Abstract

Objectives

Nonadherence to prescription medications has been shown to be significantly influenced by three key medication-specific beliefs: patients’ perceived need for the prescribed medication, their concerns about the prescribed medication, and perceived medication affordability. Structural equation modeling was used to test the predictors of these three proximal determinants of medication adherence using the proximal–distal continuum of adherence drivers as the organizing conceptual framework.

Methods

In Spring 2008, survey participants were selected from the Harris Interactive Chronic Illness Panel, an internet-based panel of hundreds of thousands of adults with chronic disease. Respondents were eligible for the survey if they were aged 40 years and older, resided in the US, and reported having at least one of six chronic diseases: asthma, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, osteoporosis, or other cardiovascular disease. A final sample size of 1072 was achieved. The proximal medication beliefs were measured by three multi-item scales: perceived need for medications, perceived medication concerns, and perceived medication affordability. The intermediate sociomedical beliefs and skills included four multi-item scales: perceived disease severity, knowledge about the prescribed medication, perceived immunity to side effects, and perceived value of nutraceuticals. Generic health beliefs and skills consisted of patient engagement in their care, health information-seeking tendencies, internal health locus of control, a single-item measure of self-rated health, and general mental health. Structural equation modeling was used to model proximal–distal continuum of adherence drivers.

Results

The average age was 58 years (range = 40–90 years), and 65% were female and 89% were white. Forty-one percent had at least a four-year college education, and just under half (45%) had an annual income of $50,000 or more. Hypertension and hyperlipidemia were each reported by about a quarter of respondents (24% and 23%, respectively). A smaller percentage of respondents had osteoporosis (17%), diabetes (15%), asthma (13%), or other cardiovascular disease (8%). Three independent variables were significantly associated with the three proximal adherence drivers: perceived disease severity, knowledge about the medication, and perceived value of nutraceuticals. Both perceived immunity to side effects and patient engagement was significantly associated with perceived need for medications and perceived medication concerns.

Conclusion

Testing the proximal–distal continuum of adherence drivers shed light on specific areas where adherence dialogue and enhancement should focus. Our results can help to inform the design of future adherence interventions as well as the content of patient education materials and adherence reminder letters. For long-term medication adherence, patients need to autonomously and intrinsically commit to therapy and that, in turn, is more likely to occur if they are both informed (disease and medication knowledge and rationale, disease severity, consequences of nonadherence, and side effects) and motivated (engaged in their care, perceive a need for medication, and believe the benefits outweigh the risks).

Introduction

Over the past 40 years, numerous conceptual models have been proposed to explain medication nonadherence.Citation1 A short listing of models that have been tested in relation to medication adherence include the Health Belief Model,Citation2 the Theory of Reasoned Action,Citation3 the Theory of Planned Behavior,Citation4 the Transtheoretical Model,Citation5 the Necessity-Concerns Framework,Citation6 the Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills model,Citation7 and the Information-Motivation-Strategy model.Citation8 Most of these frameworks belong to the family of models subsumed under social-cognitive theory,Citation1 and these models have incrementally built on the conceptual and empirical learning of one another. At the heart of all of these frameworks, as well as others, are two guiding assumptions: (1) individuals make decisions about prescription medications (ie, patients do not passively and reflexively obey physician recommendations about prescription medications); and (2) medication adherence is influenced by an array of patient beliefs, attitudes, skills, and experiences.

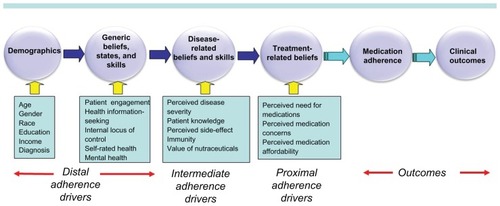

In 2009, the Proximal–Distal Continuum of Adherence Drivers model was proposed.Citation9 In the proximal–distal continuum, it was asserted that some adherence determinants are nearer or closer to patients’ medication-taking decisions (proximal) while others are more removed (further from) patients’ adherence decisions. The aim of the proximal–distal continuum was to organize the numerous hypothesized medication adherence drivers along an etiological continuum of determinants ranging from those shown to have strong empirical relationships with adherence (proximal drivers) to those with weaker relationships (distal drivers). In short, the proximal–distal continuum consists of an etiological hierarchy of hypothesized adherence drivers in order to account for medication adherence in a multifactorial manner.

The proximal–distal continuum is based upon three fundamental tenets. First, an adherent “personality” does not exist – the same individual can be adherent to one medication, not fill a second medication prescription, decide to stop taking a third medicine without the advice of their provider, and be careless taking a fourth medication.Citation9 A growing body of research has demonstrated that individual patients have different adherence patterns and levels for assorted medications, both within a therapeutic classCitation10–Citation12 as well as across therapeutic areas.Citation13–Citation16 Intraindividual variability in medication taking occurs because patients have different beliefs about different prescribed medications and their attendant diagnosed conditions. Second, patient beliefs, skills, and experiences that influence medication adherence can be either specific to a prescribed medication or disease or they can be generic in nature (ie, nonspecific to a prescribed medication or disease). In general, patient beliefs, skills, and experiences specific to a prescribed medication or disease tend to be more predictive of adherence than generic psychosocial beliefs and skills.Citation9,Citation17–Citation21 Third, for many patients, a new diagnosis and the attendant prescribed therapy represents uncertainty and is a threat to the status quo.Citation22 The short-term benefits of prescription-medication therapy can seem intangible to patients, especially to those with asymptomatic chronic disease. The long-term benefits of prescription medications are probabilistic and can be so distant in the future that patients may heavily discount them. Viewed through the uncertainty lens, nonadherence can make sense from the patient perspective because taking prescription medications represents a risky prospect in the short term (short-term financial, psychological, and opportunity costs, and risk of side effects) with uncertain long-term benefits (probabilistic reductions in mortality, morbidity, and complications) compared to the status quo (health as it is).Citation23

At the proximal end of the continuum are patients’ beliefs about the prescribed medication (). Research over the past 20 years has consistently demonstrated that patients’ beliefs about a prescribed medication are potent predictors of medication adherence. Next, etiologically, are patients’ sociomedical and disease-related beliefs, skills, and experiences which are hypothesized to be direct determinants of patients’ proximal medication beliefs. Patients’ generic beliefs, skills, and experiences are hypothesized to directly influence the disease-related and sociomedical beliefs. Finally, the most distal variables encompass demographic characteristics. Meta-analytic research has demonstrated weak associations between sociodemographic characteristics and adherence.Citation24

A large body of research has provided evidence about the relative influence of the myriad adherence drivers potentially subsumed under the proximal–distal continuum. The vast majority of these studies have examined medication adherence as the outcome variable. However, few studies have modeled the determinants of proximal medication beliefs – beliefs demonstrated by past research to be powerful predictors of medication adherence. Nonadherence to prescription medications has been shown to be significantly influenced by three key medication-specific beliefs: patients’ perceived need for the prescribed medication,Citation9,Citation18,Citation19,Citation25–Citation37 their concerns about the prescribed medication,Citation9,Citation18,Citation19,Citation26,Citation29,Citation30,Citation33,Citation34,Citation38–Citation47 and perceived medication affordability.Citation9,Citation48–Citation55 We used structural equation modeling (SEM) to test the predictors of these three proximal determinants of medication adherence. The goal of testing the proximal–distal continuum was to shed light on the origins of the three key proximal medication beliefs. This information can contribute insights as to how future adherence interventions may be made more efficacious by identifying underlying mechanisms influencing perceived need for medications, perceived medication concerns, and perceived medication affordability.

Methods

Study design

Sampling procedure

As described in detail elsewhere,Citation9 in Spring 2008, survey participants were selected from the Harris Interactive Chronic Illness Panel, an internet-based panel of hundreds of thousands of adults with chronic disease. Respondents were eligible for the survey if they were aged 40 years and older, resided in the US, and reported having at least one of six chronic diseases prevalent among US adults: asthma, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, osteoporosis, or other cardiovascular disease (CVD) (eg, angina, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure). The six chronic diseases reflect a mix of symptomatic and asymptomatic conditions. They are some of the most highly prevalent conditions in the USCitation56 and are associated with a significant clinical and economic burden for the US health care system.Citation57 If eligible respondents reported more than one of the six target conditions, one was randomly selected as the index (study) disease. Panel members responding to an e-mail invitation were instructed to read the informed consent form and click on yes if they agreed to participate. The protocol for the survey was approved by the Essex Internal Review Board. A 26.5% survey contact rate (per standards recommended by the American Association for Public Opinion Research)Citation58 was achieved. A total of 1072 adults completed the survey.

Survey content

The proximal, intermediate, and distal variables were all collected during a single survey administration. The proximal medication beliefs were measured by three multi-item scales: perceived need for medications (k = 12, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.96, illustrative item: “I am convinced of the importance of my prescription medication.”);Citation9 perceived medication concerns (k = 10, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90 items, illustrative item: “I worry that my prescription medication will do more harm than good to me.”);Citation9 and perceived medication affordability (k = 7, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.97, illustrative item “I feel financially burdened by my out-of-pocket expenses for my prescription medication.”).Citation9 The intermediate disease-related and sociomedical beliefs and skills included four multi-item scales: perceived disease severity (k = 3, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.76, illustrative item: “I think that my condition is severe.”); knowledge about the index medication (k = 9, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.92, illustrative item: “I understand exactly what the medication prescribed for me will do for me.”); perceived immunity to side effects (k = 3, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90, illustrative item: “My chances of experiencing negative side effects from a prescription drug are high.”); and perceived value of nutraceuticals (ie, vitamins, minerals, and supplements) (k = 7, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.92, illustrative item: “For me personally, I believe that vitamin, mineral, and herbal supplements can achieve better health results than prescription drugs can.”). Generic health beliefs and skills were measured by patient engagement in their care (k = 14, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.97, illustrative item “My doctor and I have a real partnership in my health care.”); health information-seeking tendencies (k = 5, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.91, illustrative item: “I actively seek out information on my illnesses.”); internal health locus of control using Wallston’s measure (k = 10, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.89);Citation59 general mental health using the Mental Health Inventory (k = 5, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.88);Citation60 and a single-item measure of self-rated health (the “excellent-to-poor” item from the Medical Outcomes Study [MOS] Short-Form Health Survey [SF-36]).Citation60 Evidence of the validity of these measures vis á vis the criterion of medication adherence has been previously published.Citation9,Citation61–Citation64 With the exception of the Mental Health Inventory (a six-point scale ranging from “all of the time” to “none of the time”), health locus of control (a six-point scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”), and the “excellent-to-poor” item (excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor), all items used a six-point categorical rating scale ranging from “agree completely” to “disagree completely.” Each multi-item scale was computed using Likert’s methodCitation65 of summated ratings in which each item is equally weighted and raw item scores are summed into a scale score. All scale scores were linearly transformed to a 0–100 metric, with 100 representing the most favorable belief or state, 0 the least favorable, and scores in between representing the percentage of the total possible score.

Demographic variables were included in the model. Age was measured as a continuous variable. Gender and race were coded as 1 = female vs 0 = male and 1 = white vs 0 = nonwhite, respectively. Education was measured as a six-level interval variable with higher values indicating higher education. Income was measured with an 11-level interval variable with higher values indicating higher income. Each disease indicator was coded as 1 = present vs 0 = not present with hypertension selected as the reference group because it had the largest sample size of the six diseases.

Statistical analysis

Survey noncontact analysis

Logistic regression was used to assess differences between Chronic Illness Panel members with valid e-mail addresses who did and did not respond to the survey invitation (ie, survey noncontact bias per standards recommended by the American Association for Public Opinion Research).Citation58 Independent variables for the logistic regression were age, gender, race, education, income, and geographic region of residence.

Structural equation modeling (SEM)

SEM was used in this analysis because some variables were both endogenous and exogenous, and traditional multivariate regression would not efficiently test the path relationships in one model. Twelve equations (three equations with the proximal beliefs as dependent variables, four equations with the intermediate beliefs and skills as dependent variables, and five equations with the generic beliefs, states, and skills as the dependent variables) were specified to represent the hypothesized relationships among the variables, which were treated as measured indicators of respondents’ beliefs, states, and skills (see ). A single multivariate path model of these structural equationsCitation66–Citation69 was estimated by modeling the covariance matrix among the observed variables. As shown in , the three proximal beliefs were specified to be associated with the intermediate, disease-related beliefs and skills, which in turn were associated with the distal generic beliefs and skills, and in turn with demographic characteristics.

SEM model fitting was performed in two steps. The first step was the execution of a full model to include all variables specified in the proximal–distal continuum (). The final model, presented in –, includes only statistically-significant variables. Statistical significance, goodness-of-fit indices, and modification indices were used to guide the final model.

Table 2 Standardized path loadings of path model in predicting proximal beliefs

Table 4 Standardized path loadings of path model in predicting distal beliefs

All available data were used in the analysis and were used as input into Mplus© software (version 6.1; Muthén and Muthén, Los Angeles, CA).Citation70 Full information maximum likelihood with the Mplus MLR estimator was used to estimate path coefficients and standard errors robust to nonnormality. The chi-square test and three fit indices (comparative fit index [CFI], root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA], and the standardized root mean square residual [SRMR]) provided an assessment of model fit. Good model fit was identified with chi-square ratio < 3.0, CFI > 0.95, RMSEA < 0.05, and SRMR < 0.08.Citation71 Correlated error terms were freely estimated within each domain (generic beliefs, intermediate beliefs, and proximal beliefs). Mplus uses model modification indices to determine what parameters should be added to the model to improve model fit. Modification indices are chi-square statistics with one degree of freedom for the fixed and constrained parameters in a structural equation model. They estimate the change in the improvement in the likelihood-ratio chi-square statistic for the model if the corresponding parameter is respecified as a free parameter. Modifications that improve model fit are regarded as potential changes that can be made to the SEM model. The hypothesized relationships were tested based on their statistical significances of path coefficients.

Results

Survey noncontact

A 26.5% contact rate was achieved. Compared to those who were invited but did not respond to the survey, those successfully contacted were more likely to be age 55 and older, white, and college educated.Citation9

Sample characteristics

As shown in , the average age of respondents was 58 years (range = 40–90 years), and 65% were female and 89% were white. Forty-one percent had at least a four-year college education and just under half (45%) had an annual income of $50,000 or more. Hypertension and hyperlipidemia were each reported by about a quarter of respondents (24% and 23%, respectively). A smaller percentage of respondents had osteoporosis (17%), diabetes (15%), asthma (13%), or other CVD (8%). A majority of the samples rated their health as good (39.1%) or fair (28.8%).

Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics

Results of SEM

presents the standardized path coefficients from the SEM model for the proximal treatment beliefs. Goodness of fit indices showed good model fit with CFI = 0.973, RMSEA = 0.031 and SRMR = 0.032. The chi-square test was statistically significant (chi-square = 248, df = 121, P < 0.0001), reflecting a relatively good model fitCitation72 given the sample size and deviations from multivariate normality.Citation73–Citation75 The model fit was much improved compared to the baseline full model (chi-square = 299, df = 24, RMSEA = 0.104) and an alternative model without considering modifications (chi-square = 324, df = 109, RMSEA = 0.043).

Greater perceived need for medications was related to greater perceived disease severity (β = 0.480), less value placed on nutraceuticals (β = −0.249), more knowledge about the index medication (β = 0.244), greater patient engagement in their care (β = 0.137), more perceived immunity to side effects (β = 0.119), and less information seeking (β = −0.090). In addition, age was positively related to perceived need for medications. Compared to patients with hypertension, those with dyslipidemia, osteoporosis, or other CVD perceived less need for the index medication. Over two-thirds (68.3%) of the variation in perceived need for medications was explained by these eight significant predictors.

Fewer medication concerns were associated with more perceived immunity to side effects (β = 0.353), less value placed on nutraceuticals (β = −0.318), more knowledge about the index medication (β = 0.164), greater patient engagement in their care (β = 0.125), less information seeking (β = −0.084), less perceived disease severity (β = −0.078), and less of an internal locus of control (β = −0.051). As age increased, medication concerns decreased. Compared to patients with hypertension, those with dyslipidemia or osteoporosis had more medication concerns. One-half (50.9%) of the variation in perceived medication concerns was explained by these nine significant predictors.

Better medication affordability was related to less perceived disease severity (β = −0.233), greater income (β = 0.231), less value placed on nutraceuticals (β = −0.222), older age (β = 0.166), better self-rated health (β = 0.136), better mental health (β = 0.101), and more knowledge about the index medication (β = 0.082). Females found medications to be less affordable, while education was positively related to perceived medication affordability. One-third (34.0%) of the variation in perceived medication affordability was explained by these nine significant predictors.

The four intermediate beliefs were then modeled as dependent variables (). Greater perceived disease severity was related to worse self-rated health (β = −0.262), greater patient engagement in their care (β = 0.254), greater information seeking (b = 0.122), and worse mental health (b = −0.112). As education increased, perceptions of disease severity decreased. Compared to patients with hypertension, those with asthma or osteoporosis perceived their diseases to be less severe, while those with other CVD and diabetes perceived their conditions to be more severe. One-quarter (25.1%) of the variation in perceived disease severity was explained by these six significant predictors.

Table 3 Standardized path loadings of path model in predicting intermediate beliefs

Greater knowledge about the index medication was related to greater patient engagement in their care (β = 0.521), greater information-seeking tendencies (β = 0.325), more of an internal locus of control (β = 0.062), and better mental health (β = 0.047). Close to one-half (47.7%) of the variation in knowledge about the index medication was explained by these four predictors.

Greater perceived immunity to side effects was associated with greater patient engagement in their care (β = 0.259), less information-seeking tendencies (β = –0.242), and better mental health (β = 0.119). Men felt more immune to side effects. As education increased, perceived immunity to side effects increased. Fifteen percent of the variation in perceived immunity to side effects was explained by these five predictors.

More value placed on nutraceuticals was associated with less patient engagement in care (β = −0.415), a greater internal locus of control (β = 0.209), greater information-seeking tendencies (β = 0.126), and better self-rated health (β = 0.100). Younger persons, nonwhites, and respondents with osteoporosis or asthma placed greater value on nutraceuticals compared to those with hypertension. As both education and income increased, value placed on nutraceuticals decreased. Over one-quarter (28.6%) of the variation in perceived value of nutraceuticals was explained by these predictors.

Determinants of the more distal generic beliefs are presented in . The more distal generic beliefs were predominately influenced by age and disease. Older adults and respondents with asthma were more engaged in their care compared to responders with hypertension (R2 = 0.037). Greater information-seeking tendency was associated with female gender, more education, older age, and having asthma or other CVD compared to hypertension (R2 = 0.077). Internal locus of control was associated with less education and nonwhite race (R2 = 0.014). Better self-rated health was associated with higher income, older age, and a lower likelihood of other CVD or diabetes compared to hypertension (R2 = 0.121). Finally, better mental health was associated with older age and higher income (R2 = 0.107).

Discussion

Over the past 40 years, research on the determinants of medication adherence has gradually shifted from a focus on generic health beliefs to beliefs specific to a treatment and a disease. The Necessity-Concerns FrameworkCitation6 and Proximal–Distal ContinuumCitation9 are two frameworks that hold that medication adherence is more powerfully explained by treatment-specific than by generic beliefs. Generic beliefs, in turn, are useful in understanding the determinants of disease-specific beliefs. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study that has concurrently modeled the predictors of treatment-specific, proximal medication beliefs: perceived need for medications, perceived medication concerns, and perceived medication affordability.

Numerous hypotheses were tested in the SEM modeling of the proximal–distal continuum. However, only a few components of the proximal–distal continuum consistently emerged as statistically-significant predictors with relatively large path coefficients (perceived disease severity, patient knowledge, perceived side-effect immunity, perceived value of nutraceuticals, and patient engagement). These five variables are also the most clinically mutable beliefs and skills in the proximal–distal continuum. Because so few studies have studied the determinants of treatment-specific beliefs, we contextualize these results largely with past research on medication adherence and discuss their implications for adherence communication and adherence interventions.

Three of the intermediate, independent variables – perceived disease severity, knowledge about the index medication, and perceived value of nutraceuticals – were significantly associated with all three proximal adherence drivers. Perceived disease severity – or the potential for a condition to cause physical, mental or psychosocial harm – is a significant component of most social-cognitive models of medication taking.Citation2 Consistent with past research,Citation18–Citation21,Citation76,Citation77 perceived disease severity was a significant predictor of the three proximal treatment beliefs, but particularly of perceived need for medications. Patients who perceive their disease to be more severe may appreciate the long-term value of therapy, thus strengthening their intrinsic commitment to medication taking. Patients who perceive their disease to be more severe might be taking multiple medications, thereby making medications less affordable and raising concerns about medication side effects and medication interactions. Greater disease severity has been directly linked to improved medication adherence in numerous studiesCitation78–Citation82 including a meta-analysis.Citation83 Lack of perceived disease severity was cited as a reason for both medication nonfulfillment and nonpersistence in a study of US adults with chronic disease.Citation62 Patients need to understand the severity of their condition in order to internalize the rationale for therapy and develop ego commitment to the medication. Health care providers are uniquely qualified to convey to patients the potential severity of their conditions as well as short- and long-term consequences of undertreated or untreated chronic disease. Educational-based adherence interventions should explicitly address disease severity as a content area and assess patient understanding using well-established, patient-centered communication techniques.

In this study, patients with more knowledge about the index medication had significantly greater commitment to (need for) the medication, fewer medication concerns, and greater perceived medication affordability. The largest effect was observed for perceived need for the medication. Patient knowledge has been positively linked with medication adherence in many studies.Citation51,Citation84–Citation92 Information/knowledge is one of the troika of adherence drivers in two adherence conceptual frameworks – the Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills modelCitation7 and the Information-Motivation-Strategy model.Citation8 Lack of knowledge about the disease and/or prescribed therapy has been reported by patients as a reason for medication nonfulfillment or nonpersistence.Citation93–Citation96

Both qualitativeCitation97–Citation101 and quantitativeCitation102–Citation106 research has revealed that many patients lack knowledge about their diagnosed conditions, the potential severity of their conditions, and the consequences of lack of treatment. Patients also frequently report a lack of information about newly prescribed medications.Citation43,Citation102,Citation103,Citation107–Citation116 Without sufficient knowledge about their condition, its potential severity, and the rationale for the prescribed medication, many patients may find it difficult to identify with (be ego involved with) the diagnosis and therapy and to accept therapy with a sense of autonomous choice. When uncertainty and ambiguity are high, people tend to pessimistically evaluate the risk and benefits of therapy.Citation117 Thus, lack of information and knowledge about the diagnosed condition and the prescribed therapy can exacerbate patients’ uncertainty and ambivalence about prescription medications and can inhibit their internalization of their condition as chronic in nature.

Past educational/knowledge-based adherence interventions have tended to have small effect sizes.Citation118 This finding may be due to education and knowledge being operationalized and delivered differently across studies (eg, as disease knowledge, risk-factor knowledge, medication knowledge, and/or regimen knowledge) and the possibility that knowledge may more powerfully predict the proximal determinants of adherence –perceived need, concerns, and affordability – than adherence per se. Further, few adherence interventions have involved patients in the design and content of the intervention. Future adherence interventions should be truly patient-centered and involve patients a priori in determining what is needed, how much is needed, for how long, and via what channel. It is plausible that what newly diagnosed heart failure patients require in terms of information may be quantitatively and qualitatively different from what breast cancer patients newly prescribed adjuvant hormonal therapy need and prefer. Future adherence interventions should conceptualize knowledge in a multifactorial sense and deliver it longitudinally via a variety of channels and settings.Citation119

Many past knowledge-based adherence interventions have been of short duration with only a handful or less of interventional touch points. Future adherence interventions should focus on the first two months of therapy, when the risk of nonpersistence is greatest. Multiple interventional touch points can reinforce learning and help minimize uncertainty. Disease knowledge (etiology, severity, course, and sequelae) and medication knowledge (rationale, duration of therapy, alternative therapies, risks and benefits, and consequences of nonadherence) need to be communicated in health–literacy appropriate ways. Such knowledge could be delivered with patient-centered decision aids or tools that attempt to present unbiased and complete information about the potential benefits and downsides of treatment choices.Citation120 The promise of patient-centered decision aids for prescription medications lies in the hope that, through their use, providers will be preparing patients for treatment and involving them in the treatment process. Patients may more readily and consistently accept treatment if they feel the decision to start therapy is their choice rather than the provider’s directive.Citation121 Finally, it is important to underscore the difference between information/knowledge and patient understanding. Patients can only do what they understand.Citation8 Numerous patient-centered techniques are available to gauge patient understanding, such as “teach-back,”Citation122 “ask-tell-ask,”Citation123 and “elicit-provide-elicit.”Citation124 These techniques could not only be used in adherence interventions but in routine clinical practice as well at the time of prescribing. In one study, physicians trained in ask-tell-ask were able to successfully employ the technique without statistically increasing the median visit length.Citation125

A novel finding from this study is that respondents who placed more value on nutraceuticals (vitamins, supplements, and minerals) had lower perceived need for medications, more medication concerns, and less perceived medication affordability. Some adults believe over-the-counter and herbal remedies are less risky than prescription medications and that they are natural, safe, familiar, and can be used with less risk.Citation126–Citation128 GasconCitation100 found that there was greater confidence in herbal or natural remedies than in prescription medicines to treat hypertension. Other research has found use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) to be associated with suboptimal medication-effectiveness beliefsCitation129 and worse medication adherence.Citation130–Citation134 Favorable attitude toward CAM has been reported to be associated with worse adherence intentions.Citation135 Thus, some adults may be substituting pharmaceuticals with nutraceuticals.

An uncertainty lens helps to explain why some patients migrate toward nutraceuticals and alternative medicine for the self-management of chronic disease – they are viewed as doing something good for oneself (“natural” remedies) and as actions involving little risk and little threat to the status quo. Internet website and print communications abound with advertisements that claim to treat or cure chronic disease naturally. Past research has shown that providers are not proactive in discussing nutraceuticals and CAM,Citation131,Citation136 and that patients do not proactively disclose their nutraceutical and CAM use to their providers.Citation137,Citation138 Physicians, pharmacists, and interventionists should proactively address use of nutraceuticals with patients and communicate their relative clinical efficacy for the treatment of chronic disease compared to prescription medications. Future research should better understand the role of nutraceuticals specifically, and CAM generally, in patients’ adherence decisions.

Perceived side-effect immunity was a significant predictor of perceived need and perceived concerns but not affordability. Perceived side-effect immunity was the most important predictor of perceived medication concerns. Other research has linked perceived sensitivity to side effects with enhanced medication concerns.Citation6,Citation77 Fear of side effects and perceived side-effect susceptibility have been documented in the literature as reasons for medication nonadherence (nonfulfillment or nonpersistence)Citation62,Citation139–Citation145 and noncompliance (usage deviations).Citation146 Little is known about how or why patients come to feel susceptible to side effects. However, research has documented that patients report significant unmet need for side-effect information.Citation110,Citation147–Citation149 Physicians express concern that disclosure of side-effect information will increase patients’ report and/or experience of side effects through the effect of suggestability.Citation150–Citation154 However, extant research has refuted this line of reasoning: side-effect forewarning through verbal or written information has not been shown to increase reports of side effects.Citation155–Citation161 On the contrary, patients have relayed that, armed with information about side effects, they would be less likely to become alarmed should a side effect occur and would have fewer concerns about them.Citation162–Citation164 In one study, patients reported that detailed disclosure about side effects would make them feel more confident in the physician (94%), more likely to adhere to treatment (91%), and more confident in the medication (82%).Citation150

Unaddressed medication concerns and fear of side effects can intensify patients’ uncertainty especially when the potential benefits of medication therapy have not been appropriately communicated and when potential benefits do not occur immediately, as with most asymptomatic chronic conditions. Providers should disclose common side effects and create a plan with patients that addresses what they should do should a side effect occur.Citation165 Such collaborative communication behaviors are consistent with patient-centered care and shared decision making. Adherence interventionists can employ patient-centered decision aids to communicate both the pros and cons of treatment in a balanced manner.

Our measure of patient engagement assessed patient trust in their provider and patient involvement in their care. In this study, patient engagement was a significant predictor of six of the seven outcomes (all but perceived medication affordability). Patients who were more engaged in their care had a greater perceived need for medications, fewer medication concerns, perceived their disease to be more severe, had more knowledge about the index medication, felt more immune to side effects, and valued nutraceuticals less. The greatest impact was on prescription-medication knowledge. In women with osteoporosis, Schousboe et alCitation20 also found patient engagement to be significantly related to greater perceived need for medications and fewer medication concerns. Two other studies reported patient trust to be associated with better medication beliefs,Citation21,Citation166 a finding similar to our observed results. Both patient trustCitation167–Citation171 and patient involvementCitation172–Citation174 have been demonstrated in past research to be associated with improved medication adherence. Two recent meta-analyses concluded that better physician–patient collaborationCitation175 and better physician communicationCitation176 significantly influence medication adherence.

Patient engagement is a key foundational element of patient-centered care and shared decision making. Past research has shown that patients can be coached to be more proactively involved in their care.Citation177–Citation185 Involving patients in medication-therapy decision making may increase their intrinsic motivation and ego involvement in treatment. A simple way to engage patients is to ask whether they are ready to commit to therapy. Patients’ expression of uncertainty or ambivalence is a marker for unresolved concerns or unmet information needs. Patient-centered decision aids for prescription medications may be a cost- and time-effective way of increasing patient engagement in their treatment in both clinical practice and in adherence interventions.

Although numerous hypotheses were tested in the SEM modeling of the proximal–distal continuum, none of the observed results were anomalous. In the vast majority of findings, coefficient signs were in the expected direction. As a predictor variable, the multi-item scale assessing health-information seeking yielded three results that could have plausibly been either positive or negative. Patients with greater health–information seeking tendencies had less perceived need for medications (), more perceived medication concerns, (), and less perceived immunity to side effects (). While health-information seeking was significantly and positively related to greater patient knowledge (), it is possible that health-information seeking could generate negative or even conflicting information, which could then dampen perceived need, elevate medication concerns, and elevate susceptibility to side effects.

Study strengths and limitations

There are both strengths and limitations to the study. In terms of strengths, use of the proximal–distal continuum was based upon both conceptual and empirical learning accumulated over the past 40 years. A large, internet-based panel of adults with chronic disease was accessed with representation from 47 of the 50 US states. Most of the multi-item scales were highly internally consistent (range of Cronbach’s alpha of 0.76 to 0.97, median = 0.91). We had a large sample size (n = 1072) upon which to test the SEM model.

In terms of limitations, the survey contact rate (26.5%) was low. Survey noncontact analysis indicated that persons aged 55 years and older, whites, and those with at least a college degree were more likely to be successfully contacted than their respective counterparts.Citation9 The obtained internet-based sample was slightly underrepresented by adults with income less than $25,000 annually compared to the US adult population.Citation186 Also, relative to the US adult population aged 25 years and older,Citation187,Citation188 the obtained sample had an underrepresentation of adults with less than a high-school education, an overrepresentation of adults with at least a college degree, and overrepresentation of whites. Because of these demographic differences between the obtained sample and the US general adult population, generalizability of our results to the broader US population may not be appropriate. An Internet panel was used, which also may limit generalizability. The study was cross sectional. As a result of the cross-sectional design, no inferences regarding causality of the elements of the proximal–distal continuum can be made. The study involved adults with self-identified chronic disease. None of the six study conditions were substantiated with medical records. On the other hand, a well-defined, chronic disease panel was accessed and the six conditions were reverified using a separate, independent screener than was used to enroll the Chronic Illness Panel. Only six conditions were studied, although they are highly prevalent in the US adult population. No psychiatric conditions were studied. The array of adherence drivers tested in the proximal–distal continuum was not exhaustive of the 200 putative adherence determinants.Citation189 We did not study some adherence determinants included in other research, such as self-efficacy, social support, symptom severity, the experience of side effects, side-effect severity, length of time with the diagnosis, and length of time in treatment with prescription-medication therapy. We only tested the proximal–distal continuum and did not test alternative theoretical models of adherence drivers.

Conclusion

For decades now, nonadherence has been among the most significant problems facing medical practice.Citation190 Nonadherence is a psychosocial marker that issues important to patients were not addressed – that patients have unvoiced uncertainties and ambivalence about their condition and prescribed therapy. In clinical practice, a shroud of silence envelopes the topic of medication adherence: physicians often do not proactively ask about adherence and patients frequently do not tell them when they fail to fill a new prescription or stop therapy on their own.Citation9 Thus, patients are largely alone with their doubts and uncertainties. For long-term medication adherence, patients need to autonomously and intrinsically commit to therapy and this is more likely to occur when they are informed (about disease knowledge, disease severity, medication knowledge and rationale, consequences of nonadherence, and side effects), understand, and are motivated (engaged in their care, perceive a need for medication, and believe the benefits outweigh the risks). In short, intuitively patient-centered strategies are needed to help patients to know what their condition is, why the medication is needed, how the prescribed therapy may help, and how the benefits may outweigh the risks.

Testing the proximal–distal continuum of adherence drivers sheds light on specific areas where adherence dialogue and enhancement could focus. Our results can help to inform the design of future adherence interventions, as well as the content of patient-education materials and adherence reminder letters. An important learning from testing the proximal–distal continuum is that future adherence interventions need to move from manipulating single adherence barriers to interceding in a multidimensional space. Results also suggest that intervening along the etiological continuum of patient beliefs, states, and skills may more optimally improve adherence than intervening in a single causal space. Interventions that focus on distal beliefs, states, and skills should be deprioritized. Instead of assuming a one-size-fit-all design, future adherence interventions should target persons who are deficit in the proximal determinants of adherence: perceived need for medications, perceived medication concerns, and perceived medication affordability. In addition, it should be possible to target patients or tailor interventions using the most important sociomedical predictors identified in this study: perceived disease severity, patient knowledge, perceived side-effect immunity, perceived value of nutraceuticals, and patient engagement.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BrawleyLRCulos-ReedSNStudying adherence to therapeutic regimens: overview, theories, recommendationsControl Clin Trials200021Suppl 5S156S163

- BeckerMHMaimanLASociobehavioral determinants of compliance with health and medical care recommendationsMed Care197513110241089182

- FumazCRMunoz-MorenoJAMoltóJSustained antiretroviral treatment adherence in survivors of the pre-HAART era: attitudes and beliefsAIDS Care200820779680518728987

- FarmerAKinmonthALSuttonSMeasuring beliefs about taking hypoglycaemic medication among people with Type 2 diabetesDiabet Med200623326527016492209

- JohnsonSSDriskellMMJohnsonJLTranstheoretical model intervention for adherence to lipid-lowering drugsDis Manag20069210211416620196

- HorneRRepresentations of medications and treatment: advances in theory and measurementPetrieKJWeinmanJAPerceptions of Health and IllnessAmsterdamHarwood1997155188

- AmicoKRToro-AlfonsoJFisherJDAn empirical test of the information, motivation and behavioral skills model of antiretroviral therapy adherenceAIDS Care200517666167316036253

- DiMatteoMRHaskard-ZolnierekKBMartinLRImproving patient adherence: a three-factor model to guide practiceHealth Psychol Rev2012617491

- McHorneyCAThe Adherence Estimator: a brief, proximal screener for patient propensity to adhere to prescription medications for chronic diseaseCurr Med Res Opin200925121523819210154

- GardnerEMBurmanWJMaraviMEDavidsonAJSelective drug taking during combination antiretroviral therapy in an unselected clinic populationJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr200540329430016249703

- HoPMSpertusJAMasoudiFAImpact of medication therapy discontinuation on mortality after myocardial infarctionArch Intern Med2006166171842184717000940

- Lo ReV3rdTealVLocalioARAmorosaVKKaplanDEGrossRRelationship between adherence to hepatitis C virus therapy and virologic outcomes: a cohort studyAnn Intern Med2011155635336021930852

- KrigsmanKNilssonJLRingLAdherence to multiple drug therapies: refill adherence to concomitant use of diabetes and asthma/COPD medicationPharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf200716101120112817566142

- PietteJDHeislerMGanoczyDMcCarthyJFValensteinMDifferential medication adherence among patients with schizophrenia and comorbid diabetes and hypertensionPsychiatr Serv200758220721217287377

- AgarwalSTangSSRosenbergNDoes synchronizing initiation of therapy affect adherence to concomitant use of antihypertensive and lipid-lowering therapy?Am J Ther200916211912619114872

- BennerJSChapmanRHPetrillaAATangSSRosenbergNSchwartzJSAssociation between prescription burden and medication adherence in patients initiating antihypertensive and lipid-lowering therapyAm J Health Syst Pharm200966161471147719667004

- YoodRAMazorKMAndradeSEEmaniSChanWKahlerKHPatient decision to initiate therapy for osteoporosis: the influence of knowledge and beliefsJ Gen Intern Med200823111815182118787907

- HorneRWeinmanJSelf-regulation and self-management in asthma: exploring the role of illness perceptions and treatment beliefs in explaining non-adherence to preventer medicationPsychol Health20021711732

- NicklasLBDunbarMWildMAdherence to pharmacological treatment of non-malignant chronic pain: the role of illness perceptions and medication beliefsPsychol Health201025511520391203

- SchousboeJTDavisonMLDowdBThiede CallKJohnsonPKaneRLPredictors of patients’ perceived need for medication to prevent fractureMed Care201149327328021224740

- Baloush-KleinmanVLevineSZRoeDShnittDWeizmanAPoyurovskyMAdherence to antipsychotic drug treatment in early-episode schizophrenia: a six-month naturalistic follow-up studySchizophr Res20111301–317618121636254

- AckersonKPrestonSDA decision theory perspective on why women do or do not decide to have cancer screening: systematic reviewJ Adv Nurs20096561130114019374678

- OgginsJNotions of HIV and medication among multiethnic people living with HIVHealth Soc Work2003281536212621933

- DiMatteoMRVariations in patients’ adherence to medical recommendations: a quantitative review of 50 years of researchMed Care200442320020915076819

- TreharneGJLyonsACKitasGDMedication adherence in rheumatoid arthritis: effects of psychosocial factorsPsychol Health Med200493337349

- ByrneMWalshJMurphyAWSecondary prevention of coronary heart disease: patient beliefs and health-related behaviourJ Psychosom Res200558540341516026655

- GrunfeldEAHunterMSSikkaPMittalSAdherence beliefs among breast cancer patients taking tamoxifenPatient Educ Couns20055919710216198223

- SudAKline-RogersEMEagleKAAdherence to medications by patients after acute coronary syndromesAnn Pharmacother200539111792179716204391

- HorneRCooperVGellaitryGDateHLFisherMPatients’ perceptions of highly active antiretroviral therapy in relation to treatment uptake and adherence: the utility of the necessity-concerns frameworkJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr200745333434117514019

- GonzalezJSPenedoFJLlabreMMPhysical symptoms, beliefs about medications, negative mood, and long-term HIV medication adherenceAnn Behav Med2007341465517688396

- MoshkovskaTStoneMAClatworthyJAn investigation of medication adherence to 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy in patients with ulcerative colitis, using self-report and urinary drug excretion measurementsAliment Pharmacol Ther20093011–121118112719785623

- BucksRSHawkinsKSkinnerTCHornSSeddonPHorneRAdherence to treatment in adolescents with cystic fibrosis: the role of illness perceptions and treatment beliefsJ Pediatr Psychol200934889390219196850

- ClatworthyJBowskillRParhamRRankTScottJHorneRUnderstanding medication non-adherence in bipolar disorders using a Necessity-Concerns FrameworkJ Affect Disord20091161–2515519101038

- SchousboeJTDowdBEDavisonMLKaneRLAssociation of medication attitudes with non-persistence and non-compliance with medication to prevent fracturesOsteoporos Int201021111899190919967337

- GrivaKDavenportAHarrisonMNewmanSPNon-adherence to immunosupressive medications in kidney transplantation: intent vs forgetfulness and clinical markers of medication intakeAnn Behav Med2012441859322454221

- RupparTMDobbelsFDe GeestSMedication beliefs and antihypertensive adherence among older adults: a pilot studyGeriatr Nurs2012332899522387190

- SchoenthalerAMSchwartzBSWoodCStewartWFPatient and physician factors associated with adherence to diabetes medicationsDiabetes Educ201238339740822446035

- MaidmentRLivingstonGKatonaCJust keep taking the tablets: adherence to antidepressant treatment in older people in primary careInt J Geriatr Psychiatry200217875275712211126

- AyalonLAreánPAAlvidrezJAdherence to antidepressant medications in black and Latino elderly patientsAm J Geriatr Psychiatry200513757258016009733

- GellaitryGCooperVDavisCFisherMDateHLHorneRPatients’ perception of information about HAART: impact on treatment decisionsAIDS Care200517336737615832885

- CarrAJThompsonPWCooperCFactors associated with adherence and persistence to bisphosphonate therapy in osteoporosis: a cross-sectional surveyOsteoporos Int200617111638164416896510

- HunotVMHorneRLeeseMNChurchillRCA cohort study of adherence to antidepressants in primary care: the influence of antidepressant concerns and treatment preferencesPrim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry200792919917607330

- MannDMAllegranteJPNatarajanSHalmEACharlsonMPredictors of adherence to statins for primary preventionCardiovasc Drugs Ther200721431131617665294

- AikensJEPietteJDDiabetic patients’ medication underuse, illness outcomes, and beliefs about antihyperglycemic and antihypertensive treatmentsDiabetes Care2009321192418852334

- DaleboudtGMBroadbentEMcQueenFKapteinAAIntentional and unintentional treatment nonadherence in patients with systemic lupus erythematosusArthritis Care Res (Hoboken)201163334235021120967

- O’CarrollRWhittakerJHamiltonBJohnstonMSudlowCDennisMPredictors of adherence to secondary preventive medication in stroke patientsAnn Behav Med201141338339021193977

- SolomonDHBrookhartMATsaoPPredictors of very low adherence with medications for osteoporosis: towards development of a clinical prediction ruleOsteoporos Int20112261737174320878392

- PatelSCSpaethGLCompliance in patients prescribed eyedrops for glaucomaOphthalmic Surg19952632332367651690

- BrownCMSegalRThe effects of health and treatment perceptions on the use of prescribed medication and home remedies among African American and white American hypertensivesSoc Sci Med19964369039178888461

- GoemanDPAroniRAStewartKPatients’ views of the burden of asthma: a qualitative studyMed J Aust2002177629529912225275

- KamatariMKotoSOzawaNFactors affecting long-term compliance of osteoporotic patients with bisphosphonate treatment and QOL assessment in actual practice: alendronate and risedronateJ Bone Miner Metab200725530230917704995

- FriedmanDSHahnSRGelbLDoctor-patient communication, health-related beliefs, and adherence in glaucoma: results from the Glaucoma Adherence and Persistency StudyOphthalmology200811581320132718321582

- WuJRMoserDKChungMLLennieTAPredictors of medication adherence using a multidimensional adherence model in patients with heart failureJ Card Fail200814760361418722327

- KimEGuptaSBolgeSChenCCWhiteheadRBatesJAAdherence and outcomes associated with copayment burden in schizophrenia: a cross-sectional surveyJ Med Econ201013218519220235753

- MarshallIJWolfeCDMckevittCLay perspectives on hypertension and drug adherence: systematic review of qualitative researchBMJ2012345e395322777025

- National Center for Health StatisticsHealth, United States, 2010: With Special Feature on Death and DyingHyattsvilleUS Department of Health and Human Services2011

- DeVolRBedroussianACharuwornAAn Unhealthy America: The Economic Burden of Chronic Disease – Charting a New Course to Save Lives and Increase Productivity and Economic GrowthSanta MonicaThe Milken Institute2007

- The American Association for Public Opinion ResearchStandard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for SurveysLenexaAAPOR2008

- WallstonKAMultidimensional health locus of control (MHLC) scales [updated June 15, 2007]. Available from: http://www.vanderbilt.edu/nursing/kwallston/mhlcscales.htmAccessed January 15, 2008

- WareJESherbourneCDThe MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selectionMed Care19923064734831593914

- McHorneyCAGadkariASIndividual patients hold different beliefs to prescription medications to which they persist vs nonpersist and persist vs nonfulfillPatient Prefer Adherence2010418719520694180

- McHorneyCASpainCVFrequency of and reasons for medication non-fulfillment and non-persistence among American adults with chronic disease in 2008Health Expect201114330732020860775

- PietteJDBeardARoslandAMMcHorneyCABeliefs that influence cost-related medication non-adherence among the “haves” and “have nots” with chronic diseasesPatient Prefer Adherence2011538939621949602

- GadkariASMcHorneyCAUnintentional non-adherence to chronic prescription medications: how unintentional is it really?BMC Health Serv Res2012Epub June14

- LikertRA technique for the measurement of attitudesArch Psychol1932140555

- WrightSCorrelation and causationJ Agric Res192120557585

- WrightSThe method of path coefficientsAnn Math Stat19345161215

- WrightSPath coefficients and path regressions: alternative or complementary conceptsBiometrics196016189202

- BollenKAStructural Equations with Latent VariablesNew YorkWiley & Sons1989

- MuthünLMüthenBMplus User’s Guide6th edLos AngelesMuthen & Muthen1998–2007

- HuLBentlerPMCutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternativesStructural Equation Modeling19996155

- KlineRPrinciples and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling3rd edNew YorkGuilford2010

- BentlerPMBonettDGSignificance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structuresPsychol Bulletin198088588606

- JöreskogKSörbomDLISREL 8: User’s Reference GuideChicagoScientific Software Int1996

- McIntoshCRethinking fit assessment in structural equation modelling: A commentary and elaboration on BarrettPers Individ Dif200742859867

- AikensJENeaseDEJrKlinkmanMSExplaining patients’ beliefs about the necessity and harmfulness of antidepressantsAnn Fam Med200861232918195311

- HorneRParhamRDriscollRRobinsonAPatients’ attitudes to medicines and adherence to maintenance treatment in inflammatory bowel diseaseInflamm Bowel Dis200915683784419107771

- SireyJABruceMLAlexopoulosGSPerlickDAFriedmanSJMeyersBSStigma as a barrier to recovery: Perceived stigma and patient-rated severity of illness as predictors of antidepressant drug adherencePsychiatr Serv200152121615162011726752

- De SmetBDEricksonSRKirkingDMSelf-reported adherence in patients with asthmaAnn Pharmacother200640341442016507619

- BardelAWallanderMASvärdsuddKFactors associated with adherence to drug therapy: a population-based studyEur J Clin Pharmacol200763330731417211620

- BolmanCArwertTGVöllinkTAdherence to prophylactic asthma medication: habit strength and cognitionsHeart Lung2011401637520561874

- UnniEFarrisKBDeterminants of different types of medication non-adherence in cholesterol lowering and asthma maintenance medications: a theoretical approachPatient Educ Couns201183338239021454030

- DiMatteoMRHaskardKBWilliamsSLHealth beliefs, disease severity, and patient adherence: a meta-analysisMed Care200745652152817515779

- VillerFGuilleminFBrianconSMoumTSuurmeijerTvan den HeuvelWCompliance to drug treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a 3 year longitudinal studyJ Rheumatol199926102114212210529126

- KimEYHanHRJeongSDoes knowledge matter? Intentional medication nonadherence among middle-aged Korean Americans with high blood pressureJ Cardiovasc Nurs200722539740417724422

- RingeJDChristodoulakosGEMellströmDPatient compliance with alendronate, risedronate and raloxifene for the treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal womenCurr Med Res Opin200723112677268717883882

- MoriskyDEAngAKrousel-WoodMWardHJPredictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient settingJ Clin Hypertens (Greenwich)200810534835418453793

- WellsKPladevallMPetersonELRace-ethnic differences in factors associated with inhaled steroid adherence among adults with asthmaAm J Respir Crit Care Med2008178121194120118849496

- BermejoFLópez-San RománAAlgabaAFactors that modify therapy adherence in patients with inflammatory bowel diseaseJ Crohns Colitis20104442242621122538

- SonYJKimHGKimEHChoiSLeeSKApplication of support vector machine for prediction of medication adherence in heart failure patientsHealthc Inform Res201016425325921818444

- Al-QazazHKSulaimanSAHassaliMADiabetes knowledge, medication adherence and glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetesInt J Clin Pharm20113361028103522083724

- BowryADShrankWHLeeJLStedmanMChoudhryNKA systematic review of adherence to cardiovascular medications in resource-limited settingsJ Gen Intern Med201126121479149121858602

- ParashosIAXiromeritisKZoumbouVStamouliSTheodotouRThe problem of non-compliance in schizophrenia: opinions of patients and their relatives. A pilot studyInt J Psychiatry Clin Pract200042147150

- MansurAPMattarAPTsuboCESimãoDTYoshiFRDaciKPrescription and adherence to statins of patients with coronary artery disease and hypercholesterolemiaArq Bras Cardiol200176211111811270314

- KripalaniSHendersonLEJacobsonTAVaccarinoVMedication use among inner-city patients after hospital discharge: patient-reported barriers and solutionsMayo Clin Proc200883552953518452681

- SajatovicMLevinJFuentes-CasianoECassidyKATatsuokaCJenkinsJHIllness experience and reasons for nonadherence among individuals with bipolar disorder who are poorly adherent with medicationCompr Psychiatry201152328028721497222

- TolmieEPLindsayGMKerrSMBrownMRFordIGawAPatients’ perspectives on statin therapy for treatment of hypercholesterolaemia: a qualitative studyEur J Cardiovasc Nurs20032214114914622639

- BajramovicJEmmertonLTettSEPerceptions around concordance – focus groups and semi-structured interviews conducted with consumers, pharmacists and general practitionersHealth Expect20047322123415327461

- BolliniPTibaldiGTestaCMunizzaCUnderstanding treatment adherence in affective disorders: a qualitative studyJ Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs200411666867415544664

- GascónJJSánchez-OrtunoMLlorBSkidmoreDSaturnoPJfor Treatment Compliance in Hypertension Study GroupWhy hypertensive patients do not comply with the treatment: results from a qualitative studyFam Pract200421212513015020377

- MorecroftCCantrillJTullyMPPatients’ evaluation of the appropriateness of their hypertension management--a qualitative studyRes Social Adm Pharm20062218621117138508

- BarberNParsonsJCliffordSDarracottRHorneRPatients’ problems with new medication for chronic conditionsQual Saf Health Care200413317217515175485

- NeameRHammondADeightonCNeed for information and for involvement in decision making among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a questionnaire surveyArthritis Rheum200553224925515818715

- MochariHFerrisAAdigopulaSHenryGMoscaLCardiovascular disease knowledge, medication adherence, and barriers to preventive action in a minority populationPrev Cardiol200710419019517917515

- ShiriCSrinivasSCFutterWTRadloffSEThe role of insight into and beliefs about medicines of hypertensive patientsCardiovasc J Afr200718635335718092108

- HobbsFDErhardtLRRycroftCfor From the Heart study InvestigatorsThe From The Heart study: a global survey of patient understanding of cholesterol management and cardiovascular risk, and physician-patient communicationCurr Med Res Opin20082451267127818355420

- RidoutSWatersWEGeorgeCFKnowledge of and attitudes to medicines in the Southampton communityBr J Clin Pharmacol19862167017123741718

- EnlundHVainioKWalleniusSPostonJWAdverse drug effects and the need for drug informationMed Care19912965585642046409

- McCormackPMLawlorRDoneganCKnowledge and attitudes to prescribed drugs in young and elderly patientsIr Med J199790129309230561

- MorrisLATabakERGondekKCounseling patients about prescribed medication: 12-year trendsMed Care1997351099610079338526

- BaratIAndreasenFDamsgaardEMDrug therapy in the elderly: what doctors believe and patients actually doBr J Clin Pharmacol200151661562211422022

- SleathBWurstKPatient receipt of, and preferences for receiving, antidepressant informationInt J Pharm Pract2002104235241

- CoulterAWhat do patients and the public want from primary care?BMJ200533175261199120116293845

- GrayRRofailDAllenJNeweyTA survey of patient satisfaction with and subjective experiences of treatment with antipsychotic medicationJ Adv Nurs2005521313716149978

- PatonCEsopRPatients’ perceptions of their involvement in decision making about antipsychotic drug choice as outlined in the NICE guidance on the use of atypical antipsychotics in schizophreniaJ Ment Health2005143305310

- RichardCLussierMTNature and frequency of exchanges on medications during primary care encountersPatient Educ Couns2006641–320721616781108

- HanPKKobrinSCKleinWMDavisWWStefanekMTaplinSHPerceived ambiguity about screening mammography recommendations: association with future mammography uptake and perceptionsCancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev200716345846617372241

- PetersonAMTakiyaLFinleyRMeta-analysis of trials of interventions to improve medication adherenceAm J Health Syst Pharm200360765766512701547

- BrownMTBussellJKMedication adherence: WHO cares?Mayo Clin Proc201186430431421389250

- WilsonSRStrubPBuistASShared treatment decision making improves adherence and outcomes in poorly controlled asthmaAm J Respir Crit Care Med2010181656657720019345

- StalmeierPFAdherence and decision AIDs: a model and a narrative reviewMed Decis Making201131112112920519453

- OatesDJPaasche-OrlowMKHealth literacy: communication strategies to improve patient comprehension of cardiovascular healthCirculation200911971049105119237675

- HahnSRPatient-centered communication to assess and enhance patient adherence to glaucoma medicationOphthalmology2009116Suppl 11S37S4219837259

- GabbayRADurdockKStrategies to increase adherence through diabetes technologyJ Diabetes Sci Technol20104366166520513334

- HahnSRLiptonRBSheftellFDHealthcare provider-patient communication and migraine assessment: results of the American Migraine Communication Study, phase IICurr Med Res Opin20082461711171818471346

- MorganMThe significance of ethnicity for health promotion: patients use of antihypertensive drugs in inner LondonInt J Epidemiol199524Suppl 1S79S847558558

- BissellPWardPRNoycePRThe dependent consumer: reflections on accounts of the risks of non-prescription medicinesHealth (London)200151530

- LynchNBerryDDifferences in perceived risks and benefits of herbal, over-the-counter conventional, and prescribed conventional, medicines, and the implications of this for the safe and effective use of herbal productsComplement Ther Med2007152849117544858

- JarmanCNPerronBEKilbourneAMTehCFPerceived treatment effectiveness, medication compliance, and complementary and alternative medicine use among veterans with bipolar disorderJ Altern Complement Med201016325125520192909

- Owen-SmithADiclementeRWingoodGComplementary and alternative medicine use decreases adherence to HAART in HIV-positive womenAIDS Care200719558959317505918

- GoharFGreenfieldSMBeeversDGLipGYJollyKSelf-care and adherence to medication: a survey in the hypertension outpatient clinicBMC Complement Altern Med20088418261219

- Krousel-WoodMAMuntnerPJoyceCJAdverse effects of complementary and alternative medicine on antihypertensive medication adherence: findings from the cohort study of medication adherence among older adultsJ Am Geriatr Soc2010581546120122040

- RoyALurslurchachaiLHalmEALiXMLeventhalHWisniveskyJPUse of herbal remedies and adherence to inhaled corticosteroids among inner-city asthmatic patientsAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol2010104213213820306816

- DeanAJWraggJDraperJMcDermottBMPredictors of medication adherence in children receiving psychotropic medicationJ Paediatr Child Health201147635035521309880

- VillagranMHajekCZhaoXPetersonEWittenberg-LylesECommunication and culture: predictors of treatment adherence among Mexican immigrant patientsJ Health Psychol201217344345221900335

- BrownCMPenaAResendizKPharmacists’ actions when patients use complementary and alternative medicine with medications: a look at Texas-Mexico border citiesJ Am Pharm Assoc (2003)201151561962221896460

- ChongCADiaz-GranadosNHawkerGAJamalSJosseRGCheungAMComplementary and alternative medicine use by osteoporosis clinic patientsOsteoporos Int200718111547155617603742

- MakJCFauxSUse of complementary and alternative medicine by patients with osteoporosis in AustraliaMed J Aust20101921545520047554

- LeungTNHainesCJChungTKFive-year compliance with hormone replacement therapy in postmenopausal Chinese women in Hong KongMaturitas200139319520111574178

- SonHParkKKimSWPaickJSReasons for discontinuation of sildenafil citrate after successful restoration of erectile functionAsian J Androl20046211712015154085

- BrownKKRehmusWEKimballABDetermining the relative importance of patient motivations for nonadherence to topical corticosteroid therapy in psoriasisJ Am Acad Dermatol200655460761317010739

- UlrikCSBackerVSøes-PetersenULangePHarvingHPlaschkePPThe patient’s perspective: adherence or non-adherence to asthma controller therapy?J Asthma200643970170417092852

- van GeffenECvan HultenRBouvyMLEgbertsACHeerdinkERCharacteristics and reasons associated with nonacceptance of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitor treatmentAnn Pharmacother200842221822518094342

- HarrisonTPrimary non-adherence to statin therapy in an integrated delivery system: patients’ perspectiveClin Med Res201193–4150151

- LakatosPLCzeglediZDavidGAssociation of adherence to therapy and complementary and alternative medicine use with demographic factors and disease phenotype in patients with inflammatory bowel diseaseJ Crohns Colitis20104328329021122517

- BustonKMWoodSFNon-compliance amongst adolescents with asthma: listening to what they tell us about self-managementFam Pract200017213413810758075

- MorrisLAA survey of patients’ receipt of prescription drug informationMed Care19822065966057109742

- GallupGJrCotugnoHEPreferences and practices of Americans and their physicians in antihypertensive therapyAm J Med1986816C20242879454

- DavisKSchoenCSchoenbaumSCMirror on the Wall: An Update on the Quality of American Health Care Through the Patient’s LensNew YorkThe Commonwealth Fund2006 Available from: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Publications/Fund-Reports/2006/Apr/Mirror-Mirror-on-the-Wall-An-Update-on-the-Quality-of-American-Health-Care-Through-the-Patients-Le.aspxAccessed September 14, 2012

- FadenRRBeckerCLewisCFreemanJFadenAIDisclosure of information to patients in medical careMed Care19811977187337266120

- StevensonFAThe strategies used by general practitioners when providing information about medicinesPatient Educ Couns20014319710411311843

- NairKDolovichLCasselsAWhat patients want to know about their medications. Focus group study of patient and clinician perspectivesCan Fam Physician20024810411011852597

- XuFInforming patients about drug effects using positive suggestionJ Manag Care Pharm200814439539618500917

- TarnDMPaternitiDAWilliamsBRCipriCSWengerNSWhich providers should communicate which critical information about a new medication? Patient, pharmacist, and physician perspectivesJ Am Geriatr Soc200957346246919175439

- MyersEDCalvertEJThe effect of forewarning on the occurrence of side-effects and discontinuance of medication in patients on amitriptylineBr J Psychiatry19731225694614644718283

- MyersEDCalvertEJThe effect of forewarning on the occurrence of side-effects and discontinuance of medication in patients on dothiepinJ Int Med Res1976442372401026548

- MyersEDCalvertEJInformation, compliance and side-effects: a study of patients on antidepressant medicationBr J Clin Pharmacol198417121256691885

- GibbsSWatersWEGeorgeCFPrescription information leaflets: a national surveyJ R Soc Med19908352922972380943

- HowlandJSBakerMGPoeTDoes patient education cause side effects? A controlled trialJ Fam Pract199031162642193996

- QuaidKAFadenRRViningEPFreemanJMInformed consent for a prescription drug: impact of disclosed information on patient understanding and medical outcomesPatient Educ Couns199015324925911659330

- LambGCGreenSSHeronJCan physicians warn patients of potential side effects without fear of causing those side effects?Arch Intern Med199415423275327567993161

- BakerDRobertsDENewcombeRGFoxKAEvaluation of drug information for cardiology patientsBr J Clin Pharmacol19913155255311888619

- GandhiTKBurstinHRCookEFDrug complications in outpatientsJ Gen Intern Med200015314915410718894

- HappellBManiasERoperCWanting to be heard: mental health consumers’ experiences of information about medicationInt J Ment Health Nurs200413424224815660592

- CoulterAPartnerships with patients: the pros and cons of shared clinical decision-makingJ Health Serv Res Policy19972211212110180362

- ThrasherADEarpJAGolinCEZimmerCRDiscrimination, distrust, and racial/ethnic disparities in antiretroviral therapy adherence among a national sample of HIV-infected patientsJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr2008491849318667919

- KerseNBuetowSMainousAG3rdYoungGCosterGArrollBPhysician-patient relationship and medication compliance: a primary care investigationAnn Fam Med20042545546115506581

- SchneiderJKaplanSHGreenfieldSLiWWilsonIBBetter physician-patient relationships are associated with higher reported adherence to antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV infectionJ Gen Intern Med200419111096110315566438

- PietteJDHeislerMKreinSKerrEAThe role of patient-physician trust in moderating medication nonadherence due to cost pressuresArch Intern Med2005165151749175516087823

- McGinnisBOlsonKLMagidDFactors related to adherence to statin therapyAnn Pharmacother200741111805181117925498

- NguyenGCLaVeistTAHarrisMLDattaLWBaylessTMBrantSRPatient trust-in-physician and race are predictors of adherence to medical management in inflammatory bowel diseaseInflamm Bowel Dis20091581233123919177509

- RenXSKazisLELeeAZhangHMillerDRIdentifying patient and physician characteristics that affect compliance with antihypertensive medicationsJ Clin Pharm Ther2002271475611846861

- LohALeonhartRWillsCESimonDHarterMThe impact of patient participation on adherence and clinical outcome in primary care of depressionPatient Educ Couns2007651697817141112

- KahnKLSchneiderECMalinJLAdamsJLEpsteinAMPatient centered experiences in breast cancer: predicting long-term adherence to tamoxifen useMed Care200745543143917446829

- ArbuthnottASharpeDThe effect of physician-patient collaboration on patient adherence in non-psychiatric medicinePatient Educ Couns2009771606719395222

- ZolnierekKBDimatteoMRPhysician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysisMed Care200947882683419584762

- GreenfieldSKaplanSWareJEJrExpanding patient involvement in care: Effects on patient outcomesAnn Intern Med198510245205283977198

- GreenfieldSKaplanSHWareJEJrYanoEMFrankHJPatients’ participation in medical care: effects on blood sugar control and quality of life in diabetesJ Gen Intern Med1988354484573049968

- O’ConnorAMRostomAFisetVDecision aids for patients facing health treatment or screening decisions: systematic reviewBMJ1999319721273173410487995

- ButowPDevineRBoyerMPendleburySJacksonMTattersallMHCancer consultation preparation package: changing patients but not physicians is not enoughJ Clin Oncol200422214401440915514382

- GriffinSJKinmonthALVeltmanMWGillardSGrantJStewartMEffect on health-related outcomes of interventions to alter the interaction between patients and practitioners: a systematic review of trialsAnn Fam Med20042659560815576546

- WilliamsGCMcGregorHZeldmanAFreedmanZRDeciELElderDPromoting glycemic control through diabetes self-management: evaluating a patient activation interventionPatient Educ Couns2005561283415590220

- LohASimonDWillsCEKristonLNieblingWHärterMThe effects of a shared decision-making intervention in primary care of depression: a cluster-randomized controlled trialPatient Educ Couns200767332433217509808

- MullanRJMontoriVMShahNDThe diabetes mellitus medication choice decision aid: a randomized trialArch Intern Med2009169171560156819786674

- ParchmanMLZeberJEPalmerRFParticipatory decision making, patient activation, medication adherence, and intermediate clinical outcomes in type 2 diabetes: a STARNet studyAnn Fam Med20108541041720843882

- US Census BureauIncome in the past 12 months2006FactFinder Available from: http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/STTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=01000US&-qr_name=ACS_2006_EST_G00_S1901&-ds_name=ACS_2006_EST_G00_&-redoLog=falseAccessed July 3, 2008

- US Census BureauEducational attainment2006FactFinder Available from: http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/STTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=01000US&-qr_name=ACS_2006_EST_G00_S1501&-ds_name=ACS_2006_EST_G00Accessed July 3, 2008

- GriecoEMCassidyRCOverview of race and hispanic origin 2000US Census Bureau2001 Available from: http://www.census.gov/prod/2001pubs/c2kbr01-1.pdfAccessed July 3, 2008

- CliffordSBarberNHorneRUnderstanding different beliefs held by adherers, unintentional nonadherers, and intentional nonadherers: application of the Necessity-Concerns FrameworkJ Psychosom Res2008641414618157998

- ErakerSAKirschtJPBeckerMHUnderstanding and improving patient complianceAnn Intern Med198410022582686362512