Abstract

Background. We studied compliance to guidelines of curative treatments in prostate cancer (PCa), which were of special interest due to recent introduction of new treatment technologies and the fact that there existed a real choice between surgery and radiotherapy. Material and methods. We did retrospective analyses of guidelines adherence for all PCa patients receiving curative treatment at the Norwegian Radium Hospital from 2004 to 2007 after the introduction of robot-assisted prostatectomy and after-loading brachytherapy. The patients were classified into three groups in relation to guidelines: the accordance, accordance after discussion, and the deviance groups. In time Period I (2004–2005) the 2003 EAU guidelines were used and in Period II (2006–2007) in-house guidelines with minor modifications of EAU were applied. Results. During the observation period 859 patients had curative treatment for PCa, and 83% of the patients were treated according to guidelines. In the deviance group (N=146), 119 men (82%) got prostatectomy instead of radiotherapy. The reasons for deviation in the second period were age >65 years (N=70) and surgery in cases with T3 tumors (N=10), Gleason score >8 (N=13) and combinations (N=26). Deviances from guidelines in the radiotherapy group (N=27) mainly concerned patient selecting this treatment due to expectations of preserving sexuality and/or fertility. Conclusions. In spite of acceptable overall compliance to guidelines for curative PCa treatment, the proportion of non-adherence should not been overseen, in particular when new treatment technologies are introduced. Guidelines for PCa need to be monitored regularly, and the compliance to guidelines has to be assessed on a regular basis. Guidelines should avoid too strict criteria, particularly in relation to age.

Guidelines in oncology are systematically developed statements concerning evaluation, treatment and aftercare for specific types of cancer [Citation1]. Guidelines provide comprehensive documentation of treatment alternatives which should be discussed by the clinicians and their patients [Citation2]. Guidelines are also relevant for doctors in order to make best decisions about treatment, and to patients who can check that they are offered appropriate treatment. For hospital owners guidelines represent an important tool for making administrative decisions concerning volume and costs of required medical interventions, especially in the case of introducing new treatment technologies. An advantage of guidelines is that treatment of the individual patient can be based on documented evidence from clinical research and practice [Citation3]. Guidelines are not commands, and should not replace patient-centered decision making [Citation4].

However, critical comments toward guidelines have also been raised and some clinicians oppose the application of guidelines to their practice [Citation5]. For example, Grol [Citation6] stated that many guidelines were based on experts’ opinions rather than on high degrees of evidence. In addition, in his view, recommendations often reflected personal opinions, local culture, or personal interests of the guideline developers.

At the hospital level international guidelines must often be modified in relation to local conditions, based on available technical and financial resources and related to patient demands often influenced by the media. Such in-house (local) guidelines monitor the institution's policy and provide the frames for treatments offered.

On this background, we found it worthwhile to illustrate the use of guidelines by the application of curative treatment of prostate cancer (PCa) as practiced by the clinicians at a comprehensive cancer center. We chose PCa as a model because optimal curative treatment of PCa is still under discussion. Further, during the last two decades the importance of adherence to international consensus guidelines for treatment of PCa has been acknowledged for the use of surgery, radiotherapy and hormone treatment, and their combinations. For instance, the guidelines of the European Association of Urological (EAU) from 2001 and with later regular revisions reflect the multimodality approaches for PCa recommended for urologists and radiotherapists all over Europe [Citation7]. The EAU guidelines of 2003 concerning curative treatment of PCa are displayed in the left part of [Citation8]. These guidelines provide several options without forced choices between them.

Table I. The criteria of the EAU Guidelines on prostate cancer 2003 [Citation8] and the NRH Guidelines 2005.

The Norwegian Radium Hospital (NRH) is a major comprehensive cancer center and a tertiary referral hospital for patients with localized PCa from the Southern part of Norway, who are in need of radiotherapy or specialized surgery. Guidelines-based treatment of PCa is therefore a viable option at the NRH where urologists and oncologists work closely together in discussion and planning of the optimal treatment of the individual patient [Citation9].

The present study explores the use of guidelines at NRH in relation to curative treatment of PCa from late 2004 to mid 2007. This time period was chosen as robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy (RALP) and after-loading brachytherapy were introduced as new treatment technologies at NRH during 2004. We compared adherence to guidelines in two time periods: Period I from December 2004 to December 2005 when the EAU guidelines of 2003 were valid, and Period II from January 2006 to July 2007, when modified in house guidelines were stated, based on gained experience with the new technologies and new findings from international literature. For both time periods our hypothesis was that high compliance with current guidelines was the rule, though “enthusiastic” application of the new technologies could lead to increasing guideline deviation. When practice eventually deviated from guidelines, we investigated the reasons for this in detail.

Methods

The two sets of guidelines

Period I. In 2004/5 a slightly modified version of the EAU 2003 guidelines [Citation8] was agreed on at NRH for curative treatment of PC at the institution (). In these guidelines the cancer-related criteria were self-explanatory, and they were generally easily retrievable from the medical records. The criterion of life expectancy left an opportunity for individual clinical interpretation, which not always was sufficiently documented. However, in general, our clinicians interpreted this criterion as an upper age limit of 70 years for surgical and 75 years for radiotherapy patients, since the mean life expectancy from birth in Norwegian males was 78 years [Citation10].

Period II. After several discussions between the urologists and oncologists, the NRH guidelines were formally documented in October 2005. These guidelines provided treatment recommendations for patients with local or locally advanced PCa, replacing those of Period I. The upper age limit was, changed, however, influenced by the publication from the SPCG IV trial [Citation11] in May 2005, which documented that surgery did not improve survival in patients aged ≥65 years ().

During the whole study period the hospital's urologists and oncologists met at least once a week to discuss and determine the individual patient's treatment based on information from the referral letter, supplementary examinations at the out-patient department, and the current guidelines.

Patients

The patients eligible for the present retrospective study fulfilled all five selection criteria: 1) Referred to NRH for curative treatment of adenocarcinoma of the prostate; 2) Initial cancer diagnosis ≤24 months before the start of curative treatment excluding patients treated by “active surveillance” [Citation12]; 3) Curative treatment as the patient's first treatment applied between December 1, 2004 and June 30, 2007; 4) Treatment by either RALP or radiotherapy, the latter preceded by obturatory lymphadenectomy in cases with PSA >10 mg/l or T-category >T2c or Gleason score >7; 5) Age ≤75 years, and 6) No previous invasive cancer.

The medical records of eligible patients were reviewed for TNM classification (1997) [Citation13], Gleason score of the prostate biopsies, and pre-treatment PSA values. All patients were allocated to a pre-treatment risk group according to D'Amico et al. [Citation14].

Treatment options

Surgery. Prostatectomies were performed by robot-assisted surgery with or without lymphadenectomy. RALP was performed by a five port transperitoneal approach using a 3-arm da Vinci® system introduced in December 2004 [Citation15].

Radiotherapy. Patients belonging to the low-risk group were irradiated using a conformal 4-field box technique (50 Gy to the seminal vesicles and 74 Gy to the prostate) without anti-androgen treatment. Increasingly, the local non-surgical treatment in patients belonging to the intermediate and high-risk groups included a combination of conformal radiotherapy and high-dose rate brachytherapy as a boost [Citation16]. Three year of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) was used in addition to conformal radiotherapy in patients of the intermediate or high-risk groups.

Patients with less than three positive tumor-infiltrated pelvic lymph nodes were included in a protocol of Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy (IMRT) to the pelvis.

Group allocation in relation to guidelines

For the purpose of our study the patients were allocated to one of three alternative groups based on the recommendations of the guidelines and the treatment they had received:

Treatment according to guidelines (according group) contained cases for whom guideline recommendations and given treatment (surgery and all types of radiotherapy) were in accordance without discussion between the medical specialists.

Treatment according to guidelines after discussion (discussion group) covered less obvious cases for which finally treatment according to guidelines was decided upon after discussion between the medical specialists and the patient.

Treatment deviating from guidelines (deviance group) concerned patients who fulfilled the guideline criteria for either prostatectomy or radiotherapy, but who did not get the recommended treatment. The surgical deviance group thus consisted of patients who got prostatectomy although the guidelines recommended radiotherapy, whereas the radiotherapy deviance group consisted of patient who got radiotherapy although surgery was recommended according to the guidelines.

Statistical considerations

The data were analyzed with SPSS, version 15. Continuous variables were analyzed with t-tests, and categorical variables with Pearson's χ2 test. Non-parametric testing was used in the case of skewed distributions. The significance level was set at p<0.05 and all tests were two-sided.

Ethics

This study was part of a larger study of patients with PCa, and all patients gave written informed consent. The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics of Southern Norway, the Norwegian Data Inspectorate, and the institutional review board at NRH.

Results

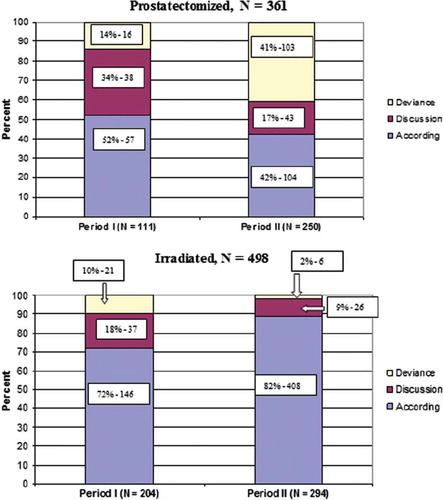

A total of 859 patients were included in this study, 315 (37%) patients during Period I and 544 (63%) in Period II (). A total of 596 patients (66%), 144 (17%) and 146 patients (17%) were allocated to the according, discussion and deviance groups, respectively. In spite of a trend toward increased Gleason score and higher PSA values during Period II compared to Period I, no significant difference emerged for the distribution between the three guideline groups (). However, a significantly greater proportion of patients had surgery during Period II (Period I: 35%; Period II: 46%) ().

Table II. Characteristics of the samples of Period I (2004 – 2005) and Period II (2006 – 2007).

Of the 146 patients in the deviance group 119 men (82%) had been operated and 27 had radiotherapy. The surgical group increased by a factor of three (14% vs. 41%) from in Period I to Period II. In contrast, the number of irradiated patients decreased from 10 to 2% ().

The most frequent reason for membership of the deviance group was non-adherence to the defined cut-off age in 86 patients, resulting in the only significant difference between the study periods in the deviance group (5% in Period I and 84% in Period II) (). For example, 84 patients aged >65 years had surgery during Period II, and in 70 of them age was the only reason for allocation to the surgical deviance group. Twenty-seven patients (Period I: 8 and 19 in Period II) received surgical treatment in spite of a T3 tumor, and in 19 (Period I: 2 and 17 in Period II) men a Gleason score ≥8 had been demonstrated in the pre-RALP biopsies. There were, however, no statistical differences in the distribution of Gleason score, T category, median PSA value or D'Amico risk score ().

Table III. Characteristics of the deviance group in relation to time Period I and II.

According to the medical records 87 men (73%) in the surgical deviance group had chosen their treatment based on the information received from the referring physician and/or the urologist at NRH. In eight patients (6%) surgery was preferred due to major pre-existing intestinal, urinary or vascular morbidity considered as reasonable contraindications for radiotherapy. In the remaining 24 patients (20%) of the surgery deviance group, the reasons for non-compliance to the guidelines could not be identified in their medical records.

None of the 27 patients of the radiotherapy deviance group had hormone treatment, while 19 had a T category of ≤2a and eight had a T category of ≥2b. A Gleason score ≤6 was present in 14 patients and 13 had a Gleason score of 7. Fourteen of 27 patients (52%) had themselves chosen radiotherapy, and in four of them with an explicit expectation of preserving sexuality and/or fertility. In five of the patients co-morbidity was the reason for radiotherapy. For the remaining nine patients (33%) of the radiotherapy deviance group, the reasons for non-compliance to the guidelines could not be identified in the medical records.

Discussion

Overall 88% of the patients of Period I were treated according to EAU 2003 guidelines, while this proportion was 80% in Period II with NRH guidelines, and this difference was non-significant. The surgical deviance group increased from 14 to 41% from Period I to II, while the radiotherapy deviance group decreased from 10 to 2%. The most frequent reason for deviance in the surgery group was non-adherence to the defined cut-off age, and for radiotherapy it was personal wishes of the patients. Our results emphasize some problems related development use and revision of guidelines. Firstly, guidelines need to be revised regularly in order to reflect progress in treatment and understanding of tumor biology, and changes in relevant characteristics of the patients. As indicated by our results, such revisions are particularly important when new developments concerning evaluation and treatment opportunities accumulate rapidly such as recently seen in the treatment of PCa. If revisions are delayed, there is a risk that deviations from guidelines will increase in number due to these new and promising therapeutic opportunities and not at least due to increasing demands from patients.

Secondly, recommendations in guidelines should not be too strict. On the other hand in their day-to-day therapeutic decisions clinicians must have easily understandable criteria. Retrospectively we have to admit that the strictly defined age limit of 65 years for RALP during Period II was too low, on the background of Norwegian men's life expectancy of 78 years, and the minimal surgical trauma represented by RALP when used by experienced urologists. Further, life tables demonstrate that about half of Norwegian men at an age 75 years have a life expectancy of ≥10 years [Citation10]. This implies a general improvement of the health of Norwegian men, which already was among the highest in Europe. This points to another problem of guidelines, namely that they should be relevant in a broad range of countries, which have different levels of general health in their populations as well in their offers of health care.

Our adjustment of guidelines for surgery in 2005 was heavily influenced by the findings of SPCG IV trial, which indicated that surgery did not increase survival in patients aged ≥65 years [Citation11]. Retrospectively, we should not exclusively have relied on the cut-off used in one single sub-group analysis especially when the authors are uncertain about the interpretation. We showed that the guideline-based age limit of 65 years was not strictly adhered to during the day-to-day discussions between urologists and radiotherapists. The discrepancy between the written NRH guidelines with respect to age and everyday clinical practice is the main reason for the high proportion of prostatectomized patients allocated to the deviance group. This finding supports the view that future in-house guidelines should consider biological age rather than chronological as done in Period I.

Thirdly, the increase of the surgical deviance group from Period I to II should also be considered in the context that NRH was the first hospital in Norway to offer robotic prostatectomy. This technical achievement was followed by enthusiastic reports from the patients` organization and the media about shorter hospitalization times and lower operative morbidity compared to open prostatectomy, leading to increased patients demands for RALP. This enthusiasm has probably led to an increasing number of patients referred to NRH, with the prospect of robotic prostatectomy being the primary reason for referral.

The gradual technical perfection of the urological team and their experience that even relatively large tumors could be removed successfully are also importance for the findings of the surgical deviance group. This may in part explain why an increasing number of patients with T3 tumors have been operated on instead of receiving radiotherapy according to the 2005 guidelines. In agreement with our experience, recent studies also suggest that patients with high Gleason score of 8–10 can benefit on prostatectomy and can provide durable local control, and favorable cancer-specific survival [Citation17].

A final reason for the relative high number of patients in the surgery deviance group is that some patients could not be irradiated due to prior extensive abdominal surgery for Crohn's disease, ulcerous colitis, and other types of pelvic morbidity.

Our principal view is that the establishment of thoroughly discussed and accepted institutional guidelines is a prerequisite for optimal clinical practice at a comprehensive cancer center where different treatment options are available. Subsequent medical practice has to follow two strategies. First, any reason for deviance from guidelines should be carefully documented in the patient's medical record. Second, regular monitoring with compliance to guidelines should be performed, as well as continuous guideline revisions based on the latest available research evidence. As a result of our study the institutional NRH guidelines were revised in 2008, in line with recent revisions of the EAU 2008 guidelines [Citation18]. In particular, no specific age limits were defined for the treatment types.

This study reflects daily uro-oncological practical use of guidelines at a large Scandinavian comprehensive cancer center during a defined time period with important technical changes in the treatment of prostate cancer. Though the single institution design of the survey might be viewed as a limitation, we believe that other comparable institutions experience similar guideline deviations and face the need to analyze compliance.

Conclusions

Curative treatment of PCa at a comprehensive cancer center was based on international and institutional guidelines. Overall compliance with these guidelines was high, but different adherence patterns for surgery and radiotherapy point to the need for regular compliance monitoring. The guidelines need to be revised regularly in order to incorporate changes in treatment technology and patients’ characteristics. One should be careful to state too strict limits in guidelines, as illustrated by age limits.

Acknowledgements

Andreas Stensvold, MD, PhD-fellow holds a PhD-grant from the Norwegian Cancer Society.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Clinical Resource and Audit group. Clinical guidelines. Edinburgh: Scottish Office; 1993.

- Shaneyfelt TM, Mayo-Smith MF, Rothwangl J. Are guidelines following guidelines? The methodological quality of clinical practice guidelines in the peer-reviewed medical literature. JAMA 1999;281:1900–5.

- Baiardini I, Braido F, Bonini M, Compalati E, Canonica GW. Why do doctors and patients not follow guidelines? Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2009;9:228–33.

- Antman EM, Gibbons RJ. Clinical practice guidelines and scientific evidence. JAMA 2009;302:143–4.

- Shaneyfelt TM, Centor RM. Reassessment of clinical practice guidelines: Go gently into that good night. JAMA 2009;301: 868–9.

- Grol R. Has guideline development gone astray? Yes. BMJ 2010;340:c306.

- Aus G, Abbou CC, Pacik D, Schmid HP, van Poppel H, Wolff JM, . EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Eur Urol 2001;40:97–101.

- Aus G, Abbou CC, Bolla M, Heidenreich A, Schmid HP, Van Poppel H, . EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Available from: http://www.uroweb.org/fileadmin/tx_eauguidelines/. February 2003.

- Lilleby W, Hernes E, Waehre H, Raabe N, Fossa SD. [Treatment of hormone-resistant prostate cancer]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2006;126:2798–801.

- Statistics Norway. Available from: http://www.ssb.no/. March 2010.

- Bill-Axelson A, Holmberg L, Ruutu M, Häggman M, Andersson SO, Bratell S, . Radical prostatectomy versus watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1977–84.

- Klotz L. Active surveillance with selective delayed intervention for favorable risk prostate cancer. Urol Oncol 2006;24:46–50.

- Fleming ID, Cooper JS, Henson DE, Hutter RVP, Kennedy BJ, Murphy GP, . American Joint Committee on Cancer staging manual. 5th. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott: 1997. 219–22.

- D'Amico AV, Whittington R, Malkowicz SB, Schultz D, Blank K, Broderick GA, . Biochemical outcome after radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or interstitial radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA 1998;280:969–74.

- Murphy DG, Kerger M, Crowe H, Peters JS, Costello AJ. Operative details and oncological and functional outcome of robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: 400 cases with a minimum of 12 months follow-up. Eur Urol 2009;55:1358–66.

- Raabe NK, Lilleby W, Tafjord G, Astrom L. [High dose rate brachytherapy in prostate cancer in Norway]. Tidsskr nor laegeforen 2008;128:1275–8.

- Karnes J, Hatano T, Blute ML, Myers RP. Radical prostatectomy for high-risk prostate cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2010;40:3–9.

- Association of Urology. Homepage Association of Urology, EAU Guidelines. Available from: http://www.uroweb.Org/. March 2009.