Abstract

Background

Empirical evidence of the important role of the family in primary pediatric headache has grown significantly in the last few years, although the interconnections between the dysfunctional process and the family interaction are still unclear. Even though the role of parenting in childhood migraine is well known, no studies about the personality of parents of migraine children have been conducted. The aim of the present study was to assess, using an objective measure, the personality profile of mothers of children affected by migraine without aura (MoA).

Materials and methods

A total of 269 mothers of MoA children (153 male, 116 female, aged between 6 and 12 years; mean 8.93 ± 3.57 years) were compared with the findings obtained from a sample of mothers of 587 healthy children (316 male, 271 female, mean age 8.74 ± 3.57 years) randomly selected from schools in the Campania, Umbria, Calabria, and Sicily regions. Each mother filled out the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory – second edition (MMPI-2), widely used to diagnose personality and psychological disorders. The t-test was used to compare age and MMPI-2 clinical basic and content scales between mothers of MoA and typical developing children, and Pearson’s correlation test was used to evaluate the relation between MMPI-2 scores of mothers of MoA children and frequency, intensity, and duration of migraine attacks of their children.

Results

Mothers of MoA children showed significantly higher scores in the paranoia and social introversion clinical basic subscales, and in the anxiety, obsessiveness, depression, health concerns, bizarre mentation, cynicism, type A, low self-esteem, work interference, and negative treatment indicator clinical content subscales (P < 0.001 for all variables). Moreover, Pearson’s correlation analysis showed a significant relationship between MoA frequency of children and anxiety (r = 0.4903, P = 0.024) and low self-esteem (r = 0.5130, P = 0.017), while the MoA duration of children was related with hypochondriasis (r = 0.6155, P = 0.003), hysteria (r = 0.6235, P = 0.003), paranoia (r = 0.5102, P = 0.018), psychasthenia (r = 0.4806, P = 0.027), schizophrenia (r = 0.4350, P = 0.049), anxiety (r = 0.4332, P = 0.050), and health concerns (r = 0.7039, P < 0.001) MMPI-2 scores of their mothers.

Conclusion

This could be considered a preliminary study that indicates the potential value of maternal personality assessment for better comprehension and clinical management of children affected by migraine, though further studies on the other primary headaches are necessary.

Introduction

Migraine without aura (MoA) may be considered the most frequent primary headache in childhood.Citation1 Children affected by migraine have been consistently shown to have more recurrent illnessesCitation2 and school absences, decreased academic performance, social stigma, and impaired ability to establish and maintain peer relationships.Citation3,Citation4 In fact, the quality of life in children with migraine has been shown to be impaired to a degree similar to that in children with arthritis or cancer.Citation5

In order to improve the quality of life of children affected by MoA, alternative drugs and methods have been applied to limit adverse effects,Citation6–Citation9 and many nondrug treatments have been useful in MoA children.Citation10–Citation13

Most studies concerning the impact of migraine have focused on its effects on many aspects of life.Citation14–Citation21 In 1998, Mannix and Solomon reported that people affected by migraine and chronic headaches have a significantly reduced quality of life, even between attacks,Citation22 raising the question of the effects of migraine on quality of life in the broader context of the family. A study on families found that 60% of the participants with migraine believed that their families were significantly affected by their migraines.Citation23 Indeed, it has been argued that the impact of any illness is not only experienced by the individual but also by those around them who are exposed to the various forms of psychological, economic, and social stressors that accompany an illness,Citation24 such as the comparatively high levels of parental stress among the parents of children affected by MoA.Citation25

On the other hand, the empirical evidence of the important role of the family in primary pediatric headache has grown significantly in the last few years, although the interconnections between the dysfunctional process and the family interaction are still unclear.Citation26 However, some authors suggest that migraine could be considered a sort of familial disorder.Citation27 Even though the role of parenting in childhood migraine is well known, no studies about the personality of parents of migraine children have been conducted.

Therefore, the aim of present study was to assess, using an objective measure, the personality profile of mothers of children affected by MoA.

Materials and methods

Study population

A total of 452 children consecutively referred for MoA were enrolled at the Center for Childhood Headache of the Clinic of Child and Adolescent Neuropsychiatry at the Second University of Naples, to the Unit of Child and Adolescent Neuropsychiatry at Perugia University, to the Azienda Sanitaria Locale of Terni, to the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Catanzaro, and to Child Neuropsychiatry at the University of Palermo.

The diagnosis of MoA was made according to the pediatric criteria of the 2013 International Headache Society classification criteria.Citation28 Exclusion criteria were allergies, endocrinological problems (ie, diabetes), preterm birth,Citation29,Citation30 neurological (ie, epilepsy, all types of headache other than MoA) or psychiatric symptoms (attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, depression, behavioral problems), mental retardation (IQ ≤ 70), borderline intellectual functioning (IQ ranging from 71 to 84),Citation31,Citation32 overweight (body mass index [BMI] ≥ 85th percentile) or obesity (BMI ≥ 95th percentile),Citation33,Citation34 sleep disorders,Citation14,Citation35–Citation39 primary nocturnal enuresis,Citation40–Citation42 and anticonvulsantCitation43,Citation44 or psychoactive drug administration.

No children in prophylactic treatment for migraine were recruited for this study. Mothers affected by psychiatric (ie, depression, anxiety, panic attacks, psychosis) or neurological illness or affected by headaches were excluded. Finally, 269 (59.52% from starting population) mothers of MoA children (153 male, 116 female; aged between 6 and 12 years; mean 8.93 ± 3.57 years) were considered eligible for the present study.

Following recruitment, there was a 4-month run-in period to verify headache characteristics. At the end of run-in, monthly headache frequency and mean headache duration were assessed from daily headache diaries kept by all the children. Headache intensity was assessed on a 0–10 visual analog scale (VAS), with 0 being “no pain” and 10 being “the worst possible pain,” as previously reported.Citation10,Citation12,Citation13 The minimum length of headache required for admission in this study was 7 months, with a minimum of four attacks monthly, each lasting for a duration of 1 hour, according to International Classification of Headache Disorders III criteria.Citation28

The results were compared with the findings obtained in a sample of 587 healthy controls (316 male, 271 female; mean age 8.74 ± 3.57 years) randomly selected from schools in the Campania, Umbria, Calabria, and Sicily regions. The subjects in both groups were recruited from the same urban area; participants were all Caucasian, and held a middle-class socioeconomic status (between class 2 or class 3, corresponding to €28,000–€55,000/year to €55,000–€75,000/year, respectively, according to the current Italian economic legislation parameters), as previously reported.Citation17,Citation45

All parents gave their written informed consent. The departmental ethics committee at the Second University of Naples approved the study design. The study was conducted according to the criteria of the Declaration of Helsinki.Citation46

Measures and procedures

Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory – second edition

For assessment of personality habits, each mother filled out the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory – second edition (MMPI-2),Citation47 widely used to diagnose personality and psychological disorders. The MMPI-2 consists of 567 items, all true-or-false format, and usually takes between 1 and 2 hours to be completed. In order to verify the mean differences between the two groups of mothers, we took into account only the two main scales: the clinical basic scale and content scale.

The clinical basic scale is used to evidence different psychotic conditions, and is composed of ten items: hypochondriasis (Hs; to assess a neurotic concern over bodily functioning), depression (D; originally designed to identify depression, characterized by poor morale, lack of hope in the future, and a general dissatisfaction with one’s own life situation), hysteria (Hy; designed to identify the “hysteric” response in stressful situations), psychopathic deviate (Pd; originally developed to identify psychopathic patients, this scale measures social deviation, lack of acceptance of authority, and amorality, and can be considered also as a measure of disobedience), masculinity/femininity (Mf-f; this scale was designed by the original authors to identify homosexual tendencies, but was found to be largely ineffective; high scores on this scale are related to factors such as intelligence, socioeconomic status, and education; women tend to score low on this scale), paranoia (Pa; originally developed to identify patients with paranoid symptoms, such as suspiciousness, feelings of persecution, grandiose self-concepts, excessive sensitivity, and rigid attitudes), psychasthenia (Pt; this scale could be considered more reflective of obsessive–compulsive disorder), schizophrenia (Sc; this scale was originally developed to identify schizophrenic patients and reflects a wide variety of areas, including bizarre thought processes and peculiar perceptions, social alienation, poor familial relationships, difficulties in concentration and impulse control, lack of deep interests, disturbing questions of self-worth and self-identity, and sexual difficulties), hypomania (Ma; this scale was developed to identify such characteristics of hypomania as elevated mood, accelerated speech and motor activity, irritability, flight of ideas, and brief periods of depression), social introversion (Si; this scale is designed to assess the tendency to withdraw from social contacts and responsibilities).

The content scale is composed of 15 items: anxiety (ANX), fears (FRS), obsessiveness (OBS), depression (DEP), health concerns (HEA), bizarre mentation (BIZ), anger (ANG), cynicism (CYN), antisocial practices (ASP), type A (TPA), low self-esteem (LSE), social discomfort (SOD), family problems (FAM), work interference (WRK), and negative treatment indicators (TRT).

In our study, MMPI-2 profiles met all of the following validity criteria: fewer than 30 item omissions, L-scale ≤65, F-scale ≤100, K-scale ≤65, F(b)-scale ≤100, variable response inconsistency T-score ≤80, true response inconsistency T-score ≤80, and raw F-K-score ≤11. The MMPI-2 was evaluated by a trained physician (ME) to assess the personality habits of both mothers of MoA and typical developing children.

Statistical analysis

The t-test was used to compare age and MMPI-2 clinical basic and content scales between mothers of MoA children and typical developing children. Pearson’s correlation test was used to evaluate the relation between MMPI-2 scores of mothers of MoA children and frequency, intensity, and duration of migraine attacks of their children. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The two study groups were not significantly different for age (8.93 ± 3.57 years in MoA group vs 8.74 ± 3.57 in control group, P = 0.519) or sex (ratio male:female 153:116 in MoA group vs 316:271 in control group, P = 0.449).

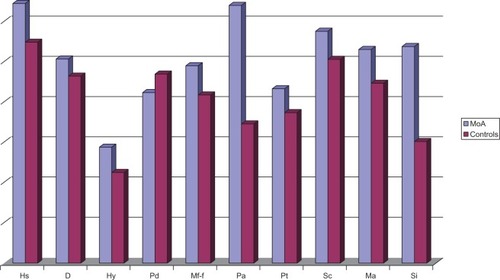

Among the MoA clinical characteristics, in the MoA group the attacks occurred with a mean frequency of 10.21 ± 2.69 a month, a mean duration of 5.92 ± 4.09 hours, and a mean intensity of 6.95 ± 3.41, according to VAS parameters. In the MMPI-2 clinical basic scale, the mothers of MoA children showed significantly higher scores in the Pa and Si (P < 0.001) subscales than mothers of typical developing children ( and ).

Figure 1 Comparisons in MMPI-2 clinical basic scales results between mothers of MoA children and mothers of control children.

Table 1 Differences in clinical basic scale and in content scale of MMPI-2 test among mothers of MoA and typical developing children (controls)

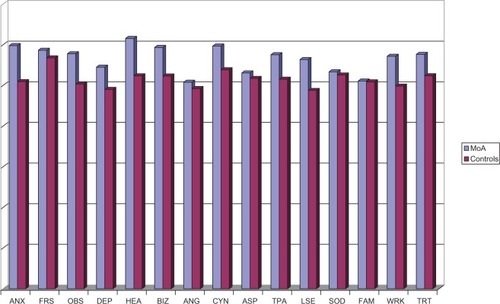

and summarize the differences between the MMPI-2 results in mothers of MoA children in respect of mothers’ comparisons for the content scale. Pearson’s correlation analysis showed a significantly positive relationship between MoA clinical characteristics of studied children and MMPI-2 scores of their mothers. In particular, the MoA frequency of children was significantly positively related with ANX (r = 0.4903, P = 0.024) and LSE (r = 0.5130; P = 0.017) MMPI-2 scores of their mothers.

Figure 2 Comparisons in MMPI-2 content scales results between mothers of MoA children and mothers of control children.

On the other hand, the MoA duration of children was significantly positively related with Hs (r = 0.6155, P = 0.003), Hy (r = 0.6235, P = 0.003), Pa (r = 0.5102, P = 0.018), Pt (r = 0.4806, P = 0.027), Sc (r = 0.4350, P = 0.049), ANX (r = 0.4332, P = 0.050), and HEA (r = 0.7039, P < 0.001) MMPI-2 scores of their mothers.

Discussion

The main findings of the present study suggested that the personality of mothers of children affected by MoA tends to be different compared to controls, with a significant correlation with some migraine characteristics. We preferred to focus exclusively on MoA, because it is the most frequent type of primary headache in childhood and also because MoA takes a significant toll on the quality of life for people affected and their family members.Citation25,Citation48 Consequently, chronic migraine pain may negatively influence daily functioning, emotions, and roles in social and family contexts.Citation48 Moreover, we have to take into account that most studies on the personality traits of migraineurs are focused on adult subjects.Citation49–Citation54 These studies evidenced that psychiatric disorders, including depression and anxiety, can be concomitant with the presence of migraine, adding significant morbidity.Citation55

Overall behavioral disorders have been reported as more common in children who experience headache than in controls.Citation56 Specifically, internalizing symptoms are common in children with headaches, while externalizing symptoms (eg, rule-breaking and aggressivity) are not significantly more common than in controls.Citation57,Citation58

On the other hand, in 2008 Radat et alCitation59 showed a higher prevalence of anxiety and depression in children affected by MoA, while other reports showed low levels of self-concept,Citation60 higher prevalence of harm-avoidance temperamental style,Citation61 and other new and suggestive comorbidities.Citation14–Citation19

Alternatively, psychiatric disorders that run in families, specifically anxiety and mood disorders, are particularly frequent in migraineurs and their relatives,Citation62 and children affected by migraine seem to be characterized by an higher prevalence of psychiatric disorders in parents than comparisons,Citation63 suggesting that a sort of genetic cotransmission of anxiety and depression traits could exist in migraineurs,Citation62 and evidence is pointing in this direction.Citation64 Even though many reports have shown the co-occurrence of psychiatric symptoms in subjects affected by migraine,Citation25,Citation62,Citation63 there have been no specific reports on the personality aspect of mothers not affected by headache who have children with MoA.

Moreover, social learning theory postulates that children’s perception of their physical symptoms can be altered via parental modeling,Citation65 which may affect the expression of pain and functionally somatic symptoms. Children with recurrent unexplained pain report more models and positive reinforcement for pain behavior than children with recurrent explained pain.Citation66 Parental stress and psychopathology may also play a role in organic diseases, such as MoA.Citation25

Family factors, such as parenting styles and family functioning, may be linked with disability levels across children’s physical health problems. However, this body of literature is limited by lack of clarity in distinguishing between individual parenting factors (eg, parenting style), dyadic variables (eg, parent–child communication), and family-level variables (eg, family functioning).Citation67 Clinical studies of children with recurrent headaches and abdominal pain show that their parents report greater levels of family problems,Citation68,Citation69 marital problems,Citation70 divorce and child physical abuse,Citation71 which we could hypothetically also link to the higher levels in mothers of MoA children of some MMPI-2 scores: ANX, OBS, DEP, HEA, BIZ, CYN, TPA, LSE, WRK, and TRT (P < 0.001 for all variables). Specifically, regarding the greater levels of TPA and CYN, we could hypothesize that the personal traits of rigidity and ambition in mothers could impact on the coping-strategy development of children affected by migraine, as the maternal cynism (CYN) could act too. Conversely, a potential link between children’s internalizing disorders, parental psychopathology and headaches has been established.Citation72

Fagan reported that migraine may be associated with dysfunctional parenting patterns, suggesting that in families where the mother has migraine, children may be at risk of inappropriately or prematurely assuming roles for which they are developmentally unready.Citation73 On the other hand, migraine has been also interpreted as a sort of altered communication by children in order to consolidate some intrafamilial trajectories.Citation74,Citation75

Alternatively, our findings seem to suggest a potential role of some maternal personality traits (such as Hs, Hy, Pa, Pt, Sc, ANX, and HEA) in children affected by MoA duration perception (Hs, r = 0.6155, P = 0.003; Hy, r = 0.6235, P = 0.003; Pa, r = 0.5102, P = 0.018; Pt, r = 0.4806, P = 0.027; Sc, r = 0.4350, P = 0.049; ANX, r = 0.4332, P = 0.050; and HEA, r = 0.7039, P < 0.001) and MoA frequency (ANX, r = 0.4903, P = 0.024; and LSE, r = 0.5130, P = 0.017). In fact, we could speculate that some maternal personality traits such as ANX or HEA could alter the health-status perception of children and correct coping strategies, also considering that active coping strategies correspond to intrinsically determined behavior, whereas passive coping corresponds to extrinsically determined behavior with reduced aggression.Citation76

Moreover, passive coping strategies have been reported to be associated with high degrees of headache intensity.Citation77 Several other coping strategies have been described, but in view of the limited number of studies evaluating them, these strategies were considered less determinant for the study of migraine outcomes.Citation59 In this perspective, we could consider our results on the relationship between MMPI-2 basic scales results of mothers, and migraine attacks duration of their children, as the effect of abnormal mothers’ coping styles linked to their peculiar personality profiles.

Obviously, we cannot affirm that maternal personality traits play a causative role in MoA disease, because migraine is undoubtedly a neurological diseaseCitation78,Citation79 and accompanied by many comorbidities at developmental agesCitation14–Citation19 that impact on quality-of-life levels in children affected.

We should take into account a couple of limitations of this study: (1) our data were derived from the administration of a single personality-assessment device and not from a psychiatric clinical evaluation, and (2) we focused only on children affected by MoA, and other types of primary headaches were not considered.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the present study indicates the potential value of maternal personality assessment for better comprehension and clinical management of children affected by migraine, even if further longitudinal studies on the other primary headaches are needed.

In conclusion, our findings could suggest a broader approach to the family of children affected by migraine, with particular attention to the principal caregiver.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- MerikangasKRContributions of epidemiology to our understanding of migraineHeadache20135323024623432441

- PowersSWPattonSRHommelKAHersheyADQuality of life in childhood migraines: clinical impact and comparison to other chronic illnessesPediatrics2003112e1e512837897

- BigalMELiptonRBThe epidemiology, burden, and comorbidities of migraineNeurol Clin20092732133419289218

- VictorTHuXCampbellJBuseDLiptonRMigraine prevalence by age and sex in the United States: a life-span studyCephalalgia2010301065107220713557

- GustavssonASvenssonMJacobiFCost of disorders of the brain in Europe 2010Eur Neuropsychopharmacol20112171877921924589

- Wöber-BingölCPharmacological treatment of acute migraine in adolescents and childrenPaediatr Drugs20131523524623575981

- El-ChammasKKeyesJThompsonNVijayakumarJBecherDJacksonJLPharmacologic treatment of pediatric headaches: a meta-analysisJAMA Pediatr201316725025823358935

- BonfertMStraubeASchroederASReilichPEbingerFHeinenFPrimary headache in children and adolescents: update on pharmacotherapy of migraine and tension-type headacheNeuropediatrics20134431923303551

- GallelliLAvenosoTFalconeDEffects of Acetaminophen and Ibuprofen in Children With Migraine Receiving Preventive Treatment With MagnesiumHeadache2013In press

- CarotenutoMEspositoMNutraceuticals safety and efficacy in migraine without aura in a population of children affected by neurofibromatosis type INeurol Sci2013In press

- VerrottiAAgostinelliSD’EgidioCImpact of a weight loss program on migraine in obese adolescentsEur J Neurol201320239439722642299

- EspositoMRubertoMPascottoACarotenutoMNutraceutical preparations in childhood migraine prophylaxis: effects on headache outcomes including disability and behaviourNeurol Sci20123361365136822437495

- EspositoMCarotenutoMGinkgolide B complex efficacy for brief prophylaxis of migraine in school-aged children: an open-label studyNeurol Sci2011321798120872034

- EspositoMParisiPMianoSCarotenutoMMigraine and periodic limb movement disorders in sleep in children: a preliminary case-control studyJ Headache Pain2013145723815623

- EspositoMRoccellaMParisiLGallaiBCarotenutoMHypersomnia in children affected by migraine without aura: a questionnaire-based case-control studyNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat2013928929423459616

- EspositoMPascottoAGallaiBCan headache impair intellectual abilities in children? An observational studyNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat2012850951323139628

- EspositoMVerrottiAGimiglianoFMotor coordination impairment and migraine in children: a new comorbidity?Eur J Pediatr20121711599160422673929

- CarotenutoMEspositoMPrecenzanoFCastaldoLRoccellaMCosleeping in childhood migraineMinerva Pediatr20116310510921487373

- CarotenutoMEspositoMPascottoAMigraine and enuresis in children: an unusual correlation?Med Hypotheses20107512012220185246

- KantorDThe impact of migraine on school performanceNeurology201279e168e16923109661

- OzgeASaşmazTBuǧdaycıRThe prevalence of chronic and episodic migraine in children and adolescentsEur J Neurol2013209510122882205

- MannixLKSolomonGDQuality of life in migraineClin Neurosci1998538429523057

- SmithRImpact of migraine on the familyHeadache1998384234269664745

- ArmisteadLKlienKForehandRParental physical illness and child functioningClin Psychol Rev199515409422

- EspositoMGallaiBParisiLMaternal stress and childhood migraine: a new perspective on managementNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat2013935135523493447

- OchsMSeemannHFranckGVerresRSchweitzerJFamilial body concepts and illness attributions in primary headache in childhood and adolescencePrax Kinderpsychol Kinderpsychiatr200251209223 German11977402

- SiniatchkinMGerberWDRole of family in development of neurophysiological manifestations in children with migrainePrax Kinderpsychol Kinderpsychiatr20025119420811977401

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS)The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version)Cephalalgia20133362980823771276

- GuzzettaAPizzardiABelmontiVHand movements at 3 months predict later hemiplegia in term infants with neonatal cerebral infarctionDev Med Child Neurol20105276777219863639

- GuzzettaAD’AcuntoMGCarotenutoMThe effects of preterm infant massage on brain electrical activityDev Med Child Neurol201153Suppl 4465121950394

- EspositoMCarotenutoMIntellectual disabilities and power spectra analysis during sleep: a new perspective on borderline intellectual functioningJ Intellect Disabil Res2013In press

- EspositoMCarotenutoMBorderline intellectual functioning and sleep: the role of cyclic alternating patternNeurosci Lett201019485899320813159

- CarotenutoMSantoroNGrandoneAThe insulin gene variable number of tandem repeats (INS VNTR) genotype and sleep disordered breathing in childhood obesityJ Endocrinol Invest20093275275519574727

- CarotenutoMBruniOSantoroNDel GiudiceEMPerroneLPascottoAWaist circumference predicts the occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing in obese children and adolescents: a questionnaire-based studySleep Med2006735736116713341

- CarotenutoMGuidettiVRujuFGalliFTaglienteFRPascottoAHeadache disorders as risk factors for sleep disturbances in school aged childrenJ Headache Pain2005626827016362683

- CarotenutoMGallaiBParisiLRoccellaMEspositoMAcupressure therapy for insomnia in adolescents: a polysomnographic studyNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat2013915716223378768

- CarotenutoMGimiglianoFFiordelisiGRubertoMEspositoMPositional abnormalities during sleep in children affected by obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: the putative role of kinetic muscular chainsMed Hypotheses20138130630823660129

- CarotenutoMEspositoMParisiLDepressive symptoms and childhood sleep apnea syndromeNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat2012836937322977304

- CarotenutoMEspositoMPascottoAFacial patterns and primary nocturnal enuresis in childrenSleep Breath20111522122720607423

- EspositoMCarotenutoMRoccellaMPrimary nocturnal enuresis and learning disabilityMinerva Pediatr2011639910421487372

- EspositoMGallaiBParisiLPrimary nocturnal enuresis as a risk factor for sleep disorders: an observational questionnaire-based multicenter studyNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat2013943744323579788

- EspositoMGallaiBParisiLVisuomotor competencies and primary monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis in prepubertal aged childrenNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat2013992192623847418

- CoppolaGAuricchioGFedericoRCarotenutoMPascottoALamotrigine versus valproic acid as first-line monotherapy in newly diagnosed typical absence seizures: an open-label, randomized, parallel-group studyEpilepsia2004451049105315329068

- CoppolaGLicciardiFSciscioNRussoFCarotenutoMPascottoALamotrigine as first-line drug in childhood absence epilepsy: a clinical and neurophysiological studyBrain Dev200426262914729411

- EspositoMAntinolfLGallaiBExecutive dysfunction in children affected by obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: an observational studyNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat20131091087109423976855

- World Medical AssociationWMA Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human SubjectsFerney-Voltaire, FranceWMA2008 Available from: http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3Accessed April 25, 2013

- ButcherJNDahlstromWGGrahamJRTellegenAKaemmerBMinnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2): Manual for Administration and ScoringMinneapolisUniversity of Minnesota Press1989

- LiptonRBBigalMEAmatniekJCStewartWFTools for diagnosing migraine and measuring its severityHeadache20044438739815147245

- IshiiMShimizuSSakairiYMAOA, MTHFR, and TNF-β genes polymorphisms and personality traits in the pathogenesis of migraineMol Cell Biochem201236335736622193458

- HedborgKAnderbergUMMuhrCStress in migraine: personality-dependent vulnerability, life events, and gender are of significanceUps J Med Sci201111618719921668386

- CuroneMTulloVMeaEProietti-CecchiniAPeccarisiCBussoneGPsychopathological profile of patients with chronic migraine and medication overuse: study and findings in 50 casesNeurol Sci201132Suppl 1S177S17921533740

- LuconiRBartoliniMTaffiRPrognostic significance of personality profiles in patients with chronic migraineHeadache2007471118112417883516

- TanHJSuganthiCDhachayaniSRizalAMRaymondAAThe coexistence of anxiety and depressive personality traits in migraineSingapore Med J20074830731017384877

- Abbate-DagaGFassinoSLo GiudiceRAnger, depression and personality dimensions in patients with migraine without auraPsychother Psychosom20077612212817230053

- BreslauNSchultzLRStewartWFLiptonRBLuciaVCWelchKMHeadache and major depression: is the association specific to migraine?Neurology20005430831310668688

- PavonePRizzoRContiIPrimary headaches in children: clinical findings on the association with other conditionsInt J Immunopathol Pharmacol2012251083109123298498

- ArrudaMABigalMEBehavioral and emotional symptoms and primary headaches in children: a population-based studyCephalalgia2012321093110022988005

- MargariFLucarelliECraigFPetruzzelliMGLeccePAMargariLPsychopathology in children and adolescents with primary headaches: categorical and dimensional approachesCephalalgia EpubJuly42013

- RadatFMekiesCGéraudGAnxiety, stress and coping behaviours in primary care migraine patients: results of the SMILE studyCephalalgia2008281115112518644041

- EspositoMGallaiBParisiLSelf-concept evaluation and migraine without aura in childhoodNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat201391061106623950647

- EspositoMMarottaRGallaiBTemperamental characteristics in childhood migraine without aura: a multicenter studyNeuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment201391187119223983467

- MerikangasKRMerikangasJRAngstJHeadache syndromes and psychiatric disorders: association and familial transmissionJ Psychiatr Res1993271972108366469

- GalliFCanzanoLScalisiTGGuidettiVPsychiatric disorders and headache familial recurrence: a study on 200 children and their parentsJ Headache Pain20091018719719352592

- GondaXRihmerZJuhaszGZsombokTBagdyGHigh anxiety and migraine are associated with the s allele of the 5HTTLPR gene polymorphismPsychiatr Res2007149261266

- BanduraASelf-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral changePsychol Rev197784191215847061

- OsborneRBHatcherJWRichtsmeierAJThe role of social modeling in unexplained pediatric painJ Pediatr Psychol19891443612723955

- PalermoTMChambersCTParent and family factors in pediatric chronic pain and disability: an integrative approachPain20051191416298492

- AnttilaPSouranderAMetsähonkalaLAromaaMHeleniusHSillanpääMPsychiatric symptoms in children with primary headacheJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry20044341241915187801

- EmirogluFNKurulSAkayAMiralSDirikEAssessment of child neurology outpatients with headache, dizziness and faintingJ Child Neurol20041933233615224706

- ZuckermanBStevensonJBaileyVStomachaches and headaches in a community sample of preschool childrenPediatrics1987796776823575021

- JuangKDWangSJFuhJLLuSRChenYSAssociation between adolescent chronic daily headache and childhood adversity: a community-based studyCephalalgia200424545914687014

- FeldmanJMOrtegaANKoinis-MitchellDKuoAACaninoGChild and family psychiatric and psychological factors associated with child physical health problems: results from the Boricua youth studyJ Nerv Ment Dis201019827227920386256

- FaganMAExploring the relationship between maternal migraine and child functioningHeadache2003431042104814629239

- GuidettiVGalliFFabriziPHeadache and psychiatric comorbidity: clinical aspects and outcome in an 8-year follow-up studyCephalalgia1998184554629793697

- GuidettiVPagliariniMCortesiFMother and children with primary headache. A psychometric and psychological studyMinerva Med19877810231026 Italian3601144

- BenusRFBohusBKoolhaasJMvan OortmerssenGAHeritable variation for aggression as a reflection of individual coping strategiesExperientia199147100810191936199

- MarloweNStressful events, appraisal, coping and recurrent headacheJ Clin Psychol1998542472569467769

- CortelliPPierangeliGMontagnaPIs migraine a disease?Neurol Sci201031Suppl 1S29S3120464579

- BalottinUChiappediMRossiMTermineCNappiGChildhood and adolescent migraine: a neuropsychiatric disorder?Med Hypotheses20117677878121356578