Abstract

Background

The association between depression, anxiety, and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is still unclear. Therefore, a systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted to assess the rates of comorbid psychiatric disorders among women with PCOS compared to women without it.

Methods

PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, and Web of Science databases were searched from inception to November 27, 2015. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they were original reports in which the rates of mood (bipolar disorder, dysthymia, or major depressive disorder), obsessive–compulsive spectrum disorders, trauma- and stressor-related disorders, anxiety disorders or psychotic disorders, somatic symptom and related disorders, or eating disorders had been investigated among women with an established diagnosis of PCOS and compared with women without PCOS. Psychiatric diagnosis should have been established by means of a structured diagnostic interview or through a validated screening tool. Data were extracted and pooled using random effects models.

Results

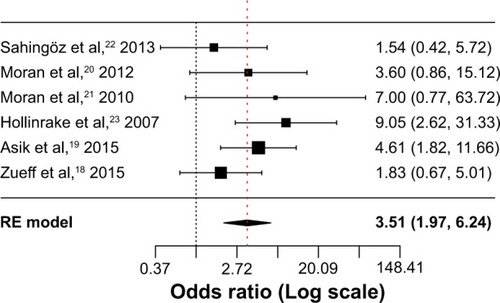

Six studies were included in the meta-analysis; of these, five reported the rates of anxiety and six provided data on the rates of depression. The rate of subjects with anxiety symptoms was higher in patients with PCOS compared to women without PCOS (odds ratio (OR) =2.76; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.26 to 6.02; Log OR =1.013; P=0.011). The rate of subjects with depressive symptoms was higher in patients with PCOS compared to women without PCOS (OR =3.51; 95% CI 1.97 to 6.24; Log OR =1.255; P<0.001).

Conclusion

Anxiety and depression symptoms are more prevalent in patients with PCOS.

Introduction

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a complex genetic disease that affects approximately 7% of women of reproductive age worldwide.Citation1 PCOS is a heterogeneous disorder, where the main clinical features include menstrual irregularities, subfertility, hyperandrogenism, and hirsutism.Citation2

Numerous studies have evaluated the relation between PCOS and psychiatric disorders; however, most have evaluated psychiatric symptoms based on self-report measures.Citation1,Citation3 There remains, therefore, an unclear relationship between PCOS and psychiatric disorders. Cross-sectional epidemiological studies have reported that individuals with PCOS are more likely to have anxiety or depressive disorders when compared to those in the general population.Citation4 Two studies have shown depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, and binge eating disorder are more frequent among women with PCOS compared with controls.Citation5,Citation6

PCOS is accompanied by an array of symptoms such as obesity, acne, scalp hair thinning, menstrual irregularity, and subfertility. These symptoms can also contribute to psychological impairment.Citation7 Despite the use of antidepressants in the treatment of depressive symptoms, there has been only one report to date on the use of serotonin reuptake inhibitors with a successful outcome in a patient with PCOS.Citation8

In light of the above mentioned, the purpose of the present study is to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of the rates of mood (bipolar disorder, dysthymia, or major depressive disorder), obsessive–compulsive spectrum disorders, trauma- and stressor-related disorders, anxiety disorders, psychotic disorders, somatic symptom and related disorders, binge eating disorders and eating disorders among women with an established diagnosis of PCOS compared to those without PCOS.

Materials and methods

A systematic review and meta-analysis was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) and the Cochrane group guideline recommendations.Citation9,Citation10 The process includes literature review, eligibility criteria of the retrieved references, assessment of the methodological quality of included studies, extraction of outcomes and relevant variables, and meta-analysis of the data.

Search strategy

We searched the PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, and Web of Science databases from inception to November 27, 2015. This search strategy was augmented by hand-searching through reference lists of included articles and by tracking the citations of eligible references in Google Scholar.

Eligibility criteria

We included original reports in which the rates of mood (bipolar disorder, dysthymia, or major depressive disorder), obsessive–compulsive spectrum disorders, trauma- and stressor-related disorders, anxiety disorders, psychotic disorders, somatic symptom and related disorders, and eating disorders have been investigated among women with an established diagnosis of PCOS and compared to women without PCOS. Psychiatric diagnosis should have been established by means of a structured diagnostic interview according to either Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) or International Classification of Diseases (ICD) criteria. Studies in which a diagnosis of psychiatric disorder had been established through a validated screening tool above a preestablished cutoff were also considered for inclusion. A diagnosis of PCOS could be established by means of the Rotterdam, National Institutes of Health (NIH), or PCOS Society criteria.Citation11 We included original peer-reviewed studies published in English, Portuguese, French, Spanish, or German. Either population-based or studies performed in clinical samples were eligible for inclusion. Meeting abstracts were excluded. We also excluded studies performed in pediatric populations.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the odds ratios (ORs) of psychiatric disorders among women with PCOS compared to women without PCOS.

Search strategy (November 27, 2015)

PubMed/MEDLINE

Search 1: ((((((((“Depression”[Mesh] OR “Depressive Disorder”[Mesh] OR “Depression, Postpartum”[Mesh] OR “Depressive Disorder, Major”[Mesh] OR “Bipolar Disorder”[Mesh]) OR “Anxiety Disorders”[Mesh]) OR “Phobic Disorders”[Mesh]) OR “Stress Disorders, Post-Traumatic”[Mesh]) OR “Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder”[Mesh]) OR “Psychotic Disorders”[Mesh]) OR (“Schizophrenia”[Mesh] OR “Schizophrenia and Disorders with Psychotic Features”[Mesh])) OR “Somatoform Disorders”[Mesh]) OR (“Eating Disorders”[Mesh] OR “Binge Eating Disorder”[Mesh]) Field: Title/Abstract.

Search 2: “Polycystic Ovary Syndrome”[Mesh] Field: Title/Abstract.

Search 3: #1 AND #2.

Retrieved references: 171.

OVID databases (PsycINFO and Embase Classic plus Embase)

Search 1: “polycystic ovary syndrome”.ti,ab,kw

Search 2: (“depression” or “depressive disorder” or “major depressive disorder” or “bipolar disorder” or “mania” or “postpartum depression” or “somatoform disorder” or “binge eating disorder” or “eating disorder” or “anxiety disorder” or “post-traumatic stress disorder” or “obsessive compulsive disorder” or “psychosis” or “psychotic disorder” or “schizophrenia” or “bulimia” or “anorexia nervosa”).

Search 3: #1 and #2.

Retrieved References: 360.

Selection of eligible studies

This systematic review complied with PRISMA guidelines;

the primary (ie, title/abstract) screening was independently performed by two researchers (SLB and JVAA), supervised by ICP, who made the final decision in cases of disagreement;

the PDFs (ie, full-texts) of potentially eligible articles were retrieved;

the secondary screening was independently performed by two researchers (SLB and JVAA), supervised by ICP, who made the final decision in cases of disagreement;

disagreements were resolved through consensus.

Quality assessment

We used the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOQAS) to assess the quality of included studies.Citation12 Overall quality score was defined as the percentage of criteria that were met by each included study. We excluded NOQAS items 4 and 7 because these were meaningless for the context of the current study. The agreement of independent raters (SLB and JVAA) was excellent (Cohen’s kappa =0.91; standard error (SE) =0.05).

Data extraction

We built Excel spreadsheets to extract data from included articles. We used the version X7 of EndNote to remove duplicate data. The characteristics extracted from each study were: name of the first author; publication year; country; number, sex, and age of the patients and controls; type of diagnostic criteria used to assess PCOS (Rotterdam, NIH, or PCOS Society) and the psychiatric disorders (DSM or ICD); whether patients were medication free; latitude of the city where the study was performed; mean age of the total sample size; type of study (population-based or clinical study); whether the diagnoses of psychiatric disorders were assessed through structured interviews; NOQAS items.

Data analysis

We used the metaphor package for R (version number 3.2.3) to do the meta-analysis with binary data and meta-regression analysis.Citation13 We undertook meta-analyses whenever values of the rate of a specific psychiatric disorder in patients with PCOS compared to healthy controls were available in two or more studies.Citation13 A random-effects model with restricted maximum-likelihood estimator was used to synthesize the effect size across studies. This model can incorporate both within-study variability and between-study variability.Citation13 The OR and Log OR were used to assess the effect size.Citation8 The significance level for this meta-analysis model was 0.05.Citation13 Egger’s linear regression test was used to assess publication bias. This is a test for asymmetry of the funnel plot, and it was done whenever three or more studies were included.Citation14 For this specific test a P-value of less than 0.1 shows significant asymmetry and therefore publication bias.Citation14 If Egger’s linear regression test revealed a potential publication bias, we used Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill method to test the data. We also used the so-called leave-one-out function for doing sensitivity analysis.Citation13 This method consists of the removal of one study at a time from the dataset to run the meta-analysis without it. This analysis tests if the effect size of the meta-analysis is driven by one study. We used the Q statistic to test the existence of heterogeneity and I2 to assess the proportion of total variability due to heterogeneity.Citation15 An I2 value of ~25% could be regarded as low, ~50% as medium, and ~75% as high.Citation9 We used τ2 to estimate the total amount of heterogeneity.Citation15

We explored sources of heterogeneity in studies using univariate meta-regression analysis.Citation16,Citation17 We selected the latitude of the city where the study was performed, type of diagnostic criteria used to define PCOS, mean age of the total sample size of the included studies, type of study, total sample size of the PCOS group of the included studies, whether the diagnoses of psychiatric disorders were assessed through structured interviews, and quality of the included studies as assessed by the NOQAS as moderator. A pseudo-R2 statistic is given for each analysis, showing the percentage of total heterogeneity in the true effects that is accounted for by the model with all covariates included.

Results

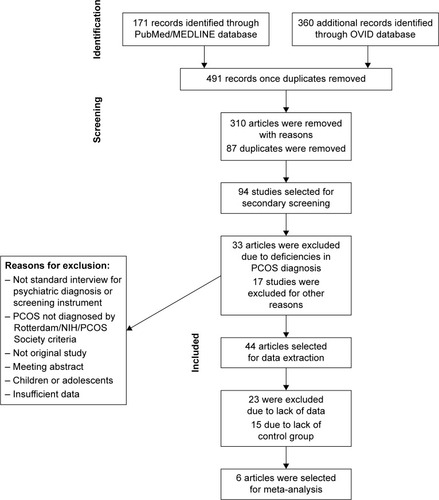

shows the study selection process. Quality and characteristics of included studies are described in .

Figure 1 PRISMA flowchart of systematic review.

Table 1 Quality and characteristics of included studies

Anxiety symptoms

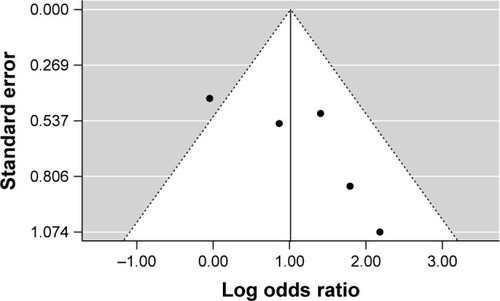

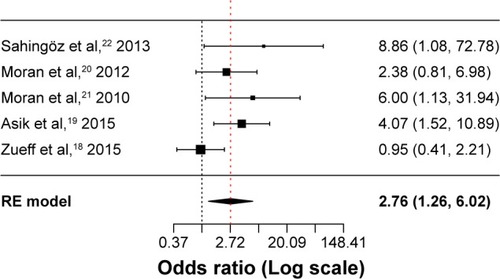

A total of five studies were included in this meta-analysis.Citation18–Citation22 The rate of subjects with anxiety symptoms was higher in patients with PCOS compared to healthy controls (OR =2.76; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.26 to 6.02; Log OR =1.013; P=0.011). shows the forest plot and the OR of the pooled analysis (Log scale was used in the x axis) while shows the funnel plot (Log OR was used for the funnel plot). Egger’s linear regression test revealed potential publication bias (z=1.869, P=0.061). We, therefore, performed Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill method, and the result for the rate of anxiety symptoms in patients with PCOS was still higher compared to healthy controls (OR =2.40; 95% CI 1.16 to 4.97; Log OR =0.874; P=0.018 – one study was estimated on the left side). The significance of the effect size remained robust when leave-one-out models were used for such meta-analysis (see – results were presented with Log OR). No significant heterogeneity was found (Q statistic =8.345, df=4, P=0.079; I2=51.73%; τ2=0.389). In our investigation of covariates using univariate meta-regression analyses, we found that latitude of the city where the study was performed (estimate =0.010; 95% CI −0.013 to 0.034; P=0.375), type of diagnostic criteria used to define PCOS (estimate =0.393; 95% CI −1.452 to 2.240; P=0.675), mean age of the total sample size of the included studies (estimate =−0.123; 95% CI −0.264 to 0.017; P=0.085), type of study (estimate =0.393; 95% CI −1.452 to 2.240; P=0.675), total sample size of the PCOS group of the included studies (estimate =0.012; 95% CI −0.032 to 0.056; P=0.597) and whether the diagnoses of psychiatric disorders were assessed through structured interviews (estimate =−1.307; 95% CI −3.848 to 1.233; P=0.313) did not moderate the effect size. It is worth mentioning that quality of the included studies as assessed by the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale also did not moderate the effect size (estimate =−0.711; 95% CI −1.317 to −0.104; P=0.021).

Figure 2 Forest plot of the studies assessing anxiety symptoms.

Table 2 Leave-one-out models for the meta-analysis of anxiety symptoms

Depressive symptoms

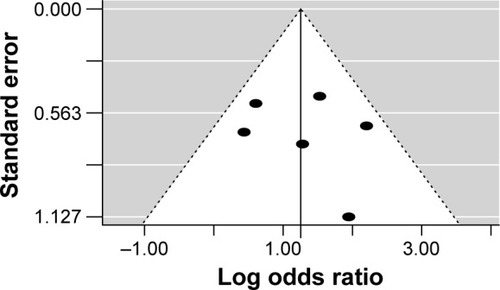

A total of six studies were included in this meta- analysis.Citation18–Citation20,Citation22,Citation23 The rate of subjects with depressive symptoms was higher in patients with PCOS compared to healthy controls (OR =3.51; 95% CI 1.97 to 6.24; Log OR =1.255; P<0.001). shows the forest plot and the OR of the pooled analysis (Log scale was used in the x axis) while shows the funnel plot (Log OR was used for the funnel plot). Egger’s linear regression test revealed no potential publication bias (z=0.499, P=0.618). The significance of the effect size remained robust when leave-one-out models were used for such meta-analysis (see – results were presented with Log OR). We found no significant between-study heterogeneity (Q statistic =6.055, df=5, P=0.301; I2=22.17%; τ2=0.338). In our investigation of covariates using univariate meta-regression analyses, we found the city’s latitude where the study was performed (estimate =0.005; 95% CI −0.012 to 0.022; P=0.551), type of diagnostic criteria used to define PCOS (estimate =−0.606; 95% CI −1.926 to 0.713; P=0.367), mean age of the total sample size of the included studies (estimate =−0.069; 95% CI −0.201 to 0.061; P=0.298), type of study (estimate =−0.606; 95% CI −1.926 to 0.713; P=0.367), total sample size of the PCOS group of the included studies (estimate =0.011; 95% CI −0.009 to 0.032; P=0.284), and whether the diagnoses of psychiatric disorders were assessed through structured interviews (estimate =−0.531; 95% CI −3.485 to 2.422; P=0.724) did not moderate the effect size. It is worth mentioning that quality of the included studies as assessed by the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale also did not moderate the effect size (estimate =−0.131; 95% CI −0.929 to 0.667; P=0.747). We did not analyze structured psychiatric diagnosis as a moderator since no study used it.

Figure 4 Forest plot of the studies that assessed depressive symptoms.

Table 3 Leave-one-out models for the meta-analysis of depressive symptoms

Discussion

This systematic review found six studies that study the association of PCOS with depression or anxiety in young women (22.4 to 32 years old in the PCOS group and 24.9 to 36.4 years old in the control group) in clinical settings, performed in four countries (Turkey, Australia, Brazil, United States). Methodologically, all studies selected were performed in clinical settings, with a good overall assessment of quality, although they showed some different characteristics, such as sample size (between 46 and 206 individuals), differences in the criteria used to diagnose PCOS as well as a difference in the instruments used to assess anxiety and/or depression. Particularly, the lack of a unified concept of PCOS and differences in the assessment of psychiatric diagnosis across studies hindered comparisons. However, we were not able to identify potential sources of heterogeneity (latitude, type of diagnostic criteria used to define PCOS, mean age, type of study, total sample size of the PCOS group, assessment of psychiatric disorders, and methodological quality of the study). These results should be considered exploratory in nature as few studies may undermine the statistical power of meta-regression techniques.

Overall, in the present meta-analysis, we found that rates of anxiety and depressive symptoms were higher in patients with PCOS compared to healthy controls in line with distinct clinical studies suggesting the increased prevalence of anxiety and depression in women with PCOS.

Clinical and research implications

Results from this systematic review indicate that specialized literature shows that a limited number of studies have assessed the prevalence of psychiatric conditions in women with PCOS compared to healthy controls. Only six studies were selected. The main finding was that women with PCOS have a higher prevalence rate of anxiety and depression.

Potential mechanisms for these associations may include social, psychological, and neurobiological aspects. Women with PCOS may report clinically significant symptoms of anxiety or depression at least in part as a result of significant body changes imposed by their illness (eg, hirsutism, irregular menses, obesity, acne, hair thinning).Citation2,Citation7 Previous research indicates that alterations in body image may contribute to psychological distress among women with PCOS.Citation24

The literature on neurobiological research in anxiety disorders, anxiety symptoms, depressive disorders, and depressive symptoms among women with PCOS encompasses hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis activity and neuroimaging studies.Citation25

The neurophysiologic etiology of anxiety and depression is not fully understood but the dysregulation of the HPA axis has been linked to stress and, although less extensively, its putative association with anxiety and depression disorders has also been studied.Citation26

Higher basal cortisol levels have been described in depression, panic disorder, and generalized anxiety disorders. In the latter condition, studies suggest that such dysregulation may be state dependent, as higher cortisol levels can be found in persons with current anxiety disorder and borderline cortisol levels for those with remitted symptoms.Citation27 The maintenance of basal HPA tone is essential for homeostasis, which is usually disrupted in depressive and PCOS patients.Citation25,Citation26,Citation28–Citation30 There is evidence showing women with PCOS have several HPA changes such as abnormal androgen synthesis and secretion, enhanced peripheral metabolism of cortisol,Citation31 compensatory overdrive of HPA,Citation10 and impaired feedback inhibition is likely in patients with major depression.Citation11,Citation12 These changes might explain some of the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms of the association between PCOS and depression.

Through imaging studies there is a body of evidence suggesting that lateral and medial regions of the prefrontal cortex (PFC) modulate amygdala and related limbic structures during effortful emotion regulation. Anxiety disorders may be linked to an imbalance between the PFC and the amygdala. Marsh et al assessed mood, metabolic function, and neuronal activation during an emotional task through functional magnetic resonance imaging, and µ-opioid receptor availability using positron emission tomography within PCOS patients. Major findings indicated patients with PCOS had significantly greater activity in the PFC and ventral anterior cingulate cortex compared to controls.Citation25

Clinical and research impact

Women with more serious PCOS symptoms are probably more likely to get treatment from their gynecologists. It should be emphasized that consultation is an opportunity to assess not only the clinical aspects of PCOS but also the clinical symptoms of anxiety or depression that could be effectively treated. In addition, it is a chance to address concerns that are not necessarily associated with a psychiatric condition or a psychiatric diagnosis (eg, marital, family, social issues, low level of quality of life, sexual dysfunction, low self-esteem) that often could be PCOS associated.

Given the seriousness of anxiety and depression conditions in women with PCOS, further study of epidemiology, clinical features, neurobiology, disability, quality of life, and treatment in different settings and countries is needed to better understand this association.

Two other reviews analyzing the relation between depression and anxiety and PCOS were found. Both, Barry et al and Veltman-Verhulst et al arrived at similar conclusions found in this study, even though the number of articles investigated in those studies differed mainly due to different inclusion and exclusion criteria.Citation32,Citation33

Conclusion

Results from this systematic review indicate that specialized literature shows a lack of data on the association of PCOS and mental disorders. Only six studies were selected and even these used heterogeneous concepts of assessment.

Individuals with PCOS showed a greater prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms. New investigations could focus on establishing standard assessment procedures as well as undertaking a cost–benefit assessment to establish whether treating anxiety and depression in individuals with PCOS could lead to better directives on the treatment of these patients.

Limitations

This systematic review is characterized by the following limitations: (1) the search for studies eligible for inclusion was performed using electronic databases and only studies published in specialized literature, rather than in books, textbooks, or theses, were selected; (2) according to the criteria for inclusion in this review, the selection of languages could have excluded studies performed in other countries or continents; (3) a reduced number of studies was included, which restricted the performance of a meta-analysis; (4) the instruments to assess anxiety or depression were different across studies; (5) the NOQAS for assessing the methodological quality of each study was adapted for the purposes of our analysis; however, inter-rater reliability of the scale was kept appropriate; (6) the use of obese patientsCitation16 as a control group in one study could affect the results of this review. However, sensitivity analysis did not show that such a control group affected the study conclusions.

Suggestions for future research

New studies on the prevalence of anxiety and depression in individuals with PCOS are needed. Uniformity of concepts of PCOS, anxiety and depression in research and collaboration among different centers are strategies that could promote knowledge about this issue. In addition, studies specifically aimed at the investigation of the association between PCOS and anxiety and/or depression in adolescents, adults, and other minority groups could be relevant, as well as the analysis of other potential confounders (hormone therapy, medical treatment for PCOS, multiple drug interaction, etc). In view of the considerable potential of anxiety and depression disorders to impair functional ability,Citation34 studies investigating whether treating these conditions could improve the outcome of these patients should be greatly encouraged.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq; Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico) to SLB, research grant (Bolsista de Produtividade em Pesquisa 305274/2014-7).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- DunaifAPolycystic ovary syndrome in 2011: genes, aging and sleep apnea in polycystic ovary syndromeNat Rev Endocrinol2012827274

- AliATPolycystic ovary syndrome and metabolic syndromeCeska Gynekol201580427928926265416

- AnnagurBBKerimogluOSTazegulAGunduzSGencogluBBPsychiatric comorbidity in women with polycystic ovary syndromeJ Obstet Gynaecol Res20154181229123325833092

- DokrasAMood and anxiety disorders in women with PCOSSteroids201277433834122178257

- Davari-TanhaFHosseini RashidiBGhajarzadehMNoorbalaAABipolar disorder in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCO)Acta Med Iran2014521464824658986

- KerchnerALesterWStuartSPDokrasARisk of depression and other mental health disorders in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a longitudinal studyFertil Steril200991120721218249398

- NaqviSHMooreABevilacquaKPredictors of depression in women with polycystic ovary syndromeArch Womens Ment Health20151819510125209354

- BlaySLA case of major depressive disorder and symptoms of polycystic ovary syndrome responding to escitalopramPrim Care Companion CNS Disord2011136

- MoherDLiberatiATetzlaffJAltmanDGPRISMA GroupPreferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statementJ Clin Epidemiol200962101006101219631508

- HigginsJPTGreenSCochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.2The Cochrane Collaboration2008

- Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS consensus workshop groupRevised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)Hum Reprod2004191414714688154

- WellsGASheaBO’ConnellDThe Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analysesOttawa, ONOttawa Hospital Research Institute2011 Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.aspAccessed September 21, 2016

- ViechtbauerWConducting Meta-Analyses in R with the metafor PackageJournal of Statistical Software2010363148

- EggerMDavey SmithGSchneiderMMinderCBias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical testBMJ199731571096296349310563

- HigginsJPThompsonSGQuantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysisStat Med200221111539155812111919

- Van HouwelingenHCArendsLRStijnenTAdvanced methods in meta-analysis: multivariate approach and meta-regressionStat Med200221458962411836738

- ThompsonSGSharpSJExplaining heterogeneity in meta-analysis: a comparison of methodsStat Med199918202693270810521860

- ZueffLNda Silva LaraLAVieiraCSMartins WdePFerrianiRABody composition characteristics predict sexual functioning in obese women with or without PCOSJ Sex Marital Ther201541322723724274091

- AsikMAltinbasKErogluMEvaluation of affective temperament and anxiety-depression levels of patients with polycystic ovary syndromeJ Affect Dis201518521421826241866

- MoranLJDeeksAAGibson-HelmMETeedeHJPsychological parameters in the reproductive phenotypes of polycystic ovary syndromeHum Reprod20122772082208822493025

- MoranLGibson-HelmMTeedeHDeeksAPolycystic ovary syndrome: a biopsychosocial understanding in young women to improve knowledge and treatment optionsJ Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol2010311243120050767

- SahingözMUguzFGezgincKKorucuDGAxis I and Axis II diagnoses in women with PCOSGen Hosp Psychiatry201335550851123726743

- HollinrakeEAbreuAMaifeldMVan VoorhisBJDokrasAIncreased risk of depressive disorders in women with polycystic ovary syndromeFertil Steril20078761369137617397839

- HimeleinMJThatcherSSDepression and body image among women with polycystic ovary syndromeJ Health Psychol200611461362516769740

- MarshCABerent-SpillsonALoveTFunctional neuroimaging of emotional processing in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a case-control pilot studyFertil Steril20131001200207.e123557757

- MuellerSCNgPSinaiiNPsychiatric characterization of children with genetic causes of hyperandrogenismEur J Endocrinol2010163580181020807778

- VreeburgSAZitmanFGvan PeltJSalivary cortisol levels in persons with and without different anxiety disordersPsychosom Med201072434034720190128

- LanzoneAPetragliaFFulghesuAMCiampelliMCarusoAMancusoSCorticotropin-releasing hormone induces an exaggerated response of adrenocorticotropic hormone and cortisol in polycystic ovary syndromeFertil Steril1995636119511997750588

- MahmoudRWainwrightSRGaleaLASex hormones and adult hippocampal neurogenesis: regulation, implications, and potential mechanismsFront Neuroendocrinol20164112915226988999

- ParianteCMLightmanSLThe HPA axis in major depression: classical theories and new developmentsTrends Neurosci200831946446818675469

- MacutDBozic AnticINestorovJThe influence of combined oral contraceptives containing drospirenone on hypothalamic-pituitary- adrenocortical axis activity and glucocorticoid receptor expression and function in women with polycystic ovary syndromeHormones (Athens)201514110911725402380

- BarryJAKuczmierczykARHardimanPJAnxiety and depression in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysisHum Reprod20112692442245121725075

- Veltman-VerhulstSMBoivinJEijkemansMJFauserBJEmotional distress is a common risk in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 28 studiesHum Reprod Update201218663865122824735

- WhitefordHADegenhardtLRehmJGlobal burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010Lancet201338299041575158623993280