Abstract

Although the physiological and psychological mechanisms involved in the development of sleep disorders remain similar throughout history, factors that potentiate these mechanisms are closely related to the “zeitgeist”, ie, the sociocultural, technological and lifestyle trends which characterize an era. Technological advancements have afforded modern society with 24-hour work operations, transmeridian travel and exposure to a myriad of electronic devices such as televisions, computers and cellular phones. Growing evidence suggests that these advancements take their toll on human functioning and health via their damaging effects on sleep quality, quantity and timing. Additional behavioral lifestyle factors associated with poor sleep include weight gain, insufficient physical exercise and consumption of substances such as caffeine, alcohol and nicotine. Some of these factors have been implicated as self-help aids used to combat daytime sleepiness and impaired daytime functioning. This review aims to highlight current lifestyle trends that have been shown in scientific investigations to be associated with sleep patterns, sleep duration and sleep quality. Current understanding of the underlying mechanisms of these associations will be presented, as well as some of the reported consequences. Available therapies used to treat some lifestyle related sleep disorders will be discussed. Perspectives will be provided for further investigation of lifestyle factors that are associated with poor sleep, including developing theoretical frameworks, identifying underlying mechanisms, and establishing appropriate therapies and public health interventions aimed to improve sleep behaviors in order to enhance functioning and health in modern society.

Keywords:

Introduction

The discipline of modern sleep medicine is dated back to the early 1950s, following the discovery of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and the identification of nightly sleep stage distribution.Citation1,Citation2 While much basic and clinical research has been done in the past six decades, advancing our understanding of the etiology and mechanisms underlying sleep disorders on the one hand, and enabling the application of clinical diagnosis and treatment practices on the other, it is important to keep in mind that sleep disorders existed and were described long before the mid-20th century.

Ancoli-IsraelCitation3 has investigated references to sleep in the Bible and the Talmud, regarding the function of sleep, the consequences of both sleep deprivation and excessive sleep, factors involved in the development of insomnia, as well as indications for its cures and treatments. KrygerCitation4,Citation5 referred to descriptions of sleep apnea in ancient Greek writings, and in the 19th century novelist Charles Dickens’ The Pickwick Papers; and both LavieCitation6,Citation7 and GuilleminaultCitation8 explored 19th century landmark reports of sleep apnea in the medical literature.

Clearly, sleep disorders are “nothing new under the moon”,Citation6 and the physiological and psychological mechanisms involved in their development remain similar throughout history. For example, Ancoli-IsraelCitation3 provides several quotes from the Bible regarding anxiety, stress and anguish in relation to sleeplessness; indeed, these are some of the same factors which are associated with the development of insomnia today.Citation9–Citation11

Nevertheless, factors that potentiate the mechanisms involved in the development of sleep disorders are closely related to the “zeitgeist”, ie, the sociocultural, technological and lifestyle trends which characterize an era. One salient demonstration of such factors refers to shift work, which has evolved from the 24/7 lifestyle enforced in modern societies. Shift work imposes a continuous misalignment between endogenous circadian (24-hour) rhythms and the environmental light/dark cycle. Such desynchrony in physiological and behavioral circadian rhythms has been shown to cause sleep loss and sleepiness, and to detrimentally affect mental performance, safety and health.Citation12,Citation13 Similar consequences may be found in cases of jet lag, yet another circadian rhythm disorder, which has become prevalent due to the vast expansion of transmeridian travel.Citation12,Citation14

Other modern lifestyle factors affecting sleep are also closely linked to advances in modern technology, enabling and indeed encouraging later bedtimes and longer hours of nighttime arousal; eg, electronic media devices such as television and computers.Citation15–Citation17 Yet other factors that interfere with normal sleep/wake patterns include substances such as caffeine, nicotine, alcohol, and drugs, which are commonly consumed in attempts either to maintain alertness and arousal, or to achieve sleepiness and tranquility.Citation15,Citation18–Citation23 Lifestyle changes in dietary and physical activity habits and the increased prevalence of overweight and obesity in modern society are also associated with sleep deprivation and disturbance.Citation24–Citation26

The aim of this review is to highlight current lifestyle trends that have been shown in scientific investigations to be associated with sleep patterns, sleep duration and sleep quality. Available therapies used to treat some lifestyle related sleep disorders will be discussed. Future perspectives will be provided for the investigation of lifestyle factors that are associated with poor sleep, in terms of understanding the underlying mechanisms, as well as establishing appropriate therapies and public health interventions for their treatment.

Lifestyle trends associated with altered sleep patterns

The following sections will provide a review of the available investigations suggesting associations between various current lifestyle factors and sleep disturbances. Underlying mechanisms as well as some of the consequences of sleep disturbances related to lifestyle factors will also be discussed.

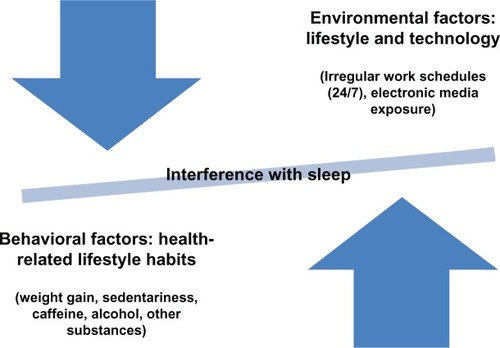

In an attempt to conceptualize these relationships, a hypothetical model is presented, elaborating the factors associated with chronic interference with sleep patterns in the modern world (see ). This model divides lifestyle factors into those that have emerged from environmental technological developments that disrupt normative sleep patterns, and those that may be viewed as behavioral habits, that may serve as countermeasures aimed to combat the deleterious consequences of sleep loss and sleepiness.

Figure 1 Schematic model conceptualizing the lifestyle factors that impinge on sleep, and distinguish between environmentally imposed technology-related lifestyle factors and behavioral lifestyle factors that may be considered as habits or countermeasures in response to environmental changes. Both categories ultimately create an imbalance in sleep quality, quantity and timing.

Technological developments and circadian desynchrony: alternative work schedules, jetlag, altered light exposure and electronic media

Shift work

In industrialized society, approximately 20% of the population works beyond the normative day shift, in various schedules of shift work.Citation12,Citation27–Citation29 Ample research has been done on the effects of shift work on sleep and related health and performance outcomes.Citation28,Citation30–Citation35

The characteristics of sleep in shift workers have been reviewed by Åkerstedt.Citation33 Night shift workers exhibit shortened subsequent daytime sleep, more objective and subjective measures of sleepiness, lasting for several days following the night shift, and are prone to falling asleep during the shift, particularly towards the early morning hours. Morning shift workers experience curtailed sleep due to early rise times and subsequent daytime sleepiness. Taken together, reduced sleep and excessive sleepiness in shift workers have been implicated as mediators of impaired safety, productivity, performance and health.Citation28,Citation29,Citation31,Citation36,Citation37

To understand why shift workers experience reduced sleep time and sleepiness, it is necessary to describe the human circadian timing system. Physiological and behavioral processes, including the secretion of hormones, the sleep/wake schedule and the performance of mental activities, are known to oscillate in circadian (about 24 hours) cycles that are controlled by the biological clock, located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus.Citation12,Citation38 Under normal conditions, circadian rhythms are entrained to the environmental light–dark cycle and are synchronized with it. Thus, time-of-day effects demonstrate increased sleep propensity and reduced alertness and performance capacity in the early morning hours, corresponding to the minimum in core body temperature, the peak of melatonin secretion and the timing of the habitual sleep phase.Citation39,Citation40 Changes in the timing of sleep and wake periods create circadian desynchrony. Shift workers on night or rotating shifts are required to remain awake during periods of increased sleep propensity; and the timing of their sleep phase is shifted to the daytime hours, when rhythms of performance, alertness and core body temperature are on the rise.Citation12,Citation39,Citation40 Daytime sleep is shorter, ensuing in partial sleep deprivation and sleepiness. Such chronic exposure to circadian desynchrony entails serious consequences, by compromising safety, productivity and health.Citation28,Citation37,Citation41 Some of the immediate consequences of shift work include increased risks for human error, accidents and injuries.Citation31,Citation37,Citation42

Shift Work Sleep Disorder (SWSD) has been defined by The International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 2nd editionCitation43 as the presence of insomnia and/or daytime sleepiness associated with shift work. In a study on its prevalence and characteristics, the true prevalence of SWSD was 14% in night shift workers and 8% in rotating shift workers, after removing the percentage of insomnia and excessive sleepiness found in day workers.Citation36 Those with SWSD had higher rates of ulcers and depression, missed more work days and more family/social events, and had higher scores of neuroticism and more sleepiness-related accidents, than their shift work counterparts who did not have SWSD. For most of these outcomes, workers with SWSD had increased morbidity in comparison to their day work counterparts with the same symptoms (ie, insomnia and daytime sleepiness without shiftwork). These findings demonstrate the additive effects of symptoms of poor sleep (insomnia, excessive sleepiness) and work schedule (circadian desynchrony) on serious health and functional outcomes.Citation12,Citation36

Cross sectional and longitudinal investigations indicate that shift workers are at an increased risk for developing health problems, including gastrointestinal and cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and metabolic disorders, breast and colon cancers.Citation12,Citation34,Citation41 Investigations on the mechanisms underlying these relationships suggest that sleep deprivation and circadian desynchrony are involved in changes in neuroendocrine function, reduced capacity of the immune system, metabolic disturbances and tumor growth.Citation34,Citation41,Citation44,Citation45 Exposure to light at night, leading to melatonin suppression, has also been implicated as an underlying mechanism (see below).

Flexible work systems

In addition to shift work, flexible work systems in which workers are not confined to traditional work hours have become increasingly prevalent.Citation27,Citation28 Flexibilization is a relatively new concept in organizational management, and is linked to trends in globalized economy.Citation46 Such nonstandard work schedules are highly variable among organizations, and may include working evenings, weekends, split shifts, on call hours or compressed work weeks.Citation27,Citation30 Though seemingly an attractive approach for allowing workers to tailor their work schedule to their individual needs,Citation47 flexible work schedules may have a negative impact on workers’ health.

In a study comparing traditional and nontraditional work schedules, scores of physical health, mental wellbeing and sleep quality were consistently higher for the traditional schedule workers.Citation30 Specifically, sleep quality was significantly lower in those working irregular shifts and compressed work weeks (10–12 hour 3–4 weekly shifts). Pending further investigation, the effects of flexible work systems on sleep and health may depend on workers’ degree of flexibility; ie, increasing workers’ control and choice of their work schedules may have beneficial effects on their sleep, health and overall wellbeing; whereas organizational enforced work schedules have a more negative impact on workers’ overall health.Citation48

Jet lag

Jet lag is another circadian rhythm disorder which has emerged vis a vis the widespread popularity of transmeridian travel in recent decades.Citation14 Circadian desynchrony between the sleep–wake schedule and other endogenous circadian rhythms with the environmental light–dark cycle creates symptoms of jet lag, including daytime sleepiness, difficulty falling asleep during eastward flights, early morning awakenings on westward flights, impaired alertness and performance as well as gastrointestinal problems and loss of appetite.Citation12

The circadian timing system is able to readjust to new environmental time cues. On average, the adaptation rate is an hour a day, so that, depending on the number of time zones crossed and individual differences, travelers can expect their circadian system to adapt to the new time zone, given that they remain at their destination for a sufficient amount of time.Citation12 However, when transmeridian travel is ongoing, such as in the case of aircrew cabin workers, chronic jet lag is associated with reduced cognitive capacities and higher levels of cortisol.Citation49 Furthermore, chronic jet lag simulated in laboratory mice is associated with dysregulation of the immune system, that is mediated by circadian desynchrony but not by sleep loss.Citation50 Future investigations may further elaborate on the long term effects of jet lag on sleep, performance and health.

Both jet lag and shift work represent disorders in which a circadian system functions properly under normal conditions, but cannot adjust under voluntary or imposed phase shifts. For evaluation and management purposes, they are collectively referred to as circadian rhythm sleep disorders (CRSDs)Citation51 (see treatment section).

Altered exposure to light

Light exposure plays a strong role in the circadian timing system. The resetting effects of light on the human circadian system have been described, demonstrating that timed exposure to bright light can create both a delay and an advance in the timing of circadian rhythms.Citation52,Citation53 Bright light during the night has also been found to have immediate effects on physiological and behavioral measures.Citation54 In comparison to dim light, bright light exposure decreased sleepiness, increased alertness, improved performance on behavioral tasks and attenuated the nightly drop in core body temperature. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that bright light may be used therapeutically to reset the circadian system, eg, in the case of jet lag; and to exert immediate effects of enhanced alertness in the context of nighttime shift work.

Indeed, light exposure has been shown to be a potent treatment for various circadian rhythm disorders (see section on treatment). However, accumulating lines of evidence point to the negative effects of exposure to light during the nighttime hours. Such exposure has become extremely common in various contexts in the modern world.

One line of evidence refers to nighttime light exposure as a risk factor for breast and prostate cancer.Citation55–Citation57 Epidemiological studies have shown an increased risk for breast cancer in women exposed to nighttime light in the home environment as well as in nightshift workers.Citation57,Citation58 Based on animal studies and human epidemiological studies, the light at night (LAN) theory implicates that circadian disruption and melatonin suppression by nighttime light exposure are the underlying mechanisms leading to tumor growth.Citation59,Citation60

Another line of evidence of the harmful effects of mistimed light exposure refers to a new concept, termed asynchronization, in children and adolescents.Citation61 This concept attempts to explain the high prevalence of insomnia and daytime sleepiness in children. Similar to the LAN theory, sleep is disrupted due to late night light exposure, causing circadian desynchrony and melatonin suppression. Also, lack of early morning light exposure prevents normal circadian entrainment to the environmental light/dark cycle. Future prospective intervention studies designed to enhance circadian entrainment in young individuals may provide support for the asynchronization model.

Finally, daylight savings time (DST), yet another relatively novel feature of modern society, has received little attention in the scientific literature. During the DST transitions in spring and autumn, social, but not environmental time cues shift abruptly, creating a one hour advance (in spring) and a one hour delay (in autumn) of the timing of dawn relative to the shifted social norms. In a study using pooled data of several western European countries, which aimed to assess the effects of DST on physiological and behavioral entrainment to the environment, investigators have found that sleep time adjusts to the seasonal progression of dawn during standard time, but not during DST.Citation62 Furthermore, when comparing morning and evening chronotypes, they found that sleep and activity rhythms fail to adjust to DST, particularly in evening chronotypes. Further investigations may assess the consequences of this failure to entrain during DST on measures of functioning and health.

Electronic media exposure

Associations between sleep patterns and electronic media exposure have been reported extensively in children and adolescentsCitation15,Citation17,Citation63–Citation68 as well as in adults.Citation66,Citation69 Overall, electronic media exposure in children and adolescents was most consistently associated with later bedtime and shorter sleep duration, and the presence of a media device in the bedroom was associated with increased exposure, later bedtime and shorter sleep.Citation16,Citation17,Citation63 In a 1-year prospective study of young men and women, looking at the psychological effects of exposure to various types of information and communication technologies (ICT), increased internet surfing for women, and increased cell phone calls and SMS messages for men, were found to increase the risk of developing sleep disturbances.Citation69

Attempts to conceptualize the underpinnings of these associations remain speculative. Van den BulckCitation16,Citation70 has referred to electronic media exposure as an unstructured and boundless leisure activity with no clear endpoints, unlike other hobbies or sports activities. Shochat and associatesCitation17 have suggested that a media device in the bedroom may indicate high availability of the device and low parental control, both leading to increased exposure. It has also been suggested that electronic media exposure may have alerting effects,Citation17,Citation70 possibly due to the suppression of melatonin by the bright light emanating from electronic screensCitation71 as well as due to their engaging and exciting content.

Cain and GradisarCitation68 have suggested a model designed to demonstrate putative factors mediating the effects of electronic media on sleep in young individuals. Based on this model, background variables such as age, socioeconomic status and parental control may impact the intensity of electronic media use, including the presence or absence of a media device in the bedroom. In turn, proposed mechanisms that lead to sleep disruption include a physiological delay in the circadian sleep/wake rhythm, as well as physiological, mental and cognitive excitement and arousal. Sleep disruption subsequently leads to impaired daytime functioning. Future lines of investigation may further validate these relationships via experimental and longitudinal designs.

Behavioral patterns and countermeasures of sleep disorders and sleepiness: weight gain, physical activity and use of substances

Weight gain

Levels of obesity and overweight have dramatically risen in developed and developing societies, reaching pandemic proportions in children and adults alike.Citation72,Citation73 In the past two decades the average level of obesity in OECD countries has risen by 8 percent.Citation74 In the United States in 2004, 17% of the child and adolescent population was overweight and one third of the adult population was obese.Citation75 These rates were significantly increased in children and adolescents and in adult males (but not women) compared to rates from 1999. The public health impact of obesity has been reviewed, linking obesity with type 2 diabetes, cancers, cardiovascular diseases, musculoskeletal disorders, respiratory disorders including sleep apnea, and all-cause mortality.Citation76

Environmental and behavioral changes have been implicated as the major factors responsible for weight gain,Citation72 particularly changes in dietary habits (ie, high fat, energy dense diets), reduced physical activities corresponding to increased sedentary activities, eg, television exposure,Citation77 as well as decreased duration of sleep.Citation72,Citation77–Citation84 Studies have investigated sleep as both a cause and a consequence of weight gain.

As part of a cross-sectional survey on health and nutrition in European teens, shorter sleep was associated with higher measures of obesity, including body mass index, waist circumference and body fat percentage.Citation81 Short sleepers reported more sedentary time, watched more television and maintained a less nutritional diet compared to adequate sleepers (≥8 hours of sleep per night). In a six year prospective study, a comparison of adiposity measures was made on adults who were short sleepers at baseline (≤6 hours per night), between those who remained short sleepers and those who increased their sleep to 7–8 hours per night. These groups were also compared to long (7–8 hours) sleepers both at baseline and at 6-year follow up. Both short sleeper groups had comparable adiposity measures at baseline, whereas at follow up, the short sleepers group increased body mass index and body mass, compared to the increased sleepers group, who showed similar measures to the long sleepers.Citation84

Possible mechanisms underlying the relationship between short sleep duration and obesity have been suggested. Studies have demonstrated that regulation of the hormones leptin and ghrelin, signaling satiety and appetite respectively, is disrupted due to sleep loss, resulting in increased hunger and appetite.Citation83,Citation85–Citation87 Furthermore, it has been shown that during television viewing, metabolic rate is lowCitation88 and metabolic risk is increased.Citation89 It has been suggested that increased television viewing leads to reduced sleep duration, which in turn leads to increased hunger and decreased metabolic rate, ultimately resulting in overweight and obesity.Citation78 However, in a critical review, Marshall and associatesCitation90 have concluded that there is insufficient and conflicting evidence regarding short sleep duration as a risk factor for obesity, and warned that advocacy of such a public health message is premature. Clearly, additional experimental and longitudinal studies are needed to determine possible causal pathways between these variables.

Conversly, obesity has been associated with an increased risk for sleep disordered breathing (SDB), both in children and adults.Citation91–Citation95 Tauman and GozalCitation91 have reviewed the evidence that obesity is a risk factor for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in children, and have suggested that in obese individuals low bioavailability of leptin, an important regulatory hormone of ventilatory mechanisms, may be a possible mediator. The authors further suggest that obstructive sleep apnea may in turn contribute to the strong links between obesity and comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease and the metabolic syndrome, possibly by amplifying inflammatory processes.

Nevertheless, obesity may not unequivocally be considered as a risk factor for SDB in young individuals.Citation96,Citation97 Kohler and van den HeuvelCitation97 have suggested that developmental stages as well as ethnic differences and their underlying anatomic and genetic predispositions are likely to be important moderators in this relationship. It may be concluded, that while obesity and SDB have many common clinical features and likely interact reciprocally, much investigation is needed to further understand the underpinnings of their relationship.Citation96,Citation97

Finally, it is noteworthy that studies have found an increased prevalence of insomnia in adults with SDB.Citation98,Citation99 Of a random sample of patients diagnosed with SDB, Krakow and associatesCitation99 found that 50% also had clinically significant signs of insomnia, and that those patients with both SDB and insomnia had more medical and psychiatric disorders and consumed more sedatives and psychotropic medications compared to SDB patients without insomnia. Whereas causal relationships between SDB and insomnia are at present speculative, it may be assumed that SDB contributes to the development of insomnia via sleep fragmentation.Citation98 Inasmuch as rates of SDB have increased, in part due to the increase in weight gain,Citation91,Citation94 SDB may be considered as a lifestyle-related medical condition that is associated with insomnia. Whether weight gain itself is also associated with insomnia is yet to be determined.

Physical activity

Epidemiological studies have established that levels of physical activity (PA) are low in US adolescents and adults, and that PA declines and inactivity increases between adolescence and young adulthood.Citation100,Citation101 Yet investigations focusing on the relationship between sleep and physical activity, exercise, and inactivity in the community are few. Different PA protocols and measures, as well as individual differences in age, gender, and fitness obscure the ability to support the underlying assumption that exercise promotes sleep.Citation102 In patients with sleep apnea, a tendency towards an inverse relationship between PA and the respiratory disturbance index (RDI) was demonstrated, ie, higher PA was associated with a lower RDI.Citation103 Findings from the Sleep Heart Health Study (SHHS)Citation104 have shown that vigorous PA performed at least 3 hours weekly was associated with a reduced risk for SDB, particularly in obese men. Clinical prospective protocols are warranted to assess the feasibility and efficacy of applying PA in intervention programs for SDB. In older adults, PA has been found to be a protective factor for incident and persistent late life insomnia.Citation105 Yet in a study assessing sleep and PA using actigraphic (activity monitor) measures in 8-year-old children, a bidirectional inverse relationship was found, showing that increased PA during the day was associated with lower subsequent nighttime sleep quality, and improved nighttime sleep measures were related to lower levels of PA on the following day. Citation106 Clearly, further investigations must be done to identify developmental changes and to clarify the underlying mechanisms in the relationship between PA and sleep.

Caffeine, alcohol and other health risk substances

In a recent nationally representative epidemiological study in high school students in the United States, insufficient sleep (<8 hours/per night) was reported by over two thirds of the students.Citation107 Strong associations were found between insufficient sleep and several prevalent health risk behaviors, including current use of alcohol (46%), smoking cigarettes (21%) and marijuana (21%), being sexually active (36%), being involved in a physical fight (35%), low PA (66%), increased sedentary activities (TV ≥ 3 hours [36%], computers ≥ 3 hours [25%], see section on electronic media above) and signs of depressed mood (28%). Earlier epidemiologic studies have also reported that sleep problems and an evening tendency in adolescents were associated with the use of alcohol, caffeine, cigarettes, and illicit drugs.Citation108,Citation109 Psychiatric problems generally modified these associations, with the exception of illicit drugs and sleep problems, which were unrelated to psychiatric problems.Citation108

Given the high prevalences of both insuffucient/disturbed sleep and the use of health-risk substances, it is imperative to understand the underlying mechanisms of these associations, in order to develop appropriate public health interventions. In this section, findings on relationships between sleep disturbances and caffeine, alcohol and cigarette smoking will be discussed, as these health risk substances have been the main focus of investigation in relation to sleep disturbances.

Caffeine

Caffeine is a widely consumed psychoactive substance. As an adenosine antagonist, caffeine has been shown to attenuate electroencephalographic markers associated with the decrease of homeostatic sleep pressure.Citation110 Caffeine has been shown to combat sleepiness and to restore alertness and performance in experimental designs; however, habitual daily caffeine consumption has been related to sleep disruption and sleepiness.Citation111 Evening consumption of caffeine has been shown to increase sleep latency and decrease sleep duration, sleep efficiency and stage 2 sleep in young and middle-aged adults.Citation112

Caffeinated beverages have become increasingly popular among young individuals. Based on an epidemiologic study of over 7000 Icelandic 9th and 10th graders, 76% reported daily consumption,Citation19 as was found in the United States poll of the National Sleep Foundation.Citation113 Such a high prevalence greatly exceeds the lifetime prevalence of alcohol (56%) or nicotine use (28%) in the adolescent population.Citation19 Though seemingly benign, caffeine consumption was independantly associated with increased daytime sleepiness and decreased academic performance, and substantially contributed to the negative relationships between nicotine and alcohol use and academic performance.Citation19

Increased nightly caffeine consumption has also been associated with increased multitasking of electronic media devices prior to bedtime in middle and high school students.Citation15 Students who both multitasked and consumed caffeine were 70% more likely to fall asleep at school, and 20% more likely to report difficulty falling asleep on school nights.

In a survey exploring patterns as well as reasons and expectations of caffeine consumption among adolescents, 95% of a high school sample consumed caffeine within the 2 weeks of the survey.Citation18 Students reported drinking mostly caffeinated sodas, followed by coffee, with highest consumption rates in the evening hours. High caffeine consumers who drank both sodas and coffee reported more dependence issues, had higher expectations regarding caffeine as an energy enhancer and a substance that gets them through the day, and reported more daytime sleepiness compared to the lower caffeine consumers. Nevertheless, adolescents in this sample generally showed little concern with any of the effects of caffeine use, possibly indicating that they are simply unaware of these effects.

While most studies have focused on the effects of moderate levels of caffeine consumed in coffee and/or caffeinated soft drinks, few have focused on energy drinks, which are a fast growing segment of the beverage market and are particularly popular among youth.Citation114 The content of caffeine in these drinks ranges between 50–500 mg per can or bottle. Findings from the Icelandic study showed that 38% of the daily caffeine consumers drank energy drinks, following 66% who were cola drinkers.Citation19

The acute and long term effects of energy drinks on health and performance are largely unknown;Citation114 however, reports of caffeine intoxication suggest that these drinks may increase problems of caffeine dependance and withdrawal as well as use of other drug substances. Longitudinal studies assessing the effects of energy drinks on sleep are warranted, taking into consideration not only differences in caffeine content and additional ingredients, but also looking at differences in drinking and sleeping patterns on weekdays versus weekends, as well as possible demographic mediating factors such as age, gender, socioeconomic status and culture.

Alcohol

The use of alcohol in young individuals has been shown to increase over time. In a recent study from the Netherlands comprised of two cohorts (1993, 2005–2008) and of 3 age groups (13–15, 16–17 and 18–21), the prevalence of alcohol initiation increased, particularly in the youngest age group (from 63% in 1993 to 74% in 2005–2008). Quantities of alcohol consumption also increased significantly between cohorts.Citation115

The effects of alcohol on sleep are well documented. Based on PSG recordings in young adults, evening consumption of a high alcohol dose (breath alcohol concentration [BrAC] 0.10) reduced sleep latency and efficiency and increased wake time throughout the night.Citation116 Sleep consolidation was high during the first half of the night, and decreased during the second half. Subjective sleepiness increased, and sleep quality ratings decreased. These effects were more pronounced for women. Beyond its effects on sleep, alcohol created hangover and reduced performance on tasks requiring sustained attention and speed on the following morning.Citation117

As alcohol consumption often begins in early adolescence, and as sleep disturbances are highly prevalent in this age group, Pieters and associatesCitation118 sought to investigate possible mediators of the relationship between the two. They found that puberty was related to alcohol use directly, but also indirectly, via sleep problems and delayed phase preference that typically begins in early adolescence. It was concluded that puberty-related changes in sleep regulation may underlie the vulnerability of young adolescents to alcohol consumption. In a prospective study of children of alcoholics, sleep problems in early childhood predicted substance use in adolescence, particularly in boys.Citation119 Whether these finding generalize to children of parents free of substance abuse may be determined in future prospective investigations.

Cigarette smoking

Cigarette smoking has been recognized as a behavior that interferes with sleep. Laboratory and survey studies have reported that adult smokers experience more difficulty falling asleep and more sleep fragmentation than non smokers, probably due to the stimulant effects of nicotine.Citation120–Citation122 In a study assessing smoking patterns and sleep quality, night smokers had a higher prevalence of poor sleep and reported more sleep disturbances than non-night smokers.Citation123 Sleep duration was considerably shorter in night smokers who had poor sleep, compared to poor sleepers who did not smoke at night. Furthermore, night smoking and sleep disturbances both increased the risk of smoking cessation failure.

In smokers compared to nonsmokers, a higher prevalence of sleep bruxism has been reported.Citation124 However, no differences have been found for either restless legs syndrome (RLS) and periodic limb movements in sleep (PLMS),Citation124 or respiratory disturbances in healthy individuals.Citation125

Although general trends across cohorts demonstrate a substantial reduction in the prevalence of cigarette smoking and increased smoking cessation, adolescents and young adults constitute the most vulnerable age range for smoking initiation.Citation126,Citation127 In adolescents, cigarette smoking has been associated with an evening preference and with early puberty.Citation109,Citation128 In a survey on perceptions of sleep in high school adolescents, 6% of the entire sample reported that they smoke as a means to help them fall asleep.Citation129 In a prospective 2 wave study of insomnia and risk taking behaviors, the presence of insomnia predicted smoking within each wave, but not longitudinally.Citation130 Clearly, more prospective studies are needed to understand the direction of this relationship and how it may change developmentally.

Treatment of lifestyle and technology related sleep disturbances

The development of treatment strategies designed for specific lifestyle related sleep disturbances have largely focused on the treatment of circadian rhythm sleep disorders, ie, shift work and jet lag. Few interventions have been developed for other environmental and behavioral lifestyle factors affecting sleep, such as electronic media exposure, physical activity, weight gain and substance use. For standard guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of sleep disorders, readers are referred to the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 2nd edition.Citation43

Treatment of circadian rhythm sleep disorders (CRSD) and altered light exposure

Shift work and jet lag are treated based on guidelines for the treatment of CRSD,Citation51 which include prescribed sleep scheduling, phase shifting with light exposure and/or melatonin (and its agonist) administration, and symptomatic treatments to combat insomnia and excessive sleepiness.

Prescribed sleep scheduling refers to changes in sleep and wake timing that are designed to optimize sleep quality during the sleep period and alertness during the wake period. “Chronotherapy” refers to treatment that is optimized by application based on oscillations of the circadian timing system. It was initially introduced to treat individuals with delayed sleep phase by gradual delay of sleep episodes until achieving a desired sleep phase.Citation131 Chronotherapy and chronopharmacy have been under investigation for application in the treatment of cancersCitation132 as well as hypertension and asthma.Citation133,Citation134 In shift workers, investigations assessing optimal shift schedules based on chronobiological principles have suggested that clockwise rotation is more beneficial to workers than counterclockwise rotation, in terms of adaptation, health and wellbeing.Citation41,Citation135

Another sleep scheduling strategy is planned napping either prior to or during the work shift, aimed to offset the immediate effects of sleepiness on performance during the nightshift.Citation136,Citation137 These and other studies have demonstrated that short naps of 20–40 minutes were sufficient to improve alertness and performance measures during the night.

The circadian resetting and immediate alerting effects of light exposure have been described (see section on altered exposure to light). Though well-established, the applicability of achieving the effects of light to counter nighttime sleepiness in shift workers has been hampered by investigations demonstrating that nighttime light exposure and its suppressant effect on melatonin production may be the cause of an increased risk of tumor growth in animal studies.Citation138 However, investigational efforts to overcome this untoward effect, eg, by filtering low wavelength light, which suppresses melatonin, without compromising the positive effects of light on alertness and performance,Citation139 may lead to revised guidelines for safe and efficient exposure to bright light during the night shift. Avoidance of early morning bright light on the ride home from work has also been found to be beneficial to allow a smoother transition to the morning sleep period.Citation140 For jet lag, appropriately timed light exposure at the destination of travel has also been found to be beneficial.Citation141 Westward travelers may benefit from evening light exposure and avoiding morning light exposure at their destination; while eastward travelers should avoid evening light and be exposed to morning light, in order to achieve an advanced sleep phase.

To improve sleep in CRSD, melatonin and its agonist as well as sleep medications are recommended prior to the desired sleep time. However, sedating medications should be used with caution when used during the day, as they compromise alertness, safety and performance. Conversely, wake-promoting agents, modafinil and armodafinil, have proven effective for increasing alertness and performance during shift work.Citation141

Finally, maintenance of sleep hygiene practices, such as achieving an adequate amount of sleep, sleeping in a dark and quiet environment and controlling caffeine and alcohol consumption, are recommended for the treatment of insomnia related to CRSD.Citation12,Citation51

Behavioral lifestyle factors

While intervention studies aimed to modify health related lifestyle behaviors (eg, weight gain, sedentary activity and substance use) have shown some positive outcomes, few have reported sleep as a major outcome.

Randomized clinical trials have demonstrated that weight reduction has a significant impact on OSA.Citation142,Citation143 In overweight individuals with mild OSA, a lifestyle intervention with a very low calorie diet significantly reduced body weight and apnea/hypopnea index (AHI), and improved related symptoms and measures of quality of life.Citation143 Similar findings were found for overweight individuals with moderate to severe OSA.Citation142 Improvements were maintained at the 1 year follow-up in both studies.

Exercise interventions have shown some benefits in sleep quality for clinical populationsCitation144,Citation145 and postmenopausal women.Citation146 Tai Chi, a traditional Chinese exercise of low to moderate intensity has shown positive benefits on sleep quality and daytime sleepiness in older adults.Citation147,Citation148 Aerobic exercise has been shown to decrease symptoms of sleep disordered breathing in overweight children.Citation149

In a public health intervention aimed at enhancing multiple health behaviors in high school adolescents,Citation150 positive outcomes included reductions in alcohol use and increases in fruit and vegetable consumption and participation in relaxation activities. Sleep measures, exercise, cigarette and marijuana use remained unchanged. Health education interventions specifically targeting adolescent sleep problems have shown that despite improvements in sleep knowledge and motivation, no behavioral changes in sleep practices were achieved.Citation151,Citation152 However, in a recent cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) intervention on school-aged children, significant improvements were found in sleep measures such as sleep latency, sleep efficiency and wake time after sleep onset, and were maintained at follow-up.Citation153

In summary, interventions aimed at improving sleep disturbances that are related to specific behavioral lifestyle habits are only beginning to emerge. It is interesting to note that conversely, sleep extension has been recommended as an intervention to avoid weight gain and allow weight loss, particularly in young individuals;Citation83,Citation154,Citation155 however, to date, outcome studies have yet to be reported.

Future perspectives

Despite ample evidence of the associations between lifestyle health behaviors and sleep quality, a comprehensive understanding of the causal relationships may be difficult to achieve. Lifestyle, technology and health behaviors including sleep are all intertwined and strongly embedded in the cultural and social environment. Prospective and longitudinal investigations following sleep patterns and related lifestyle behaviors are needed, to attempt to tease apart some of these variables and establish the temporal order of events. Such studies may also incorporate demographic, psychosocial and biological inter-individual differences, to develop mediating models and to establish possible underlying mechanisms.

The development of public health interventions targeting specific lifestyle behaviors associated with poor sleep, tailored for different age groups, are warranted. Electronic media exposure, eating, and physical activity habits in children; risk behaviors and appropriately timed light exposure in adolescents and young adults are some examples.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- AserinskyEKleitmanNRegularly occurring periods of eye motility, and concomitant phenomena, during sleepScience1953118306227327413089671

- DementWKleitmanNCyclic variations in EEG during sleep and their relation to eye movements, body motility, and dreamingElectroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol19579467369013480240

- Ancoli-IsraelSSleep is not tangible” or what the Hebrew tradition has to say about sleepPsychosom Med200163577878711573026

- KrygerMHSleep apnea: From the needles of Dionysius to continuous positive airway pressureArch Intern Med198314312230123036360064

- KrygerMHFat, sleep, and Charles Dickens: Literary and medical contributions to the understanding of sleep apneaClin Chest Med1985645555623910333

- LaviePNothing new under the moon. historical accounts of sleep apnea syndromeArch Intern Med198414410202520286385898

- LaviePWho was the first to use the term Pickwickian in connection with sleepy patients? History of sleep apnoea syndromeSleep Med Rev200812151718037311

- GuilleminaultCObstructive sleep apnea. The clinical syndrome and historical perspectiveMed Clin North Am1985696118712033906300

- StepanskiEJRybarczykBEmerging research on the treatment and etiology of secondary or comorbid insomniaSleep Med Rev200610171816376125

- ShochatTDaganESleep disturbances in asymptomatic BRCA1/2 mutation carriers: women at high risk for breast–ovarian cancerJ Sleep Res201019233334020337906

- EspieCABroomfieldNMMacMahonKMacpheeLMTaylorLMThe attention-intention-effort pathway in the development of psychophysiologic insomnia: a theoretical reviewSleep Med Rev200610421524516809056

- RajaratnamSMWArendtJHealth in a 24-h societyThe Lancet200135892869991005

- ScheerFAJLHiltonMFMantzorosCSSheaSAAdverse metabolic and cardiovascular consequences of circadian misalignmentProc Natl Acad Sci USA200910611445319255424

- WaterhouseJReillyTAtkinsonGJet-lagLancet19973509091161116169393352

- CalamaroCJMasonTRatcliffeSJAdolescents living the 24/7 lifestyle: Effects of caffeine and technology on sleep duration and daytime functioningPediatrics20091236e1005e101019482732

- Van den BulckJTelevision viewing, computer game playing, and internet use and self-reported time to bed and time out of bed in secondary-school childrenSleep200427110110414998244

- ShochatTFlint-BretlerOTzischinskyOSleep patterns, electronic media exposure and daytime sleep-related behaviours among Israeli adolescentsActa Pædiatrica201099913961400

- Bryant LuddenAWolfsonARUnderstanding adolescent caffeine use: connecting use patterns with expectancies, reasons, and sleepHealth Educ Behav201037333034219858312

- JamesJEKristjánssonÁLSigfúsdóttirIDAdolescent substance use, sleep, and academic achievement: evidence of harm due to caffeineJ Adolesc201134466567320970177

- ShibleyHLMalcolmRJVeatchLMAdolescents with insomnia and substance abuse: consequences and comorbiditiesJ Psychiatr Pract200814314615318520783

- SteinMDFriedmannPDDisturbed sleep and its relationship to alcohol useSubst Abus200526111316492658

- ObermeyerWHBencaRMEffects of drugs on sleepOtolaryngol Clin North Am199932228930210385538

- JaehneALoesslBBárkaiZRiemannDHornyakMEffects of nicotine on sleep during consumption, withdrawal and replacement therapySleep Med Rev200913536337719345124

- ChaputJPSjödinAMAstrupADesprésJPBouchardCTremblayARisk factors for adult overweight and obesity: the importance of looking beyond the ‘big two’Obes Facts20103532032720975298

- MozaffarianDHaoTRimmEBWillettWCHuFBChanges in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and menN Engl J Med2011364252392240421696306

- PeppardPEYoungTPaltaMDempseyJSkatrudJLongitudinal study of moderate weight change and sleep-disordered breathingJAMA2000284233015302111122588

- BeersTMFlexible schedules and shift work: Replacing the 9-to-5 workday? Monthly Labor Rev20001233340

- CostaGShift work and occupational medicine: An overviewOccup Med (Lond)2003532838812637591

- GordonNPClearyPDParkerCECzeislerCAThe prevalence and health impact of shiftworkAm J Public Health19867610122512283752325

- MartensMNijhuisFVan BoxtelMKnottnerusJFlexible work schedules and mental and physical health. A study of a working population with non-traditional working hoursJ Organ Behav19992013546

- SmithLFolkardSPooleCIncreased injuries on night shiftLancet19943448930113711397934499

- Van DongenHPAShift work and inter-individual differences in sleep and sleepinessChronobiol Int20062361139114717190701

- ÅkerstedtTShift work and disturbed sleep/wakefulnessOccup Med20035328994

- KnutssonAHealth disorders of shift workersOccup Med2003532103108

- ÅkerstedtTWrightKPJrSleep loss and fatigue in shift work and shift work disorderSleep Med Clin20094225727120640236

- DrakeCLRoehrsTRichardsonGWalshJKRothTShift work sleep disorder: prevalence and consequences beyond that of symptomatic day workersSleep20042781453146215683134

- FolkardSTuckerPShift work, safety and productivityOccup Med200353295101

- KleinDCMooreRYReppertSMSuprachiasmatic Nucleus: The mind’s ClockNew YorkOxford University Press1991

- DijkDJDuffyJFRielEShanahanTLCzeislerCAAgeing and the circadian and homeostatic regulation of human sleep during forced desynchrony of rest, melatonin and temperature rhythmsJ Physiol1999516Pt 261162710087357

- JohnsonMDuffyJDijkDRondaJDyalCCzeislerCShort-term memory, alertness and performance: a reappraisal of their relationship to body temperatureJ Sleep Res199211242910607021

- HausESmolenskyMBiological clocks and shift work: circadian dysregulation and potential long-term effectsCancer Causes Control200617448950016596302

- SmithRKushidaCRisk of fatal occupational injury by time of daySleep200023 Suppl 2A110A111

- American Academy of Sleep MedicineThe International Classification of Sleep Disorders: Diagnostic and Coding Manual2nd ed.Westchester, ILAmerican Academy of Sleep Medicine2005

- HausESmolenskyMHBiologic rhythms in the immune systemChronobiol Int199916558162210513884

- BoggildHKnutssonAShift work, risk factors and cardiovascular diseaseScand J Work Environ Health1999252859910360463

- OechslerWWorkplace and workforce 2000+ -the future of our work environmentInt Arch Occup Environ Health200073 SupplS28S3210968558

- HallDTParkerVAThe role of workplace flexibility in managing diversityOrgan Dyn1993221518

- JoyceKPabayoRCritchleyJABambraCFlexible working conditions and their effects on employee health and wellbeingCochrane Database Syst Rev20102CD00800920166100

- ChoKEnnaceurAColeJCSuhCKChronic jet lag produces cognitive deficitsJ Neurosci2000206RC6610704520

- Castanon-CervantesOWuMEhlenJCDysregulation of inflammatory responses by chronic circadian disruptionJ Immunol2010185105796580520944004

- SackRLAuckleyDAugerRRCircadian rhythm sleep disorders: Part I, basic principles, shift work and jet lag Disorders. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine reviewSleep200730111460148318041480

- CzeislerCAAllanJSStrogatzSHBright light resets the human circadian pacemaker independent of the timing of the sleep-wake cycleScience198623347646676713726555

- MinorsDSWaterhouseJMWirz-JusticeAA human phase-response curve to lightNeurosci Lett1991133136401791996

- BadiaPMyersBBoeckerMCulpepperJHarshJBright light effects on body temperature, alertness, EEG and behaviorPhysiol Behav19915035835881801013

- ReiterRJTanDXErrenTCFuentes-BrotoLParedesSDLightmediated perturbations of circadian timing and cancer risk: a mechanistic analysisIntegr Cancer Ther20098435436020042411

- StevensRGWorking against our endogenous circadian clock: Breast cancer and electric lighting in the modern worldMutat Res20096801–210610820336819

- HansenJStevensRGCase-control study of shift-work and breast cancer risk in Danish nurses: Impact of shift systemsEur J Cancer201110.1016/j.ejca.2011.07.005

- KloogIStevensRGHaimAPortnovBANighttime light level co-distributes with breast cancer incidence worldwideCancer Causes Control201021122059206820680434

- KantermannTRoennebergTIs light-at-night a health risk factor or a health risk predictor? Chronobiol Int20092661069107419731106

- ReiterRJTanDXKorkmazALight at night, chronodisruption, melatonin suppression, and cancer risk: A reviewCrit Rev Oncog200713430332818540832

- KohyamaJSleep health and asynchronizationBrain and Development201133325225920937552

- KantermannTJudaMMerrowMRoennebergTThe human circadian clock’s seasonal adjustment is disrupted by daylight saving timeCurr Biol200717221996200017964164

- OwensJMaximRMcGuinnMNobileCMsallMAlarioATelevision-viewing habits and sleep disturbance in school childrenPediatrics19991043e2710469810

- Van den BulckJTelevision viewing, computer game playing, and internet use and self-reported time to bed and time out of bed in secondary-school childrenSleep200427110110414998244

- Van den BulckJAdolescent use of mobile phones for calling and for sending text messages after lights out: Results from a prospective cohort study with a one-year follow-upSleep20073091220122317910394

- SuganumaNKikuchiTYanagiKUsing electronic media before sleep can curtail sleep time and result in self-perceived insufficient sleepSleep Biol Rhythms200753204214

- LiSJinXWuSJiangFYanCShenXThe impact of media use on sleep patterns and sleep disorders among school-aged children in chinaSleep200730336136717425233

- CainNGradisarMElectronic media use and sleep in school-aged children and adolescents: A reviewSleep Med201011873574220673649

- ThoméeSEklofMGustafssonENilssonRHagbergMPrevalence of perceived stress, symptoms of depression and sleep disturbances in relation to information and communication technology (ICT) use among young adults-an explorative prospective studyComput Hum Behav200723313001321

- Van den BulckJThe effects of media on sleepAdolesc Med State Art Rev2010213418429 vii21302852

- HiguchiSMotohashiYLiuYAharaMKanekoYEffects of VDT tasks with a bright display at night on melatonin, core temperature, heart rate, and sleepinessJ Appl Physiol20039451773177612533495

- World Health OrganizationObesity: Preventing and Managing the Global EpidemicWorld Health Organization2000 Available from: http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/obesity/WHO_TRS_894/en/

- DeckelbaumRJWilliamsCLChildhood obesity: The health issueObes Res20019 Suppl 4239S243S11707548

- BleichSCutlerDMMurrayCAdamsAWhy is the Developed World Obese?2007National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper Series, No 12954 Available from: http://www.nber.org/papers/w12954

- OgdenCLCarrollMDCurtinLRMcDowellMATabakCJFlegalKMPrevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004JAMA2006295131549155516595758

- VisscherTLSSeidellJCThe public health impact of obesityAnnu Rev Public Health20012235537511274526

- GortmakerSLMustASobolAMPetersonKColditzGADietzWHTelevision viewing as a cause of increasing obesity among children in the United States, 1986–1990Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med199615043563628634729

- WellsJCHallalPCReichertFFMenezesAMAraujoCLVictoraCGSleep patterns and television viewing in relation to obesity and blood pressure: Evidence from an adolescent Brazilian birth cohortInt J Obes200832710421049

- PatelSRHuFBShort sleep duration and weight gain: A systematic reviewObesity (Silver Spring)200816364365318239586

- Van CauterEKnutsonKLSleep and the epidemic of obesity in children and adultsEur J Endocrinol2008159 Suppl 1S59S6618719052

- GarauletMOrtegaFRuizJShort sleep duration is associated with increased obesity markers in European adolescents: effect of physical activity and dietary habits. The HELENA studyInt J Obe (Lond)2011351013081317

- ChaputJPDesprésJPBouchardCTremblayAShort sleep duration is associated with reduced leptin levels and increased adiposity: results from the Québec family studyObesity (Silver Spring)200715125326117228054

- LeproultRVan CauterERole of sleep and sleep loss in hormonal release and metabolismEndocr Dev201017112119955752

- ChaputJDesprésJBouchardCTremblayALonger sleep duration associates with lower adiposity gain in adult short sleepersInt J Obes (Lond)2011 10.1038/ijo.2011.110 [Epub ahead of print.]

- SpiegelKLeproultRVan CauterEImpact of sleep debt on metabolic and endocrine functionLancet199935491881435143910543671

- SpiegelKLeproultRL’Hermite-BalériauxMCopinschiGPenevPDVan CauterELeptin levels are dependent on sleep duration: Relationships with sympathovagal balance, carbohydrate regulation, cortisol, and thyrotropinJ Clin Endocrinol Metab200489115762577115531540

- TaheriSLinLAustinDYoungTMignotEShort sleep duration is associated with reduced leptin, elevated ghrelin, and increased body mass indexPLoS Med200413e6215602591

- KlesgesRCSheltonMLKlesgesLMEffects of television on metabolic rate: Potential implications for childhood obesityPediatrics19939122812868424001

- EkelundUBrageSFrobergKTV viewing and physical activity are independently associated with metabolic risk in children: the European Youth Heart StudyPLoS Medicine2006312e48817194189

- MarshallNSGlozierNGrunsteinRRIs sleep duration related to obesity? A critical review of the epidemiological evidenceSleep Med Rev200812428929818485764

- TaumanRGozalDObesity and obstructive sleep apnea in childrenPaediatr Respir Rev20067424725917098639

- ShahNRouxFThe relationship of obesity and obstructive sleep apneaClin Chest Med200930345546519700044

- VerhulstSLVan GaalLDe BackerWDesagerKThe prevalence, anatomical correlates and treatment of sleep-disordered breathing in obese children and adolescentsSleep Med Rev200812533934618406637

- YoungTPeppardPETaheriSExcess weight and sleep-disordered breathingJ Appl Physiol20059941592159916160020

- YoungTShaharENietoFJPredictors of sleep-disordered breathing in community-dwelling adults: the Sleep Heart Health StudyArch Intern Med2002162889390011966340

- SpruytKGozalDMr. Pickwick and his child went on a field trip and returned almost empty handed…what we do not know and imperatively need to learn about obesity and breathing during sleep in children!Sleep Med Rev200812533533818790409

- KohlerMJvan den HeuvelCJIs there a clear link between overweight/obesity and sleep disordered breathing in children? Sleep Med Rev200812534736118790410

- LaviePInsomnia and sleep-disordered breathingSleep Med20078 Suppl 4S21S2518346673

- KrakowBMelendrezDFerreiraEPrevalence of insomnia symptoms in patients with sleep-disordered breathingChest200112061923192911742923

- JonesADAinsworthBECroftJBMaceraCALloydEEYusufHRModerate leisure-time physical activity: Who is meeting the public health recommendations? A national cross-sectional studyArch Fam Med1998732852899596466

- Gordon-LarsenPNelsonMCPopkinBMLongitudinal physical activity and sedentary behavior trends: adolescence to adulthoodAm J Prev Med200427427728315488356

- DriverHSTaylorSRExercise and sleepSleep Med Rev20004438740212531177

- HongSDimsdaleJEPhysical activity and perception of energy and fatigue in obstructive sleep apneaMed Sci Sports Exerc20033571088109212840627

- QuanSFO’ConnorGTQuanJSAssociation of physical activity with sleep-disordered breathingSleep Breath200711314915717221274

- MorganKDaytime activity and risk factors for late-life insomniaJ Sleep Res200312323123812941062

- PesonenAKSjösténNMMatthewsKATemporal associations between daytime physical activity and sleep in childrenPLoS One201168e2295821886770

- McKnight-EilyLREatonDKLowryRCroftJBPresley-CantrellLPerryGSRelationships between hours of sleep and health-risk behaviors in US adolescent studentsPrev Med2011534–527127321843548

- JohnsonEOBreslauNSleep problems and substance use in adolescenceDrug Alcohol Depend20016411711470335

- GiannottiFCortesiFSebastianiTOttavianoSCircadian preference, sleep and daytime behaviour in adolescenceJ Sleep Res200211319119912220314

- LandoltHPReteyJVTonzKCaffeine attenuates waking and sleep electroencephalographic markers of sleep homeostasis in humansNeuropsychopharmacology200429101933193915257305

- RoehrsTRothTCaffeine: sleep and daytime sleepinessSleep Med Rev200812215316217950009

- DrapeauCHamel-HebertIRobillardRÉBSelmaouiBFilipiniDCarrierJChallenging sleep in aging: the effects of 200 mg of caffeine during the evening in young and middle-aged moderate caffeine consumersJ Sleep Res200615213314116704567

- National Sleep Foundation (NSF) 2006 Sleep in America poll: Summary of findings2006Washington DCNational Sleep Foundation

- ReissigCJStrainECGriffithsRRCaffeinated energy drinks – a growing problemDrug Alcohol Depend2009991–311018809264

- GeelsLMBartelsMvan BeijsterveldtTCEMTrends in adolescent alcohol use: effects of age, sex and cohort on prevalence and heritabilityAddiction201110.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03612.x [Epub ahead of print.]

- ArnedtJTRohsenowDJAlmeidaABSleep following alcohol intoxication in healthy, young adults: effects of sex and family history of alcoholismAlcohol Clin Exp Res201135587087821323679

- RohsenowDJHowlandJArnedtJTIntoxication with bourbon versus vodka: Effects on hangover, sleep, and next-day neurocognitive performance in young adultsAlcohol Clin Exp Res201034350951820028364

- PietersSVan Der VorstHBurkWJWiersRWEngelsRCMEPuberty-dependent sleep regulation and alcohol use in early adolescentsAlcohol Clin Exp Res20103491512151820569245

- WongMMBrowerKJZuckerRAChildhood sleep problems, early onset of substance use and behavioral problems in adolescenceSleep Med200910778779619138880

- WetterDWYoungTBThe relation between cigarette smoking and sleep disturbancePrev Med19942333283348078854

- SoldatosCRKalesJDScharfMBBixlerEOKalesACigarette smoking associated with sleep difficultyScience198020744305515537352268

- ZhangLSametJCaffoBPunjabiNMCigarette smoking and nocturnal sleep architectureAm J Epidemiol2006164652953716829553

- PetersENFucitoLMNovosadCTollBAO’MalleySSEffect of night smoking, sleep disturbance, and their co-occurrence on smoking outcomesPsychol Addict Behav201125231231921443301

- LavigneGLLobbezooFRompréPHNielsenTAMontplaisirJCigarette smoking as a risk factor or an exacerbating factor for restless legs syndrome and sleep bruxismSleep19972042902939231955

- CasasolaGGÁlvarez-SalaJLMarquesJASánchez-AlarcosJMFTashkinDPEspinósDCigarette smoking behavior and respiratory alterations during sleep in a healthy populationSleep Breath200261192411917260

- BirkettNJTrends in smoking by birth cohort for births between 1940 and 1975: A reconstructed cohort analysis of the 1990 Ontario health surveyPrev Med19972645345419245676

- SchepisTSRaoUEpidemiology and etiology of adolescent smokingCurr Opin Pediatr200517560761216160535

- NegriffSDornLDPabstSRSusmanEJMorningness/eveningness, pubertal timing, and substance use in adolescent girlsPsychiatry Res2011185340841320674040

- NolandHPriceJHDakeJTelljohannSKAdolescents’ sleep behaviors and perceptions of sleepJ Sch Health200979522423019341441

- CatrettCDGaultneyJFPossible insomnia predicts some risky behaviors among adolescents when controlling for depressive symptomsJ Genet Psychol2009170428730920034186

- CzeislerCARichardsonGSColemanRMChronotherapy: resetting the circadian clocks of patients with delayed sleep phase insomniaSleep1981411217232967

- LeviFCircadian chronotherapy for human cancersLancet Oncol20012530731511905786

- HermidaRCAyalaDEFernandezJRCalvoCChronotherapy improves blood pressure control and reverts the nondipper pattern in patients with resistant hypertensionHypertension2008511697617968001

- PincusDJHumestonTRMartinRJFurther studies on the chronotherapy of asthma with inhaled steroids: The effect of dosage timing on drug efficacyJ Allergy Clin Immunol19971006 Pt 17717749438485

- AkerstedtTPsychological and psychophysiological effects of shift workScand J Work Environ Health199016 Suppl 167732189223

- Smith-CogginsRHowardSKMacDTImproving alertness and performance in emergency department physicians and nurses: The use of planned napsAnn Emerg Med2006485596604 e317052562

- LovatoNLackLFergusonSTremaineRThe effects of a 30-min nap during night shift following a prophylactic sleep in the afternoonSleep Biol Rhythms2009713442

- BlaskDEBrainardGCDauchyRTMelatonin-depleted blood from premenopausal women exposed to light at night stimulates growth of human breast cancer xenografts in nude ratsCancer Res20056523111741118416322268

- KayumovLCasperRFHawaRJBlocking low-wavelength light prevents nocturnal melatonin suppression with no adverse effect on performance during simulated shift workJ Clin Endocrinol Metab20059052755276115713707

- CrowleySJLeeCTsengCYFoggLFEastmanCICombinations of bright light, scheduled dark, sunglasses, and melatonin to facilitate circadian entrainment to night shift workJ Biol Rhythms200318651352314667152

- ZeePCGoldsteinCATreatment of shift work disorder and jet lagCurr Treat Options Neurol201012539641120842597

- JohanssonKHemmingssonEHarlidRLonger term effects of very low energy diet on obstructive sleep apnoea in cohort derived from randomised controlled trial: prospective observational follow-up studyBMJ2011342d301710.1136/bmj.d301721632666

- TuomilehtoHPISeppaJMPartinenMMLifestyle intervention with weight reduction: first-line treatment in mild obstructive sleep apneaAm J Respir Crit Care Med2009179432032719011153

- PayneJKHeldJThorpeJShawHEffect of exercise on biomarkers, fatigue, sleep disturbances, and depressive symptoms in older women with breast cancer receiving hormonal therapyOncol Nurs Forum200835463564218591167

- GaryRLeeSYSPhysical function and quality of life in older women with diastolic heart failure: effects of a progressive walking program on sleep patternsProg Cardiovasc Nurs2007222728017541316

- TworogerSSYasuiYVitielloMVEffects of a yearlong moderate-intensity exercise and a stretching intervention on sleep quality in postmenopausal womenSleep200326783083614655916

- IrwinMROlmsteadRMotivalaSJImproving sleep quality in older adults with moderate sleep complaints: a randomized controlled trial of tai chi chihSleep20083171001100818652095

- LiFFisherKJHarmerPIrbeDTearseRGWeimerCTai chi and self-rated quality of sleep and daytime sleepiness in older adults: A randomized controlled trialJ Am Geriatr Soc200452689290015161452

- DavisCLTkaczJGregoskiMBoyleCALovrekovicGAerobic exercise and snoring in overweight children: A randomized controlled trialObesity (Silver Spring)200614111985199117135615

- WerchCEBianHCarlsonJMBrief integrative multiple behavior intervention effects and mediators for adolescentsJ Behav Med201134131220661637

- CainNGradisarMMoseleyLA motivational school-based intervention for adolescent sleep problemsSleep Med201112324625121292553

- MoseleyLGradisarMEvaluation of a school-based intervention for adolescent sleep problemsSleep200932333434119294953

- PaineSGradisarMA randomised controlled trial of cognitive-behaviour therapy for behavioural insomnia of childhood in school-aged childrenBehav Res Ther2011496–737938821550589

- McAllisterEJDhurandharNVKeithSWTen putative contributors to the obesity epidemicCrit Rev Food Sci Nutr2009491086891319960394

- KuhlESCliffordLMStarkLJObesity in preschoolers: Behavioral correlates and directions for treatmentObesity (Silver Spring)201220132921760634