Abstract

Purpose

Psychosis is very common in later stages of Parkinson’s disease (PD) patients, but its prevalence in newly diagnosed patients is not rare. The use of antipsychotics in PD patients is complex given their association with worsening Parkinsonian motor symptoms and increased mortality rate. This study aims to examine factors that affect the use of antipsychotics in newly diagnosed PD patients and to identify changes in prescribing over time.

Patients and Methods

The Secure Anonymized Information Linkage (SAIL) databank was used to identify a cohort of newly diagnosed PD patients aged 40 years and older in Wales. The cohort was longitudinally examined over 17 years to determine the incidence of new antipsychotic use. Logistic regression models were used to analyze the data and were adjusted for several potential confounding variables.

Results

A total of 9142 PD patients were identified after applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, of whom 58.6% were male. During the first year of PD diagnosis, 12% of the patients developed psychosis and were prescribed antipsychotics. Quetiapine was the most commonly prescribed (49%), followed by risperidone (10.7%). The use of antipsychotics in newly diagnosed PD patients was significantly lower in the years 2009–2016 compared to 2000–2008 (OR 0.37, 95% CI 0.32–0.43). Other significant prescribing factors included patient’s age and history of dementia.

Conclusion

A dramatic decline in antipsychotic use was identified across years, showing adherence to warnings against use of antipsychotics for PD patients. Given that psychosis is prevalent in PD patients, the continuous assessment of the safety risks of antipsychotics is a matter of priority.

Introduction

Psychosis is very common in Parkinson’s disease (PD) patients.Citation1 It is estimated that psychosis (visual hallucinations and delusions) affect 40% of PD patients.Citation2 Although new reports suggest an early emergence of minor hallucinations in PD patients even before the occurrence of motor symptoms,Citation3 significant psychosis is not common in the first stages of PD; rather, most patients develop psychosis in the advanced stages of PD.Citation2,Citation4 Psychotic episodes in PD may occur as a result of the disease itself, or they may be caused by some PD medications, such as dopamine agonists (DAs).Citation5 Therefore, it is important when treating psychosis to first manage the PD medications and doses, especially in early stages of the disease, and then consider antipsychotic medications if needed.Citation1 Episodes of hallucinations are more common in the late stages of PD and are the main predictor of nursing home placement in PD patients.Citation6

The use of antipsychotics in PD patients is complex, since antipsychotics block D2 dopaminergic receptors, which may lead to extrapyramidal side effects such as dyskinesia and Parkinson-like motor symptoms.Citation7 The second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), also known as atypical antipsychotics, are safer and cause fewer Parkinson-like symptoms compared to the first generation (FGAs) or typical antipsychotics.Citation8 Patients who use typical antipsychotics are more likely to receive PD medications (to control Parkinson-like symptoms) compared to atypical antipsychotic users.Citation9 In general, and particularly among atypical antipsychotics, clozapine and quetiapine are recommended for use in PD patients with psychosis.Citation10 The efficacy of quetiapine has not been confirmed in randomized clinical trials; nevertheless, it has been suggested that quetiapine should be used first in PD psychosis.Citation10 Clozapine has an approved indication for treating psychosis in PD patients and it lacks the Parkinson-like symptoms;Citation11 however, it is considered to be a second-line treatment after quetiapine due to its risk of agranulocytosis and its requirement for continuous blood monitoring.Citation10

Parkinson-like symptoms are not the only safety issue related to the use of antipsychotics. Based on several reports, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a warning in 2005 regarding the risk of death associated with the use of atypical antipsychotics in patients with dementia.Citation12 This warning was extended to include the typical antipsychotics in 2008.Citation13 Based on these reports, the Banerjee report was published in the UK in 2009 and called for immediate action to reduce the amount of antipsychotics prescribed to dementia patients and to identify ways to manage this issue.Citation14 Recent studies have extended this warning of higher mortality rate to use of antipsychotics in PD patients.Citation15,Citation16 In these studies, typical antipsychotics were more likely to cause death compared to atypical antipsychotics.Citation15,Citation16 It is important to recognize that the high mortality among PD patients who used antipsychotics is not necessarily caused by the use of antipsychotics. Other factors can contribute to increased mortality rates such as greater age, being male, and psychotic episodes themselves,Citation17 which makes attributing the higher mortality rate to antipsychotics alone a matter of controversy.

Some drugs used in the treatment of dementia, such as rivastigmine (a cholinesterase inhibitor), show some evidence of hallucination reduction and improved psychotic symptoms in PD patients, although rivastigmine has a slower response compared to atypical antipsychotics.Citation18 The recent National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines did not recommend rivastigmine as part of therapy; however, further research was recommended to compare rivastigmine with atypical antipsychotics in managing psychosis in PD patients.Citation19

The prevalence of antipsychotic use in PD patients has been measured in multiple studies.Citation20–Citation22 Many of these studies focused on psychosis in the later stages of PD, and concluded that antipsychotic use was high and should be decreased.Citation20–Citation22 However, psychosis in early stages of PD stages is not rare,Citation3 and the use of antipsychotics during this stage is under researched and needs more attention from researchers. If reducing antipsychotic use in the later stages of PD is desirable,Citation2 then reducing use in the early stages of PD is a priority.

The primary objective of this study was to examine the trend in the use of antipsychotics after PD diagnosis in early PD patients who had psychosis and to determine whether the FDA safety warnings regarding the association of antipsychotics with a higher mortality rate decreased antipsychotic use in these patients. The secondary objective was to assess to what extent rivastigmine and other anti-dementia drugs were used to treat psychosis in PD patients.

Patients and Methods

Design and Data Source

This is a repeated cross-sectional study that examined the trend of antipsychotic use during the first year after PD diagnosis between 2000 and 2016. The Secure Anonymized Information Linkage (SAIL) databank was used to obtain the data for this study. SAIL contains the Welsh Longitudinal General Practice (WLGP) primary care dataset for at least 80% of the patients in Wales. SAIL is a central repository that was created by the Health Information Research Unit (HIRU) in the College of Medicine at Swansea University.Citation23 The individual-level data contained in SAIL include but are not limited to GPs, hospital episodes, outpatient visits, demographics, and social deprivation data.Citation23 This study was approved by SAIL’s independent Information Governance Review Panel (ref 0507). The data accessed in the SAIL databank complies with relevant data protection and privacy regulations.

Identifying Early (Newly Diagnosed) PD Patients

Eligibility criteria included individuals with a first Read Code of a definitive PD diagnosis in GP data (Appendix 1). The Read Code system is a hierarchical system that covers most clinical terms, including diagnoses and drugs.Citation24 The Read Codes indicating a definitive PD diagnosis were used and validated in a previous study.Citation25 Patients were excluded for the following reasons: less than 40 years of age, taking any antiparkinsonian drug before PD diagnosis, no prescription of any antiparkinsonian drug within one year after PD diagnosis, a first code of PD within 6 months from SAIL registration date, death within a year of PD diagnosis, and previous antipsychotic use within the year prior to PD diagnosis, as antipsychotics can cause Parkinson-like symptoms which could be mistakenly diagnosed as PD.Citation26

Identifying Psychosis Diagnosis and Antipsychotics

The purpose of this study was to identify the incidence of new cases of antipsychotic use to treat psychosis in the first year after PD diagnosis. To be considered an antipsychotic user, first, a patient was required to have a new Read Code of psychosis diagnosis (Appendix 1) that appeared in the data after the diagnosis of PD diagnosis. Additionally, the Read Code for antipsychotics must have appeared after the diagnosis of psychosis and within the first year after PD diagnosis. Appendix 2 lists drugs considered antipsychotics and their drug classes (FGA or SGA).

Identifying Anti-Dementia Drugs Used to Treat Psychosis in Patients without Dementia

Dementia is highly associated with both psychotic episodes and PD, especially in its later stages.Citation27 To examine the use of anti-dementia drugs to treat psychosis in PD patients only, this analysis was restricted to PD patients without a previous history of dementia diagnosis and/or anti-dementia prescriptions before PD diagnosis, and without dementia diagnosis within 1 year after PD diagnosis (Appendix 1). The first prescription of anti-dementia drugs within 1 year after PD diagnosis was reported. Anti-dementia drugs examined were donepezil, galantamine, memantine, and rivastigmine.

Factors Affecting Use of Antipsychotics in PD Patients

Patient demographics and social variables were obtained from SAIL. These included sex, age at PD diagnosis, year of PD diagnosis, status of social deprivation, and health board geographical location. Other variables included history of comorbidities (before PD diagnosis), the first PD medications prescribed, and previous use of drugs that induce psychosis. Age was categorized into three stages: 40–60 (early onset of PD), 61–80, and 81 years or older. Year of PD diagnosis was grouped to pre-2008 (ie, 2000–2008), and post-2008 (ie, 2009–2016). The year of 2008 was chosen to examine the effect of the FDA warning issued in that year.Citation13 Year of PD diagnosis was treated as a continuous variable when examining use of anti-dementia drugs to treat psychosis. The status of social deprivation was classified into “most deprived” (quintiles 1 and 2), “middle deprived” (quintile 3), and “least deprived” (quintiles 4 and 5), according to the scale of the Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation (WIMD). The seven health boards in Wales were listed in Appendix 3. Comorbidities were extracted from hospital data using the Charlson comorbidity index.Citation28 The comorbidities consisted of acute myocardial infarction, cancer, cerebral vascular accident, congestive heart failure, connective tissue disorder, dementia, diabetes, diabetes complications, liver disease, metastatic cancer, paraplegia, peptic ulcer, peripheral vascular disease, pulmonary disease, renal disease, and severe liver disease. Each comorbidity was treated as a dichotomous variable. The first PD medication prescribed was defined as the first one prescribed to a patient after the PD diagnosis. For antipsychotic users, the first PD medication was required to be initiated before the first antipsychotic prescription. Drugs that induce psychosis included muscle relaxants, antihistamines, antidepressants, cardiovascular medications, antihypertensive medications, analgesics, anticonvulsants, and corticosteroids.Citation29

Statistical Methods

The data were exported and analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25 for Windows. Both descriptive and inferential statistics were used. Multivariate logistic regression was used to test the association between the independent predictors (eg, sex, age, year of PD diagnosis and others) and the outcome (use of antipsychotic or anti-dementia drug to treat psychosis). The Wald test was used to assess the significant overall effect of each independent predictor in the model. A particular predictor was included in the multivariate analysis if the association had a p-value of <0.20. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were obtained from the regression results. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Abiding by the rules of SAIL to preserve patient anonymity, aggregate numbers less than five were excluded from the analysis.

Results

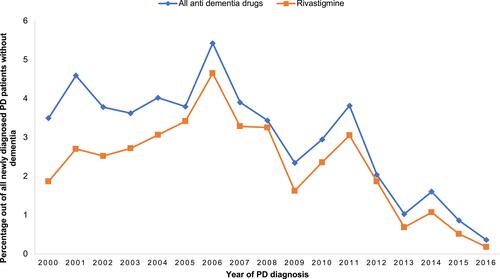

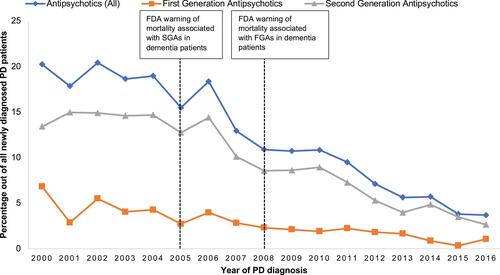

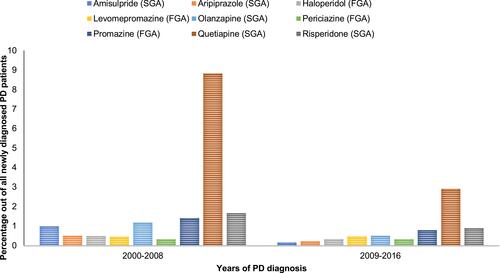

A total of 9142 PD patients were identified after applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, of whom 58.6% were male. depicts the demographic profiles of the newly diagnosed PD patients investigated in the study. The majority (62%) were 61–80 years, with a mean age of 73.7 and a standard deviation of 9.8. The years of PD diagnoses were similar pre- and post-2008 (49.8% and 50.2%, respectively). Most PD patients (82%) used Levodopa as an initial therapy. During the first year of PD diagnosis, 21.8% of the patients developed psychosis, and 55% of them were subsequently prescribed antipsychotics. In general, SGAs were more commonly prescribed (9.3%) to treat psychosis compared to FGAs (2.7%), although the use of both notably decreased across years (). Among antipsychotic users (n = 1095), quetiapine was the most commonly prescribed (49%), followed by risperidone (10.7%), olanzapine (9.3%), and haloperidol (7.1%) (). After excluding PD patients with a previous or current diagnosis of dementia (n = 255), 2.8% of PD patients with a diagnosis of psychosis were prescribed anti-dementia drugs to treat psychosis (). The prescribed anti-dementia drugs were donepezil, galantamine, memantine, and rivastigmine; rivastigmine was most commonly prescribed (76%).

Table 1 Patient Demographics

Figure 1 Trend of new antipsychotics use during the first year of PD diagnosis grouped by drug class.

Figure 2 Trend of new antipsychotics use during the first year of PD diagnosis grouped by drug name.

The first logistic regression model () showed that the use of antipsychotics in newly diagnosed PD patients was significantly lower in the years of 2009–2016 compared to 2000–2008 (OR 0.37, 95% CI 0.32–0.43). Age had a significant impact on antipsychotic prescribing; patients aged 61–80 were highly likely to use antipsychotics compared to those aged 40–60 (OR 1.44, 95% CI 1.11–1.86). Patients with a history of dementia were 3.16 times more likely to use antipsychotics after PD diagnosis (95% CI 2.35–4.24). Comorbidities such as myocardial infarction and peptic ulcer increased the odds of antipsychotic use (OR 1.59, 95% CI 1.15–2.2 and OR 2.27, 95% CI 1.06–4.83, respectively). There was no significant effect of social deprivation status (WIMD scale) on antipsychotic use (see for associated ORs and 95% CIs).

Table 2 Multiple Logistic Regression Examining Potential Factors Affecting the Trend Antipsychotics Use in PD Patients Within the First Year of Their PD Diagnosis

Regarding the use of anti-dementia drugs to treat psychosis in PD patients within the first year of their PD diagnosis, the second logistic regression model () showed different factors compared to the previous model (). For example, although showed a decrease in anti-dementia drug use over years, this decline was not significant in the adjusted regression model (OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.52–1.57). Patients aged >80 years were more likely to use anti-dementia drugs (OR 0.53, 95% CI 0.28–0.98). Further, patients who resided in the least deprived areas (WIMD 4 and 5) were more likely to be prescribed anti-dementia drugs (OR 1.62, 95% CI 1.17–2.24) (see for associated ORs and 95% CIs).

Table 3 Multiple Logistic Regression Examining Potential Factors Affecting the Trend of Anti-Dementia Use to Treat Psychosis in PD Patients Within the First Year of Their PD Diagnosis

Discussion

This study examined antipsychotic use in a large, national sample of patients in Wales who received a diagnosis of PD and who had been followed up for one year after PD diagnosis between 2000 and 2016. A substantial decrease in antipsychotic prescribing patterns was found after the FDA issued its warnings against the use of antipsychotics in dementia patients.Citation13 Although the FDA warning was directed to dementia patients, the prevalence of dementia in PD patients can reach 80%, especially in the later stages of PD.Citation30 Additionally, dementia is strongly associated with psychosis in PD.Citation31 Therefore, it was expected that the FDA warning would decrease the use of antipsychotics in PD patients. The current study provides data to show this decrease, demonstrating a reasonable adherence to national and international guidance.Citation14

Several previous studies estimated that the prevalence of antipsychotic use in PD patients ranged from 0.45% to 18.3%.Citation21,Citation32 The cumulative probability of using antipsychotics after PD diagnosis was found to be 35% after 7 years in a Canadian study,Citation33 and 51% after 6 years in a Taiwanese study.Citation22 However, these studies examined all stages of PD, and none examined antipsychotic use in newly diagnosed PD patients. Psychosis in the early stages of PD is not rare, and symptoms such as minor hallucination could affect 42% of newly diagnosed PD patients.Citation3 Therefore, a novel finding from the current study suggests that 12% of newly diagnosed PD patients were prescribed antipsychotics after being diagnosed with psychosis.

The current study found that more than half of PD patients with psychosis (55%) were prescribed antipsychotics, leaving about 45% of the patients without treatment. This is understandable since the first recommended approach to treating psychosis in PD patients is to reduce the doses of PD medications and then to consider antipsychotic medications if needed,Citation1 however, the data on prescribed doses are not available in the SAIL databank to confirm this explanation. Similar to previous international studies,Citation20–Citation22,Citation32,Citation34,Citation35 the current study found that the majority of antipsychotics prescribed to PD patients were SGAs. Quetiapine in particular constituted almost half of the prescribed antipsychotics, the same pattern found in two previous US studies.Citation15,Citation21 The tendency to prescribe quetiapine and to avoid FGAs in the current study is in line with medical literature that linked FGAs to worsening Parkinson-like motor symptoms, which it is not desirable in PD patients.Citation7 Additionally, among SGAs, quetiapine is more tolerated in PD patients compared to other SGAs.Citation19 Although no clinical trial has confirmed its efficacy and superiority over other SGAs, clinical experience suggests that quetiapine is possibly useful in treating psychosis in PD patients without noticeable side effects that need continuous monitoring.Citation36 It is of note that clozapine—although it is recommended for use in PD psychosisCitation10 was not prescribed to PD patients in the study sample. Two possible reasons for this are the risk of agranulocytosis that accompanies clozapine use, and its requirement for continuous blood monitoring.Citation10 Another reason might be that the UK guidance (NICE guidance) considers clozapine to be the second-line treatment after quetiapine.Citation10 Furthermore, the current study examined only the first use of antipsychotics during the first year after PD diagnosis, which increased the likelihood that the therapy would start with a treatment that requires less monitoring, ie, quetiapine. It is possible that clozapine was initiated in some PD patients in the later stages of PD but due to the lack of data later than 1 year after the initial PD diagnosis, this cannot be confirmed. Among antipsychotics, the current study did not include newer SGAs such as pimavanserin. Pimavanserin was approved by the USFDA in 2016 for treating psychosis in PD patients and it shows good efficacy to treat psychosis without worsening Parkinsonian symptoms in PD patientsCitation37; however, it is not yet approved in the UK.Citation38

Regarding the comorbidities associated with antipsychotic use, the current study found that myocardial infarction and peptic ulcer increased the odds of antipsychotic use in PD patients. Although it has been reported that antipsychotic use could cause myocardial infarction and peptic ulcer,Citation39 no previous study has suggested that the two comorbidities increased the likelihood of antipsychotic use. Whether this is due to a bidirectional relationship between antipsychotics and the two comorbidities, or due to a previous use of antipsychotics that caused comorbidities before PD diagnosis, is not clear. However, the current study excluded from the analysis all newly diagnosed PD patients who used antipsychotics within 1 year prior to PD diagnosis. Nevertheless, more research is needed to determine the nature of such an association.

In contrast to previous literature that linked residing in more deprived areas to an increase in antipsychotic use in the UK general population,Citation40 the current study found no difference between areas ranked as the most deprived relative to areas ranked as deprived in terms of antipsychotic use in PD patients. A possible explanation may be that patients in deprived areas are more likely to present the first symptoms of PD to a primary care provider in later stages of the disease;Citation41 therefore, the provider may avoid prescribing antipsychotics since they worsen PD motor symptoms.

No previous study has examined the prescribing pattern of anti-dementia drugs to treat psychosis in PD patients. The current study found that the use of anti-dementia drugs to treat psychosis in newly diagnosed PD patients was very low (2.8%), and this trend declined across the years of the study. Although there is some evidence that rivastigmine, for example, can reduce hallucination and improve behavioral symptoms in PD patients,Citation18 recent NICE guidelines do not recommend rivastigmine as part of therapy.Citation19 The low prescribing rate of anti-dementia drugs in newly diagnosed patients shown in this study cannot be extrapolated to the later stages of PD due to the high dementia rate in advanced PD patients, which may lead to increased prescribing of rivastigmine to manage both dementia and psychosis.Citation30

In contrast to antipsychotic use, which showed no difference among areas of different deprivation status, anti-dementia drugs were more likely to be used by PD patients who resided in the least deprived areas. This social inequality in access to anti-dementia drugs was seen previously in dementia patients in the UK.Citation42 The current study extended this inequality to PD patients who use these drugs to treat psychosis. Anti-dementia drugs may be less accessible to patients in more deprived areas because these patients have a higher profile of morbidity and mortality, may attend primary care clinics that lack resources, and may not attend their appointments.Citation43 Efforts must be made to address this inequality.

Strengths of the study include the large sample size, robust inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the use of multiple covariates linked to primary care data from different sources in Wales. Limitations include the inability to verify the PD diagnosis, such as confirming the diagnosis by a movement disorders neurologist; however, the diagnosis of other disease was validated in the SAIL data.Citation44 Another limitation was that the SAIL data did not indicate the severity of PD.

Conclusion

This study found a substantial decrease in antipsychotic prescribing patterns after the FDA issued warnings in 2005 and 2008 against the use of antipsychotics, showing a reasonable adherence to national and international prescribing guidance. Continuous and closer monitoring of antipsychotic use is warranted, which must be balanced with the effective and safe use of antipsychotics in PD patients.

Acknowledgments

I acknowledge the help provided by from SAIL team in all stages of the study.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ffytche DH, Creese B, Politis M, et al. The psychosis spectrum in Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13(2):81–95. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2016.200

- Schapira AHV, Chaudhuri KR, Jenner P. Non-motor features of Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017. doi:10.1038/nrn.2017.62

- Pagonabarraga J, Martinez-Horta S, Fernandez de Bobadilla R, et al. Minor hallucinations occur in drug-naive Parkinson’s disease patients, even from the premotor phase. Mov Disord. 2016;31(1):45–52. doi:10.1002/mds.26432

- Obeso JA, Stamelou M, Goetz CG, et al. Past, present, and future of Parkinson’s disease: a special essay on the 200th Anniversary of the Shaking Palsy. Mov Disord. 2017;32(9):1264–1310. doi:10.1002/mds.27115

- Blandini F, Armentero MT. Dopamine receptor agonists for Parkinson’s disease. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2014;23(3):387–410. doi:10.1517/13543784.2014.869209

- Safarpour D, Thibault DP, DeSanto CL, et al. Nursing home and end-of-life care in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2015;85(5):413–419. doi:10.1212/wnl.0000000000001715

- Shirzadi AA, Ghaemi SN. Side effects of atypical antipsychotics: extrapyramidal symptoms and the metabolic syndrome. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2006;14(3):152–164. doi:10.1080/10673220600748486

- Divac N, Prostran M, Jakovcevski I, Cerovac N. Second-generation antipsychotics and extrapyramidal adverse effects. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:656370. doi:10.1155/2014/656370

- Avorn J, Bohn RL, Mogun H, et al. Neuroleptic drug exposure and treatment of parkinsonism in the elderly: a case-control study. Am J Med. 1995;99(1):48–54. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(99)80104-1

- Rogers G, Davies D, Pink J, Cooper P. Parkinson’s disease: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ. 2017;358:j1951. doi:10.1136/bmj.j1951

- Lutz UC, Sirfy A, Wiatr G, et al. Clozapine serum concentrations in dopamimetic psychosis in Parkinson’s disease and related disorders. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;70(12):1471–1476. doi:10.1007/s00228-014-1772-0

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Public Health Advisory. Deaths with antipsychotics in elderly patients with behavioral disturbances. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Government; 2005. Available from: www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/postmarketdrugsafetyinformationforpatientsandproviders/ucm053171.htm. Accessed February 6, 2005.

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Information for healthcare professionals—antipsychotics. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Government; 2008. Available from: www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm124830.htm. Accessed February 6, 2005

- Banerjee S. The use of antipsychotic medication for people with dementia: time for action. 2009.

- Weintraub D, Chiang C, Kim HM, et al. Association of antipsychotic use with mortality risk in patients with Parkinson disease. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73(5):535–541. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.0031

- Marras C, Gruneir A, Wang X, et al. Antipsychotics and mortality in Parkinsonism. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(2):149–158. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e3182051bd6

- de Lau LM, Verbaan D, Marinus J, van Hilten JJ. Survival in Parkinson’s disease. Relation with motor and non-motor features. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014;20(6):613–616. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.02.030

- Rolinski M, Fox C, Maidment I, McShane R. Cholinesterase inhibitors for dementia with Lewy bodies, Parkinson’s disease dementia and cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;3:CD006504. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006504.pub2

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Parkinson’s disease in adults. NICE guideline [NG71]; 2017.

- Herrmann N, Marras C, Fischer HD, Wang X, Anderson GM, Rochon PA. Management of neuropsychiatric symptoms in long-term care residents with Parkinson’s disease: a retrospective cohort study. Drugs Aging. 2013;30(1):19–22. doi:10.1007/s40266-012-0038-8

- Weintraub D, Chen P, Ignacio RV, Mamikonyan E, Kales HC. Patterns and trends in antipsychotic prescribing for Parkinson disease psychosis. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(7):899–904. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2011.139

- Wang MT, Lian PW, Yeh CB, Yen CH, Ma KH, Chan AL. Incidence, prescription patterns, and determinants of antipsychotic use in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2011;26(9):1663–1669. doi:10.1002/mds.23719

- Lyons RA, Jones KH, John G, et al. The SAIL databank: linking multiple health and social care datasets. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2009;9:3. doi:10.1186/1472-6947-9-3

- Robinson D, Schulz E, Brown P, Price C. Updating the read codes: user-interactive maintenance of a dynamic clinical vocabulary. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1997;4(6):465–472. doi:10.1136/jamia.1997.0040465

- Parkinson’s UK. The prevalence and incidence of Parkinson’s in the UK. Parkinson’s UK; 2017. Available from: https://www.parkinsons.org.uk/sites/default/files/2018-01/Prevalence%20%20Incidence%20Report%20Latest_Public_2.pdf. Accessed January, 25, 2018.

- Rochon PA, Stukel TA, Sykora K, et al. Atypical antipsychotics and parkinsonism. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(16):1882–1888. doi:10.1001/archinte.165.16.1882

- Leroi I, Voulgari A, Breitner JC, Lyketsos CG. The epidemiology of psychosis in dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11(1):83–91. doi:10.1097/00019442-200301000-00011

- Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(11):1245–1251. doi:10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5

- Mauri MC, Paletta S, Di Pace C. Hallucinations in the substance-induced psychosis. In: Hallucinations in Psychoses and Affective Disorders. Cham: Springer; 2018:57–83.

- Aarsland D, Andersen K, Larsen JP, Lolk A, Kragh-Sorensen P. Prevalence and characteristics of dementia in Parkinson disease: an 8-year prospective study. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(3):387–392. doi:10.1001/archneur.60.3.387

- Aarsland D, Larsen JP, Lim NG, et al. Range of neuropsychiatric disturbances in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;67(4):492–496. doi:10.1136/jnnp.67.4.492

- Marras C, Austin PC, Bronskill SE, Diong C, Rochon PA. Antipsychotic drug dispensing in older adults with Parkinsonism. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26(12):1244–1257. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2018.08.003

- Marras C, Kopp A, Qiu F, et al. Antipsychotic use in older adults with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2007;22(3):319–323. doi:10.1002/mds.21192

- Rigby HB, Rehan S, Hill-Taylor B, Matheson K, Sketris I. Antipsychotic prescribing practices in those with Parkinsonism: adherence to guidelines. Can J Neurol Sci. 2017;44(5):603–606. doi:10.1017/cjn.2017.36

- Vanacore N, Bianchi C, Da Cas R, Rossi M. Use of antiparkinsonian drugs in the Umbria region. Neurol Sci. 2003;24(3):221–222. doi:10.1007/s10072-003-0140-0

- Seppi K, Ray Chaudhuri K, Coelho M, et al. Update on treatments for nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease—an evidence‐based medicine review. Mov Disorders. 2019;34(2):180–198. doi:10.1002/mds.27602

- Patel RS, Bhela J, Tahir M, Pisati SR, Hossain S. Pimavanserin in Parkinson’s disease-induced psychosis: a literature review. Cureus. 2019;11(7):e5257. doi:10.7759/cureus.5257

- Taylor C, Marsh-Davies A, Skelly R, Archibald N, Jackson S. Setting up a clozapine service for Parkinson’s psychosis. BJPsych Adv. 2021;1–9. doi:10.1192/bja.2021.24

- Cotton CC, Farkas DK, Foskett N, et al. Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding and gastroduodenal ulcers in persons with schizophrenia: a Danish cohort study. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2019;10(2):e00005. doi:10.14309/ctg.0000000000000005

- Marston L, Nazareth I, Petersen I, Walters K, Osborn DP. Prescribing of antipsychotics in UK primary care: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2014;4(12):e006135. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006135

- Orayj K, Akbari A, Lacey A, Smith M, Pickrell O, Lane EL. Factors affecting the choice of first-line therapy in Parkinson’s disease patients in Wales: a population-based study. Saudi Pharm J. 2021;29(2):206–212. doi:10.1016/j.jsps.2021.01.004

- Cooper C, Lodwick R, Walters K, et al. Observational cohort study: deprivation and access to anti-dementia drugs in the UK. Age Ageing. 2016;45(1):148–154. doi:10.1093/ageing/afv154

- Mercer SW, Watt GC. The inverse care law: clinical primary care encounters in deprived and affluent areas of Scotland. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(6):503–510. doi:10.1370/afm.778

- Fonferko-Shadrach B, Lacey AS, White CP, et al. Validating epilepsy diagnoses in routinely collected data. Seizure. 2017;52:195–198. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2017.10.008