Abstract

Menopausal symptoms (eg, hot flushes and vaginal symptoms) are common, often bothersome, and can adversely impact women’s sexual functioning, relationships, and quality of life. Estrogen–progestin therapy was previously considered the standard care for hormone therapy (HT) for managing these symptoms in nonhysterectomized women, but has a number of safety and tolerability concerns (eg, breast cancer, stroke, pulmonary embolism, breast pain/tenderness, and vaginal bleeding) and its use has declined dramatically in the past decade since the release of the Women’s Health Initiative trial results. Conjugated estrogens paired with bazedoxifene (CE/BZA) represent a newer progestin-free alternative to traditional HT for nonhysterectomized women. CE/BZA has demonstrated efficacy in reducing the frequency and severity of vasomotor symptoms and preventing loss of bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. CE/BZA provides an acceptable level of protection against endometrial hyperplasia and does not increase mammographic breast density. Compared with traditional estrogen–progestin therapy, it is associated with lower rates of breast pain/tenderness and vaginal bleeding. Patient-reported outcomes indicate that CE/BZA improves menopause-specific quality of life, sleep, some measures of sexual function (especially ease of lubrication), and treatment satisfaction. This review looks at the rationale for selection and combination of CE with BZA at the dose ratio in the approved product and provides a detailed look at the efficacy, safety, tolerability, and patient-reported outcomes from the five Phase III trials. Patient considerations in the choice between CE/BZA and traditional HT (eg, tolerability, individual symptoms, and preferences for route of administration) are also considered.

Video abstract

Point your SmartPhone at the code above. If you have a QR code reader the video abstract will appear. Or use:

Introduction

Vasomotor symptoms (VMSs) of menopause occur in ~55%–90% of women,Citation1–Citation5 and ~70% of women with these hot flushes and night sweats find them bothersome.Citation6 In addition, ~40%–70% of postmenopausal women experience vaginal/sexual symptoms (eg, discomfort, dryness, soreness, itching, burning, or pain on contact, dyspareunia, diminished libido, and avoidance of intimacy);Citation3,Citation5 three-fourths of these women say vaginal symptoms have a negative impact on their lives.Citation3 Life expectancy is increasing,Citation7 and data suggest, for some women, menopausal symptoms may last many more years than previously suspected.Citation1,Citation4,Citation5,Citation8

This review of current and emerging pharmacologic therapies for bothersome menopausal symptoms focuses on efficacy, safety, and patient considerations regarding use of conjugated estrogens/bazedoxifene (CE/BZA). CE/BZA is a relatively new treatment for women with a uterus who experience moderate-to-severe VMSs; CE/BZA also helps preserve bone mineral density (BMD). CE/BZA provides a progestin-free alternative to traditional estrogen plus progestin therapy for women with a uterus and seeking treatment for menopausal symptoms. As reviewed in this article, by combining estrogens with a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) instead of a progestin, CE/BZA not only offers endometrial protection but may also avoid breast stimulation and have fewer adverse events typically associated with progestin use (eg, breast pain and vaginal bleeding).

Current and emerging management of menopausal symptoms

Oral hormone therapy

According to numerous international guidelines and expert consensus statements, oral hormone therapy (HT) is safe and effective to start in younger postmenopausal women (ie, those <60 years of age or those whose last menstrual period was ≤10 years ago) who have bothersome menopausal symptoms and/or require osteoporosis prevention.Citation9–Citation14 The optimal duration of HT use is unknown, but the lowest effective dose should be used for the shortest time needed for symptom control;Citation10,Citation11 duration should also be consistent with the patient’s treatment goals. Given the long duration of menopausal symptoms, it may be appropriate to extend the duration of HT use beyond 5 years for some women who continue to require symptom reliefCitation10,Citation11,Citation13–Citation16 and osteoporosis prevention, particularly if they are not candidates for other osteoporosis therapies.Citation9 The decision of when to terminate HT use should be based on an individualized assessment of the risks and benefits, and should include patient counseling regarding risks of breast cancer and stroke.Citation15

Much of what is known from clinical trials about the risk–benefit profile of HT for the prevention of chronic disease has been derived from the two large (N=27,347), randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) trials.Citation17–Citation19 These trials were conducted in postmenopausal women 50–79 years of age (mean age, ~63–64 years) who were not required to have menopausal symptoms.Citation17–Citation19 (In fact, at baseline, only 12.7% of women randomized to conjugated estrogens/medroxyprogesterone acetate [CE/MPA] and 12.2% of those in the placebo group had moderate or severe VSMs.Citation20).

Both the study of CE alone in hysterectomized women and the study of CE/MPA in nonhysterectomized women failed to demonstrate a reduction in coronary heart disease (CHD) in their overall population, which was the primary efficacy end point.Citation17,Citation18 The CE/MPA trial was terminated early by its data safety and monitoring board based on the lack of cardioprotection (and possible increase in CHD) coupled with increased risks of breast cancer, stroke, and pulmonary embolism.Citation18 The trial of CE alone was subsequently terminated early by the National Institutes of Health based on the lack of cardioprotection and increased risk of stroke, despite the fact that none of the predetermined stopping points had been met.Citation17 Although CE/MPA was associated with increased risks of breast cancer and related mortality,Citation21,Citation22 no such increases were found in the trial of CE alone; in fact, there was a possible protective effect that became statistically significant in the postintervention period.Citation19,Citation23 Thus, CE alone from a relative risk perspective appeared to be safer than CE/MPA with regard to risks of breast cancer and CHD.Citation19 Furthermore, progestin-related adverse effects (eg, breast tenderness and vaginal bleeding) are often poorly tolerated and may contribute to poor compliance and discontinuation of HT.Citation24,Citation25 However, omitting the progestin and giving CE alone is not an option for nonhysterectomized women because unopposed estrogens can result in hyperplasia and other unwanted effects on the endometrium in a menopausal woman.Citation13 The inclusion of a progestin has been clearly demonstrated to counter these effects.Citation12,Citation13

Benefits of HT identified in the WHI trials include significant reductions in osteoporotic fractures,Citation17–Citation19 self-reported VMSs, diabetes, joint pain, and (for CE/MPA only) colorectal cancer.Citation19 It should be noted that findings from the WHI trials, both positive and negative, apply specifically to CE and CE/MPA; it is unknown whether similar results would be obtained with other HT formulations.

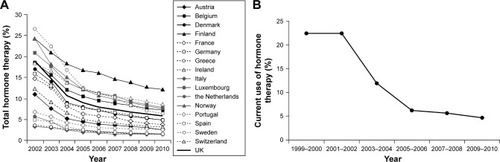

Rates of HT use have declined dramatically since the WHI trials, such that HT is now used by <10% of postmenopausal women in most developed countries in Europe () and the USA ().Citation26,Citation27 Given the high prevalence of bothersome symptoms,Citation1,Citation6 low rates of HT use suggest under-treatment of menopausal symptoms. Indeed, a survey of postmenopausal women in the USA, conducted by the Endocrine Society, revealed that nearly three-fourths of women with menopausal symptoms had not been treated for them.Citation28 Untreated VMSs are associated with greater absenteeism and health care costs, as well as impaired quality of life and personal relationships.Citation29,Citation30 A recent survey of Australian women determined that moderate-to-severe VMSs have an adverse impact on psychological well-being that is comparable to that of housing insecurity and greater than that of obesity or being a caregiver for a family member with special needs.Citation31 Vaginal discomfort related to menopause can interfere with libido, intimate relationships, self-esteem, and quality of life.Citation3,Citation32,Citation33

Figure 1 Changes in estimated proportion of women aged 45–69 years using menopausal hormone therapy in 17 European countries from 2002 to 2010 (A). Changes in estimated proportion of women aged ≥40 years reporting current use of oral postmenopausal hormones from 1999 to 2010 in the USA (B).

The decline in use of traditional HT has been accompanied by increasing popularity of custom-compounded bioidentical HT, which is used by an estimated 1–2.5 million US women annually.Citation34 This trend is troublesome given the lack of evidence supporting the efficacy and safety of compounded bioidentical HT and the potential for additional risks due to variable purity, potency, and quality.Citation35

Benefits and safety of HT for treatment of menopausal symptoms in younger women shortly after menopause were not addressed by the WHI results. Reanalyses of the WHI trials suggested lower risks of CHD, stroke, and a global index of events (ie, CHD, stroke, pulmonary embolism, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, endometrial cancer, hip fracture, or all-cause mortality) among women in their 50s and/or women closer to menopause compared with older women and women who have been postmenopausal longer.Citation36 For example, in the trial of CE alone, although not statistically significant, the hazard ratio (95% confidence interval [CI]) for CHD was 0.63 (0.36–1.09) in women 50–59 years indicating a possible protective effect, whereas it was 0.94 (0.71–1.24) in women aged 60–69 years and 1.13 (0.82–1.54) in women 70–79 years of age.Citation36 Breast cancer risk with CE/MPA, however, was not lower in this younger group.Citation22

Other forms of hormonal therapy

HT formulations with vaginal or transdermal routes of administration are also available. Selection of the route of administration should take into account the individual woman’s symptoms and preferences. Vaginal estrogens are recommended if the only bothersome menopausal symptoms are genitourinary in nature.Citation11,Citation13,Citation37 This is likely to be a small proportion of younger postmenopausal women because a majority of such women have VMSs.Citation2

It has been hypothesized based on observational data that transdermal estrogens’ avoidance of first-pass hepatic metabolism may result in reduced risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), and that lower doses used with transdermal administration may also result in lower rates of dose-related adverse effects (eg, breast tenderness and vaginal bleeding).Citation38 However, most of these safety and tolerability outcomes have not been compared in head-to-head randomized trials of transdermal versus oral HT, so these claims are as yet unproven.

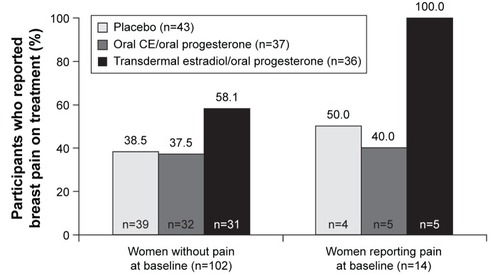

In fact, in a subset analysis of the Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS), one of the few comparative trials, the authors concluded that there was no significant difference between transdermal 17-β-estradiol 50 μg/d with oral micronized progesterone 200 mg/d, oral CE 0.45 mg/d with oral micronized progesterone 200 mg/d, or placebo with regard to the occurrence or the severity of breast pain.Citation39 Although the incidence of breast pain (collected at baseline and yearly with the Mayo Clinic Breast Pain Questionnaire) before and during treatment was not significantly different across the treatment groups (P=0.78 before treatment; P=0.18 during treatment), a numerically higher proportion of women developed new-onset breast pain during treatment in the transdermal group (18 out of 31 women without baseline pain [58%]) than in the oral HT group (12 out of 32 women without baseline pain [38%]) or the placebo group (15 out of 39 women without baseline pain [38%]) ().Citation39 The transdermal and oral formulations both had neutral effects on endothelial dysfunction (measured via pulse volume digital tonometry) and, compared with placebo, both significantly improved VMSs to a similar extent.Citation40

Figure 2 Incidence of breast pain during treatment with transdermal estradiol/oral micronized progesterone, oral CE/oral micronized progesterone, or placebo in women with and without baseline pain in KEEPS.

Abbreviations: CE, conjugated estrogens; KEEPS, Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study.

The KEEPS study was not designed to evaluate differences between the treatments with regard to VTE rates. However, KEEPS did evaluate effects on platelet count and function (as a marker of thrombotic risk) in a subgroup of 117 women and found that neither formulation had a significant effect on general platelet characteristics, including platelet count, spontaneous micro-aggregation (a test of platelet sensitivity), or expression of surface receptors for P-selectin or fibrinogen.Citation41 Both oral and transdermal estrogens had comparable effects on platelet proteins, and transdermal estrogens (but not oral estrogens) increased the number of tissue factor-positive microvesicles and platelet-derived microvesicles, indicative of cellular activation and a procoagulant environment.Citation41

Ospemifene, a SERM, is an oral therapy indicated for dyspareunia.Citation42 In two 12-week Phase III clinical trials, ospemifene at the approved dose of 60 mg/d significantly improved the vaginal maturation index (P<0.001) and vaginal pH (P<0.001) and reduced dyspareunia (P<0.05) compared with placebo in postmenopausal women with vulvar-vaginal atrophy,Citation43,Citation44 which is now considered a component of the genitourinary syndrome of menopause.Citation45 Hot flushes were an adverse event,Citation43,Citation44,Citation46 typical of SERMs,Citation47–Citation49 so ospemifene may not be an ideal choice for women who are already experiencing bothersome VMSs. Endometrial effects of ospemifene were reported to be negligibleCitation43 or not clinically meaningful,Citation44 although minor increases in endometrial thickness were observed, along with a couple of cases of active endometrial proliferation. There were no cases of endometrial hyperplasia or carcinoma observed in the core studies or a 40-week extension of the first trial.Citation43,Citation46

Finally, as noted earlier, CE/BZA is the first successfully developed progestin-free, estrogen-based therapy for nonhysterectomized women consisting of a combination of estrogens and a SERM. CE/BZA is reviewed in detail beginning on the next page.

Nonhormonal therapies

The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor paroxetine is the first nonhormonal prescription therapy approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of moderate-to-severe menopausal VMSs.Citation50 In two randomized Phase III clinical trials, paroxetine reduced moderate-to-severe VMSs by ~0.9/d and 1.4/d relative to placebo at week 12 (P<0.01 and P=0.0001, respectively).Citation51 As the average daily number of hot flushes at baseline was 11.8 and 10.8, this amounts to a 7.6% and 13.0% reduction in hot flush frequency for paroxetine relative to placebo. VMS severity was also significantly reduced at week 12 in one study (P<0.05).Citation51 Paroxetine did not adversely affect weight or sexual function.Citation52 No comparative data are available, but the magnitude of effect paroxetine has on VMSs appears to be less than what is typically seen with HT. Paroxetine has no favorable bone effects (unlike estrogens), and despite the low dose (7.5 mg/d) used for this indication, it may have adverse effects characteristic of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (eg, fatigue and somnolence).Citation50 Thus, paroxetine should be considered an alternative for women who are not candidates for HT.

The serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor desvenlafaxine is approved for treatment of menopausal symptoms in Mexico, the Philippines, and Thailand, but not the USA or most of Europe. In a randomized controlled trial, desvenlafaxine 100 mg/d reduced the frequency of moderate-to-severe hot flushes by 2–3/d relative to placebo (P<0.001), and also significantly reduced hot flush severity (P<0.01); these effects were well maintained for 12 months.Citation53

Emerging treatments

A number of investigational therapies are in late-stage clinical trials. TX-004HR is a vaginal estradiol suppository that is currently in Phase III development.Citation54 TX-001HR is an oral HT that combines 17-β-estradiol and progesterone into a single peanut-oil-free capsule, whereas these hormones are currently available only separately or through pharmacy compounding.Citation55,Citation56 Pharmacokinetic results show that the bioavailability of estradiol and progesterone with the new combination product is similar to that of commercially available formulations of the separate components.Citation56 A Phase III trial of TX-001HR is ongoing.Citation55,Citation57

Nonhormonal psychotropic therapies (eg, escitalopram,Citation58 sertraline,Citation59 venlafaxine,Citation60 and gastroretentive gabapentinCitation61) have shown modest reductions in hot flushes in clinical studies of postmenopausal women. However, with the exception of gastroretentive gabapentin, they generally have not been studied in large populations of women with at least seven moderate-to-severe hot flushes per day, or 50/wk, as required by the Food and Drug Administration.

Rationale for development of CE/BZA

In an attempt to develop a safe, well-tolerated, progestin-free option for nonhysterectomized women, it was hypothesized that combining estrogens with a SERM might retain beneficial estrogenic effects on VMSs and bone while blocking the known estrogenic effects of estrogens on the endometrium and breast tissue.Citation62,Citation63

The combination CE/BZA has proven uniquely suitable for development. CE has a long history of use and has been well studied. At a dose of 0.625 mg/d, CE was extensively investigated in the WHI trials because it was the most commonly used estrogen formulation.Citation19 Although estradiol is sometimes touted as a more natural or bioidentical hormone, it is unclear whether there is an actual advantage to one estrogen formulation over another. Observational studies largely report little to no statistically significant difference in their relative effects on VTE, CHD, and stroke risk,Citation64–Citation66 and no randomized comparative trials with adequate power to evaluate these endpoints have been conducted. The KEEPS study, described earlier, is the only direct comparison of their relative safety.

BZA is a unique SERM in that it degrades the estrogen receptors in breast and endometrial tissue, similar to fulvestrant.Citation67–Citation72 Preclinical investigations showed that BZA countered the stimulating effects of estrogens in the endometrium and breast when they were coadministered, whereas other SERMs provided less protection against stimulation of these tissues.Citation67,Citation68,Citation70,Citation71,Citation73,Citation74 In fact, a clinical trial of 17-β-estradiol/raloxifene found this combination to result in significant increases in endometrial thickness; in addition, among 91 women who underwent postbaseline endometrial biopsy, cases of endometrial proliferation (estradiol/raloxifene: n=7; raloxifene alone: n=3) and hyperplasia (estradiol/raloxifene: n=2; raloxifene alone: n=0) were found.Citation75

After selection of CE and BZA as the best combination for development, it was necessary to identify the optimal dose ratio that would allow for both endometrial protection and therapeutic efficacy. Based on results of Phase II and III dose-finding studies,Citation76–Citation78 combinations of BZA 20 mg with either CE 0.45 mg or 0.625 mg were determined to best achieve this balance. A series of Phase III trials named the Selective estrogens, Menopause, And Response to Therapy (SMART) trials provide data on the efficacy and safety of these two doses of CE/BZA.

Efficacy of CE/BZA in the SMART trials

The first two SMART trials, SMART-1 and SMART-2, demonstrated significant reductions in hot flush frequency and severity in generally healthy postmenopausal women who had at least seven moderate or severe hot flushes per day or 50/wk at baseline.Citation78,Citation79 In these two trials, CE 0.45 mg/BZA 20 mg and CE 0.625 mg/BZA 20 mg reduced the mean number of moderate-to-severe hot flushes by ~8–9/d at 12 weeks of treatment compared with being reduced bŷ2.5 and 5 in the placebo groups of SMART-1 and SMART-2, respectively (all P<0.001 vs placebo); improvements were sustained throughout 2 years of treatment in SMART-1.Citation78,Citation79 (It should be noted that placebo response rates are typically high [eg, 52% at week 12 in SMART-2Citation79] and may be sustained in treatment of menopausal hot flushes.)Citation80 Similarly, in SMART-1 and SMART-2, respectively, the mean daily hot flush severity rating (1= mild, 2= moderate, and 3= severe) decreased by 1.0 and 0.9 in the CE 0.45 mg/BZA 20 mg arms and 1.1 and 1.2 points in the CE 0.625 mg/BZA 20 mg arms compared with reductions of 0.21 and 0.26 in the placebo arms (all P<0.001 vs placebo) (data on file).Citation78,Citation79 A post hoc analysis of these two trials confirmed that women with both <5 and ≥5 years since menopause achieved significant reductions in hot flush frequency and severity.Citation81

CE/BZA (CE 0.45 mg/BZA 20 mg; Duavee®) is approved for the prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis in the USA and Korea. CE/BZA was shown to reduce bone loss in SMART-1, SMART-4, and SMART-5, whereas patients in the placebo groups lost BMD; CE 0.45 mg/BZA 20 mg and CE 0.625 mg/BZA 20 mg were associated with gains in nearly all BMD outcomes, albeit more modest ones compared with CE/MPA ().Citation82–Citation84 CE/BZA also significantly reduced bone turnover compared with placebo based on changes in serum levels of osteocalcin and C-telopeptide.Citation82–Citation84

Table 1 Effects of CE/BZA on BMD at month 12 in SMART-1,Table Footnote& SMART-4,Table Footnote# and SMART-5Table Footnote$ (data on file)

CE/BZA has not been approved for treatment of vulvar-vaginal symptoms of menopause. However, women taking CE/BZA for other indications may experience some benefits with regard to vaginal health. The SMART-3 trial enrolled postmenopausal women with <5% superficial cells on vaginal cytological smear; a vaginal pH >5; and vaginal dryness, itching/irritation, or pain with sexual intercourse were their most bothersome symptom.Citation85 At 12 weeks, both doses significantly increased superficial cells, decreased parabasal cells, alleviated vaginal dryness, and improved self-reported sexual function, especially ease of lubrication.Citation85,Citation86 The higher dose (which is not commercially available) also significantly decreased vaginal pH and improved the most bothersome vaginal symptom.Citation85

Safety of CE/BZA in the SMART trials

Endometrial safety

CE/BZA’s effect on the risk of endometrial hyperplasia at 12 months was evaluated as a primary end point of SMART-1 and SMART-5.Citation77,Citation84 Without a progestin, CE 0.45 mg/BZA 20 mg and CE 0.625 mg/BZA 20 mg were associated with a <1% incidence of hyperplasia with an upper limit of the 95% CI <2%, which was similar to placebo.Citation77,Citation84 This low rate of endometrial hyperplasia meets the US and European Union regulatory requirements for endometrial safety.Citation87,Citation88 Of note, CE/BZA formulations containing only 10 mg of BZA in SMART-1 and a formulation of CE 0.625 mg/BZA 20 mg used only in SMART-4 that was found to have reduced BZA bioavailability were associated with potentially inadequate endometrial protection, which attests to the importance of utilizing the currently approved combination of CE/BZA to ensure that the optimal dose ratio is maintained.Citation77,Citation83 BZA is believed to block estrogen-stimulated proliferation in the endometrium by inhibiting estrogen-mediated expression of proliferative genes while maintaining expression of antiproliferative genes;Citation89 this differs from progestins, which counter estrogenic activity in the endometrium by inducing epithelial differentiation as well as downregulation of estrogen receptors.Citation90

In a pooled analysis of gynecologic safety data from all five SMART trials,Citation91 there was only one case of endometrial cancer, which occurred in a woman taking CE 0.45 mg/BZA 20 mg. The incidence rate for endometrial cancer among women taking CE 0.45 mg/BZA 20 mg was determined to be 0.4 per 1,000 woman-years (95% CI, 0.0–2.4) with a relative risk compared with placebo of 0.9 (95% CI, 0.2–4.8). (A relative risk of 1 would indicate equivalent risk between the two treatments, whereas a relative risk <1 suggests a protective effect and a relative risk >1 suggests an association with increased risk).

Breast safety

Effects of any menopausal hormonal therapy on breast safety must be carefully evaluated. CE and BZA each separately have demonstrated good breast safety in clinical trials. In the WHI trial, CE alone in hysterectomized women did not adversely affect the breast; in fact, it was associated with a reduction in breast cancer incidence and related mortality that persisted even after discontinuation.Citation23 In a 7-year clinical trial of postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, BZA alone had a neutral effect on the breast, with a low breast cancer incidence and breast stimulation similar to that of placebo.Citation92

CE/BZA did not significantly affect the percentage of dense breast tissue on mammography compared with placebo in substudies of SMART-1 and SMART-5.Citation93,Citation94 In contrast, CE/MPA (an active comparator in SMART-5) did significantly (P<0.001) increase breast density compared with placebo,Citation94 as it also did in the WHI trial.Citation95 These findings are potentially clinically relevant because higher breast density is associated with reduced ability to detect breast cancer on mammography and may be an independent risk factor for breast cancer.Citation96–Citation98

In a pooled analysis of all five SMART trials,Citation91 the incidence of breast cancer was 0.3% with CE 0.45 mg/BZA 20 mg, 0.0% with CE 0.625 mg/BZA 20 mg, and 0.2% with placebo. The incidence rate per 1,000 woman-years was estimated to be 1.0 (95% CI, 0.0–3.2), 0.0 (95% CI, 0.0–1.5), and 1.4 (95% CI, 0.0–4.2), respectively. Relative risk of breast cancer with CE 0.45 mg/BZA 20 mg compared with placebo was 1.1 (95% CI, 0.3–3.8). The longest SMART trials were 2 years, so longer term safety, including breast cancer risk, remains to be confirmed. CE alone was given to hysterectomized women in the WHI trial for a median of ~6 years, and in another study BZA alone was given to women with postmenopausal osteoporosis for up to 7 years, both without evidence of an increase in breast cancer incidence.Citation23,Citation99 CE/BZA has not been studied in women at high risk for breast cancer.

Thromboembolic, cerebrovascular, and cardiovascular safety

An increased risk of VTE has been reported in users of estrogens as well as users of clinically available SERMS, and this association has been independently found with CE and BZA. In the WHI trial, CE alone was associated with an increased risk of deep vein thrombosis (hazard ratio [HR] 1.48, 95% CI, 1.06–2.07) and pulmonary embolism, although the latter did not achieve statistical significance (HR 1.35, 95% CI, 0.89–2.05).Citation19 In postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, BZA 20 mg was associated with a statistically significant increase in the risk of deep vein thrombosis over 7 years (HR 3.38, 95% CI, 1.01–11.39); pulmonary embolism occurred in 2% of both the BZA and placebo groups.Citation92

When CE and BZA are combined, the risk does not appear to be additive.Citation100 In a pooled analysis of the five SMART trials, the incidence of VTE was 0.2% in the CE 0.45 mg/BZA 20 mg group, 0.0% in the CE 0.625 mg/BZA 20 mg group, and 0.1% in the placebo group, and all of the VTEs were deep vein thromboses.Citation100 In the CE 0.45 mg/BZA 20 mg group, the rate per 1,000 woman-years was 0.3 (95% CI, 0.0–2.0) and the relative risk versus placebo was 0.9 (0.2–4.1).Citation100 Given the low number of VTE events in the SMART trials and the incomplete understanding as to the mechanism by which estrogens and SERMs may contribute to VTE risk, the true risk of VTE with CE/BZA remains unknown. Because the increased risk of VTE associated with CE has been shown to occur early, particularly in the first 2 years of treatment, with modest increases thereafter,Citation101 the low rate of VTE in the 2-year SMART-1 trial (relative risk of VTE for CE/BZA vs placebo: 0.48 [95% CI, 0.05–4.66]) is reassuring.Citation78

Stroke occurred in one SMART trial participant treated with CE 0.45 mg/BZA 20 mg (0.06%) and one treated with CE 0.625 mg/BZA 20 mg (0.06%) compared with none in the placebo group.Citation100 The rate per 1,000 woman-years was 0.4 (95% CI, 0.0–2.4) and 0.2 (95% CI, 0.0–1.9) for the approved dose and higher dose of CE/BZA, respectively, and for both doses, the relative risk versus placebo was 0.9 (95% CI, 0.2–4.8).Citation100 As with VTE, the low number of events prohibits definitive conclusions regarding the effect of CE/BZA on stroke risk.

In the pooled analysis of the SMART trials, the rate of any CHD event was 0.3% with either dose of CE/BZA compared with 0.2% in the placebo group, and the rate of myocardial infarction was 0.2% for both CE 0.45 mg/BZA 20 mg and placebo and 0.1% with CE 0.625 mg/BZA 20 mg.Citation100 The rate of any CHD event per 1,000 woman-years was 2.6 (95% CI, 0.0–5.6) with CE 0.45 mg/BZA 20 mg, 1.4 (95% CI, 0.0–3.9) with CE 0.625 mg/BZA 20 mg, and 2.0 (95% CI, 0.0–5.2) with placebo.Citation100 The relative risk versus placebo was 0.9 (95% CI, 0.3–2.9) for the approved dose and 1.0 (95% CI, 0.3–3.1) for the higher dose.Citation100 A pooled analysis of 12- and 24-month data from the three longest trials (SMART-1, SMART-4, and SMART-5) reported that CE/BZA significantly (P<0.001) decreased total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and increased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides compared with placebo – a pattern that is consistent with the effects of traditional HT.Citation102

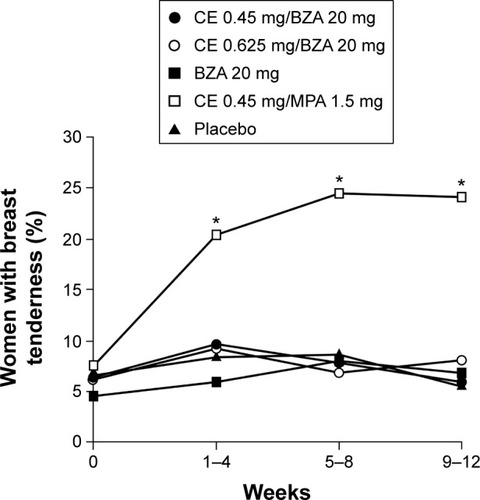

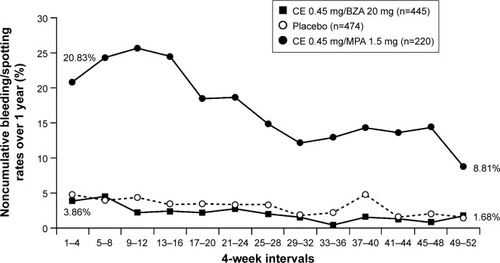

Patient considerations: tolerability of CE/BZA versus other HT

Breast pain/tenderness and vaginal bleeding are common complaints of women using traditional HT. Based on data from the WHI, users of HT are more than four times as likely to experience breast tenderness or vaginal bleeding compared with nonusers.Citation24 In contrast, in SMART-1 and SMART-5, the incidence of breast pain/tenderness with CE/BZA was comparable to placebo, whereas significantly (P<0.001) higher rates of breast tenderness were observed with CE/MPA than CE/BZA in SMART-5 ().Citation78,Citation84,Citation94 Similarly, in SMART-1 and SMART-5,Citation84,Citation103 CE/BZA was associated with high rates of amenorrhea and low rates of bleeding/spotting, similar to placebo, whereas bleeding/spotting rates were significantly (P<0.001) higher with CE/MPA than CE/BZA in SMART-5 ().Citation104 These adverse events may be more than just nuisance effects. Breast pain/tenderness has been reported to be associated with an increase in breast density on mammographyCitation95 as well as increased risk of breast cancer.Citation105 Breakthrough bleeding is not only inconvenient but can also lead to endometrial sonograms, biopsies, and hysteroscopies, which result in unnecessary anxiety and costs.

Figure 3 Percentage of women reporting ≥1 day of breast tenderness in daily diaries during 4-week intervals through 12 weeks in SMART-5.

Abbreviations: SMART, Selective estrogens, Menopause, And Response to Therapy; CE, conjugated estrogens; MPA, medroxyprogesterone acetate; BZA, bazedoxifene.

Figure 4 Bleeding/spotting rates over 1 year of treatment with CE/BZA compared to CE/MPA in SMART-5.Citation104

Abbreviations: CE, conjugated estrogens; BZA, bazedoxifene; MPA, medroxyprogesterone acetate; SMART, Selective estrogens, Menopause, And Response to Therapy.

In some studies, progestin-based therapies have also been associated with mood symptoms (eg, depression and anxiety). In a randomized, placebo-controlled trial, CE/MPA was associated with a significant (P=0.01) increase in depression in women who had not undergone hysterectomy, based on daily ratings on the Prospective Record of the Impact and Severity of Menstrual Symptoms calendar (though depressive symptoms were mostly considered mild and not troublesome); no such increase was found among hysterectomized women taking CE alone.Citation106 A study using data from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey V found an increased risk of depression among women who initiated HT before age 48 (vs never users; OR 3.86, 95% CI, 2.10–7.09), and the odds of depression increased with longer HT use (P-trend <0.001).Citation107 Not all studies of HT have shown adverse effects on mood, however. In the WHI trial, CE/MPA had a neutral effect on mood swings compared with placebo,Citation24 and in the randomized, placebo-controlled KEEPS-Cognitive and Affective Study (KEEPS-Cog) of perimenopausal and early postmenopausal women, oral CE with cyclical oral micronized progesterone was found to significantly reduce tension-anxiety (small to medium effect size) and depression-dejection scores (medium effect size) on the Profile of Mood States compared with placebo.Citation108 These benefits with regard to mood were not observed with transdermal estradiol plus oral micronized progesterone, though the formulations provided comparable benefits with regard to reduction of VMSs.Citation108

Menopausal hormonal therapy may also adversely affect insulin sensitivity. In a randomized, placebo-controlled trial, CE/MPA reduced insulin sensitivity by 17% without altering body composition, fat distribution, or body weight.Citation109 The effect persisted throughout the 2 years of treatment but was reversible after treatment discontinuation.Citation109 Other preclinical and clinical studies suggest that estrogens increase insulin sensitivity, but this effect is countered by progestogens, which are associated with hyperinsulinemia and decreased insulin sensitivity or glucose tolerance.Citation110–Citation112 Effects of CE/BZA on mood and insulin sensitivity have not been reported; however, women who experience these effects while taking estrogen/progestin therapy may wish to consider a trial of CE/BZA as an alternative, progestin-free option.

Patient-specific outcomes

Data from the SMART trials also indicate that CE/BZA improves various patient-reported outcomes, including menopause-specific quality of life, sleep, and treatment satisfaction.

Menopause-specific quality of life was evaluated in SMART-1, -2, -3, and -5 using the Menopause-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire.Citation113 Although the studies enrolled different populations (generally healthy women, women with moderate-to-severe VMSs, and women with vulvar-vaginal symptoms), both doses of CE/BZA significantly improved overall Menopause-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire scores and vasomotor function subscale scores in all four studies at virtually all time points through 24 months.Citation113 In the SMART trial participants with VMSs at baseline (SMART-2 and SMART-5), the improvements in vasomotor functioning with CE 0.45 mg/BZA 20 mg versus placebo exceeded previously established, clinically important differences.Citation113 Both doses of CE/BZA improved the sexual functioning domain score in SMART-1 and SMART-3, and the higher dose also improved sexual functioning scores in SMART-2 and SMART-5.Citation113 Women in SMART-3, who had vulvar-vaginal symptoms at baseline, experienced the greatest improvements in sexual functioning, which were statistically significant, although they did not exceed clinically important differences.Citation113

The effects of CE/BZA on sleep were evaluated in SMART-2 and SMART-5 using the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) sleep scale.Citation114,Citation115 Both doses of CE/BZA significantly reduced the time it takes to fall asleep and the amount of sleep disturbance in both studies.Citation114,Citation115 Both doses also improved sleep adequacy as well as scores on two sleep indices from the MOS sleep scale measuring overall sleep problems in SMART-2, whereas improvements on these outcomes were seen only with CE 0.625 mg/BZA 20 mg in SMART-5.Citation114,Citation115 Effect sizes for these improvements, reported in SMART-2, were medium to large.Citation114 In SMART-5, CE/MPA also improved time to fall asleep, sleep disturbance, sleep adequacy, and both sleep problem indices on the MOS sleep scale compared with placebo.Citation115

Using mediation modeling, Pinkerton et alCitation116 concluded that at week 12, a majority (78%–86%) of CE/BZA’s beneficial effects on sleep disturbance in the SMART-2 population of women with frequent moderate-to-severe hot flushes at baseline were attributable to direct effects rather than indirect effects resulting from reduction in the bothersomeness of hot flushes. However, the opposite was found in the SMART-5 population of women with less severe VMS: reduction of hot flushes accounted for 75%–92% of the effects on sleep disturbance.Citation116 In an analysis of a subgroup of more symptomatic women in SMART-5, results were more comparable to those of SMART-2; thus, CE/BZA appears to affect sleep more directly in women who have severe VMSs but more indirectly via improvements in VMS in women with less severe VMSs. Similarly, benefits of CE/MPA on sleep disturbance in the overall SMART-5 population were largely (96%–147%) attributable to reduction in VMSs.Citation116 This is consistent with results of another recent study, which found that transdermal estradiol did not improve sleep quality compared with placebo in postmenopausal women who had insomnia but not severe VMSs or hot flushes during sleep.Citation117

Treatment satisfaction was assessed via the Menopause Symptoms-Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire in SMART-2 and SMART-3.Citation86,Citation114 In both trials, CE 0.45 mg/BZA 20 mg and CE 0.625 mg/BZA 20 mg were associated with significantly (P<0.05) greater overall treatment satisfaction compared with placebo as well as greater satisfaction with control of daytime and nighttime hot flushes and effects on quality of sleep and mood/emotions.Citation86,Citation114 In the more symptomatic population in SMART-2, both doses of CE/BZA were also associated with greater satisfaction with treatment tolerability, and the approved dose was also associated with greater satisfaction with ability to concentrate.Citation114

Conclusion

CE/BZA is a good option for nonhysterectomized postmenopausal women who are seeking relief from bothersome menopausal symptoms; additionally, it avoids the use of a progestin. It is associated with significant benefits with regard to reduction of VMSs and prevention of bone loss, improves sleep and menopause-specific quality of life, and may improve vaginal lubrication and vaginal maturation index. Based on up to 2 years of follow-up, it provides acceptable protection of the endometrium and breast. Women using CE/BZA report a high rate of treatment satisfaction.

The choice between traditional HT and CE/BZA should be based on safety and tolerability as well as personal preferences. HT regimens containing progestins have been associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, increased breast density, breast pain/tenderness, and vaginal bleeding. Progestin-containing HT may also have a negative effect on mood in some progestin-sensitive women. During up to 2 years of CE/BZA use, incidence of those outcomes is comparable to that with placebo and lower than that with CE/MPA.

The success and safety of the available formulation of CE/BZA are based on the careful selection of the estrogen component (in this case, conjugated estrogens) and SERM used in this combination product, as well as the identification of a dose ratio that provides the best balance between therapeutic efficacy and endometrial safety.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support was provided by Lauren Cerruto at Peloton Advantage and was funded by Pfizer Inc. The Phase III SMART studies (NCT00808132, NCT00242710, NCT00234819, and NCT00675688) from which data on file have been reported here were sponsored by Wyeth Research, which was acquired by Pfizer Inc. in October 2009.

Disclosure

RK has served as a consultant/advisory board member for Amgen, Foundation for Osteoporosis Research and Education/American Bone Health, Merck & Co, Noven Pharmaceuticals, Novo Nordisk A/S, Own the Bone Advisory Board of the American Orthopedic Association, Pfizer, Shionogi, TherapeuticsMD, and Sprout; has received grants/research support (fees to Alta Bates Summit Medical Center, Jordan Research and Education Institute) from TherapeuticsMD; has served on a speaker’s bureau for Novo Nordisk A/S, Shionogi, Noven Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer; and has received editorial writing support from Pfizer and Shionogi. SRG has served as an advisory board member for Shionogi, Pfizer, JDS Therapeutics, Amgen, and Sermonix; served as a consultant for Cook OB/GYN and Philips Ultrasound; and has served on the speaker’s bureaus for Pfizer, Shionogi, and JDS Therapeutics. JHP has received consultant fees from Wyeth/Pfizer, Besins Healthcare, Shionogi, Metagenics, Radius Health, and TherapeuticsMD, and has stock options in TherapeuticsMD. BSK is an employee of Pfizer. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- PolitiMCSchleinitzMDColNFRevisiting the duration of vasomotor symptoms of menopause: a meta-analysisJ Gen Intern Med20082391507151318521690

- WilliamsREKalilaniLDiBenedettiDBFrequency and severity of vasomotor symptoms among peri- and postmenopausal women in the United StatesClimacteric2008111324318202963

- NappiREKokot-KierepaMVaginal health: insights, views & attitudes (VIVA) – results from an international surveyClimacteric2012151364422168244

- FreemanEWSammelMDSandersRJRisk of long-term hot flashes after natural menopause: evidence from the Penn Ovarian Aging Study cohortMenopause201421992493224473530

- GartoullaPWorsleyRBellRJDavisSRModerate to severe vasomotor and sexual symptoms remain problematic for women aged 60 to 65 yearsMenopause201522769470125706184

- HemminkiERegushevskayaELuotoRVeerusPVariability of bothersome menopausal symptoms over time – a longitudinal analysis using the Estonian postmenopausal hormone therapy trial (EPHT)BMC Womens Health2012124423259658

- GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death CollaboratorsGlobal, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013Lancet2015385996311717125530442

- AvisNECrawfordSLGreendaleGStudy of Women’s Health Across the NationDuration of menopausal vasomotor symptoms over the menopause transitionJAMA Intern Med2015175453153925686030

- The North American Menopause SocietyThe 2012 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause SocietyMenopause201219325727122367731

- StuenkelCAGassMLMansonJEA decade after the Women’s Health Initiative – the experts do agreeMenopause201219884684722776849

- ShifrenJLGassMLThe North American Menopause Society recommendations for clinical care of midlife womenMenopause201421101038106225225714

- de VilliersTJGassMLHainesCJGlobal consensus statement on menopausal hormone therapyClimacteric201316220320423488524

- de VilliersTJPinesAPanayNInternational Menopause SocietyUpdated 2013 International Menopause Society recommendations on menopausal hormone therapy and preventive strategies for midlife healthClimacteric201316331633723672656

- Neves-E-CastroMBirkhauserMSamsioeGEMAS position statement: the ten point guide to the integral management of menopausal healthMaturitas2015811889225757366

- KaunitzAMExtended duration use of menopausal hormone therapyMenopause201421667968124398408

- North American Menopause Society [webpage on the Internet]The North American Menopause Society statement on continuing use of systemic hormone therapy after age 65North American Menopause Society [updated 2015]. Available from: http://www.menopause.org/docs/default-source/2015/2015-nams-hormone-therapy-after-age-65.pdfAccessed June 9, 2015

- AndersonGLLimacherMAssafARWomen’s Health Initiative Steering CommitteeEffects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trialJAMA2004291141701171215082697

- RossouwJEAndersonGLPrenticeRLWriting Group for the Women’s Health Initiative InvestigatorsRisks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trialJAMA2002288332133312117397

- MansonJEChlebowskiRTStefanickMLMenopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trialsJAMA2013310131353136824084921

- HaysJOckeneJKBrunnerRLWomen’s Health Initiative InvestigatorsEffects of estrogen plus progestin on health-related quality of lifeN Engl J Med2003348191839185412642637

- ChlebowskiRTHendrixSLLangerRDWHI InvestigatorsInfluence of estrogen plus progestin on breast cancer and mammography in healthy postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trialJAMA2003289243243325312824205

- ChlebowskiRTAndersonGLGassMWHI InvestigatorsEstrogen plus progestin and breast cancer incidence and mortality in postmenopausal womenJAMA2010304151684169220959578

- AndersonGLChlebowskiRTAragakiAKConjugated equine oestrogen and breast cancer incidence and mortality in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: extended follow-up of the Women’s Health Initiative randomised placebo-controlled trialLancet Oncol201213547648622401913

- BarnabeiVMCochraneBBAragakiAKWomen’s Health Initiative InvestigatorsMenopausal symptoms and treatment-related effects of estrogen and progestin in the Women’s Health InitiativeObstet Gynecol20051055 pt 11063107315863546

- ReganMMEmondSKAttardoMJParkerRAGreenspanSLWhy do older women discontinue hormone replacement therapy?J Womens Health Gend Based Med200110434335011445025

- AmeyeLAntoineCPaesmansMde AzambujaERozenbergSMenopausal hormone therapy use in 17 European countries during the last decadeMaturitas201479328729125156453

- SpragueBLTrentham-DietzACroninKAA sustained decline in postmenopausal hormone use: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2010Obstet Gynecol2012120359560322914469

- Lohr A. [webpage on the Internet]First of its kind “menopause map” helps women navigate treatment [updated 2015] Available from: https://www.endocrine.org/news-room/press-release-archives/2012/first-of-its-kind-menopause-map-helps-women-navigate-treatmentAccessed July 2, 2015

- SarrelPPortmanDLefebvrePIncremental direct and indirect costs of untreated vasomotor symptomsMenopause201522326026625714236

- UtianWHPsychosocial and socioeconomic burden of vasomotor symptoms in menopause: a comprehensive reviewHealth Qual Life Outcomes200534716083502

- GartoullaPBellRJWorsleyRDavisSRModerate-severely bothersome vasomotor symptoms are associated with lowered psychological general wellbeing in women at midlifeMaturitas201581448749226115590

- SimonJANappiREKingsbergSAMaamariRBrownVClarifying vaginal atrophy’s impact on sex and relationships (CLOSER) survey: emotional and physical impact of vaginal discomfort on North American postmenopausal women and their partnersMenopause201421213714223736862

- SimonJAKokot-KierepaMGoldsteinJNappiREVaginal health in the United States: results from the vaginal health: insights, views & attitudes surveyMenopause201320101043104823571518

- PinkertonJVSantoroNCompounded bioidentical hormone therapy: identifying use trends and knowledge gaps among US womenMenopause201522992693625692877

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. [webpage on the Internet]Committee opinion 532: compounded bioidentical menopausal hormone therapy [updated August, 2012]. Available from: http://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Gynecologic-Practice/Compounded-Bioidentical-Menopausal-Hormone-TherapyAccessed August 21, 2014

- RossouwJEPrenticeRLMansonJEPostmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of cardiovascular disease by age and years since menopauseJAMA2007297131465147717405972

- The North American Menopause SocietyManagement of symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy: 2013 position statement of The North American Menopause SocietyMenopause201320988890223985562

- GoodmanMPAre all estrogens created equal? A review of oral vs. transdermal therapyJ Womens Health (Larchmt)201221216116922011208

- FilesJAMillerVMChaSSPruthiSEffects of different hormone therapies on breast pain in recently postmenopausal women: findings from the Mayo Clinic KEEPS breast pain ancillary studyJ Womens Health (Larchmt)2014231080180525268853

- KlingJMLahrBABaileyKRHarmanSMMillerVMMulvaghSLEndothelial function in women of the Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention StudyClimacteric201518218719725417709

- MillerVMLahrBDBaileyKRHeitJAHarmanSMJayachandranMLongitudinal effects of menopausal hormone treatments on platelet characteristics and cell-derived microvesiclesPlatelets2015 Epub201549

- Osphena [package insert]Florham Park, NJShionogi Inc.2015

- BachmannGAKomiJOOspemifene effectively treats vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: results from a pivotal phase 3 studyMenopause201017348048620032798

- PortmanDJBachmannGASimonJAOspemifene, a novel selective estrogen receptor modulator for treating dyspareunia associated with postmenopausal vulvar and vaginal atrophyMenopause201320662363023361170

- PortmanDJGassMLGenitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause SocietyMenopause201421101063106825160739

- SimonJALinVHRadovichCBachmannGAOne-year long-term safety extension study of ospemifene for the treatment of vulvar and vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women with a uterusMenopause201320441842723096251

- McClungMRSirisECummingsSPrevention of bone loss in postmenopausal women treated with lasofoxifene compared with raloxifeneMenopause200613337738616735934

- FisherBCostantinoJPWickerhamDLTamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer: report of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 StudyJ Natl Cancer Inst19989018137113889747868

- ChristiansenCChesnutCH3rdAdachiJDSafety of bazedoxifene in a randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled Phase 3 study of postmenopausal women with osteoporosisBMC Musculoskelet Disord20101113020569451

- Brisdelle [package insert]Miami, FLNoven Therapeutics, LLC2013

- SimonJAPortmanDJKaunitzAMLow-dose paroxetine 7.5 mg for menopausal vasomotor symptoms: two randomized controlled trialsMenopause201320101027103524045678

- PortmanDJKaunitzAMKazempourKMekonnenHBhaskarSLippmanJEffects of low-dose paroxetine 7.5 mg on weight and sexual function during treatment of vasomotor symptoms associated with menopauseMenopause201421101082109024552977

- PinkertonJVArcherDFGuico-PabiaCJHwangEChengRFMaintenance of the efficacy of desvenlafaxine in menopausal vasomotor symptoms: a 1-year randomized controlled trialMenopause2013201384623266839

- ClinicalTrials.gov [webpage on the Internet]Estradiol vaginal softgel capsules in treating symptoms of vulvar and vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women (REJOICE) NCT02253173ClinicalTrials.gov [updated April 28, 2015]. Available from: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02253173Accessed June 9, 2015

- MirkinSAmadioJMBernickBAPickarJHArcherDF17beta-Estradiol and natural progesterone for menopausal hormone therapy: REPLENISH phase 3 study design of a combination capsule and evidence reviewMaturitas2015811283525835751

- PickarJHBonCAmadioJMMirkinSBernickBPharmacokinetics of the first combination 17beta-estradiol/progesterone capsule in clinical development for menopausal hormone therapyMenopause201522121308131625944519

- ClinicalTrials.gov [webpage on the Internet]A safety and efficacy study of the combination estradiol and progesterone to treat vasomotor symptoms (REPLENISH) NCT01942668ClinicalTrials.gov [updated May 5, 2015]. Available from: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01942668?term=REPLENISH&rank=1Accessed June 9, 2015

- FreemanEWGuthrieKACaanBEfficacy of escitalopram for hot flashes in healthy menopausal women: a randomized controlled trialJAMA2011305326727421245182

- GordonPRKerwinJPBoesenKGSenfJSertraline to treat hot flashes: a randomized controlled, double-blind, crossover trial in a general populationMenopause200613456857516837878

- JoffeHGuthrieKALaCroixAZLow-dose estradiol and the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor venlafaxine for vasomotor symptoms: a randomized clinical trialJAMA Intern Med201417471058106624861828

- PinkertonJVKaganRPortmanDSathyanarayanaRSweeneyMPhase 3 randomized controlled study of gastroretentive gabapentin for the treatment of moderate-to-severe hot flashes in menopauseMenopause201421656757324149930

- KharodeYBodinePVMillerCPLyttleCRKommBSThe pairing of a selective estrogen receptor modulator, bazedoxifene, with conjugated estrogens as a new paradigm for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and osteoporosis preventionEndocrinology2008149126084609118703623

- KommBSMirkinSJenkinsSNDevelopment of conjugated estrogens/bazedoxifene, the first tissue selective estrogen complex (TSEC) for management of menopausal hot flashes and postmenopausal bone lossSteroids201490718124929044

- SweetlandSBeralVBalkwillAMillion Women Study CollaboratorsVenous thromboembolism risk in relation to use of different types of postmenopausal hormone therapy in a large prospective studyJ Thromb Haemost2012102277228622963114

- SmithNLBlondonMWigginsKLLower risk of cardiovascular events in postmenopausal women taking oral estradiol compared with oral conjugated equine estrogensJAMA Intern Med20141741253124081194

- ShufeltCLMerzCNPrenticeRLHormone therapy dose, formulation, route of delivery, and risk of cardiovascular events in women: findings from the Women’s Health Initiative Observational StudyMenopause201421326026624045672

- EthunKFWoodCEClineJMRegisterTCApptSEClarksonTBEndometrial profile of bazedoxifene acetate alone and in combination with conjugated equine estrogens in a primate modelMenopause201320777778423793168

- EthunKFWoodCERegisterTCClineJMApptSEClarksonTBEffects of bazedoxifene acetate with and without conjugated equine estrogens on the breast of postmenopausal monkeysMenopause201219111242125223103754

- KulakJJrFischerCKommBTaylorHSTreatment with bazedoxifene, a selective estrogen receptor modulator, causes regression of endometriosis in a mouse modelEndocrinology201115283226323221586552

- Lewis-WambiJSKimHCurpanRGriggRSarkerMAJordanVCThe selective estrogen receptor modulator bazedoxifene inhibits hormone-independent breast cancer cell growth and down-regulates estrogen receptor alpha and cyclin D1Mol Pharmacol201180461062021737572

- WardellSENelsonERChaoCAMcDonnellDPBazedoxifene exhibits antiestrogenic activity in animal models of tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer: implications for treatment of advanced diseaseClin Cancer Res20131992420243123536434

- PeanoBJCrabtreeJSKommBSWinnekerRCHarrisHAEffects of various selective estrogen receptor modulators with or without conjugated estrogens on mouse mammary glandEndocrinology200915041897190319022889

- ChangKCWangYBodinePVNagpalSKommBSGene expression profiling studies of three SERMs and their conjugated estrogen combinations in human breast cancer cells: insights into the unique antagonistic effects of bazedoxifene on conjugated estrogensJ Steroid Biochem Mol Biol20101181–211712419914376

- SongYSantenRJWangJPYueWInhibitory effects of a bazedoxifene/conjugated equine estrogen combination on human breast cancer cells in vitroEndocrinology2013154265666523254198

- StovallDWUtianWHGassMLThe effects of combined raloxifene and oral estrogen on vasomotor symptoms and endometrial safetyMenopause2007143 pt 151051717314736

- Van DurenDRonkinSPickarJConstantineGBazedoxifene combined with conjugated estrogens: a novel alternative to traditional hormone therapies [abstract O-206]Fertil Steril2006863 supplS88S89

- PickarJHYehITBachmannGSperoffLEndometrial effects of a tissue selective estrogen complex containing bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens as a menopausal therapyFertil Steril20099231018102419635613

- LoboRAPinkertonJVGassMLEvaluation of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and effects on metabolic parameters and overall safety profileFertil Steril20099231025103819635615

- PinkertonJVUtianWHConstantineGDOlivierSPickarJHRelief of vasomotor symptoms with the tissue-selective estrogen complex containing bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens: a randomized, controlled trialMenopause20091661116112419546826

- FreemanEWEnsrudKELarsonJCPlacebo improvement in pharmacologic treatment of menopausal hot flashes: time course, duration, and predictorsPsychosom Med201577216717525647753

- PinkertonJVAbrahamLBushmakinAGEvaluation of the efficacy and safety of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for secondary outcomes including vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women by years since menopause in the Selective estrogens, Menopause, And Response to Therapy (SMART) trialsJ Womens Health (Larchmt)2014231182824206058

- LindsayRGallagherJCKaganRPickarJHConstantineGEfficacy of tissue-selective estrogen complex of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for osteoporosis prevention in at-risk postmenopausal womenFertil Steril20099231045105219635616

- MirkinSKommBSPanKChinesAAEffects of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens on endometrial safety and bone in postmenopausal womenClimacteric201316333834623038989

- PinkertonJVHarveyJALindsayRSMART-5 InvestigatorsEffects of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens on the endometrium and bone: a randomized trialJ Clin Endocrinol Metab2014992E189E19824438370

- KaganRWilliamsRSPanKMirkinSPickarJHA randomized, placebo- and active-controlled trial of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for treatment of moderate to severe vulvar/vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal womenMenopause201017228128919779382

- BachmannGBobulaJMirkinSEffects of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens on quality of life in postmenopausal women with symptoms of vulvar/vaginal atrophyClimacteric201013213214019863455

- Guidance for Industry [webpage on the Internet]Estrogen and estrogen/progestin drug products to treat vasomotor symptoms and vulvar and vaginal atrophy symptoms – recommendaitons for clinical evaluationFood and Drug Administration [updated January, 2003]. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatory-information/guidances/ucm071643.pdfAccessed January 6, 2014

- European Medicines Agency [webpage on the Internet]Guideline on clinical investigation of medicinal products for hormone replacement therapy of oestrogen deficiency symptoms in postmenopausal womenEuropean Medicines Agency [updated May 1, 2006]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500003348.pdfAccessed May 19, 2014

- KulakJJrFerrianiRAKommBSTaylorHSTissue selective estrogen complexes (TSECs) differentially modulate markers of proliferation and differentiation in endometrial cellsReprod Sci201320212913723171676

- ClarkeCLSutherlandRLProgestin regulation of cellular proliferationEndocr Rev19901122663012114281

- MirkinSPinkertonJVKaganRGynecologic safety of conjugated estrogens plus bazedoxifene: pooled analysis of 5 phase 3 trialsJ Womens Health Accepted for publication

- PalaciosSSilvermanSLde VilliersTJBazedoxifene Study GroupA 7-year randomized, placebo-controlled trial assessing the long-term efficacy and safety of bazedoxifene in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: effects on bone density and fractureMenopause201522880681325668306

- HarveyJAPinkertonJVBaracatECShiHChinesAAMirkinSBreast density changes in a randomized controlled trial evaluating bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogensMenopause201320213814523271189

- PinkertonJVHarveyJAPanKBreast effects of bazedoxifene-conjugated estrogens: a randomized controlled trialObstet Gynecol2013121595996823635731

- CrandallCJAragakiAKCauleyJABreast tenderness after initiation of conjugated equine estrogens and mammographic density changeBreast Cancer Res Treat2012131396997921979747

- AssiVMassatNJThomasSA case-control study to assess the impact of mammographic density on breast cancer risk in women aged 40–49 at intermediate familial riskInt J Cancer2015136102378238725333209

- BoydNFLockwoodGAByngJWTritchlerDLYaffeMJMammographic densities and breast cancer riskCancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev1998712113311449865433

- CarneyPAMigliorettiDLYankaskasBCIndividual and combined effects of age, breast density, and hormone replacement therapy use on the accuracy of screening mammographyAnn Intern Med2003138316817512558355

- PalaciosSde VilliersTJNardoneFCBZA Study GroupAssessment of the safety of long-term bazedoxifene treatment on the reproductive tract in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: results of a 7-year, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 studyMaturitas2013761818723871271

- KommBSThompsonJRMirkinSCardiovascular safety of conjugated estrogens plus bazedoxifene: meta-analysis of the SMART trialsClimacteric201518119

- CurbJDPrenticeRLBrayPFVenous thrombosis and conjugated equine estrogen in women without a uterusArch Intern Med2006166777278016606815

- MirkinSPanKRyanKAChinesAStevensonJCA pooled analysis of the effects of conjugated estrogens/bazedoxifene on lipid parameters in postmenopausal women from the Selective estrogens, Menopause, And Response to Therapy (SMART) trialsJ Clin Endocrinol Metab201510062329233825894963

- ArcherDFLewisVCarrBROlivierSPickarJHBazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens (BZA/CE): incidence of uterine bleeding in postmenopausal womenFertil Steril20099231039104419635614

- GoldsteinSRKaganRIncidence of bleeding or spotting with a conjugated estrogen/bazedoxifene compound compared to conjugated estrogen/progestogen to placeboPoster P-31 Presented at: Annual Meeting of the North American Menopause SocietySeptember 30–October 3, 2015Las Vegas, NV.

- CrandallCJAragakiAKCauleyJABreast tenderness and breast cancer risk in the estrogen plus progestin and estrogen-alone Women’s Health Initiative clinical trialsBreast Cancer Res Treat2012132127528522042371

- GirdlerSSO’BriantCSteegeJGrewenKLightKCA comparison of the effect of estrogen with or without progesterone on mood and physical symptoms in postmenopausal womenJ Womens Health Gend Based Med19998563764610839650

- JungSJShinAKangDHormone-related factors and post-menopausal onset depression: results from KNHANES (2010–2012)J Affect Disord201517517618325622021

- GleasonCEDowlingNMWhartonWEffects of hormone therapy on cognition and mood in recently postmenopausal women: findings from the randomized, controlled KEEPS-cognitive and affective studyPLoS Med2015126e100183326035291

- SitesCKL’HommedieuGDTothMJBrochuMCooperBCFairhurstPAThe effect of hormone replacement therapy on body composition, body fat distribution, and insulin sensitivity in menopausal women: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialJ Clin Endocrinol Metab20059052701270715687338

- GodslandIFGangarKWaltonCInsulin resistance, secretion, and elimination in postmenopausal women receiving oral or transdermal hormone replacement therapyMetabolism19934278468538345794

- ShadoanMKKavanaghKZhangLAnthonyMSWagnerJDAddition of medroxyprogesterone acetate to conjugated equine estrogens results in insulin resistance in adipose tissueMetabolism200756683083717512317

- SpencerCPGodslandIFCooperAJRossDWhiteheadMIStevensonJCEffects of oral and transdermal 17beta-estradiol with cyclical oral norethindrone acetate on insulin sensitivity, secretion, and elimination in postmenopausal womenMetabolism200049674274710877199

- AbrahamLPinkertonJVMessigMRyanKAKommBSMirkinSMenopause-specific quality of life across varying menopausal populations with conjugated estrogens/bazedoxifeneMaturitas201478321221824837362

- UtianWYuHBobulaJMirkinSOlivierSPickarJHBazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens and quality of life in postmenopausal womenMaturitas200963432933519647382

- PinkertonJVPanKAbrahamLSleep parameters and health-related quality of life with bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens: a randomized trialMenopause201421325225923942245

- PinkertonJVBushmakinAGRacketaJCappelleriJCChinesAAMirkinSEvaluation of the direct and indirect effects of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens on sleep disturbance using mediation modelingMenopause201421324325123899830

- TansupswatdikulPChaikittisilpaSJaimchariyatamNPanyakhamlerdKJaisamrarnUTaechakraichanaNEffects of estrogen therapy on postmenopausal sleep quality regardless of vasomotor symptoms: a randomized trialClimacteric201518219820425242569