Abstract

Objective. To explore views and attitudes among general practitioners (GPs) and researchers in the field of general practice towards problems and challenges related to treatment of patients with multimorbidity. Setting. A workshop entitled Patients with multimorbidity in general practice held during the Nordic Congress of General Practice in Tampere, Finland, 2013. Subjects. A total of 180 GPs and researchers. Design. Data for this summary report originate from audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim plenary discussions as well as 76 short questionnaires answered by attendees during the workshop. The data were analysed using framework analysis. Results. (i) Complex care pathways and clinical guidelines developed for single diseases were identified as very challenging when handling patients with multimorbidity; (ii) insufficient cooperation between the professionals involved in the care of multimorbid patients underlined the GPs’ impression of a fragmented health care system; (iii) GPs found it challenging to establish a good dialogue and prioritize problems with patients within the timeframe of a normal consultation; (iv) the future role of the GP was discussed in relation to diminishing health inequality, and current payment systems were criticized for not matching the treatment patterns of patients with multimorbidity. Conclusion. The participants supported the development of a future research strategy to improve the treatment of patients with multimorbidity. Four main areas were identified, which need to be investigated further to improve care for this steadily growing patient group.

The prevalence of multimorbidity is high and rising, including in the Nordic countries. Although care of patients with multimorbidity has been a fundamental task in general practice for many years, more research is needed to facilitate and guide quality development.

GPs found it challenging to prioritize patients’ medical and personal needs in the short timeframe of the consultation.

GPs debated their future role in the effort to diminish health inequality in relation to multimorbidity.

GPs expressed feelings of insufficiency with reference to the general lack of knowledge regarding best practice for multimorbid patients.

Introduction

The number of people living with multiple chronic diseases, multimorbidity, is high and rising, also in the Nordic countries [Citation1–3]. Patients with multimorbidity often need frequent general practice consultations, complex and structured care, as well as coordination between health and social sectors [Citation4]. General practitioners (GPs) report a heavier workload burden and greater time consumption, especially when somatic and psychological chronic conditions are combined [Citation5]. The prevalence of multimorbidity varies between 3.5% and 98.5% in primary care depending on the definition of multimorbidity [Citation1].

Solutions to multiple problems in complex situations profit from a generalist approach to care [Citation6,Citation7]. Although care of patients with multimorbidity has been a fundamental task in general practice for many years, more research is needed to facilitate and guide the quality development.

At the Nordic Congress of General Practice in Tampere in 2013, we organized a workshop with this specific focus. By bringing together general practitioners and researchers from the Nordic countries, our aim was to explore the participants’ views and attitudes toward problems and challenges related to treatment of patients with multimorbidity in general practice.

Material and methods

The workshop was open to all congress participants and was organized in collaboration between Nordic general practice research institutions. In total 180 people attended, of whom the majority were GPs.

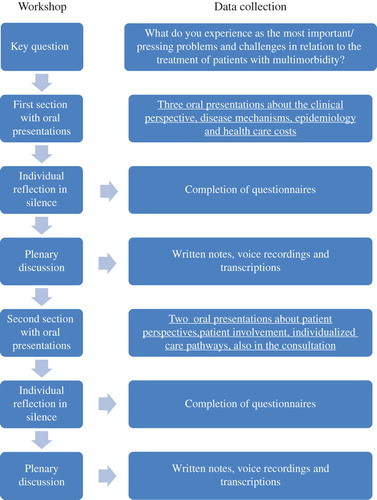

The overall focus of the workshop derived from both clinical experience and literature review, and was expressed in the key question: “What do you experience as the most important/pressing problems and challenges in relation to the treatment of patients with multimorbidity?” To address this question we divided the workshop into two sections. The first section focused on clinical perspective, epidemiology, and economy, while the second section concentrated on organization, coordination, and the consultation. To establish optimal conditions for an ongoing discussion of the main question, each section consisted of short oral presentations, then silent individual reflection, followed by plenary discussion. The intention of our workshop structure was to provide listeners with inspirational inputs to stimulate their own thoughts on the subject, thereby ensuring that the plenary discussions were based on actual experiences from the audience's everyday life in general practice. Preliminary conclusions from the plenary discussions were simultaneously captured and summarized through laptop and screen by a rapporteur.

All participants were invited to complete short, open-ended questionnaires with their reflections and thoughts on the themes of the workshop in relation to the key question (see web appendix). Of the 180 participants, 76 (42%) filled in the questionnaire and 69 of them provided information on their professional background. Of these, 62 (90%) were GPs or GP trainees. The material for our analysis consisted of the short questionnaires, recorded and transcribed plenary discussions, and notes, which were taken by two rapporteurs during the discussions ().

We applied framework analysis (FA) to analyse the material. FA has five stages: familiarization; identification of thematic framework; indexing; charting, and finally mapping and interpretation [Citation8,Citation9]. We read the transcripts of recordings of the plenary discussions repeatedly to familiarize ourselves with the data and also the answers to the open-ended questionnaire. Recurrent themes and a thematic framework were identified based on the headings of the workshop and on emerging themes. Finally, we indexed our data and charted them into four themes in accordance with the framework. We carried out further analysis of each theme to cover the range and association of phenomena. FA was originally developed as a pragmatic approach for applied policy research [Citation10]. It is recommended to use FA when the data collection is more structured than in most qualitative research and when the objectives of the investigation are set in advance and shaped by specific information needs, as in our study [Citation8]. In FA the analytic categories can be used deductively as well as developed inductively. We included themes of the presentations at the workshops as analytic categories because participants’ answers were reflections on the presentations.

Results

The following four themes emerged as particularly important or challenging in relation to the treatment of patients with multimorbidity. The themes are listed in no particular order ().

A. Complex care and clinical guidelines

I see it as a problem in my daily life that, um, the multimorbidity patient, um, fits into a lot of guidelines. And sometimes they could work together, but other times, what is good for one of the gold standards is bad for the other. And I need a tool for, together with the patient, to prioritize which [disease] is the most important. (GP, Denmark)

GPs found it challenging to oversee several types of medicines and treatments, as well as their side effects and interactions, when treating patients with multimorbidity. Clinical guidelines often focus on single diseases and lead to polypharmacy, with potential risks of adverse drug events and compliance problems. The participants pointed out that the established practice of excluding patients with multimorbidity from medical trials produces a genuine lack of clinical evidence concerning the treatment and management of the multimorbid patient.

B. Insufficient cooperation and fragmented health care

… if the heart disease doctor says that's really important for you, um, and the other doctor from another disease [specialty] says, well, that's important and there's no, um, connection, [then] they're not going in the same direction, then the patient comes to me with all the frustrations…. (GP, Denmark)

Both inter- and cross-sectorial collaboration was described as problematic by the participants, leading to a greater workload for the GP. Inefficient or absent communication were identified as an obstacle to providing the best possible support for patients across specialties and sectors as well as causing unnecessary repetition of examinations and tests. The reasons given for this unsatisfactory situation varied but included practical hindrances, such as incompatible IT systems between care agencies, or the logistical challenges of working at different locations. Participants also addressed issues such as lack of acknowledgement among the cooperating professionals, especially from the secondary care sector towards the primary care sector. Inter-professional disagreement on how to organize optimal management of patients with multimorbidity was raised as a complicating factor for collaboration. GPs suggested that, to some extent, general dissatisfaction with cross-sectoral collaboration was a result of the different sectors having different focus areas. Specialists were seen as colleagues focusing on one specific problem, whereas the GPs considered themselves to be more concerned with the whole patient and all of their problems.

C. Difficulties with dialogue and prioritization in the consultation

I [need to] get a better complete idea about the background, that is, what's the priority of this old lady, what's the priority of this man…. [If] I get a better idea [of the background] this will solve many problems. (GP, Finland)

GPs experienced prioritizing between the different coexisting diseases as a problematic part of the consultation, especially when the patient suffered from both somatic and mental disorders. While patient involvement was anticipated and recognized as important, it was described as difficult to assess and implement in practice. GPs recognized that psychosocial factors, previous experiences, and the patients’ expectations affected the patients’ prioritizations and needs. In situations where these conditions were unknown, GPs found it very difficult to ascertain which direction to follow, and with what final goal they should prioritize among the different diseases. The lack of time was emphasized as a significant issue affecting how the GP approached both prioritization of disease and patient involvement.

D. Role of the general practitioner and unadapted payment systems

If multimorbidity is a socioeconomic and lifestyle condition how can doctors [then] influence the community? How can we increase education in our community? How can we influence better conditions for young children and families? (GP, Iceland)

If it is accepted that multimorbidity is strongly influenced by the socioeconomic conditions and lifestyle of the patient, GPs debated how much they actually could and should do. There was scepticism in discussions concerning what the most important tasks of the GP are. The GP's role as gatekeeper to the rest of the health care system was questioned by participants with reference to the lack of existing knowledge concerning the optimal care pathway for multimorbid patients. This complicated referral decisions. Finally, there was an apparent clash between how an average consultation with a multimorbid patient proceeds, and the way the payment system is structured in some of the countries represented. Due to the multiplicity of health challenges, multimorbid patients often present several problems at a time, which makes them fit very poorly within a consultation format, where a fixed amount of time is allocated to address one specific problem.

Discussion

Participants from all Nordic countries recognized problems concerning the treatment of patients with multimorbidity and they described the management of these patients as demanding. Prioritizing care, while dealing with clinical uncertainty, medical complexity, and inappropriate guidelines during a short consultation, was highlighted as very problematic. Particular risks were identified as the unintended side effects of polypharmacy, and a very complicated dialogue-based assessment and agreement of treatment goals with the patient. Furthermore, lack of communication and mutual appreciation between health and social sectors was emphasized as a central issue causing sub-optimal collaboration between professional parties.

Some of our results concur with the findings of previous research. Studies have shown that GPs experience a heavier workload and greater time pressures when treating multimorbid patients [Citation5,Citation11]. Working with multimorbidity, especially in deprived areas, can be exhausting and GPs have experienced it as “soul destroying” [Citation12]. Similarly, the feelings of GPs in our study, that they lacked competence and experienced difficulties in meeting patients’ needs, are factors which have also been reported previously [Citation11]. Some researchers have highlighted patient complexity and polypharmacy as important reasons for GPs’ increased workload [Citation13]. In line with discussions regarding the importance of knowing the patient's background, ongoing research projects are working on a more comprehensive definition of multimorbidity, which includes bio-psychosocial factors [Citation14].

However, three themes emerged during the plenary discussions in Tampere that, to our knowledge, have not previously been reported. The first new theme was whether or not it is a relevant task for GPs to proactively address inequities in health. Patients from socioeconomically deprived areas develop multimorbidity a decade before people in affluent areas [Citation15], and the risk of developing multimorbidity in later life is affected by deprivation in childhood or even before conception [Citation16]. These factors make the question of health inequality more wide-ranging than something that can be solved solely in primary care.

The second theme related to what the GP can and should do for patients with multimorbidity. This theme addressed how GPs should cope with feelings of insufficiency and of not being able to do enough for patients in the light of existing resources.

The third theme addressed the GP's role as gatekeeper to the rest of the health care system. This was questioned by participants with reference to the existing knowledge gaps and lack of overview when it comes to optimal care pathways for multimorbid patients. GPs expressed their feelings of uncertainty concerning how to make the best referrals (17).

Some key issues in the published discourse on multimorbidity were not generally highlighted at our workshop. Problems with discontinuing medication have previously been raised as an important issue [Citation18]. This theme was not pinpointed in the discussion or questionnaires. Another question that is common in current literature deals with what we want to achieve with treatment. Measures of multimorbidity increasingly include a focus on how disorders are experienced by patients, rather than the diagnosed number of diseases [Citation19]. Quality of life and treatment of symptoms then become the main aim, rather than causal treatment [Citation20]. This shift of focus was not addressed by the participants in our study.

Our workshop's overarching question specifically addressed problems and challenges, as opposed to, for example, strengths and solutions. This way of phrasing the question might have influenced the attitudes of participants toward the subject in a more negative direction than would otherwise have been the case. Also, the themes of the short oral presentations might have affected the directions of the succeeding plenum discussions. Furthermore, our participants represent a group of engaged and research-orientated GPs. This might not be representative of all GPs, which may have affected the results. However, the Nordic Congress included many clinically active GPs, thus embedding the results in everyday clinical practice.

Conclusion

Findings from the workshop point at four areas that were experienced as especially problematic and challenging for GPs when treating patients with multimorbidity. These were: medical complexity; insufficient cooperation; difficult prioritization and patient dialogue; and doubts regarding the GP's role (see ).

The participants moreover felt that their efforts to provide high-quality care to this group of patients were insufficient. This reflects a need for greater sharing of the tasks of managing multimorbidity with others, e.g. geriatricians, and signals a new focus on where we can cooperate with the educational and social systems to diminish inequities in health. Our study highlights a need for better education and communication skills as a prerequisite for GPs to handle multimorbidity.

Acknowledgement

Mogens Vestergaard is supported by an unrestricted grant from the Lundbeck Foundation.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Fortin M, Stewart M, Poitras ME, Almirall J, Maddocks H. A systematic review of prevalence studies on multimorbidity: toward a more uniform methodology. Ann Fam Med 2012;10:142–51.

- Uijen AA, van de Lisdonk EH. Multimorbidity in primary care: Prevalence and trend over the last 20 years. Eur J Gen Pract 2008;14(Suppl 1):28–32.

- Tomasdottir MOT, Getz L, Sigurdsson JA, Petursson H, Kirkengen AL, Krokstad S, McEwen B, Hetlevik I. Co- and multimorbidity patterns in an unselected Norwegian population: Cross-sectional analysis based on the HUNT Study and theoretical reflections concerning basic medical models. Eur J for Person Centered Healthcare 2013;2:335–45.

- Salisbury C, Johnson L, Purdy S, Valderas JM, Montgomery AA. Epidemiology and impact of multimorbidity in primary care: A retrospective cohort study. Br J Gen Pract 2011;61:e12–e21.

- Moth G, Vestergaard M, Vedsted P. Chronic care management in Danish general practice: A cross-sectional study of workload and multimorbidity. BMC Fam Pract 2012; 13:52.

- Stange KC. The generalist approach. Ann Fam Med 2009;7:198–203.

- Mercer SW, Gunn J, Bower P, Wyke S, Guthrie B. Managing patients with mental and physical multimorbidity. BMJ 2012;345:e5559.

- Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care: Analysing qualitative data. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2000;320:114–16.

- Ritchie J, Spencer L, W OC. Carrying out qualitative analysis. In: Ritchie J, Lewis J, editors. Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. London: Sage Publication; 2003. p 219–62.

- Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A, Burgess RG, editors. Analysing qualitative data. London: Routledge; 1994. p 172–94.

- Smith SM, O’Kelly S, O’Dowd T. GPs’ and pharmacists’ experiences of managing multimorbidity: A ‘Pandora's box’. Br J Gen Pract 2010;60:e285–e94.

- O’Brien R, Wyke S, Guthrie B, Watt G, Mercer S. An ‘endless struggle’: A qualitative study of general practitioners’ and practice nurses’ experiences of managing multimorbidity in socio-economically deprived areas of Scotland. Chronic Illn 2011;7:45–59.

- Smith SM, Ferede A, O’Dowd T. Multimorbidity in younger deprived patients: An exploratory study of research and service implications in general practice. BMC Fam Pract 2008;9:1–5.

- Le Reste JY, Nabbe P, Manceau B, Lygidakis C, Doerr C, Lingner H, et al. The European General Practice Research Network presents a comprehensive definition of multimorbidity in family medicine and long term care, following a systematic review of relevant literature. J Am Med Directors Assoc 2013;14:319–25.

- Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, Watt G, Wyke S, Guthrie B. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: A cross-sectional study. Lancet 2012;380:37–43.

- Cornish RP, Boyd A, Van ST, Salisbury C, Macleod J. Socio-economic position and childhood multimorbidity: A study using linkage between the Avon longitudinal study of parents and children and the general practice research database. Int J Equity in Health 2013;12:66.

- DuGoff EH, Dy S, Giovannetti ER, Leff B, Boyd CM. Setting standards at the forefront of delivery system reform: Aligning care coordination quality measures for multiple chronic conditions. J Healthcare Quality: official publication of the National Association for Healthcare Quality 2013; 35:58–69.

- Schuling J, Gebben H, Veehof LJ, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM. Deprescribing medication in very elderly patients with multimorbidity: The view of Dutch GPs. A qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract 2012;13:56.

- Bayliss EA, Ellis JL, Steiner JF. Seniors’ self-reported multimorbidity captured biopsychosocial factors not incorporated into two other data-based morbidity measures. J Cln Epidemiol 2009;62:550–7 e1.

- Luijks HD, Loeffen MJ, Lagro-Janssen AL, Van WC, Lucassen PL, Schermer TR. GPs’ considerations in multimorbidity management: A qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract 2012;62:e503–e10.