Clinical governance is hot. In the last few years, numerous alarming articles have been published about the need for real accountability for the safe and client-centered delivery of health services. In reaction to this call, Clinical governance has been put forward as a possibly realistic answer.

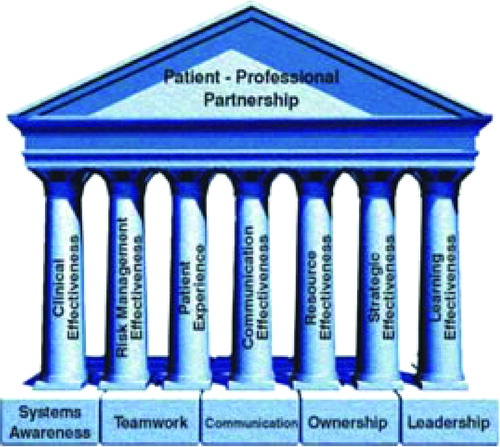

As always happens when a concept flourishes, different definitions evolve, each slightly different than the other. Scally and Donaldson [Citation1], for example, define Clinical governance as ‘the system through which healthcare organisations are accountable for continuously improving the quality of their services and safeguarding high standards of care, by creating an environment in which clinical excellence will flourish’. The Australian Council on Healthcare Standards speaks of ‘the system by which the governing body, managers and clinicians share responsibility and are held accountable for patient care, minimising risks to consumers and for continuously monitoring and improving the quality of clinical care’ [Citation2]. If we step beyond the details, it becomes clear that CG shares the same ideological roots as psychosomatic medicine: the striving for integrated care and a system theoretical view on patients (micro level) as well as on health care organizations (macro level). From this perspective there is a need for corresponding and complementary competences on individual and organizational levels. Essential elements in this are the awareness to be part of a larger (health care) system, communication, teamwork, leadership, and ownership [Citation4] as shown in .

More important than the precise definitions, are the consequences of this cultural (r)evolution. Where some emphasize the gains in terms of safety and accountability, others fear the growth in terms of bureaucracy, loss of effectiveness, and professional autonomy. In order to induce the first and to reduce the last, it seems important that CG is not blindly followed as the new ideology. In order to contribute to health care, CG should be consciously introduced. Medical professionals must learn that CG depends heavily on their knowledge, their competence in medical management, their leadership qualities and especially on their participation in the process of governance. Since these qualities and ambitions are not present in every clinician per se, sound educational programs on personal leadership and medical management should be made available. What can be expected in the next decade is an enormous need for educational activities in domains like teamwork and communication, not as isolated activities but as integrated clinical competencies. And this is where psychosomatically oriented clinicians make their entry. As no other professionals in health care they are able to combine educational and clinical expertise with themes like teamwork and communication. It is therefore this unique combination which makes it possible to go one step beyond the positive results of current projects focussing on improving patient care. Off course, lessons have to be learned from errors and even by working within the governing variables important adaptations could be made. This what Argyris and Schön called ‘single loop learning’. However, important adaptations could be made. However, if we are able to question governing variables themselves, so called ‘double-loop learning’ could be achieved with even better results. This requires for health care to be regarded as an integral system, focussing not solely on patients, but establishing a focus which includes clinical colleagues, managers, directors, and decision makers. Together they can be target groups for educational intervention. As we already know from our psychosomatic experiences, only broad support will carry improvements and if stability is required, improvements should be adopted by others in order for them to have a chance at being generalized to other domains of health care.

At the end of the first decade of the new millennium, the future is looking bright for psychosomatic medicine. Plenty of opportunities for everyone. To quote Bob Hope: I have always been in the right place, at the right time. Of course, I did have to steer myself there! …

References

- Scally G, Donaldson LJ. Clinical governance and the drive for quality improvement in the new NHS in England. BMJ 1998;317:61–65.

- Victorian Quality Council. Developing the clinical leadership role in clinical governance. A guide for clinicians and health servicesNotting Hill: Victoria Quality Council; 2005.

- Argyris C, Schön D. Theory in practice: increasing professional effectiveness. San Francisco: Jossey Bass; 1974.

- Niccols S, Cullen R, O'Neill S, Halligan A. Clinical governance: its origins and its foundations. Br J Clin Govern 2000;5:172–178.