Abstract

Drinking games are high-risk, social drinking activities comprised of rules that promote participants’ intoxication and determine when and how much alcohol should be consumed. Despite the negative consequences associated with drinking games, this high-risk activity is common among college students, with participation rates reported at nearly 50% in some studies. Empirical research examining drinking games participation in college student populations has increased (i.e. over 40 peer-reviewed articles were published in the past decade) in response to the health risks associated with gaming and its prevalence among college students. This Special Issue of The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse seeks to advance the college drinking games literature even further by addressing understudied, innovative factors associated with the study of drinking games, including the negative consequences associated with drinking games participation; contextual, cultural, and psychological factors that may influence gaming; methodological concerns in drinking games research; and recommendations for intervention strategies. This Prologue introduces readers to each article topic-by-topic and underscores the importance of the continued study of drinking games participation among college students.

Introduction

In light of the high prevalence of alcohol use and alcohol-related problems experienced by college students in the past several years (Citation1,Citation2), alcohol researchers have paid close attention to college students’ participation in high-risk drinking behaviors. One such high-risk behavior is drinking games participation. Drinking games can be defined as a social drinking activity that encourages intoxication by governing players’ alcohol consumption through the use of rules that specify when to drink and how much to consume (Citation3). These explicit rules are what make drinking games a uniquely high-risk drinking activity. These rules also provide a context in which to understand the high-risk nature of drinking games: the extent to which the rules facilitate heavy drinking, the amount of personal discomfort participants experience as a result of breaking these rules, and the degree to which other participants enforce them. Following the rules and “playing the game” often leads to more harm than good.

Drinking game participants are also often required to perform cognitive and/or motor tasks that range from passive activities, such as following verbal cues that dictate when to drink (e.g. drinking every time a television character says a certain phrase), to more active tasks, such as attempting to get a ping pong ball inside a cup (e.g. beer pong) (Citation3). Drinking games tend to be risky, as the rules of such games encourage intoxication through rapid and/or substantial alcohol intake. Despite the health risks associated with this activity (Citation4–6), many college students play drinking games, with prevalence rates reported at almost 50% in a large, multi-site sample [(Citation4); see Zamboanga et al. (Citation7) for a recent review on drinking games]. Moreover, in contrast to other high-risk drinking activities [e.g. pregaming/prepartying, or drinking before going out, Borsari et al. (Citation8); tailgating, or drinking before attending a football game, Hustad et al. (Citation9); 21st birthday celebrations, Rutledge et al. (Citation10)], some participants may not have total control over how much they drink because their consumption is determined by the rules of the game and/or other participants’ behavior (e.g. targeting other gamers to drink).

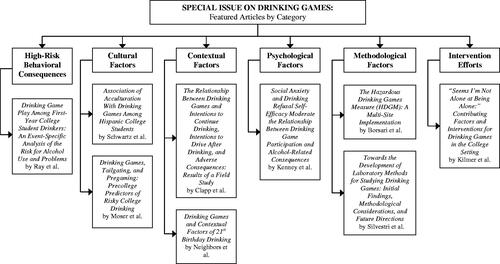

During the past decade, over 40 empirical articles examining drinking game behaviors among college students have been published in peer-reviewed journals (Citation7). The articles included in this Special Issue are designed to further contribute to and advance the drinking games literature in a number of important ways, with each paper focusing on an understudied and/or innovative factor related to drinking games participation in college students (see for an overview of the categories of articles featured in this Special Issue). Taken together, the included articles address the consequences of drinking games participation; the contextual, cultural, and psychological factors that impact drinking game behaviors; methodological concerns in drinking games research; and recommendations for intervention strategies.

Figure 1. Featured articles by category. Articles are organized according to some (if not most) of their key findings.

This Special Issue opens with a study by Ray et al. (Citation11). Using an event-specific design, Ray and colleagues highlight the high-risk nature of drinking games participation, regardless of individuals’ typical quantity of alcohol use and frequency of gaming. Event-specific research is a relatively new, innovative approach to the study of high-risk drinking that utilizes data pertaining to specific drinking occasions. This approach is especially useful for investigating the association between certain variables and specific events or contexts (e.g. a 21st birthday celebration, a college party, etc.), rather than simply investigating aggregate trends.

The associations between ethnic/cultural factors and drinking games participation have been relatively understudied in the drinking games literature. Only two studies to date have examined ethnicity and its relevance to drinking games involvement (Citation12,Citation13). In addition, research that has examined the role of culture and/or acculturation [i.e. the cultural, psychological, and social change and adaptation that takes place when culturally dissimilar individuals or groups come in contact; (Citation14)] in drinking game behaviors has been, up until now, non-existent. Using a large, multi-site sample, Schwartz et al. (Citation15) herein employed a bidimensional approach to examine how different aspects of acculturation (i.e. values, identifications, and practices) are associated with drinking game behaviors for Hispanic men and women. Another cultural consideration in respect to drinking games participation is the kind of cultural adjustment that can take place during the transition into college, or the internalization of the college drinking culture (ICDC). ICDC is a relatively new construct that has the potential to help improve targeted interventions prior to and during college. As such, Moser et al. (Citation16) examined ICDC (in addition to other psychological and social factors) and their relevance to drinking game behaviors.

To date, it has been extremely challenging to disentangle the unique and complementary features of drinking games from other high-risk drinking activities that occur on college campuses (e.g. pregaming/prepartying, tailgating, and/or 21st birthday celebrations). Therefore, this Special Issue includes papers that use event-specific designs to investigate contextual factors associated with drinking game behaviors. Clapp et al.’s study (Citation17) is the first to examine drinking games in the context of a real party, and Neighbors et al.’s study (Citation18) assesses drinking games that take place during 21st birthday celebrations. Research investigating drinking games behavior in the context of 21st birthday celebrations is particularly important given that students are at increased risk for heavy alcohol consumption on this occasion.

With regard to psychological variables, Kenney et al. (Citation19) examined social anxiety and drinking refusal self-efficacy. Kenney et al. (Citation19) refines our understanding of the intersection between social anxiety and alcohol cognitions in respect to drinking games. Such research is important, as socially anxious students may avoid playing drinking games out of fear that they will embarrass themselves while playing (Citation20) or may be more inclined to play drinking games since they facilitate rapid intoxication within a structured social context, thus alleviating anxiety (Citation7,Citation21). Drinking refusal self-efficacy and social anxiety may be especially important to consider as moderators of the association between drinking games participation and negative drinking consequences because socially anxious students may not be confident in their ability to refuse alcohol in the face of social pressure, thereby potentially increasing their risk for negative outcomes (Citation19).

This Special Issue also outlines a number of important, innovative methodological approaches to studying drinking games. Until recently, there was no standardized measure of drinking games involvement. In a recent paper outside of this Special Issue, Borsari et al. (Citation22) described the Hazardous Drinking Games Measure (HDGM), the first published attempt at standardizing drinking game behaviors. In this Special Issue, Borsari et al. (Citation23) now presents data on the HDGM in multiple samples of college students. In addition, Silvestri et al. (Citation24) discuss another important methodological advancement in the study of drinking games: the Simulated Drinking Games Procedure (SDGP). These investigators outline how to conduct drinking games research using the SDGP in a laboratory setting and discuss the strengths and limitations associated with this method. Studying drinking games using experimental designs like the SDGP will enable the systematic manipulation of variables that might impact gaming behaviors as well as allow control over factors that can affect measurement (e.g. accurate assessment/recall of the quantity of alcohol consumed while playing)

The last article in this Special Issue, by Kilmer et al. (Citation25), examines the long-standing, ubiquitous nature of drinking games, the ways in which this activity can facilitate social interactions, and the influence of perceived social norms on the prevalence of drinking games participation. Kilmer and colleagues also briefly discuss the existing, albeit limited, intervention studies that have included drinking games participation as an outcome variable. Importantly, they highlight promising directions for future intervention strategies designed to target this behavior. Finally, this Special Issue concludes with an epilogue by Jennifer P. Read (Citation26), who highlights the major themes that tie these articles together, such as gender, contextual factors, positive and negative reinforcement, and their relevance to drinking games participation.

In closing, it is our hope that the articles included in this Special Issue will help sustain interest in the study of drinking games, increase awareness of the adverse health consequences of this popular activity (which may also occur alongside other high-risk drinking behaviors), bring attention to novel approaches to the study of drinking games, and highlight the relevance of cultural, contextual, and psychological factors that can influence gaming behavior.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Brian Borsari, PhD, Janine V. Olthuis, PhD, Seth J. Schwartz, PhD, and Kathryne Van Hedger, MA, for their editorial feedback on earlier drafts of this manuscript. The authors would also like to acknowledge the many individuals whose time, effort, and hard work have made this Special Issue on drinking games possible. Thank you to the following peer reviewers for their invaluable feedback on the manuscripts included in this Special Issue: Cathy Lau-Barraco, PhD, Heidemarie Blumenthal, PhD, Carlo C. DiClemente, PhD, Phillip J. Ehret, BA, Joel R. Grossbard, PhD, Lindsay S. Ham, PhD, Mark E. Johnson, PhD, Shannon R. Kenney, PhD, Elma I. Lorenzo-Blanco, PhD, Jennifer E. Merrill, PhD, Rebecca L. Monk, PhD, Timothy M. Osberg, PhD, Assaf Oshri, PhD, Aesoon Park, PhD, Philip K. Peake, PhD, Jennifer P. Read, PhD, Patricia C. Rutledge, PhD, and Dennis L. Thombs, PhD. Special thanks to Cara C. Tomaso for her outstanding job as an editorial assistant for this Special Issue. Thank you to Amie L. Haas, PhD, for her feedback and assistance with planning during the early stages of this Special Issue. Thank you to Dawn Hunter for her assistance in promoting this Special Issue. Thank you to Robbi Banks and Simone Skeen for their editorial assistance and help with troubleshooting. Finally, special thanks to Bryon Adinoff, MD, for the opportunity to make this Special Issue possible and for his feedback, guidance, and assistance throughout the editorial process.

References

- Mallett KA, Varvil-Weld L, Read JP, Neighbors C, White HR. An update of research examining college student alcohol-related consequences: new perspectives and implications for interventions. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2013;37:709–716

- Hingson RW, Zha W, Weitzman ER. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24, 1998–2005. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2009;16(SupplCollege Drinking Games (Guest Editor: Byron Zamboanga, Cara Tomaso)):12–20

- Zamboanga BL, Pearce MW, Kenney SR, Ham LS, Woods OE, Borsari B. Are “extreme consumption games” drinking games? Sometimes it’s a matter of perspective. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2013;39:275–279

- Grossbard J, Geisner IR, Neighbors C, Kilmer JR, Larimer ME. Are drinking games sports? College athlete participation in drinking games and alcohol-related problems. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2007;68:97–105

- Polizzotto MN, Saw MM, Tjhung I, Chua EH, Stockwell TR. Fluid skills: drinking games and alcohol consumption among Australian university students. Drug Alcohol Rev 2007;26:469–475

- Johnson TJ, Stahl C. Sexual experiences associated with participation in drinking games. J Gen Psychol 2004;131:304–320

- Zamboanga BL, Olthuis JV, Kenney SR, Correia CJ, Van Tyne K, Ham LS, Borsari B. Not just fun and games: a review of drinking games research from 2004–2013. Psychol Addict Behav. [in press]

- Borsari B, Boyle KE, Hustad JTP, Barnett NP, O’Leary Tevyaw T, Kahler CW. Drinking before drinking: pregaming and drinking games in mandated students. Addict Behav 2007;32:2694–2705

- Hustad JTP, Mastroleo NR, Urwin R, Zeman S, LaSalle L, Borsari B. Tailgating and pregaming by college students with alcohol offenses: Patterns of alcohol use and beliefs. Subst Use Misuse (in press)

- Rutledge PC, Park A, Sher KJ. 21st birthday drinking: extremely extreme. J Consult Clin Psychol 2008;76:511–516

- Ray AE, Stapleton JL, Turrisi R, Mun E. Drinking game play among first-year college student drinkers: an event-specific analysis of the risk for alcohol use and problems. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2014;40:353–358

- Haas AL, Smith SK, Kagan K, Jacob T. Pre-college pregaming: practices, risk factors, and relationship to other indices of problematic drinking during the transition from high school to college. Psychol Addict Behav 2012;26:931–938

- Pedersen ER, LaBrie J. Partying before the party: examining prepartying behavior among college students. J Am Coll Health 2006;56:237–245

- Zamboanga BL, Tomaso CC, Kondo KK, Schwartz SJ. Surveying the literature on acculturation and alcohol use among Hispanic college students: we’re not all on the same page. Subst Use Misuse 2014;49:1074–1078

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, Tomaso CC, Kondo KK, Unger JB, Weisskirch RS, Ham LS, et al. Domains of acculturation and their relevance to drinking games involvement and alcohol-related behaviors among Hispanic college students. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2014;40:359–366

- Moser K, Pearson MR, Hustad JTP, Borsari B. Drinking games, tailgating, and pregaming: precollege predictors of risky college drinking. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2014;40:367–373

- Clapp JD, Reed MB, Ruderman DE. The relationship between drinking games and intentions to continue drinking, intentions to drive after drinking, and adverse consequences: results of a field study. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2014;40:374–379

- Neighbors C, Rodriguez L, Rinker D, DiBello AM, Young CM, Chen C. Drinking games and contextual factors of 21st birthday drinking. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2014;40:380–387

- Kenney SR, Napper LE, LaBrie JW. Social anxiety and drinking refusal self-efficacy moderate the relationship between drinking game participation and alcohol-related consequences. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2014;40:388–394

- Borsari B. Drinking games in the college environment: a review. J Alcohol Drug Educ 2004;48:29–51

- Ham LS, Zamboanga BL, Olthuis JV, Casner HG, Bui N. No fear, just relax and play: social anxiety, alcohol expectancies, and drinking games among college students. J Am Coll Health 2010;58:473–479

- Borsari B, Zamboanga BL, Correia CJ, Olthuis JV, Van Tyne K, Zadworny Z, Grossbard JR, Horton NJ. Characterizing high school students who play drinking games using latent class analysis. Addict Behav 2013;38:2532–2540

- Borsari B, Peterson C, Zamboanga BL, Correia CJ, Olthuis JV, Ham LS, Grossbard J. The Hazardous Drinking Games Measure (HDGM): a multi-site implementation. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2014;40:395–402

- Silvestri M, Lewis JM, Borsari B, Correia CJ. Towards the development of laboratory methods for studying drinking games: initial findings, methodological considerations, and future directions. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2014;40:403–410

- Kilmer JR, Cronce JM, Logan DE. “Seems I’m not alone at being alone.” Contributing factors and interventions for drinking games in the college setting. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2014;40:411–414

- Read JP. What's in a game? Future directions for the assessment and treatment of drinking games. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2014;40:415–418