Abstract

Depression is one of the most common conditions to emerge after traumatic brain injury (TBI), and despite its potentially serious consequences it remains undertreated. Treatment for post-traumatic depression (PTD) is complicated due to the multifactorial etiology of PTD, ranging from biological pathways to psychosocial adjustment. Identifying the unique, personalized factors contributing to the development of PTD could improve long-term treatment and management for individuals with TBI. The purpose of this narrative literature review was to summarize the prevalence and impact of PTD among those with moderate to severe TBI and to discuss current challenges in its management. Overall, PTD has an estimated point prevalence of 30%, with 50% of individuals with moderate to severe TBI experiencing an episode of PTD in the first year after injury alone. PTD has significant implications for health, leading to more hospitalizations and greater caregiver burden, for participation, reducing rates of return to work and affecting social relationships, and for quality of life. PTD may develop directly or indirectly as a result of biological changes after injury, most notably post-injury inflammation, or through psychological and psychosocial factors, including pre injury personal characteristics and post-injury adjustment to disability. Current evidence for effective treatments is limited, although the strongest evidence supports antidepressants and cognitive behavioral interventions. More personalized approaches to treatment and further research into unique therapy combinations may improve the management of PTD and improve the health, functioning, and quality of life for individuals with TBI.

Introduction

Psychiatric disorders, including mood, anxiety, and substance-use disorders, are prevalent after traumatic brain injury (TBI), particularly when the injury is moderate to severe, and can have serious consequences for health, participation, and quality of life. Depression is the most common psychiatric condition to occur post-TBI, although comorbidity rates with other psychiatric and behavioral disorders are high.Citation1,Citation2 Despite the potentially serious consequences of depression, the majority of adults with TBI who experienced depression in the first year post-TBI did not receive treatment.Citation3 Treatment for post-traumatic depression (PTD) is complicated, however, due to its uncertain and multifactorial etiology; that is, it can develop through multiple and multifaceted pathways that may or may not directly result from the primary brain injury.Citation4 Therefore, treatment development for depression must occur in well-defined subgroups having similar symptom clusters or risk factors to address the unique underlying risk factors (eg, neurobiological changes and major life stressors) and tailor treatment accordingly.Citation4 This multifactorial nature of PTD could at least partially explain why response to PTD treatment is often poor compared to the broader major depressive disorder (MDD) population and why PTD treatment studies yield such variable results. This narrative review presents the following: 1) an updated overview of the prevalence and symptom presentation of PTD after moderate to severe TBI; 2) the impact of PTD on other long-term outcomes after moderate to severe TBI; 3) an overview of the various underlying conditions and etiological elements – from neurobiology to life stressors – that contribute to depression post-TBI; and 4) a summary of the successes and challenges in clinical management of PTD.

Methods

For this narrative review,Citation5 defined as a well-structured synthesis of available evidence that conveys a clear message supported by existing data,Citation6 we selected articles through a multistep process. The first author (SBJ) has a web-based literature database that has been continuously updated from 2013 to late 2016 and reflects the author’s research areas of interest, including TBI and depression. Articles included in this database were identified from several sources, including multiple PubMed searches (with weekly updates emailed to and reviewed by the first author to build the database), reference lists of relevant articles, database searches for other TBI-related publications and projects, and recommendations from other experts and collaborators. PubMed searches included the search term “brain injury” AND (alone and in combination): depression, affect, suicide, anxiety, fatigue, cytokine, biomarker, participation, treatment, systematic review. Within this database, we entered “depression” as a search term and reviewed abstracts of all resulting articles for relevance to TBI and depression and categorized articles into one or more of the following headings based on the relevant content: PTD symptoms and prevalence, PTD predictors, PTD impact, PTD treatment, mild TBI, and suicide. Articles published prior to 2000 or not published in English were excluded. Articles were then read to produce overall narrative summaries within each of the identified headings in the “Discussion” section, with priority given to previously published systematic reviews.

Discussion

Prevalence and symptom presentation

Numerous studies have reported prevalence for psychiatric disorders, and specifically, for depression after TBI. Psychiatric diagnoses, including mood, anxiety, and substance abuse disorders, were reported in 75.2% of individuals across the first 5 years post-TBI, with the majority of these (77.7%) emerging in the first year,Citation7 similar to another study indicating clinically significant psychiatric symptoms in 42% of adults with TBI at 6 months post-injury.Citation8 The majority of all psychiatric disorders (56.5%) post-TBI, and two-thirds of PTD diagnoses specifically,Citation9 were first-time diagnoses. Point prevalence rates of psychiatric disorders up to 20 years post-TBI ranged from 17% to 31%,Citation2,Citation10–Citation14 with a systematic review from 2011 estimating a point prevalence of 30% across multiple time points post moderate to severe TBI.Citation15 Cumulative prevalence rates for PTD were higher, just over 50%,Citation3,Citation9,Citation16 indicating that more than half of individuals with TBI will experience a depressive episode after injury. Most individuals will experience their first post-injury major depressive episode within the first year after TBI.Citation3 In addition, individuals with TBI had an elevated risk of suicide attempt (5-fold increase in risk) and completion (3–4 times more likely to die from suicide) compared to the general population.Citation17–Citation19

Depression and TBI share many common somatic symptoms, including fatigue, poor concentration, and sleep disruption. However, a study by Jorge et alCitation20 found that nearly all of the 66 adults with TBI in their cohort with notable depressive symptoms had depressed mood; that is, they found no evidence for “masked” depression. However, they did suggest that the symptoms that best differentiated those with and without depression also differed based on time post-injury, with symptoms related to sleep disruption and poor concentration only distinguishing between groups after 6 months post-injury. Seel et alCitation12 reported that the most common symptoms of depression across the first 10 years post-TBI included fatigue, distractibility, and rumination, and that rumination, self-criticism, and guilt were the symptoms that best differentiated those with depression from those without depression after TBI.Citation21 Furthermore, they found that depression post-TBI was characterized more by irritability, anger, and aggression than by sadness or tearfulness.Citation21

The impact of depression after TBI

PTD has implications for: 1) health, including higher re-hospitalization rates, greater suicide risk, and more caregiver burden; 2) participation, including return to work or school and social relationships; and 3) quality of life, including life satisfaction and overall well-being. Emotional changes, in particular, influenced long-term functional, psychosocial, and quality of life, especially as time since injury increased.Citation2,Citation3,Citation22–Citation28 Psychiatric conditions, such as depression, accounted for a majority of all re-hospitalizations beyond the first year post-injury,Citation29,Citation30 resulting in increased medical costs, and depression was among the strongest contributors to the high suicide risk reported after TBI.Citation19,Citation31 Depression was also significantly associated with poor vocational,Citation32,Citation33 psychosocial,Citation2,Citation32 and functional independence outcomes.Citation32,Citation34 A systematic review conducted by Garrelfs et alCitation33 reported a strong negative association between depression and return to work after acquired brain injury. Furthermore, depression was associated with poorer social functioning after TBI.Citation2,Citation25 One potential pathway through which depression could lead to poor participation outcomes is through disrupted behavior, such as aggression, impulsivity, or poor decision making. Post-TBI depression was highly associated with disrupted behavior after TBI,Citation2,Citation35 with some evidence indicating that depression preceded behavioral disruption,Citation36,Citation37 and disrupted behavior was a significant predictor of poor participation outcomes.Citation38 Often, however, it is difficult to differentiate cause from effect with regard to the relationship between PTD and other TBI-related impairments (Unpublished Material. Kumar RG, Gao S, Juengst S, Wagner AK, Fabio A. Post-traumatic depression effects on cognitive and physical impairments after moderate to severe civilian traumatic brian injury: a thematic review). For example, Perrin et alCitation39 found that functional independence may be more of a cause than a consequence of PTD, though they concluded that there was likely reciprocal causation between the two. Other predictors of PTD are discussed in the “Predictors/etiology of depression” section. Finally, PTD up to and beyond 10 years post-injury was associated with lower and declining life satisfactionCitation40–Citation42 and with poorer quality of life after TBI.Citation3,Citation25,Citation43–Citation45 A study by Diaz et alCitation45 reported that those with depression after TBI had greater impairments in all domains of the Short Form Health Survey (SF-36), a health-related quality of life measure, compared to those without depression.

Predictors/etiology of depression

The presentation of PTD is a multifactorial response to a number of underlying factors associated with TBI rather than just the direct result of a primary pathology.Citation4 Therefore, one of the greatest challenges to managing PTD is identifying its unique etiology, which can differ from person to person. Strakowski et alCitation4 emphasized the importance of identifying underlying risk factors for PTD that should be managed first, prior to addressing depressive symptoms, to maximize the chances for a positive treatment response; this included employing focused treatments in well-defined subgroups. As an example, one subgroup may be those who experience fatigue after TBI. Recent evidence suggests that fatigue is directly caused by TBI and may lead to, rather than result from, PTD.Citation46 Therefore, a treatment approach to PTD among those with primary fatigue may include addressing fatigue first. The first step toward personalized treatment approaches to PTD is to understand the heterogeneity in its risk factors and its underlying causes after TBI.

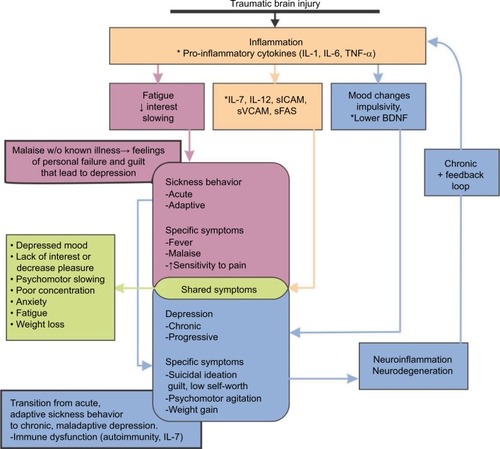

Biological mechanisms of PTD: inflammatory- induced depression

There are numerous biological mechanisms through which depression can develop after TBI,Citation47 including through inflammation (). Inflammatory mediators, including cytokines and inflammatory cell surface markers, are elevated with central nervous system (CNS) injury,Citation48,Citation49 including TBI,Citation50,Citation51 and these markers have been linked to depression in neurologically intact adults,Citation52–Citation54 older adults,Citation55 and individuals with chronic conditions associated with inflammation,Citation56–Citation61 including TBI.Citation62,Citation63 Acute cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) inflammation has been shown to be associated with PTD in the first year post-TBI.Citation62 Specifically, higher acute CSF levels of the cell surface markers such as sVCAM-1, sICAM-1, and sFAS were associated with a significant increase in risk for depression 6 months post-TBI, and higher acute CSF levels of IL-12 were associated with PTD at 12 months.Citation62 These markers are known to be associated with inflammation and white matter changes among older adults with depression.Citation55,Citation64 Inflammation occurring early after TBI may contribute to long-term, chronic inflammation even several years post-injury,Citation65 and hence, to chronic risk for depression.

Figure 1 Conceptual diagram of inflammatory-induced PTD.

Abbreviations: PTD, post-traumatic depression; TBI, traumatic brain injury

Acute inflammation post-TBI may also lead to depression via maladaptive “sickness behavior” (), which shares several symptoms (eg, lack of energy and interest and decreased appetite) with depression.Citation61,Citation66–Citation68 While sickness behavior is initially adaptive and helps the body respond to acute injury and/or infection, it becomes maladaptive if it persists for longer than 3–6 weeks.Citation61,Citation69 This time frame marks a transition from acute, adaptive behavior to a chronic, maladaptive process that may develop into depression.Citation70,Citation71 Cytokines such as IL-6 or tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) are signaling molecules of the immune system that have been associated with MDD.Citation67,Citation72 Elevated serum IL-6, which was significantly elevated up to 3 months after TBI,Citation73,Citation74 is considered a reliable biomarker of MDD,Citation75 though whether it is a biomarker for PTD remains to be determined. While prospective studies are needed to validate this hypothesis, it is reasonable to consider that individuals whose inflammation remains high chronically after TBI may transition from an adaptive immune response (initial high inflammation with return to baseline) to a chronic, maladaptive response (sustained inflammation), leading to PTD and greater disability.

Another cytokine that has shown preliminary associations with PTD is IL-7,Citation62 which has been implicated in lymphoproliferative processes needed to generate an adaptive immune response.Citation76 This connection to generating an effective immune response may explain why low levels of CSF IL-7 in the first week post-injury were inversely related to PTD at 1 year post-injury (eg, levels “below” the 25th percentile in the sample of adults with severe TBI were associated with higher risk for PTD).Citation62 This finding in severe TBI was consistent with a study in MDD in which those in the lowest tertile for serum IL-7 levels had a 3.4-fold greater risk for depression,Citation77 supporting the hypothesis that lower levels of IL-7 among those with depression reflect disruption of T-cell homeostasis as a potential pathway for inflammation-mediated depression.Citation77

IL-6 and TNF-α may also affect brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the setting of chronic stress. Increases in proinflammatory cytokines resulting from chronic stress could potentially lead to dampening of BDNF expression, as evidenced in preclinical models,Citation78 which may then contribute to depression.Citation79 BDNF levels were decreased in untreated depression, but increased with antidepressant treatment.Citation80–Citation82 Notably, in post-stroke depression, serum BDNF levels were higher during periods with no depressive symptoms, but lower in the presence of depressive symptoms.Citation83 BDNF levels in serum during the first week post-TBI may be indicative of risk for the development of PTD by 1 year.Citation84 Overall, BDNF represents a potential biomarker for risk stratification and a potential therapeutic target for both prevention and treatment of PTD.

Psychosocial risk factors for PTD

Pre-injury and comorbid personal factors, as well as changes in functional abilities and community-based participation after injury, could contribute to an adjustment-based, rather than biologically based, depression after TBI.Citation47,Citation85 Adjustment-based depression is characterized more by low self-worth, feelings of guilt, agitation, and suicidal endorsement when compared to depression resulting from maladaptive sickness behavior,Citation69,Citation70 suggesting not only distinct mechanisms for the development of PTD () but also potentially different subtypes of PTD. This point has implications for treatment decisions, as particular subtypes of PTD, such as inflammatory-induced versus adjustment-based, may be more or less responsive to pharmacological versus behavioral interventions.

Age,Citation8,Citation15 race,Citation8,Citation86 less independence in functional tasks after injury,Citation11,Citation15,Citation87–Citation89 engaging in maladaptive coping,Citation90,Citation91 and sleep disturbance or fatigueCitation46,Citation92,Citation93 were all associated with PTD. Furthermore, being unemployed or impoverished at the time of injury or substance abuse before or at the time of injury also conferred a higher likelihood of developing PTD.Citation8,Citation12,Citation13,Citation15,Citation94 Personality characteristics and pre-injury psychiatric conditions that increase the risk of sustaining a TBICitation95,Citation96 may also put individuals at greater risk for developing PTD.Citation7,Citation85,Citation94 In fact, one of the biggest predictors of PTD was a pre-injury history of depression or other psychiatric disorder.Citation7,Citation94,Citation97 However, the extent to which pre-injury mental health conditions contribute to PTD development through biological versus psychological pathways is unknown.

The appraisal of post-injury abilities compared to the appraisal of pre-injury abilities was another underlying factor related directly to the adjustment to disability that contributes significantly to the development of psychiatric disorders after TBI.Citation87,Citation98–Citation101 Individuals with TBI often over-generalize the effects their injuries have on their abilities and daily lives.Citation102,Citation103 These perceptions were strongly influenced by the individual’s ability or failure to attain post-injury goals.Citation104,Citation105 Individuals with cognitive impairment may have difficulty engaging in goal-directed, problem-solving behavior,Citation106–Citation108 resulting in poor goal attainment and contributing to PTD. Individuals with TBI engaged less frequently in goal-directed problem-solving than individuals without injuries,Citation109 often as a result of associated impairments in executive functions.Citation90,Citation110 Individuals who do engage in goal-directed problem-solving post-injury had higher self-efficacy, less perceived stress, less depression and anxiety, and overall better psychosocial functioning than those who engage in wishful thinking or avoidance behaviors after injury.Citation90,Citation102,Citation109,Citation111 Therefore, goal-directed and problem-solving behaviors may represent one effective avenue of treatment for PTD.

Management challenges

A number of systematic reviews and meta-analyses have been conducted to examine the evidence for efficacious interventions to address PTD, with very limited evidence supporting any approach.Citation27,Citation101,Citation112–Citation118 In addition to (and perhaps partly as a result of) the lack of clear recommendations and guidelines for treating PTD, studies have suggested that a relatively high proportion of individuals living in the community received limited or no treatment for PTD.Citation3,Citation119 Given the long-term consequences of PTD, research to establish evidence-based rehabilitation interventions for depression should be a high priority in rehabilitation research.Citation120–Citation122 Increasing priority should also be given to investigating personalized treatment approaches based on factors ranging from genetic variation to mental health history. Rehabilomics is a rehabilitation-centered conceptual framework that adapts the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Function, Disability, and Health to outline a personalized biopsychosocial approach to rehabilitation research and care,Citation123–Citation126 and it could serve as a contemporary framework from which to conduct innovative and effective research into personalized risk assessment and personalized rehabilitation interventions, where treatment assignment is delineated based on personal biology and other individual factors hypothesized to contribute to PTD.

Current evidence for effective treatment for PTD

The current literature does not support any gold standard for PTD treatment. Antidepressant treatment – specifically serotonergic drugs – and psychotherapeutic approaches – particularly cognitive behavioral approaches – have the best levels of evidence. To date, however, studies on effective treatments for PTD have not differentiated potential subgroups that may have differential responses to treatment.

Pharmacological interventions

Antidepressants have yielded mixed results in studies of depression treatment after neurological injury, such as TBI,Citation112,Citation113 and there is growing evidence that some antidepressants may be less effective among individuals with TBI compared to those without TBI.Citation113 The reduced treatment effectiveness of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) after TBI may be due to the high levels of inflammation post-injury. An animal model of postepilepsy depression, another condition associated with high levels of inflammation, revealed that treatment with fluoxetine alone yielded no antidepressant effects, but when paired with an IL-1Ra (an IL-1 antagonist), nearly all depressive indicators were eradicated.Citation127 Currently, treatment with SSRIs is still one of the most evidence-based approaches to PTD treatment,Citation27,Citation113,Citation128 and recent evidence suggested that one such antidepressant (sertraline) may be a promising preventative treatment for PTD.Citation129 Combination therapy with an SSRI and anti-inflammatory agent is also promising, and further study is warranted. However, it is important to note that side effects of newer-generation antidepressant drugs often overlap with and may compound symptoms after TBI.Citation130 Thus, careful consideration should be given to the relative benefits and risks of using these pharmacological agents, particularly where little is known about how they will interact with other TBI-related medical sequelae to cause adverse side effects.

Behavioral/psychological interventions

Cognitive behavioral interventions also have a growing body of evidence to support their efficacy for treating PTD,Citation131–Citation136 though to what extent any specific approach (eg, cognitive behavioral therapyCitation27,Citation134,Citation135 and problem-solving treatmentsCitation137) was better than another or better than traditional psychotherapy (eg, talk therapy and psychodynamic therapy) still remains to be determined.Citation117,Citation131 Isolating the “active ingredients” of behavioral interventions, particularly if different components are more or less effective for specific subtypes or subgroups of individuals with PTD, will inform clinical triage, training for practitioners, and systems of care.

One meta-analysis suggested that behavioral activation approaches, specifically activity scheduling, showed promise and could be integrated into holistic treatment programs to improve mood in addition to functional and community-based outcomes.Citation138 Problem-solving characterized another class of behavioral intervention that has the potential to improve mood, in addition to other rehabilitation-relevant outcomes such as goal attainment and executive function.Citation27,Citation114 Setting and attaining goals are critical components of the rehabilitation process and may be compromised by executive impairment after TBI.Citation139–Citation141 If goal attainment after TBI is compromised, it may further contribute to the discrepancy between the appraisal of one’s pre- and post-injury abilities, leading to depression. Therefore, interventions that promote goal attainment and address impairments in executive functions may prevent or improve PTD,Citation34,Citation135 particularly if it has more of an adjustment-based etiology.

A review of the literature conducted by the Brain Injury Special Interest Group of the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine (ACRM BI-ISIG) recommended metacognitive strategy training, a problem-solving-based approach, as a treatment guideline for executive dysfunction, which often manifests in disrupted behavior, after TBI.Citation142 Impairment in problem-solving mechanisms was at the core of executive dysfunction, and problem-solving was both supported and impeded by emotion after TBI.Citation143 The ACRM BI-ISIG recommended incorporating training in formal problem-solving strategies applied to everyday activities as a cornerstone of cognitive rehabilitation.Citation144 It was also recommended that treatment should be provided in a top-down manner, that is to focus on functional and activity-based goals rather than improvement of symptoms or bodily functions, to ensure generalization to non-trained goals and activities.Citation143 While these strategy-training, self-management approaches are a recommended guideline for treating executive impairments after TBI, the extent to which they improve PTD and its impact on other outcomes remains unclear. Huckans et alCitation145 conducted a pilot study examining a 6- to 8-week group-based cognitive strategy training program for veterans with a history of TBI and found increased life satisfaction and decreased depressive symptoms and cognitive complaints among those who completed the intervention. However, despite evidence that combining cognitive and emotional interventions yielded more positive outcomes than addressing cognition and emotion in isolation,Citation146,Citation147 there is little research assessing the direct effect of problem-solving approaches on PTD.

Other potential pharmacological and non- pharmacological approaches to effectively treat PTD have shown some promise, but require further study. As mentioned earlier, targeting inflammation and/or BDNF levels may help to improve depressive symptoms or prevent the transition from adaptive to maladaptive sickness behavior. There is emerging evidence for agents that selectively enhance BDNF improving depressive symptoms in MDD.Citation115 Exercise-based interventionsCitation148,Citation149 may also improve depressive symptoms partially by enhancing BDNF. Targeting inflammation through transcranial photobiomodulationCitation150 was found to improve mood in MDD and through an anti-inflammatory dietCitation58 was found to improve mood in spinal cord injury. Other potential avenues for research that may reveal effective treatments for PTD include methylphenidateCitation118,Citation151 and mindfulness-based interventions.Citation152,Citation153 Recommendations for non-pharmacological treatments of PTD, based on evidence from a systematic review conducted by the French Society of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, included structured holistic approaches and family and systemic therapies, though the authors note that this was based on low levels of evidence.Citation136 Finally, further research is required to assess the efficacy of interventions employed in clinical practice that demonstrate anecdotal success for treating PTD, but lack a sufficient evidence base.

Challenges and considerations

In addition to a lack of clear PTD treatment guidelines, there are other challenges and considerations when managing PTD. During the initial hospitalization after TBI, 95% of patients were prescribed a psychotropic medication, with over half of the medications classified as antidepressants.Citation154 Many of these antidepressants, however, were used more for sedation (eg, mirtazapine and trazodone) than for depression.Citation155 Often reasons for prescribing antidepressants in the hospital are not well documented, and patients with TBI may continue to take these antidepressants after discharge from the hospital without a clear indication as to the reason for continued use. Further, while an antidepressant may be effective in addressing other symptoms, the drug class and/or dose may not be effective in reducing depressive symptoms. Polypharmacy is also a significant concern, as individuals with TBI are prescribed multiple medications for several conditions or symptoms. In a large study of adults admitted to inpatient rehabilitation after TBI, 31.8% of patients were receiving ≥6 psychotropic medications. Similarly, a study on polypharmacy in veterans indicated that those with comorbid TBI, anxiety, and mood disorders had the highest odds (adjusted odds ratios [AOR] 15.30) of psychotropic polypharmacy (≥5 medications), and after controlling for these comorbid conditions, polypharmacy was associated with greater risk of overdose and suicidality.Citation156 Polypharmacy is also a problem when combining psychotropic medications with medications for other active medical conditions, such as preexisting chronic disease or other secondary conditions post-TBI (eg, seizures and migraine). Particular consideration should be given to drug interactions that may increase the risk of intra-cranial bleeds, such as that associated with combined use of antidepressants and nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs in the general population,Citation157 though no studies have investigated this interaction after TBI specifically. Physicians may be reluctant to prescribe antidepressants in these cases due to risk for unwanted side effects, especially if an individual had previously not responded to an initial depression treatment.

Individuals with TBI experience many barriers to care, which may be particularly compounded when seeking care for PTD. A study by Matarazzo et alCitation158 that solicited feedback from clinical providers treating veterans with a history of TBI and comorbid mental health conditions presented an illustrative example of these compounded barriers. The clinician-perceived barriers preventing veterans with TBI from seeking care included a lack of knowledge of where to go for treatment, cost of treatment, embarrassment or concern about how they would be perceived by others, and fear of it having a negative impact on their careers. Traditional mental health practitioners may not understand or know how to manage behaviors or unique emotional regulation difficulties of individuals with TBI; similarly, community-based physicians and other medical providers may not feel equipped to treat PTD or may not be aware of the unique considerations (eg, polypharmacy, contraindicated medications after TBI, and differential response to antidepressants) required when considering how to treat adults with TBI. In addition, some interventions may require modifications,Citation132,Citation135 such as pacing or presenting information in different formats, and clinicians may not know how to appropriately adapt these interventions for adults with TBI.Citation158

Other clinical considerations for PTD management include: 1) cultural values, both with regard to how they contribute to depression and how they impact perceptions about treatment;Citation159 2) pain, which co-occurs frequently with depressionCitation160 and should be managed as part of prevention and treatment of mental health conditions;Citation114 3) personalized risk and treatment response, based on personal biology and/or personal genetics,Citation161,Citation162 an emerging field that requires further study.

The evidence to support PTD treatment continues to grow, with multiple avenues to explore further. However, even the most evidence-based treatments are only effective for certain individuals. Overall, no single PTD treatment is likely to be universally effective and, therefore, personalized approaches to the research and management of PTD are necessary. The Rehabilomics framework is one tool to operationalize the multifactorial nature of PTD and provides the necessary theoretical groundwork to advance our understanding and management of PTD in the emerging practice of personalized medicine.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- HibbardMRUysalSKeplerKBogdanyJSilverJAxis I psychopathology in individuals with traumatic brain injuryJ Head Trauma Rehabil199813424399651237

- JorgeRERobinsonRGMoserDTatenoACrespo-FacorroBArndtSMajor depression following traumatic brain injuryArch Gen Psychiatry2004611425014706943

- BombardierCHFannJRTemkinNREsselmanPCBarberJDikmenSSRates of major depressive disorder and clinical outcomes following traumatic brain injuryJAMA2010303191938194520483970

- StrakowskiSMAdlerCMDelbelloMPIs depression simply a nonspecific response to brain injury?Curr Psychiatry Rep201315938623943470

- GreenBNJohnsonCDAdamsAWriting narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the tradeJ Chiropr Med20065310111719674681

- LiumbrunoGMVelatiCPasqualettiPFranchiniMHow to write a scientific manuscript for publicationBlood Transfus201311221722623356975

- AlwayYGouldKRJohnstonLMcKenzieDPonsfordJA prospective examination of Axis I psychiatric disorders in the first 5 years following moderate to severe traumatic brain injuryPsychol Med20164661331134126867715

- HartTBennEKTBagiellaEEarly trajectory of psychiatric symptoms after traumatic brain injury: relationship to patient and injury characteristicsJ Neurotrauma201431761061724237113

- Whelan-GoodinsonRPonsfordJJohnstonLGrantFPsychiatric disorders following traumatic brain injury: their nature and frequencyJ Head Trauma Rehabil200924532433219858966

- JourdanCBayenEPradat-DiehlPA comprehensive picture of 4-year outcome of severe brain injuries. Results from the PariS-TBI studyAnn Phys Rehabil Med201659210010626704071

- HartTHoffmanJMPretzCKennedyRClarkANBrennerLAA longitudinal study of major and minor depression following traumatic brain injuryArch Phys Med Rehabil20129381343134922840833

- SeelRTKreutzerJSRosenthalMHammondFMCorriganJDBlackKDepression after traumatic brain injury: a National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research Model Systems multicenter investigationArch Phys Med Rehabil200384217718412601647

- DikmenSSMachamerJEPowellJMTemkinNROutcome 3 to 5 years after moderate to severe traumatic brain injuryArch Phys Med Rehabil200384101449145714586911

- FisherLBPedrelliPIversonGLPrevalence of suicidal behaviour following traumatic brain injury: longitudinal follow-up data from the NIDRR Traumatic Brain Injury Model SystemsBrain Inj201630111311131827541868

- GuillamondeguiODMontgomerySAPhibbsFTTraumatic Brain Injury and DepressionRockville, MDAgency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US)2011 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK62061/Accessed June 30, 2014

- GlennMBO’Neil-PirozziTGoldsteinRBurkeDJacobLDepression amongst outpatients with traumatic brain injuryBrain Inj200115981181811516349

- Harrison-FelixCLWhiteneckGGJhaADeVivoMJHammondFMHartDMMortality over four decades after traumatic brain injury rehabilitation: a retrospective cohort studyArch Phys Med Rehabil20099091506151319735778

- SimpsonGTateRSuicidality in people surviving a traumatic brain injury: prevalence, risk factors and implications for clinical managementBrain Inj20072113–141335135118066936

- ReevesRRLaizerJTTraumatic brain injury and suicideJ Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv20125033238

- JorgeRERobinsonRGArndtSAre there symptoms that are specific for depressed mood in patients with traumatic brain injury?J Nerv Ment Dis1993181291998426177

- SeelRTMacciocchiSKreutzerJSClinical considerations for the diagnosis of major depression after moderate to severe TBIJ Head Trauma Rehabil20102529911220134332

- KashlubaSHanksRACaseyJEMillisSRNeuropsychologic and functional outcome after complicated mild traumatic brain injuryArch Phys Med Rehabil200889590491118452740

- FannJRKatonWJUomotoJMEsselmanPCPsychiatric disorders and functional disability in outpatients with traumatic brain injuriesAm J Psychiatry199515210149314997573589

- PagulayanKFHoffmanJMTemkinNRMachamerJEDikmenSSFunctional limitations and depression after traumatic brain injury: examination of the temporal relationshipArch Phys Med Rehabil200889101887189218929017

- HibbardMRAshmanTASpielmanLAChunDCharatzHJMelvinSRelationship between depression and psychosocial functioning after traumatic brain injuryArch Phys Med Rehabil2004854 suppl 2S43S5315083421

- BowenANeumannVConnerMTennantAChamberlainMAMood disorders following traumatic brain injury: identifying the extent of the problem and the people at riskBrain Inj19981231771909547948

- FannJRHartTSchomerKGTreatment for depression after traumatic brain injury: a systematic reviewJ Neurotrauma200926122383240219698070

- LinM-RChiuW-TChenY-JYuW-YHuangS-JTsaiM-DLongitudinal changes in the health-related quality of life during the first year after traumatic brain injuryArch Phys Med Rehabil201091347448020298842

- IfuDXKreutzerJSMarwitzJHEtiology and incidence of rehospitalization after traumatic brain injury: a multicenter analysisArch Phys Med Rehabil199980185909915377

- MarwitzJHCifuDXEnglanderJHighWMJrA multi-center analysis of rehospitalizations five years after brain injuryJ Head Trauma Rehabil200116430731711461654

- WassermanLShawTVuMKoCBollegalaDBhaleraoSAn overview of traumatic brain injury and suicideBrain Inj2008221181181918850340

- Whelan-GoodinsonRPonsfordJSchönbergerMAssociation between psychiatric state and outcome following traumatic brain injuryJ Rehabil Med2008401085085719242623

- GarrelfsSFDonker-CoolsBHPMWindHFrings-DresenMHWReturn-to-work in patients with acquired brain injury and psychiatric disorders as a comorbidity: a systematic reviewBrain Inj201529555055725625788

- HudakAMHynanLSHarperCRDiaz-ArrastiaRAssociation of depressive symptoms with functional outcome after traumatic brain injuryJ Head Trauma Rehabil2012272879822411107

- JuengstSBSwitzerGOhBMArenthPMWagnerAKConceptual model and cluster analysis of behavioral symptoms in two cohorts of adults with traumatic brain injuriesJ Clin Exp Neuropsychol201739651352427750469

- MyrgaJMJuengstSBFaillaMDCOMT and ANKK1 genetics interact with depression to influence behavior following severe TBI: an initial assessmentNeurorehabil Neural Repair2016301092093027154305

- JuengstSBMyrgaJMFannJRWagnerAKCross-lagged panel analysis of depression and behavioral dysfunction in the first year after moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injuryJ Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci Epub2017315

- RaoVLyketsosCNeuropsychiatric sequelae of traumatic brain injuryPsychosomatics20004129510310749946

- PerrinPBStevensLFSutterMReciprocal causation between functional independence and mental health 1 and 2 years after traumatic brain injury: a cross-lagged panel structural equation modelAm J Phys Med Rehabil

- WoodRLRutterfordNADemographic and cognitive predictors of long-term psychosocial outcome following traumatic brain injuryJ Int Neuropsychol Soc200612335035816903127

- UnderhillATLobelloSGStroudTPTerryKSDevivoMJFinePRDepression and life satisfaction in patients with traumatic brain injury: a longitudinal studyBrain Inj2003171197398214514448

- JuengstSBAdamsLMBognerJATrajectories of life satisfaction after traumatic brain injury: influence of life roles, age, cognitive disability, and depressive symptomsRehabil Psychol201560435336426618215

- JorgeRENeuropsychiatric consequences of traumatic brain injury: a review of recent findingsCurr Opin Psychiatry200518328929916639154

- WilliamsonMLCElliottTRBerryJWUnderhillATStavrinosDFinePRPredictors of health-related quality-of-life following traumatic brain injuryBrain Inj201327999299923781905

- DiazAPSchwarzboldMLThaisMEPsychiatric disorders and health-related quality of life after severe traumatic brain injury: a prospective studyJ Neurotrauma20122961029103722111890

- SchönbergerMHerrbergMPonsfordJFatigue as a cause, not a consequence of depression and daytime sleepiness: a cross-lagged analysisJ Head Trauma Rehabil201429542743123867997

- ZgaljardicDJSealeGSSchaeferLSTempleROForemanJElliottTRPsychiatric disease and post-acute traumatic brain injuryJ Neurotrauma201532231911192525629222

- EastonASNeutrophils and stroke – can neutrophils mitigate disease in the central nervous system?Int Immunopharmacol20131741218122523827753

- LoaneDJByrnesKRRole of microglia in neurotraumaNeurother J Am Soc Exp Neurother201074366377

- PleinesUEStoverJFKossmannTTrentzOMorganti-KossmannMCSoluble ICAM-1 in CSF coincides with the extent of cerebral damage in patients with severe traumatic brain injuryJ Neurotrauma19981563994099624625

- UzanMErmanHTanriverdiTSanusGZKafadarAUzunHEvaluation of apoptosis in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with severe head injuryActa Neurochir (Wien)20061481111571164 discussion16964558

- RaisonCLCapuronLMillerAHCytokines sing the blues: inflammation and the pathogenesis of depressionTrends Immunol2006271243116316783

- SchiepersOJGWichersMCMaesMCytokines and major depressionProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry200529220121715694227

- FelgerJCLotrichFEInflammatory cytokines in depression: neuro-biological mechanisms and therapeutic implicationsNeuroscience201324619922923644052

- DimopoulosNPiperiCSaloniciotiAElevation of plasma concentration of adhesion molecules in late-life depressionInt J Geriatr Psychiatry2006211096597116927406

- PattenSBWilliamsJVALavoratoDHPatterns of association of chronic medical conditions and major depressionEpidemiol Psychiatr Sci19 Epub20161027

- SwardfagerWRosenblatJDBenlamriMMcIntyreRSMapping inflammation onto mood: inflammatory mediators of anhedoniaNeurosci Biobehav Rev20166414816626915929

- AllisonDJDitorDSTargeting inflammation to influence mood following spinal cord injury: a randomized clinical trialJ Neuroinflammation20151220426545369

- FischerAOtteCKriegerTDecreased hydrocortisone sensitivity of T cell function in multiple sclerosis-associated major depressionPsychoneuroendocrinology201237101712171822455832

- GoldSMIrwinMRDepression and immunity: inflammation and depressive symptoms in multiple sclerosisImmunol Allergy Clin North Am200929230932019389584

- MaesMKuberaMObuchowiczwaEGoehlerLBrzeszczJDepression’s multiple comorbidities explained by (neuro)inflammatory and oxidative & nitrosative stress pathwaysNeuro Endocrinol Lett201132172421407167

- JuengstSBKumarRGFaillaMDGoyalAWagnerAKAcute inflammatory biomarker profiles predict depression risk following moderate to severe traumatic brain injuryJ Head Trauma Rehabil201530320721824590155

- DevotoCArcurioLFettaJInflammation relates to chronic behavioral and neurological symptoms in military with traumatic brain injuriesCell Transplant Epub20161012

- ThomasAJPerryRKalariaRNOakleyAMcMeekinWO’BrienJTNeuropathological evidence for ischemia in the white matter of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in late-life depressionInt J Geriatr Psychiatry200318171312497551

- BolesJGoyalAKumarRWagnerAChronic Inflammation after Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: Characterization and Associations with OutcomeNashville, TN2013

- AnismanHMeraliZPoulterMOHayleySCytokines as a precipitant of depressive illness: animal and human studiesCurr Pharm Des200511896397215777247

- DantzerRO’ConnorJCFreundGGJohnsonRWKelleyKWFrom inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brainNat Rev Neurosci200891465618073775

- MyersJProinflammatory cytokines and sickness behavior: implications for depression and cancer-related symptomsOncol Nurs Forum200835580280718765326

- DantzerRCytokine, sickness behavior, and depressionImmunol Allergy Clin North Am200929224726419389580

- CharltonBGThe malaise theory of depression: major depressive disorder is sickness behavior and antidepressants are analgesicMed Hypotheses200054112613010790737

- GoldPWThe organization of the stress system and its dysregulation in depressive illnessMol Psychiatry2015201324725486982

- LittrellJLTaking the perspective that a depressive state reflects inflammation: implications for the use of antidepressantsFront Psychol2012329722912626

- KumarRGDiamondMLBolesJAAcute interleukin-6 trajectories after TBI: relationship to isolated injury and polytrauma and associations with outcomeJ Neurotrauma20143112A104A105

- KumarRGBolesJAWagnerAKChronic inflammation after severe traumatic brain injury: characterization and associations with outcome at 6- and 12-moths post-injuryJ Head Trauma Rehabil201530636938124901329

- MössnerRMikovaOKoutsilieriEConsensus paper of the WFSBP Task Force on Biological Markers: biological markers in depressionWorld J Biol Psychiatry20078314117417654407

- KatzmanSDHoyerKKDoomsHOpposing functions of IL-2 and IL-7 in the regulation of immune responsesCytokine201156111612121807532

- LehtoSMHuotariANiskanenLSerum IL-7 and G-CSF in major depressive disorderProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry201034684685120382196

- YouZLuoCZhangWPro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines expression in rat’s brain and spleen exposed to chronic mild stress: involvement in depressionBehav Brain Res2011225113514121767575

- MartinowichKManjiHLuBNew insights into BDNF function in depression and anxietyNat Neurosci20071091089109317726474

- KaregeFPerretGBondolfiGSchwaldMBertschyGAubryJ-MDecreased serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels in major depressed patientsPsychiatry Res2002109214314811927139

- SenSDumanRSanacoraGSerum brain-derived neurotrophic factor, depression, and antidepressant medications: meta-analyses and implicationsBiol Psychiatry200864652753218571629

- HashimotoKBrain-derived neurotrophic factor as a biomarker for mood disorders: an historical overview and future directionsPsychiatry Clin Neurosci201064434135720653908

- YangLZhangZSunDLow serum BDNF may indicate the development of PSD in patients with acute ischemic strokeInt J Geriatr Psychiatry201126549550220845405

- FaillaMDJuengstSBArenthPMWagnerAKPreliminary associations between brain-derived neurotrophic factor, memory impairment, functional cognition, and depressive symptoms following severe TBINeurorehabil Neural Repair201630541943026276123

- RogersJMReadCAPsychiatric comorbidity following traumatic brain injuryBrain Inj20072113–141321133318066935

- PerrinPBKrchDSutterMRacial/ethnic disparities in mental health over the first two years after traumatic brain injury: a model systems studyArch Phys Med Rehabil201495122288229525128715

- MalecJFBrownAWMoessnerAMStumpTEMonahanPA preliminary model for posttraumatic brain injury depressionArch Phys Med Rehabil20109171087109720599048

- SchönbergerMPonsfordJGouldKRJohnstonLThe temporal relationship between depression, anxiety, and functional status after traumatic brain injury: a cross-lagged analysisJ Int Neuropsychol Soc201117578178721729404

- JourdanCBayenEVallat-AzouviCLate functional changes post-severe traumatic brain injury are related to community reentry support: results from the PariS-TBI cohortJ Head Trauma Rehabil Epub201715

- AnsonKPonsfordJCoping and emotional adjustment following traumatic brain injuryJ Head Trauma Rehabil200621324825916717502

- FinsetAAnderssonSCoping strategies in patients with acquired brain injury: relationships between coping, apathy, depression and lesion locationBrain Inj2000141088790511076135

- RaoVMcCannUHanDBergeyASmithMTDoes acute TBI-related sleep disturbance predict subsequent neuropsychiatric disturbances?Brain Inj2014281202624328797

- Beaulieu-BonneauSOuelletMCFatigue in the first year after traumatic brain injury: course, relationship with injury severity, and correlatesNeuropsychol Rehabil119 Epub201641

- BombardierCHHoekstraTDikmenSFannJRDepression trajectories during the first year after traumatic brain injuryJ Neurotrauma201633232115212426979826

- VassalloJLProctor-WeberZLebowitzBKCurtissGVanderploegRDPsychiatric risk factors for traumatic brain injuryBrain Inj200721656757317577707

- FannJRLeonettiAJaffeKKatonWJCummingsPThompsonRSPsychiatric illness and subsequent traumatic brain injury: a case control studyJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry200272561562011971048

- KumarRGBrackenMBClarkANNickTGMelguizoMSSanderAMRelationship of preinjury depressive symptoms to outcomes 3 mos after complicated and uncomplicated mild traumatic brain injuryAm J Phys Med Rehabil201493868770224743469

- OwnsworthTFlemingJHainesTDevelopment of depressive symptoms during early community reintegration after traumatic brain injuryJ Int Neuropsychol Soc201117111211921083964

- CantorJBAshmanTASchwartzMEThe role of self-discrepancy theory in understanding post-traumatic brain injury affective disorders: a pilot studyJ Head Trauma Rehabil200520652754316304489

- DraperKPonsfordJLong-term outcome following traumatic brain injury: a comparison of subjective reports by those injured and their relativesNeuropsychol Rehabil200919564566119629849

- PonsfordJSloanSSnowPTraumatic Brain Injury Rehabilitation for Everyday Adaptive LivingHove, East Sussex, New York, NYPsychology Press2012

- MooreADStambrookMCoping strategies and locus of control following traumatic brain injury: relationship to long-term outcomeBrain Inj2009 Available from: http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/02699059209008129Accessed September 26, 2013

- MooreADStambrookMCognitive moderators of outcome following traumatic brain injury: a conceptual model and implications for rehabilitationBrain Inj1995921091307787832

- BanduraALockeEANegative self-efficacy and goal effects revisitedJ Appl Psychol2003881879912675397

- TromblyCARadomskiMVTrexelCBurnett-SmithSEOccupational therapy and achievement of self-identified goals by adults with acquired brain injury: phase IIAm J Occup Ther200256548949812269503

- DuncanJEmslieHWilliamsPJohnsonRFreerCIntelligence and the frontal lobe: the organization of goal-directed behaviorCogn Psychol19963032573038660786

- LevineBSchweizerTAO’ConnorCRehabilitation of executive functioning in patients with frontal lobe brain damage with goal management trainingFront Hum Neurosci20115921369362

- BergquistTFJacketsMPAwareness and goal setting with the traumatically brain injuredBrain Inj1993732752828508184

- TombergTToomelaAPulverATikkACoping strategies, social support, life orientation and health-related quality of life following traumatic brain injuryBrain Inj200519141181119016286333

- KrpanKMLevineBStussDTDawsonDRExecutive function and coping at one-year post traumatic brain injuryJ Clin Exp Neuropsychol2007291364617162720

- RutterfordNAWoodRLEvaluating a theory of stress and adjustment when predicting long-term psychosocial outcome after brain injuryJ Int Neuropsychol Soc200612335936716903128

- PriceARaynerLOkon-RochaEAntidepressants for the treatment of depression in neurological disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trialsJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry201182891492321558287

- Neurobehavioral Guidelines Working GroupWardenDLGordonBGuidelines for the pharmacologic treatment of neurobehavioral sequelae of traumatic brain injuryJ Neurotrauma200623101468150117020483

- LuautéJHamonetJPradat-DiehlPSOFMERBehavioral and affective disorders after brain injury: French guidelines for prevention and community supportsAnn Phys Rehabil Med2016591687326697992

- KaplanGBVasterlingJJVedakPCBrain-derived neurotrophic factor in traumatic brain injury, post-traumatic stress disorder, and their comorbid conditions: role in pathogenesis and treatmentBehav Pharmacol2010215–642743720679891

- Stalder-LüthyFMesserli-BürgyNHoferHFrischknechtEZnojHBarthJEffect of psychological interventions on depressive symptoms in long-term rehabilitation after an acquired brain injury: a systematic review and meta-analysisArch Phys Med Rehabil20139471386139723439410

- GertlerPTateRLCameronIDNon-pharmacological interventions for depression in adults and children with traumatic brain injuryCochrane Database Syst Rev201512CD009871

- VattakatucheryJLathifNJoyJCavannaARickardsHPharmacological interventions for depression in people with traumatic brain injury: systematic reviewJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry2014858e3

- VangelSJJrRapportLJHanksRABlackKLLong-term medical care utilization and costs among traumatic brain injury survivorsAm J Phys Med Rehabil200584315316015725788

- RapoportMJMccullaghSStreinerDFeinsteinAThe clinical significance of major depression following mild traumatic brain injuryPsychosomatics2003441313712515835

- KendallETerryDPredicting emotional well-being following traumatic brain injury: a test of mediated and moderated modelsSoc Sci Med200969694795419616354

- GordonWAZafonteRCiceroneKTraumatic brain injury rehabilitation: state of the scienceAm J Phys Med Rehabil200685434338216554685

- WagnerAKTBI translational rehabilitation research in the 21st century: exploring a Rehabilomics research modelEur J Phys Rehabil Med201046454955621224787

- WagnerAKRehabilomics: a conceptual framework to drive biologics researchPM R201136 suppl 1S28S3021703576

- WagnerAKZitelliKTA rehabilomics focused perspective on molecular mechanisms underlying neurological injury, complications, and recovery after severe TBIPathophysiology2013201394822444246

- CrownoverJWagnerAChapter 8 – rehabilomics: protein, genetic, and hormonal biomarkers in TBIWangKZhangZKobeissyFBiomarkers of Brain Injury & Neurological DisordersBoca RatonCRC Press/Taylor & Francis Group Co2014236273

- PinedaEAHenslerJGSankarRShinDBurkeTFMazaratiAMInterleukin-1β causes fluoxetine resistance in an animal model of epilepsy-associated depressionNeurotherapeutics20129247748522427156

- PlantierDLuautéJSOFMER GroupDrugs for behavior disorders after traumatic brain injury: systematic review and expert consensus leading to French recommendations for good practiceAnn Phys Rehabil Med2016591425726797170

- JorgeREAcionLBurinDIRobinsonRGSertraline for preventing mood disorders following traumatic brain injury: a randomized clinical trialJAMA Psychiatry201673101041104727626622

- CarvalhoAFSharmaMSBrunoniARVietaEFavaGAThe safety, tolerability and risks associated with the use of newer generation antidepressant drugs: a critical review of the literaturePsychother Psychosom201685527028827508501

- AshmanTCantorJBTsaousidesTSpielmanLGordonWComparison of cognitive behavioral therapy and supportive psychotherapy for the treatment of depression following traumatic brain injury: a randomized controlled trialJ Head Trauma Rehabil201429646747825370439

- PonsfordJLeeNKWongDEfficacy of motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression symptoms following traumatic brain injuryPsychol Med20164651079109026708017

- FannJRBombardierCHVannoySTelephone and in-person cognitive behavioral therapy for major depression after traumatic brain injury: a randomized controlled trialJ Neurotrauma2015321455725072405

- SimpsonGKTateRLWhitingDLCotterRESuicide prevention after traumatic brain injury: a randomized controlled trial of a program for the psychological treatment of hopelessnessJ Head Trauma Rehabil201126429030021734512

- ArundineABradburyCLDupuisKDawsonDRRuttanLAGreenREACognitive behavior therapy after acquired brain injury: maintenance of therapeutic benefits at 6 months posttreatmentJ Head Trauma Rehabil201227210411222411108

- WiartLLuautéJStefanAPlantierDHamonetJNon pharmacological treatments for psychological and behavioural disorders following traumatic brain injury (TBI). A systematic literature review and expert opinion leading to recommendationsAnn Phys Rehabil Med2016591314126776320

- RathJFSimonDLangenbahnDMSherrRLDillerLGroup treatment of problem-solving deficits in outpatients with traumatic brain injury: a randomised outcome studyNeuropsychol Rehabil2003134461488

- CuijpersPvan StratenAWarmerdamLBehavioral activation treatments of depression: a meta-analysisClin Psychol Rev200727331832617184887

- HartTEvansJSelf-regulation and goal theories in brain injury rehabilitation: the journal of head trauma rehabilitationJ Head Trauma Rehabil200621214215516569988

- LevackWMTaylorKSiegertRJDeanSGMcPhersonKMWeather-allMIs goal planning in rehabilitation effective? A systematic reviewClin Rehabil200620973975517005499

- HoferHHoltforthMGFrischknechtEZnojHJFostering adjustment to acquired brain injury by psychotherapeutic interventions: a preliminary studyAppl Neuropsychol2010171182620146118

- CiceroneKDLangenbahnDMBradenCEvidence-based cognitive rehabilitation: updated review of the literature from 2003 through 2008Arch Phys Med Rehabil201192451953021440699

- GordonWACantorJAshmanTBrownMTreatment of post-TBI executive dysfunction: application of theory to clinical practiceJ Head Trauma Rehabil200621215616716569989

- HaskinsECCognitive Rehabilitation Manual: Translating Evidence-Based Recommendations into PracticeReston, VAACRM Pub2012

- HuckansMPavawallaSDemaduraTA pilot study examining effects of group-based Cognitive Strategy Training treatment on self-reported cognitive problems, psychiatric symptoms, functioning, and compensatory strategy use in OIF/OEF combat veterans with persistent mild cognitive disorder and history of traumatic brain injuryJ Rehabil Res Dev2010471436020437326

- MateerCASiraCSCognitive and emotional consequences of TBI: intervention strategies for vocational rehabilitationNeuroRehabilitation200621431532617361048

- MateerCASiraCSO’ConnellMEPutting Humpty Dumpty together again: the importance of integrating cognitive and emotional interventionsJ Head Trauma Rehabil2005201627515668571

- HoffmanJMBellKRPowellJMA randomized controlled trial of exercise to improve mood after traumatic brain injuryPM R201021091191920970760

- WiseEKHoffmanJMPowellJMBombardierCHBellKRBenefits of exercise maintenance after traumatic brain injuryArch Phys Med Rehabil20129381319132322840829

- CassanoPPetrieSRHamblinMRHendersonTAIosifescuDVReview of transcranial photobiomodulation for major depressive disorder: targeting brain metabolism, inflammation, oxidative stress, and neurogenesisNeurophotonics20163303140426989758

- LeeHKimS-WKimJ-MShinI-SYangS-JYoonJ-SComparing effects of methylphenidate, sertraline and placebo on neuropsychiatric sequelae in patients with traumatic brain injuryHum Psychopharmacol20052029710415641125

- KhusidMAVythilingamMThe emerging role of mindfulness meditation as effective self-management strategy, part 1: clinical implications for depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and anxietyMil Med2016181996196827612338

- BédardMFelteauMMarshallSMindfulness-based cognitive therapy: benefits in reducing depression following a traumatic brain injuryAdv Mind Body Med20122611420

- HammondFMBarrettRSSheaTPsychotropic medication use during inpatient rehabilitation for traumatic brain injuryArch Phys Med Rehabil2015968 supplS256.e14S253.e1426212402

- AlbrechtJSKiptanuiZTsangYDepression among older adults after traumatic brain injury: a national analysisAm J Geriatr Psychiatry201523660761425154547

- CollettGASongKJaramilloCAPotterJSFinleyEPPughMJPrevalence of central nervous system polypharmacy and associations with overdose and suicide-related behaviors in Iraq and Afghanistan War veterans in VA care 2010–2011Drugs Real World Outcomes201634552

- ShinJ-YParkM-JLeeSHRisk of intracranial haemorrhage in antidepressant users with concurrent use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: nationwide propensity score matched studyBMJ2015351h351726173947

- MatarazzoBBSignoracciGMBrennerLAOlson-MaddenJHBarriers and facilitators in providing community mental health care to returning veterans with a history of traumatic brain injury and co-occurring mental health symptomsCommunity Ment Health J201652215816426308836

- RoyDJayaramGVassilaAKeachSRaoVDepression after traumatic brain injury: a biopsychosocial cultural perspectiveAsian J Psychiatr201513566125453532

- Sullivan-SinghSJSawyerKEhdeDMComorbidity of pain and depression among persons with traumatic brain injuryArch Phys Med Rehabil20149561100110524561058

- FaillaMDBurkhardtJNMillerMAVariants of SLC6A4 in depression risk following severe TBIBrain Inj201327669670623672445

- LanctôtKLRapoportMJChanFGenetic predictors of response to treatment with citalopram in depression secondary to traumatic brain injuryBrain Inj2010247–895996920515362