Abstract

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a systemic inflammatory disorder affecting 1% of the US population. Patients can have extra-articular manifestations of their disease and the lungs are commonly involved. RA can affect any compartment of the respiratory system and high resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of the lung is abnormal in over half of these patients. Interstitial lung disease is a dreaded complication of RA. It is more prevalent in smokers, males, and those with high antibody titers. The pathogenesis is unknown but data suggest an environmental insult in the setting of a genetic predisposition. Smoking may play a role in the pathogenesis of disease through citrullination of protein in the lung leading to the development of autoimmunity. Patients usually present in middle age with cough and dyspnea. Pulmonary function testing most commonly shows reduced diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide and HRCT reveals a combination of reticulation and ground glass abnormalities. The most common pattern on HRCT and histopathology is usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP), with nonspecific interstitial pneumonia seen less frequently. There are no large-scale well-controlled treatment trials. In severe or progressive cases, treatment usually consists of corticosteroids with or without a cytotoxic agent for 6 months or longer. RA interstitial lung disease is progressive; over half of patients show radiographic progression within 2 years. Patients with a UIP pattern on biopsy have a survival similar to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

RA background and review

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a systemic autoimmune disorder characterized by destructive joint disease as well as extra-articular (ExRA) manifestations. The disease is common; it affects 1% of the US adult population and the likelihood of RA increases with age. It is three times more common in women and the prevalence varies by geographic location.Citation1 RA has a heritability of greater than 50% and has been associated with more than 30 specific genetic regions.Citation1,Citation2 Smoking is the primary recognized environmental risk factor and doubles your likelihood of disease.Citation3 RA is characterized by the presence of specific autoantibodies, rheumatoid factor (RF) and antibodies against citrullinated proteins (anti-CCP). Anti-CCP antibodies have a specificity of 95%Citation4 and they can predate the development of clinical evidence of RA; up to 40% of patients have anti-CCP antibodies prior to developing symptomatic joint disease.Citation5

Survival in patients with RA is lower than that seen in the general population, with older age, male gender, and ExRA (including subcutaneous nodules, Sjögren’s syndrome, Keratoconjunctivitis sicca, and pulmonary fibrosis) being risk factors for early mortality.Citation6–Citation8 ExRA are common, with a prevalence approaching 40%.Citation9 Though cardiovascular disease and infection are responsible for the majority of deaths in RA,Citation10–Citation12 10%–20% of deaths appear directly related to pulmonary diseaseCitation13–Citation16 and, in patients with RA and clinically significant pulmonary involvement, over 80% of deaths are due to their lung disease.Citation17 Despite improvements in the management of RA, there have been no substantial improvements in overall mortality.Citation18

Pulmonary manifestations of RA

Any of the anatomic compartments of the lung – airways (bronchiectasis, bronchiolitis), vasculature (pulmonary hypertension, vasculitis), pleura (pleuritis, effusions) or parenchyma (rheumatoid nodules, interstitial lung disease [ILD]) () can be primarily or directly affected by RA. Patients are also at risk for secondary pulmonary complications, with drug toxicities during treatment and opportunistic infections from immunosuppressive therapy being the major concerns.Citation19

Table 1 Pulmonary manifestations of RA

Respiratory symptoms such as breathlessness and cough are common in RA, reported in nearly half of patients, and, when present, correlate with pulmonary physiologic abnormalities.Citation20 In asymptomatic or randomly selected patients, 27%–63% will have pulmonary function testing (PFT) abnormalities.Citation21–Citation24 Patterns include airflow limitation, restriction, or isolated reductions in diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO).Citation21,Citation22,Citation24,Citation25 Despite the large number of patients with measurable physiologic impairment, most abnormalities remain clinically insignificant and asymptomatic patients with PFT abnormalities generally don’t show physiologic progression over 10 years.Citation23 High resolution computed tomography (HRCT) abnormalities are even more common, with 50%–81% of unselected patients showing pathologic changes,Citation21,Citation22,Citation25–Citation30 particularly airways disease,Citation25,Citation28–Citation30 and interstitial disease.Citation21,Citation22,Citation26,Citation27 The likelihood of HRCT abnormalities depends upon the presence of respiratory symptoms; asymptomatic patients will have abnormalities in 48%–68% of HRCTsCitation21,Citation26,Citation27 and symptomatic patients have abnormalities in up to 90%.Citation21,Citation26 HRCT abnormalities are even seen in healthy nonsmokers with early RA (<1 year), with evidence of airways disease most commonly seen.Citation31 HRCT is also more sensitive than pulmonary physiology in detecting pulmonary abnormalities as PFTs are normal in 37% of patients with abnormal HRCT scans.Citation22 Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) is abnormal in 40%–50% of patientsCitation32,Citation33 with an increase in helper T lymphocytes and lower levels of macrophages, B lymphocytes, and suppressor T-cells (leading to an increased CD4/CD8 ratio).Citation34

Patients with RA may develop lung disease from the medications used to treat the joint disease, with reports of pulmonary toxicity from gold,Citation35 penicillamine,Citation36 bucillamine,Citation37 leflunomide,Citation38 methotrexate,Citation39,Citation40 sulfasalazine,Citation41 infliximab,Citation42,Citation43 and tacrolimus.Citation44,Citation45 Methotrexate (MTX) use is associated with an incidence of interstitial pneumonitis of 1%–3%.Citation46,Citation47 There is an associated slight decline in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) in RA patients taking MTXCitation46 but studies looking at PFTs and HRCTs in RA have had mixed results, with some showing declines in function and others showing no clinically significant effect.Citation22,Citation24,Citation48–Citation51 There have also been reports of an increased frequency of MTX pneumonitis after initiation of infliximab therapy.Citation52,Citation53 While rituximab has been linked to rare but severe infections in RA, most of these in the lung,Citation54 the risk of developing infections seems to be comparable to that of other anti-TNF and biologics.Citation55

RA-ILD

History

The first description of ILD in a patient with RA dates back to 1948 when Ellman and Ball described three RA patients with “reticulation” on chest radiographs, two of whom had interstitial fibrosis on postmortem exam.Citation56 The first case of “rheumatoid lung” was reported in 1961, describing the clinical, radiographic, and spirometric characteristics of a single patient.Citation57 Subsequent case reports and case studies sought to draw a connection between clinical RA and ILD but were limited at the time by the sensitivity of the detection methods (plain chest radiographs) and debate on the relationship between RA and ILD.Citation58,Citation59 When single breath diffusion studies were combined with chest radiographs, the reported incidence of disease increased (up to 40% in one study).Citation60 In 1972, Popper and colleagues further solidified the relationship when they prospectively evaluated RA patients with chest radiographs and physiology and found abnormalities in 33%.Citation61 Since then, numerous studies have found a strong association between RA and ILD.Citation33,Citation62–Citation67

Risk factors for RA-ILD

The lifetime risk for developing ILD in the setting of RA is approximately 8% compared to 1% in the general population.Citation68 Multiple risk factors for its development have been identified (). Smoking is one of the strongest risk factorsCitation51,Citation69–Citation71 and, in a cohort of 336 patients with RA-ILD, smoking was the most consistent independent predictor of radiographic and physiologic abnormalities suggestive of ILD.Citation70 Male gender has been associated with ILDCitation33,Citation70,Citation72–Citation74 but this relationship isn’t seen in all studies.Citation22,Citation65,Citation75 Other documented risk factors include high-titer RF,Citation22,Citation65,Citation76 high-titer anti-CCP,Citation77 advanced age,Citation22,Citation65 genetic background,Citation78,Citation79 and the presence of clinically severe RA.Citation22,Citation70,Citation80

Table 2 Risk factors for ILD in RA

Prevalence

The literature reports a wide variance in the prevalence of ILD in RA. The prevalence depends on clinical phenotype (eg, the presence or absence of respiratory symptoms), gender (more men would likely favor more ILD), duration of disease, clinical severity of RA, percentage of smokers, autoantibody profile, history of treatment, and the methods of diagnosis. Early studies utilizing chest radiographs found a prevalence of ILD of 1%–5%.Citation57,Citation69,Citation81 Subsequent studies screened patients irrespective of symptoms and have found a prevalence ranging from 19%–58%.Citation33,Citation65,Citation70 In patients with a documented lack of symptoms of lung disease, the prevalence is lower at 44%.Citation33 Lung biopsies performed on hospitalized patients with RA found interstitial changes in 80%, with half of these patients having no symptoms.Citation63

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of RA-ILD is unknown. The available data points to the presence of an environmental insult in the setting of a genetic predisposition. Though the data is limited HLA-B54, HLA-DQB 1*0601, HLA-B40, and HLA-DR4 as well as the site that encodes for the α1-protease inhibitor have all been linked to lung disease in RA.Citation78,Citation79,Citation82–Citation84 With this genetic predisposition, there is evidence of immune dysregulation with alterations in both T and B cells. Patients with RA-ILD have higher levels of CD4+ cells and CD54+ T cells in their lungs when compared to patients with one of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIPs), suggesting a maladaptive immune response and chronic T cell activation.Citation85,Citation86 B-cells are also involved as patients with RA have higher levels of CD20 positive B-cells in peribronchiolar lymphoid aggregates.Citation87 Histopathologically, more germinal centers and lymphoplasmocytic cellular inflammation and fewer fibroblast foci are seen when compared to the IIPs.Citation88 The cytokine milieu is also different in these patients. Patients with RA and established fibrosis have lower levels of IFN-γ and TGF-β2 than those with no ILD or mild ILD.Citation51 In addition, patients with RA-ILD have higher levels of TNF-α and IL-6 production by macrophages when compared to healthy controlsCitation89 and PDGF levels are higher in BAL fluid.Citation51 Finally, patients with RA-ILD have increased levels of high proliferative potential colony-forming cells in their peripheral blood compared to those without ILD and it is felt that these are possible progenitor cells for alveolar macrophages.Citation90

The role of smoking

Recent attention has been focused on the lungs as a possible site for initiation of the immune dysregulation that leads to clinical RA. Smoking is an established risk factor for the development of RACitation91 as well as the development of RA-ILD.Citation51,Citation69–Citation71 There has been recent interest in the relationship between citrullinated protein, HLA-DR shared epitopes, smoking, and the development of RA. HLA-DR shared epitopes are the major genetic risk factors for the development of RACitation92 and it was found that smokers with HLA-DR shared epitopes have up to a 21-fold increase in the risk of developing anti-CCP antibody positive RA.Citation93 Smokers have citrullinated proteins in their lung lavage fluidCitation94 and citrullinated proteins are seen in the synovium of patients with RACitation95 as well as rheumatoid nodules and the parenchyma of patients with RA-associated ILD.Citation96 Smoking increases your likelihood of having anti-CCP antibodies at the onset of RA in a dose-dependent fashionCitation97 and there is an increased prevalence of lung disease (predominately ILD) in patients with high-titer anti-CCP antibodies.Citation72 This data suggests that, in certain patients with the appropriate genetic predisposition, the immune dysregulation that is seen in patients with RA could originate in the lungs and be related to tobacco smoke-induced citrullination of proteins, leading to the production of autoimmunity and the subsequent development of clinical arthritis. This does not explain all cases, as the development of RA-ILD is not dependent on a history of tobacco use.Citation98

Clinical features

Patients usually present in their late 50s to 60sCitation99–Citation101 after an average of 10–12 years with RA.Citation99,Citation101 Among all comers with ILD, there is an even split between men and womenCitation100,Citation101 though there seem to be gender differences among the various histopathologic subtypes of ILD (with men more commonly having usual interstitial pneumonia [UIP]Citation17,Citation101 and women more commonly having nonspecific interstitial pneumonia [NSIP]Citation102). In two-thirds of patients, a confirmed diagnosis of RA precedes the diagnosis of ILD, though ILD can be occasionally precede the joint disease (up to 7 years in one study).Citation101 Most patients with ILD will have symptoms such as cough or dyspneaCitation103 though preclinical disease is commonly found when looked for by chest imaging or physiology.Citation51 Crackles are commonly found on exam and are more frequent than in those RA patients without ILD.Citation51,Citation65,Citation104 Finger clubbing is seen less commonly than in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).Citation66

Pulmonary function testing

Pulmonary physiologic screening in early RA (<2 years duration) irrespective of symptoms finds PFT abnormalities consistent with ILD in 22% of patients.Citation33 A reduction in DLCO is the most common finding,Citation33,Citation65 may be the earliest physiologic change (those with RA and clinically silent ILD can have isolated reductions in DLCOCitation33,Citation51), and correlates with the extent of reticulation on HRCT.Citation75,Citation99 A reduction is seen in more than 50% of all patients screened and in 82% of those with documented ILD.Citation65,Citation105 It has also been found to be a highly specific predictor of disease progression in patients with UIP and RA.Citation106 PFTs likely change later than HRCT in the course of disease as patients with preclinical disease can have an abnormal HRCT in the setting of normal PFTs.Citation65

Chest imaging

In patients with RA-ILD, chest X-rays frequently show reticular, reticulonodular or honeycomb changes in the lung bases.Citation107 The chest X-ray, however, is insensitive as greater than 50% of patients who have a normal plain chest radiograph will have abnormalities on their HRCT.Citation33,Citation65 Therefore, HRCT has replaced plain chest X-rays in the initial evaluation of the RA patient with potential lung disease. The incidence of ILD on HRCT depends on the clinical phenotype of the population evaluated. A study screening nonsmokers without respiratory symptoms found evidence of ILD on HRCT in 33%.Citation51 Early RA (<2 years duration) patients have evidence of ILD on HRCT in a third of cases, though the extent of disease is mild.Citation33 In both early and longstanding RA, HRCT changes can precede changes in PFTs.Citation31,Citation108 In looking at patients with clinically suspected ILD (symptoms, impaired lung function, or abnormal CXR), 92% have HRCT findings consistent with ILD.Citation99

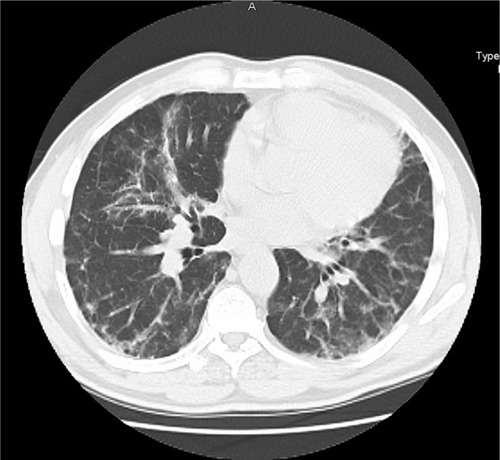

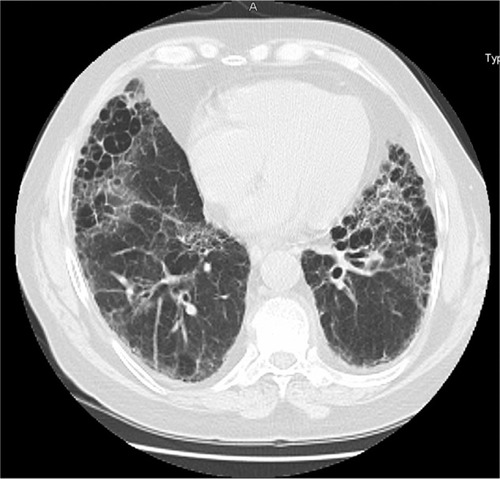

The most common abnormal findings are ground glass opacities (GGOs) and reticulation, seen in over 90% of patients,Citation75 with reticulation seen in 65%–79% of HRCTsCitation99,Citation109 and seen in isolation in long-standing disease.Citation99 GGOs are seen in 27% of patients, rarely seen in isolation (reported as the only HRCT abnormality in 0/49 HRCTs in one study), and are more common in patients with a shorter duration of disease.Citation99 Less common findings include honeycombing, traction bronchiectasis, nodules, centrilobular branching lines, and consolidation.Citation75,Citation109 Patterns of involvement on HRCT correspond to patterns identified in the IIPs ( and ). In patients with RA referred to an interstitial lung disease center, patterns of ILD on HRCT include UIP (40%), NSIP (30%), bronchiolitis (17%), and organizing pneumonia (8%).Citation75 Other studies have found similar percentages of UIP and NSIP.Citation110 Occasionally, patients will have more than HRCT pattern.Citation75

Figure 1 High resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of RA-ILD with an NSIP pattern. An HRCT of a patient with RA showing peripheral reticulation and ground glass abnormalities with no notable honeycombing.

Figure 2 High resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of RA-ILD with a UIP pattern. An HRCT of a patient with RA showing reticulation and significant honeycombing in a basilar and peripheral distribution with an absence of significant ground glass abnormality.

HRCT findings are well-correlated with underlying histopathology.Citation75,Citation109 Reticulation and honeycomb change are associated more frequently with pathologic UIP.Citation75 GGOs can be found in both UIP and NSIP but are more pronounced and diffuse in the latter.Citation75 Centrilobular branching is seen with bronchiolitis obliterans and consolidation correlates with organizing pneumonia.Citation109 There are also associations between HRCT findings and physiology. The degree of parenchymal involvement in RA-ILD is correlated with decreases in FEV1, FVC, and DLCO.Citation99 Finally, a recent study found that survival is linked to HRCT pattern as patients with a “definite UIP” pattern had a survival that was significantly worse than those with an indeterminate pattern or a pattern suggestive of NSIP.Citation100

BAL

Patients with clinically significant RA-ILD have an increase in the total cellular concentration,Citation111 increases in neutrophils, lymphocytes, and eosinophils,Citation32,Citation33 and a decreased CD4/CD8 ratioCitation32,Citation111 on bronchoalveolar lavage compared to those without ILD. Abnormal BAL findings can also be seen in patients with RA and subclinical ILDCitation112 and elevated lymphocyte counts in these patients may help to distinguish them from those with normal physiology and chest radiographs.Citation113 BAL findings have only a moderate correlation to the lesions found on HRCT, with a higher number of neutrophils found in patients with GGOs.Citation99

Histopathology

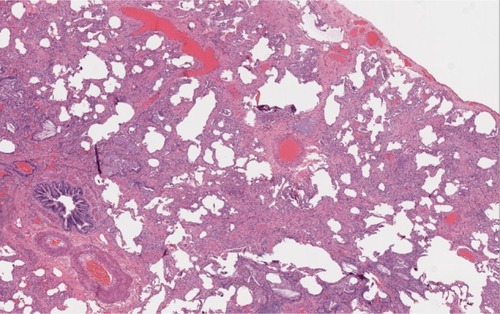

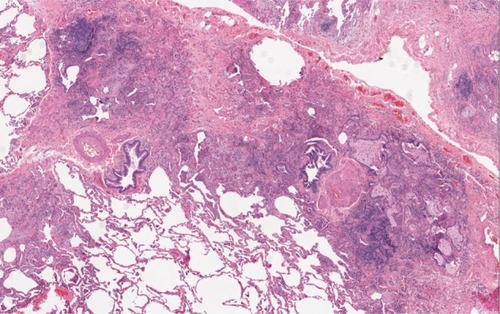

Studies of comparative histopathology in RA-ILD patients are complicated by a significant selection bias, as more severely impaired patients and those with unclear HRCT patterns tend to get surgical lung biopsies. Though NSIP is the most common histopathologic pattern seen in patients with other collagen-vascular associated ILDs, in patients with RA-ILD, UIP is more common than NSIP (60% vs 35%)Citation101,Citation114 ( and ). Patients with UIP are more likely to be male and current or former smokers when compared to NSIP,Citation17,Citation101 though the relationship between smoking and RA-ILD associated UIP is not seen in all studies.Citation100 In RA-ILD associated UIP, fewer fibroblast foci, more inflammation, and a higher number of germinal centers are seen when compared to idiopathic UIP.Citation88 Patients with RA-ILD will also have increased CD4+ T-cell infiltrates when compared to the IIPs.Citation85 They often have concomitant lymphocytic bronchiolitisCitation115 and well-developed bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue.Citation116 Occasionally, biopsy specimens in these patients will have more than one histopathologic pattern.Citation117 Other patterns in RA-ILD have been reported with lesser frequencies, including organizing pneumonia, diffuse alveolar damage, lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia, and desquamative interstitial pneumonia.

Figure 3 Histopathology in a patient with RA-ILD associated NSIP. A surgical biopsy specimen in a patient with RA showing cellular interstitial infiltrates and fibrosis in a temporally uniform distribution.

Figure 4 Histopathology in a patient with RA-ILD associated UIP. A surgical biopsy specimen in a patient with RA showing patchy interstitial fibrosis that starts in the peripheral acinar regions and is in close proximity to unaffected lung tissue.

Biomarkers

Biologic fluid-based biomarkers have been looked at in BAL fluid. Patients with early asymptomatic RA-ILD have higher levels of the platelet-derived growth factor-AB and BB in BAL fluid and those with established UIP on biopsy have lower levels of IFN-γ and TGF-β2.Citation51 Patients with progressive disease have higher levels of IFN-γ and TGF-β1.Citation51 Levels of KL-6 are higher in patients with RA-ILD associated UIPCitation118 as well as other subtypes of RA-ILD.Citation17

Treatment

Rigorous treatment trials in patients with RA-ILD are lacking, and to date there has been no large-scale well-controlled treatment trial. There are limited reports of treatment with methotrexate,Citation119 azathioprine,Citation120 cyclosporine,Citation121 mycophenolate mofetil,Citation122 and TNF-α inhibitors.123124 Current treatment regimens are variable and usually include corticosteroids with or without a cytotoxic agent such as azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil. Treatment duration varies but is usually 6 months or longer.

There have been concerns about the anti-tumor necrosis factor agents and their possible association with the progression of ILD in patients with RA. There have been case reports of exacerbations of existing ILD or new interstitial pneumonitis in patients with RA taking infliximab.Citation43,Citation125,Citation126 Etanercept has been linked to granulomatous lung disease and exacerbation of pre-existing lung disease in patients with RA.Citation127,Citation128 In spite of these reports, a recent review of 367 patients with RA-ILD treated with either anti-TNF agents or traditional RA treatments found no difference in mortality.Citation129

Outcome

RA-ILD is progressive in the majority of patients; up to 57% of patients with early asymptomatic RA-ILD had progression on HRCT during a mean follow-up of 1.5 years and 60% of patients with established RA-ILD and a UIP histopathologic pattern had progression on HRCT during this time frame.Citation51 Another study found that 34% of patients with RA and fibrosing alveolitis progressed radiographically over 24 months of follow-up.Citation106 Reduced DLCO has been associated with progression of disease in those patients with a UIP histopathologic pattern, with a DLCO < 54% predicted demonstrating a 80% sensitivity and 93% specificity in predicting progressive disease.Citation106 The use of MTX has also been suggested as a risk factor for progression.Citation51 In some RA patients, pulmonary fibrosis is rapidly progressive (25% in one series)Citation130 and patients with pulmonary fibrosis that leads to hospitalization have a median survival of 3.5 years.Citation131

Yousem and colleagues were one of the first to report that among RA patients with ILD, those with a histologic pattern of UIP in surgical lung biopsy specimens had the worst prognosis.Citation117 Results from subsequent studies have confirmed their findings.Citation101,Citation131 A recent study found 5-year survival rates of 36% in patients with UIP and 94% in NSIPCitation17 (with other studies confirming the favorable outcome in NSIP and reporting no fatal cases of RA-ILD associated NSIPCitation17,Citation101). The prognosis of RA-ILD compared to IPF has long been debated with some studies finding similar outcomesCitation132,Citation133 and others suggesting that RA-ILD patients have a longer survival than IPF.Citation104,Citation134 Recent studies that have looked at RA patients with UIP on either HRCT or pathology have found a survival similar to that in IPF.Citation100,Citation114 In patients with RA-ILD with a UIP histopathologic pattern, the presence of traction bronchiectasis and honeycomb fibrosis, male gender, and a reduced DLCO are associated with a worse survival rate.Citation100

Workup and evaluation

Rheumatologists should have a high index of suspicion for lung disease in all patients with RA. Symptoms such as cough and/or breathlessness and physical exam findings such as crackles significantly increase the likelihood of ILD, and other patient characteristics (such as active smoking, male gender, and CCP positivity) should lower the threshold for evaluation. Though patients with limited mobility from their joint disease are at risk of presenting with more severe pulmonary involvement, screening for pulmonary involvement in the asymptomatic patient should occur with a clear plan in mind for dealing with the findings. There is no data to guide the treatment of preclinical disease and is therefore of uncertain benefit. In patients with suggestive signs or symptoms, pulmonary physiology can be useful; however, patients with early and mild disease may have normal PFTs and more sensitive testing for ILD requires an HRCT. Defining the underlying subtype of ILD by histopathologic pattern (NSIP, UIP) is helpful to stratify patients’ risk for disease progression and early mortality; however, HRCT patterns are highly predictive of the underlying histopathology and lung biopsy is reserved for cases with atypical clinical or chest imaging features.

Patients with ILD should be referred to a pulmonologist. Smoking patients should be encouraged to quit and MTX should generally be avoided in these patients. Adequate control of a patient’s joint symptoms should not be seen as a surrogate for control of the lung disease and does not obviate the need for close lung-specific follow-up for patients with documented lung disease.

It is our practice to treat patients with clinically significant symptoms, or physiologically or radiographically advanced disease on presentation or with evidence of symptomatic, physiologic, or radiographic progression. With a paucity of published data to guide our decisions, treatment at our tertiary referral center is based on clinical experience. Treatment incorporates the clinical importance of controlling joint symptoms and generally consists of a combination of a corticosteroid and a cytotoxic agent such as azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil. Failure of response to the initial agent is often followed by a trial with the alternative cytotoxic agent. We have treated patients with life-threatening disease with cyclophosphamide, though with mixed results. Anecdotal responses as measured by stability of disease have been noted with rituximab. As with all treatments, side-effects must be thoroughly discussed with the patients and clinicians should follow the accepted monitoring schedule. A response to therapy generally requires at least 3–6 months of treatment with responses monitored by indices of symptoms, oxygenation, pulmonary physiology, and chest imaging with HRCTs. A response is defined as an improvement in one or more of these indices. Stabilization or a reduced rate of decline may also indicate a response. Other treatment such as comprehensive rehabilitation and maintenance of normoxia as well as a regular search for comorbidities such as silent reflux and obstructive sleep apnea should be considered.

Summary

Lung disease is common in RA and can involve all compartments of the lung. Up to 80% of HRCTs of the chest are abnormal, showing predominately airways disease and ILD. ILD is more common in men, advanced age, and those with high-titer CCP. Smoking appears to be involved as it citrullinates proteins in the lung, increases the likelihood of having anti-CCP antibodies, and increases the risk of both RA and its associated ILD. Patients present in their 50s and 60s with symptoms of cough and breathlessness. Infrequently, ILD can precede the development of joint disease. Pulmonary physiologic findings are variable and can show restriction, obstruction, or a reduction in the DLCO. HRCT reveals patterns similar to those seen in the IIPs. Pathology correlates well with findings on HRCT and most commonly reveals UIP (with one-third of patients having an NSIP pattern). UIP in RA differs from the idiopathic form with more germinal centers and fewer fibroblastic foci. There are no large-scale treatment trials for RA-ILD and the existing data comes from case reports and series with varying clinical phenotypes. Patient with UIP have the worst prognosis (5-year survival rate of 36%) and a survival that may be similar to those with IPF. Rheumatologists should have a high index of suspicion for lung disease in patients with RA and refer those with abnormal testing to a pulmonologist.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- ScottDLWolfeFHuizingaTWRheumatoid arthritisLancet201037697461094110820870100

- van der WoudeDHouwing-DuistermaatJJToesREQuantitative heritability of anti-citrullinated protein antibody-positive and anti-citrullinated protein antibody-negative rheumatoid arthritisArthritis Rheum200960491692319333951

- CarlensCHergensMPGrunewaldJSmoking, use of moist snuff, and risk of chronic inflammatory diseasesAm J Respir Crit Care Med2010181111217122220203245

- AvouacJGossecLDougadosMDiagnostic and predictive value of anti-cyclic citrullinated protein antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature reviewAnn Rheum Dis200665784585116606649

- NielenMMvan SchaardenburgDReesinkHWSpecific autoantibodies precede the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis: a study of serial measurements in blood donorsArthritis Rheum200450238038614872479

- RadovitsBJFransenJAl ShammaSEijsboutsAMvan RielPLLaanRFExcess mortality emerges after 10 years in an inception cohort of early rheumatoid arthritisArthritis Care Res (Hoboken)201062336237020391482

- GabrielSECrowsonCSKremersHMSurvival in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based analysis of trends over 40 yearsArthritis Rheum2003481545812528103

- TuressonCO’FallonWMCrowsonCSGabrielSEMattesonELOccurrence of extraarticular disease manifestations is associated with excess mortality in a community based cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritisJ Rheumatol2002291626711824973

- TuressonCO’FallonWMCrowsonCSGabrielSEMattesonELExtra-articular disease manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis: incidence trends and risk factors over 46 yearsAnn Rheum Dis200362872272712860726

- Maradit-KremersHNicolaPJCrowsonCSBallmanKVGabrielSECardiovascular death in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based studyArthritis Rheum200552372273215751097

- KootaKIsomakiHMutruODeath rate and causes of death in RA patients during a period of five yearsScand J Rheumatol197764241244607393

- ToyoshimaHKusabaTYamaguchiMCause of death in autopsied RA patientsRyumachi19933332092148346462

- MinaurNJJacobyRKCoshJATaylorGRaskerJJOutcome after 40 years with rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective study of function, disease activity, and mortalityJ Rheumatol Suppl2004693815053445

- SihvonenSKorpelaMLaippalaPMustonenJPasternackADeath rates and causes of death in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based studyScand J Rheumatol200433422122715370716

- SuzukiAOhosoneYObanaMCause of death in 81 autopsied patients with rheumatoid arthritisJ Rheumatol199421133368151583

- YoungAKoduriGBatleyMMortality in rheumatoid arthritis. Increased in the early course of disease, in ischaemic heart disease and in pulmonary fibrosisRheumatology200746235035716908509

- TsuchiyaYTakayanagiNSugiuraHLung diseases directly associated with rheumatoid arthritis and their relationship to outcomeEuro Respir J201137614111417

- MyasoedovaEDavisJM3rdCrowsonCSGabrielSEEpidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis: rheumatoid arthritis and mortalityCurr Rheumatol Rep201012537938520645137

- BrownKKRheumatoid lung diseaseProc Am Thorac Soc20074544344817684286

- PappasDAGilesJTConnorsGLechtzinNBathonJMDanoffSKRespiratory symptoms and disease characteristics as predictors of pulmonary function abnormalities in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: an observational cohort studyArthritis Res Ther2010123R10420507627

- KanatFLevendogluFTekeTRadiological and functional assessment of pulmonary involvement in the rheumatoid arthritis patientsRheumatol Int200727545946617028857

- BilgiciAUlusoyHKuruOCelenkCUnsalMDanaciMPulmonary involvement in rheumatoid arthritisRheumatol Int200525642943516133582

- FuldJPJohnsonMKCottonMMA longitudinal study of lung function in non-smoking patients with rheumatoid arthritisChest200312441224123114555550

- AvnonLSManzurFBolotinAPulmonary functions testing in patients with rheumatoid arthritisIsr Med Assoc J2009112838719432035

- CortetBPerezTRouxNPulmonary function tests and high resolution computed tomography of the lungs in patients with rheumatoid arthritisAnn Rheum Dis199756105966009389220

- ZrourSHTouziMBejiaICorrelations between high-resolution computed tomography of the chest and clinical function in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Prospective study in 75 patientsJoint Bone Spine2005721414715681247

- DemirRBodurHTokogluFOlcayIUcanHBormanPHigh resolution computed tomography of the lungs in patients with rheumatoid arthritisRheumatol Int1999191–2192210651076

- HassanWUKeaneyNPHollandCDKellyCAHigh resolution computed tomography of the lung in lifelong non-smoking patients with rheumatoid arthritisAnn Rheum Dis19955443083107763110

- PerezTRemy-JardinMCortetBAirways involvement in rheumatoid arthritis: clinical, functional, and HRCT findingsAm J Respir Crit Care Med19981575 Pt 1165816659603152

- TerasakiHFujimotoKHayabuchiNOgohYFukudaTMullerNLRespiratory symptoms in rheumatoid arthritis: relation between high resolution CT findings and functional impairmentRadiat Med200422317918515287534

- MetafratziZMGeorgiadisANIoannidouCVPulmonary involvement in patients with early rheumatoid arthritisScand J Rheumatol200736533834417963162

- GarciaJGParhamiNKillamDGarciaPLKeoghBABronchoalveolar lavage fluid evaluation in rheumatoid arthritisAm Rev Respir Disease198613334504543485395

- GabbayETaralaRWillRInterstitial lung disease in recent onset rheumatoid arthritisAm J Respir Crit Care Med19971562 Pt 15285359279235

- KolarzGScherakOPoppWBronchoalveolar lavage in rheumatoid arthritisBr J Rheumatol19933275565618339125

- EvansRBEttensohnDBFawaz-EstrupFLallyEVKaplanSRGold lung: recent developments in pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapySem Arthritis Rheum1987163196205

- ShettarSPChattopadhyayCWolstenholmeRJSwinsonDRDiffuse alveolitis on a small dose of penicillamineBr J Rheumatol19842332202246743969

- NegishiMKagaSKasamaTLung injury associated with bucillamine therapyRyumachi1992322135139 Japanese1595005

- InokumaSLeflunomide-induced interstitial pneumonitis might be a representative of disease-modifying antirheumatic drug-induced lung injuryExpert Opin Drug Saf201110460361121410426

- KremerJMAlarconGSWeinblattMEClinical, laboratory, radiographic, and histopathologic features of methotrexate-associated lung injury in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a multicenter study with literature reviewArthritis Rheum19974010182918379336418

- CannonGWMethotrexate pulmonary toxicityRheum Dis Clin North Am19972349179379361161

- HamadehMAAtkinsonJSmithLJSulfasalazine-induced pulmonary diseaseChest19921014103310371348220

- ChatterjeeSSevere interstitial pneumonitis associated with infliximab therapyScand J Rheumatol200433427627715370726

- OstorAJChilversERSomervilleMFPulmonary complications of infliximab therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritisJ Rheumatol200633362262816511933

- KoikeRTanakaMKomanoYTacrolimus-induced pulmonary injury in rheumatoid arthritis patientsPulm Pharmacol Ther201124440140621300166

- MiwaYIsozakiTWakabayashiKTacrolimus-induced lung injury in a rheumatoid arthritis patient with interstitial pneumonitisMod Rheumatol200818220821118306979

- CottinVTebibJMassonnetBSouquetPJBernardJPPulmonary function in patients receiving long-term low-dose methotrexateChest199610949339388635373

- KinderAJHassellABBrandJBrownfieldAGroveMShadforthMFThe treatment of inflammatory arthritis with methotrexate in clinical practice: treatment duration and incidence of adverse drug reactionsRheumatology2005441616615611303

- KhadadahMEJayakrishnanBAl-GorairSEffect of methotrexate on pulmonary function in patients with rheumatoid arthritis – a prospective studyRheumatol Int200222520420712215867

- DawsonJKGrahamDRDesmondJFewinsHELynchMPInvestigation of the chronic pulmonary effects of low-dose oral methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective study incorporating HRCT scanning and pulmonary function testsRheumatology (Oxford)200241326226711934961

- GaffoALAlarconGSMethotrexate is not associated with progression of interstitial lung disease in rheumatoid arthritisArch Intern Med2008168171927192818809822

- GochuicoBRAvilaNAChowCKProgressive preclinical interstitial lung disease in rheumatoid arthritisArch Intern Med2008168215916618227362

- CourtneyPAAlderdiceJWhiteheadEMComment on methotrexate pneumonitis after initiation of infliximab therapy for rheumatoid arthritisArthritis Rheum2003494617 author reply 617–61812910574

- KramerNChuzhinYKaufmanLDRitterJMRosensteinEDMethotrexate pneumonitis after initiation of infliximab therapy for rheumatoid arthritisArthritis Rheum200247667067112522843

- GottenbergJERavaudPBardinTRisk factors for severe infections in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with rituximab in the autoimmunity and rituximab registryArthritis Rheum20106292625263220506353

- Hernandez-CruzBGarcia-AriasMAriza ArizaRMartin MolaERituximab in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of efficacy and safetyReumatol Clin201175314322 Spanish21925447

- EllmanPBallRERheumatoid disease with joint and pulmonary manifestationsBr Med J19482458381682018890308

- CudkowiczLMadoffIMAbelmannWHRheumatoid lung disease. A case report which includes respiratory function studies and a lung biopsyBr J Dis Chest196155354013718774

- AronoffABywatersEGFearnleyGRLung lesions in rheumatoid arthritisBr Med J19552493322823214389733

- TalbottJACalkinsEPulmonary involvement in rheumatoid arthritisJAMA196418991191314172906

- FrankSTWegJGHarkleroadLEFitchRFPulmonary dysfunction in rheumatoid diseaseChest197363127344684107

- PopperMSBogdonoffMLHughesRLInterstitial rheumatoid lung disease. A reassessment and review of the literatureChest19726232432505066501

- PoppWRauscherHRitschkaLPrediction of interstitial lung involvement in rheumatoid arthritis. The value of clinical data, chest roentgenogram, lung function, and serologic parametersChest199210223913941643920

- Cervantes-PerezPToro-PerezAHRodriguez-JuradoPPulmonary involvement in rheumatoid arthritisJAMA198024317171517197365934

- FujiiMAdachiSShimizuTHirotaSSakoMKonoMInterstitial lung disease in rheumatoid arthritis: assessment with high-resolution computed tomographyJ Thorac Imaging19938154628418318

- DawsonJKFewinsHEDesmondJLynchMPGrahamDRFibrosing alveolitis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis as assessed by high resolution computed tomography, chest radiography, and pulmonary function testsThorax200156862262711462065

- RajasekaranBAShovlinDLordPKellyCAInterstitial lung disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a comparison with cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitisRheumatology (Oxford)20014091022102511561113

- HortonMRRheumatoid arthritis associated interstitial lung diseaseCrit Rev Comput Tomogr2004455–642944015747578

- BongartzTNanniniCMedina-VelasquezYFIncidence and mortality of interstitial lung disease in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based studyArthritis Rheum20106261583159120155830

- JurikAGDavidsenDGraudalHPrevalence of pulmonary involvement in rheumatoid arthritis and its relationship to some characteristics of the patients. A radiological and clinical studyScand J Rheumatol19821142172247178857

- SaagKGKolluriSKoehnkeRKRheumatoid arthritis lung disease. Determinants of radiographic and physiologic abnormalitiesArthritis Rheum19963910171117198843862

- BanksJBanksCCheongBAn epidemiological and clinical investigation of pulmonary function and respiratory symptoms in patients with rheumatoid arthritisQ J Med199285307–3087958061484943

- AubartFCrestaniBNicaise-RolandPHigh levels of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide autoantibodies are associated with co-occurrence of pulmonary diseases with rheumatoid arthritisJ Rheumatol201138697998221362759

- AnayaJMDiethelmLOrtizLAPulmonary involvement in rheumatoid arthritisSemin Arthritis Rheum19952442422547740304

- ShidaraKHoshiDInoueEIncidence of and risk factors for interstitial pneumonia in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in a large Japanese observational cohort, IORRAMod Rheumatol201020328028620217173

- TanakaNKimJSNewellJDRheumatoid arthritis-related lung diseases: CT findingsRadiology20042321819115166329

- SakaidaHIgG rheumatoid factor in rheumatoid arthritis with interstitial lung diseaseRyumachi1995354671677 Japanese7482064

- AlexiouIGermenisAKoutroumpasAKontogianniATheodoridouKSakkasLIAnti-cyclic citrullinated peptide-2 (CCP2) autoantibodies and extra-articular manifestations in Greek patients with rheumatoid arthritisClin Rheumatol200827451151318172572

- ScottTEWiseRAHochbergMCWigleyFMHLA-DR4 and pulmonary dysfunction in rheumatoid arthritisAm J Med19878247657713494398

- CharlesPJSweatmanMCMarkwickJRMainiRNHLA-B40: a marker for susceptibility to lung disease in rheumatoid arthritisDis Markers199192971011782749

- TanoueLTPulmonary manifestations of rheumatoid arthritisClin Chest Med1998194667685 viii9917959

- HylandRHGordonDABroderIA systematic controlled study of pulmonary abnormalities in rheumatoid arthritisJ Rheumatol19831033954056887163

- SugiyamaYOhnoSKanoSMaedaHKitamuraSDiffuse panbronchiolitis and rheumatoid arthritis: a possible correlation with HLA-B54Intern Med199433106126147827377

- HillarbyMCMcMahonMJGrennanDMHLA associations in subjects with rheumatoid arthritis and bronchiectasis but not with other pulmonary complications of rheumatoid diseaseBr J Rheumatol19933297947978369890

- MichalskiJPMcCombsCCScopelitisEBiundoJJJrMedsgerTAJrAlpha 1-antitrypsin phenotypes, including M subtypes, in pulmonary disease associated with rheumatoid arthritis and systemic sclerosisArthritis Rheum19862955865913487321

- TuressonCMattesonELColbyTVIncreased CD4+ T cell infiltrates in rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial pneumonitis compared with idiopathic interstitial pneumonitisArthritis Rheum2005521737915641082

- MichelJJTuressonCLemsterBCD56-expressing T cells that have features of senescence are expanded in rheumatoid arthritisArthritis Rheum2007561435717195207

- AtkinsSRTuressonCMyersJLMorphologic and quantitative assessment of CD20+ B cell infiltrates in rheumatoid arthritis-associated nonspecific interstitial pneumonia and usual interstitial pneumoniaArthritis Rheum200654263564116447242

- SongJWDoKHKimMYJangSJColbyTVKimDSPathologic and radiologic differences between idiopathic and collagen vascular disease-related usual interstitial pneumoniaChest20091361233019255290

- AncocheaJGironRMLopez-BotetMProduction of tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-6 by alveolar macrophages from patients with rheumatoid arthritis and interstitial pulmonary diseaseArch Bronconeumol1997337335340 Spanish9410434

- HorieSNakadaKMinotaSKanoSHigh proliferative potential colony-forming cells (HPP-CFCs) in the peripheral blood of rheumatoid arthritis patients with interstitial lung diseaseScand J Rheumatol200332527327614690139

- AlbanoSASantana-SahagunEWeismanMHCigarette smoking and rheumatoid arthritisSem Arthritis Rheum2001313146159

- JawaheerDGregersenPKRheumatoid arthritis. The genetic componentsRheum Dis Clin North Am2002281115 v11840692

- KlareskogLStoltPLundbergKA new model for an etiology of rheumatoid arthritis: smoking may trigger HLA-DR (shared epitope)-restricted immune reactions to autoantigens modified by citrullinationArthritis Rheum2006541384616385494

- MakrygiannakisDHermanssonMUlfgrenAKSmoking increases peptidylarginine deiminase 2 enzyme expression in human lungs and increases citrullination in BAL cellsAnn Rheum Dis200867101488149218413445

- De RyckeLNicholasAPCantaertTSynovial intracellular citrullinated proteins colocalizing with peptidyl arginine deiminase as pathophysiologically relevant antigenic determinants of rheumatoid arthritis-specific humoral autoimmunityArthritis Rheum20055282323233016052592

- BongartzTCantaertTAtkinsSRCitrullination in extra-articular manifestations of rheumatoid arthritisRheumatology (Oxford)2007461707516782731

- StoltPBengtssonCNordmarkBQuantification of the influence of cigarette smoking on rheumatoid arthritis: results from a population based case-control study, using incident casesAnn Rheum Dis200362983584112922955

- Ayhan-ArdicFFOkenOYorganciogluZRUstunNGokharmanFDPulmonary involvement in lifelong non-smoking patients with rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis without respiratory symptomsClin Rheumatol200625221321816091838

- BiedererJSchnabelAMuhleCGrossWLHellerMReuterMCorrelation between HRCT findings, pulmonary function tests and bronchoalveolar lavage cytology in interstitial lung disease associated with rheumatoid arthritisEur Radiol200414227228014557895

- KimEJElickerBMMaldonadoFUsual interstitial pneumonia in rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung diseaseEur Respir J20103561322132819996193

- LeeHKKimDSYooBHistopathologic pattern and clinical features of rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung diseaseChest200512762019202715947315

- LuqmaniRHennellSEstrachCBritish Society for Rheumatology and British Health Professionals in Rheumatology guideline for the management of rheumatoid arthritis (after the first 2 years)Rheumatology200948443643919174570

- RoschmannRARothenbergRJPulmonary fibrosis in rheumatoid arthritis: a review of clinical features and therapySemin Arthritis Rheum19871631741853547656

- RajasekaranAShovlinDSaravananVLordPKellyCInterstitial lung disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: comparison with cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis over 5 yearsJ Rheumatol20063371250125316758510

- ProvenzanoGAsymptomatic pulmonary involvement in RAThorax200257218718811828057

- DawsonJKFewinsHEDesmondJLynchMPGrahamDRPredictors of progression of HRCT diagnosed fibrosing alveolitis in patients with rheumatoid arthritisAnn Rheum Dis200261651752112006324

- ShannonTMGaleMENoncardiac manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis in the thoraxJ Thorac Imaging19927219291578523

- McDonaghJGreavesMWrightARHeycockCOwenJPKellyCHigh resolution computed tomography of the lungs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and interstitial lung diseaseBr J Rheumatol19943321181228162474

- AkiraMSakataniMHaraHThin-section CT findings in rheumatoid arthritis-associated lung disease: CT patterns and their coursesJ Comput Assist Tomogr199923694194810589572

- KimEJCollardHRKingTEJrRheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease: the relevance of histopathologic and radiographic patternChest200913651397140519892679

- OkudaYTakasugiKKurataNTakaharaJBronchoalveolar lavage fluid analysis in rheumatoid arthritisRyumachi1993334302309 Japanese8235911

- GilliganDMO’ConnorCMWardKMoloneyDBresnihanBFitzGeraldMXBronchoalveolar lavage in patients with mild and severe rheumatoid lung diseaseThorax19904585915962169654

- TishlerMGriefJFiremanEYaronMTopilskyMBronchoalveolar lavage – a sensitive tool for early diagnosis of pulmonary involvement in rheumatoid arthritisJ Rheumatol19861335475503735275

- ParkJHKimDSParkINPrognosis of fibrotic interstitial pneumonia: idiopathic versus collagen vascular disease-related subtypesAm J Respir Crit Care Med2007175770571117218621

- DevouassouxGCottinVLioteHCharacterisation of severe obliterative bronchiolitis in rheumatoid arthritisEur Respir J20093351053106119129282

- Rangel-MorenoJHartsonLNavarroCGaxiolaMSelmanMRandallTDInducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT) in patients with pulmonary complications of rheumatoid arthritisJ Clin Invest2006116123183319417143328

- YousemSAColbyTVCarringtonCBLung biopsy in rheumatoid arthritisAm Rev Respir Dis198513157707773873887

- KinoshitaFHamanoHHaradaHRole of KL-6 in evaluating the disease severity of rheumatoid lung disease: comparison with HRCTRespir Med200498111131113715526815

- ScottDGBaconPAResponse to methotrexate in fibrosing alveolitis associated with connective tissue diseaseThorax198035107257317466720

- CohenJMMillerASpieraHInterstitial pneumonitis complicating rheumatoid arthritis. Sustained remission with azathioprine therapyChest1977724521524908223

- ChangHKParkWRyuDSSuccessful treatment of progressive rheumatoid interstitial lung disease with cyclosporine: a case reportJ Korean Med Sci200217227027311961317

- SaketkooLAEspinozaLRRheumatoid arthritis interstitial lung disease: mycophenolate mofetil as an antifibrotic and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugArch Intern Med2008168151718171918695091

- VassalloRMattesonEThomasCFJrClinical response of rheumatoid arthritis-associated pulmonary fibrosis to tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitionChest200212231093109612226061

- BargagliEGaleazziMRottoliPInfliximab treatment in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis and pulmonary fibrosisEur Respir J200424470815459153

- OstorAJCrispAJSomervilleMFScottDGFatal exacerbation of rheumatoid arthritis associated fibrosing alveolitis in patients given infliximabBMJ20043297477126615564258

- VilleneuveESt-PierreAHaraouiBInterstitial pneumonitis associated with infliximab therapyJ Rheumatol20063361189119316622902

- Peno-GreenLLluberasGKingsleyTBrantleySLung injury linked to etanercept therapyChest200212251858186012426295

- HagiwaraKSatoTTakagi-KobayashiSHasegawaSShigiharaNAkiyamaOAcute exacerbation of preexisting interstitial lung disease after administration of etanercept for rheumatoid arthritisJ Rheumatol20073451151115417444583

- DixonWGHyrichKLWatsonKDLuntMSymmonsDPInfluence of anti-TNF therapy on mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics RegisterAnn Rheum Dis20106961086109120444754

- PrattDSSchwartzMIMayJJDreisinRBRapidly fatal pulmonary fibrosis: the accelerated variant of interstitial pneumonitisThorax1979345587593160092

- HakalaMPoor prognosis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis hospitalized for interstitial lung fibrosisChest19889311141183335140

- HubbardRVennAThe impact of coexisting connective tissue disease on survival in patients with fibrosing alveolitisRheumatology (Oxford)200241667667912048295

- Turner-WarwickMBurrowsBJohnsonACryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis: clinical features and their influence on survivalThorax19803531711807385089

- SaravananVKellyCASurvival in fibrosing alveolitis associated with rheumatoid arthritis is better than cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitisRheumatology (Oxford)2003424603604 author reply 604–605.12649414