Abstract

Background

Burden of treatment refers to the workload of health care and its impact on patient functioning and well-being. There are a number of patient-reported measures that assess burden of treatment in single diseases or in specific treatment contexts. A review of such measures could help identify content for a general measure of treatment burden that could be used with patients dealing with multiple chronic conditions. We reviewed the content and psychometric properties of patient-reported measures that assess aspects of treatment burden in three chronic diseases, ie, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and heart failure.

Methods

We searched Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, Ovid PsycINFO, and EBSCO CINAHL through November 2011. Abstracts were independently reviewed by two people, with disagreements adjudicated by a third person. Retrieved articles were reviewed to confirm relevance, with patient-reported measures scrutinized to determine consistency with the definition of burden of treatment. Descriptive information and psychometric properties were extracted.

Results

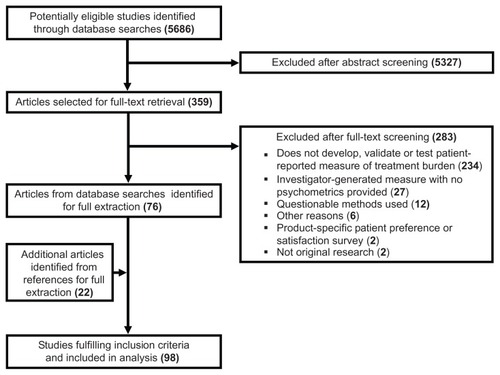

A total of 5686 abstracts were identified from the database searches. After abstract review, 359 full-text articles were retrieved, of which 76 met our inclusion criteria. An additional 22 articles were identified from the references of included articles. From the 98 studies, 57 patient-reported measures of treatment burden (full measures or components within measures) were identified. Most were multi-item scales (89%) and assessed treatment burden in diabetes (82%). Only 15 measures were developed using direct patient input and had demonstrable evidence of reliability, scale structure, and multiple forms of validity; six of these demonstrated evidence of sensitivity to change. We identified 12 content domains common across measures and disease types.

Conclusion

Available measures of treatment burden in single diseases can inform derivation of a patient-centered measure of the construct in patients with multiple chronic conditions. Patients should take part in developing the measure to ensure salience and relevance.

Introduction

Burden of treatment is the workload of health care and its impact on patient functioning and well-being.Citation1 “Workload” consists of the demands placed on a patient by treatment for condition(s) and any associated self-care (eg, health monitoring, diet, exercise). “Impact” refers to the effect of treatment and self-care on a patient’s behavioral, cognitive, physical, and psychosocial well-being. Burden of treatment is an important clinical issue because it can lead to lower rates of adherence with prescribed treatments and self-care,Citation2,Citation3 and ultimately result in worse clinical outcomes, including more hospitalizations,Citation4 higher mortality,Citation4,Citation5 and poorer health-related quality of life.Citation6,Citation7 In order to understand better how burden of treatment can influence critical patient outcomes, robust means of measuring it must be available. Like health-related quality of life, burden of treatment is best understood from the perspective of the individual patient. Hence, it is best assessed through direct patient query.

Patients coping with multiple chronic health conditions are especially vulnerable to a sense of burden with their treatment regimen because they are often required to engage in a complex array of self-care activities in order to maintain health.Citation8 The number of US adults with multiple chronic health conditions is projected to rise from 57 million in 2000 to 81 million by 2020.Citation9 There is a paucity of available options for assessing burden of treatment in this growing patient population,Citation10 including no comprehensive, multidomain patient-reported measure (PRM). However, there are a number of PRMs that assess burden of treatment in single diseases or specific treatments. A review of such measures, focused specifically on identifying similarities in content across diseases and treatment, could help to determine the content for a general comprehensive measure of treatment burden, that is amenable for use across chronic diseases or with patients coping with more than one health condition.

Building a new PRM relies on triangulation of multiple and diverse methods, often used in a stepwise fashion.Citation11–Citation14 The first steps usually involve direct patient query of the phenomena of interest and a literature review of existing instruments in related areas.Citation11,Citation14 We outlined a preliminary measurement framework of treatment burden in a recent study.Citation1 The framework was derived from 32 semistructured interviews with patients, all with complex self-care regimens (including polypharmacy) and most coping with multiple chronic health conditions. The framework is currently undergoing further qualitative testing in a new sample of socioeconomically disadvantaged patients. Currently, there are no systematic reviews of PRMs of treatment burden. The review of PRMs described in this report is designed to augment and verify the developing measurement framework, while also informing item content for a new comprehensive measure of treatment burden.

We searched the available scientific literature for PRMs of treatment burden in three disease types, ie, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and heart failure. These three chronic diseases were selected because they all can involve rather complicated long-term management plans requiring considerable time, effort, and financial investment from patients,Citation6,Citation15,Citation16 and because of their interrelationship with one another, including the fact that diagnosis of one can raise the risk of diagnosis of the others.Citation17 The PRMs identified contain components consistent with our above definition of treatment burden and could include full scales, scales within measures, or other scorable components, like single items. The systematic review has three objectives. First, to identify PRMs of treatment burden in diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and heart failure, including full measures, scales within measures, or other scorable components within measures; second, to identify common content domains of treatment burden, given that common domains that cut across measures and disease types can help inform the content of a general measure of treatment burden; and third, to summarize measure characteristics and psychometric properties, eg, reliability, scaling structure, validity, and sensitivity to change. While documentation of these performance characteristics could help investigators to select an appropriate measure of treatment burden for use in the diseases targeted, the primary aim of this summary is to identify psychometrically sound measures, scales, and items that can inform the content of a general (not disease-specific) measure of burden.

Materials and methods

Database search and abstract review

We searched Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, Ovid PsycINFO, and EBSCO CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) through November 2011. An information specialist (PJE) created and ran the search strategies. Sample terms used in the searches included “self-care”, “workload”, “burden”, and “lifestyle” crossed with “questionnaire”, “scale”, “measure”, and “survey” and the three targeted diseases, diabetes (types 1 and 2), chronic kidney disease, and heart failure. Full search strategies for each database are accessible at http://mayoresearch.mayo.edu/mayo/research/hsr/burden-of-treatment.cfm.

Abstracts were downloaded into a reference software library (Endnote X4®), then uploaded to a web-based systematic review software program (DistillerSR) where they were reviewed. All abstracts were double-reviewed for relevance and fit with the inclusion criterion of an article reflecting original research describing the development, validation, or use of a PRM of treatment burden in diabetes, chronic kidney disease, or heart failure. To assist reviewers in selecting appropriate measures, a working definition was provided on the abstraction form (“the burden of treatment is the negative impact of treatment and care on a patient’s daily routine through the investment of time, money, and effort into health care”). Disagreements between abstract reviewers were adjudicated by either DTE or KJY, given their expertise with PRMs and familiarity with the burden of treatment construct that was discussed by these two authors prior to and during adjudication.

Article retrieval, determination of inclusion, and data extraction

Full-text articles of relevant abstracts were retrieved, uploaded to DistillerSR, and screened for relevance by DTE and KJY. Together, these authors carefully scrutinized each article, reviewing the items on each PRM (as included in the article or as identified through additional search for the actual measure), and determining which aspects of each measure were consistent with the working definition of treatment burden. This step was critical because in many instances an entire measure was not relevant, but portions of it were (eg, subscales). The components of each measure consistent with our definition of treatment burden were eligible for data extraction. A component (ie, full measure or subscale within a measure) was included for extraction if at least half of its items reflected treatment burden. Reference sections of the included articles were a secondary source of relevant articles missed by the database searches.

Any English language article describing the development or use of a PRM of treatment burden (as defined above) in one of the targeted diseases was included for data extraction. Articles were excluded if they: did not develop, validate, or use a PRM of treatment burden; did not provide any psychometric characteristics of the measure; described a product or device-specific patient preference or satisfaction measure; employed questionable methods (eg, very small sample sizes); or did not describe an original research study. For each article, data extractors were provided with the name of the measure as well as the component(s) of the measure that reflected treatment burden. They were instructed to extract descriptive information about the study (eg, sample size, age and gender of participants, disease focus) and psychometric data on the measure. When available, the following psychometric information were extracted for each measure: whether direct patient input was used during development; reliability, specifically internal consistency and test-retest; scale analysis, specifically factor analysis and item-total correlations; convergent and discriminant validity, ie, convergence with conceptually similar measures and divergence with conceptually dissimilar measures; known-groups validity or the ability of the PRM to differentiate known patient groups; concurrent validity or correlation of the PRM with meaningful clinical characteristics; and sensitivity to change or the ability of the PRM to reflect underlying change in patient status over time.

Data extractors (JLR, AJ, JSE) were trained by DTE. Prior to beginning the task, each extractor completed two sample extractions, with their results checked and didactic feedback provided by DTE, who also provided continued scientific support throughout the process. The extraction form was created by RJM, and TAE maintained the DistillerSR database, managed the extraction process including reviewer assignments, and provided technical support. All data extractions were checked for accuracy by one of the PRM experts (DTE or KJY).

Results

Study screening and inclusion

shows the process by which studies were screened and selected for inclusion. The database search yielded 5686 articles, of which 359 were retrieved for full-text review. After review of the full texts, 283 articles were excluded from further consideration, mostly because they did not develop, validate, or use a PRM of treatment burden. Several retained articles referenced other studies of possible relevance. Twenty-two of these were retrieved and deemed eligible for data extraction. Hence, a total of 98 articles were targeted for data extraction.

Identified measures of treatment burden

Fifty-seven PRMs of treatment burden were identified in the 98 articles selected for inclusion (see for a list of the measures). Most (47, 82%) assessed treatment burden in diabetes, but six (11%) assessed treatment burden in kidney disease and four (7%) in heart failure. Based on their focus and contents, we categorized the measures into one of the following eight types: treatment/regimen-related impact and burden, barriers to self-care, distress, insulin treatment, family conflict/strain, general diabetes quality of life, glucose monitoring, or treatment satisfaction. Most of the measures represented in (51, 89%) are scored as multi-item scales (ie, multiple items are combined to form a single score). The rest (6, 11%) score responses to only single items. This includes measures made up of only a single, standalone itemCitation18–Citation20 as well as measures made up of multiple items that report scores for only individual items (eg, Survey of Treatment Burdens in Diabetes,Citation2,Citation21 Perceived Difficulties in Diabetes Self-Care,Citation22 and Perceptions of Insulin Shots and FingersticksCitation23). Finally, some measures (12, 21%, all in diabetes) are suitable for administration in children or adolescents, including a few that are specifically tailored to this population (eg, the DISABKIDS Diabetes moduleCitation24 and the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 3.0 Diabetes moduleCitation25).

Table 1 Identified patient-reported measures assessing burden of treatment (57)

Common content domains of treatment burden

provides a summary of all measures including a description of the contents of each measure and a summary of key psychometric properties. The instrument name and specific subscales relevant to treatment burden (or scorable components in the case of single items) appear in the first two columns of the table. This information, along with a review of item wording of each relevant measure, provides a general sense of the common content domains reflected in the measures. We identified the following 12 content domains as common to two or more of the identified measures: emotional impact/regimen-related distress,Citation6,Citation23,Citation24,Citation26–Citation38 family conflict/unsupportive behavior from others,Citation39–Citation44 convenience of treatment (eg, insulin, oral medications),Citation2,Citation6,Citation19,Citation21,Citation22,Citation24,Citation25,Citation29,Citation38,Citation45–Citation57 self-care convenience (eg, exercise, foot care, overall impression of self-care),Citation22,Citation24,Citation25,Citation37,Citation38,Citation48,Citation51,Citation56–Citation60 monitoring burden (eg, glucose monitoring),Citation2,Citation21,Citation22,Citation24,Citation25,Citation38,Citation49,Citation53,Citation56–Citation58,Citation60–Citation63 lifestyle impact (including social restrictions and work interference),Citation2,Citation6,Citation21,Citation24,Citation33,Citation36,Citation37,Citation46,Citation47,Citation50,Citation52,Citation58,Citation62,Citation64,Citation65 scheduling flexibility,Citation26,Citation29,Citation46,Citation47 medication side effects,Citation29,Citation46,Citation47,Citation55 diet/food-related problems,Citation2,Citation21,Citation22,Citation25,Citation32,Citation38,Citation48,Citation49,Citation53,Citation55–Citation57,Citation60,Citation66 overall treatment burden,Citation18,Citation67 device function/bother (eg, insulin delivery device, kidney dialysis),Citation6,Citation34,Citation35,Citation52 and economic burden.Citation20,Citation51,Citation59,Citation68 Several measures assess multiple content domains. For example, the DISABKIDS Diabetes module and the Personal Diabetes Questionnaire each assess five content domains. Eight other measures assess four content domains (Barriers to Adherence Questionnaire, Diabetes Medication Satisfaction Measure, Diabetes Medication Treatment Satisfaction Tool, General Barriers to Diabetes Self-Management, PedsQL 3.0 Diabetes module, Perceived Difficulties in Diabetes Self-Care, Perceptions About Medications for Diabetes, and the Survey of Treatment Burdens in Diabetes).

Table 2 Summary of scale characteristics and psychometric properties

Psychometric properties of treatment burden measures

The 98 studies included in this review provided a considerable amount of scale and psychometric data on the identified measures. Detailed tables featuring all extracted data are accessible at http://mayoresearch.mayo.edu/mayo/research/hsr/burden-of-treatment.cfm. provides a summary of the extracted data for each measure. Measurement properties featured in the table include patient input, reliability (internal consistency and test-retest), scale analysis (factor analysis, item-total correlation), convergent and discriminant validity, known-groups/concurrent validity, and sensitivity to change. Consistency of each property with a minimum standard of acceptability is indicated in the table.

Patient input

Directly incorporating patient views during item generation is now considered standard practice when developing a patient-centered, self-report measure.Citation11 This is typically done using qualitative methods, such as individual interviews or focus groups; however, patient surveys are sometimes used as well. More than half of the measures (38, 67%) showed evidence of being developed from direct patient input via individual interviews, focus groups, surveys, or combinations of these methods ().

Reliability

Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) and test-retest (Pearson r or intraclass correlation) were frequently reported measures of reliability. The standard threshold for acceptable reliability of measures used for group comparison is 0.70.Citation69 Most of the measures (46, 81%) demonstrated acceptable reliability, usually internal consistency (). Nine measures also demonstrated acceptable test-retest reliability, including the Diabetes Family Adherence Measure, Glucose Monitoring Survey, Insulin Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire, Perceptions about Medications for Diabetes, Problem Areas in Diabetes, Treatment-Related Impact Measure-Diabetes, Treatment-Related Impact Measure-Diabetes Device, Hemodialysis Stressor Scale, and Renal Adherence Attitudes Questionnaire. Retest magnitudes may have been attenuated in certain measures due to long retest intervals. For example, retest intervals for the Barriers to Adherence and Diabetes Family Behavior Checklist were reported as six months,Citation40,Citation56 a span of time in which patient status could have changed. Reliability was unavailable for all measures scoring single items.

Scale analysis

Content domains apparent in multi-item scales can be verified using factor analysis and item-total scale correlations. Exploratory factor analytic techniques like principal components analysis and/or confirmatory factor analysis were used in a number of studies, and supported the treatment burden domains identified in most measures (32, 56%). Exploratory factor analyses typically support content domains through reporting of variance explained; confirmatory factor analysis supports content domains through report of goodness of fit indices. Fifteen of these measures also demonstrated adequate item-total scale correlations (ie, Barriers to Diabetes Adherence, Diabetes-39, Diabetes Family Support and Conflict Scale, Diabetes Fear of Injecting and Self-testing Questionnaire, Diabetes Health Profile, Diabetes-specific Quality of Life Scale, Diabetic Foot Ulcer Scale, Insulin Treatment Appraisal Scale, Insulin Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire, Patient Satisfaction with Insulin Therapy, Perceptions About Medications for Diabetes, Hemodialysis Stressor Scale, Beliefs about Medicine Compliance Scale, Beliefs about Diet Compliance Scale, and Dietary Sodium Restriction Questionnaire). An adequate item-total scale correlation is >0.20.Citation14

Convergent and discriminant validity

Convergent validity was determined by the degree of convergence (ie, correlation) of the treatment burden measure with other conceptually similar measures; discriminant validity was determined by the degree of divergence (ie, lack of correlation or low correlation) with other conceptually dissimilar measures. A medium-sized correlation (r ≥ 0.30)Citation70 may be used to support convergent validity. Discriminant validity is supported by a pattern of low correlations with measures and indicators that are unrelated to the target measure.Citation14 As shown in , less than half of the measures (23, 40%) demonstrated evidence of convergent or discriminant validity. In most instances, convergent validity alone was supported. For example, in validating the Insulin Treatment Appraisal Scale, Snoek et al found negative insulin appraisal scores were associated with more total diabetes distress on the Problem Areas in Diabetes questionnaire (r = 0.33).Citation31 Among patients with end-stage renal disease, Griva et al found that the total treatment disruptiveness score of the Treatment Effects Questionnaire was strongly associated with the total illness disruptiveness score of the Illness Effects Questionnaire (r = 0.83).Citation36 Only four measures showed any evidence of discriminant validity (Diabetes Family Adherence Measure, Insulin Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire, Problem Areas in Diabetes, and Treatment Effects Questionnaire).Citation32,Citation36,Citation39,Citation52 For example, while the coercion scale of the Diabetes Family Adherence Measure has been found to be highly associated with the nonsupportive behaviors scale of the Diabetes Family Behavior Checklist (r = 0.65), it is much less associated with the warmth/caring (r = 0.22) and guidance/control (r = 0.14) subscales of the Diabetes Family Behavior Scale.Citation39 Evidence of convergent and discriminant validity was absent for measures scoring single items.

Known-groups and concurrent validity

Clinical utility of the measures was observed in the following ways: by noting differences in scores across meaningful groups of patients (ie, known-groups validity), and by noting correlations of scores with meaningful clinical, health status, or sociodemographic indicators (ie, concurrent validity). Known-groups validity was considered supported if clinically differentiable patient groups differed significantly on the measure in expected ways.Citation71 Concurrent validity was evidenced by a statistically significant correlation of at least a moderate magnitude, or in this case ≥ 0.20.Citation70 As shows, most of the measures (47, 82%) demonstrated evidence of known-groups and/or concurrent validity. This included five of the six measures scoring single items.Citation2,Citation18,Citation20,Citation22,Citation23,Citation72 Sample patient groupings on which measure scores significantly differed include continuous glucose monitoring (users versus nonusers),Citation62,Citation73 insulin use (yes versus no, type of insulin),Citation31,Citation74,Citation75 dialysis type,Citation76 insurance status,Citation57 and mental health status.Citation6,Citation77 Clinical indicators such as hemoglobin A1c and adherence with self-care were consistently associated with measure scores across numerous studies, with greater treatment burden associated with higher hemoglobin A1cCitation6,Citation25,Citation27,Citation38,Citation39,Citation41,Citation49,Citation54 and poorer adherence with self-care.Citation2,Citation26,Citation28,Citation40,Citation56,Citation63,Citation64 Other variables frequently associated with measure scores included age (younger age, more burden)Citation6,Citation28,Citation78,Citation79 and self-reported health (poorer health, more burden).Citation49,Citation67,Citation79

Sensitivity to change

The ability of the treatment burden measure to detect any change in patient status over time (ie, sensitivity to change)Citation14 was noted in a few measures (11, 19%, ). A commonly observed result was a statistically significant decline in treatment burden after a successful medical or psychoeducational intervention.Citation45,Citation58,Citation80–Citation86 In only three studies was a standard index of sensitivity also calculated, specifically, Cohen’s effect size.Citation45,Citation81,Citation85

Patient-centered measures with evidence of reliability and validity

Of the 57 measures of treatment burden identified in this analysis, 15 (26%) were developed with direct patient input and had demonstrable evidence of reliability and multiple forms of validity. This included the following measures: Diabetes-39, Diabetes Distress Scale (including the 2-item, 3-item, and 4-item short versions), Diabetes Family Conflict Scale, Diabetes Health Profile, Diabetes Medication Satisfaction Measure, Diabetes-specific Quality of Life Scale, Diabetic Foot Ulcer Scale, Insulin Treatment Appraisal Scale, Insulin Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire, Problem Areas in Diabetes, Treatment-Related Impact Measure-Diabetes, and Treatment-Related Impact Measure-Diabetes Device. Six of these measures also demonstrated evidence of sensitivity to change (Diabetes Distress Scale, Diabetes Family Conflict Scale, Diabetes Health Profile, Diabetes Medication Satisfaction Measure, Diabetes-specific Quality of Life Scale, and Problem Areas in Diabetes).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of PRMs for burden of treatment. In this review, we identified 57 measures across three chronic conditions, ie, diabetes, kidney disease, and heart failure. There appear to be a number of adequate PRMs tapping various aspects of treatment and self-care burden, mainly in diabetes. Possible explanations for the imbalance in representation favoring diabetes include the self-management complexity of this disease, the fact that diabetes impacts both children and adults, and the speed with which new treatments and management technologies become available for this disease. Indeed, 40% of the diabetes studies reviewed received funding support from a pharmaceutical or device manufacturer, compared with only 18% for kidney disease and heart failure studies combined. While our intent in this analysis was not to evaluate the sufficiency of treatment burden measurement in the three targeted conditions, the results appear to support the need for development of more measures in kidney disease and heart failure. No single kidney disease or heart failure measure satisfied all of the psychometric criteria reviewed. Most of the measures reviewed (89%) are scored as multi-item scales in which multiple items are aggregated to form a score. Measures scoring responses to single items tended to have poorer psychometric properties, with reliability infrequently reported. Also, the availability of measures suitable for administration in children (specifically diabetes) signals the relevance of treatment burden beyond adults.

Several common content domains emerged that cut across the measures and disease types, supporting conceptualization of a general burden of treatment construct. shows the 12 content domains that were represented in two or more PRMs. Seven of these domains (emotional impact or regimen-related distress, treatment convenience, lifestyle impact, medication side effects, diet or food-related problems, device function or bother, and economic burden) were represented in PRMs from at least two of the targeted diseases. Economic burden was represented in PRMs of all three diseases. The heterogeneity of the content domains that emerge from these measures lends support to a multidimensional conceptualization of treatment burden, a quality supported by other recent research on the construct,Citation87–Citation89 including our own formative qualitative work.Citation1

Table 3 Content domains common across burden of treatment measures

Identifying PRMs of treatment burden required identifying measures of a wide number of related constructs like “barriers to self-care”, “distress”, “treatment impact”, “treatment satisfaction”, and “quality of life”. Measures of these constructs, many of which are multidimensional, contain elements reflective of treatment burden as well as other concepts. Hence, we needed to examine carefully the components of each measure, including the contents of subscales and even individual items. For example, the Treatment-Related Impact Measure-Diabetes, a measure of treatment impact, contains five subscales, three of which reflect treatment burden (treatment burden, daily life, and psychological health) and two of which do not (management beliefs and compliance). The Diabetes-39, a measure of diabetes-specific quality of life, also consists of five subscales, but only the 12-item control subscale specifically addresses the degree to which treatment and self-care affect quality of life. The other four subscales do not differentiate burden due to the illness from burden due to treatment or self-care. However, there were some instances in which entire measures were judged consistent with the construct of treatment burden (eg, the Diabetes Family Conflict Scale and the Hemodialysis Stressor Scale).

Standard psychometric performance criteria were used to evaluate the quality of each of the identified PRMs. While a review of performance characteristics could help select a measure of treatment burden for use in one of the three diseases targeted, our principal aim was to identify psychometrically sound scales and items that could inform item content for a general non-disease-specific measure. Our review identified 15 measures with acceptable psychometric characteristics in most of the categories extracted including direct patient input, reliability, scaling structure (ie, factor analysis), convergent and/or discriminant validity, and known-groups and concurrent validity. Six of these 15 measures were also sensitive to changes in patient health status over time (the Diabetes Distress Scale, Diabetes Family Conflict Scale, Diabetes Health Profile, Diabetes Medication Satisfaction Measure, Diabetes-specific Quality of Life Scale, and Problem Areas in Diabetes). Authors of a few measures did stipulate clinically meaningful score differences or threshold cut points for serious problems.Citation6,Citation23,Citation90,Citation91 There was no evidence of use of more modern psychometric approaches such as item response theory. This is a notable absence given that item response theory-based metrics like item-information and scale-information function and analyses like differential item functioning can provide critical psychometric data that classical test theory methods cannot.

Methodological challenges

There were several challenges associated with conducting this systematic review. Given that most conceptualizations of treatment burden are of relatively recent origin, developing a literature search strategy that is both sensitive and specific proved difficult. Gallacher et al reported the same challenge in a review of qualitative literature.Citation87 Inherent limitations in the way in which articles are currently indexed required that we develop and run a rather broad, highly sensitive but nonspecific, database search strategy. Consequently, our searches identified a large number of articles, most of which failed to meet inclusion criteria for the review. Of the total number of abstracts identified (5686), only 6% (359) were deemed relevant enough to warrant article retrieval. Of these, only 76 articles (21%) fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were extracted, or slightly over 1% of the total number of abstracts identified by the searches. Further, our belief that the burden of treatment is a multidimensional construct also contributed to the expansive nature of the search strategy. Since we expected some variability in the content domains represented in the different measures, the searches consisted of a number of expanded Boolean searches using the “or” connector rather than more limited searches using “and”. The nonspecificity of the searches was also compounded by the number of terms synonymous with “patient-reported measure”, including “measure”, “questionnaire”, “instrument”, “tool”, “scale”, and “survey”. Finally, during examination of full-text articles, it became apparent that most measures were not designed to assess treatment burden exclusively; hence, it took considerable effort to scrutinize and tease out those specific components of each measure that addressed the construct as we defined it.

Limitations

Our review does have a few limitations. The concept of a general burden of treatment is relatively novel, although we have shown that a number of previously developed PRMs do assess components of it within individual disease contexts. Given that the current state of the science is actively evolving, there is bound to be some disagreement about what does and what does not constitute treatment burden. We attempted to identify domains and PRMs consistent with our own definition of the construct.Citation1 It is possible that a different conceptualization could result in identification of a slightly different set of domains and measures. Second, in order to make for a manageable review, we needed to limit the number of chronic conditions. It is possible that a different set of targeted conditions might reveal other content domains not represented in this review. However, we are encouraged by the findings of a recently published concept analysis of the treatment burden literature in six major chronic illnesses that confirms many of the same domains uncovered in our review of measures, including emotional impact, treatment and self-care convenience, lifestyle impact, scheduling flexibility, medication side effects, device function/bother, and economic burden.Citation89 Third, study heterogeneity in both methods and the reporting of results precluded use of a more formal quantitative pooling technique such as meta-analysis. Fourth, only English language studies were selected for extraction; hence, we may have missed a few relevant measures unavailable in English. Finally, while all abstracts were reviewed by two people and disagreements were adjudicated by a third reviewer, it is possible that a relevant article was inadvertently excluded by the two abstract reviewers.

Conclusion

This systematic review of PRMs is a companion piece to our earlier qualitative study that articulated a patient-informed conceptual framework of the burden of treatment.Citation1 Most of the content domains identified in this review coincide with themes and subthemes articulated in the framework. Three domains, ie, emotional impact, diet or food-related problems, and device function or bother, are currently not represented in the framework. However, we are continuing to refine this conceptual framework with additional qualitative data from interviews with socioeconomically disadvantaged patients. The ultimate result of all these efforts will be a measurement framework that will provide the foundation on which a patient-centered measure of treatment burden will be built.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Mayo Clinic’s Center for Translational Science Activities through grant number UL1 RR024150 from the National Center for Research Resources, a component of the National Institutes of Health. DTE, KJY, and VMM are part of the International Minimally Disruptive Medicine Workgroup. Workgroup members include Victor M Montori, Carl May, Nilay Shah, Frances Mair, Sara Macdonald, Nathan Shippee, Katie Gallacher, David T Eton, Djenane Oliveira, Kathleen J Yost, Robert Stroebel, AnneRose Kaiya, Leona Han, and Amy Bodde. We thank Elie Akl for assistance with an early protocol for the review and Hannah Fields, Krista Bohlen, and Muhammad Mustafa for assistance with abstract screening.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- EtonDTRamalho de OliveiraDEggintonJSBuilding a measurement framework of burden of treatment in complex patients with chronic conditions: a qualitative studyPatient Relat Outcome Meas201233949 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3506008/Accessed April 25, 201323185121

- VijanSHaywardRARonisDLHoferTPBrief report: the burden of diabetes therapy: implications for the design of effective patient-centered treatment regimensJ Gen Intern Med20052047948215963177

- HaynesRBMcDonaldHPGargAXHelping patients follow prescribed treatment: clinical applicationsJAMA20022882880288312472330

- HoPMRumsfeldJSMasoudiFAEffect of medication nonadherence on hospitalization and mortality among patients with diabetes mellitusArch Intern Med20061661836184117000939

- RasmussenJNChongAAlterDARelationship between adherence to evidence-based pharmacotherapy and long-term mortality after acute myocardial infarctionJAMA200729717718617213401

- BrodMHammerMChristensenTLessardSBushnellDMUnderstanding and assessing the impact of treatment in diabetes: the Treatment-Related Impact Measures for Diabetes and Devices (TRIM-Diabetes and TRIM-Diabetes Device)Health Qual Life Outcomes200978319740444

- PifferiMBushADi CiccoMHealth-related quality of life and unmet needs in patients with primary ciliary dyskinesiaEur Respir J20103578779419797134

- MayCMontoriVMMairFSWe need minimally disruptive medicineBMJ2009339b280319671932

- WuSGreenAProjection of Chronic Illness Prevalence and Cost InflationWashington, DCRAND Health2000

- TranVTMontoriVMEtonDTBaruchDFalissardBRavaudPDevelopment and description of measurement properties of an instrument to assess treatment burden among patients with multiple chronic conditionsBMC Med2012106822762722

- McCollEDeveloping questionnairesFayersPHaysRDAssessing Quality of Life in Clinical Trials: Methods and Practice2nd edNew York, NYOxford2005

- HaysRDFayersPEvaluating multi-item scalesFayersPHaysRDAssessing Quality of Life in Clinical Trials: Methods and Practice2nd edNew York, NYOxford2005

- ReeveBBFayersPApplying item response theory modelling for evaluating questionnaire item and scale propertiesFayersPHaysRDAssessing Quality of Life in Clinical Trials: Methods and Practice2nd edNew York, NYOxford2005

- StreinerDLNormanGRHealth Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use4th edOxford, UKOxford University Press2008

- CowieMRZaphiriouAManagement of chronic heart failureBMJ200232542242512193359

- JansenDLGrootendorstDCRijkenMPre-dialysis patients’ perceived autonomy, self-esteem and labor participation: associations with illness perceptions and treatment perceptions. A cross-sectional studyBMC Nephrology2010113521138597

- NicholsGAMolerEJCardiovascular disease, heart failure, chronic kidney disease and depression independently increase the risk of incident diabetesDiabetologia20115452352621107522

- van der DoesFEde NeelingJNSnoekFJRandomized study of two different target levels of glycemic control within the acceptable range in type 2 diabetes. Effects on well-being at 1 yearDiabetes Care199821208520939839098

- LermanIDiazJPIbarguengoitiaMENonadherence to insulin therapy in low-income, type 2 diabetic patientsEndocr Pract200915414619211396

- SpertusJDeckerCWoodmanCEffect of difficulty affording health care on health status after coronary revascularizationCirculation20051112572257815883210

- VijanSStuartNSFitzgeraldJTBarriers to following dietary recommendations in type 2 diabetesDiabet Med200522323815606688

- ToljamoMHentinenMAdherence to self-care and social supportJ Clin Nurs20011061862711822512

- HoweCJRatcliffeSJTuttleADoughertySLipmanTHNeedle anxiety in children with type 1 diabetes and their mothersMCN, Am J Matern Child Nurs201136253121164314

- BaarsRMAthertonCIKoopmanHMBullingerMPowerMThe European DISABKIDS project: development of seven condition-specific modules to measure health related quality of life in children and adolescentsHealth Qual Life Outcomes200537016283947

- VarniJWBurwinkleTMJacobsJRGottschalkMKaufmanFJonesKLThe PedsQL in type 1 and type 2 diabetes: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Generic Core Scales and type 1 Diabetes ModuleDiabetes Care20032663163712610013

- MulvaneySAHoodKKSchlundtDGDevelopment and initial validation of the barriers to diabetes adherence measure for adolescentsDiabetes Res Clin Pract201194778321737172

- FisherLGlasgowREMullanJTSkaffMMPolonskyWHDevelopment of a brief diabetes distress screening instrumentAnn Fam Med2008624625218474888

- PolonskyWHFisherLEarlesJAssessing psychosocial distress in diabetes: development of the diabetes distress scaleDiabetes Care20052862663115735199

- MonahanPOLaneKAHayesRPMcHorneyCAMarreroDGReliability and validity of an instrument for assessing patients’ perceptions about medications for diabetes: the PAM-DQual Life Res20091894195219609723

- MollemaEDSnoekFJPouwerFHeineRJvan der PloegHMDiabetes Fear of Injecting and Self-Testing Questionnaire: a psychometric evaluationDiabetes Care20002376576910840993

- SnoekFJSkovlundSEPouwerFDevelopment and validation of the insulin treatment appraisal scale (ITAS) in patients with type 2 diabetesHealth Qual Life Outcomes200756918096074

- SnoekFJPouwerFWelchGWPolonskyWHDiabetes-related emotional distress in Dutch and US diabetic patients: cross-cultural validity of the problem areas in diabetes scaleDiabetes Care2000231305130910977023

- WelchJLPerkinsSMEvansJDBajpaiSDifferences in perceptions by stage of fluid adherenceJ Ren Nutr20031327528114566764

- BaldreeKSMurphySPPowersMJStress identification and coping patterns in patients on hemodialysisNurs Res1982311071126926648

- BihlMAFerransCEPowersMJComparing stressors and quality of life of dialysis patientsANNA J19881527373345098

- GrivaKJayasenaDDavenportAHarrisonMNewmanSPIllness and treatment cognitions and health related quality of life in end stage renal diseaseBr J Health Psychol200914173418435864

- MeadowsKSteenNMcCollEThe Diabetes Health Profile (DHP): a new instrument for assessing the psychosocial profile of insulin requiring patients – development and psychometric evaluationQual Life Res199652422548998493

- StetsonBSchlundtDRothschildCFloydJERogersWMokshagundamSPDevelopment and validation of The Personal Diabetes Questionnaire (PDQ): a measure of diabetes self-care behaviors, perceptions and barriersDiab Res Clin Pract201191321332

- LewinABGeffkenGRWilliamsLBDukeDCStorchEASilversteinJHDevelopment of the Diabetes Family Adherence Measure (D-FAM)Children’s Health Care2010391533

- SchaferLCMcCaulKDGlasgowRESupportive and nonsupportive family behaviors: relationships to adherence and metabolic control in persons with type I diabetesDiabetes Care198691791853698784

- HoodKKButlerDAAndersonBJLaffelLMUpdated and revised Diabetes Family Conflict ScaleDiabetes Care2007301764176917372149

- PaddisonCAMFamily support and conflict among adults with type 2 diabetes: development and testing of a new measureEur Diabetes Nursing201072933

- HarrisMAGrecoPWysockiTElder-DandaCWhiteNHAdolescents with diabetes from single-parent, blended, and intact families: Health-related and family functioningFam Syst and Health199917181196

- TalbotFNouwenAGingrasJGosselinMThe assessment of diabetes-related cognitive and social factors: The Multidimensional Diabetes QuestionnaireJ Behav Med1997202913129212382

- PeyrotMRubinRREffect of technosphere inhaled insulin on quality of life and treatment satisfactionDiabetes Technol Ther201012495520082585

- BrodMSkovlundSEWittrup-JensenKUMeasuring the impact of diabetes through patient report of treatment satisfaction, productivity and symptom experienceQual Life Res20061548149116547787

- AndersonRTGirmanCJPawaskarMDDiabetes medication satisfaction toolDiabetes Care200932515318931098

- BottUMuhlhauserIOvermannHBergerMValidation of a diabetes-specific quality-of-life scale for patients with type 1 diabetesDiabetes Care1998217577699589237

- MollemEDSnoekFJHeineRJAssessment of perceived barriers in self-care of insulin-requiring diabetic patientsPatient Educ Couns1996292772819006243

- PeyrotMRubinRRValidity and reliability of an instrument for assessing health-related quality of life and treatment preferences: the insulin delivery system rating questionnaireDiabetes Care200528535815616233

- PeyrotMRubinRRFactors associated with persistence and resumption of insulin pen use for patients with type 2 diabetesDiabetes Technol Ther201113434821175270

- AndersonRTSkovlundSEMarreroDDevelopment and validation of the insulin treatment satisfaction questionnaireClin Ther20042656557815189754

- WeijmanIRosWJRuttenGESchaufeliWBSchabracqMJWinnubstJAThe role of work-related and personal factors in diabetes self-managementPatient Educ Couns200559879616198222

- CappelleriJCGerberRAKouridesIAGelfandRADevelopment and factor analysis of a questionnaire to measure patient satisfaction with injected and inhaled insulin for type 1 diabetesDiabetes Care2000231799180311128356

- BennettSJMilgromLBChampionVHusterGABeliefs about medication and dietary compliance in people with heart failure: An instrument development studyHeart Lung1997262732799257137

- GlasgowREMcCaulKDSchaferLCBarriers to regimen adherence among persons with insulin-dependent diabetesJ Behav Med1986965773517352

- GlasgowREHampsonSEStryckerLARuggieroLPersonal-model beliefs and social-environmental barriers related to diabetes self-managementDiabetes Care1997205565619096980

- RubinRRPeyrotMTreatment satisfaction and quality of life for an integrated continuous glucose monitoring/insulin pump system compared to self-monitoring plus an insulin pumpJ Diabetes Sci Technol200931402141020144395

- AbetzLSuttonMBradyLMcNultyPGagnonDDThe Diabetic Foot Ulcer Scale (DFS): a quality of life instrument for use in clinical trialsPractical Diabetes Int200219167175

- TuKSBarchardKAn assessment of diabetes self-care barriers in older adultsJ Community Health Nurs1993101131188340799

- Diabetes Research in Children Network Study GroupYouth and parent satisfaction with clinical use of the GlucoWatch G2 Biographer in the management of pediatric type 1 diabetesDiabetes Care2005281929193516043734

- Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Continuous Glucose Monitoring Study GroupValidation of measures of satisfaction with and impact of continuous and conventional glucose monitoringDiabetes Technol Ther20101267968420799388

- WagnerJMalchoffCAbbottGInvasiveness as a barrier to self-monitoring of blood glucose in diabetesDiabetes Technol Ther2005761261916120035

- LewisKSBradleyCKnightGBoultonAJWardJDA measure of treatment satisfaction designed specifically for people with insulin-dependent diabetesDiabet Med198852352422967144

- RusheHMcGeeHMAssessing adherence to dietary recommendations for hemodialysis patients: the Renal Adherence Attitudes Questionnaire (RAAQ) and the Renal Adherence Behaviour Questionnaire (RABQ)J Psychosom Res1998451491579753387

- BentleyBLennieTABiddleMChungMLMoserDKDemonstration of psychometric soundness of the Dietary Sodium Restriction Questionnaire in patients with heart failureHeart Lung20093812112819254630

- BoyerJGEarpJAThe development of an instrument for assessing the quality of life of people with diabetes. Diabetes-39Med Care1997354404539140334

- FerransCEPowersMJKaschCRSatisfaction with health care of hemodialysis patientsRes Nurs Health1987103673743423308

- FrostMHReeveBBLiepaAMStaufferJWHaysRDWhat is sufficient evidence for the reliability and validity of patient-reported outcome measures?Value Health200710 Suppl 2S94S10517995479

- CohenJStatistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences2nd edHillsdale, NJLawrence Erlbaum Associates1988

- OsobaDKingMMeaningful differencesFayersPHaysRDAssessing Quality of Life in Clinical Trials: Methods and Practice2nd edNew York, NYOxford2005

- ConardMWHeidenreichPRumsfeldJSWeintraubWSSpertusJPatient-reported economic burden and the health status of heart failure patientsJ Card Fail20061236937416762800

- HalfordJHarrisCDetermining clinical and psychological benefits and barriers with continuous glucose monitoring therapyDiabetes Technol Ther20101220120520151770

- CappelleriJCCefaluWTRosenstockJKouridesIAGerberRATreatment satisfaction in type 2 diabetes: a comparison between an inhaled insulin regimen and a subcutaneous insulin regimenClin Ther20022455256412017400

- NicolucciAMaioneAFranciosiMQuality of life and treatment satisfaction in adults with type 1 diabetes: a comparison between continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion and multiple daily injectionsDiabet Med20082521322018201210

- GrivaKDavenportAHarrisonMNewmanSAn evaluation of illness, treatment perceptions, and depression in hospital- vs home-based dialysis modalitiesJ Psychosom Res20106936337020846537

- KokoszkaAPouwerFJodkoASerious diabetes-specific emotional problems in patients with type 2 diabetes who have different levels of comorbid depression: a Polish study from the European Depression in Diabetes (EDID) Research ConsortiumEur Psychiatry20092442543019541457

- TanseyMLaffelLChengJSatisfaction with continuous glucose monitoring in adults and youths with type 1 diabetesDiabet Med2011281118112221692844

- SnoekFJMollemaEDHeineRJBouterLMvan der PloegHMDevelopment and validation of the diabetes fear of injecting and self-testing questionnaire (D-FISQ): first findingsDiabet Med1997148718769371481

- BottUEbrahimSHirschbergerSSkovlundSEEffect of the rapid-acting insulin analogue insulin aspart on quality of life and treatment satisfaction in patients with type 1 diabetesDiabet Med20032062663412873289

- BrodMValensiPShabanJABushnellDMChristensenTLPatient treatment satisfaction after switching to NovoMix 30 (BIAsp 30) in the IMPROVE study: an analysis of the influence of prior and current treatment factorsQual Life Res2010191285129320602172

- GeorgeJTValdovinosAPRussellIClinical effectiveness of a brief educational intervention in type 1 diabetes: results from the BITES (Brief Intervention in Type 1 diabetes, Education for Self-efficacy) trialDiabet Med2008251447145319046244

- KeersJCGroenHSluiterWJBoumaJLinksTPCost and benefits of a multidisciplinary intensive diabetes education programmeJ Eval Clin Pract20051129330315869559

- PeyrotMRubinRRPolonskyWHBestJHPatient reported outcomes in adults with type 2 diabetes on basal insulin randomized to addition of mealtime pramlintide or rapid-acting insulin analogsCurr Med Res Opin2010261047105420199136

- TsaySLLeeYCLeeYCEffects of an adaptation training programme for patients with end-stage renal diseaseJ Adv Nurs200550394615788064

- de WitMDelmarre-van de WaalHABokmaJAFollow-up results on monitoring and discussing health-related quality of life in adolescent diabetes care: benefits do not sustain in routine practicePediatr Diabetes20101117518119538516

- GallacherKJaniBMorrisonDQualitative systematic reviews of treatment burden in stroke, heart failure and diabetes – methodological challenges and solutionsBMC Med Res Methodol2013131023356353

- GallacherKMayCRMontoriVMMairFSUnderstanding patients’ experiences of treatment burden in chronic heart failure using normalization process theoryAnn Fam Med2011923524321555751

- SavAKingMAWhittyJABurden of treatment for chronic illness: a concept analysis and review of the literatureHealth Expect1312013 [Epub ahead of print.]

- BrodMChristensenTKongsoJHBushnellDMExamining and interpreting responsiveness of the Diabetes Medication Satisfaction measureJ Med Econ20091230931619811109

- SimmonsJHMcFannKKBrownACReliability of the Diabetes Fear of Injecting and Self-Testing Questionnaire in pediatric patients with type 1 diabetesDiabetes Care20073098798817392558

- KhattabMKhaderYSAl-KhawaldehAAjlouniKFactors associated with poor glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetesJ Diabetes Complications201024848919282203

- PeyrotMRubinRRPatient-reported outcomes for an integrated real-time continuous glucose monitoring/insulin pump systemDiabetes Technol Ther200911576219132857

- KhaderYSBatainehSBatayhaWThe Arabic version of Diabetes-39: psychometric properties and validationChronic Illn2008425726319091934

- TriefPMTeresiJAIzquierdoRPsychosocial outcomes of telemedicine case management for elderly patients with diabetes: the randomized IDEATel trialDiabetes Care2007301266126817325261

- OttJGreeningLPalardyNHolderbyADeBellWKSelf-efficacy as a mediator variable for adolescents’ adherence to treatment for insulin-dependent diabetes mellitusChildren’s Health Care2000294763

- AndersonBJHolmbeckGIannottiRJDyadic measures of the parent-child relationship during the transition to adolescence and glycemic control in children with type 1 diabetesFam Syst Health20092714115219630455

- Muller-GodeffroyETreichelSWagnerVMInvestigation of quality of life and family burden issues during insulin pump therapy in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus – a large-scale multicentre pilot studyDiabet Med20092649350119646189

- SanderEPOdellSHoodKKDiabetes-specific family conflict and blood glucose monitoring in adolescents with type 1 diabetes: mediational role of diabetes self-efficacyDiabetes Spectr2010238994

- de WitMDelemarre-van de WaalHABokmaJAMonitoring and discussing health-related quality of life in adolescents with type 1 diabetes improve psychosocial well-being: a randomized controlled trialDiabetes Care2008311521152618509204

- CleveringaFGMinkmanMHGorterKJvan den DonkMRuttenGEDiabetes Care Protocol: effects on patient-important outcomes. A cluster randomized, non-inferiority trial in primary careDiabet Med20102744245020536517

- GorterKJTuytelGJde LeeuwRRBensingJMRuttenGEOpinions of patients with type 2 diabetes about responsibility, setting targets and willingness to take medication. A cross-sectional surveyPatient Educ Couns201184566120655164

- WilliamsSAPollackMFDiBonaventuraMEffects of hypoglycemia on health-related quality of life, treatment satisfaction and healthcare resource utilization in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitusDiabetes Res Clin Pract20119136337021251725

- SchoenbergNEDrungleSCBarriers to non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) self-care practices among older womenJ Aging Health20011344346611813736

- BannCMFehnelSEGagnonDDDevelopment and validation of the Diabetic Foot Ulcer Scale-short form (DFS-SF)Pharmacoeconomics2003211277129014986739

- ChaplinJEHanasRLindATolligHWramnerNLindbladBAssessment of childhood diabetes-related quality-of-life in West SwedenActa Paediatr20099836136618976373

- WenLKParchmanMLShepherdMDFamily support and diet barriers among older Hispanic adults with type 2 diabetesFam Med20043642343015181555

- BodeBShelmetJGoochBPatient perception and use of an insulin injector/glucose monitor combined deviceDiabetes Educ20043030130915095520

- BrodMChristensenTBushnellDMaximizing the value of validation findings to better understand treatment satisfaction issues for diabetesQual Life Res2007161053106317516149

- BrodMCobdenDLammertMBushnellDRaskinPExamining correlates of treatment satisfaction for injectable insulin in type 2 diabetes: lessons learned from a clinical trial comparing biphasic and basal analoguesHealth Qual Life Outcomes20075817286868

- FarmerAJOkeJStevensRHolmanRRDifferences in insulin treatment satisfaction following randomized addition of biphasic, prandial or basal insulin to oral therapy in type 2 diabetesDiabetes Obes Metab2011131136114121767341

- AllanCLFlettBDeanHJQuality of life in First Nation youth with type 2 diabetesMatern Child Health J200812S103S109

- McCartyRLWeberWJLootsBComplementary and alternative medicine use and quality of life in pediatric diabetesJ Altern Complement Med20101616517320180689

- McGuireBEMorrisonTGHermannsNShort-form measures of diabetes-related emotional distress: the Problem Areas in Diabetes Scale (PAID)-5 and PAID-1Diabetologia201053666919841892

- MurphySPPowersMJJalowiecAPsychometric evaluation of the Hemodialysis Stressor ScaleNurs Res1985343683713852248

- BennettSJPerkinsSMLaneKAForthoferMABraterDCMurrayMDReliability and validity of the compliance belief scales among patients with heart failureHeart Lung20013017718511343003

- NieuwenhuisMMWvan der WalMHLJaarsmaTThe body of knowledge on compliance in heart failure patients: we are not there yetJ Cardiovasc Nurs201126212821127428

- LennieTAWorrall-CarterLHammashMRelationship of heart failure patients’ knowledge, perceived barriers, and attitudes regarding low-sodium diet recommendations to adherenceProg Cardiovasc Nurs20082361118326994