Abstract

Society in America, like many others, continues to wrestle with the problem of misuse and abuse of prescription opioids. The implications of this struggle are widespread and involve many individuals and institutions including healthcare policymakers. State Medicaid pharmacy programs, in particular, undergo significant scrutiny of their programs to curtail this problem. While recent efforts have been made by government agencies to both quantify and offer methods for curbing this issue, it still falls to each state’s policymakers to protect its resources and the population it serves from the consequences of misuse and abuse. This paper details the history of one state Medicaid’s management of this issue at the pharmacy benefit level. Examples of various methods employed and the results are outlined and commentary is provided for each method. Regardless of the methods used to address this issue, the problem must still be a priority at all levels, not just for payers.

Introduction

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) stated in January 2012 that state Medicaid programs are seeing increases in drug diversion (defined as:“diversion of licit drugs for illicit purposes”) (Citation1). Diversion is a form of prescription drug abuse. Use of prescription drugs for reasons other than originally intended or by persons other than for whom prescribed can be considered misuse and abuse. This struggle with misuse and abuse of prescription opioids is not new. The problem is societal in nature, with implications for all entities from individuals to governments. The source and payment of prescription products abused makes prescription opioid misuse and abuse unique compared to other types of illicit drug use (Citation2). Though theft is one way for prescription drugs to end up “on the street”, diversion through normal distribution channels also occurs. When such diversion occurs, payment for the prescription products is often through legitimate third party payers such as commercial or government-sponsored insurance, like Medicaid or Medicare (Citation1). In a study by McAdam-Marx et al., costs for Medicaid patients with abuse/dependence-related diagnoses were higher than costs for patients without a related diagnosis. The authors suggest interventions targeted at preventing abuse and managing comorbidities in these patients can reduce costs and potential abuse (Citation3).

Suggested methods for intervention were proposed by Katz et al. based on a meeting sponsored by Tufts Health Care Institute Program on Opioid Risk Management. Proposed methods included pharmacy and prescriber controls, promotion of abuse-deterrent opioid products, monitoring of prescription claims, data sharing among insurance providers, and promoting strategies at the provider level to reduce risk of abuse (Citation2).

Over the past 10 years, Oklahoma Medicaid (MOK) has considered misuse and abuse of prescription narcotics a priority area of concern. At least nine unique prescription policies for opioid products were recommended by the Drug Utilization Review (DUR) Board and implemented by the Oklahoma Health Care Authority (OHCA)with the goal of decreasing misuse and abuse of opioids. The objective of this paper was to discuss the historical steps which MOK has taken to limit potential misuse and abuse of opioids.

Review of Oklahoma Medicaid policies

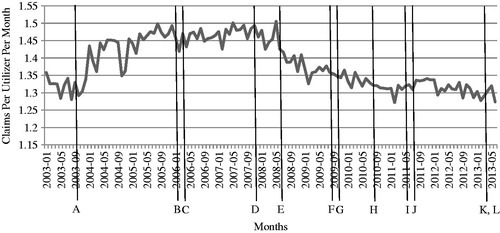

The policies that the DUR Board developed for OHCA’s SoonerCare pharmacy benefit program are listed in and discussed further below. Each policy has an alphabetical identifier which correlates with the graph in . This figure demonstrates the trend in opioid prescription claims over time. The vertical lines on indicate the points of policy implementation.

Figure 1. Opioid prescription claims per utilizer per month. Each letter corresponds to a policy listed in .

Table 1. List of Oklahoma SoonerCare policy implementations and dates.

Quantity limits

Total quantity allowed on a single prescription claim is a standard control measure used by pharmacy benefit managers to reduce over-utilization across therapeutic categories in their programs. The limit is typically set based on maximum daily dosage or duration approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The first opioid products given quantity limits by MOK were butorphanol nasal spray, fentanyl transdermal and oral products, hydromorphone, methadone, meperidine, and oxycodone immediate and controlled-release products in October 2003 (, Identifier A). Quantity limits were applied to other products in subsequent years until all opioid products were included (, Identifier G).

Pharmacy Lock-In program

Lock-In programs, common to all Medicaid and some commercial insurance plans, typically function by creating a prescription gatekeeper for beneficiaries who are deemed to have potential for misuse of their prescription benefits based on their prescription and medical services utilization history. Most programs include at minimum a restriction to a single pharmacy for these beneficiaries and may include a single physician source that also controls access to other health care services. A few states restrict members to a specific hospital for emergency services. While the research regarding the effectiveness of these programs is limited, the states which studied their effect found reductions in opioid utilization (Citation4–6).

MOK transferred the responsibility for the program to their DUR vendor in January 2006 (, Identifier B). An evaluation of the program found mean monthly opioid prescriptions were reduced after a beneficiary was locked-in to a single pharmacy, with no apparent effect on non-opioid related medications (Citation7). The results of the analysis indicated the average per member per month (PMPM) number of opioid prescription claims decreased by 0.09 (p < 0.0001) while there was no statistically significant change in the PMPM for the number of medications considered by the MOK DUR Board as maintenance for chronic disease states (, Identifier B). However, this study was unable to determine if the Lock-In program changed actual behavior outside of the patients’ Medicaid prescription usage because the program administrators were not authorized to review the Oklahoma Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) data, a barrier which remains. Even though dispensers of controlled substances are required to report details of the transaction to the PDMP within 5 minutes, it does not change prescribing when a practitioner is not routinely checking the PDMP (Citation8,Citation9).

Prior authorization programs

Several prior authorizations (PA) of single opioid prescription products were implemented (, Identifiers C, I, and K). The PA process for MOK typically consists of manual requests initiated by the physician or pharmacy for the prescribed product after the prescription claim is denied at point-of-sale (POS). Individual products included were tramadol extended-release (C), buprenorphine (I), and generic oxymorphone extended-release (K).

Step therapy programs

Step therapy programs are PA programs which MOK utilizes for entire classes of medications. These programs require the use of products designated as first step before use of second or third step products. An example is requiring use of immediate-release generic opioid medications in opioid-naïve patients before moving to extended-release products. Step therapy programs can use manual or automated (computer generated) approvals for products placed on “higher” steps. Step therapy was implemented on the entire class of opioid prescription products in July 2008 (, Identifier E). The intent of this step therapy was increased use of short-term immediate release products for acute pain situations and breakthrough therapy for chronic pain situations and reserving long-acting opioids for opioid tolerant patients. Preferred long-acting generic products were established as the second step before patients were allowed to move to the third step of non-preferred long-acting brand products. Preferred and non-preferred short-acting categories were also established. This policy resulted in a reduction in utilization of second and third step products (Citation10); however, research was not performed to measure other possible outcomes such as an increase in overall short-acting use over preferred long-acting products.

Prospective drug utilization review

MOK first used Prospective DUR POS programming in 2007 to limit prescriptions for hydrocodone to one claim per day supply, thus allowing a patient to have only one prescription for a hydrocodone containing product at a time (, Identifier D). In 2009, MOK implemented a second Prospective DUR ingredient duplication which examines prescription claims as they are submitted for hydrocodone-containing products and reviews each patient’s medication profile to determine if hydrocodone products from previous prescription claims are still available to the patient (, Identifier F). If a duplication of hydrocodone is found, then the new claim rejects at POS and an override is required for claim payment. This POS programming resulted in approximately 70 000 denied claims in the first year (Citation11). However, it is unknown if pharmacies dispensed these products to the patients as cash transactions.

Limit on number of prescriptions

An additional POS programming method was implemented based on the number of hydrocodone prescriptions filled during a 360-day period (, Identifier H). This programming limits patients to 13 prescriptions per year unless authorization is granted and resulted in just over 28 000 denied prescription claims for hydrocodone the first reporting year after implementation (Citation12). Again, it is not known whether patients received the prescriptions on a cash basis from the dispensing pharmacies.

Preferred brand prior authorization

Recently a preferred brand PA was initiated for the new abuse-deterrent formulation of oxymorphone extended-release (, Identifier K). Abuse-deterrent products are formulated to decrease the likelihood of abuse by targeting known or potential routes for each specific product. This PA restricts lower-cost generic versions of the original brand product and allows only use of the new abuse-deterrent brand. There has not been sufficient time to determine if this policy will result in decreased misuse of oxymorphone in the MOK population.

Age restrictions

A final POS programming method was implemented on opioid products based on the patient’s age (, Identifier L). These age restrictions were placed on products containing hydrocodone and allow the liquid formulations for use by children and the solid oral products for use by adolescents and adults. The objective of this policy was to limit the more costly liquid formulations to the most appropriate age group. Exceptions are allowed for members with physical disabilities who require non-solid dosage forms.

Prescriber contract requirement

Previously, prescriptions written by any licensed prescriber could be covered by the MOK pharmacy benefit. However, as part of compliance with the Affordable Care Act (ACA), in 2011, MOK restricted payment of pharmacy claims to those written by prescribers contracted to serve MOK members(, Identifier J). The rationale for the contract requirement was based on patterns noticed by states and CMS of narcotic utilization by members with prescriptions written by non-contracted prescribers. If the prescriber was not contracted and thus not being paid by the Medicaid agencies for office visits, they must have been charging patients directly for services. Additionally, prescribers were under no obligation to comply with agency policy or submit patient records upon request.

Discussion

Oklahoma was in the highest category of state prescription drug overdose age-adjusted death rates in 2008 (15.8 per 100 000 compared to the national average of 11.9 per 100 000) (Citation13). Faced with the significant issue of opioid abuse in the state, policymakers through MOK have attempted to curb misuse by implementing various policies over time within the pharmacy benefit. The number of different policies enacted by MOK reflects efforts to curtail misuse and abuse without interference where high utilization of opioid products may be medically appropriate. Although it is not within the scope of this report to determine if these efforts had an overall effect on the state, it is interesting to highlight some changes in mortality rates in Oklahoma. According to a report in 2013 by the Oklahoma Department of Health, unintentional poisoning mortality rates for Oklahoma increased significantly over the US average from 1999–2010. Oklahoma also saw an increase in the number of prescribed opioids during this time period and prescription opioids remained the most common product listed in unintentional poisoning deaths. And although mortality rates increased for all ages over the entire time period reported, it can be noted that there was an increase from 16.0 in 2007 to 17.7 in 2009 but a subsequent decrease in the rate to 17.2 by 2011. Likewise, there was a decrease in the number of deaths attributed to prescription drugs from 2009–2011 (Citation14). Unfortunately while heroin appears to be an increasing issue of concern nationally (Citation15), Oklahoma currently is not able to clearly distinguish heroin deaths from other morphine-related deaths and it is unclear whether heroin use is replacing prescription opioid use in Oklahoma as it is in other areas of the US.

MOK, in conjunction with its DUR Board, believes that misuse and abuse of these substances is an important societal issue and should be confronted at all intersections of the lives of these individuals, not just at an insurer level. Reaching patients before misuse and abuse occurs is vital. However, MOK has implemented and continues to implement policies which are intended to limit potential misuse and abuse while providing good stewardship of resources and maintaining positive health outcomes.

Programmatic implications of policy changes

For MOK, basic restrictions such as quantity limits, number of prescriptions, and limits based on age, may be most effective in terms of reducing numbers of paid prescription claims for products. While these restrictions are not difficult to implement, maintain, and operate, they do result in additional questions to call centers and higher PA or claim override volumes. These restrictions also place a higher burden on physicians and pharmacies if they wish to move forward with payment of the prescription claim by MOK. An additional limitation of these programs occurs when the dispensing pharmacy simply instructs the patient that the prescription is not covered by MOK and does not attempt to receive reimbursement by MOK for potentially legitimate claims. The result is patients not receiving necessary prescriptions or patients paying out-of-pocket for appropriate opioid prescriptions. PAs and step therapy programs are more complicated to implement and maintain, with step therapy being the most difficult to continually monitor. They also generate higher numbers of phone calls and PA requests. For instance, when the step therapy program was implemented, the number of prior authorizations for opioid products increased from approximately 100 requests monthly to 400 requests monthly. The current average number of requests for this category for all reasons is 650 per month. Based on a recent analysis of OHCA’s prior authorization program, the cost for each PA in Oklahoma is $12.50 (lower than the national benchmark) (Citation16). If implemented today, the step therapy program would have cost the state an additional $3750 per month. A simple PA on a single product such as buprenorphine typically requires a manual review and approval for all initial prescription requests. Products which are placed in step therapy typically have automated pathways which are processed at POS by the claims processing software. Of these two methods, the manual PA process typically results in the highest reduction in approved prescription claims due to the review by clinical pharmacists. Automated approvals are limited to more explicit criteria and do not allow for clinical judgment.

Outcome evidence from policy implementation

Some first efforts at curbing misuse in the Medicaid system were the Lock-In programs. As early as 1977, Singleton published a review of the effects of state Lock-In programs, reporting that the Missouri Medicaid Lock-In program may have reduced the 1976 state Medicaid budget by 1.7% (or $1.8 million) (Citation5). The Hawaii Medicaid Lock-In program estimated a total of $909 992 in saving for 1983 (Citation4). And a review by Blake in 1999 of the Louisiana Medicaid Lock-In program showed reductions in multiple pharmacies, poly-pharmacy, opioid analgesics and overall pharmacy expenditures (Citation6).

Lock-In programs have appeared once again on the national radar. In August 2012, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) convened an expert panel to discuss “Medicaid Patient Review and Restriction (PRR)” (or Lock-In) programs. The final report issued after this panel meeting concluded that PRRs are important programs to reduce accidental deaths, particularly for Medicaid patients (Citation17). In December 2012, researchers at the University of California, Davis prepared a report for the CDC which evaluated the cost and health impacts of PRR programs. A tool was developed that simulated patterns of opioid use and evaluated the results of different restriction policies on health outcomes and costs. The goal is to allow state policy makers to improve their decision making using evidence-based information and allow specific state reviews of current or proposed PRR programs (Citation19).

Finally, the preferred brand PA is a new area for consideration. Medicaid programs may achieve lower net costs for brand name drugs than generics when one of the following situations occurs:

Brand product has a high federally mandated rebate which renders the net cost below that of the generic; or

Brand product has a sufficient supplemental rebate from the drug manufacturer paid directly to the state which renders the net product cost below that of the generic.

As previously mentioned under Lock-In programs, MOK under current state law does not have the legal authority to examine and review the PDMP data. Only providers of care (prescribers and pharmacies) and law enforcement officials have access to PDMP data. This creates a significant hindrance in attempts to evaluate programmatic initiatives to impact abuse and misuse outside of MOK financial responsibility for these prescriptions. From a public health perspective, the goal of program initiatives is to improve the health of plan members by decreasing or eliminating opioid abuse, not to just avoid financial responsibility for abuse. Access to the PDMP would allow MOK and other payers to coordinate monitoring and treatment activities with prescribers and pharmacies even when patients elected to pay cash and avoid plan oversight.

displays the opioid prescription claims per utilizer per month (PUPM) from January 2003 through June 2013. PUPM is a measure based on the number of enrollees who utilize the benefit; this number is a subset of the entire enrolled population. Several events affected the total population of MOK during the time period, including carve-in of a managed care program (January 2004) and carve-out of dually eligible Medicare beneficiaries as a result of Medicare Part D (January 2006). However, by reviewing the claim PUPM for opioids, the effect of the changes in the overall utilizer base is reduced. Upon review, the most noticeable change in the trend is the drop in claims PUPM after the step therapy program was initiated in July 2008.

While not all of the policies MOK implemented over the years were evaluated either for safety and effectiveness or for cost savings, several were. The Prospective DUR duplication of hydrocodone-containing products was estimated to have an annualized cost avoidance of $325 755 (2010 US$) (Citation11). The hydrocodone annual prescription limit was estimated to have an annualized cost avoidance of $83 823 (2011 US$) (Citation12). Overall, the Lock-In program was estimated to have an annual cost reduction of $606 (2006 US$) per locked-in member per month (Citation7). Finally, the restriction of prescribers to those contracted with OHCA, resulted in a decrease of 6% in overall opioid prescription claims (Citation19).

Efforts at limiting misuse and abuse of opioid prescriptions are necessary regardless of payer type. Not only do misuse and abuse of opioid prescriptions contribute to rising healthcare costs, but unchecked misuse and abuse will ultimately lead to addiction for the patient, and/or to fraud on the part of the patient and possibly the provider. Currently MOK is planning to review more of its policies for opioid prescription misuse and abuse. It is hoped that the policy preferring the abuse-deterrent formulation will result in a slower uptake of the generic product by those seeking to misuse it. Although the step therapy program shifted market share from the highest tier to the lower tiers, concern remains over whether this program may have increased use of short-acting opioid products.

According to CMS, opioid abuse and diversion is a leading problem faced by all state Medicaid programs (Citation1). In a study done in Kentucky by Manchikanti et al. on 400 patients treated at a pain management clinic, when compared to commercial insurance, Medicare only, and Medicare and Medicaid (dually eligible), those in the Medicaid-only group had the highest percentage of patients with illicit drug use (39%). Additionally, the Medicaid-only group had the highest combined rate of both illicit drug use and inappropriate use of prescription drugs (60%) (Citation20). CMS partners with the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) and state agencies to promote appropriate use of opioid prescriptions. A law enacted in October 2008 established a “tamper-resistant” prescription paper policy for all non-electronic prescriptions written for Medicaid outpatient drugs. Further, the ACA includes additional measures which can be used to combat abuse. These new measures are: “establish enhanced oversight for new providers, establish periods of enrollment moratoria or other limits on providers identified as being high risk for fraud and abuse, establish enhanced provider screening, and require states to suspend payment when there is a credible allegation of fraud which may include evidence of overprescribing by doctors, overutilization by recipients, or questionable medical necessity” (Citation1). CMS also promotes measures which states can incorporate to detect abuse: using retrospective DUR processes to identify potential patterns of abuse, improving prospective DUR screenings at POS for high opioid doses or potential overuse, reviewing prescriptions written at pain management clinics, searching for fraud across programs, forming collaborative workgroups with other state agencies and neighboring states, using PDMPs, developing new or enhanced Medicaid patient Lock-In programs, promoting the national “Take-Back” campaign, and encouraging both providers and patients to take appropriate steps to safeguard their identities (Citation1).

Recommendations

Any payer contemplating actions similar to MOK should carefully consider the potential for increased work load to their current staff and the overall healthcare system when planning their policies. In general, each of the policies implemented by MOK achieved the desired result in the short term. It is the experience of these policymakers that as one product or sub-category is identified and acted upon, another quickly takes its place. Therefore it is not enough to simply implement a policy and consider this complicated problem solved. Simultaneous implementation of multiple policies may have a higher initial effect on opioid utilization; however, as with most policies, these effects may be greatest in the shortterm. And while policies may seem to meet short-term goals, review of the outcomes for unintended clinical consequences should also occur (Citation21).

The current epidemic should be addressed on the patient level in areas unrelated to prescription utilization. Payers should ensure that addiction treatment and counseling services are readily available and affordable. Nationally, programs should continue encouraging people to seek help or encouraging family members to seek help for loved ones. Most people do not plan to become physically and psychologically addicted to prescription pain medications and should not face stigma when seeking treatment.

Payers should address the provider side of this epidemic. Analysis of physician prescribing patterns is necessary to control misuse and abuse of opioid prescription drugs. When prescribing patterns are reviewed in combination with a thorough physician peer quality panel assessment, a higher impact on prescribing may be possible. State boards of medical licensure must become more active in monitoring narcotic prescribing patterns and in providing assistance as well as disciplinary measures when needed. Information provided by payers should be used by physicians to review and revise their prescribing habits, and not assumed to be punitive or invasive. Only by working together can we prevent serious problems before they arise.

Regardless of the nature of policies for deterring misuse and abuse of opioid prescription drugs, it is imperative that these efforts continue and results from these policies be shared across payer types. To that end, the CDC and the National Institutes of Health – National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIH-NIDA) are currently funding research to determine the impact of policies such as those outlined above on inappropriate prescribing of opioids (Citation22).

Conclusions

Despite multiple efforts currently in effect for the pharmacy benefit, misuse and abuse of prescription opioids continues. As health plans, regulatory agencies, and law enforcement officials introduce more complex countermeasures, a thorough review of new policies should be performed to determine their effectiveness so others may adopt successful policies and avoid poor or overly expensive options. With new abuse-deterrent formulations for long-acting products coming to market, real-world evaluations are needed to determine whether these products effectively reduce misuse, or simply divert users to other drugs of abuse. Only by continued combined effort to treat not only abuse, but also to intervene before more devastating consequences occur, can we begin to conquer this serious social problem which touches us all.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

References

- Drug Diversion in the Medicaid Program State Strategies for Reducing Prescription Drug Diversion in Medicaid. In: Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2012

- Katz NP, Birnbaum H, Brennen MJ, Freedman JD, Gilmore GP, Jay D, Kenna GA, et al. Prescription opioid abuse: challenges and opportunities for payers. Am J Managed Care 2013;19:295–302

- McAdam-Marx C, Roland CL, Cleveland J, Oderda GM. Costs of opioid abuse and misuse determined from a Medicaid database. J Pain Palliative Care Pharmacother 2010;24:5–18

- Chinn FJ. Medicaid recipient lock-in program – Hawaii’s experience in six years. Hawaii Med J 1985;44:9–18

- Singleton TE. Missouri’s Lock-In:control of recipient misutilization. J Medicaid Manage 1977;1:10–17

- Blake S. The effect of the Louisiana Medicaid lock-in on prescription drug utilization and expenditures. Drug Benefit Trends 1999;11:45–55

- Keast SL. Lock-In program evaluation. Oklahoma City, OK: Oklahoma Health Care Authority; 2008

- Prescription Monitoring Program (PMP). Oklahoma Bureau of Narcotis and Dangerous Drugs Control. Available from: http://www.ok.gov/obndd/Prescription_Monitoring_Program/. [last accessed 25 Feb 2014]

- Oklahoma State Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs Control. In: Rules OSOoA, ed. 475:45-1-5. Oklahoma; 2011

- Annual Review of Narcotic Analgesics – Fiscal Year 2009: Oklahoma Health Care Authority; 2009

- Oklahoma Medicaid Drug Utilization Review Annual Report – Federal Fiscal Year 2010: Okahoma Health Care Authority; 2011

- Oklahoma Medicaid Drug Utilization Review Annual Report – Federal Fiscal Year 2011: Oklahoma Health Care Authority; 2012

- Policy impact: prescription drug overdose state rates; Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/HomeandRecreationalSafety/rxbrief/states.html [last accessed 15 Aug 2013]

- Nguyen C, Wendling T, Brown S. Unintentional poisoning deaths in Oklahoma, 2007–2011. Oklahoma City, OK: Injury Prevention Service Oklahoma State Department of Health; 2013

- Massatti R, Beeghly C, Hall O, Kariisa M, Potts L. Increasing heroin overdoses in Ohio: understanding the issue. Columbus, OH: Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services; 2014

- Independent Review of the SoonerCare Pharmacy Benefit and Management. Oklahoma City, OK: Mercer Health and Benefits LLC; 14 April 2014

- CDC Expert Panel Meeting Report. Patient Review and Restriction Programs Lessons learned from state Medicaid programs: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) December 9, 2013

- Melnikow J, Yang Z, Soulsby M, Ritley D, Kizer K. Approaches to Drug Overdose Prevention Analytical Tool (ADOPT): evaluating cost and health impacts of a Medicaid Patient Review & Restriction Program: Center for Healthcare Policy and Research; Dec 2012

- Oklahoma Health Care Authority. Internal Report: Utilization Review of Narcotic Prescribing. 2012

- Manchikanti L, Fellows B, Damron KS, Pampati V, McManus CD. Prevalence of illicit drug use among individuals with chronic pain in the Commonwealth of Kentucky: an evaluation of patterns and trends. J Kentucky Med Assoc 2005;103:55–62

- Soumerai SB. Benefits and risks of increasing restrictions on access to costly drugs in Medicaid. Health Affairs 2004;23:135–146

- RFA-CE-14-002 Research to prevent prescription drug overdoses. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – Department of Health and Human Services. Available from:http://www.grants.gov/web/grants/view-opportunity.html?oppId=249388 [last accessed 27 Feb 2014]