Abstract

Background

Immunotherapy based on cytokine-induced killer cells or combination of dendritic cells and cytokine-induced killer cells (CIK/DC-CIK) showed promising clinical outcomes for treating esophageal cancer (EC). However, the clinical benefit varies among previous studies. Therefore, it is necessary to systematically evaluate the curative efficacy and safety of CIK/DC-CIK immunotherapy as an adjuvant therapy for conventional therapeutic strategies in the treatment of EC.

Materials and methods

Clinical trials published before October 2016 and reporting CIK/DC-CIK immunotherapy treatment responses or safety for EC were searched in Cochrane Library, EMBASE, PubMed, Wanfang and China National Knowledge Internet databases. Research quality and heterogeneity were evaluated before analysis, and pooled analyses were performed using random- or fixed-effect models.

Results

This research covered 11 trials including 994 EC patients. Results of this meta-analysis indicated that compared with conventional therapy, the combination of conventional therapy with CIK/DC-CIK immunotherapy significantly prolonged the 1-year overall survival (OS) rate, overall response rate (ORR) and disease control rate (DCR) (1-year OS: P=0.0005; ORR and DCR: P<0.00001). Patients with combination therapy also showed significantly improved quality of life (QoL) (P=0.02). After CIK/DC-CIK immunotherapy, lymphocyte percentages of CD3+ and CD3−CD56+ subsets (P<0.01) and cytokines levels of IFN-γ, -2, TNF-α and IL-12 (P<0.00001) were significantly increased, and the percentage of cluster of differentiation (CD)4+CD25+CD127− subset was significantly decreased, whereas analysis of CD4+, CD8+, CD4+/CD8+ and CD3+CD56+ did not show significant difference (P>0.05).

Conclusion

The combination of CIK/DC-CIK immunotherapy and conventional therapy is safe and markedly prolongs survival time, enhances immune function and improves the treatment efficacy for EC.

Introduction

Esophageal cancer (EC) is a global common cancer, with 450,000 new cases and 400,000 estimated deaths per year.Citation1,Citation2 The incidence of EC has increased exponentially over the past few decades and the 5-year survival rate remains bleak.Citation3 At present, surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy are most widely used for EC.Citation4 However, their application is limited by the failure to thoroughly eliminate tumor cells, drug resistance and other adverse effects.Citation5,Citation6 Therefore, a more effective and safer therapeutic method is urgently required.

In recent years, immunotherapy has been rising rapidly and is considered the fourth powerful therapeutic method after surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy.Citation6 Cancer immunotherapy is accomplished in multiple ways, including manipulation of the immune system through the use of immune agents, such as vaccines,Citation7 cytokines,Citation8 checkpoint inhibitors (including anti-programmed death 1 [PD-1]/PD-ligand 1 [PD-L1] antibodies and anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen (CTLA)-4 antibodies),Citation9,Citation10 kinase inhibitors (such as apatinib and gefitinib)Citation11,Citation12 and immune cells.Citation13–Citation19 However, their applications have the following hurdles. Simply activating the immunity via vaccination is not able to thoroughly eliminate tumor cells because cancer patients are usually in immunosuppression.Citation19 Promotion of molecule-targeted treatment for tumors is also confined only to cancer patients bearing specific antigen-expressing cells.Citation13 Notably, adoptive cellular immunotherapy has been flourishing in cancer treatment. Its effectiveness relies on the application of dendritic cells (DCs),Citation14 tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs),Citation15 natural killer (NK) cells,Citation16 cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs),Citation17 cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cellsCitation18 and other immune cells. CIK cells, which consist primarily of the CD3+CD56+ subset, are induced by interferon (IFN)-γ, interleukin (IL)-1, cluster of differentiation (CD)3 monoclonal antibodies (OKT3) and IL-2 in vitro.Citation5 Compared with other immune cells, CIK cells are easy to obtain from peripheral blood and umbilical cord blood mononuclear cells, and they possess higher in vitro proliferation capacity, stronger antitumor activity and broader antitumor spectrum.Citation6 The tumoricidal ability of CIK cells is implemented by inducing tumor cell apoptosis through direct contact and secretion of cytokines such as IL-2, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and IFN-γ.Citation20 CIK cells have shown promising prospects in immunotherapy for cancers. On the one hand, the cytotoxicity of CIK cells is not affected by immune inhibitors such as cyclosporin A (CsA) and FK506.Citation21 On the other hand, CIK cell-mediated cytotoxicity does not rely on the major histocompatibility complex (MHC). As in most cancers, these cells do not express MHC or human leukocyte antigen (HLA); this property of CIK cells is a great advantage over other immune cells in adoptive cell therapy.Citation22

DCs are the most potent antigen-presenting cells and are essential in CIK activation, proliferation, phenotype expression and cytokine secretion.Citation5,Citation23,Citation24 The cytotoxicity of CIK cells is remarkably enhanced when cocultured with DCs, indicated by the increased proportion of CD3+CD56+ cells and the improved levels of cytokines such as IL-2, IFN-γ, IL-12 and TNF-α.Citation6,Citation23 Meanwhile, cocultured DCs also downregulate the expression of negative regulatory factors, including transforming growth factor (TGF)-β and IL-10, as well as the proportion of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) among CIK cells, which suppress the antitumor activity of CIK.Citation5,Citation24 Several research reports have shown that the combination of DCs and CIKs (DC-CIK) is more effective and has indicated more promising clinical prospects than single CIK treatment.Citation6

In EC treatment, there are emerging data indicating CIK or DC-CIK (CIK/DC-CIK) immunotherapy in combination with conventional therapy exhibited better therapeutic efficacy than conventional therapy alone.Citation25–Citation37 However, CIK/DC-CIK immunotherapy clinical application is still in its infancy. In this research, we conducted a meta-analysis to investigate the efficacy and safety of CIK/DC-CIK combined with conventional therapy in comparison with conventional therapy alone for EC, in order to provide scientific evidence for future clinical trials.

Materials and methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

Literature reports were searched across Cochrane Library, EMBASE, PubMed, Wanfang and China National Knowledge Internet databases with the key terms “dendritic cells”, “immunotherapy”, “cytokine-induced killer cells” or “DC-CIK” combined with “esophageal cancer”. No language limits were applied. The initial search was performed in April 2016 and updated in October 2016.

Studies selected in our research were randomized controlled clinical trials for EC. The included studies were all performed with comparison between the combination of CIK/DC-CIK and conventional treatment (defined as combination therapy group) and conventional regimens alone (defined as conventional therapy-alone group).

Data collection and quality assessment

Two authors independently searched and collected literatures from the databases according to our inclusion criteria, and they extracted the data from all the selected articles. Discrepancy was resolved by discussion with a third author. The collected information included the first authors’ names, the years of publication, the numbers of subjects, patient ages, tumor stages, experiment regimens, in vitro cell culture conditions and dosages of the utilized immune cells. The quality of the included articles was evaluated according to the Cochrane Handbook.Citation38

Definition of outcome measurements

Treatment efficacy was assessed in terms of overall survival (OS), overall response rate (ORR; ORR = complete response rate + partial response rate), disease control rate (DCR; DCR = complete response rate + partial response rate + stable disease rate), patients’ quality of life (QoL) and adverse events. OS was defined as the length of time from the initiation of treatment to death from any cause.Citation39 The immune function of EC patients before and after treatment was determined by the status of the lymphocyte subsets (CD3+, CD4+, CD8+, CD3-CD56+, CD3+CD56+ and CD4+CD25+CD127−) and cytokine secretion (IFN-γ, IL-2, TNF-α and IL-12).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Review Manager version 5.2 provided by Cochrane Collaboration. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Heterogeneity among the studies was assessed to determine the most suitable model.Citation40 A random-effects method was applied when heterogeneity existed; otherwise, a fixed-effects method was used. Cochran’s Q-test was performed in order to evaluate homogeneity among studies, and I2<50% or P>0.1 was considered homogeneous. Odds ratios (ORs) were the principal measurements for therapeutic effects and were presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

Search results

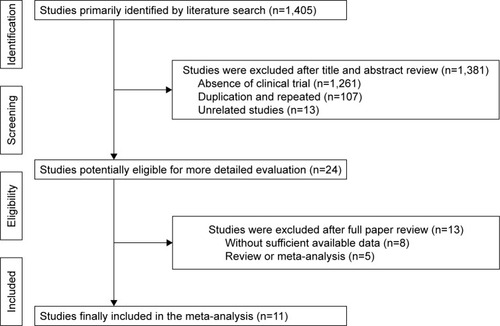

A total of 1,405 articles were identified by initial retrieval. After title and abstract review, 1,381 articles were excluded because they did not focus on clinical trials (n=1,261), were in duplication and repetition (n=107) or were unrelated studies (n=13), and 24 studies remained as potentially relevant. After reading the full texts, 8 papers with insufficient data and 5 reviews or meta-analyses were excluded. Finally, 11 trials that included 994 EC patients met the inclusion criteria for our meta-analysis ().

Patient characteristics

In all, 11 eligible trials including 994 EC patients were included in this analysis. All trials were conducted in mainland China. In total, 501 patients were treated by CIK/DC-CIK in combination with conventional therapy (combination therapy), while 493 patients were treated by conventional therapy alone. Detailed clinical information of the trials is presented in . DC and CIK cells used in the 11 trials were all obtained from autologous peripheral blood. In 4 trials, DC-CIK immunotherapy was applied, whereas in the other 7 trials, only CIK cells were used. In most studies, patients were transfused with >1×109 immune cells, and other studies did not provide accurate cell numbers. Tumor size and injection modes were not analyzed in this article due to the lack of sufficient data in the included studies.

Table 1 Clinical information from the eligible trials used in the meta-analysis

Quality assessment

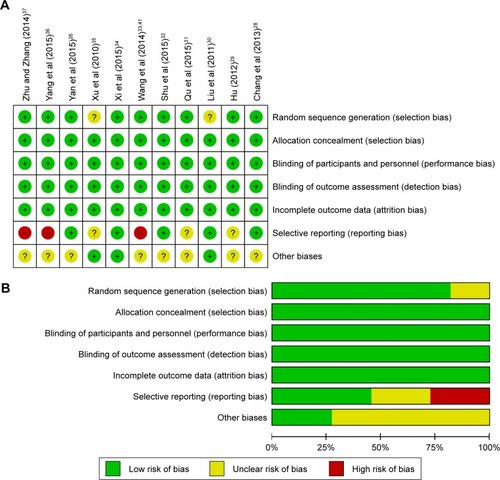

The assessment for risk of bias is shown in . The quality of the involved studies ranged from moderate to high: 9 studies were low in risk of bias, while the other 2 studies did not have a clear description of the randomization process. The allocation, performance, detection and attrition risks of the involved studies were low; 3 trials were considered to be of unclear risk owing to their selective reporting, while 3 other studies were considered as high risk as they did not show primary outcome data.

Efficacy assessments

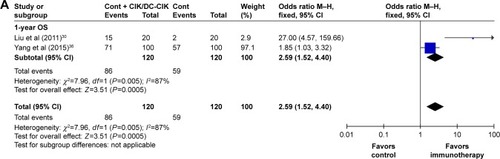

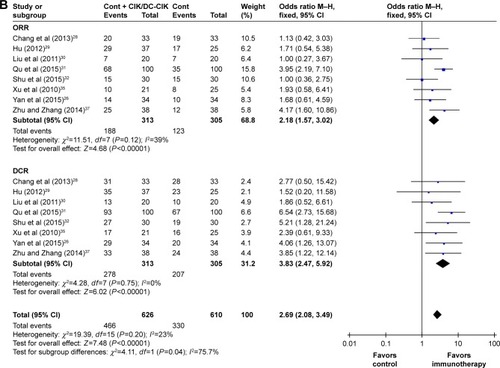

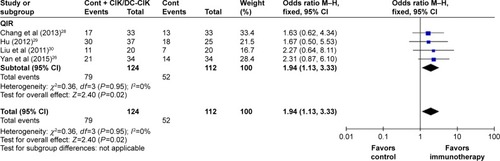

This analysis indicated that OS, ORR and DCR were significantly improved in patients who underwent combination therapy compared to those treated by conventional therapy alone (, 1-year OS: OR =2.59, 95% CI =1.52–4.40, P=0.0005; ORR: OR =2.18, 95% CI =1.57−3.02, P<0.00001; DCR: OR =3.83, 95% CI =2.47−5.92, P<0.00001). Moreover, the pooled results showed that patients in the combination therapy group had significantly improved QoL (, QoL: OR =1.94, 95% CI =1.13−3.33, P=0.02). The fixed-effects model was applied in this analysis considering the slightly significant heterogeneity.

Figure 3 Forest plots of the comparisons of (A) OS and (B) ORR and DCR.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CIK/DC-CIK, immunotherapy with cytokine-induced killer cells or combination of dendritic cells and cytokine-induced killer cells; Cont, conventional therapy; DCR, disease control rate; M–H, Mantel–Haenszel method; ORR, overall response rate; OS, overall survival.

Figure 4 Forest plot for the comparison of QIR.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CIK/DC-CIK, immunotherapy with cytokine-induced killer cells or combination of dendritic cells and cytokine-induced killer cells; Cont, conventional therapy; M–H, Mantel–Haenszel method; QIR, quality-of-life improved rate.

Immune function evaluation

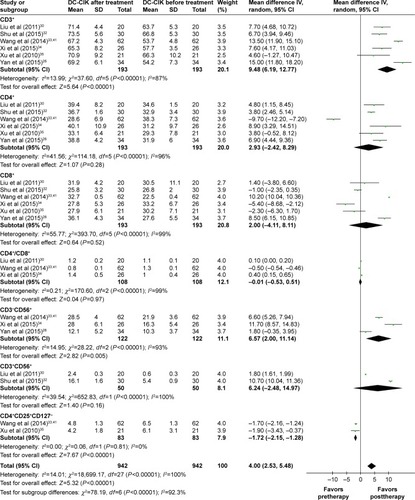

The immune status of patients was examined before and after the treatment. After CIK/DC-CIK treatment, the proportions of CD3+ and CD3−CD56+ in patients were significantly increased (, CD3+: OR =9.48, 95% CI =6.19−12.77, P<0.00001; CD3−CD56+: OR =6.57, 95% CI =2.00−11.14, P=0.005), CD4+CD25+CD127− proportion was significantly decreased (CD4+CD25+CD127−: OR =−1.72, 95% CI =−2.15 to −1.28, P<0.00001), whereas the proportions of CD4+, CD8+ and CD3+CD56+ and the CD4+/CD8+ ratio did not show much differences (CD4+: OR =2.93, 95% CI =−2.42 to 8.29, P=0.28; CD8+: OR =2.00, 95% CI =−4.11 to 8.11, P=0.52; CD4+/CD8+: OR =−0.01, 95% CI =−0.53 to 0.51, P=0.97; CD3+CD56+: OR =6.24, 95% CI =−2.48 to 14.97, P=0.16).

Figure 5 Forest plot of immunophenotype assessment before and after treatment with CIK/DC-CIK.

Abbreviations: CD, cluster of differentiation; CI, confidence interval; CIK/DC-CIK, immunotherapy with cytokine-induced killer cells or combination of dendritic cells and cytokine-induced killer cells; SD, standard deviation.

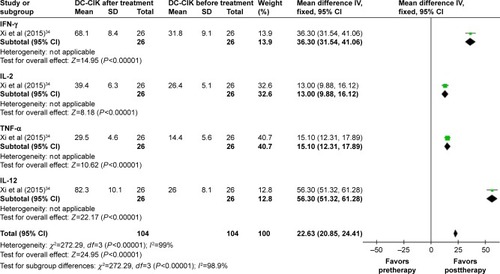

On the other hand, patients’ cytokines levels were also significantly increased after CIK/DC-CIK therapy (, IFN-γ: OR =36.30, 95% CI =31.54−41.06, P<0.00001; IL-2: OR =13.00, 95% CI =9.88−16.12, P<0.00001; TNF-α: OR =15.10, 95% CI =12.31−17.89, P<0.00001; IL-12: OR =56.30, 95% CI =51.32−61.28, P<0.00001).

Figure 6 Forest plot of cytokines before and after treatment with CIK/DC-CIK.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CIK/DC-CIK, immunotherapy with cytokine-induced killer cells or combination of dendritic cells and cytokine-induced killer cells; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; SD, standard deviation; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Assessment of adverse events

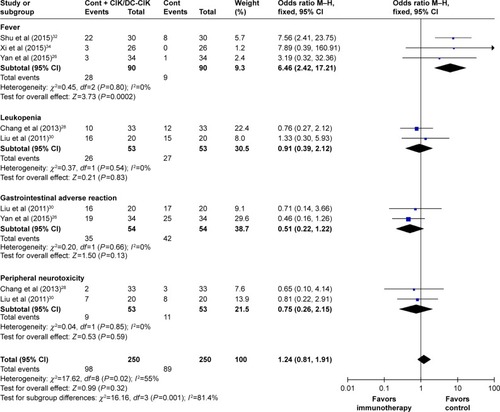

The safety of CIK/DC-CIK therapy in the treatment of EC was evaluated in this meta-analysis. As shown in , no serious adverse events or death occurrence was reported in the involved literature. The most common side effect was fever, which subsided naturally within 24 hours. Except the higher incidence of fever in the combination therapy group than in the conventional therapy group (fever: OR =6.46, 95% CI =2.42–17.21, P=0.0002), no significant difference was observed in terms of leukopenia, gastrointestinal adverse reaction and peripheral neurotoxicity (leukopenia: OR =0.91, 95% CI =0.39–2.12, P=0.83; gastrointestinal adverse reaction: OR =0.51, 95% CI =0.22–1.22, P=0.13; peripheral neurotoxicity: OR =0.75, 95% CI =0.26–2.15, P=0.59).

Figure 7 Forest plot of the comparison of adverse effects.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CIK/DC-CIK, immunotherapy with cytokine-induced killer cells or combination of dendritic cells and cytokine-induced killer cells; Cont, conventional therapy; M–H, Mantel–Haenszel method.

Discussion

Clinical trials have been conducted on CIK/DC-CIK immunotherapy for the treatment of EC.Citation26,Citation31 In this study, we performed an extensive online search, followed by rigorous meta-analysis, in order to evaluate its therapeutic efficacy and safety. Our meta-analysis revealed that the combination of CIK/DC-CIK immunotherapy and conventional therapy was a safe and effective regimen for the treatment of EC. Compared to conventional regimens alone, patients with combination therapy demonstrated higher OS rate, ORR and DCR, as well as improved immune function and QoL.

This study confirmed the safety of CIK/DC-CIK immunotherapy for EC patients, and the adverse events caused were tolerated by all patients. Fever was the most common side effect when patients were treated with combination conventional-plus-CIK/DC-CIK therapy, and its incidence was higher than when treated by conventional therapy alone (P<0.05). No significant difference was observed in terms of other adverse events, such as leukopenia, gastrointestinal adverse reaction and peripheral neurotoxicity between the 2 groups (P>0.05). CIK/DC-CIK immunotherapy enhanced the efficiency of conventional therapy in the treatment of EC. Compared with the conventional therapy-alone group, 1-year OS, ORR and DCR of patients in the combination therapy group were improved remarkably (P<0.01). Moreover, the combination therapy improved patients’ QoL (P<0.05) by relieving pain, reducing fatigue and insomnia as well as improving appetite.

Health status is closely related to human immune function, and a healthy human body has a robust immune system to detect and kill cancer cells.Citation5,Citation6 However, the immune function in cancer patients is compromised, and the percentage of T-lymphocyte subsets in the peripheral blood is usually disordered.Citation5,Citation6 Immune system reconstruction is one of the key factors to effectively treat malignant tumors.Citation6 The antitumor activity of CIK/DC-CIK is mainly attributed to CD3−CD56+ and CD3+CD56+ cells.Citation41 Our analysis indicated that the proportions of CD3+, CD3−CD56+ and CD3+CD56+ T cells were increased after CIK/DC-CIK treatment, although the percentages of CD3+CD56+ T cells did not reach statistical significance. However, no significant differences were found in the percentages of CD4+, CD8+ and CD4+/CD8+ ratios before and after immunotherapy. This may be caused by the different time points when the T-lymphocyte subsets were tested in these trials.Citation6,Citation19,Citation42,Citation43 Our analysis revealed a decreased proportion of CD4+CD25+ CD127− Tregs. This is consistent with a previous study that illustrated a negative role of Tregs in the implementation of CIK’s antitumor activity.Citation44 Besides, the balance between the 2 helper T-cell (Th1 and Th2 cells) classes is also important in immunotherapy.Citation5,Citation41 Th1 cells enhance killer cells’ cytotoxicity and trigger delayed-type hypersensitivity, whereas Th2 cells are associated with tumor immune escape.Citation5,Citation45 Our analysis showed that after CIK/DC-CIK immunotherapy, the levels of Th1 cytokines, including IFN-γ, IL-2, TNF-α and IL-12, were significantly increased (P<0.00001), indicating a strong association between Th1 cytokines and efficacy of CIK/DC-CIK immunotherapy. Although our results indicated that CIK/DC-CIK immunotherapy enhanced the immune function in EC patients, the exact underlying mechanism of action of CIK/DC-CIK immunotherapy on hosts’ immune system remains unclear, which requires further studies on its mechanism.

This meta-analysis has some limitations. First of all, although CIK/DC-CIK immunotherapy has been applied to treat malignancies worldwide for its outstanding curative effects,Citation46–Citation48 all of the clinic trials that met our inclusion criteria were carried out in the Chinese population. We will follow updated publications on CIK/DC-CIK immunotherapy for EC conducted both in China and other countries and subsequently perform further systematic research on it. Moreover, the analysis performed in this study was not subjected to an open external evaluation procedure, which may lead to an overestimation of treatment effects. In addition, insufficient information regarding some patients, small sample sizes and other variables may have introduced bias into our conclusions. Besides, the clinical application of adoptive CIK/DC-CIK immunotherapy was limited due to the low specificity, although it is a promising strategy for the treatment of malignant tumors. Many new methods of immunotherapy, such as chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells and T-cell receptor-modified T cells, have been developed currently,Citation49–Citation51 limiting the importance of this study.

Conclusion

Taken together, this meta-analysis suggests that the combination of CIK/DC-CIK immunotherapy and conventional regimens is safe and effective in treating patients with EC, with markedly prolonged survival time, enhanced immune function and improved therapeutic efficacy. Considering the limitations of our research, further analysis on studies conducted in countries other than China with larger sample sizes and going through open external evaluation procedure will be valuable to verify the credibility of our conclusions.

Author contributions

Changhui Zhou and Yingxin Zhang conceived and designed the experiments. Yan Liu, Ying Mu and Shaoda Ren performed the experiments. Weihua Wang and Jiaping Xie analyzed the data. Yan Liu and Ying Mu drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

This research work was supported by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong (No 2015ZRA15027 to Changhui Zhou), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No 81600087 to Shaoda Ren), Natural Science Foundation of Shandong (No ZR2016HB45 to Shaoda Ren), Medical Science Foundation of Shandong (No 2014WS0300 to Weihua Wang) and Wu Jieping Medical Foundation (No 320.6750.15043 to Weihua Wang).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- LvLHuWRenYWeiXMinimally invasive esophagectomy versus open esophagectomy for esophageal cancer: a meta-analysisOnco Targets Ther201696751676227826201

- VisserEFrankenIABrosensLARuurdaJPvan HillegersbergRPrognostic gene expression profiling in esophageal cancer: a systematic reviewOncotarget2017835566557727852047

- MannathJRagunathKRole of endoscopy in early oesophageal cancerNat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol2016131272073027807370

- GoodeEFSmythECImmunotherapy for gastroesophageal cancerJ Clin Med201651084

- MuYZhouCHChenSFEffectiveness and safety of chemotherapy combined with cytokine-induced killer cell/dendritic cell-cytokine-induced killer cell therapy for treatment of gastric cancer in China: a systematic review and meta-analysisCytotherapy20161891162117727421742

- ZhouCLLiuDLLiJChemotherapy plus dendritic cells co-cultured with cytokine-induced killer cells versus chemotherapy alone to treat advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysisOncotarget2016752865008651027863436

- SiYDengZLanGThe safety and immunological effects of rAd5-EBV-LMP2 vaccine in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients: a phase I clinical trial and two-year follow-upChem Pharm Bull (Tokyo)20166481118112327477649

- PassalacquaRCaminitiCButiSAdjuvant low-dose interleukin-2 (IL-2) plus interferon-alpha (IFN-alpha) in operable renal cell carcinoma (RCC): a phase III, randomized, multicentre trial of the Italian Oncology Group for Clinical Research (GOIRC)J Immunother201437944044725304727

- ZhangTXieJAraiSThe efficacy and safety of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies for treatment of advanced or refractory cancers: a meta-analysisOncotarget2016745730687307927683031

- WeberJSD’AngeloSPMinorDNivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma who progressed after anti-CTLA-4 treatment (CheckMate 037): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trialLancet Oncol201516437538425795410

- LiJQinSXuJRandomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial of apatinib in patients with chemotherapy-refractory advanced or metastatic adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junctionJ Clin Oncol201634131448145426884585

- BoyeMWangXSrimuninnimitVFirst-line pemetrexed plus cisplatin followed by gefitinib maintenance therapy versus gefitinib monotherapy in East Asian never-smoker patients with locally advanced or metastatic nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer: quality of life results from a randomized phase III trialClin Lung Cancer201617215016026809984

- StanculeanuDLDanielaZLazescuABunghezRAnghelRDevelopment of new immunotherapy treatments in different cancer typesJ Med Life20169324024827974927

- PeoplesGEGurneyJMHuemanMTClinical trial results of a HER2/neu (E75) vaccine to prevent recurrence in high-risk breast cancer patientsJ Clin Oncol200523307536754516157940

- DudleyMEGrossCASomervilleRPRandomized selection design trial evaluating CD8+-enriched versus unselected tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes for adoptive cell therapy for patients with melanomaJ Clin Oncol201331172152215923650429

- ZhaoZLiaoHJuYEffect of compound Kushen injection on T-cell subgroups and natural killer cells in patients with locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer treated with concomitant radiochemotherapyJ Tradit Chin Med2016361141826946613

- ChiaWKTeoMWangWWAdoptive T-cell transfer and chemotherapy in the first-line treatment of metastatic and/or locally recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinomaMol Ther201422113213924297049

- JäkelCEVogtAGonzalez-CarmonaMASchmidt-WolfIGHClinical studies applying cytokine-induced killer cells for the treatment of gastrointestinal tumorsJ Immunol Res20142014112

- ShiLRZhouQWuJEfficacy of adjuvant immunotherapy with cytokine-induced killer cells in patients with locally advanced gastric cancerCancer Immunol Immunother201261122251225922674056

- LiGXZhaoSSZhangXGComparison of the proliferation, cytotoxic activity and cytokine secretion function of cascade primed immune cells and cytokine-induced killer cells in vitroMol Med Rep20151222629263525955083

- MehtaBASchmidt-WolfIGWeissmanILNegrinRSTwo pathways of exocytosis of cytoplasmic granule contents and target cell killing by cytokine-induced CD3+ CD56+ killer cellsBlood1995869349334997579455

- ZhuYZhangHLiYEfficacy of postoperative adjuvant transfusion of cytokine-induced killer cells combined with chemotherapy in patients with colorectal cancerCancer Immunol Immunother201362101629163523974720

- WeiXCYangDDHanXRBioactivity of umbilical cord blood dendritic cells and anti-leukemia effectInt J Clin Exp Med2015810197251973026770637

- LiHRenXBZhangPAnXMLiuHHaoXS树突状细胞对CIK细 胞中CD4+CD25+ T细胞数量及免疫调节作用的影响 [Dendritic cells reduce the number and function of CD4+CD25+ cells in cytokine-induced killer cells]Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi200585443134313816405818

- GaoDQLiCYXieXHAutologous tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cell immunotherapy with cytokine-induced killer cells improves survival in gastric and colorectal cancer patientsPLoS One201494e9388624699863

- YanLWuMBaNEfficacy of dendritic cell-cytokine-induced killer immunotherapy plus intensity-modulated radiation therapy in treating elderly patients with esophageal carcinomaGenet Mol Res201514189890525730028

- ZhangZWangLPLuoZZEfficacy and safety of cord blood-derived cytokine-induced killer cells in treatment of patients with malignanciesCytotherapy20151781130113825963952

- ChangZGXuQXMaLHeLMClinical observation of cytokine induced killer cell intravenous transfusion combined with chemotherapy in treatment of advanced esophageal cancerShandong Med J201353235354

- HuYQEffect of herb plus adoptive immunotherapy with cytokine induced killer cells on cellular immunity of patients with advanced esophageal carcinomaJ Bengbu Med Coll201237910621066

- LiuGJMeiJZXiaoPLiRJLiMEfficacy of chemotherapy combined with cytokine-induced killer cells in the treatment of advanced esophageal carcinomaJ Zhengzhou Univ2011462169173

- QuWFZhangWMDingXYIL-12 induced CIK cells combined with chemotherapy improve immune function and efficacy in patients with esophageal carcinomaShi Jie Hua Ren Xiao Hua Za Zhi2015232845534557

- ShuXLiGXZhuXLLiGGanQWangZYAutologous cytokine-induced killer cells combined with chemoradiation in the treatment of locally advanced esophageal carcinoma: a randomized control studyMod Oncol2015231013761380

- WangHShuWMaoGHZhangYJShiTLEffect of dendritic cell-cytokine-induced killer cell adoptive immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy on T cell subsets of patients with esophageal cancerContemp Med2014202813

- XiXXLvBHYeTChenRXuXEffect of DC-CIK cells’ biotherapy in comprehensive therapy of esophagus cancer: a randomized controlled trialChin J Clin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg2015228765769

- XuBLGaoQLFanRHLiuXGuoJDZhangCJClinical effects on chemotherapy combined with CIK for patients with advanced oesophageal carcinomaHenan Med Res2010193315320

- YangBLiWSunXAChenYMThe clinical efficacy of endoscopic implantation with chemotherapeutic slow-release combined with DC-CIK immune cells infusion for patients with obstructive esophageal cancersChina J Endoscopy2015215483486

- ZhuHPZhangQAAnalysis of the effect of injection in treatment of advanced esophageal cancer paclitaxel cisplatin regimen combined with autologous CIK cellsChin J Clin Oncol Rehabil2014217837839

- ZengXZhangYKwongJSThe methodological quality assessment tools for preclinical and clinical studies, systematic review and meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline: a systematic reviewJ Evid Based Med20158121025594108

- HanRXLiuXPanPJiaYJYuJCEffectiveness and safety of chemotherapy combined with dendritic cells co-cultured with cytokine-induced killer cells in the treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysisPLoS One201499e10895825268709

- JacksonDWhiteIRRileyRDQuantifying the impact of between-study heterogeneity in multivariate meta-analysesStat Med201231293805382022763950

- WangZXCaoJXWangMAdoptive cellular immunotherapy for the treatment of patients with breast cancer: a meta-analysisCytotherapy201416793494524794183

- MilasieneVStratilatovasENorkieneVThe importance of T-lymphocyte subsets on overall survival of colorectal and gastric cancer patientsMedicina (Kaunas)200743754855417768369

- ChoMYJohYGKimNRT-lymphocyte subsets in patients with AJCC stage III gastric cancer during postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy. American Joint Committee on CancerScand J Surg200291217217712164518

- TaoQWangHZhaiZTargeting regulatory T cells in cytokine-induced killer cell cultures (Review)Biomed Rep20142331732024748966

- MuYWangWHXieJPZhangYXYangYPZhouCHEfficacy and safety of cord blood-derived dendritic cells plus cytokine-induced killer cells combined with chemotherapy in the treatment of patients with advanced gastric cancer: a randomized Phase II studyOnco Targets Ther201694617462727524915

- OliosoPGiancolaRDi RitiMContentoAAccorsiPIaconeAImmunotherapy with cytokine induced killer cells in solid and hematopoietic tumours: a pilot clinical trialHematol Oncol200927313013919294626

- LeeJHLimYSLimYSAdjuvant immunotherapy with autologous cytokine-induced killer cells for hepatocellular carcinomaGastroenterology201514871383.e61391.e625747273

- IntronaMPievaniABorleriGFeasibility and safety of adoptive immunotherapy with CIK cells after cord blood transplantationBiol Blood Marrow Transplant201016111603160720685246

- MaYZhangZTangLCytokine-induced killer cells in the treatment of patients with solid carcinomas: a systematic review and pooled analysisCytotherapy201214448349322277010

- ZhangTCaoLXieJEfficiency of CD19 chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells for treatment of B cell malignancies in phase I clinical trials: a meta-analysisOncotarget2015632339613397126376680

- KatzSCBurgaRAMcCormackEPhase I hepatic immunotherapy for metastases study of intra-arterial chimeric antigen receptor-modified T-cell therapy for CEA+ liver metastasesClin Cancer Res201521143149315925850950