Abstract

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a common, complex, and difficult to treat chronic widespread pain disorder, which usually requires a multidisciplinary approach using both pharmacological and non-pharmacological (education and exercise) interventions. It is a condition of heightened generalized sensitization to sensory input presenting as a complex of symptoms including pain, sleep dysfunction, and fatigue, where the pathophysiology could include dysfunction of the central nervous system pain modulatory systems, dysfunction of the neuroendocrine system, and dysautonomia. A cyclic model of the pathophysiological processes is compatible with the interrelationship of primary symptoms and the array of postulated triggers associated with FM. Many of the molecular targets of current and emerging drugs used to treat FM have been focused to the management of discrete symptoms rather than the condition. Recently, drugs (eg, pregabalin, duloxetine, milnacipran, sodium oxybate) have been identified that demonstrate a multidimensional efficacy in this condition. Although the complexity of FM suggests that monotherapy, non-pharmacological or pharmacological, will not adequately address the condition, the outcomes from recent clinical trials are providing important clues for treatment guidelines, improved diagnosis, and condition-focused therapies.

Introduction

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a common chronic widespread pain condition in which patients typically present with allodynia and hyperalgesia in addition to experiencing many auxiliary symptoms () (CitationWolfe et al 1990; CitationClauw 1995; CitationJain et al 2003). The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for the classification of FM established in 1990 require a history of widespread pain for at least 3 months and tenderness, determined by a force of 4 kg, in at least 11 of 18 defined tender points (CitationWolfe et al 1990). The presence and severity of FM, which is often reliant on the patient’s self-reported symptoms, cannot be determined by objective clinical findings, radiographic abnormalities or routinely used laboratory tests (CitationMease 2005; CitationArnold 2006). Localized or regional pain in most patients with FM precedes the widespread pain, which could suggest the latter develops from the former. Although pain is often considered the predominant feature, FM is a complex and difficult to treat chronic condition that usually requires a multidisciplinary approach using both pharmacological and non-pharmacological management. Classification and treatment of FM is often further complicated by a waxing and waning course of the symptoms being typical and the presence of co-morbid conditions ().

Table 1 Symptoms of fibromyalgia

Table 2 Examples of conditions frequently co-morbid with fibromyalgia

Many of the symptoms (fatigue, sleep dysfunction, stiffness, depression, anxiety, cognitive disturbance) reported in clinical practice in addition to the pain and tenderness, however, present a condition with a complexity that is probably beyond the ACR 1990 classification (CitationKatz et al 2006). Nevertheless based upon the ACR 1990 criteria, epidemiological studies report prevalence of the condition is 2% to 4% of the general population, increasing to greater than 7% of those over 70 years of age (CitationRooks 2007). The patient population consists of a female to male ratio of 9:1, and the most common age group is 45 to 60 years. Related to this, FM has emerged over the past 20 years as a leading cause of visits to rheumatologists, either alone or as an accompaniment of other rheumatic disorders (CitationBennett et al 2007). Although an epidemiological study looks at the incidence, distribution, and control of a particular disease in a population, the outcomes are dependent on the clarity of definition of the condition. The complexity of FM is probably responsible for limited epidemiological data and thereby a likely underestimation where subjects presenting with FM symptoms remain undiagnosed.

A study published in 2003 examined the general health status and work incapacity, and views on the effectiveness of therapy of patients over a two-year observation period (CitationNoller and Sprott 2003). Although there was general satisfaction with quality of life improvement and health status, despite many various treatments received, the patients with FM showed no improvement in pain. The authors suggested that the positive outcomes and satisfaction was probably the result of patient instruction and education of the disease. As a consequence of high prevalence, frequent co-morbidities, and frustration with current treatment modalities, it is increasingly evident that FM represents a significant challenge (CitationHoffman and Dukes 2008).

Further, symptom expression in FM tends to vary on an individual basis, indicative of heterogeneity within the condition and the possibility of subgroups of patients with FM. Several studies have suggested heterogeneity in the presentation of FM with differences in biological variables (eg, positive antinuclear antibodies, cytokine abnormalities, growth hormone, thyroid hormones) supportive of subgroups within the patient population (CitationBennett 1998; CitationAl-Allaf et al 2002; CitationGur et al 2002; CitationSalemi et al 2003; CitationMetyas et al 2007). Subgroups based on responses to pharmacological interventions and psychosocial responses have also been demonstrated (CitationTurk et al 1996; CitationRossy et al 1999; CitationWolfe et al 2000; CitationLawson 2006a; CitationLawson 2008).

Management issues

The management of FM has been complicated by the lack of a universally accepted pathophysiological mechanism and overlap with symptoms of other health conditions (eg, chronic fatigue syndrome, myofascial pain, systemic lupus). The development of focused and mechanistically based therapeutic options targeting the array of symptoms of FM has been limited. Current management approaches of improving health status in FM use a rehabilitation model, rather than a classic biomedical model, integrating exercise, education (stress management programs, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)) and pharmacological treatments (CitationGoldenberg et al 2008). Although recommendations (eg, European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR), American Pain Society (APS)) for FM management have been published (CitationBurckhardt et al 2005; CitationCarville et al 2008), a universally accepted treatment algorhythm or approach is often lacking. A limitation for gaining consensus regarding optimal management of FM is that in the many clinical trials efficacy of the diverse set of treatments has been inconsistent with a large proportion of patients not reporting clinically significant outcomes. The guidelines published by EULAR and APS provide evidence-based considerations related to evaluation and diagnosis of FM, and non-pharmacological and pharmacological therapies (CitationBurckhardt et al 2005; CitationCarville et al 2008). The evidence regarding effectiveness of treatment tended to favor pharmacological studies where double blinding and placebo controls were possible. Management initially is often drug treatment (which may be as a consequence of patient preferences) plus self-management advice to pace activities and follow a regular activity program appropriate to the individual’s need (CitationHammond and Freeman 2006; CitationGoldenberg et al 2008).

There has been a rise in the development of new interventions for the treatment of FM and a variety of outcome measures have been used during clinical trials to assess improvement in patients with FM. Partly due to issues related to the classification of FM there often has not been uniform agreement as to which domains or which assessment tools should be utilized (CitationMease et al 2007). Often assessment of pain is a primary domain of the instrument. FM, however, has an impact on functioning in daily life from the perspective of the patient, although not all pain assessment instruments address these factors. Fatigue in FM is considered by patients to be the second most important domain after pain and may play a role of relative importance in the deterioration of the active state particularly with respect to the long duration of the symptom (CitationMease et al 2007). Thus, the complexity of this condition may limit in clinical practice the potential of a single instrument covering the diversity of symptoms of FM raising difficulties such as insensitivity or efficacy misinterpretation associated with the multidimensionality (CitationProdinger et al 2008).

Treatment options

Evidence supports exercise and education interventions alone and in combination offering benefit for people with FM (CitationBurckhardt et al 2005; CitationBusch et al 2008; CitationCarville et al 2008); however, the content and duration of interventions and outcomes can be unpredictable. Although the number of studies of exercise or behavioral interventions and education has increased in the past decade, comparisons are limited due to a range of factors such as inconsistent outcome measures, assessment tools, small sample size, and high attrition rates (CitationRooks et al 2007). Good outcomes have, however, been reported with a number of forms of relaxation training including electromyography (EMG) biofeedback, heart rate variability (HRV) biofeedback, meditation-based stress reduction, tai-chi, and yoga therapy (CitationDrexler et al 2002; CitationHammond and Freeman 2006; CitationHassett et al 2007; CitationGoldenberg et al 2008). CBT provides improvements in pain-related behavior, coping strategies and overall physical function in patients with FM (CitationTurk et al 1998; CitationNielson and Jensen 2004; CitationBennett and Nelson 2006; CitationThieme et al 2007). Although it has been reported that benefit from CBT can be maintained for 6 months, the efficacy of this form of treatment is often found to be inconsistent and, as a single treatment modality, CBT does not offer distinct advantage over programs of education or exercise (CitationTurk et al 1998; CitationKendall et al 2004; CitationBennett and Nelson 2006). Pretreatment patient characteristics are suggested to be important predictors of the response to CBT and thereby beneficial outcomes (CitationTurk and Flor 1989; CitationThieme et al 2007).

Exercise rehabilitation has recently gained increased acceptance as a component of the symptom management for FM. Modest effects on functional and symptomatic outcomes in patients with FM have been reported with supervised aerobic exercise training such as cycle ergometry, walking, jogging, and water-based activities (CitationJones et al 2006; CitationMaquet et al 2007; CitationBusch et al 2008). These include improvements in measures of cardiovascular fitness, Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) subcales of wellbeing and sleep, psychological function, pain-pressure threshold, and participant-rated and physician-rated disease severity (CitationMannerkorpi, 2005; CitationJones et al 2006; CitationMaquet et al 2007; CitationBusch et al 2008). The ability to engage in long, continuous bouts of activity is often limited by the pain associated with FM, therefore alternative systems, such as interval-type training are likely to be more appealing and tolerable for this patient group. In addition, exercises and activities that strengthen the skeletal muscles (eg, stretching) that do not cause undue pain are also important for patients with FM (CitationJones et al 2002; CitationOkumus et al 2006; CitationMatsutani et al 2007; CitationBircan et al 2008; CitationBusch et al 2008).

Pharmacological therapies

The pharmacological approach to the management of the condition has often been influenced by the debate of whether FM is a single entity or a collection of symptoms. As a consequence, drug therapy has often focused toward the individual symptoms, particularly pain, with current pharmacological treatments () remaining largely empiric (CitationLawson 2006a; CitationLawson 2008). The failure of anti-inflammatory medications, such as the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, naproxen and ibuprofen, and prednisone to be effective treatments of FM supports a lack of underlying peripheral structural damage and inflammatory signs (CitationClark et al 1985; CitationGoldenberg et al 1986; CitationYanus et al 1989). A sensory abnormality, with alterations in substance P levels, N-methyl-D-aspartate acid (NMDA) receptors and mono-aminergic activity within the central nervous system (CNS) of patients with FM that would be comparable with central sensitization of nociceptive afferent pathways creating a stimulus-independent pain state has been proposed (CitationDesmeules et al 2003; CitationAbeles et al 2007; CitationMartinez-Lavin 2007). Clinical trials of opioid agonists as treatments of FM have been limited and often ineffective. The usefulness of opioids in controlling FM pain may be hindered by the suggestion that the opioid systems are maximally activated or a decreased availability of central μ-opioid receptors results in a reduced efficacy in this patient group (CitationBaraniuk et al 2004; CitationHarris et al 2007).

Table 3 Examples of current pharmacological treatments of fibromyalgia

Recent studies have emphasized the global state of the patient as being an important consideration with quality of life outcomes evaluation as an efficacy assessment of pharmacological therapies. This has identified the value of a number of pharmacological targets in the management of FM, in addition to offering insights to aspects of the pathophysiology of the condition.

Bioamine modulators

There appears to be a failure in patients with FM to modulate pain due to noxious stimuli because of dysfunction in the descending inhibitory pain pathways (CitationKosek and Hansson 1997; CitationStaud et al 2003; CitationJulien et al 2005). Serotonergic and norepinergic neurons in the descending inhibitory system that links the periaqueductal gray and the rostal ventromedial medulla with the spinal cord are involved in pain regulation (CitationAbeles et al 2007). Thus, enhancement of the activity of serotonin and norepinephrine within these structures would be expected to evoke analgesia.

Often antidepressants, particularly tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) such as amitriptyline and dothiepin, have been first-line pharmacological therapies for FM (CitationArnold 2006; CitationLawson 2006a). Low-dose TCAs have been significantly effective in the management of sleep, pain, and fatigue in patients with FM (CitationCarette et al 1994; CitationCarette et al 1995; CitationRicheimer et al 1997; CitationRao and Clauw 2004; CitationBaker and Barkhuizen 2005; CitationMease 2005; CitationGoldenberg 2007). Inhibition of the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine into the neuronal terminals of the descending tracts by low-dose TCAs has been suggested to be responsible for analgesic effect of these agents in FM. Although clinically applicable improvement in pain (≥30% reduction) with TCAs was observed in randomized controlled trials (RCTs), this was often limited to 25% to 45% of FM patients given these drugs (CitationCarette et al 1994, Citation1995; CitationRicheimer et al 1997). The limited utility of TCAs as treatments of FM has been related to unpredictable responses, adverse effects, and a lack of long-term efficacy evidence.

The evaluation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in clinical trials with FM patients have shown mixed results (CitationWolfe et al 1994; CitationAnderberg et al 2000; CitationArnold et al 2002; CitationPatkar et al 2007). Agents with mixed serotonin and norepinephrine activity (eg, fluoxetine and paroxetine) have demonstrated greater efficacy in the management of FM than SSRIs with higher specificity for serotonin reuptake inhibition (eg, citalopram). The conclusion that agents with higher selective activity are less consistent as treatments of FM is supported by the finding that the combination of fluoxetine and amitriptyline was more effective (reduced pain and FIQ scores, and improved sleep) than either drug alone (CitationGoldenberg et al 1996).

New serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs; eg, duloxetine, milnacipran, venlafaxine) have become the focus of recent RCTs (CitationArnold 2006; CitationLawson 2006a). Duloxetine has a balanced inhibitory profile of serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake, while milnacipran, similarly to amitriptyline, preferentially inhibits norepinephrine reuptake, but also exhibits weak NMDA receptor inhibition (CitationShuto et al 1995; CitationStahl et al 2005). Duloxetine significantly improved measures of pain and several measures of quality of life (eg, FIQ, Clinical Global Impressions (CGI), Patient Global Impression (PGI)) in patients with FM, with and without depression (CitationArnold et al 2004, Citation2005). The reduction of pain and improved quality of life by duloxetine were independent of the presence of depression suggesting the symptoms of FM are not related to this mood state. Although duloxetine is an effective treatment of FM, this has predominantly been observed in female patients and a 50% decrease or greater in any pain score was only achieved in up to 41% (dependent on the treatment regime) of subjects (CitationArnold et al 2004, Citation2005). During 6 months of treatment, duloxetine demonstrated durability with outcomes superior to placebo in the improvement of pain and secondary measures such as FIQ, CGI, and Short Form 36 (SF-36) scores (CitationRussell et al 2008). Although fatigue is a common symptom reported by patients with FM (CitationMease et al 2007), duloxetine failed to improve general or physical fatigue during the course of the trial. Interestingly though, a significant improvement was obtained in the mental fatigue domain suggesting that duloxetine treatment could improve the cognitive dysfunction associated with FM (CitationRussell et al 2008).

Milnacipran relieves pain symptoms and improves measures of quality of life (eg, PGI and FIQ scores) associated with FM (CitationVitton et al 2004; CitationGendreau et al 2005). A reduction of pain by 50% or greater was observed in up to 37% of the patient population and a greater improvement in pain reduction was recorded in non-depressed subjects treated with milnacipran. These findings are consistent with the analgesic effects of milnacipran, like those of duloxetine, not being as a consequence of improvement of mood. The durable efficacy of milnacipran as a treatment of FM has been demonstrated in 15-week, 6-month, and 12-month RCTs where multidimensional symptom improvement was reported (CitationClauw et al 2007a, Citationb; CitationGoldenberg et al 2007).

The SNRIs, duloxetine and milnacipran, are well tolerated because they do not interact with adrenergic, cholinergic, or histaminergic receptors, or sodium channels and thereby lack many of the adverse effects of TCAs. It is of note, however, that insomnia was a frequently reported adverse effect for duloxetine in a condition that presents sleep dysfunction as a major symptom (CitationArnold et al 2004, Citation2005; CitationRussell et al 2008).

Therefore, agents that modulate serotonin and norepinephrine are effective treatments for some, but not all, patients with FM. Although SNRIs are well tolerated, the observation that a significant number of patients do not gain benefit from this treatment can question the relationship of this mechanism of action and the pathophysiology of FM. A critical issue that could be addressed by other SNRIs would be the balance of the norepinephrine versus serotonin reuptake inhibition. Although modulation of serotonin and norepinephrine levels is the primary mechanism of TCAs, SSRIs, and SNRIs, these agents act on multiple nociceptive targets (eg, NMDA receptors, potassium channels) at central and peripheral locations, the contribution of which to the clinical outcomes obtained is unknown (CitationLawson 2002; CitationMico et al 2006). The NMDA receptor antagonists ketamine and dextromethorphan have demonstrated efficacy (pain score) as analgesics in the treatment of FM (CitationClark and Bennett 2000; CitationGraven-Nielsen et al 2000; CitationCohen et al 2006). Due to a lack of specificity and thereby associated adverse effects, however, NMDA receptor antagonists are not widely accepted as treatments of chronic pain. Interestingly potassium channels, whose functional state has been studied in patients with fibromyalgia, are molecular targets for the management of pain (CitationLawson 2006b; CitationLawson et al 2008). These molecules have been developed to act optimally at sites related to the bioamine systems and not at the auxillary targets, which could account for the lack of universal effectiveness in this patient population.

It is interesting to note that a reduction in pain and an improvement in health-related quality of life in patients with FM have been demonstrated with tramadol alone, or in combination with acetaminophen (CitationBennett et al 2005). The pharmacological properties of tramadol, which is included in both the EULAR and APS guidelines for FM management, are a mixture of serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibition and weak μ-opioid receptor agonism (CitationFrink et al 1996). The contribution of each of these mechanisms to the outcomes obtained with tramadol is unknown.

In addition to norepinephrine and serotonin, dopamine plays a role in the descending inhibitory pain pathways at the supraspinal level of the thalamus, basal ganglia, and limbic cortex (CitationShyu et al 1992; CitationChudler and Dong 1995; CitationBurkey et al 1999; CitationLopez-Avila et al 2004). An abnormal dopamine response to pain in patients with FM, which may be related to prolonged stress, has been reported (CitationWood et al 2007a). A disruption of dopaminergic neurotransmission being involved in the pathophysiology of FM has been further proposed due to a reduction of presynaptic dopamine metabolism, demonstrated by positron emission tomography, in these patients (CitationWood et al 2007b). In one RCT, the dopamine D3/D2 receptor agonist pramipexole reduced pain and improved fatigue and overall function as indicated by the FIQ score in patients with FM with no withdrawals from the study because of adverse effects (CitationHolman and Myers 2005). However, as observed with other pharmacological treatments, pramipexole failed to evoke 50% or greater decrease in pain in all patients involved in the clinical trial with this efficacy level only being achieved in 42% of subjects. The patients in this trial, however, were taking their current medication, which included opioid analgesics, making the study outcomes difficult to interpret. Ropinirole, another dopamine D3/D2 receptor agonist, failed to achieve a significant therapeutic response in patients with FM (CitationHolman 2004); whether the lack of efficacy of ropinirole is independent of dopamine receptor modulation remains to be established.

Alpha2-delta ligands

The release of neurotransmitters that play a role in pain processing, such as glutamate and substance P, is regulated by calcium influx into nerve terminals within the nociceptive pathways (CitationMillan 2002; CitationDooley et al 2007). Block of the presynaptic calcium channels by ligands of the α2δ subunit of that channel (eg, gabapentin, pregabalin) will decrease the neurotransmitter release and attenuate abnormal hyperexcitability of neuronal networks such as that associated with chronic pain. Functionally, α2δ-subunit ligands exhibit use-dependent properties giving these drugs a significant clinical advantage in that they will be expected to significantly modulate pathological functions related to maintained depolarization or hyperexcitability, but only minimally alter physiological synaptic function (CitationDooley et al 2007).

In patients with FM, gabapentin improved pain, FIQ, CGI, and PGI scores and sleep quality, however with a high incidence of adverse effects (eg, sedation, dizziness) (CitationArnold et al 2007a). Although a 30% or greater reduction in pain score was only achieved in 51% of gabapentin-treated patients, these findings support this concept as a therapeutic approach to FM. Pregabalin significantly reduced the pain score and improved sleep and fatigue in RCTs (of 8, 13, and 14 weeks) involving patients with FM, demonstrating efficacy against the three major symptoms of the condition (CitationCrofford et al 2005; CitationArnold et al 2007b; CitationMease et al 2008). Although pregabalin monotherapy provides benefit in the management of FM as demonstrated by significantly more patients gaining 50% or greater improvement in pain with drug treatment than placebo treatment, this level of benefit was in a limited (up to 30%) number of subjects. The number of pregabalin responders only increased up to 50% of the subjects when an efficacy level of 30% or greater decrease in pain scores was determined. Further, little additional benefit, with an increase in the incidence of adverse effects, was conferred by the highest dose (600 mg/day) of pregabalin studied relative to that gained with the lower doses (300 and 450 mg/day) suggesting that in pregabalin-responders an efficacy ceiling was met (CitationCrofford et al 2005; CitationArnold et al 2007b; CitationMease et al 2008).

The durability of the effects of pregabalin on pain, fatigue, and sleep disturbance was demonstrated in a 6-month, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, with an onset of beneficial effects within 1 week of treatment (CitationCrofford et al 2008). The durability of the treatment was determined by the time to loss of therapeutic response in patients who had previously demonstrated improvement in FM symptoms with pregabalin. At the end of the trial, 68% of drug-treated patients compared to 39% of placebo-treated patients maintained therapeutic response related to improvement in pain, sleep, fatigue, and functional status. Although more pregabalin- than placebo-treated patients discontinued due to adverse effects, pregabalin was well tolerated (CitationCrofford et al 2008). Pregabalin has recently been approved by the FDA for the treatment of FM.

Hypnotics

Sedative hypnotics that modulate benzodiazepine receptors receptor complex (BZD1 and BZD2) located on the GABAA have been evaluated in patients with FM (CitationArnold 2006; CitationLawson 2006a; CitationRooks 2007). The benzodiazepines, temazepam, alprazolam, and bromazepam, which act non-selectively at BZD receptors, have given inconsistent results in clinical trials in patients with FM. Although temazepam improved sleep quality, no concomitant improvement in pain or fatigue symptoms was observed (CitationHench et al 1989). Thus, a symptomatic benefit outcome was evoked by modulation of BZD receptors by benzodiazepines rather than management of the condition. Although benzodiazepines are useful in conditions involving neuronal hyperexcitability (eg, epilepsy, spasticity) and would be assumed to have the potential of controlling the pain related to the enhanced general sensitization in FM, acceptable efficacy has not been observed. Zolpidem and zopiclone, short-acting non-benzodiazepine hypnotics which interact preferentially with the BZD1 receptor, also improved sleep in patients with FM, but again failed to improve pain (CitationDrewes et al 1991; CitationGrönblad et al 1993; CitationMoldofsky et al 1996). The failure of modulators of processes within the GABAergic inhibitory neurons to provide suppression of the symptoms of FM could suggest that the pathophysiology does not involve a state of hyperexcitability, but is related to an altered threshold of neuronal activation.

Sodium oxybate, the sodium salt of gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB), provided significant improvements in the major symptoms of FM (ie, pain, tenderness, sleep quality, and fatigue), which have been largely attributed to its capacity to consolidate and improve deep sleep (CitationRussell et al 2005; CitationWood 2006). The improvement in pain, at least, being related to improved sleep is supported by the outcome of a significant correlation (r = 0.55, p < 0.001) between changes in the pain scale and improvements in sleep quality. The specific processes responsible for the sleep disruption in FM are unclear. Sleep impacts on pain, fatigue, and social functioning (CitationSchaefer 2003; CitationTheadom et al 2007); nevertheless, it is not clear whether sleep disturbance is a symptom occurring itself or as a co-morbidity. It has been suggested that the relationship between pain and sleep may be bidirectional such that pain might increase sleep disturbance and disturbed sleep could intensify pain (CitationAffleck et al 1996). Whether the pathophysiology for one symptom is responsible for the initiation of another symptom, or a single mechanism is concomitantly responsible for more than one symptom still requires determination. GHB is a precursor to GABA and exhibits agonist receptor and a postulated GHB-specific activity at the GABAB receptor (CitationMaitre 1997). Data are awaited as to which, if any, is the primary mechanism responsible for the effectiveness and thereby beneficial outcomes with sodium oxybate in the management of FM (CitationMitler and Hayduk 2002).

Pathophysiology

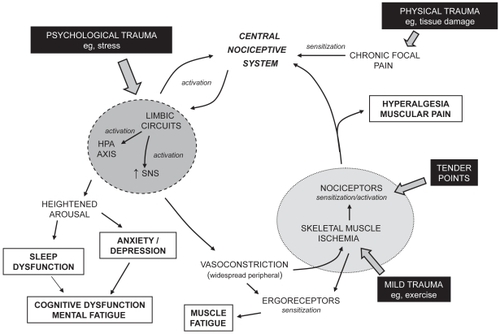

A number of hypotheses have been proposed regarding the pathophysiology of FM, which includes a dysfunction of pain modulatory systems within the CNS, neuroendocrine dysfunction, and dysautonomia (CitationSarzi-Puttini et al 2006; CitationAbeles et al 2007; CitationArendt Neilsen and Henriksson 2007; CitationTanriverdi et al 2007). FM is often described as a condition of heightened generalized sensitization to sensory input presenting as a complex of symptoms including pain, although lacking signs of underlying peripheral structural damage and inflammation. A cyclic model of the potential interrelationship of the proposed pathophysiological processes and the primary symptoms associated with FM is presented in . Altered processing within the central nociceptive system is often proposed to be central to the manifestation of the condition and the typically experienced symptoms. As a consequence, pain has been described as both a symptom and a contributor of other symptoms such as fatigue, impairment of concentration, negative mood, degraded sleep, and diminished overall activity (Tuck and Dworkin 2004). Nevertheless, the nociceptive system is possibly one component of a complex network of physiological aspects that express a level of interdependence creating the clinical profile of FM. The cause of the interference in pain processing remains unclear, although involvement of chronic psychological stressors, peripheral pain generators, and inflammatory mediators has been proposed (CitationBennett 2005; CitationAbeles et al 2007).

Figure 1 A cyclic model of the pathophysiological processes associated with fibromyalgia. Potential triggers of the condition are indicated in filled boxes. Typical symptoms of the condition are indicated in open boxes.

Initiation of altered functioning of the nociceptive system has been related to a physical insult, leading to traumatized tissue and localized pain, or a psychological insult, such as stress () (CitationAaron et al 1997; CitationBuskila et al 1997; CitationAl-Allaf et al 2002;Tishler et al 2006). Sensitization of the central nociceptive system occurs due to such a sensory input. Central sensitization implies spontaneous nerve activity, expanded receptive fields, and abnormal temporal summation (or ‘wind-up’) within the spinal cord. NMDA receptors, found at the postsynaptic membrane in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, are proposed to play a role in these phenomena. Once central (sensitization) hyperexcitability has been established, subsequent responses to normal stimuli are exaggerated and the threshold for the activation of new inputs is reduced. Central to a variety of neuronal processes, including synaptic plasticity and neurotoxicity, is the activation of NMDA receptors by glutamate leading to a rise in intracellular calcium and the initiation of second messenger pathways that mediate long-term potentiation (enduring enhancement of synaptic transmission after the initiating stimulus has ceased) (CitationMacDermott et al 1986; CitationThomas 1995; CitationRessler et al 2002). In addition, nitric oxide production by neuronal nitric oxide synthase is induced by the calcium influx, which is believed to evoke a retrograde signaling action enhancing presynaptic glutamate release (CitationDeMaria et al 2007). Studies on levels of nitric oxide in FM, however, have not been conclusive (CitationOzgocmen et al 2006). Similarly substance P, a peptide neurotransmitter associated with pain transmission, in addition to many other actions enhances the responsiveness of NMDA receptors to glutamate (CitationDeMaria et al 2007). Although elevated levels of substance P in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with FM have been reported (CitationVaerøy et al 1988; CitationRussell et al 1994), such observations have not been confirmed in other studies. In patients with fibromyalgia temporal summation of nociceptive stimuli (where the intensity of rapidly repeated noxious stimuli is perceived to increase) is enhanced and diffuse noxious inhibitory control is reduced (CitationLautenbacher and Rollman 1997; CitationStaud et al 2003; CitationJulien et al 2005).

Studies utilizing neuroimaging techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) have demonstrated that patients with FM exhibit neural activity in regions involved in processing the sensory pain sensation, in response to the administration of a noxious pressure or heat stimulus, that differs from that observed in health controls (CitationWilliams and Gracely 2006; CitationGuedj et al 2007a). Although both patients with FM and healthy controls detect and experience a full range of perceived pain stimuli, the stimulus intensity threshold of the former group is significantly lower. The status of neural activity in the patients with FM was related to physiological and not psychological stimuli as mood states, such as depression, did not appear to influence the outcome. Data from SPECT neuroimaging studies have also been predictive of therapeutic responsiveness of treatment of patients with FM with amitriptyline and ketamine (CitationAdiguzel et al 2004; CitationGuedj et al 2007b). It is important to recognize that such neuroimaging techniques do not measure neural activity directly, but infer activity from localized changes in regional cerebral blood flow occurring in response to neural metabolic demand. Further work is required to determine whether these observations are related to neural demand influencing vascular status or whether a compromised vasculature, due to dysautonomia, is impacting on neural activity, or a combination of both. Neuroimaging has focused on the pain dimension of FM, where other symptoms such as fatigue and disturbed sleep have a significant role, as do non-noxious stimuli such as auditory and tactile (CitationGeisser et al 2008).

The intensity and duration of the insult, and thereby pain, required to achieve the level of sensitization related to FM is not understood. Data from genetic studies could indicate a familial predisposition in vulnerable subjects to the development of FM (CitationBuskila and Sarzi-Puttini 2006). Although the frequency of polymorphisms of the serotonin transporter promoter gene, 5-HT2A receptor gene, catechol-O-methyltransferase gene, and dopamine D4 receptor gene is changed in patients with FM, the relevance to the etiology and pathophysiology is unknown (CitationBondy et al 1999; CitationOffenbaecher et al 1999; CitationCohen et al 2002; CitationGursoy et al 2003; CitationBuskila et al 2004). Consequently what would be an innocuous event in the majority of the people has a marked outcome in 2%–4% of the population.

In addition to increasing the sensitivity of the central nociceptive system the sensory inputs appear to lead to activation of circuits of the limbic system such as the autonomic nervous system and the neuroendocrine hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis (). HPA axis dysfunction in patients with FM is characterized by elevated cortisol levels lacking diurnal fluctuation with blunted secretion in response to stress (CitationAbeles et al 2007; CitationTanriverdi et al 2007). This is consistent with the HPA axis being underactivated to stimuli and some patients with FM exhibiting a subnormal adrenocortical function. There are no structural abnormalities in the endocrine glands of the HPA axis and current data do not allow an explanation of the location of the defect of the HPA dysfunction. Dysautonomia has also been suggested to be responsible for the generation and maintenance of the symptoms of FM (CitationMartinez-Lavin 2007). Selective sympathetic blockade with guanethidine in patients with FM leads to a reduction in pain and number of tender points with restoration of the symptoms by norepinephrine injections (CitationBackman et al 1988; CitationMartinez-Lavin 2004). An increased sympathetic and decreased parasympathetic activity in patients with FM resulting in a persistently hyperactive sympathetic nervous system that is hyporeactive in response to stress has been reported (CitationMartinez-Lavin et al 1997; CitationMartinez-Lavin et al 1998; CitationCohen et al 2000). Chronic hyperstimulation of the α-adrenergic receptors of the sympathetic nervous system could lead to receptor desensitization and downregulation. The augmented sympathetic activity appears to be greater in women than men, suggesting that women with FM may have more severe autonomic dysfunction. Although TCAs and SNRIs, through modulation of bioamine levels, may achieve benefit in the treatment of FM by an effect on descending pain pathways, the lack of tolerance or efficacy of these drugs may be associated with an augmentation of the sympathetic component of the dysautonomia.

FM patients demonstrate significant variability in stress reactivity and the different response patterns related to potential autonomic response specificity (CitationTurk and Flor 1989; CitationThieme et al 2006). The activation of the processes related to the limbic circuits in patients with FM appears to express an increased sensitivity to stressors perhaps due to the altered functioning preventing a normal physiological regulation of such an event and thereby exacerbation of certain systems. For example the limbic system, HPA axis, and autonomic nervous system activation could be related to mood arousal resulting in altered sleep architecture and enhanced anxiety leading to depression. Such outcomes within the limbic system may also be related to the memory and cognitive function, and mental fatigue (fibrofog) in patients with FM (CitationGoldenberg et al 2008). The blunted sympathetic activity to stress and impaired parasympathetic modulation of the dysautonomia may also be associated with the prevalence of symptoms such as syncope, morning stiffness, pseudo-Raynaud’s phenomenon, and intestinal irritability observed in this patient population (CitationSarzi-Puttini et al 2006; CitationMartinez-Lavin 2007).

Stress has central hyperalgesic effects that could be due to a direct central nociceptive system or an indirect peripheral action. The enhanced peripheral sympathetic nervous system tone related to the dysautonomia will, for example, lead to generalized widespread peripheral vasoconstriction (in addition to other autonomic responses). As a consequence of an associated reduced blood flow, a relatively mild challenge (eg, stretching, light exercise) to the skeletal muscle can evoke a state of ischemia and changed muscle energy metabolism. Low levels of phosphocreatine and ATP at rest, low phosphorylation potential, and total oxidative capacity, and a reduced number and size of mitochondria in skeletal muscle of patients with FM have been identified (CitationBengtsson et al 1986; CitationBartels and Danneskiold-Samsøe 1988; CitationJubrias et al 1994; CitationMcIver et al 2006). Such a vascular event would cause the sensitization of ergoreceptors, with the potential outcome of muscle fatigue, and the sensitization or activation of nociceptors leading to multifocal muscular pain and hyperalgesia well beyond the area of the initial physical insult. The generalized sensitization to pain within skeletal muscle will be associated with spatially distributed allodynia and hyperalgesia (tender points). Therefore, changes in peripheral factors, especially in intramuscular microcirculation and in muscle energy metabolism, could act as excitatory triggers for the alterations in the nociceptive system in the CNS and for multifocal pain in the muscles (CitationHenriksson 1999; CitationAbeles et al 2007). The activation of the nociceptors leading to further activation of the central nociceptive system will complete a loop within the processes related to the pathophysiological mechanisms of FM ().

The potential of development of cyclic processes enables a trigger (eg, tender points, tissue trauma, exercise, stress) at any point within the loop to initiate and express (to varying degrees) the array of symptoms typical of FM. Evidence suggests patients with FM exhibit greater sensitivity to a range of sensory stimuli including auditory, tactile, heat, and pressure (CitationGeisser et al 2003; CitationCarrillo-de-la-Pena et al 2006; CitationMontoya et al 2006; CitationGeisser et al 2008). The heightened responsiveness to sensory stimulation may be related to a lack of inhibitory control over repetitive or irrelevant somatosensory stimulation (CitationGeisser et al 2003; CitationCarrillo-de-la-Pena et al 2006; CitationMontoya et al 2006; CitationGeisser et al 2008). These findings are consistent with FM being in part due to a global disturbance in sensory processing rather than an isolated abnormality in pain processing.

Conclusion

FM is a common, complex, and difficult to treat chronic widespread pain disorder, which usually requires a multidisciplinary approach using both pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions. It is described as a condition of heightened generalized sensitization to sensory input presenting as a complex of symptoms including pain, where the pathophysiology could include dysfunction of the CNS pain modulatory systems, dysfunction of the neuroendocrine system, and dysautonomia. Current data do not allow an understanding of the exact locations of the defects in these systems. In addition, whether aspects of the proposed pathophysiology are causal or consequential requires clarification. A cyclic model of the pathophysiological processes is compatible with the interrelationship of primary symptoms and the array of postulated triggers associated with FM.

Although a variety of treatment modalities have been utilized in the management of FM, an effective (>50% of the patient population gaining benefit) means of therapy is still awaited. Treatments have demonstrated an improvement in health status in a proportion of patients with FM in clinical trials; however, these findings require confirmation in usual-care settings of the subjects. Many of the molecular targets of current and emerging drugs used to treat FM have been focused to the management of discrete symptoms rather than the condition. Drugs (eg, pregabalin, duloxetine, milnacipran, sodium oxybate) have now been identified that demonstrate a multidimensional efficacy in this condition. The large percentage of patients who are refractory to these treatments during RCTs, makes it difficult to determine the relationship of the primary mechanism of action of the drugs to the pathophysiology of FM. Although the complexity of FM suggests that monotherapy, non-pharmacological or pharmacological, will not adequately address the condition, the outcomes from recent clinical trials are providing important clues for treatment guidelines, improved diagnosis, and condition-focused therapies. Finally, the diversity of the biology related to FM and the variability in responsiveness to treatments is consistent with the existence of subgroups of patients with potentially differing pathophysiology.

Disclosures

The author has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- AaronLABradleyLAAlarconGS1997Perceived physical and emotional trauma as precipitating events in fibromyalgia: association with health care seeking and disability status but not pain severityArthritis Rheum40453609082933

- AbelesAMPillingerMHSolitarBM2007Narrative review: the pathophysiology of fibromyalgiaAnn Intern Med146726417502633

- AdiguzelOKaptanogluETurgutB2004The possible effect of clinical recovery on regional cerebral blood flow deficits in fibromyalgia: a prospective study with semiquantitative SPECTSouth Med J97651515301122

- AffleckGUrrowsSTennenH1996Sequential daily relations of sleep, pain intensity, and attention to pain among women with fibromyalgiaPain6836389121825

- Al-AllafAWDunbarKLHallumNS2002A case-control study examining the role of physical trauma in the onset of fibromyalgia syndromeRheumatol414503

- Al-AllafAWOttewellLPullarT2002The prevalence and significance of positive antinuclear antibodies in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome: 2–4 years’ follow-upClin Rheumatol1472712447630

- AnderbergUMMarteinsdottirIvon KnorringL2000Citalopram in patients with fibromyalgia – a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studyEur J Pain4273510833553

- Arendt NeilsenLHenrikssonKG2007Pathophysiological mechanisms in chronic musculoskeletal pain (fibromyalgia): the role of central and peripheral sensitization and pain inhibitionBest Pract Res Clin Rheumatol214658017602994

- ArnoldLMGoldenbergDLStanfordSB2007aGabapentin in the treatment of fibromyalgia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trialArthritis Rheum5613364417393438

- ArnoldLMHudsonEVHudsonJL2002A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, flexible-dose study of fluoxetine in the treatment of women with fibromyalgiaAm J Med112191711893345

- ArnoldLMLuYCroffordLJ2004A double-blind, multicenter trial comparing duloxetine with placebo in the treatment of fibromyalgia patients with or without major depressive disorderArthritis Rheum5029748415457467

- ArnoldLMRosenAPritchettYL2005A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of duloxetine in the treatment of women with FM with or without major depressive disorderPain11951516298061

- ArnoldLMRussellIJDuanE2007bA 14-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, monotherapy trial of pregabalin (BID) in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS)Annual Scientific Meeting of American Academy Neurology www.ampainsoc.org/db2/abstract/view?poster_id=3119#695(accessed 17 May 2008)

- ArnoldLM2006Biology and therapy of fibromyalgia. New therapies in fibromyalgiaArthritis Res Ther821216762044

- BäckmanEBengtssonABengtssonM1988Skeletal muscle functions in primary fibromyalgia: effects of regional sympathetic blockade with guanethidineActa Neurol Scand77187913376744

- BakerKBarkhuizenA2005Pharmacologic treatment of fibromyalgiaCurr Pain Headache Rep9301616157056

- BaraniukJNWhalenGCunninghamJ2004Cerebrospinal fluid levels of opioid peptides in fibromyalgia and chronic low back painBMC Musculoskelet Disord54815588296

- BartelsEMDanneskiold-SamsøeB1988Histological abnormalities in muscle from patients with certain types of fibrositisLancet175572870266

- BengtssonAHenrikssonKGLarssonJ1986Muscle biopsy in primary fibromyalgia. Light-microscopical and histochemical findingsScand J Rheumatol15162421398

- BennettRNelsonD2006Cognitive behavioral therapy for fibromyalgiaNat Clin Pract Rheumatol24162416932733

- BennettR2005Fibromyalgia: present to futureCurr Rheum Rep73716

- BennettRMJonesJTurkDC2007An internet survey of 2,596 people with fibromyalgiaBMC Musculoskelet Disord82717349056

- BennettRMScheinJKosinskiMR2005Impact of fibromyalgia pain on health-related quality of life before and after treatment with tramadol/acetaminophenArthritis Rheum535192716082646

- BennettRM1998Disordered growth hormone secretion in fibromyalgia: a review of recent findings and a hypothesized etiologyZ Rheumatol57Suppl 272610025088

- BircanCKaraselSAAkgünB2008Effects of muscle strengthening versus aerobic exercise program in fibromyalgiaRheumatol Int285273217982749

- BondyBSpaethMOffenbaecherM1999The T102C polymorphism of the 5-HT2A-receptor gene in fibromyalgiaNeurobiol Dis6433910527809

- BurckhardtDCGoldenbergDCroffordL2005Guideline for the management of fibromyalgia syndrome pain in adults and childrenAPS Clinical Practice Guidelines Series. No 4Glenview, ILAmerican Pain Society

- BurkeyARCarstensEJasminL1999Dopamine reuptake inhibition in the rostral agranular insular cortex produces antinociceptionJ Neurosci1941697910234044

- BuschAJSchachterCLOverendTJ2008Exercise for fibromyalgia: a systematic reviewJ Rheumatol3511304418464301

- BuskilaDCohenHNeumannL2004An association between fibromyalgia and the dopamine D4 receptor exon III repeat polymorphism and relationship to novelty seeking personality traitsMol Psychiatry9730115052273

- BuskilaDNeumannLVaisbergG1997Increased rates of fibromyalgia following cervical spine injury: a controlled study of 161 cases of traumatic injuryArthritis Rheum40446529082932

- BuskilaDSarzi-PuttiniP2006Biology and therapy of fibromyalgia. Genetic aspects of fibromyalgia syndromeArthritis Res Ther821816887010

- CaretteSBellMJReynoldsWJ1994Comparison of amitriptyline, cyclobenzaprine and placebo in the treatment of fibromyalgiaArthritis Rheum3732408129762

- CaretteSOaksonGGuimontC1995Sleep electroencephalography and the clinical-response to amitriptyline in patients with fibromyalgiaArthritis Rheum38121177575714

- Carrillo-de-la-PeñaMTValletMPérezMI2006Intensity dependence of auditory-evoked cortical potentials in fibromyalgia patients: a test of the generalized hypervigilance hypothesisJ Pain7480716814687

- CarvilleSFArendt-NielsenSBliddalH2008EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia syndromeAnn Rheum Dis675364117644548

- ChudlerEHDongWK1995The role of the basal ganglia in nociception and painPain603387715939

- ClarkSTindallEBennettRM1985A double blind crossover trial of prednisone versus placebo in the treatment of fibrositisJ Rheumatol1298033910836

- ClarkSRBennettR2000Supplemental dextromethorphan in the treatment of FM. A double blind, placebo controlled study of efficacy and side effectsArthritis Rheum43S333

- ClauwDJPalmerRHThackerK2007aMilnacipran efficacy in the treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome: a 15-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialProgram and abstracts of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 71st Annual MeetingNovember 6–11, 2007Boston, MA [Abstract #L1]

- ClauwDJPalmerRHVittonO2007bThe efficacy and safety of milnacipran in the treatment of fibromyalgiaProgram and abstracts of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 71st Annual MeetingNovember 6–11, 2007Boston, MA [Abstract #716]

- ClauwDJ1995Fibromyalgia: more than just a musculoskeletal diseaseAm Fam Physician528534

- CohenHBuskilaDNeumannL2002Confirmation of an association between fibromyalgia and serotonin transporter promoter region (5-HTTLPR) polymorphism, and relationship to anxiety-related personality traitsArthritis Rheum46845711920428

- CohenHNeumannLShoreM2000Autonomic dysfunction in patients with fibromyalgia: application of power spectral analysis of heart rate variabilitySemin Arthritis Rheum292172710707990

- CohenSPVerdolinMHChangAS2006The intravenous ketamine test predicts subsequent response to an oral dextromethorphan treatment regimen in fibromyalgia patientsJ Pain7391816750795

- CroffordLJMeasePJSimpsonSL2008Fibromyalgia relapse evaluation and efficacy for durability of meaningful relief (FREEDOM): a 6-month double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with pregabalinPain1364193118400400

- CroffordLJRowbothamMCMeasePJ2005Pregabalin for the treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome. Results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialArthritis Rheum5212647315818684

- DeMariaSHassettALSigalLH2007N-Methyl-D-aspartate receptor-mediated chronic pain: new approaches to fibromyalgia syndrome etiology and therapyJ Musculoskeletal Pain153344

- DesmeulesJACedraschiCRapitiE2003Neurophysiologic evidence for a central sensitization in patients with fibromyalgiaArthritis Rheum481420912746916

- DooleyDJTaylorCPDonevanS2007Ca2+ channel alpha2delta ligands: novel modulators of neurotransmissionTrends Pharmacol Sci28758217222465

- DrewesAMAndreasenAJennumP1991Zopiclone in the treatment of sleep abnormalities in fibromyalgiaScand J Rheumatol20288931925417

- DrexlerARMurEJGüntherVC2002Efficacy of an EMG-biofeedback therapy in fibromyalgia patients. A comparative study of patients with and without abnormality in (MMPI) psychological scalesClin Exp Rheumatol206778212412199

- FrinkMCHenniesHHEnglbergerW1996Influence of tramadol on neurotransmitter systems of the rat brainArzneimittelforschung461029368955860

- GeisserMECaseyKLBruckschCB2003Perception of noxious and innocuous heat stimulation among healthy women and women with fibromyalgia: association with mood, somatic focus, and catastrophizingPain1022435012670665

- GeisserMEGlassJMRajcevskaLD2008A psychophysical study of auditory and pressure sensitivity in patients with fibromyalgia and healthy controlsJ Pain94172218280211

- GendreauRMThomMDGendreauJF2005Efficacy of milnacipran in patients with fibromyalgiaJ Rheumatol3219758516206355

- GoldenbergDLBradleyLAArnoldLM2008Understanding fibromyalgia and its related disordersPrim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry101334418458727

- GoldenbergDLClauwDJPalmerRH2007One-year durability of response to milnacipran treatment for fibromyalgiaProgram and abstracts of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 71st Annual MeetingNovember 6–11, 2007Boston, MA [Abstract #1526]

- GoldenbergDLFelsonDTDinermanH1986A randomized, controlled trial of amitriptyline and naproxen in the treatment of patients with fibromyalgiaArthritis Rheum29137173535811

- GoldenbergDLMayskiyMMosseyC1996A randomized, double-blind crossover trial of fluoxetine and amitriptyline in the treatment of fibromyalgiaArthritis Rheum39185298912507

- GoldenbergDL2007Pharmacological treatment of fibromyalgia and other chronic musculoskeletal painBest Pract Res Clin Rheum21499511

- Graven-NielsenTAspegren KendallSHenrikssonKG2000Ketamine reduces muscle pain, temporal summation and referred pain in fibromyalgia patientsPain854839110781923

- GrönbladMNykänenJKonttinenY1993Effect of zopiclone of sleep quality, morning stiffness, widespread tenderness and pain and general discomfort in primary fibromyalgia patients. A double-blind randomized trialClin Rheumatol12186918358976

- GuedjECammillenSColavolpeC2007bPredicative value of brain perfusion SPECT for ketamine response in hyperalgesic fibromyalgiaEur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging341274917431615

- GuedjETaiebDCammillenSLussatoD2007a99mTc-ECD brain perfusion SPECT in hyperalgesic fibromyalgiaEur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging34130416933135

- GurAKarakocMNasK2002Cytokines and depression in cases with fibromyalgiaJ Rheumatol293586111838856

- GürsoySErdalEHerkenH2003Significance of catechol-O-methyltransferase gene polymorphism in fibromyalgia syndromeRheumatol Int23104712739038

- HammondAFreemanK2006Community patient education and exercise for people with fibromyalgia: a parallel group randomized controlled trialClin Rehabil208354617008336

- HarrisREClauwDJScottDJ2007Decreased central mu-opioid receptor availability in fibromyalgiaJ Neurosci2710000617855614

- HassettALRadvanskiDCVaschilloEG2007A pilot study of the efficacy of heart rate variability (HRV) biofeedback in patients with fibromyalgiaAppl Psychophysiol Biofeedback3211017219062

- HenchPKCohenRMitlerMM1989Fibromyalgia: effects of amitriptyline, temazepam and placebo on pain and sleep (abstract)Arthritis Rheum32S47

- HenrikssonKG1999Is fibromyalgia a distinct clinical entity? Pain mechanisms in fibromyalgia syndrome. A myologist’s viewBaillieres Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol134556110562376

- HoffmanDLDukesEM2008The health status burden of people with fibromyalgia: a review of studies that assessed health status with the SF-36 or the SF-12Int J Clin Pract621152618039330

- HolmanAJMyersRR2005A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of pramipexole, a dopamine agonist, in patients with fibromyalgia receiving concomitant medicationsArthritis Rheum52249550516052595

- HolmanAJ2004Treatment of fibromyalgia with the dopamine agonist ropinirole: a 14-week double-blind, pilot, randomized controlled trial with 14-week blinded extensionArthritis Rheum50S698

- JainAKCarruthersBMvan de SandeMI2003Fibromyalgia Syndrome: Canadian clinical working case definition, diagnostic and treatment protocols – a consensus documentJ Musculoskeletal Pain113107

- JonesKDAdamsDWinters-StoneK2006A comprehensive review of 46 exercise treatment studies in fibromyalgia (1988–2005)Health Qual Life Outcomes46716999856

- JonesKDBurckhardtCSClarkSR2002A randomized controlled trial of muscle strengthening versus flexibility training in fibromyalgiaJ Rheumatol291041812022321

- JubriasSABennettRMKlugGA1994Increased incidence of a resonance in the phosphodiester region of 31P nuclear magnetic resonance spectra in the skeletal muscle of fibromyalgia patientsArthritis Rheum3780178003051

- JulienNGoffauxPArsenaultP2005Widespread pain in fibromyalgia is related to a deficit of endogenous pain inhibitionPain11429530215733656

- KatzRSWolfeFMichaudK2006Fibromyalgia diagnosis: a comparison of clinical, survey, and American College of Rheumatology criteriaArthritis Rheum541697616385512

- KendallSABartelsEMChristensentR2004A meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioural therapy in fibromyalgiaJ Musculoskelet Pain12Suppl4956

- KosekEHanssonP1997Modulatory influence on somatosensory perception from variation and heterotropic noxious conditioning stimulation (HNCS) in fibromyalgia patients and healthy subjectsPain7041519106808

- LautenbacherSRollmanGB1997Possible deficiencies of pain modulation in fibromyalgiaClin J Pain13189969303250

- LawsonKShawcrossERaphaelJH2008Function of potassium channels in blood mononuclear cells of patients with fibromyalgiaJ Pain Manage1in press

- LawsonK2002Tricyclic antidepressants and fibromyalgia: what is the mechanism of action?Expert Opin Investig Drugs11143745

- LawsonK2006aEmerging pharmacological therapies for fibromyalgiaCurr Opin Invest Drugs76316

- LawsonK2006bPotassium channels as targets for the management of painCNS Agents in Med Chem611928

- LawsonK2008Pharmacological treatments of fibromyalgia: do complex conditions need complex therapies?Drug Discov Today133334018405846

- Lopez-AvilaACoffeenUOrtega-LegaspiJM2004Dopamine and NMDA systems modulate long-term nociception in the rat anterior cingulated cortexPain1111364315327817

- MacDermottABMayerMLWestbrookGL1986NMDA-receptor activation increases cytoplasmic calcium concentration in cultured spinal cord neuronsNature321519223012362

- MaitreM1997The gamma-hydroxybutyrate signalling system in brain: organization and functional implicationsProg Neurobiol51337619089792

- MannerkorpiK2005Exercise in fibromyalgiaCurr Opin Rheumatol17190415711234

- MaquetDDemoulinCCroisierJL2007Benefits of physical training in fibromyalgia and related syndromesAnn Readapt Med Phys50363817467103

- Martinez-LavinMHermosilloAGMendozaC1997Orthostatic sympathetic derangement in subjects with fibromyalgiaJ Rheumatol2471489101507

- Martinez-LavinMHermosilloAGRosasM1998Circadian studies of autonomic nervous balance in patients with fibromyalgia: a heart rate variability analysisArthritis Rheum411966719811051

- Martinez-LavinM2004Fibromyalgia as a sympathetically maintained pain syndromeCurr Pain Headache Rep8385915361323

- Martinez-LavinM2007Biology and therapy of fibromyalgia. Stress, the stress response system, and fibromyalgiaArthritis Res Ther921617626613

- MatsutaniLAMarquesAPFerreiraEA2007Effectiveness of muscle stretching exercises with and without laser therapy at tender points for patients with fibromyalgiaClin Exp Rheumatol25410517631737

- McIverKLEvansCKrausRM2006NO-mediated alterations in skeletal muscle nutritive blood flow and lactate metabolism in fibromyalgiaPain20161916376018

- MeasePArnoldLMBennettR2007Fibromyalgia syndromeJ Rheumatol3414152517552068

- MeaseP2005Fibromyalgia Syndrome: review of clinical presentation, pathogenesis, outcome measures, and treatmentJ Rheum Suppl75621

- MeasePJRussellIJArnoldLM2008A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial of pregabalin in the treatment of patients with fibromyalgiaJ Rheumatol355021418278830

- MetyasSKArkfeldDIbrahimJA2007Inflammatory fibromyalgia: is it real?Ann Rheum Dis66Suppl II625

- MicoJAArdidDBerrocosoE2006Antidepressants and painTrends Pharmacol Sci273485416762426

- MillanMJ2002Descending control of painProg Neurobiol6635547412034378

- MitlerMMHaydukR2002Benefits and risks of pharmacotherapy for narcolepsyDrug Saf2579180912222990

- MoldofskyHLueFAMouslyC1996The effect of zolpidem in patients with fibromyalgia: a dose ranging, double-blind, placebo controlled, modified crossover studyJ Rheumatol23529338832997

- MontoyaPSitgesCGarcía-HerreraM2006Reduced brain habituation to somatosensory stimulation in patients with fibromyalgiaArthritis Rheum541995200316732548

- NielsonWRJensenMP2004Relationship between changes in coping and treatment outcome in patients with Fibromyalgia SyndromePain1092334115157683

- NollerVSprottH2003Prospective epidemiological observations on the course of the disease in fibromyalgia patientsJ Negat Results Biomed2412969513

- OffenbaecherMBondyBde JongeS1999Possible association of fibromyalgia with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene regulatory regionArthritis Rheum422482810555044

- OkumusMGokogluFKocaogluS2006Muscle performance in patients with fibromyalgiaSingapore Med J47752616924355

- OzgocmenSOzyurtHSogutS2006Current concepts in the pathophysiology of FM: the potential role of oxidative stress and nitric oxideRheumatol Int265859716328420

- PatkarAAMasandPSKrulewiczS2007A randomized, controlled, trial of controlled release paroxetine in fibromyalgiaAm J Med1204485417466657

- ProdingerBCiezaAWilliamsDA2008Measuring health in patients with fibromyalgia: content comparison of questionnaires based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and HealthArthritis Rheum59650818438895

- RaoSGClauwDJ2004The management of fibromyalgiaDrugs Today405395415349132

- ResslerKJPaschallGZhouXL2002Regulation of synaptic plasticity genes during consolidation of fear conditioningJ Neurosci22789290212223542

- RicheimerSHBajwaZHKahramanSS1997Utilization patterns of tricyclic antidepressants in a multidisciplinary pain clinic: a surveyClin J Pain1332499430813

- RooksDSGautamSRomelingM2007Group exercise, education, and combination self-management in women with fibromyalgia: a randomized trialArch Intern Med167219220017998491

- RooksDS2007Fibromyalgia treatment updateCurr Opin Rheumatol19111717278924

- RossyLABuckelewSPDorrN1999A meta-analysis of fibromyalgia treatment interventionsAnn Behav Med211809110499139

- RussellIJBennettRMMichalekJE2005Sodium oxybate relieves pain and improves sleep in fibromyalgia syndrome [FM]: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter clinical trialAnnual Meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. AbstL30

- RussellIJMeasePJSmithTR2008Efficacy and safety of duloxetine for treatment of fibromyalgia in patients with or without major depressive disorder: results from a 6-month, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose trialPain1364324418395345

- RussellIJOrrMDLittmanB1994Elevated cerebrospinal fluid levels of substance P in patients with the fibromyalgia syndromeArthritis Rheum3715936017526868

- SalemiSRethageJWolinaU2003Detection of interleukin 1beta (IL-1beta), IL-6 and tumour necrosis factor-alpha in skin in patients with fibromyalgiaJ Rheumatol301465012508404

- Sarzi-PuttiniPAtzeniFDianaA2006Increased neural sympathetic activation in fibromyalgia syndromeAnn N Y Acad Sci10691091716855138

- SchaeferKM2003Sleep disturbances linked to fibromyalgiaHolist Nurs Pract17120712784895

- ShutoSTakadaHMochizukiD1995(+/−)-(Z)-2-(aminomethyl)-1-phenylcyclopropanecarboxamide derivatives as a new prototype of NMDA receptor antagonistsJ Med Chem38296487636857

- ShyuBCKiritsy-RoyJAMorrowTJ1992Neurophysiological, pharmacological and behavioural evidence for medial thalamic mediation of cocaine-induced dopaminergic analgesiaBrain Res572216231611515

- StahlSMGradyMMMoretC2005SNRIs: their pharmacology, clinical efficacy and tolerability in comparison with other classes of antidepressantsCNS Spectrums107324716142213

- StaudRCannonRCMauderliAP2003Temporal summation of pain from mechanical stimulation of muscle tissue in controls and subjects with fibromyalgia syndromePain102879512620600

- TanriverdiFKaracaZUnluhizarciK2007The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia syndromeStress10132517454963

- TheadomACropleyMHumphreyKL2007Exploring the role of sleep and coping in quality of life in fibromyalgiaJ Psychosom Res621455117270572

- ThiemeKRoseUPinkpankT2006Psychophysiological responses in patients with fibromyalgia syndromeJ Psychosom Res61671917084146

- ThiemeKTurkDCFlorH2007Responder criteria for operant and cognitive-behavioral treatment of fibromyalgia syndromeArthritis Rheum57830617530683

- ThomasRJ1995Excitatory amino acids in health and diseaseJ Am Geriatr Soc431279897594165

- TurkDCDworkinRH2004What should be the core outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials?Arthritis Res Ther6151415225358

- TurkDCFlorH1989Primary fibromyalgia is greater than tender points: toward a multiaxial taxonomyJ Rheumatol Suppl198062691687

- TurkDCOkifujiASinclairJD1996Pain, disability, and physical functioning in subgroups of patients with fibromyalgiaJ Rheumatol231255628823701

- TurkDCOkifujiASinclairJD1998Interdisciplinary treatment for fibromyalgia syndrome: clinical and statistical significanceArthritis Care Res11186959782810

- VaerøyHHelleRFørreO1988Elevated cerebrospinal fluid levels of substance P and high incidence of Raynaud phenomenon in patients with fibromyalgia: new features for diagnosisPain322162448729

- VittonOGendreauMGendreauJ2004A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of milnacipran in the treatment of fibromyalgiaHum Psychopharmacol19S27S3515378666

- WilliamsDAGracelyRH2006Biology and therapy of fibromyalgia. Functional magnetic resonance imaging findings in fibromyalgiaArthritis Res Ther822417254318

- WolfeFCatheyMAHawleyDJ1994A double-blind placebo controlled trial of fluoxetine in fibromyalgiaScand J Rheumatol2325597973479

- WolfeFSmytheHAYunusMB1990The American College of Rheumatology (1990) criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia. Report of the multicenter criteria committeeArthritis Rheum33160722306288

- WolfeFZhaoSLaneN2000Preference for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs over acetaminophen by rheumatic disease patients: a survey of 1,799 patients with osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and fibromyalgiaArthritis Rheum433788510693878

- WoodPBPattersonJC2ndSunderlandJJ2007bReduced presynaptic dopamine activity in fibromyalgia syndrome demonstrated with PET: a pilot studyJ Pain851817023218

- WoodPBSchweinhardtPJaegerE2007aFibromyalgia patients show an abnormal dopamine response to painEur J Neurosci2535768217610577

- WoodPB2006A randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multicenter trial comparing the effects of orally administered Xyrem (sodium oxybate) with placebo for the treatment of fibromyalgiaPain Med71812

- YanusMBMasiATAldagJC1989Short term effects of ibuprofen in primary fibromyalgia syndrome: a double blind, placebo controlled trialJ Rheumatol16527322664173