Abstract

Incidence of cardiovascular (CV) and metabolic disease is increasing, in parallel with associated risk factors. These factors, such as low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol, elevated blood pressure, obesity, and insulin resistance have a continuous, progressive impact on total CV risk, with higher levels and numbers of factors translating into greater risk. Evaluation of all known modifiable risk factors, to provide a detailed total CV disease (CVD) and metabolic risk-status profile is therefore necessary to ensure appropriate treatment of each factor within the context of a multifactorial, global approach to prevention of CVD and metabolic disease. Effective and well-tolerated pharmacotherapies are available for the treatment of risk-factors. Realization of the potential health and economic benefits of effective risk factor management requires improved risk factor screening, early and aggressive treatment, improved public health support (ie, education and guidelines), and appropriate therapeutic interventions based on current guidelines and accurate risk assessment. Patient compliance and persistence to available therapies is also necessary for successful modulation of CVD risk.

Introduction

Cardiovascular (CV) disease is the leading cause of disability and death in developed nations and is increasing in prevalence throughout the developing world (CitationWHO 2002). It also poses a huge economic burden; for example, in Sweden in 2005, CV disease (CVD) cost an estimated 48 billion SEK (US$7 billion), as measured in healthcare expenditures, medications, and lost productivity due to disability. The incidence of metabolic disease (including the metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes) is also increasing at an alarming rate in parallel with associated risk factors (CitationFord et al 2004). This has led to an expansion in populations who are at increased risk of developing CVD at an earlier age.

Important advances in CVD and metabolic disease management have been facilitated by the identification of a number of major risk factors, including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, insulin resistance, and obesity. Furthermore, studies determining the interrelated nature of risk factors have helped shape our approach to treatment. However, despite a large clinical evidence base, the implementation of strategies to prevent CVD and metabolic disease remain far from optimal. In this review data are presented underscoring the importance of an intensive global approach to risk management to reduce the clinical and economic burden, profiling the most appropriate therapeutic interventions to achieve this.

Risk factors

Elevated blood pressure (BP), unfavorable levels of LDL and high density (HDL) cholesterol, cigarette smoking, obesity, physical inactivity, and diabetes are well established as major, modifiable CV risk factors (CitationHubert et al 1983). A critically important characteristic of risk factors is that each has a continuous, progressive impact on total CV risk, with higher levels translating into greater risk (CitationGreenland et al 2003). Universal improvements in disease management and public health measures have led to an increasingly aging population in whom these risk factors have more time to cause vascular disease.

CV risk factors occur in clusters

Rather than existing in isolation, CV risk factors tend to occur as clusters (CitationMancia 2006). For example, in a study determining the prevalence of CV disease risk factors among 14,690 Chinese adults aged 35–74 years, overall, 80.5%, 45.9%, and 17.2% of individuals had ≥1, ≥2, and ≥3 modifiable CVD risk factors (from dyslipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, cigarette smoking, or being overweight), respectively. In the US, the figures were 93.1%, 73.0%, and 35.9%, respectively (CitationGu et al 2005). The metabolic syndrome is a particularly well-characterized example of co-existing CV and metabolic risk factors that is increasing in prevalence at an alarming rate (CitationElabbassi and Haddad 2005). Several international organizations have published guidelines for diagnosis of the metabolic syndrome, and differences between guidelines highlight the debate surrounding the precise nature of the metabolic syndrome. In 2006, the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) produced an updated consensus on the definition of the metabolic syndrome which includes central obesity and two additional metabolic criteria ().

Table 1 The new International Diabetes Federation definition for the metabolic syndrome (CitationIDF 2006)

As seen in , metabolic syndrome is a condition, characterized by obesity, in which an individual has a cluster of risk factors that can lead to CVD. The clustering of key risk factors in metabolic syndrome is considered by some to be the result of insulin resistance (CitationDaskalopoulou et al 2004); consequently, the syndrome also carries a greatly increased risk for the development of type 2 diabetes, which in turn increases CV risk even further (CitationZieve 2004). Typically, patients with metabolic syndrome will be older, obese, hypertensive (CitationCsaszar et al 2006), and have insulin resistance (CitationMcLaughlin et al 2003; CitationGrundy 2006). Global estimates of this condition are reported to be around 16% (CitationWild and Byrne 2005); although the situation in the United States is more advanced, where between 30%–40% of the population are reported to have metabolic syndrome (CitationCheung et al 2006; CitationFord 2005).

Clinical relevance of risk factor clustering

The relationship between CV risk factors is synergistic, meaning that when multiple risk factors are present in a specific individual, each one is more important than if they were present in isolation (CitationGreenland et al 2003). Indeed, several studies have shown that a progressively greater number of additional CV risk factors is associated with a correspondingly poorer clinical outcome (CitationStamler et al 1993; CitationThomas et al 2001).

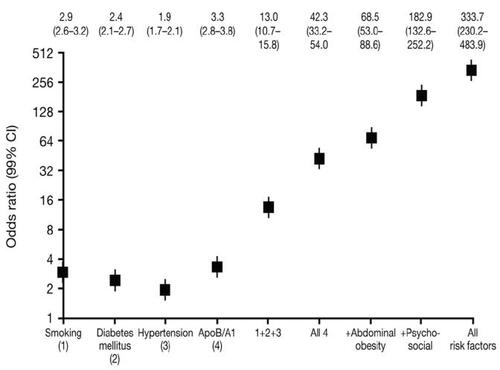

The cumulative effect of modifiable risk factors was well illustrated in the INTERHEART study () (CitationYusuf et al 2004). This standardized case-controlled study of acute myocardial infarction (MI) in 52 countries enrolled 15,152 cases and 14,820 controls. The relationship of smoking, history of hypertension or diabetes, waist:hip ratio, dietary patterns, physical activity, consumption of alcohol, blood apolipoproteins, and psychosocial factors to MI was demonstrated. The odds ratio (OR) for the association of these risk factors to MI and their respective population attributable risk (PAR) were calculated and the nine risk factors studied were reported to collectively represent more than 90% of the risk of an initial MI. In a similar analysis conducted by CitationBaena Diez and colleagues (2002), the association between increasing numbers of CV risk factors and the risk of suffering a major CV event was investigated in a study population of 2,248 patients. The results showed that the percentage of patients with 1, 2, 3, and 4–6 CV risk factors (from smoking, arterial hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, diabetes or obesity) was 32.8%, 17.5%, 6.9%, and 3.7%, respectively. The OR for experiencing a CV event associated to 1, 2, 3, and 4–6 CV risk factors was 1.6 (CI 95%: 0.9–2.7), 2.8 (CI 95%: 1.7–4.7), 3.6 (CI 95%: 1.9–6.5), and 5.6 (CI 95%: 2.9–10.8), respectively, again underlining the escalating risk associated with multiple risk factors.

Figure 1 Cumulative effects of modifiable risk factors in the INTERHEART study – risk of acute MI associated with exposure to multiple risk factors. Copyright © 2004. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier from CitationYusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, et al 2004. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet, 362:937–52.

The mortality associated with the presence of additional CV risk factors in subjects with or without hypertension was analyzed in a study involving >80,000 male subjects (CitationThomas et al 2001). The population was composed of 29,640 normotensive men without additional risk factors (reference group) and 60,343 men with hypertension with and without additional risk factors (familial history of diabetes; total cholesterol ≥250 mg/dL; heart rate >80 beats/min; current smoker; and body mass index [BMI] >28 kg/m2). In patients aged <55 years with hypertension and one or two additional CV risk factors, CV mortality increased five-fold in comparison with normotensive patients. The increased risk was even more apparent in patients who had more than two associated risk factors, where a 15-fold increase in CV risk was observed.

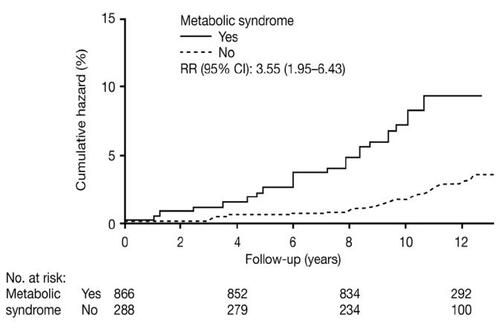

The clinical relevance of risk factor clustering is also well illustrated in patients with the metabolic syndrome. In a study of men aged between 42–60 years, the risk of CVD mortality over approximately 11 years increased at a considerably higher rate when they had metabolic syndrome () (CitationLakka et al 2002). Such patients are at considerable risk of developing atherosclerosis-related diseases, including a two- to four-fold increased risk of stroke and a three- to four-fold increased risk of MI compared with those without the metabolic syndrome (CitationLakka et al 2002; CitationNinomiya et al 2004). The metabolic syndrome also increases the risk of developing diabetes five- to nine-fold (CitationHanson et al 2002; CitationLaaksonen et al 2002).

Figure 2 Relative risk for cardiovascular disease mortality in men (aged 42 and 60 years at baseline) with and without metabolic syndrome. Copyright © 2002 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Reprinted from CitationLakka HM, Laaksonen DE, Lakka TA, et al 2002. The metabolic syndrome and total and cardiovascular disease mortality in middle-aged men. JAMA, 288:2709–16.

Implications for treatment

Screening for risk factors

The synergistic relationship between individual CV risk factors should make the identification and characterization of clusters a healthcare priority. If a patient presents with a particular risk factor, such as elevated BP, they should receive appropriate antihypertensive treatment; however, to establish total risk, a thorough patient assessment should be undertaken. Global risk assessment strategies have a number of benefits (CitationHackam and Anand 2003). A major benefit is that they raise awareness that CV risk is continuous and graded, and that it is related to the overall burden of risk. They also facilitate adjustment to take into account the severity of individual component risk factors. Furthermore, they emphasize that a more individualized treatment approach is required and reiterate that the clinician must not focus on one specific risk factor when multiple CV risk factors are present concomitantly (CitationHackam and Anand 2003). Widely used risk assessment tools include the Framingham risk charts and the Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation (SCORE) risk predicting system. It should be recognized that risk assessment tools should be used with a great amount of clinical judgment and the risk score should never be the only reason for treatment. Many factors that convey an increased risk are not included in the algorithms eg, abdominal obesity, low/high HDL, proteinuria, family history, exercise habits, food habits, and psychosocial factors. An individualized approach is therefore always needed to manage CV risk optimally.

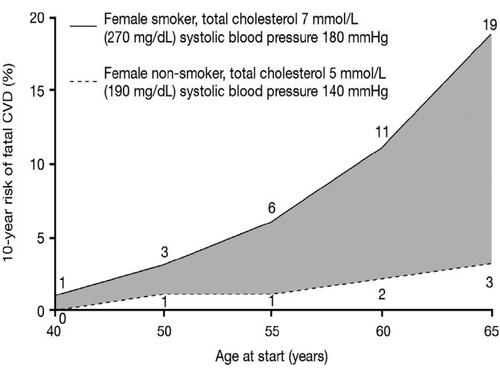

The limitation of all risk scores is also that they only define the CV risk over a limited period of time, usually 10 years. Furthermore, since global risk increases significantly with age they underestimate the risk in young individuals over a life-long perspective. Consequently, in young subjects, even with a clustering of risk factors, the calculated global risk is not high enough to base treatment on a ‘high-risk’ concept. For those at a younger age it is probably easier for both the treating physician and the patient to visualize the risk as the ‘relative risk increase’ rather than the total risk. However, the fact that global risk will escalate with age alone is one that should not be ignored. Clearly, the communication of risk and risk-factor management in younger individuals is still a problem and current algorithms are left distinctly lacking in this respect.

is based on the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) SCORE chart (CitationConroy et al 2003) and shows how age alone changes the 10-year risk if a patient with the same risk profile is seen at different age brackets. It is also clear that young individuals are at lower risk even in the presence of significant risk factors, and there is the potential for lowering risk if treatment is initiated earlier.

Figure 3 Change in risk for cardiovascular disease deaths with increasing age (based on the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) SCORE chart) for a woman in a high-risk population who smokes and has high cholesterol and high blood pressure, compared with a nonsmoker with lower cholesterol and blood pressure values. Data drawn from CitationConroy RM, Pyorala K, Fitzgerald AP, et al 2003. Estimation of ten-year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in Europe: the SCORE project. Eur Heart J, 24:987–1003.

Multifactorial treatment approach to reduce CV events and the development of metabolic disease

Treatment guidelines and society recommendations for the management of CVD and metabolic disease recognize that a multifactorial approach is required. For example, risk scoring and the subsequent implementation of treatment as appropriate is central to the European Society of Hypertension–European Society of Cardiology (ESH–ESC) guidelines, which recommend stratifying patients according to prognosis based on BP levels, lifestyle, target organ damage, and diabetes (ESH–ESC Guidelines Committee 2003). The ESH–ESC guidelines recommend that treatment should address all of these factors and provide BP targets based on overall risk. For example, in patients with diabetes the recommended target BP is lower than that considered acceptable for the general population. Current Joint European Societies Cardiovascular Disease Prevention Guidelines and National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP ATP III) Guidelines also recognize the need for a multifactorial approach and recommend the use of the risk-assessment charts to tailor treatment to each patient’s risk profile (CitationNCEP Expert Panel 2002; CitationDe Backer et al 2003). Similarly, the IDF supports an aggressive, multifaceted treatment approach for individuals with metabolic syndrome (CitationIDF 2006). However, worldwide, physicians still tend to focus on managing a single CV risk factor, for example BP, rather than focusing on overall risk management (CitationVolpe and Tocci 2006). This situation must change if decreases in CV mortality and morbidity, and metabolic disease are to be achieved.

Over recent years, data have emerged to quantify the benefits of a global approach. The Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial (ASCOT) trial showed the benefits of combining antihypertensive and statin therapy (CitationSever et al 2003). The primary objective of each of the two arms of ASCOT (BP lowering arm and lipid-lowering arm [LLA]) was to assess the differential effects on risk of nonfatal MI and fatal coronary heart disease (CHD) of two different treatment strategies assessed in a 2 × 2 factorial design. Following unblinding of the BP treatments in ASCOT-LLA, it was observed that the primary endpoint (nonfatal MI and fatal CHD) was significantly reduced by 53% in the amlodipine/atorvastatin group compared with amlodipine/placebo.

Similarly, in an analysis conducted by CitationAthyros and colleagues (2005), the effect of a multi-targeted treatment approach on CVD risk reduction in nondiabetic patients with metabolic syndrome was assessed. The study was a 12-month, randomized, open-label study, in which 300 nondiabetic patients with the metabolic syndrome and free of CVD at baseline, received lifestyle advice and a stepwise-implemented drug treatment for hypertension, impaired fasting glucose and obesity. The patients were randomly allocated to three treatment groups for hypolipidemic treatment: atorvastatin (n = 100), micronized fenofibrate (n = 100), and both drugs (n = 100). At study end, lipid values were significantly improved in all three treatment groups, with those treated with both atorvastatin and micronized fenofibrate attaining lipid targets to a greater extent than those in the other two groups. The study findings support the concept that a target-driven and intensified intervention aimed at multiple risk factors in nondiabetic patients with the metabolic syndrome substantially offsets its component factors, and significantly reduces the estimated CVD risk (CitationAthyros et al 2005).

Individual risk factor management as part of a global approach

In order to prevent CV and metabolic diseases, each risk factor should be examined and treated appropriately within the context of a multifactorial approach ().

Table 2 Major intervention strategies and recommendations for the management of the individual risk factors associated with cardiovascular and metabolic disease

Lifestyle modification

Guidelines for the management of CV and metabolic disease recognize the importance of lifestyle modifications for reducing CV risk. The Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High BP (JNC) VII guidelines recommend that treatment to meet BP targets should begin with lifestyle modification, including weight reduction, adoption of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) eating plan, reduction of dietary sodium, regular aerobic physical activity and moderation of alcohol consumption () (CitationChobanian et al 2003). The ESH-ESC and NCEP ATP III guidelines make similar recommendations (CitationNCEP Expert Panel 2002; ESH–ESC Guidelines Committee 2003). Smoking cessation programs are also integral to management of overall CV risk (ESH–ESC Guidelines Committee 2003), and provide one of the single most effective lifestyle changes that can be made to reduce the risk of non-CV and CV diseases () (CitationDoll et al 1994).

Obesity management

Obesity rates are increasing in epidemic proportions (CitationHedley et al 2004). Abdominal obesity is particularly strongly associated with CV risk and has been shown to increase the risk of ischemic stroke by approximately three-fold (CitationSuk et al 2003). As well as being a significant independent risk factor for CV disease, obesity is associated with an increased risk of developing other conditions associated with CV risk. Furthermore, in obese individuals there is a high likelihood that they will have insulin resistance (CitationMcLaughlin et al 2004), which puts them at an increased risk from type 2 diabetes (CitationGrundy 2005). The central role of obesity in the metabolic syndrome has been highlighted by the recent IDF definition for the metabolic syndrome (), which stipulates that for an individual to be diagnosed with the syndrome they must have central obesity, defined as waist circumference ≥94 cm for Europid men and ≥80 cm for Europid women, with ethnicity-specific values for other groups (CitationIDF 2006). Furthermore, a study of 22,171 men in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study showed that for every kilogram of weight gained, there was a 7.3% increase in the risk of developing diabetes (CitationKoh-Banerjee et al 2004). In this study, 56% of cases of diabetes were attributed to weight gain greater than 7 kg and 20% were attributed to a waist gain exceeding 2.5 cm. Whilst lifestyle modification remains the major approach to the management of obesity, a number of anti-obesity drugs are available or in development and may have a role in reducing CV risk in obese or overweight patients () (CitationKlein 2004). A meta-analysis of clinical trials showed that sibutramine, orlistat and topiramate all reduced bodyweight in obese patients, while sibutramine was also associated with small improvements in HDL cholesterol (HDL-C) and very small improvements in glycemic control in patients with diabetes () (CitationLi et al 2005).

As suggested for obesity, it is advocated that insulin resistance, as another underlying factor in the development of metabolic syndrome, is treated with lifestyle modification as first-line therapy in order to prevent the development of type 2 diabetes and reduce the risk of CV disease (CitationDaskalopoulou 2004; CitationZieve 2004; CitationWagh and Stone 2004; CitationGrundy 2005; CitationVitale 2006). However, when lifestyle modification is no longer able to arrest the rise in blood glucose towards diabetic levels and clustering of risk factors progresses, intervention with drugs directed towards the individual risk factors is essential () (CitationGrundy 2006).

BP lowering

Antihypertensive therapy to reduce BP is central to the management of CV risk and provides a starting point for initiating a more comprehensive CV risk management strategy (CitationChobanian 2003; CitationEl-Atat et al 2006; CitationEpstein 2006; CitationSowers 2006). The Joint European Societies Cardiovascular Disease Prevention guidelines specify BP targets of <140/90 mmHg for individuals with hypertension and no other risk factors and <130/80 mmHg for patients with diabetes or chronic kidney disease () (CitationDe Backer et al 2003; CitationErhardt and Gotto 2006). However, there is increasing evidence that even more aggressive BP targets may be warranted for patients at increased CV risk.

In a recent prospective cohort analysis among 8,960 middle-aged adults in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study, individuals with prehypertensive levels of BP were found to have an increased risk of developing CVD relative to those with optimal levels (CitationKshirsagar et al 2006). The association was found to be more pronounced among blacks, individuals with diabetes mellitus, and those with high BMI.

The ability to stratify patients according to their calculated total CV risk also questions whether high-risk patients, not classified as hypertensive, should also receive antihypertensive therapy (CitationMancia 2006). For example, a number of studies have shown that intensive BP lowering, even in patients whose baseline BP is <140/90 mmHg, is beneficial in high-risk patients, including those with diabetes (CitationYusuf et al 2000; PROGRESS Collaboration Group 2001; CitationSchrier et al 2002). Although guideline BP target recommendations have become more aggressive in recent years, these results combined with other existing data question whether current recommendations go far enough. Indeed, The Writing Group of the American Society of Hypertension (CitationGiles et al 2005) recently proposed a redefinition of hypertension away from arbitrary thresholds and towards overall CV risk status. Several of the current guidelines already recognize that patients with hypertension plus a cluster of risk factors require a total CV risk management strategy (ESH–ESC Guidelines Committee 2003; CitationChobanian 2003; CitationDe Backer et al 2003; CitationWhitworth et al 2003; CitationWilliams et al 2004; CitationBCS et al 2005; CitationCHS 2005). As further evidence accumulates, this may prompt a revision to guideline targets.

Dyslipidemia management

Several large, randomized, controlled trials have documented that cholesterol-lowering therapy with statins reduces the risk of death or CV events across a wide range of cholesterol levels, and that lipid management is integral to reducing CVD risk. In common with BP targets, lipid-lowering goals are also becoming more stringent. A recent analysis of the evolution of the Joint European Societies’ guidelines with respect to their lipid recommendations stresses the importance of lowering lipid levels to, or below, the currently recommended goals () (CitationErhardt 2006). It was argued that the patients’ global risk for CVD, rather than baseline lipid levels, should direct the intensity of lipid-lowering treatment.

There is evidence that more stringent targets than those currently recommended by international guidelines may result in greater reductions in CV risk. In the Heart Protection Study (HPS) – a landmark trial that looked at the effect of fixed-dose statin (simvastatin 40 mg/day) by low-density lipoprotein cholesterol LDL-C subgroups (LDL-C >135; 116–135; and <116) – significant LDL-C reductions were observed in each predefined LDL-C subgroup (LDL-C >135: 39%; LDL-C 116–135: 37%; and LDL-C <116: 35%) and these reductions correlated to comparable relative risk reductions (major vascular events: 19%, 26%, and 21%, respectively), irrespective of baseline LDL-C levels (CitationBrown 2002). Results from Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy (PROVE-IT) in patients with acute coronary syndrome (CitationWiviott et al 2006) and Treating to New Targets (TNT) (CitationLaRosa et al 2005) in patients with stable coronary artery disease, both showed that patients treated intensively to below target LDL levels experienced clinically significant benefits in CV outcomes.

Additionally, the recently published results from A Study to Evaluate the Effect of Rosuvastatin on Intravascular Ultrasound-Derived Coronary Atheroma Burden (ASTEROID) showed that intensive treatment with rosuvastatin resulted in a 53% reduction in LDL-C (from 130 mg/dL to 60.8 mg/dL) at 24 months and this was associated with significant regression of atherosclerosis, supporting the benefits of intensive lipid lowering (CitationNissen et al 2006).

Prevention of new-onset diabetes

Oral antidiabetic agents may provide a means to treat impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) and delay new-onset diabetes in patients with or without the metabolic syndrome (). In the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP), treatment with metformin reduced the risk of developing type 2 diabetes by 31%, compared with placebo, in patients with prediabetes (CitationKitabchi et al 2005). However, this reduction was smaller than that achieved with intensive lifestyle modification (58%). Recent thiazolidinedione studies have also demonstrated efficacy in delaying or preventing type 2 diabetes in patients with IGT and insulin resistance (CitationBuchanan et al 2002; CitationKnowler et al 2002). Other studies have shown that both acarbose and orlistat can be used to delay the development of type 2 diabetes in patients with IGT (CitationChiasson et al 2003; CitationTorgerson et al 2004). In addition, the Diabetes REduction Assessment with rAmipril and rosiglitazone Medication (DREAM) (ramipril and rosiglitazone) study which enrolled 5,269 adults with impaired fasting glucose (IFG) or IGT, showed that rosiglitazone reduced the risk of new type 2 diabetes by 60% (DREAM Trial Investigators 2006a). In contrast, although ramipril resulted in a significant number of patients achieving normoglycemia (p = 0.001 vs placebo), it did not significantly reduce the risk of developing type 2 diabetes (DREAM Trial Investigators 2006b).

In addition to the benefits of BP reduction per se, there is strong evidence that angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-Is) and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) are associated with a reduction in the risk of new-onset diabetes () (CitationMcCall et al 2006). However, recent data from the DREAM study showed that although the ACE-I ramipril modestly improved glycemic status in patients with IFG or IGT; it had no significant effect on the risk of new type 2 diabetes (DREAM Trial Investigators 2006b). More favorable results have been reported from studies of ARBs such as the Valsartan Antihypertensive Long-term Use Evaluation (VALUE) study, in which the ARB valsartan was found to reduce the risk of new-onset diabetes by 23% compared with the calcium channel blocker amlodipine in patients with hypertension and at high risk of cardiac events (CitationJulius et al 2004). Similarly, in the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension (LIFE) study, patients with hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy who received the ARB losartan had a 25% reduction in new-onset diabetes compared with patients receiving the β-blocker atenolol (Dahlöf et al 2002). Candesartan was also found to reduce the risk of new-onset diabetes by 25% in elderly patients with hypertension in the Study on Cognition and Prognosis in the Elderly (SCOPE) (CitationLithell et al 2003) and by 40% in patients with congestive heart failure in the Candesartan in Heart Failure Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity (CHARM)-preserved study (CitationYusuf et al 2003). In addition, the Antihypertensive treatment and Lipid Profile In a North of Sweden Efficacy Evaluation (ALPINE) study showed that candesartan was associated with new diagnoses of type 2 diabetes in only one of 197 patients, compared with eight of 196 patients receiving hydrochlorothiazide (CitationLindholm et al 2003).

Currently, there is little or no evidence that preventing diabetes will translate into subsequent prevention of CV events. As such, it remains unproven that patients would benefit from diabetes prevention in terms of reductions in CV events. The ongoing Nateglinide And Valsartan in Impaired Glucose Tolerance Outcomes Research (NAVIGATOR) trial in patients with IGT and CVD or at CV risk, the largest diabetes trial with an ARB conducted to date, is the only diabetes prevention study also powered to show a reduction in CVD and will provide important information on this topic.

Management issues

Awareness and detection of risk factors

Effective management of CV risk and metabolic disease through intensive treatment of multiple risk factors must overcome several key obstacles. Firstly, the risk factors need to be detected earlier and quantified. Rates of detection and treatment of CV risk factors are low. For example, as part of the Multinational MONItoring of trends and determinants in CArdiovascular disease (MONICA) study, it was found that in Northern Sweden, only 50% of individuals with hypertension received treatment and the majority of these patients were uncontrolled(CitationJansson et al 2003). Europe-wide data from MONICA showed that awareness of hypercholesterolemia varied considerably between populations, with 3%–62% of men and 0%–65% of women being aware of their elevated cholesterol (CitationTolonen et al 2005). Low levels of awareness result in low levels of treatment: in the MONICA study only 45% of men and 44% of women were receiving treatment for their hypercholesterolemia. Public health education plays an integral part in raising awareness about CV risk factors.

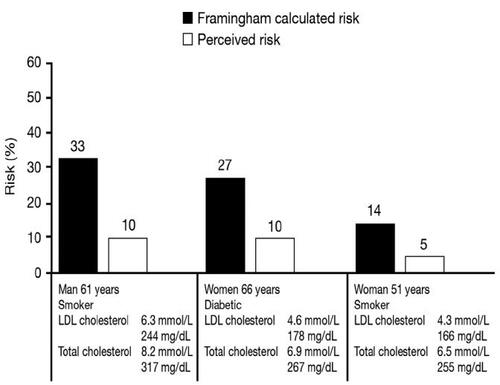

Improved screening for CV risk factors and the metabolic syndrome is vital if long-term reductions in overall morbidity and mortality are to be achieved. Many CV risk factors (such as hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, or IGT) are ‘silent’ and individuals will not necessarily be aware that they are at an increased risk. Reducing overall CV risk therefore needs to begin by evaluating all known modifiable risk factors so that a detailed CV and metabolic risk-status profile can be created and appropriate management implemented. Secondly, while many individuals recognize that their behavior is associated with increased CV risk, there is often a lack of motivation to make lifestyle changes. Strategies such as motivational interviewing (CitationShinitzky and Kub 2001) and improving community opportunities for physical activity can be effective at helping patients to implement and maintain lifestyle changes. Thirdly, physicians need to recognize the importance of early and aggressive treatment and make appropriate therapeutic interventions based on current guidelines and accurate risk assessment. However, physicians’ assessments of CV risk may deviate significantly from scores measured using the risk charts, suggesting that initiatives are needed to promote accurate risk assessment techniques (CitationMosca et al 2005). Generally, primary care physicians seem to underestimate total CV risk (), thus making the use of tools to assess the CV risk important in clinical practice (CitationBacklund et al 2004).

Figure 4 Comparison of actual versus perceived 10-year risk among 80 Swedish general practitioners when asked to estimate the risk of specific patient profiles. Data drawn from CitationBacklund L, Bring J, Strender L-E. 2004. How accurately do general practitioners and students estimate coronary risk in hypercholesterolaemic patients? Primary Health Care Research and Development, 5:145–52.

Future algorithms need to be able to assess lifetime risk and guide the clinician toward optimal treatment, even if, as in younger individuals, the 10-year risk of CV events is not excessively high.

Compliance and persistence

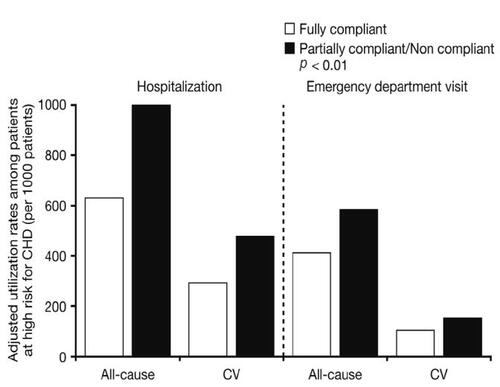

Once pharmacological interventions have been prescribed, patients need to exhibit a high level of compliance and persistence in order to derive optimal benefit from the therapy. It has been estimated that poor therapeutic compliance contributes to lack of BP control in over two-thirds of patients with hypertension, while up to half of patients receiving antihypertensive drugs discontinue treatment within 6 months to 4 years (CitationAnonymous 2005). This lack of compliance can invariably lead to increased resource utilization, which in turn, will lead to increased economic burden () (CitationGoldman et al 2006). Improved compliance to medication significantly reduces this burden. Prescription patterns among primary care physicians have been shown to influence discontinuation of medication and general practitioners with high levels of prescribing attain higher rates of early discontinuation compared with colleagues with low levels of prescribing (CitationHansen at al 2007). Strategies that have been shown to improve compliance and persistence include the use of drugs with convenient dosing regimens and better tolerability profiles, however, the importance of adherence still needs to be reinforced by governmental and health agencies.

Figure 5 Emergency resource utilization in fully compliant and partial/non compliant patients with high risk for coronary heart disease. Data drawn from CitationGoldman DP, Joyce GF, Karaca-Mandic P. 2006. Varying pharmacy benefits with clinical status: the case of cholesterol-lowering therapy. Am J Manag Care, 12:21–8.

Conclusions

Cardiovascular disease and metabolic disease are characterized by multiple concurrent and interrelated causes. Many risk factors for CVD can be treated effectively with existing, well-tolerated pharmacotherapies. There is now convincing evidence of the need for an early, intensive, and integrated approach to the management of multiple risk factors for CV disease to reduce the long-term clinical burden. Risk-factor screening, recognition of risk factor clustering and an integrated approach to multiple risk management, together with government and health agency driven public education, should result in reductions in total CV and metabolic risk, with concurrent clinical and economic benefits.

Acknowledgements

The author was assisted in the preparation of this text by professional medical writer Christine Arris (ACUMED); this support was funded by Novartis Pharma AG.

References

- No authors listedAfter the diagnosis: adherence and persistence with hypertension therapyAm J Manag Care200511S395S39916300455

- AthyrosVGMikhailidisDPPapageorgiouAATargeting vascular risk in patients with metabolic syndrome but without diabetesMetabolism20055410657416092057

- BacklundLBringJStrenderL-EHow accurately do general practitioners and students estimate coronary risk in hypercholesterolaemic patients?Primary Health Care Research and Development2004514552

- Baena DiezJMAlvarezPBPinolFPAssociation between clustering of cardiovascular risk factors and the risk of cardiovascular diseaseRev Esp Salud Publica20027671511905401

- British Cardiac Society, [BCS], British Hypertension Society, Diabetes UKJBS 2: Joint British Societies’ guidelines on prevention of cardiovascular disease in clinical practiceHeart200591Suppl 5v15216365341

- BrownMJMRC/BHF Heart Protection StudyLancet20023601782412480451

- BuchananTAXiangAHPetersRKPreservation of pancreatic beta-cell function and prevention of type 2 diabetes by pharmacological treatment of insulin resistance in high-risk hispanic womenDiabetes200251279680312196473

- Canadian Hypertension Society [CHS]CHEP Recommendations for the management of hypertension [online]2005 Accessed on April 10, 2007. URL: http://www.hypertension.ca/recommendations_2005/ultrashortexecsummary2005.pdf

- CheungBMOngKLManYBPrevalence of the metabolic syndrome in the United States national health and nutrition examination survey 1999 – 2002 according to different defining criteriaJ Clin Hypertens (Greenwich)200685627016896272

- ChiassonJLJosseRGGomisRAcarbose treatment and the risk of cardiovascular disease and hypertension in patients with impaired glucose tolerance: the STOP-NIDDM trialJAMA20032904869412876091

- ChobanianAVBakrisGLBlackHRSeventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood PressureHypertension20034212065214656957

- ConroyRMPyoralaKFitzgeraldAPEstimation of ten-year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in Europe: the SCORE projectEur Heart J200324987100312788299

- CsaszarAKekesEAbelTPrevalence of metabolic syndrome estimated by International Diabetes Federation criteria in a Hungarian populationBlood Press200615101616754273

- DahlofBDevereuxRBKjeldsenSECardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension study (LIFE): a randomised trial against atenololLancet2002359995100311937178

- DaskalopoulouSSMikhailidisDPElisafMPrevention and treatment of the metabolic syndromeAngiology20045558961215547646

- De BackerGAmbrosioniEBorch-JohnsenKEuropean guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: third joint task force of European and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (constituted by representatives of eight societies and by invited experts)Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil200310S1S1014555889

- DollRPetoRWheatleyKMortality in relation to smoking: 40 years’ observations on male British doctorsBMJ1994309901117755693

- DREAM Trial InvestigatorsEffect of Ramipril on the incidence of diabetesN Engl J Med2006355 Sep 15 [Epub ahead of print].(b)

- DREAM Trial InvestigatorsEffect of rosiglitazone on the frequency of diabetes in patients with impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose: a randomised controlled trialLancet2006368109610516997664

- ElabbassiWNHaddadHAThe epidemic of the metabolic syndromeSaudi Med J200526373515806201

- El-AtatFMc/FarlaneSISowersJRDiabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular derangements: pathophysiology and managementCurr Hypertens Rep200662152315128475

- EpsteinMDiabetes and hypertension: the bad companionsJ Hypertens200615S55S62

- ErhardtLRGottoAJrThe evolution of European guidelines: changing the management of cholesterol levelsAtherosclerosis2006185122016309687

- ESH/ESC Guidelines CommitteeEuropean Society of Hypertension-European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the management of arterial hypertensionJ Hypertens20032110115312777938

- FordESGilesWHMokdadAHIncreasing prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among U.S. adultsDiabetes Care2004272444915451914

- FordESPrevalence of the metabolic syndrome defined by the International Diabetes Federation among adults in the USDiabetes Care2005282745916249550

- GilesTDBerkBCBlackHRExpanding the definition and classification of hypertensionJ Clin Hypertens (Greenwich)200575051216227769

- GoldmanDPJoyceGFKaraca-MandicPVarying pharmacy benefits with clinical status: the case of cholesterol-lowering therapyAm J Manag Care20061221816402885

- GreenlandPKnollMDStamlerJMajor risk factors as antecedents of fatal and nonfatal coronary heart disease eventsJAMA2003290891712928465

- GrundySMMetabolic syndrome: therapeutic considerationsHandb Exp Pharmacol20051701073316596797

- GrundySMMetabolic syndrome: connecting and reconciling cardiovascular and diabetes worldsJ Am Coll Cardiol200647109310016545636

- GuDGuptaAMuntnerPPrevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factor clustering among the adult population of China: results from the International Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease in Asia (InterAsia)Circulation20051126586516043645

- HackamDGAnandSSEmerging Risk Factors for Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease: A Critical Review of the EvidenceJAMA20032909324012928471

- HansenDGGichangiAVachWEarly discontinuation: more frequent among general practitioners with high levels of prescribingEur J Clin Pharmacol200763861517618428

- HansonRLImperatoreGBennettPHComponents of the “metabolic syndrome” and incidence of type 2 diabetesDiabetes2002513120712351457

- HedleyAAOgdenCLJohnsonCLPrevalence of overweight and obesity among US children, adolescents, and adults, 1999–2002JAMA200429128475015199035

- HubertHBFeinleibMMcNamaraPMObesity as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease: a 26-year follow-up of participants in the Framingham Heart StudyCirculation198367968776219830

- International Diabetes Federation, [IDF]The IDF consensus worldwide definition of the metabolic syndrome2006 Accessed on April 10, 2007. URL: http://http://www.idf.org/webdata/docs/IDF_Meta_def_final.pdf

- JanssonJHBomanKMessnerTTrends in blood pressure, lipids, lipoproteins and glucose metabolism in the Northern Sweden MONICA project 1986–99Scand J Public Health Suppl200361435014660247

- JuliusSKjeldsenSEWeberMOutcomes in hypertensive patients at high cardiovascular risk treated with regimens based on valsartan or amlodipine: the VALUE randomised trialLancet200436320223115207952

- KitabchiAETemprosaMKnowlerWCRole of insulin secretion and sensitivity in the evolution of type 2 diabetes in the diabetes prevention program: effects of lifestyle intervention and metforminDiabetes20055424041416046308

- KleinSLong-term pharmacotherapy for obesityObes Res200412Suppl163S166S15687412

- KnowlerWCBarrett-ConnorEFowlerSEReduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metforminN Engl J Med200234639340311832527

- Koh-BanerjeePWangYHuFBChanges in body weight and body fat distribution as risk factors for clinical diabetes in US menAm J Epidemiol20041591150915191932

- KshirsagarAVCarpenterMBangHBlood pressure usually considered normal is associated with an elevated risk of cardiovascular diseaseAm J Med20061191334116443415

- LaaksonenDELakkaHMNiskanenLKMetabolic syndrome and development of diabetes mellitus: application and validation of recently suggested definitions of the metabolic syndrome in a prospective cohort studyAm J Epidemiol20021561070712446265

- LakkaHMLaaksonenDELakkaTAThe metabolic syndrome and total and cardiovascular disease mortality in middle-aged menJAMA200228827091612460094

- LaRosaJCGrundySMWatersDDIntensive lipid lowering with atorvastatin in patients with stable coronary diseaseN Engl J Med200535214253515755765

- LiZMaglioneMTuWMeta-analysis: pharmacologic treatment of obesityAnn Intern Med20051425324615809465

- LindholmLHPerssonMAlaupovicPMetabolic outcome during 1 year in newly detected hypertensives: results of the Antihypertensive Treatment and Lipid Profile in a North of Sweden Efficacy Evaluation (ALPINE study)J Hypertens20032115637412872052

- LithellHHanssonLSkoogIThe Study on Cognition and Prognosis in the Elderly (SCOPE): principal results of a randomized double-blind intervention trialJ Hypertens2003218758612714861

- ManciaGTotal cardiovascular risk: a new treatment conceptJ Hypertens Suppl200624S17S2416601556

- McCallKLCraddockDEdwardsKEffect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers on the rate of new-onset diabetes mellitus: a review and pooled analysisPharmacotherapy200626129730616945052

- McLaughlinTAbbasiFChealKUse of metabolic markers to identify overweight individuals who are insulin resistantAnn Intern Med2003139802914623617

- McLaughlinTAllisonGAbbasiFPrevalence of insulin resistance and associated cardiovascular disease risk factors among normal weight, overweight, and obese individualsMetabolism200453495915045698

- MoscaLLinfanteAHBenjaminEJNational study of physician awareness and adherence to cardiovascular disease prevention guidelinesCirculation200511149951015687140

- NCEP Expert PanelThird Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final reportCirculation2002106314342112485966

- NinomiyaJKL’ItalienGCriquiMHAssociation of the metabolic syndrome with history of myocardial infarction and stroke in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination SurveyCirculation200410942614676144

- NissenSENichollsSJSipahiIEffect of very high-intensity statin therapy on regression of coronary atherosclerosis: the ASTEROID trialJAMA200629515566516533939

- PROGRESS Collaborative GroupRandomised trial of a perindopril-based blood-pressure-lowering regimen among 6, 105 individuals with previous stroke or transient ischaemic attackLancet200135810334111589932

- SchrierRWEstacioROEslerAEffects of aggressive blood pressure control in normotensive type 2 diabetic patients on albuminuria, retinopathy and strokesKidney Int20026110869711849464

- SeverPSDahlofBPoulterNRPrevention of coronary and stroke events with atorvastatin in hypertensive patients who have average or lower-than-average cholesterol concentrations, in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial—Lipid Lowering Arm (ASCOT-LLA): a multicentre randomised controlled trialLancet200336111495812686036

- ShinitzkyHEKubJThe art of motivating behavior change: the use of motivational interviewing to promote healthPublic Health Nurs2001181788511359619

- SowersJRRecommendations for special populations: diabetes melitus and the metabolic syndromeAm J Hypertens200616S41S45

- StamlerJVaccaroONeatonJDDiabetes, other risk factors, and 12-yr cardiovascular mortality for men screened in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention TrialDiabetes Care199316434448432214

- SukSHSaccoRLBoden-AlbalaBAbdominal obesity and risk of ischemic stroke: the Northern Manhattan Stroke StudyStroke200334715869212775882

- ThomasFRudnichiABacriAMCardiovascular mortality in hypertensive men according to presence of associated risk factorsHypertension20013712566111358937

- TolonenHKeilUFerrarioMEvansAPrevalence, awareness and treatment of hypercholesterolaemia in 32 populations: results from the WHO MONICA ProjectInt J Epidemiol2005341819215333620

- TorgersonJSHauptmanJBoldrinMNXENical in the prevention of diabetes in obese subjects (XENDOS) study: a randomized study of orlistat as an adjunct to lifestyle changes for the prevention of type 2 diabetes in obese patientsDiabetes Care2004271556114693982

- VitaleCMarazziGVolterraniMMetabolic syndromeMinerva Med2006972192916855517

- VolpeMTocciGIntegrated cardiovascular risk management for the future: lessons learned from the ASCOT trialAging Clin Exp Res200617465316640173

- WaghAStoneNJTreatment of metabolic syndromeExpert Rev Cardiovasc Ther200422132815151470

- WhitworthJA2003 World Health Organization (WHO)/International Society of Hypertension (ISH) statement on management of hypertensionJ Hypertens20032119839214597836

- WildSHByrneCDByrneCDWildSHThe global burden of the metabolic syndrome and its consequences for diabetes and cardiovascular diseaseThe Metabolic Syndrome2005ChichesterJohn Wiley & Sons Ltd143

- WilliamsBPoulterNRBrownMJGuidelines for management of hypertension: report of the fourth working party of the British Hypertension Society, 2004-BHS IVJ Hum Hypertens2004181398514973512

- WiviottSDde LemosJACannonCPA tale of two trials: a comparison of the post-acute coronary syndrome lipid-lowering trials A to Z and PROVE IT-TIMI 22Circulation200611314061416534008

- World Health Organization, [WHO]The European Health Report2002 Accessed on April 10, 2007. URL: http://http://www.euro.who.int/europeanhealthreport

- YusufSHawkenSOunpuuSEffect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control studyLancet20043649375215364185

- YusufSPfefferMASwedbergKEffects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved left-ventricular ejection fraction: the CHARM-Preserved TrialLancet20033627778113678871

- YusufSSleightPPogueJEffects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study InvestigatorsN Engl J Med20003421455310639539

- ZieveFJThe metabolic syndrome: diagnosis and treatmentClin Cornerstone20046Suppl 3S5S1315707265