Abstract

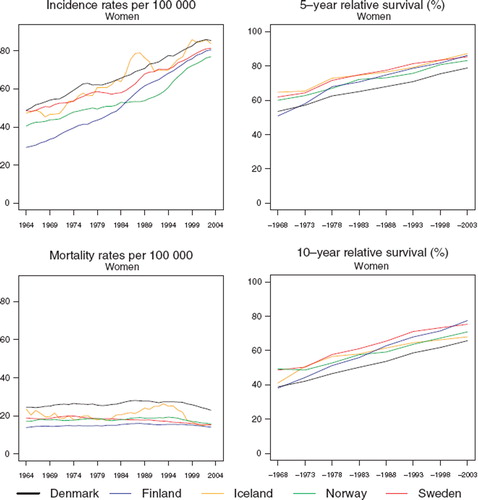

Background. Breast cancer is the leading cancer among women worldwide in terms of both incidence and mortality. European patients have generally high 5-year relative survival ratios, and the Nordic countries, except for Denmark, have ratios among the highest. Material and methods. Based on the NORDCAN database we present trends in age-standardised incidence and mortality rates of invasive breast cancer in the Nordic countries, alongside 5- and 10-year relative survival for the period of diagnosis 1964–2003 followed up to the end of 2006. Excess mortality rates are also provided for varying follow-up intervals after diagnosis. The analysis is confined to invasive breast cancer in Nordic women. Results. Incidence increased rapidly in all five countries, whereas mortality remained almost unchanged. Both incidence and mortality rates were highest in Denmark. Between 1964 and 2003 both 5- and 10-year relative survival increased by 20–30 percentage points in all countries, and 10-year survival remained around 10 percentage points lower than 5-year survival. Relative survival was lowest in Denmark throughout the period, with a 5-year survival of 79% for years 1999–2003, but 83–87% in the other countries. From 1964 the youngest women had the highest survival ratios up until the introduction of screening, when a shift occurred towards higher survival among age groups 50–59 and 60–69 in each country, except for Denmark. Excess death rates during the first months after diagnosis were highest in Denmark. Conclusion. Breast cancer survival is high and rising in the Nordic countries, and probably relates to the early implementation of organised mammography screening in each country except Denmark and a high and relatively uniform standard of living, diagnosis and treatment. Denmark stands out with higher mortality and poorer survival. The major determinants may include a failure to instigate national breast screening and a greater co-morbidity resulting from a higher prevalence of both tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption.

Breast cancer is by far the most frequent cancer among women worldwide, accounting for 26% of all cancers in females. It is also the leading cause of cancer mortality in women, representing 17% of female cancer deaths [Citation1]. In the Nordic countries, breast cancer accounted for 26% of all incident cancers and 15% of all cancer deaths among women in the period 1999–2003, amounting to 16 000 incident breast cancers and 4 500 deaths per year [Citation2]. Among the established risk factors for breast cancer are hormonally-related factors including low age at menarche, nulliparity, high age at first childbirth, short time from last full-term pregnancy, current and recent oral contraceptive use, and current and long-term hormone replacement therapy. Ionising radiation, low physical activity, obesity, alcohol intake and inherited mutations are also associated with an increased risk [Citation3]. A short interval from last full-term pregnancy is the only one of the above risk factors that has been consistently associated with poorer survival in the literature [Citation4,Citation5].

The prognosis of breast cancer patients in Europe is generally rather good, with a pooled average age-standardised 5-year relative survival of 79% for women diagnosed in 1995–1999 [Citation6]. In the EUROCARE-4 study the Nordic countries were among those with the highest survival ratios in Europe, all above 82% [Citation7], except for the Danish 5-year survival ratio which was 77%. A previous Nordic collaborative study had demonstrated a steady and large increase in the age-standardised 5-year relative survival during the period 1958 through 1987 [Citation8].

The main determinants of survival in breast cancer are stage at diagnosis [Citation9] and access to, and availability of both adequate treatment [Citation10] and screening programmes [Citation11]. Low socioeconomic status is a predictor of poorer survival [Citation12] and the difference appears to persist at least up to ten years after an initial diagnosis [Citation13]. The influence of screening on survival is however more complicated. Apart from reducing mortality from breast cancer [Citation14], screening advances the time of diagnosis of tumours [Citation15] and is associated with a degree of over-detection of both in situ and invasive tumours [Citation16], thus introducing both lead time and length biases [Citation11,Citation17].

The aim of the present study is to describe and compare trends for breast cancer incidence, mortality and relative survival from year 1964 through 2003 in the five Nordic populations, and includes a graphical presentation of excess mortality according to time elapsed from diagnosis.

Material and methods

The analysis is confined to invasive breast cancer (ICD-10 C50) in women since the incidence in men is very low. The data sources and methods are described in detail in an earlier article in this issue [Citation18]. In brief, the NORDCAN database contains comparable data on cancer incidence and mortality in the Nordic countries; data are delivered by the national cancer registries, with follow-up information on death or emigration for each cancer patient available up to and including 2006. We calculated sex-specific 5-year relative survival for each of the diagnostic groups in each country for eight 5-year periods from 1964–1968 to 1999–2003. For the last two 5-year periods, so-called hybrid methods were used. Country-specific population mortality rates were used for calculating the expected survival. Age-standardisation of survival used the weights of the International Cancer Survival Standard (ICSS) cancer patient populations [Citation19]. We present age-standardised (World) incidence, mortality, 5- and 10-year relative survival, and excess mortality rates for the follow-up periods within one month, 1–3 months, 2–5 years, 5–7 years and 7–10 years following diagnosis, as well as age-specific 5- and 10-year relative survival by country and 5-year calendar period.

Results

Incidence and mortality

In all five Nordic countries there was a quite rapid and steady increase in age-standardised breast cancer incidence over the study period, with the Danish incidence ranking first () and the range in rates between countries 74 to 86 per 100 000 in the last five-year interval. Finland had the lowest incidence up until circa year 1986, after which a rapid rise in the trend was observed. Mortality rates have been rather stable with time (), with Denmark again exhibiting the highest rate. Finland had the lowest mortality rates until the last period, with mortality thereafter converging to around 15 per 100 000 in all countries except Denmark, where the rate in 1999–2003 was around 25 per 100 000. The fluctuations in the Icelandic curves mainly reflect random variation due to the small population size, although effects of the onset of nationwide screening in 1987 are apparent.

Survival

As with incidence, there were sizable increases in both 5- and 10-year relative survival during the study period in each of the Nordic countries ( and ). The rise was steepest in Finland where the increase between the first (1964–1968) and last period of diagnosis (1999–2003) amounted to 35 and 39 percentage points for 5- and 10-year survival, respectively. Sweden and Iceland tended to have the highest 5-year survival for much of the study period, whereas Danish survival was markedly lower than in the other Nordic countries, except for the first few years when Finnish survival was also relatively low. Five-year relative survival was 79% in Denmark and between 83 and 87% in the other countries during the last period (1999–2003). In comparison, the 10-year relative survival was more than 10 percentage points lower in all countries, and estimated at 66% in Denmark, 68% in Iceland and between 71 and 77% in the other countries. Survival was highest in Sweden during the entire period, other than for diagnoses in 1999–2003 for which the Finnish survival ranked above the other populations.

Table I. Trends in survival for breast cancer by country. Number of tumours (N) included and the 5- and 10-year age-standardised (ICSS) relative survival in percent with 95% confidence intervals (RS (CI)). Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

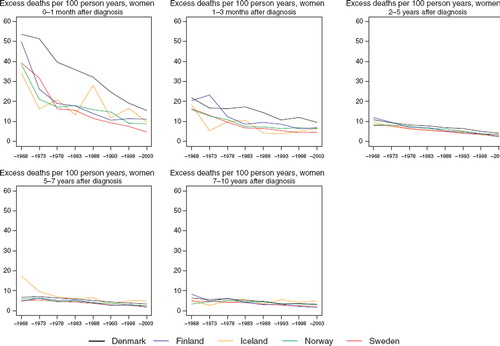

Denmark had a higher rate of excess deaths per 100 person-years during the first month after diagnosis (). All countries experienced a considerable reduction in the death rate within one month of diagnosis over the study period, with the excess mortality estimated at 15 in Denmark during the period 1999–2003 and ranging from between five and 11 per 100 person years in the other countries. The decline in excess deaths 1–3 months after diagnosis was less pronounced, with predominantly Denmark having the highest rate. Two to five years after diagnosis the excess rates were quite similar across populations, dropping from 10 to less than five excess deaths per 100 person years over time, but with a slightly higher mortality observed in Denmark. After five years of follow-up the decrease in excess mortality over calendar time was rather minor. Given the small population size in Iceland, the figures were quite unstable, particularly when considering excess deaths during the shortest periods of observation, within the first three months.

Figure 2. Trends in age-standardised excess deaths rates per 100 person years for female breast cancer by country and time since diagnosis in Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

Age-specific 5- and 10-year relative survival ratios are presented in . Until the mid-1980s, the highest 5-year survival ratios were seen in all countries among women aged 0–49 years at diagnosis. A shift appeared in Iceland and Finland in the period 1984–1988 towards the highest survival being observed among age groups 50–59 and 60–69. A similar shift occurred five years later in Sweden and still five years later in Norway but is not clearly apparent in Denmark. Even though women diagnosed after the age of 70 experienced the lowest survival, large increases with time were apparent in all countries in the oldest age groups.

Table II. Trends in 5- and 10-year age-specific relative survival in percent after breast cancer by country. Nordic cancer survival study 1964–2003.

Discussion

The relative survival of women with breast cancer increased greatly during the period 1964 to 2003 in all five Nordic countries. At the same time that incidence increased rapidly, mortality remained largely unchanged. The increase in 5-year relative survival was around 20 and 30 percentage points, with the greatest improvement in Finland. In Denmark the survival was lower than in the other Nordic countries over the entire period, and excess death rates during the first month after diagnosis were considerably higher. Breast cancer incidence and mortality were both markedly higher in Denmark than in the other countries during the entire period, whereas Finland had the lowest mortality throughout the period of investigation.

The increases in 10-year survival were at a similar level as the increases in 5-year survival. The difference between 5- and 10-year relative survival amounted to over 10 percentage points. The decrease in excess mortality over calendar time diminished with increasing duration of follow-up after diagnosis. Cancer of the female breast is one of few malignancies where relative survival continues to decline up to at least four decades after diagnosis [Citation20].

Iceland and Finland were the first countries in the world to implement national organised mammography screening programs, starting gradually in 1986 for women aged 50–59 in Finland and in 1987 for women aged 40–69 in Iceland. Even though the Swedish screening program became nationwide in 1997 (ages 50–69), implementation started already in 1974. Of the 26 Swedish counties, 15 had organised screening programs in place in 1986 and the number increased to 22 by 1992. In Norway, the screening program (ages 50–69) was implemented nationally first in 2004, but mammography screening started in 1995 in four of the 19 counties and was gradually expanded. Denmark did not roll out a national program until 2008, but implemented organised screening in four of its 16 counties in the period 1991 to 2001 (ages 50–69). The interval between invitation letters is two years in all the Nordic countries except in Sweden, where it is 18 months [Citation21,Citation22].

The early implementation of screening in Finland in combination with attendance rates exceeding 80% [Citation23] may explain part of the rapid survival increase in Finland. However, as both 5- and 10-year survival were on the rise some 20 years before the initiation of the screening, it is apparent that advances in diagnosis and treatment are also important factors.

Swedish patients had consistently higher relative survival and lower excess mortality than those in the other Nordic countries, especially soon after diagnosis. This may partly be the consequence of the relatively early centralisation of breast cancer treatment in Sweden beginning in the late-1980s and gradually extending to full implementation around 1996 with clinics specialised in breast surgery.

Explanations for the poorer Danish survival have been previously investigated by Engeland et al., who found that the proportion of patients with localised breast cancer diagnosed in the period 1978 to 1991/92 was lower in Denmark than in Finland and Norway [Citation24]. However, this did not fully explain the survival differences, as Danish patients also had the poorest prognosis within the groups of localised and non-localised tumours. This was confirmed by studies comparing Danish and Swedish breast cancer patients diagnosed in 1983–1989 and 1994 [Citation25,Citation26] that included further clinical and pathological information on the tumours. In Sweden the tumours were smaller with more node-negative axillae and well-differentiated tumours were considerably more frequent than in Denmark. Adjustment for patho-anatomical variables reduced, but did not eliminate a higher risk of death among Danish patients [Citation25]. A further analysis adjusting for the detection of tumours by mammography resulted in cancelling out the differences between Denmark and Sweden among patients diagnosed in 1994, although a higher risk of death among Danish patients diagnosed in 1989 still prevailed [Citation27].

Such findings may imply that a deficiency in early diagnosis through the lack of an organised screening programme may account for the poorer survival in Denmark. However the differences in excess deaths per 100 person-years between Denmark and the other Nordic countries are largest during the first month after diagnosis. Further, the differences almost disappeared three months from diagnosis. Thus it is possible that other factors including primary treatment with surgery and anesthesia followed by radiotherapy, or co-morbidity related to the prevalence of certain risk factors may influence the prognosis after primary treatment. Since breast cancer surgery does not require the opening of the body cavities and therefore is less life-threatening than many other types of cancer surgery, other factors – including co-morbidity – may explain the excess deaths during the first month. Breast cancer treatment in Denmark has been guided by the Danish Breast Cancer co-operative Group [Citation28–30] since the early 1980s, and research-based improvements have been adopted and implemented rapidly at the national level.

Any potential effects of the first Danish Cancer Control Plan in 2000 cannot yet be demonstrated for breast cancer patients diagnosed up to 2003. The survival among Danish breast cancer patients still remains considerably lower than among patients in the other Nordic countries, but the parallelism of the improvement in relative survival over time indicates that the advances in treatment established in Denmark are as substantial as in the other countries. The lack of national screening in Denmark probably explains part of the observed survival differences and the higher mortality, as indicated by more advanced cancers at diagnosis in Denmark than in Sweden [Citation25,Citation26]. The remaining differences may be explained in part by a higher prevalence of smoking and alcohol consumption in Denmark [Citation18,Citation31,Citation32], with the consequential deterioration of the functioning of vital organs thus increasing co-morbidity and the risk of death associated with surgery [Citation33,Citation34]. This hypothesis is corroborated by recent studies from Denmark and Sweden examining socieoeconomic position and survival after breast cancer, which reported that lower social classes had a relatively worse prognosis despite a higher incidence observed among the higher social classes [Citation12,Citation13], findings that are likely to be related both to the higher prevalence of smoking among the lower social classes and the lower compliance with screening [Citation35].

The effects of mammography screening in all countries except Denmark are reflected in the clear shift in the age-specific survival that used to be highest for women diagnosed at ages 0–49 before and around the time that screening started, but now it is highest for ages 50–59 and 60–69.

The large increase in breast cancer incidence between 1964 and 2003 can be ascribed both to the dramatic changes in exposures to reproductive and nutrition-related determinants that occurred during this period in the Nordic countries as in other western countries [Citation36], and to increased diagnostic activity, both due to mammography screening and increasing individual awareness of the disease and its symptoms. The fact that mortality has remained stable in spite of this development may be explained by concomitant advances in treatment and availability of health services, earlier diagnosis and improved general health and life-expectancy [Citation18] because of increasingly high life-standard.

It can be concluded that Nordic women diagnosed with breast cancer have, in general, a very good prognosis that has steadily improved over the last few decades. This is probably to some extent due to the early implementation of mammography screening in most of the countries, but it is also likely to be related to the relatively high standard of living and to the high standard of diagnosis and treatment in the Nordic countries. The higher mortality and poorer survival in Denmark is probably explained by a number of factors including late implementation of an organised breast cancer screening programme and a high prevalence of tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption in the population, leading to substantial co-morbidity and premature death.

Acknowledgement

The Nordic Cancer Union (NCU) has financially supported the development of the NORDCAN database and program, as well as the survival analyses in this project.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Bray F, Sankila R, Ferlay J, Parkin DM. Estimates of cancer incidence and mortality in Europe in 1995. Eur J Cancer 2002;38:99–166.

- Engholm G, Ferlay J, Christensen N, Bray F, Klint Å, Ólafsdóttir E, . (2008). NORDCAN: Cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence in the Nordic countries, Version 3.3. http://www.ancr.nu. Association of Cancer Registries, Danish Cancer Society.

- Colditz GA, Baer HJ, Tamimi RM. Breast cancer. Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni JF Jr. Cancer epidemiology and prevention. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. 995–1012.

- Kroman N, Mouridsen HT. Prognostic influence of pregnancy before, around, and after diagnosis of breast cancer. Breast 2003;12:516–21.

- Phillips KA, Milne RL, West DW, Goodwin PJ, Giles GG, Chang ET, . Prediagnosis reproductive factors and all-cause mortality for women with breast cancer in the breast cancer family registry. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2009;18:1792–7.

- Sant M, Allemani C, Santaquilani M, Knijn A, Marchesi F, Capocaccia R, . EUROCARE-4. Survival of cancer patients diagnosed in 1995-1999. Results and commentary. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:931–91.

- Berrino F, De Angelis R, Sant M, Rosso S, Bielska-Lasota M, Coebergh JW, . Survival for eight major cancers and all cancers combined for European adults diagnosed in 1995–99: Results of the EUROCARE-4 study. Lancet Oncol 2007; 8:773–83.

- Engeland A, Haldorsen T, Tretli S, Hakulinen T, Hörte LG, Luostarinen T, . Prediction of cancer mortality in the Nordic countries up to the years 2000 and 2010, on the basis of relative survival analysis. A collaborative study of the five Nordic Cancer Registries. APMIS Suppl. 1995;49:1–161.

- Sant M, Allemani C, Capocaccia R, Hakulinen T, Aareleid T, . Stage at diagnosis is a key explanation of differences in breast cancer survival across Europe. Int J Cancer 2003;106:416–22.

- Gorey KM, Luginaah IN, Holowaty EJ, Fung KY, Hamm C. Associations of physician supplies with breast cancer stage at diagnosis and survival in Ontario, 1988 to 2006. Cancer 2009;115:3563–70.

- Lawrence G, Wallis M, Allgood P, Nagtegaal ID, Warwick J, Cafferty FH, . Population estimates of survival in women with screen-detected and symptomatic breast cancer taking account of lead time and length bias. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009;116:179–85.

- Carlsen K, Høbye MT, Dalton SO, Tjønneland A. Social inequality and incidence of and survival from breast cancer in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994–2003. Eur J Cancer 2008;44:1996–2002.

- Halmin M, Bellocco R, Lagerlund M, Karlsson P, Tejler G, Lambe M. Long-term inequalities in breast cancer survival – a ten year follow-up study of patients managed within a National Health Care System (Sweden). Acta Oncol 2008; 47:216–24.

- Smith RA, Duffy SW, Gabe R, Tabar L, Yen AM, Chen TH. The randomized trials of breast cancer screening: What have we learned? Radiol Clin North Am 2004;42: 793–806.

- Møller B, Weedon-Fekjaer H, Hakulinen T, Tryggvadóttir L, Storm HH, Talbäck M, . The influence of mammographic screening on national trends in breast cancer incidence. Eur J Cancer Prev 2005;14:117–28.

- Biesheuvel C, Barratt A, Howard K, Houssami N, Irwig L. Effects of study methods and biases on estimates of invasive breast cancer overdetection with mammography screening: A systematic review. Lancet Oncol 2007;8: 1129–38.

- Autier P, Boniol M, Héry C, Masuyer E, Ferlay J. Cancer survival statistics should be viewed with caution. Lancet Oncol 2007;8:1050–2.

- Engholm G, Gislum M, Bray F, Hakulinen T. Trends in the survival of patients diagnosed with cancer in the Nordic countries 1964–2003 followed up to the end of 2006. Material and methods. Acta Oncol.

- Corazziari I, Quinn M, Capocaccia R. Standard cancer patient population for age standardising survival ratios. Eur J Cancer 2004;40:2307–16.

- Brenner H, Hakulinen T. Are patients diagnosed with breast cancer before age 50 years ever cured? J Clin Oncol 2004; 22:432–8.

- Møller B, Fekjaer H, Hakulinen T, Tryggvadóttir L, Storm HH, Talbäck M, . Prediction of cancer incidence in the Nordic countries up to the year 2020. Eur J Cancer Prev 2002;11(Suppl 1):S1–S96.

- Hofvind S, Geller B, Vacek PM, Thoresen S, Skaane P. Using the European guidelines to evaluate the Norwegian Breast Cancer Screening Program. Eur J Epidemiol 2007; 22:447–55.

- Anttila A, Koskela J, Hakama M. Programme sensitivity and effectiveness of mammography service screening in Helsinki, Finland. J Med Screen 2002;9:153–8.

- Engeland A, Haldorsen T, Dickman PW, Hakulinen T, Möller TR, Storm HH, . Relative survival of cancer patients–a comparison between Denmark and the other Nordic countries. Acta Oncol 1998;37:49–59.

- Christensen LH, Engholm G, Ceberg J, Hein S, Perfekt R, Tange UB, . Can the survival difference between breast cancer patients in Denmark and Sweden 1989 and 1994 be explained by patho-anatomical variables?–a population-based study. Eur J Cancer 2004;40: 1233–43.

- Jensen AR, Garne JP, Storm HH, Engholm G, Möller T, Overgaard J. Does stage at diagnosis explain the difference in survival after breast cancer in Denmark and Sweden? Acta Oncol 2004;43:719–26.

- Christensen LH, Engholm G, Cortes R, Ceberg J, Tange U, Andersson M, . Reduced mortality for women with mammography-detected breast cancer in east Denmark and south Sweden. Eur J Cancer 2006;42:2773–80.

- Blichert-Toft M, Christiansen P, Mouridsen HT. Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group-DBCG: History, organization, and status of scientific achievements at 30-year anniversary. Acta Oncol 2008;47:497–505.

- Møller S, Jensen MB, Ejlertsen B, Bjerre KD, Larsen M, Hansen HB, . The clinical database and the treatment guidelines of the Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group (DBCG); its 30-years experience and future promise. Acta Oncol 2008;47:506–24.

- Mouridsen HT, Bjerre KD, Christiansen P, Jensen MB, Møller S. Improvement of prognosis in breast cancer in Denmark 1977–2006, based on the nationwide reporting to the DBCG Registry. Acta Oncol 2008;47:525–36.

- Dreyer L, Winther JF, Pukkala E, Andersen A. Avoidable cancers in the Nordic countries. Tobacco smoking. APMIS Suppl. 1997;76:9–47.

- Dreyer L, Winther JF, Andersen A, Pukkala E. Avoidable cancers in the Nordic countries. Alcohol consumption. APMIS Suppl. 1997;76:48–67.

- Tønnesen H, Nielsen PR, Lauritzen JB, Møller AM. Smoking and alcohol intervention before surgery: Evidence for best practice. Br J Anaesth 2009;102:297–306.

- Janssen-Heijnen ML, Maas HA, Houterman S, Lemmens VE, Rutten HJ, Coebergh JW. Comorbidity in older surgical cancer patients: Influence on patient care and outcome. Eur J Cancer 2007;43:2179–93.

- Dalton SO, Düring M, Ross L, Carlsen K, Mortensen PB, Lynch J, . The relation between socioeconomic and demographic factors and tumour stage in women diagnosed with breast cancer in Denmark, 1983–1999. Br J Cancer 2006;95:653–9.

- Bray F, McCarron P, Parkin DM. The changing global patterns of female breast cancer incidence and mortality. Breast Cancer Res 2004;6:229–39.