Abstract

Background. Bone sarcomas in Sweden are generally referred to a multidisciplinary team at specialized sarcoma centers. This practice is strictly followed for sarcomas of long bones, but not for chest wall chondrosarcomas. Delay in diagnosis and treatment is often considerable for bone sarcomas. This report focuses on the symptoms and diagnostic problems of chest wall chondrosarcoma and factors related to long doctor's delay. Methods. The material included all 106 consecutive patients with chondrosarcoma of the chest wall diagnosed in Sweden 1980–2002. Pathological specimens were re-evaluated and graded by the Scandinavian Sarcoma Group pathology board. Files from the very first medical visit for symptoms related to the chondrosarcoma were traced and used to characterize the initial symptoms and calculate patient's and doctor's delay. Results. The most prominent initial symptom for the chest wall chondrosarcomas was a palpable mass found in 69% (73/106) of the patients at the first visit. Two-thirds of the patients experienced no local chest pain. A tumor was suspected at the first visit in 83% of the patients. Patients delay was median 3 (0–118) months and doctor's delay was 4.5 (0.1–197) months. Doctor's delay was >6 months for 40% of the patients. Patients with an initial plain chest radiograph interpreted as normal (35 patients), and/or normal or inconclusive results of a fine-needle aspiration biopsy had longer doctor's delay. Fine-needle aspiration cytology done at non-specialty units resulted in only 26% correct malignant diagnoses; at sarcoma centers 94% were correctly diagnosed. Long total delay was unfavorable. Patients who died from the chondrosarcoma had longer total delay (p<0.05). Conclusion. Chest wall chondrosarcoma presents as a lump, usually painless. Plain chest radiographs and fine-needle aspiration cytology, when done at a non-specialty center, are often normal or inconclusive. Patients should be referred to sarcoma centers for diagnosis and treatment.

Chondrosarcoma is the most common bone sarcoma in adults but still rare among the population, only 2–3 per million and year [Citation1]. Chondrosarcoma can affect virtually every bone, but has a predilection for central and axial parts of the skeleton. The most common locations are the pelvis and proximal femur, but the chest wall is the third most frequent site, accounting for approximately 15% of all chondrosarcomas [Citation2].

In Sweden, bone sarcomas are generally referred to a multidisciplinary team at sarcoma centers. Chondrosarcomas of the chest wall, however, are still often treated outside a center by thoracic or general surgeons [Citation3]. We have recently shown that the 10-year survival rate was 75% for patients treated at a sarcoma center as opposed to 59% for those not referred. In this study we sought reasons why many of these patients are not referred to a sarcoma center [Citation3].

The only effective treatment for chondrosarcoma is surgery with wide surgical margins. An early diagnosis when the tumor is small increases the possibility of a curative treatment. Doctor's delay in cancer treatment and its role for outcome is open to debate. In bone sarcoma this delay often is considerable. Our purpose with this study was to characterize the initial symptoms and clinical features of chest wall chondrosarcoma and focus on the diagnostic process, delays and its impact for outcome.

Patients and methods

All patients with chondrosarcoma of the chest wall diagnosed in Sweden from 1980–2002 were identified from the National Swedish Cancer Register and the Scandinavian Sarcoma Group (SSG) Register. One hundred and twenty three patients with ICD-10 location code C413 (rib, sternum and clavicle) were identified. After exclusion of nine patients with chondrosarcoma of the clavicle, three patients with misclassified tumor location (two scapula and one spine), and one patient with radiation induced chondrosarcoma there remained 110 patients. Chondrosarcoma of the clavicle were excluded as it is not a flat bone and thereby differs from rib and sternum. Clinical files were collected for each patient from the diagnosing and treating hospitals. Pathological specimens were reviewed by the SSG Pathology Board (blinded to outcome) and classified as Grade 1 to 4, where Grade 4 represents dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma. Tumor size was designated by the greatest dimension as measured from the surgical specimens. After exclusion of four cases because the diagnosis of chondrosarcoma was not supported by the Pathology Board there remained 106 patients for analysis.

Patient records for the first medical consultation for symptoms or with incidental clinical findings which could be related to the primary bone malignancy were obtained by backtracking from the records of the clinics where the diagnosis of chondrosarcoma was established.

Patient's delay was defined as the time from when the patient first noted symptoms until the time of the first medical visit. Doctor's delay was defined as the period from the first medical visit for symptoms related to the chondrosarcoma to the first day of treatment. Total delay was equal to the summary of patient's and doctor's delay.

Additional data registered were sex, age at diagnosis, pain, palpable mass, history of trauma, radiographic interpretation, patient's delay, doctor's delay, total delay, fine needle aspiration cytology, localization, tumor size, histological grade, and treatment at a sarcoma center.

Statistical analysis was performed with Statistica, statsoft; statistical analyses used were Mann Whitney U-test and χ2 test, significance level was set to p<0.05. Patient survival was calculated with Kaplan-Meier analysis and differences in prognostic factors with the log-rank test.

Results

From January 1, 1980 through December 31, 2002, 106 patients with chondrosarcoma of the chest wall were diagnosed, 57 males and 49 females, with a mean age of 57 years for both sexes at diagnosis. Eighty-nine were located in the ribs and 17 in the sternum. Only three had a secondary chondrosarcoma, two patients with multiple exostoses and one with Olliers disease. Ninety-seven of the 106 were treated in a curative intent (19 grade 1, 39 grade 2, 31 grade 3 and 8 grade 4) [Citation3].

Symptoms

The dominating initial symptom was a palpable mass reported by 70 of the patients. Males had a mass in 72% (41/57) and females in 59% (29/49). The palpable mass was usually painless, only 12 reported pain. Thirty-two percent (34/106) of the patients reported diffuse chest pain. None reported periods of fever, pain at night, weight loss or general illness. The chondrosarcoma was discovered incidentally in 13% of the patients (three noted a mass at the physical examination and in 11 at a chest x-ray conducted for other reasons). Twenty-three percent (13/57) of the males and 12% (6/49) of females related the onset of symptom to a minor chest wall trauma.

Physical findings at the first visit

On the physical examination, the doctor confirmed the palpable mass noticed by 70 of the patients themselves and detected a lump in another three subjects. Thereby, totally 69% (73/106) of the patients had a mass at the time of the first medical visit. For 60 patients the mass was measured with a mean of 65 (20–240) mm. It was characterized as bone hard in 64, soft in two, and not specified in seven cases. Local tenderness over the mass in the chest wall was reported by the physician in 32 cases.

Initial diagnosis

A tumor was suspected at the first medical visit in 88 of the patients, including the 14 discovered incidentally. Pleurisy/infection was the initial diagnosis for four, rib fracture/muscle strain for ten, and other diagnoses for four.

Radiographic examination

The results of the initial chest radiographs were found for 104 cases. These were interpreted as normal in 35 of the subjects and pathological in the remaining 69. A tumor was suspected in 61 of the 69. Radiographs interpreted as normal were more common among women (50%) than among men (20%) (p<0.01, χ2 test). High grade (grade 3 and grade 4) chondrosarcomas had a normal interpreted x–ray in 41% compared to low grade (grade 1 and grade 2) in 32%.

Fine needle aspiration cytology

Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) was requested for 66 patients on suspicion of a malignant tumor. For 34 patients the FNAC was performed by a cytopathologist at a sarcoma center and resulted in 32 malignant cytological findings and two inconclusive. FNAC performed on 39 patients at non-specialty units resulted in five benign, ten malignant and 24 inconclusive diagnoses. This difference in accuracy in fine needle aspiration cytology between sarcoma centers and non-specialty units was important for outcome. A benign or inconclusive diagnosis, at non-specialty units, resulted in a shelling-out procedure with poor surgical margins (). The results of FNAC at non-specialty units were not helpful in discriminating between histologically high-grade and low-grade chondrosarcomas ().

Table I. Chondrosarcomas of the chest wall. Surgical margins in relation to results of fine-needle aspiration cytology at non-specialty centers (39 patients).

Table II. Chondrosarcomas of the chest wall. Diagnosis at non-specialty centers. Results of fine-needle aspiration cytology compared with histological grade at operation.

Delay in diagnosis and treatment

Both patient's and doctor's delay had a wide range, from only a week to more than a decade! Patient's delay was median 2.5 (0–118) months and doctor's delay 4.5 (0.1–197) months. Median total delay was 8 (1–199) months. One-quarter of the patients consulted a physician within two weeks from first noticing the mass and one-quarter waited more than six months. Patients who related the onset of symptoms to a chest wall trauma had a short delay, <one week, or long delay, >six months. Doctor's delay was not significantly shorter in the second part (1991–2002) than in the first part of the study period (1980–1990).

Doctor's delay for 20% of the cases was between six months and one year and in another 20% it exceeded one year. Despite the first doctor suspected a malignancy doctor's delay was long.

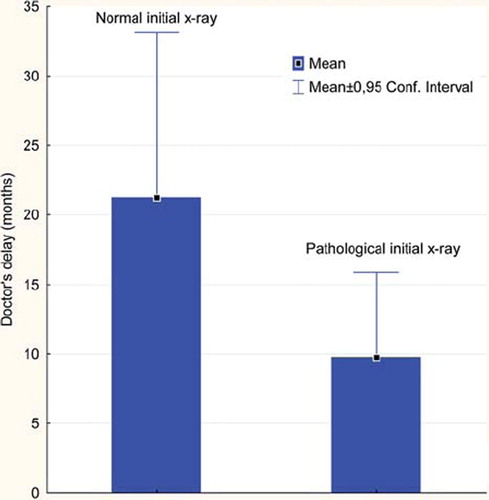

A radiographic examination which was interpreted as normal resulted in longer doctor's delay (p<0.03, MWU-test). Mean doctor's delay in patients with a normal interpreted radiograph was 21 months (median 6) compared to 9.5 months (median 3.5) for those with a pathological findings at the initial radiograph ().

Figure 1. Doctor's delay was longer in chest wall chondrosarcoma patients with an initial x-ray interpreted as normal. (p<0.05, MWU-test).

Benign or inconclusive FNAC was also a factor contributing to longer doctor's delay. The 17 patients for whom no FNAC was requested and who were treated outside a sarcoma center had a median doctor's delay of 18 months (p<0.05, MWU-test). These patients were told to return if the tumor became bigger. When they did, the now large lesion was excised with intralesional margins.

Ninety-seven of the 106 patients were treated with curative intent. Among the remaining nine patients; four had radio and chemotherapy, one was operated to reduce tumor bulk and four had no treatment. These patients had a mean doctor's delay of 35 months (median six months).

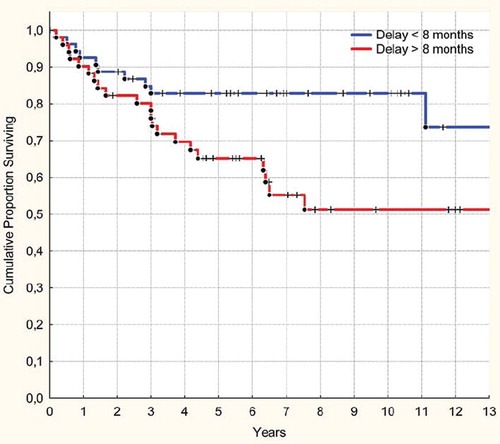

Delay and outcome

Total delay was related to outcome. Patients with long total delay had significantly higher risk of tumor related death (p<0.05, log-rank test) (). Doctor's delay was also longer in the group of patients who died from the chondrosarcoma, however the difference was not significant (p=0.16).

Discussion

Our series, 106 patients with verified chondrosarcoma of the thoracic cage, is the largest series published to date. These 106 cases in a 22-year period in a population of around nine million gives an expected yearly incidence corresponding well with the 0.5 cases per million reported by others [Citation2].

The patients were identified from the Swedish Cancer Register. The Swedish Cancer Register includes all patients with a malignant tumor diagnosed since 1958. It is based on a double reporting system; both the clinician and the pathologist must report every new patient diagnosed with a malignant tumor. The Swedish Cancer Register is widely used not only as an important tool to monitor cancer incidence and survival but also for research purposes. The overall completeness of the Swedish Cancer Registry is high and 99% of all cases are morphologically verified [Citation4].

The possibilities inherent in the national cancer register coupled with the continually updated census system gives an unique opportunity for tracing all patients and their medical records and for extracting information about delays in diagnosis and treatment.

For diagnosis and treatment, the patient has to take the initiative. Most patients noted a painless, slowly-growing mass not giving much discomfort. Only one-third experienced chest pain, usually mild. This feature probably explains the wide range in patient's delay from less than two weeks to nearly ten years.

Once in the doctor's office, what happened? In most previous reports dealing with doctor's delay for bone sarcomas, the main explanation for the delay was the rareness of the disease [Citation5,Citation6]. In our series, however, a tumor was suspected in 88 of the 106 patients at the first consultation. Still, doctor's delay, from suspicion to treatment, exceeded six months for 40% of the patients. We have identified several factors contributing to doctor's delay.

In the first place, a painless mass as noted by two-thirds of the patients at their initial consultation did not incite diagnostic celerity. We believe that this painlessness is an important finding. The possibility of a chondrosarcoma, even in the absence of pain, has to be considered in the differential diagnosis of a mass in the chest wall. Other reports, based on referred patients, regard pain as a dominating symptom for malignancy and the absence of pain as an indicator of a benign mass [Citation7–9]. We differ on this important point. The absence of pain at the time of the very first medical examination of our chondrosarcoma patients undoubtedly contributed to both patient's delay and doctor's delay. A possible explanation for the absence of pain is that the ribs and sternum are not weight-bearing bones [Citation10].

Secondly, a radiograph first interpreted as normal, as was the case for 35% of the patients, led to a significantly prolonged doctor's delay. Both patient and doctor tended to regard the mass as harmless, although still without a clear diagnosis, and not requiring a repeated or a more sophisticated radiographical procedure than a plain chest film.

Thirdly, the results of FNAC, when inconclusive or benign, contributed to doctor's delay. At non-specialty centers, only 26% of the chondrosarcomas sampled were correctly diagnosed as malignant. At sarcoma centers, 94% were correctly diagnosed by the same procedure. An inconclusive or a benign FNAC result at non-specialty centers lulled both patient and doctor into accepting the mass as harmless and prolonged the time to treatment. At sarcoma centers and faced with a mass involving the thoracic wall, inconclusive or benign FNAC results are not accepted; the FNAC is repeated or an open biopsy is done [Citation11]. The lesson from this is that all patients with a suspected bone tumor should be referred, untouched, to a sarcoma center and that all biopsies, whether FNAC, true-cut or open, should be done at sarcoma centers with a multidisciplinary group for diagnosis and treatment [Citation12]. Our results confirm that FNAC is unreliable outside sarcoma centers and even high grade chondrosarcomas were missed ().

During the study period, 1980–2002, new radiological modalities have been introduced and integrated in medical practice. Despite these radiological advances such as computer tomography and magnetic resonance imaging, doctor's delay was not significantly shorter in the second half of the study period.

The consequences for the patients not quickly referred to a sarcoma center are dire. At non-specialized centers, with an inconclusive or benign FNAC result and with general or thoracic surgeons without experience of sarcoma diagnosis and surgery, many patients were treated inadequately with a high proportion of intralesional procedures with tumor spillage and early local recurrence. We have shown that these patients have a significantly higher risk for death in uncontrolled disease [Citation3]. There is no effective adjuvant treatment. Only a well-planned and extensive surgical excision can cure the patient. Only half the patients with local recurrence can be cured by repeated excisions.

Like chondrosarcomas, soft tissue sarcomas are uncommon, occur in the same age group in adults and typically present as a painless mass. However, doctor's delay for soft tissue sarcomas has been reported to be much shorter – exceeding one month for only a quarter of the patients [Citation13]. Increasing physician awareness of the possibility of a chondrosarcoma when presented with a chest wall mass will hopefully shorten the time to diagnosis and treatment.

Although there is general agreement that early diagnosis and treatment are of benefit in malignant disease, some studies find no apparent correlation between delay in diagnosis and prognosis for chondrosarcoma [Citation14–17]. However, in our series, with Kaplan-Meier analysis the survival rate was higher for those with shorter total delay (). Rougraff et al. relied on the information concerning initial symptoms and delay given at admission to the tumor center [Citation16]. Instead, we have traced medical files from the period before chondrosarcoma diagnosis until we found the file from the first medical visit. This methodological difference could explain the contradictory results.

Nine patients in our series could not be treated with curative intent. For several of these, extremely protracted doctor's delay (mean 35 months), had allowed the tumor to grow to an inoperable extent.

Chest wall bone tumors are more often malignant than benign and should be considered as malignant until proven otherwise [Citation18]. Pain or lack of pain is not discriminatory. If the mass arises from a rib or sternum the patient should be referred to a specialized sarcoma center for diagnosis and treatment. Changes in referral practice will improve the outcome for chondrosarcoma of the chest wall.

Declaration of interest statement: There is no conflict of interest to be declared.

References

- Lee FY, Mankin HJ, Fondren G, Gebhardt MC, Springfield DS, Rosenberg AE, . Chondrosarcoma of bone: An assessment of outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1999;81: 326–38.

- Burt M, Fulton M, Wessner-Dunlap S, Karpeh M, Huvos AG, Bains MS, . Primary bony and cartilaginous sarcomas of chest wall: Results of therapy. Ann Thorac Surg 1992;54:226–32.

- Widhe B, Bauer HCF. Surgical treatment is decisive for outcome in chondrosarcoma of the chest wall: A population-based Scandinavian Sarcoma Group study of 106 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009;137:610–4.

- Barlow L, Westergren K, Holmberg L, Talback M. The completeness of the Swedish Cancer Register: A sample survey for year 1998. Acta Oncol 2009;48:27–33.

- Schnurr C, Pippan M, Stuetzer H, Delank KS, Michael JW, Eysel P. Treatment delay of bone tumours, compilation of a sociodemographic risk profile: A retrospective study. BMC Cancer 2008;8:22.

- Wurtz LD, Peabody TD, Simon MA. Delay in the diagnosis and treatment of primary bone sarcoma of the pelvis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1999;81A:317–25.

- Faber LP, Somers J, Templeton AC. Chest-wall tumors. Curr Probl Surg 1995;32:666–747.

- King RM, Pairolero PC, Trastek VF, Piehler JM, Payne WS, Bernatz PE. Primary chest-wall tumors – Factors affecting survival. Ann Thorac Surg 1986;41:597–601.

- Flemming DJ, Murphey MD. Enchondroma and chondrosarcoma. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol 2000;4:59–71.

- Bjornsson J, McLeod RA, Unni KK, Ilstrup DM, Pritchard DJ. Primary chondrosarcoma of long bones and limb girdles. Cancer 1998;83:2105–19.

- Kreicbergs A, Bauer HCF, Brosjo O, Lindholm J, Skoog L, Soderlund V. Cytological diagnosis of bone tumours. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1996;78B:258–63.

- Mankin HJ, Lange TA, Spanier SS. The hazards of biopsy in patients with malignant primary bone and soft-tissue tumors. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1982;64:1121–7.

- Brouns F, Stas M, De Wever I. Delay in diagnosis of soft tissue sarcomas. Eur J Surg Oncol 2003;29:440–5.

- Briccoli A, Rocca M, Salone M, Palmerini E, Balladelli A, Ferrari C, . Local and systemic control of Ewing's Bone Sarcoma family tumors of the ribs. J Surg Oncol 2009;100: 222–6.

- Grimer RJ. Size matters for sarcomas! Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2006;88:519–24.

- Rougraff BT, Davis K, Lawrence J. Does length of symptoms before diagnosis of sarcoma affect patient survival? Clin Orthop 2007;462:181–9.

- Bacci G, Di Fiore M, Rimondini S, Baldini N. Delayed diagnosis and tumor stage in Ewing's sarcoma. Oncol Rep 1999;6: 465–6.

- Hughes EK, James SLJ, Butt S, Davies AM, Saifuddin A. Benign primary tumours of the ribs. Clin Radiol 2006;61: 314–22.