBaumgartenMBostonRCarrDBStromBLSide effects of opioids during short-term administration: effect of age, gender, and raceClin Pharmacol Ther200374210211212891220

- TingNDose Finding in Drug DevelopmentNew York, NYSpringer2006