To the Editor

The development of therapies that selectively target specific molecules needed for tumour development, has introduced a new era in oncology. The intracel-lular Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK protein kinase signal cascade is a key pathway involved in cell proliferation and survival, which can be activated by a number of cell surface receptors, including epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) [Citation1].

Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinases 1 and 2 (MEK1/2) are the central components of this pathway. Inhibition of MEK1/2 has the potential to block inappropriate signal transduction regardless of the upstream oncogenic aberration. Oral AZD6244 is a potent, selective, uncompetitive inhibitor of MEK1/2 by which signal transduction of multiple pathways, including the EGFR pathway, is inhibited. Clinical efficacy has been shown in phase I and II monotherapy studies in patients with advanced cancers [Citation2–4].

AZD6244 is associated with cutaneous adverse events, which are similar to those experienced following targeted treatments that inhibit EGFR [Citation5]. Here we report seven MEK1/2 inhibitor-related dermatological conditions; acneiform eruption, xero-sis cutis, paronychia, exacerbation of psoriasis, anal fissure, hair abnormalities and palmar-plantar eryth-rodysaesthesia (PPE); and their management in three patients treated with AZD6244 in a phase I study [Citation4].

Patient 1

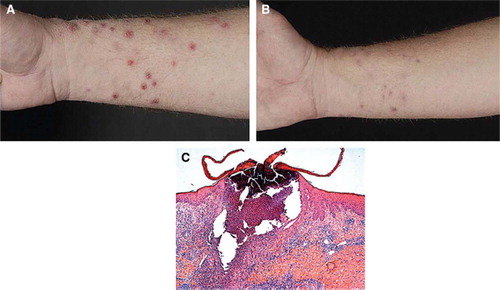

A 56-year-old Caucasian male was diagnosed with an ocular melanoma and synchronous liver metasta-ses in 2007. After failure of dacarbazine, treatment with oral AZD6244 75 mg BID was initiated in November 2007. After eight days of treatment he developed extensive erythematous papules, nodules and pustules on the face, trunk and predominantly on the upper and lower extremities (). Histology of a punch biopsy showed an acanthotic epidermis with diffuse hyperkeratosis, a massive influx of neutrophils and follicle-related perforating pustules (). Brown-Hopps staining showed profound bacterial involvement in the absence of viral inclusions. This acute perforating folliculitis was initially treated with topical erythromycin gel 2%. Since the lesions progressed causing pruritus and pain, we started systemic treatment with minocyclin 100 mg (once daily for six weeks) and topical chlo-rhexidine BID, which resulted in recovery of the lesions within two weeks (). A second cycle of minocyclin was prescribed because of recurrent perforating folliculitis, which resolved after cessation of AZD6244 treatment because of progressive disease (PD) in July 2008.

Figure 1. Patient 1: (A) Severe purulent perforating bacterial folliculitis, with an atypical distribution as compared to the acneiform eruption seen in patients with an EGFR-inhibitor (left panel). (B) Recovery of acneiform eruptions after treatment with oral minocyclin 100 mg once daily (mid panel). (C) Histopathology of one of the lesions, showing an acanthotic epidermis with diffuse hyperkeratosis, a enlarged ruptured follicle with a massive influx of an inflammatory infiltrate mainly consisting of neutrophils. (Magnification 100′)

Patient 2

A 26-year-old Caucasian female presented in 2006 with a relapse of melanoma in the neck region with lymphogenic and chest wall metastases. After failure of dacarbazine, the patient started with AZD6244 75 mg BID in July 2007.

After one week a typical acneiform eruption was diagnosed localised in the face, upper trunk and scalp region. Topical treatment with erythromycin gel 2% and povidone-iodine shampoo resolved the symptoms within two weeks, although some of the facial acneiform eruption persisted. This was accompanied by a severe diffuse xerosis cutis, for which an emollient (cetomacrogol ointment) was used and water contact was avoided.

After two months of treatment with AZD6244, the patient developed recurrent painful paronychia on both her fingers and toes. Some of the paronychia resolved spontaneously and some were treated successfully with silver nitrate, topical steroids and minocyclin 100 mg once daily, respectively. At the same time, the patient developed severe pain, inflam-mation and fissures at all mucocutaneous transition sites: the nose, mouth, eyes, vagina and anus. Rectal examination showed a superficial anal fissure of 4 cm. Withholding treatment with AZD6244 for four days had a beneficial effect, and no dose reduction was applied when treatment was resumed. Finally, eight months after start of AZD6244, discoloured, brittle and curlier scalp hair was observed simultaneously with a mild alopecia.

The patient's melanoma is currently in complete response for over one and a half years and patient rates the cutaneous adverse events of AZD6244 as acceptable. Hence, treatment with AZD6244 is continued without dose reduction despite these extensive dermatological adverse events. Instead, short drug interruptions are applied when necessary.

Patient 3

A 56-year-old Caucasian male with a history of mild plaque-type psoriasis since 2000, was diagnosed with metastatic colorectal cancer. Patient initiated treatment with AZD6244 75 mg BID in July 2007 after failure of all other standard anti-cancer therapies. He developed erythematous papulopustules in the face after two weeks of treatment, which was diagnosed as a facial acneiform eruption. The lesions responded well to topical erythromycin gel 2% BID.

At the start of the study, the patient had a mild and stable plaque-type psoriasis located on the extensor side of both elbows. However, after four weeks of treatment with AZD6244, an exacerbation of psoriasis was observed with marked pruritus. Clinical examination identified a diffuse xerosis cutis with centrifugal expanding, sharply demarcated erythe-matosquamous plaques and many pin-point papules on the arms, legs and scalp, indicating active psoriasis (). The patient did not have a streptococcal throat infection, stressful events or known psoriasis-aggravating medication. An exacerbation of plaque-type psoriasis due to treatment with AZD6244 was hypothesised and topical treatment was started with a combination ointment containing betamethasone valerate 0.05% and calcipotriol 0.005%, once daily, for the body and 10% salicylic acid in desoximeta-sone 0.25% emulsion for the scalp.

Figure 2. Patient 3: Exacerbation of sharply demarcated erythematosquamous plaques and many pin-point psoriatic papules, designated as psoriasis.

Furthermore, patient developed PPE (also known as hand-foot syndrome) two months after the start of AZD6244 treatment. The soles of the feet and palms of the hands were erythematous with fissures, hyperkeratosis and oedema, without nail changes. A bland emollient was prescribed (cetomacrogol ointment). Although treatment resulted in some symptom improvement, both the exacerbation of the psoriasis and PPE did not resolve completely until discontinuation of AZD6244 due to PD after four months of treatment.

Discussion

Treatment with AZD6244 is associated with a dose-dependent erythematous maculopapular rash, occurring in 46–74% of patients [Citation2,Citation4,Citation6]. Resolution typically occurred with AZD6244 dosing interruption and/or dose reduction [Citation2].

AZD6244-associated dermatological conditions are manageable, with minimal need for dose reductions and/or interruptions of therapy. We reported acnei-form eruptions, xerosis cutis, paronychia and hair changes, similar to the adverse events observed with EGFR inhibitors [Citation5]. The pathophysiology of EGFR-related cutaneous adverse events is largely unclear [Citation7]. There is currently no common consensus for the treatment of EGFR inhibitor-related skin rash, although recommendations typically include the use of topical antibiotics for mild skin reactions, and topical antibiotics combined with a systemic tetracy-cline antibiotic for more moderate conditions [Citation7]. In the described cases, topical and systemic antibiotics were mainly used. In a recent study patients with similar MEK1/2 inhibitor-related skin rashes were also successfully treated using antiinflammatory steroids [Citation8]. This treatment strategy should also be considered.

In vitro studies showed encouraging results for the use of EGFR inhibitors and they have been proposed as a potential treatment strategy for psoriasis [Citation9–12]. In contrast with this, exacerbation of psoriasis was observed in patient 3 following treatment with the MEK1/2 inhibitor AZD6244.

In addition to inhibiting EGFR signalling through the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway, AZD6244 can also block vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR). VEGFR inhibition is associated with PPE [Citation13]. PPE consists of symmetric acral erythematous and edematous lesions with desquamation, fissures and hyperkeratosis localised in pressure sores. This was demonstrated by patient 3. Treatment with topical agents having kerolytic, antiproliferative and anti-inflammatory proper ties could be considered as a treatment strategy for MEK1/2 inhibitor-related PPE.

Interestingly, anti-tumour activity has previously been correlated with incidence of acneiform eruptions during treatment with EGFR inhibitors [Citation14]. If MEK1/2 inhibitor-related skin adverse events are predictive for tumour response is not identified, yet. Notwithstanding, early anticipation and recognition of the cutaneous adverse events may improve patient compliance and patient outcomes.

In conclusion, the MEK1/2 inhibitor AZD6244 is a promising novel anti-cancer treatment and associated with manageable dermatological conditions similar to those caused by EGFR inhibitors. Treatment strategies similar to those of EGFR inhibitors may be applied, consisting of short drug interruptions, topical and systemic antibiotics (mainly for their anti-inflammatory properties) and topical anti-inflammatory corticosteroids [Citation2,Citation8,Citation15].

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Sally Humphries, from MediTech Media, who provided editing assistance funded by AstraZen-eca. The patients were participating in a phase I trial sponsored by AstraZeneca. Declaration of interest: Dr. M. Cantarini is an employee of AstraZeneca. All other authors do not declare any conflicts of interest.

References

- Beeram M, Patnaik A, Rowinsky EK. Raf: A strategic target for therapeutic development against cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:6771–90.

- Adjei AA, Cohen RB, Franklin W, Morris C, Wilson D, Molina JR, . Phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacody-namic study of the oral, small-molecule mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1/2 inhibitor AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) in patients with advanced cancers. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:2139–6.

- Dummer R, Robert C, Chapman PB, Sosman JA, Middleton M, Bastholt L, . AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) vs temozolomide (TMZ) in patients (pts) with advanced melanoma: An open-label, randomized, multi-center, phase II study. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:(Abstract)9033.

- Agarwal R, Banergi U, Camidge CR, Brown KH, Cantarini CV, Morris C, . The first-in-human study of the solid oral dosage form of AZD6244 (ARRY-142886): A phase I trial in patients (pts) with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008;26: (Abstract)3535.

- Segaert S, Van Cutsem E. Clinical signs, pathophysiology and management of skin toxicity during therapy with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Ann Oncol 2005;16: 1425–33.

- Sarker D, Banergi U, Agarwal R. Relative oral bioavailability of the hydrogen sulphate (Hyd-sulfate) capsule and free-base suspension formulations of AZD6244 (ARRY-142886): A Phase I trial in patients with advanced cancer. Ann Oncol 2008;19:/viii153–viii165.

- Lacouture ME. Mechanisms of cutaneous toxicities to EGFR inhibitors. Nat Rev Cancer 2006;6:803–12.

- Schad K, Baumann Conzett K, Zipser MC . MEK kinase inhibition (mitogen-activated protein/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase) by AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) results in severe disturbance of epidermal home-ostasis with acute inflammation and chronic maladaptation. 2008 (submitted).

- Ben Bassat H, Klein BY. Inhibitors of tyrosine kinases in the treatment of psoriasis. Curr Pharm Des 2000;6:933–42.

- Wierzbicka E, Tourani JM, Guillet G. Improvement of psoriasis and cutaneous side-effects during tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy for renal metastatic adenocarcinoma. A role for epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors in psoriasis? Br J Dermatol 2006;155:213.

- Varani J, Kang S, Stoll S, Elder JT. Human psoriatic skin in organ culture: Comparison with normal skin exposed to exogenous growth factors and effects of an antibody to the EGF receptor. Pathobiology 1998;66:253–9.

- Powell TJ, Ben Bassat H, Klein BY, Chen H, Shenoy N, McCollough J, . Growth inhibition of psoriatic kerati-nocytes by quinazoline tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Br J Dermatol 1999;141:802–10.

- Autier J, Escudier B, Wechsler, Spatz A, Robert C. Prospective study of the cutaneous adverse effects of sorafenib, a novel multikinase inhibitor. Arch Dermatol 2008;144:886–92.

- Racca P, Fanchini L, Caliendo V, Ritorto G, Evangelista W, Volpatto R, . Efficacy and skin toxicity management with cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer: Outcomes from an oncologic/dermatologic cooperation. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2008;7:48–54.

- Sapadin AN, Fleishmajer R. Tetracyclines: Nonantibiotic properties and their clinical implications. J Am Acad Dermtol 2006;54:258–65.