Abstract

Allergic diseases comprise a genetically heterogeneous group of chronic, immunomediated diseases. It has been clearly reported that the prevalence of these diseases has been on the rise for the last few decades, but at different rates, in various areas of the world. This paper discusses the epidemiology of allergic diseases among children and their negative impact on affected patients, their families, and societies. These effects include the adverse effects on quality of life and economic costs. Medical interest has shifted from tertiary or secondary prevention to primary prevention of these chronic diseases among high-risk infants in early life. Being simple, practical, and cost-effective are mandatory features for any candidate methods delivering these strategies. Dietary therapy fits this model well, as it is simple, practical, and cost-effective, and involves diverse methods. The highest priority strategy is feeding these infants breast milk. For those who are not breast-fed, there should be a strategy to maintain beneficial gut flora that positively influences intestinal immunity. We review the current use of probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics, and safety and adverse effects. Other dietary modalities of possible potential in achieving this primary prevention, such as a Mediterranean diet, use of milk formula with modified (hydrolyzed) proteins, and the role of micronutrients, are also explored. Breast-feeding is effective in reducing the risk of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic eczema among children. In addition, breast milk constitutes a major source of support for gut microbe colonization, due to its bifidobacteria and galactooligosaccharide content. The literature lacks consensus in recommending the addition of probiotics to foods for prevention and treatment of allergic diseases, while prebiotics may prove to be effective in reducing atopy in healthy children. There is insufficient evidence to support soy formulas or amino acid formulas for prevention of allergic disease. A healthy diet, such as the Mediterranean diet, may have a protective effect on the development of asthma and atopy in children. In children with asthma and allergic diseases, vitamin D deficiency correlates strongly with asthma, allergic rhinitis, and wheezing.

Background

Allergic diseases comprise a genetically heterogeneous group of chronic, immunomediated diseasesCitation1,Citation2 that mainly involve bronchial asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, food allergy, and acute urticaria. They are more prevalent among children than adults. Worldwide, respiratory allergic diseases alone, namely asthma and allergic rhinitis, affect nearly 700 million subjects.Citation3 It has been clearly reported that the prevalence of these diseases has been on the rise for the last few decades, but at different rates, in various areas of the world.Citation3,Citation4 Currently, bronchial asthma is considered the most common chronic, noninfectious condition among children.Citation4 In some industrialized countries, the prevalence of asthma is close to 35%–40%, whereas it is less than 5% in other communities;Citation5 furthermore, relatively new reports have shown that the prevalence of asthma is increasing in many low- and middle-income nations.Citation4,Citation6

The impact of allergic diseases is tremendous on affected individuals, their families, and societies. They adversely affect quality of life and increase the rate of comorbid conditions and risk of death, as noticed in asthma.Citation3,Citation7 In addition, the economic burden of these diseases is considerable. This is usually related to the substantial direct medical cost (emergency department visits, physician’s office visits, hospitalizations, diagnostic laboratory and radiological workup, and other modalities of therapy) and indirect medical costs (numerous absences from labor or school, reduced productivity, and diminished school performance).Citation3,Citation7–Citation9

Allergic diseases are intricate diseases resulting from the interaction of genetic and environmental factors.Citation10 The latter include infectious agents (human rhinoviruses, respiratory syncytial virus, and mycoplasma), allergens (house dust mites, pollens, pets, and molds), pollutants, and medication exposure.Citation11–Citation13

During the last 2 decades, primary prevention of allergic diseases and asthma (prevention of immunological sanitization, development of IgE antibodies) has proved to be a more effective strategy than secondary prevention (preventing the development of an allergic disease following sensitization) or tertiary prevention (treatment of asthma of allergic diseases).Citation14 As a strategy, primary prevention of allergic diseases includes 1) allergen avoidance, 2) restoration of gut microbiota–intestinal immunity relationship, 3) dietary pattern, 4) intake of modified dietary proteins in early life, and 5) micronutrients.

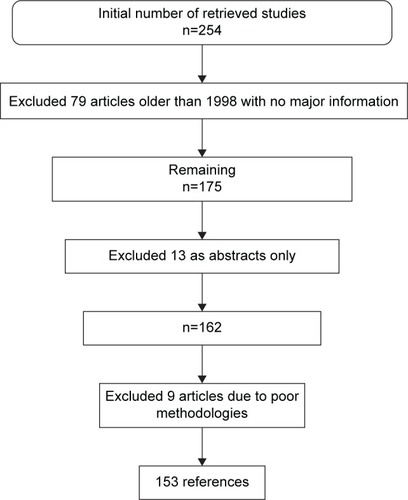

The Cochrane Library, Embase, Medline, and Google Scholar databases were searched in March 2015 (from inception to March 2015) for randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quasi-RCTs, and review articles that were published in English and Spanish. In addition, we searched the references of the identified articles for additional articles. We used a wide variety of different combinations of the following terms: allergy, primary, prevention, children, mothers, diet, milk, formula, breast-feeding, prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics, Mediterranean, micronutrients, and fatty acids. We identified and reviewed 254 manuscripts, but filtered to 153 references (). This review paper focuses on primary prevention of allergic diseases in children.

Restoration of gut microbiota–intestinal immunity relationship

Since the allergy-high-risk infant (born to one or more allergic parent, and/or allergic sibling) is healthy, the strategy of preventing immunity alteration is aimed at the preservation of the “beneficial” gut microbiota in the newborn, and thus preventing deviations of the local intestinal immunity and consequently the systemic immunity to the proallergic side. To understand the rationale behind this preventive strategy, the bacterial colonization of gut, infant intestinal microbiota–intestinal immune interaction, and imbalances in the composition of the intestinal microbiota leading to allergic diseases have to be explored.

Gut microbiota, intestinal immunity, and allergic diseases

Microbial gut colonization typically commences at the time of birth, and is influenced by the load (inoculum) of the first maternal microbiota, type of delivery (cesarean section vs vaginal delivery), feeding practices (formula-feeding vs breast-feeding), and antimicrobial use.Citation15–Citation17 The maternal intestinal microbiota clearly determines the type of infant’s intestinal microbiota in the first few months of life.Citation18 Moreover, it takes a few months for the bacterial species to become steadily consistent, despite the early life complete colonization.Citation16,Citation19 At the age of 1 month, infants born via cesarean section demonstrate similar numbers of gut bacteria to those who were vaginally delivered, but with higher rates of Clostridium spp., Klebsiella spp., Enterobacteriaceae, Bacteroides spp., Bifidobacterium spp., and Escherichia coli.Citation16,Citation20,Citation21 This effect extends beyond the age of 6 months in infants born via cesarean section,Citation22 increasing the risk of atopy, asthma, and allergic rhinitis.Citation23 In normal breast-fed infants, Bifidobacterium spp. predominate the gut microbiota (60%–70%), compared to formula-fed infants, where Bacteroides and Clostridium spp. and Enterobacteriaceae prevail.Citation16,Citation21 Perturbations in the intestinal microbial profile result in the reduction of the predominance of Bifidobacterium spp. or rise of unbeneficial microbiota, leading to increased risk of allergies, infections,Citation19 and other diseases.Citation24

In the newborn period, the gut microbiota plays a crucial role in promoting and maintaining the mucosal immune system, both in terms of its physical factors and function, and in maintaining a very well-balanced immune response. Gut-associated mucosal lymphoid tissue becomes reactive to pathogenic bacteria but tolerant to “beneficial” bacteria. Moreover, the intestinal microbiota plays an important role in the development of tolerogenic dendritic cells from the mesenteric lymph nodes of the gut-associated mucosal lymphoid tissue and in the production of secretory IgA.Citation25,Citation26

The intestinal epithelia express various pathogen-recognition receptors, including Toll-like receptors and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptors that activate immune response against pathogens. Since pathogenic bacteria and gut commensals express many of these pathogen-associated molecular patterns, there is tight control on the immune-response mechanisms so that it will recognize and specifically respond to pathogens, but at the same time remain tolerant to commensals. These mechanisms involve intestinal epithelial cells, Toll-like receptors, dendritic cells, and T-regulatory (Treg) cells.Citation27

It is known that T-helper (Th)-2 cells are characterized by their production of IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, and IL-13, which contribute to the development of and maintenance of allergic inflammatory process, while Th1 cells produce TNFα and IFNγ, which contribute in the modulation of cell-mediated immunity.Citation27,Citation28

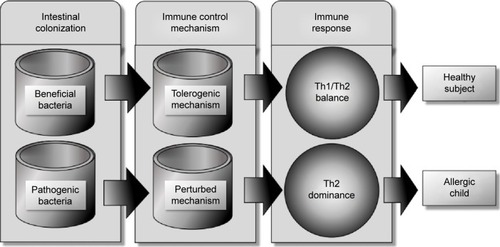

Treg cells, however, maintain immunological tolerance due to their immunomodulatory or immunosuppressive capabilities, and are key players in regulating immune response in nondisease states.Citation27 Changes in Treg numbers or functions are usually associated with development of allergic disease (). Basic animal studies on germ-free mice revealed that in the absence of microbial colonization, T-cells produced more Th2 cytokines. This Th2-cell predominance was corrected with colonization of germ-free mice with Bacteroides fragilis alone, which promoted Th1 response and restored the Th1/Th2 imbalance.Citation28 Evidence from clinical studies also demonstrated that probiotic bacteria reduced Th2 cytokine patterns while promoting Th1 response.Citation29 The intestinal microbiota have marked immunomodulatory effects that are essential in maintaining immune tolerance. It has been proposed that certain diseases, such as eczema, asthma, allergic rhinitis, type 1 diabetes mellitus, and inflammatory bowel diseases, are linked to the dysregulation of the development of the intestinal mucosal defense system.Citation30

Figure 2 In early infancy, colonization with beneficial flora stimulates the intestinal immunity to develop immunotolerance through intraintestinal epithelial cells and dendritic cells and their surface markers, leading to balanced Th1/Th2 immune response.

Abbreviation: Th, T-helper.

The composition of intestinal microflora differs between atopic and healthy infants.Citation20 Atopic children have lower counts of Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, and Bacteroides spp.Citation31 A recent systematic review by Melli et alCitation32 on the role of intestinal microbiota and allergic diseases among children revealed that in allergic children, early life microbiota was of lower diversity, predominantly Firmicutes; the same group of children also showed a higher amount of Bacteroidaceae and anaerobic bacteria, particularly B. fragilis, E. coli, Clostridium difficile, Bifidobacterium catenulatum, and B. bifidum, and fewer B. adolescentis, B. bifidum, and Lactobacillus. Well-conducted clinical trials have provided good data on the preventive benefit of probiotics (Lactobacillus or Bifidobacterium) in pregnant women and their infants in reducing the risk of allergic diseases, especially atopic dermatitis.Citation33,Citation34

Breast milk constitutes a major source of support to gut colonization, due to its Bifidobacterium content and its composition of a large amount of galactooligosaccharides (GOS), which selectively accelerate the growth of bifidobacteria.Citation35,Citation36 Multiple, recent, and large epidemiological studies confirmed the beneficial effects of breast-feeding in reducing the risk of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic eczema among children.Citation37–Citation39

Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics

Probiotics are defined as supplements that contain microorganisms (bacteria, yeast) and can change the microflora of the host.Citation40,Citation41 The European Food and Feed Cultures Association and the International Life Sciences Institute defined probiotic as “a live microbial food ingredient that, when consumed in adequate amounts, confers health benefits on the consumers” and “live microorganisms that, when ingested or locally applied in sufficient numbers, provide the consumer with one or more proven health benefits”.Citation42,Citation43 Probiotics might be effective in preventing antibiotic-related diarrhea in healthy children and necrotizing enterocolitis in very low-birth-weight infants, as well as preventing childhood atopy and treating acute viral gastroenteritis; moreover, probiotics might be beneficial in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome, chronic ulcerative colitis, infantile colic, and Helicobacter pylori gastritis.Citation41 The strains of probiotics most commonly used are Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus spp.,Citation44,Citation45 which are also well known to have the capacity of resisting the physicochemical environment of the digestive tract.Citation46

On the other hand, prebiotics are aliments or supplements that contain a variety of molecules that stimulate the activity and/or growth of the native probiotic bacteria; a common component of prebiotics is fiber/oligosaccharides.Citation41 In the absence of fiber in the colon, anaerobic bacteria obtain their energy from protein fermentation, producing toxic metabolites, such as phenolic and ammoniac compounds.Citation47,Citation48 By contrast, microbiota metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids produce nontoxic material, such as propionate, butyrate, or acetate.Citation47,Citation49 In a study conducted on rats, Gourgue-Jeannot et alCitation50 found that providing a fructan (inulin, fructooligosaccharide [FOS]) diet increased the synthesis of short-chain fatty acids. Currently, the most commonly used prebiotics are soybean oligosaccharides, FOS, GOS, and inulin.Citation51,Citation52 Synbiotics are simply a mix of probiotic and prebiotic, which synergistically promote the growth of beneficial bacteria.Citation53,Citation54

Use of probiotics in prevention of allergic diseases

Asthma

Several studies have been conducted using murine models to assess the effectiveness of probiotics in the treatment and prevention of asthma and hypersensitive airways. Blümer et alCitation55 studied the perinatal maternal administration of probiotics in mice. The study showed that application of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) suppressed significantly allergic airways and peribronchial inflammation in mouse offspring. In another murine model, Feleszko et alCitation56 found that application of either LGG or Bifidobacterium lactis (Bb12) significantly decreased pulmonary eosinophilia, airway reactivity, and antigen-specific IgE production. Moreover, the administration of a recombinant or wild-type Lactobacillus plantarum can effectively reduce airway eosinophilia following aerosolized allergen exposure.Citation57 Furthermore coadministration of L. plantarum and Lactococcus lactis has been shown to reduce allergen-induced basophil degranulation in a murine model of birch-pollen allergy.Citation58 Two different studies showed that oral administration of live Lactobacillus reuteri reduced hyperresponsiveness to methacholine, airway eosinophilia, and local cytokine responses.Citation59,Citation60 There have also been several studies conducted on human beings, including children. Stockert et alCitation61 found that using laser acupuncture and probiotics in school-age children with asthma might prevent acute respiratory exacerbations and decrease bronchial hyperreactivity. However, two studies showed no efficacy of oral L. rhamnosus administration to adolescents suffering from pollen allergy.Citation62,Citation63 Moreover, a systematic review of RCTs showed that the effectiveness of probiotics for the treatment of allergic rhinitis and asthma is questionable.Citation64

Atopic dermatitis

Management with LGG may ameliorate eczema/dermatitis syndrome symptoms in IgE-sensitized infants, but not in non-IgE-sensitized infants.Citation65 In IgE-sensitized children, treatment with L. rhamnosus results in tangible reduction in the prevalence of any IgE-associated eczema.Citation65,Citation66 Rosenfeldt et alCitation67 reported that the use of two Lactobacillus strains (rhamnosus and reuteri) in the treatment of allergic dermatitis was effective in children with increased IgE levels. In a review that included 13 RCTs, Betsi et alCitation68 concluded that regardless of IgE-sensitization, probiotics, especially LGG, can prevent atopic dermatitis. Vliagoftis et alCitation64 had the same conclusion in a meta-analysis of eleven studies. Furthermore, a meta-analysis showed that administration of probiotics during pregnancy reduced the risk of atopic eczema in children aged 2–7 years whose mothers received probiotics during pregnancy (reduction 5.7%, P=0.022).Citation69

Regardless of the timing of administration (pregnancy or early life), probiotics seem to prevent atopic dermatitis and IgE-associated atopic dermatitis in infants.Citation70 Han et alCitation71 mentioned that probiotic L. plantarum CJLP133 supplementation is of good value in the treatment of pediatric atopic dermatitis. The preventive effect of LGG on atopic eczema has been also described in infants during the first 6 months of life.Citation72 However, Kopp and SalfeldCitation73 presented a different opinion. In addition, Taylor et alCitation74 challenged the use of early probiotic supplementation with L. acidophilus, and found that it did not reduce the risk of atopic dermatitis in high-risk infants, but on the contrary was linked with increased allergen sensitization in infants receiving complements. In addition, Gore et alCitation75 found there was no usefulness from supplementation with B. lactis or Lactobacillus paracasei in the treatment of eczema, or benefits on the progression of allergic disease from age 1–3 years. Moreover, other authors found little evidence to support the idea of routine supplementation of probiotics to either infants or pregnant women to prevent allergic diseases in childhood.Citation76,Citation77

Nonetheless, two major meta-analyses and one Cochrane study inferred that probiotics were not effective for the treatment for eczema.Citation78–Citation80 Furthermore, RCT studies showed that the probiotic effect was not steady over the long term (4–7 years),Citation72,Citation81 or even in the short term (6 months).Citation82 Dotterud et alCitation83 conducted an RCT to assess the effect of perinatal administration of probiotics on childhood asthma or atopic sensitization. A total of 415 pregnant women were randomized to receive probiotics (LGG, L. acidophilus La-5 and B. animalis subsp. lactis Bb12) or placebo. At 2 years, there were no substantial effects on asthma or atopic sensitization in the group that received probiotics compared to placebo. The heterogeneity in results in different studies is perhaps attributable to different probiotic strains used, environmental factors, such as diet or geographic region, and genetic liability.Citation76,Citation84

Allergic rhinitis

Probiotic treatment is beneficial in decreasing symptoms and reducing the use of relief medications in patients with seasonal and perennial allergic rhinitis.Citation64,Citation73,Citation85,Citation86 Moreover, probiotic VSL3® (Sigma-Tau Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Gaithersburg, MD, USA) can prevent the development of Parietaria major allergen-specific local and systemic response when administered intranasally to mice.Citation87

In a double-blind RCT, Giovannini et alCitation88 reported that long-term (12 months) consumption of fermented milk containing L. casei may improve the health status of preschool children with allergic rhinitis. Kuitunen et alCitation89 showed that probiotics can prevent IgE-associated allergy until the age of 5 years in cesarean-delivered children. Moreover, L. rhamnosus HN001 can protect against eczema and rhinoconjunctivitis when given in the first 2 years of life.Citation90 Furthermore, studies have shown that fermented milk prepared with Lactobacillus gasseri-, LGG-, and B. longum-supplemented yogurt can ameliorate nasal blockage and hence be effective in seasonal allergic rhinitis, such as in Japanese cedar pollinosis.Citation91–Citation94

However, a meta-analysis reported no benefits of probiotic use for allergic rhinitis.Citation77 In addition, Tamura et alCitation95 concluded in their study that fermented milk containing L. casei strain Shirota was futile in preventing allergic symptoms, including Japanese cedar pollinosis.

Food allergy

It has been reported that oral intake of Lactobacillus or Bifidobacterium strains could improve food allergy.Citation96 In a murine-based study, oral administration of L. acidophilus AD031 and B. lactis AD011 prevented ovalbumin-induced food allergy in mice.Citation97 Other studies showed that administration of L. casei strain Shirota or VSL3 reduced anaphylaxis in a food-allergy model in mice.Citation87,Citation97,Citation98 Isolauri et alCitation99 mentioned in their study that supplementation of formulas with LGG ameliorated gastrointestinal symptoms in infants with eczema.

In contrast, administration of B. lactis Bb-12 and L. casei to extensively hydrolyzed formula did not improve cow’s milk tolerance in infants with cow’s milk allergy.Citation100 Moreover, other studies concluded that probiotics, specifically LGG or L. acidophilus, do not protect against cow’s milk allergy in infancy.Citation74,Citation78,Citation96,Citation101 Finally, Osborn and SinnCitation77 stated in their review involving 1,549 infants that the benefit of probiotics in improving food hypersensitivity is questionable.

Probiotic safety in disease prevention

Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium as probiotics are considered to have a safe profile; however, there are limited data regarding the safety of other bacteria.Citation102 The rate of systemic infection with probiotic strains has been reported as 0.05%–0.4% in a large study conducted on adults,Citation103 but it is very rare in infants and children.Citation104–Citation106 Allen et alCitation107 reported that lactobacilli and bifidobacteria are well tolerated with no adverse effects during pregnancy and in infants. Probiotic products may include hidden allergens of food, and might not be suitable for patients with allergies to cow’s milk or hen’s eggs.Citation108 Other side effects of probiotics on children have been restricted to case reports. For instance, Robin et alCitation109 reported L. rhamnosus meningitis following recurrent episodes of bacteremia in a child undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation Moreover, Vahabnezhad et alCitation110 reported Lactobacillus bacteremia associated with probiotic use in a pediatric patient with ulcerative colitis receiving systemic corticosteroids and infliximab, while Luong et alCitation111 reported a case of Lactobacillus empyema in an HIV-infected immunodeficient patient with a lung transplant receiving a probiotic containing LGG. Bacteremia due to Lactobacillus supplementation was also reported in an immunocompetent infant and child without gastrointestinal diseases.Citation112 Finally, antibiotic resistance could emerge due to the long-term use of probiotics under antibiotic-selection pressure, and the resistance gene could be conveyed to other bacteria.Citation113

Use of prebiotics in prevention and treatment of allergic diseases

It has been postulated that prebiotics in infant formulas have the potential to prevent sensitization of infants to dietary allergens. In a 2-year follow-up RCT involving 132 infants at risk of atopy because of strong parental history, Arslanoglu et alCitation114 reported that the cumulative incidences for atopic dermatitis, recurrent wheezing, and allergic urticaria were lower in the group of infants fed with a formula with either an added mixture of FOS and GOS compared to the placebo group. Furthermore, in a prospective, double-blind, and placebo-controlled fashion, a mixture of neutral prebiotic oligosaccharides was evaluated for protective effect against allergy. A total of 92 healthy infants at risk of atopy were fed either a placebo-supplemented (0.8 g/100 mL maltodextrin) hypoallergenic formula or prebiotic-supplemented (0.8 g/100 mL short-chain GOS/long-chain FOS) during the first 6 months of life. The authors concluded that feeding infants with oligosaccharide prebiotics (short-chain GOS/long-chain FOS) early in life protects against atopic dermatitis and allergic rhinoconjunctivitis.Citation115

However, in a Cochrane study, Osborn and SinnCitation116 found that prebiotic supplementation in infant formula does not prevent food hypersensitivity or allergic disease. In addition, prebiotics alone are inferior to synbiotics in the treatment of moderate-to-severe childhood atopic dermatitis.Citation117

Combined prebiotics and probiotics in the prevention of allergic disease

The effect of early intervention with synbiotics, a combination of probiotics and prebiotics, on the prevalence of asthma-like symptoms in infants with high risk of allergic diseases has been investigated. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial, 90 infants with atopic dermatitis, age <7 months, were randomized to receive an infant formula with GOS/FOS and B. breve M16V mixture or formula without synbiotics; 75 children completed the 1-year follow-up, and the study showed that the prevalence of wheezing was substantially lower in the synbiotic than in the placebo group.Citation118 However, other studies showed that synbiotic has no benefit on the cumulative occurrence of allergic diseases, but was useful in reducing IgE-associated (atopic) diseases and the occurrence of atopic eczema.Citation41,Citation119

Modified milk formulas during early life

Several health care practitioners recommend the use of soy-based formulas to treat infants with allergy or food intolerance. However, this is not currently recommended for prevention of allergy or food intolerance.Citation120 However, other formulas, such as hydrolyzed formulas, have been proposed for the prevention of allergy and food intolerance in infants.Citation121 Hydrolyzed formulas consist of cow’s milk proteins that undergo enzymatic and chemical hydrolysis to decrease the peptide size, molecular weight, and allergenicity of the proteins.Citation122 It has been postulated that when breastfeeding alone is not feasible in high-risk infants, partially hydrolyzed (casein- or whey-based) formulas are effective in preventing allergic diseases, particularly atopic dermatitis. In a systematic review, Alexander and CabanaCitation123 reviewed 18 articles to study the role of partially hydrolyzed 100% whey (pHF-W) protein infant formula in reducing the risk of atopic dermatitis. The study showed that feeding with pHF-W statistically significantly decreased the risk of atopic manifestations (summary relative-risk estimate 0.56, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.40–0.77). The authors concluded that exclusive breast-feeding should be the first choice of infant nutrition in the first 6 months of life. However, for infants who are not exclusively breast-fed, feeding with pHF-W instead of cow’s milk formula reduces the risk of atopic dermatitis in those with a family history of allergy. Moreover, Szajewska and HorvathCitation124 conducted a meta-analysis to study the evidence of a pHF-W formula in the prevention of allergic diseases. The authors concluded that for all allergic diseases and atopic eczema/atopic dermatitis, the use of the pHF compared with standard formula decreased the risk of allergy in high-risk children. However, in a Cochrane systematic review, Osborn and SinnCitation121 concluded that compared to exclusive breast-feeding, alimenting with hydrolyzed formula in the early days of infancy resulted in no significant difference in childhood cow’s milk allergy or infant allergy. With regard to extensively hydrolyzed (casein-or whey-based) formulas, the literature indicates that they are effective for primary prevention of allergy in high-risk infants, but they are not cost-effective when compared with partially hydrolyzed formulas.Citation125

Dietary patterns (Mediterranean diet)

Changes in dietary customs play an important role in the prevalence of symptoms of allergic diseases.Citation126–Citation132 The Western diet constitutes a high intake of processed and red meat, fast food, sugary drinks, and full-fat dairy products, with minimal vegetables. This diet pattern contains high levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) and ω6 fatty acids, which are risk factors for some chronic and allergic diseases.Citation133,Citation134 Meanwhile, the Mediterranean diet comprises increased use of unrefined grain, fruits, and vegetables, moderate utilization of dairy products and milk, and low meat intake.Citation135 Several studies have mentioned the protective role the Mediterranean diet plays in some chronic diseases and allergies,Citation133,Citation135–Citation138 perhaps due to its antioxidant and immunoregulatory properties.Citation139

For instance, de Batlle et alCitation137 conducted a cross-sectional study that included 1,476 Mexican children (6–7 years old). Nutritional data of the children’s intake in the previous 12 months and their mothers’ intake during pregnancy were gathered. The study showed that maintaining a Mediterranean diet was inversely associated with wheezing ever (odds ratio [OR] =0.64, 95% CI: 0.47–0.87), asthma ever (OR =0.60, 95% CI: 0.40–0.91), rhinitis ever (OR =0.41, 95% CI: 0.22–0.77), sneezing ever (OR =0.79, 95% CI: 0.59–1.07), and itchy/watery eyes (OR =0.63, 95% CI: 0.42–0.95). Chatzi and KogevinasCitation133 echoed those results, and concluded that maintaining a Mediterranean diet in the early years can have a protective effect on the development of asthma and atopy in children. For older children, Arvaniti et alCitation136 included in his study 700 children 10–12 years old from 18 schools located in Athens, Greece. The authors concluded that adherence to a Mediterranean diet was inversely linked to the likelihood of asthma symptoms. Moreover, in a study conducted on adults showed that adherence to the Mediterranean diet reduced the risk of uncontrolled asthma by 78% (OR =0.22, 95% CI: 0.05–0.85; P=0.028).Citation139

In a meta-analysis and systematic review, Garcia-Marcos et alCitation140 studied the influence of the Mediterranean diet on asthma in children. The outcomes measured were prevalence of “current wheeze”, “current severe wheeze”, or “asthma ever”. The authors used ORs to compare the highest tertile of the scores with the lowest. In addition, random-effect meta-analyses for the whole group of studies were used and stratified by Mediterranean setting (centers <100 km from the Mediterranean coast). The study concluded that following a Mediterranean diet is associated with lower prevalence of “asthma ever” (OR =0.86, 95% CI: 0.78–0.95, P=0.004 [all]; OR =0.86, 95% CI: 0.74–1.01, P=0.06 [Mediterranean]; OR =0.86, 95% CI: 0.75–0.98, P=0.027 [non-Mediterranean]), “current wheeze” (OR =0.85, 95% CI: 0.75–0.98; P=0.02), driven by Mediterranean centers (OR =0.79, 95% CI: 0.66–0.94; P=0.009), and “current severe wheeze” (OR =0.82, 95% CI: 0.55–1.22, P=0.330 [all]; OR =0.66, 95% CI: 0.48–0.90, P=0.008 [Mediterranean]; and OR =0.99, 95% CI: 0.79–1.25, P=0.95 [non-Mediterranean]; with the difference between regions being significant). However, Tamay et alCitation141 concluded in their large study that the protective effect of the Mediterranean diet on allergic rhinitis in elementary school children was not significant.

Micronutrients

As Hippocrates famously noted, “Let food be thy medicine”. Perhaps the factors with the greatest effect on modulating atopic expression are nutritional in nature. For those at risk, exposure to certain foods may contribute to severe, lifelong asthma or food allergies. Other foods, rich in anti-inflammatory antioxidants, may in fact ameliorate allergic responses to environmental stimuli. It is unlikely to be one factor that is solely responsible for unlocking genomic tendencies toward atopy.Citation142

An association between seasonal allergies and food allergies has been reported. In some individuals, allergic rhinitis due to specific pollens is connected to oral allergy symptoms due to certain fruits and vegetables.Citation143 Interestingly, organic versions of these same foods may be tolerated by patients who experience reactions with conventional produce. It may be that the pesticide stimulation of the immune system is responsible for this difference, or it may be that the level of antioxidant nutrients in organic foods is more concentrated.Citation144 There is no clear evidence on the role of vitamins A or C in primary prevention of allergic diseases. However, vitamin D in particular is of increasing interest in atopic prevention and treatment. A growing number of studies have consistently demonstrated that a majority of children are vitamin D-insufficient or -deficient. In children with asthma and allergic diseases, vitamin D deficiency is a strong correlate for asthma, allergic rhinitis, and wheezing.Citation145 Furthermore, research indicates that vitamin D deficiency functions as a strong predictor of asthma in children.Citation146–Citation148

In a Cochrane study conducted by Bath-Hextall et al,Citation149 the authors assessed the following micronutrients once thought to be protective against eczema: sunflower oil (linoleic acid) versus fish oil versus placebo, docosahexaenoic acid versus control, oral zinc sulfate compared to placebo, vitamin D versus placebo, vitamin D versus vitamin E versus vitamins D plus E together versus placebo, pyridoxine versus placebo, sea buckthorn seed oil versus sea buckthorn pulp oil versus placebo, selenium versus selenium plus vitamin E versus placebo, and hempseed oil versus placebo. The study concluded that there was no conclusive evidence of the benefit of dietary supplements in eczema.

Essential fatty acids

More recent studies have looked at the role of essential fatty acids in reducing allergic disease. The evidence is very good for prenatal prevention of atopy when mothers ingest higher amounts of ω3 PUFAs.Citation150 It also appears that newborns who ingest breast milk relatively rich in ω3 are less likely to develop allergic symptoms.Citation151,Citation152 This effect is most prominent in those babies at highest risk genetically for allergic diseases. Interestingly, the results of directly feeding infants PUFAs are not as clear. Studies of dietary modification with ω3 PUFAs in children at high risk demonstrated reduction in atopy.Citation153,Citation154 Perhaps it is the balance of the two that is most important, and one must also take into account preexisting dietary deficiencies and genomic factors. More research is clearly needed in this realm before universal recommendations can be made.

Conclusion and recommendations

Multiple, recent, and large epidemiological studies have confirmed the beneficial effects of breast-feeding in reducing the risk of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic eczema among children. Breast milk constitutes a major source of support to gut colonization, due to its bifidobacteria content and by providing a large amount of GOS, which selectively accelerate the growth of bifidobacteria. The literature lacks consensus in recommending the addition of probiotics to foods for prevention and treatment of allergic diseases. Moreover, probiotics must not be provided to immunocompromised children. Despite many studies portraying safety and efficacy in the use of probiotics during pregnancy and lactation, more evidence is required before a strong recommendation can be made. Probiotics in infant formula are safe. However, more RCTs are needed to compare human milk versus infant formula supplemented with probiotics.

Prebiotics may prove to be effective in reducing atopy in healthy children. Prebiotics in infant formula have been found to be safe, but clinical efficacy has to be investigated more, not to mention the high cost burden on families. There is insufficient evidence to support soy formulas or amino acid formulas for prevention of allergic disease. Partially hydrolyzed formulas are of use in infants at high risk of atopic dermatitis in the first 6 months of life instead of intact cow’s milk protein formula. A healthy diet, such as the Mediterranean diet, may have a protective effect on the development of asthma and atopy in children. In children with asthma and allergic diseases, vitamin D deficiency is a strong correlate for asthma, allergic rhinitis, and wheezing. It is worth mentioning that the current deficiency of evidence of efficacy does not mean that future clinical investigations will not establish tangible health benefits for probiotics, prebiotics, diet, and vitamin supplementation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Hamad Medical Corporation for the support and ethical approval (HMC Research Protocol No. 15455/15).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- WestlyEGenetics: seeking a gene genieNature20114797374S10S11

- ShurinMRSmolkinYSImmune-mediated diseases: where do we stand?Adv Exp Med Biol200760131217712987

- MasoliMFabianDHoltSBeasleyRThe global burden of asthma Available from: http://www.ginasthma.org/local/uploads/files/GINABurdenReport_1.pdfAccessed July 17, 2015

- International Study of Asthma and Allergies in ChildhoodThe Global Asthma Report 2011ParisInternational Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease2011 Available from: http://isaac.auckland.ac.nz/resources/Global_Asthma_Report_2011.pdfAccessed: January 11, 2016

- SorianoJBCamposHSEpidemiology of asthma2012 Available from: http://www.sopterj.com.br/profissionais/_revista/2012/n_02/03.pdfAccessed: January 11, 2016

- HongSSonDKLimWRThe prevalence of atopic dermatitis, asthma, and allergic rhinitis and the comorbidity of allergic diseases in childrenEnviron Health Toxicol201227e201200622359737

- MeltzerEOBuksteinDAThe economic impact of allergic rhinitis and current guidelines for treatmentAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol20111062 SupplS12S1621277528

- CivelekESahinerUMYükselHPrevalence, burden, and risk factors of atopic eczema in schoolchildren aged 10–11 years: a national multicenter studyJ Investig Allergol Clin Immunol2011214270277

- American Lung AssociationTrends in asthma morbidity and mortality2012 Available from: http://www.lung.org/finding-cures/our-research/trend-reports/asthma-trend-report.pdfAccessed July 17, 2015

- HollowayJWYangIAHolgateSTGenetics of allergic diseaseJ Allergy Clin Immunol20101252 Suppl 2S81S9420176270

- GuilbertTWDenlingerLCRole of infection in the development and exacerbation of asthmaExpert Rev Respir Med201041718320305826

- AsherMIStewartAWMallolJWhich population level environmental factors are associated with asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis and eczema? Review of the ecological analyses of ISAAC Phase OneRespir Res201011820092649

- NishimuraKKGalanterJMRothLAEarly life air pollution and asthma risk in minority children: the GALA II & SAGE II studiesAm J Respir Crit Care Med2013188330931823750510

- World Health OrganizationPrevention of allergy and allergic asthma2003 Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2003/WHO_NMH_MNC_CRA_03.2.pdf?ua=1Accessed July 17, 2015

- RigonGValloneCLucantoniVSignoreFMaternal factors pre- and during delivery contribute to gut microbiota shaping in newbornsFront Cell Infect Microbiol201229322919684

- AzadMBKonyaTMaughanHGut microbiota of healthy Canadian infants: profiles by mode of delivery and infant diet at 4 monthsCMAJ2013185538539423401405

- WallRRossRPRyanCARole of gut microbiota in early infant developmentClin Med Pediatr20093455423818794

- GrönlundMMGrześkowiakLIsolauriESalminenSInfluence of mother’s intestinal microbiota on gut colonization in the infantGut Microbes20112422723321983067

- MorelliLPostnatal development of intestinal microflora as influenced by infant nutritionJ Nutr20081389S1791S1795

- HongPYLeeBWAwMComparative analysis of fecal microbiota in infants with and without eczemaPLoS One201054e996420376357

- AvershinaEStorrøOØienTBifidobacterial succession and correlation networks in a large unselected cohort of mothers and their childrenAppl Environ Microbiol201379249750723124244

- GrönlundMMLehtonenOPEerolaEKeroPFecal microflora in healthy infants born by different methods of delivery: permanent changes in intestinal flora after cesarean deliveryJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr199928119259890463

- KolokotroniOMiddletonNGavathaMLamnisosDPriftisKNYiallourosPKAsthma and atopy in children born by caesarean section: effect modification by family history of allergies – a population based cross-sectional studyBMC Pediatr20121217923153011

- AzizQDoréJEmmanuelAGuarnerFQuigleyEMGut microbiota and gastrointestinal health: current concepts and future directionsNeurogastroenterol Motil201325141523279728

- KauALAhernPPGriffinNWGoodmanALGordonJIHuman nutrition, the gut microbiome and the immune systemNature2011474735132733621677749

- GroerMWLucianoAADishawLJAshmeadeTLMillerEGilbertJADevelopment of the preterm infant gut microbiome: a research priorityMicrobiome201423825332768

- Di MauroANeuJRiezzoGGastrointestinal function development and microbiotaItal J Pediatr2013391523433508

- MazmanianSKLiuCHTzianabosAOKasperDLAn immunomodulatory molecule of symbiotic bacteria directs maturation of the host immune systemCell2005122110711816009137

- GhadimiDFölster-HolstRde VreseMWinklerPHellerKJSchrezenmeirJEffects of probiotic bacteria and their genomic DNA on TH1/TH2-cytokine production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of healthy and allergic subjectsImmunobiology2008213867769218950596

- MatsuzakiTTakagiAIkemuraHMatsuguchiTYokokuraTIntestinal microflora: probiotics and autoimmunityJ Nutr20071373 Suppl 2798S802S17311978

- PendersJThijsCvan den BrandtPAGut microbiota composition and development of atopic manifestations in infancy: the KOALA birth cohort studyGut200756566166717047098

- MelliLCdo Carmo-RodriguesMSAraújo-FilhoHBSoléDde MoraisMBIntestinal microbiota and allergic diseases: a systematic reviewAllergol Immunopathol (Madr) Epub2015515

- KimJYKwonJHAhnSHEffect of probiotic mix (Bifidobacterium bifidum, Bifidobacterium lactis, Lactobacillus acidophilus) in the primary prevention of eczema: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trialPediatr Allergy Immunol2010212 Pt 2e386e39319840300

- RautavaSKainonenESalminenSIsolauriEMaternal probiotic supplementation during pregnancy and breast-feeding reduces the risk of eczema in the infantJ Allergy Clin Immunol201213061355136023083673

- GarridoDDallasDCMillsDAConsumption of human milk glycoconjugates by infant-associated bifidobacteria: mechanisms and implicationsMicrobiology2013159Pt 464966423460033

- MikamiKKimuraMTakahashiHInfluence of maternal bifidobacteria on the development of gut bifidobacteria in infantsPharmaceuticals (Basel)20125662964224281665

- EhlayelMSBenerADuration of breast-feeding and the risk of childhood allergic diseases in a developing countryAllergy Asthma Proc200829438639118702886

- SimonsEDellSDBeyeneJToTShahPSIs breastfeeding protective against the development of asthma or wheezing in children? A systematic review and meta-analysisAllergy Asthma Clin Immunol20117Suppl 2A11

- Al-MakoshiAAl-FrayhATurnerSDevereuxGBreastfeeding practice and its association with respiratory symptoms and atopic disease in 1-3-year-old children in the city of Riyadh, central Saudi ArabiaBreastfeed Med20138112713323039399

- SalminenSBouleyCBoutron-RuaultMCFunctional food science and gastrointestinal physiology and functionBr J Nutr199880Suppl 1S147S1719849357

- ThomasDWGreerFRProbiotics and prebiotics in pediatricsPediatrics201012661217123121115585

- European Food and Feed Cultures AssociationFood culture: definition of food cultures (FC)2015 Available from: http://www.effca.org/content/food-cultureAccessed January 11, 2015

- AshwellMConcepts of Functional FoodsBrusselsInternational Life Sciences Institute2002 Available from: http://www.ilsi.org/Publications/01_Ashwell_ILSIFuncFoods2002.pdfAccessed January 11, 2015

- FooksLJGibsonGRProbiotics as modulators of the gut floraBr J Nutr200288Suppl 1S39S4912215180

- HeymanMMenardSProbiotic microorganisms: how they affect intestinal pathophysiologyCell Mol Life Sci20025971151116512222962

- IsolauriESalminenSOuwehandACMicrobial-gut interactions in health and disease. ProbioticsBest Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol200418229931315123071

- ManningTSGibsonGRMicrobial-gut interactions in health and disease. PrebioticsBest Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol200418228729815123070

- KolidaSTuohyKGibsonGRPrebiotic effects of inulin and oligofructoseBr J Nutr200287Suppl 2S193S19712088518

- KimCHParkJKimMGut microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids, T cells, and inflammationImmune Netw20141462778825550694

- Gourgue-JeannotCKalmokoffMLKheradpirEDietary fructooligosaccharides alter the cultivable faecal population of rats but do not stimulate the growth of intestinal bifidobacteriaCan J Microbiol2006521092493317110960

- ArslanogluSMoroGEBoehmGEarly supplementation of prebiotic oligosaccharides protects formula-fed infants against infections during the first 6 months of lifeJ Nutr2007137112420242417951479

- ShadidRHaarmanMKnolJEffects of galactooligosaccharide and long-chain fructooligosaccharide supplementation during pregnancy on maternal and neonatal microbiota and immunity – a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studyAm J Clin Nutr20078651426143717991656

- SteedHMacfarlaneGTMacfarlaneSPrebiotics, synbiotics and inflammatory bowel diseaseMol Nutr Food Res200852889890518383235

- ShimizuKOguraHAsaharaTProbiotic/synbiotic therapy for treating critically ill patients from a gut microbiota perspectiveDig Dis Sci2013581233222903218

- BlümerNSelSVirnaSPerinatal maternal application of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG suppresses allergic airway inflammation in mouse offspringClin Exp Allergy200737334835717359385

- FeleszkoWJaworskaJRhaRDProbiotic-induced suppression of allergic sensitization and airway inflammation is associated with an increase of T regulatory-dependent mechanisms in a murine model of asthmaClin Exp Allergy200737449850517430345

- RigauxPDanielCHisberguesMImmunomodulatory properties of Lactobacillus plantarum and its use as a recombinant vaccine against mite allergyAllergy200964340641419120072

- RepaAGrangetteCDanielCMucosal co-application of lactic acid bacteria and allergen induces counter-regulatory immune responses in a murine model of birch pollen allergyVaccine2003221879514604575

- ForsythePInmanMDBienenstockJOral treatment with live Lactobacillus reuteri inhibits the allergic airway response in miceAm J Respir Crit Care Med2007175656156917204726

- KarimiKInmanMDBienenstockJForsythePLactobacillus reuteri-induced regulatory T cells protect against an allergic airway response in miceAm J Respir Crit Care Med2009179318619319029003

- StockertKSchneiderBPorentaGRathRNisselHEichlerILaser acupuncture and probiotics in school age children with asthma: a randomized, placebo-controlled pilot study of therapy guided by principles of traditional Chinese medicinePediatr Allergy Immunol200718216016617338790

- MoreiraAKekkonenRKorpelaRDelgadoLHaahtelaTAllergy in marathon runners and effect of Lactobacillus GG supplementation on allergic inflammatory markersRespir Med200710161123113117196811

- HelinTHaahtelaSHaahtelaTNo effect of oral treatment with an intestinal bacterial strain, Lactobacillus rhamnosus (ATCC 53103), on birch-pollen allergy: a placebo-controlled double-blind studyAllergy200257324324611906339

- VliagoftisHKouranosVDBetsiGIFalagasMEProbiotics for the treatment of allergic rhinitis and asthma: systematic review of randomized controlled trialsAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol2008101657057919119700

- ViljanenMSavilahtiEHaahtelaTProbiotics in the treatment of atopic eczema/dermatitis syndrome in infants: a double-blind placebo-controlled trialAllergy200560449450015727582

- WickensKBlackPNStanleyTVA differential effect of 2 probiotics in the prevention of eczema and atopy: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trialJ Allergy Clin Immunol2008122478879418762327

- RosenfeldtVBenfeldtENielsenSDEffect of probiotic Lactobacillus strains in children with atopic dermatitisJ Allergy Clin Immunol2003111238939512589361

- BetsiGIPapadavidEFalagasMEProbiotics for the treatment or prevention of atopic dermatitis: a review of the evidence from randomized controlled trialsAm J Clin Dermatol2008929310318284263

- DoegeKGrajeckiDZyriaxBCDetinkinaEEulenburgCBuhlingKJImpact of maternal supplementation with probiotics during pregnancy on atopic eczema in childhood – a meta-analysisBr J Nutr201210711621787448

- PelucchiCChatenoudLTuratiFProbiotics supplementation during pregnancy or infancy for the prevention of atopic dermatitis: a meta-analysisEpidemiology201223340241422441545

- HanYKimBBanJA randomized trial of Lactobacillus plantarum CJLP133 for the treatment of atopic dermatitisPediatr Allergy Immunol201223766767323050557

- KalliomakiMSalminenSPoussaTArvilommiHIsolauriEProbiotics and prevention of atopic disease: 4-year follow-up of a randomised placebo-controlled trialLancet200336193721869187112788576

- KoppMVSalfeldPProbiotics and prevention of allergic diseaseCurr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care200912329830319318939

- TaylorALDunstanJAPrescottSLProbiotic supplementation for the first 6 months of life fails to reduce the risk of atopic dermatitis and increases the risk of allergen sensitization in high-risk children: a randomized controlled trialJ Allergy Clin Immunol2007119118419117208600

- GoreCCustovicATannockGWTreatment and secondary prevention effects of the probiotics Lactobacillus paracasei or Bifidobacterium lactis on early infant eczema: randomized controlled trial with follow-up until age 3 yearsClin Exp Allergy201242111212222092692

- PrescottSLBjörksténBProbiotics for the prevention or treatment of allergic diseasesJ Allergy Clin Immunol2007120225526217544096

- OsbornDASinnJKProbiotics in infants for prevention of allergic disease and food hypersensitivityCochrane Database Syst Rev20074CD00647517943912

- BoyleRJBath-HextallFJLeonardi-BeeJMurrellDFTangMLProbiotics for the treatment of eczema: a systematic reviewClin Exp Allergy20093981117112719573037

- BoyleRJBath-HextallFJLeonardi-BeeJMurrellDFTangMLProbiotics for treating eczemaCochrane Database Syst Rev20084CD00613518843705

- LeeJSetoDBieloryLMeta-analysis of clinical trials of probiotics for prevention and treatment of pediatric atopic dermatitisJ Allergy Clin Immunol20081211116121.e1118206506

- KalliomäkiMSalminenSPoussaTIsolauriEProbiotics during the first 7 years of life: a cumulative risk reduction of eczema in a randomized, placebo-controlled trialJ Allergy Clin Immunol200711941019112117289135

- KoppMVHennemuthIHeinzmannAUrbanekRRandomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of probiotics for primary prevention: no clinical effects of Lactobacillus GG supplementationPediatrics20081214e850e85618332075

- DotterudCKStorrøOJohnsenRØienTProbiotics in pregnant women to prevent allergic disease: a randomized, double-blind trialBr J Dermatol2010163361662320545688

- PendersJStobberinghEEvan den BrandtPAThijsCThe role of the intestinal microbiota in the development of atopic disordersAllergy200762111223123617711557

- PengGCHsuCHThe efficacy and safety of heat-killed Lactobacillus paracasei for treatment of perennial allergic rhinitis induced by house-dust mitePediatr Allergy Immunol200516543343816101937

- IvoryKChambersSJPinCPrietoEArquésJLNicolettiCOral delivery of Lactobacillus casei Shirota modifies allergen-induced immune responses in allergic rhinitisClin Exp Allergy20083881282128918510694

- FeliceGBarlettaBButteroniCUse of probiotic bacteria for prevention and therapy of allergic diseases: studies in mouse model of allergic sensitizationJ Clin Gastroenterol200842Suppl 3 Pt 1S130S13218806704

- GiovanniniMAgostoniCRivaEA randomized prospective double blind controlled trial on effects of long-term consumption of fermented milk containing Lactobacillus casei in pre-school children with allergic asthma and/or rhinitisPediatr Res200762221522017597643

- KuitunenMKukkonenKJuntunen-BackmanKProbiotics prevent IgE-associated allergy until age 5 years in cesarean-delivered children but not in the total cohortJ Allergy Clin Immunol2009123233534119135235

- WickensKBlackPStanleyTVA protective effect of Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 against eczema in the first 2 years of life persists to age 4 yearsClin Exp Allergy20124271071107922702506

- KawaseMHeFKubotaAEffect of fermented milk prepared with two probiotic strains on Japanese cedar pollinosis in a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical studyInt J Food Microbiol2009128342943418977549

- MoritaHHeFKawaseMPreliminary human study for possible alteration of serum immunoglobulin E production in perennial allergic rhinitis with fermented milk prepared with Lactobacillus gasseri TMC0356Microbiol Immunol200650970170616985291

- XiaoJZKondoSYanagisawaNEffect of probiotic Bifidobacterium longum BB536 [corrected] in relieving clinical symptoms and modulating plasma cytokine levels of Japanese cedar pollinosis during the pollen season: a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trialJ Investig Allergol Clin Immunol20061628693

- XiaoJZKondoSYanagisawaNProbiotics in the treatment of Japanese cedar pollinosis: a double-blind placebo-controlled trialClin Exp Allergy200636111425143517083353

- TamuraMShikinaTMorihanaTEffects of probiotics on allergic rhinitis induced by Japanese cedar pollen: randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trialInt Arch Allergy Immunol20071431758217199093

- IsolauriERautavaSKalliomäkiMKirjavainenPSalminenSRole of probiotics in food hypersensitivityCurr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol20022326327112045425

- BarlettaBRossiGSchiaviEProbiotic VSL#3-induced TGF-β ameliorates food allergy inflammation in a mouse model of peanut sensitization through the induction of regulatory T cells in the gut mucosaMol Nutr Food Res201357122233224423943347

- ShidaKTakahashiRIwadateELactobacillus casei strain Shirota suppresses serum immunoglobulin E and immunoglobulin G1 responses and systemic anaphylaxis in a food allergy modelClin Exp Allergy200232456357011972603

- IsolauriEArvolaTSütasYMoilanenESalminenSProbiotics in the management of atopic eczemaClin Exp Allergy200030111604161011069570

- HolJvan LeerEHElink SchuurmanBEThe acquisition of tolerance toward cow’s milk through probiotic supplementation: a randomized, controlled trialJ Allergy Clin Immunol200812161448145418436293

- SohSEAwMGerezIProbiotic supplementation in the first 6 months of life in at risk Asian infants – effects on eczema and atopic sensitization at the age of 1 yearClin Exp Allergy200939457157819134020

- ShanahanFA commentary on the safety of probioticsGastroenterol Clin North Am201241486987623101692

- FedorakRNMadsenKLProbiotics and prebiotics in gastrointestinal disordersCurr Opin Gastroenterol200420214615515703637

- BorrielloSPHammesWPHolzapfelWSafety of probiotics that contain lactobacilli or bifidobacteriaClin Infect Dis200336677578012627362

- MackayADTaylorMBKibblerCCHamilton-MillerJMLactobacillus endocarditis caused by a probiotic organismClin Microbiol Infect19995529029211856270

- RautioMJousimies-SomerHKaumaHLiver abscess due to a Lactobacillus rhamnosus strain indistinguishable from L. rhamnosus strain GGClin Infect Dis19992851159116010452653

- AllenSJJordanSStoreyMDietary supplementation with lactobacilli and bifidobacteria is well tolerated and not associated with adverse events during late pregnancy and early infancyJ Nutr2010140348348820089774

- Martin-MuñozMFFortuniMCaminoaMBelverTQuirceSCaballeroTAnaphylactic reaction to probiotics: cow’s milk and hen’s egg allergens in probiotic compoundsPediatr Allergy Immunol201223877878422957765

- RobinFPaillardCMarchandinHDemeocqFBonnetRHennequinCLactobacillus rhamnosus meningitis following recurrent episodes of bacteremia in a child undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantationJ Clin Microbiol201048114317431920844225

- VahabnezhadEMochonABWozniakLJZiringDALactobacillus bacteremia associated with probiotic use in a pediatric patient with ulcerative colitisJ Clin Gastroenterol201347543743923426446

- LuongMLSareyyupogluBNguyenMHLactobacillus probiotic use in cardiothoracic transplant recipients: a link to invasive Lactobacillus infection?Transpl Infect Dis201012656156421040283

- CabanaMDShaneALChaoCOliva-HemkerMProbiotics in primary care pediatricsClin Pediatr (Phila)200645540541016891272

- DaiMLuJWangYLiuZYuanZIn vitro development and transfer of resistance to chlortetracycline in Bacillus subtilisJ Microbiol201250580781223124749

- ArslanogluSMoroGESchmittJTandoiLRizzardiSBoehmGEarly dietary intervention with a mixture of prebiotic oligosaccharides reduces the incidence of allergic manifestations and infections during the first two years of lifeJ Nutr200813861091109518492839

- ArslanogluSMoroGEBoehmGWienzFStahlBBertinoEEarly neutral prebiotic oligosaccharide supplementation reduces the incidence of some allergic manifestations in the first 5 years of lifeJ Biol Regul Homeost Agents2012263 Suppl495923158515

- OsbornDASinnJKPrebiotics in infants for prevention of allergyCochrane Database Syst Rev20133CD00647423543544

- WuKGLiTHPengHJLactobacillus salivarius plus fructo-oligosaccharide is superior to fructo-oligosaccharide alone for treating children with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a double-blind, randomized, clinical trial of efficacy and safetyBr J Dermatol2012166112913621895621

- van der AaLBvan AalderenWMHeymansHSSynbiotics prevent asthma-like symptoms in infants with atopic dermatitisAllergy201166217017720560907

- KukkonenKSavilahtiEHaahtelaTLong-term safety and impact on infection rates of postnatal probiotic and prebiotic (synbiotic) treatment: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialPediatrics2008122181218595980

- OsbornDASinnJSoy formula for prevention of allergy and food intolerance in infantsCochrane Database Syst Rev20043CD00374115266499

- OsbornDASinnJFormulas containing hydrolysed protein for prevention of allergy and food intolerance in infantsCochrane Database Syst Rev20034CD00366414583987

- LoweAJDharmageSCAllenKJTangMLHillDJThe role of partially hydrolyzed whey formula for the prevention of allergic disease: evidence and gapsExpert Rev Clin Immunol201391314123256762

- AlexanderDDCabanaMDPartially hydrolyzed 100% whey protein infant formula and reduced risk of atopic dermatitis: a meta-analysisJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr201050442243020216095

- SzajewskaHHorvathAMeta-analysis of the evidence for a partially hydrolyzed 100% whey formula for the prevention of allergic diseasesCurr Med Res Opin201026242343720001576

- SuJPrescottSSinnJCost-effectiveness of partially-hydrolyzed formula for prevention of atopic dermatitis in AustraliaJ Med Econ20121561064107722630113

- FoliakiSPearceNBjörksténBMallolJMontefortSvon MutiusEAntibiotic use in infancy and symptoms of asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in children 6 and 7 years old: International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood Phase IIIJ Allergy Clin Immunol2009124598298919895986

- Batlles-GarridoJTorres-BorregoJRubí-RuizTPrevalence and factors linked to allergic rhinitis in 10 and 11-year-old children in Almeria. ISAAC Phase II, SpainAllergol Immunopathol (Madr)201038313514120462685

- MagnussonJKullIRosenlundHFish consumption in infancy and development of allergic disease up to age 12 yAm J Clin Nutr20139761324133023576046

- SeoJHKwonSOLeeSYAssociation of antioxidants with allergic rhinitis in children from SeoulAllergy Asthma Immunol Res201352818723450181

- MoyesCDClaytonTPearceNTime trends and risk factors for rhinoconjunctivitis in New Zealand children: an International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) surveyJ Paediatr Child Health2012481091392022897723

- PenarandaAAristizabalGGarciaEVásquezCRodríguez-MartinezCERhinoconjunctivitis prevalence and associated factors in school children aged 6–7 and 13–14 years old in Bogota, ColombiaInt J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol201276453053522301354

- BeasleyRClaytonTCraneJAssociation between paracetamol use in infancy and childhood, and risk of asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in children aged 6–7 years: analysis from Phase Three of the ISAAC programmeLancet200837296431039104818805332

- ChatziLKogevinasMPrenatal and childhood Mediterranean diet and the development of asthma and allergies in childrenPublic Health Nutr2009129A1629163419689832

- MeyerhardtJANiedzwieckiDHollisDAssociation of dietary patterns with cancer recurrence and survival in patients with stage III colon cancerJAMA2007298775476417699009

- PsaltopoulouTNaskaAOrfanosPTrichopoulosDMountokalakisTTrichopoulouAOlive oil, the Mediterranean diet, and arterial blood pressure: the Greek European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) studyAm J Clin Nutr20048041012101815447913

- ArvanitiFPriftisKNPapadimitriouASalty-snack eating, television or video-game viewing, and asthma symptoms among 10- to 12-year-old children: the PANACEA studyJ Am Diet Assoc2011111225125721272699

- de BatlleJGarcia-AymerichJBarraza-VillarrealAAntóJMRomieuIMediterranean diet is associated with reduced asthma and rhinitis in Mexican childrenAllergy200863101310131618782109

- ChatziLApostolakiGBibakisIProtective effect of fruits, vegetables and the Mediterranean diet on asthma and allergies among children in CreteThorax200762867768317412780

- BarrosRMoreiraAFonsecaJAdherence to the Mediterranean diet and fresh fruit intake are associated with improved asthma controlAllergy200863791792318588559

- Garcia-MarcosLCastro-RodriguezJAWeinmayrGPanagiotakosDBPriftisKNNagelGInfluence of Mediterranean diet on asthma in children: a systematic review and meta-analysisPediatr Allergy Immunol201324433033823578354

- TamayZAkcayAErginAGülerNDietary habits and prevalence of allergic rhinitis in 6 to 7-year-old schoolchildren in TurkeyAllergol Int201463455356225056225

- WegenerG‘Let food be thy medicine, and medicine be thy food’: Hippocrates revisitedActa Neuropsychiatr20142611325279413

- JerschowEMcGinnAPde VosGDichlorophenol-containing pesticides and allergies: results from the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005–2006Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol2012109642042523176881

- American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Types of food allergy: oral allergy syndrome2014 Available from: http://acaai.org/allergies/types/food-allergies/types-food-allergy/oral-allergy-syndromeAccessed July 2, 2015

- BenerAEhlayelMSBenerZHHamidQThe impact of vitamin D deficiency on asthma, allergic rhinitis and wheezing in children: an emerging public health problemJ Family Community Med201421315416125374465

- BenerAEhlayelMSTulicMKHamidQVitamin D deficiency as a strong predictor of asthma in childrenInt Arch Allergy Immunol2012157216817521986034

- RovnerAJO’BrienKOHypovitaminosis D among healthy children in the United States: a review of the current evidenceArch Pediatr Adolesc Med2008162651351918524740

- LitonjuaAAChildhood asthma may be a consequence of vitamin D deficiencyCurr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol20099320220719365260

- Bath-HextallFJJenkinsonCHumphreysRWilliamsHCDietary supplements for established atopic eczemaCochrane Database Syst Rev20122CD00520522336810

- DenburgJAHatfieldHMCyrMMFish oilPediatr Res200557227628115585690

- WijgaAHvan HouwelingenACKerkhofMBreast milk fatty acids and allergic disease in preschool children: the Prevention and Incidence of Asthma and Mite Allergy birth cohort studyJ Allergy Clin Immunol2006117244044716461146

- OddyWHPalSKuselMMAtopy, eczema and breast milk fatty acids in a high-risk cohort of children followed from birth to 5 yrPediatr Allergy Immunol200617141016426248

- PeatJKMihrshahiSKempASThree-year outcomes of dietary fatty acid modification and house dust mite reduction in the Childhood Asthma Prevention StudyJ Allergy Clin Immunol2004114480781315480319

- MihrshahiSPeatJKWebbKOddyWMarksGBMellisCMEffect of omega-3 fatty acid concentrations in plasma on symptoms of asthma at 18 months of agePediatr Allergy Immunol200415651752215610365