Abstract

Background. Cervical carcinoma is the only gynecological tumor still being staged mainly by clinical examination and only a limited use of diagnostic radiology. Cross sectional imaging is increasingly used as an aid in the staging procedure. We wanted to assess the impact of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in addition to the clinical staging of patients with carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Material and methods. A retrospective single-centre analysis of 183 women referred to a tertiary referral centre for gynecological tumors (≤ 65 years old) with cervical cancer diagnosed between January 1, 2003 and December 31, 2006 who have undergone an MRI investigation before start of treatment. Patient records were retrospectively reviewed and any change of the planned treatment after the MRI examination was noted. Results. In patients with cervical carcinoma FIGO stage Ia2-IIa treated surgically, the treatment plan was altered due to MRI results in 10/125 patients. In the smaller group of patients with clinically more advanced disease receiving radio-chemotherapy, the treatment plan was altered in 12/58 patients. Reasons for changing the treatment plan after MRI were findings indicating a higher (n = 8) or lower (n = 5) local tumor stage, findings of para aortic nodal disease (n = 4) or difficulty to clinically examine the patient due to obesity (n = 2). MRI was also an aid in deciding whether or not to offer fertility preserving treatment in three cases. Conclusion. The use of MRI affects treatment planning in patients with cancer of the uterine cervix. The impact is more obvious in more advanced stages of disease and in patients who are difficult to examine clinically due to, for example body constitution. The result of MRI is also an aid in deciding whether or not a fertility preserving operation is feasible.

Carcinoma of the uterine cervix is globally the second most common tumor in women. More than 80% of cervical cancer cases occur in developing countries with 483 000 estimated new cases and 274 000 deaths yearly [Citation1]. The incidence in Sweden, as in many western countries, has decreased markedly after the introduction of cytological screening in the 1960s [Citation2]. Approximately 450 new cases are diagnosed in Sweden each year [Citation3].

The treatment of cervical carcinoma is largely dependent on tumor stage. The predominant tool in the staging procedure is the FIGO staging system from 1958 (www.figo.org), which is based upon clinical examination during anesthesia by an experienced examiner. The clinical stage according to FIGO is not changed because of subsequent imaging findings. When there is doubt as to which clinical stage a particular cancer should be allocated, the earlier stage is mandatory. The following examinations are permitted according to the FIGO rules: cystoscopy, proctoscopy, endocervical curettage, urography, barium enema and plain chest x-ray. The choice of treatment for each patient should traditionally be based upon the result of a gynecological examination under anesthesia, a cystoscopy, an examination to exclude hydronephrosis and plain chest x-ray. It is not permitted for the clinician to change the FIGO stage after imaging findings or surgery. It is just a complement to the FIGO stage and a support for the doctor to choose the appropriate treatment [Citation4].

Other staging systems (TNM, AJCC) have not gained the same acceptance and are not used in cervical cancer staging [Citation21].

Factors known to affect the prognosis include tumor size, lymphovascular space invasion, depth of stromal infiltration and histopathological features [Citation5]. The presence of lymph node metastases is not included in the FIGO-stage, although it affects the prognosis [Citation6,Citation7]. This leads to heterogeneity in survival within each FIGO-stage.

A large number of studies, both retrospective and prospective, have been made to assess whether the use of Computed Tomography (CT) and/or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) in addition to the FIGO classification improves evaluation of the extent of disease and if they can identify morphological risk factors of poor survival. The results have shown overall staging accuracies ranging between 75% and 90% not taking the study setup and particular risk factors into account [Citation8–10]. The staging accuracy of the FIGO system has been reported to be 50–80% with a tendency to be better in earlier stages than in more advanced stages [Citation11–15].

In 2003, MRI of the pelvis and abdomen was introduced at our unit as a routine part of the initial work-up for all patients with cervical carcinoma in addition to the standard FIGO examination in order to replace CT and urography. The reason was the need to improve pretreatment staging in accordance with published evidence in the literature supporting the use of MRI [Citation16,Citation17].

In this study, our aim was to assess the impact of MRI in the pretreatment planning of patients with cancer of the uterine cervix by retrospectively studying how MRI resulted in changes or modifications of the clinical management when performed in addition to the clinical diagnostic staging.

Material and methods

Study population

Patients with biopsy verified cervical carcinoma were referred from hospitals within the Stockholm region, with 1.8 million inhabitants, to the Department of Gynecological Oncology at Radiumhemmet, a tertiary regional referral centre. The study was accepted by the local ethics committee.

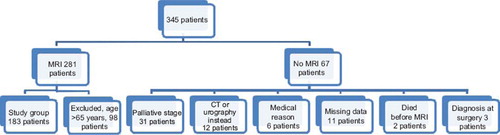

Of 345 patients diagnosed with cervical carcinoma between January 1, 2003 and December 31, 2006, 281 were examined with MRI. Sixty-seven patients did not undergo MRI due to reasons shown in .

Figure 1. Patient with cervical carcinoma diagnosed as IIa according to FIGO T2-weighted MR-images sagittal (a) and transaxial (b,c) shows a 3 cm tumour with (a,b) lobulated parametrial extensions (arrows) as well as (c) pelvic nodal metastases (arrows).

Since our aim was to study the influence of MRI on the choice of treatment, patients older than 65 years were excluded from the study group because of limited likelihood of hysterectomy due to probable comorbidities.

Thus, the material was reduced to 183 patients ().

Pretreatment examinations

MRI was performed using a 1, 5 T superconductive system (Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands). A phased array coil was used for signal reception. Sagittal and transverse T2-weighted images with 5 mm slice thickness covering the lesser pelvis were performed. In addition, T2-weighted oblique images parallel and perpendicular to the cervix were also obtained. A T1-weighted three dimensional refocused gradient-echo sequence with 2 mm slice thickness covering the pelvis was then obtained. The upper abdomen was examined using a T2-weighted sequence with 8 mm slice thickness. A fat saturated T1-weighted sequence of the upper abdomen was performed before and after i.v. administration of a Gadolinium chelate contrast agent in standard dosage. Finally, the examination was finished by repeating the three dimensional T1-weighted sequence of the pelvis, but this time using fat saturation.

Surgery, radiotherapy and follow-up

During the study period, the stage of the cancer was assigned according to FIGO. The result of the MRI was used together with FIGO to obtain an MRI/FIGO stage which was used for treatment planning. Patients with MRI/FIGO stage Ia1 disease were treated with either hysterectomy or radical cone biopsy. In MRI/FIGO stage Ia2, Ib1, Ib2 radical hysterectomy ad modum Wertheim Meigs was performed. In selected Ia2 or Ib1 cases, vaginal trachelectomy and laparoscopic pelvic lymphadenectomy was chosen as primary treatment. Patients with stage Ib1 tumors measuring more than 2 cm, stage Ib2 tumors or stage IIa tumors were treated with brachytherapy given with LDR/PDR (low-dose-rate/pulsed-dose-rate) technique on two separate occasions followed by surgery three weeks later. Patients found to have pelvic lymph node metastases at surgery and histopathological examination, were treated post operatively with radiochemotherapy. During the study period there was a shift in treatment of bulky stage Ib2 tumors from surgery to radiochemotherapy, given as a combination of external radiation and brachytherapy with weekly platinum-based, concurrent chemotherapy. The same regimen was used for the more advanced stages, i.e. stage IIb, III and IV. When para-aortic nodal disease was confirmed, additional radiation was given to the para-aortic region. Patients were followed at our department of gynecological oncology two to three times yearly during five years, and then transferred to their nearest gynecological outpatient clinic for yearly checkups. In the radiochemotherapy group the treatment effect was evaluated three months after the treatment was finished with a second MRI. Median follow up-time was 38 months (range 5–64) for patients treated with surgery and 27.5 months (range 0–59) for patients treated with radiochemotherapy.

Histopathology

The surgical specimen was examined by a board certified pathologist from paraffin-embedded hematoxyline-eosine stained thin slices. Each lymph node was sliced at 3 mm-intervals perpendicular to the greatest dimension to maximize the likelihood of detecting microscopic metastases. The original pathology report was used for the study.

Retrospective analysis

The records and histopathologic reports of 183 patients were retrospectively reviewed. Variables studied in the review were tumor stage according to FIGO, modes of treatment, tumor type according to the histopathological examination of the resected surgical specimen also including the number of removed lymph nodes, and lymph node metastases. Records were also analyzed for local and distant tumor recurrence, its time and means of diagnosis and also death and cause of death. If medical records revealed change or modification of therapy due to MRI-findings, this was noted.

Results

One-hundred and twenty-five (68%) patients were treated with surgery and 58 (32%) patients received radiochemotherapy. The different groups are shown in . Distribution of FIGO stages in the two treatment groups are shown in and the histopathological subgroups are shown in .

Table I. Distribution of stage in each treatment group.

Table II. Distribution of histopathological types in each treatment group.

Surgery group

Of the 125 patients, 116 patients underwent radical hysterectomy, six patients were treated with vaginal trachelectomy and laparoscopic pelvic lymphadenectomy, one patient with FIGO stage Ia1 was treated with ordinary hysterectomy, one patient underwent trachelectomy but refused the lymphadenectomy and one patient was treated in two separate sessions with first laparoscopic lymphadenectomy and then hysterectomy after a planned pregnancy.

Pretreatment group

Sixty seven of 125 patients were primarily operated. Of the remaining 58 patients who had pretreatment, 53 received brachytherapy, three patients had their brachytherapy interrupted because of complications (pulmonary embolus, uterine perforation and infection), one patient received cisplatinum and one patient received external radiotherapy as application of brachytherapy instruments was impossible due to large bulky tumors.

Pelvic nodal status

The number of dissected lymph nodes at surgery ranged between 5 and 59. For the Wertheim procedure, the mean number was 30 lymph nodes, for the laparoscopic operation the mean number of removed nodes was 12 (range 6–22). According to histopathology, 31 patients had lymph node metastases, 93 had no metastases and in one case no lymph node dissection was performed (see above). Fifty-two patients had different postoperative treatment as described above. Seventy-three patients did not receive any postoperative treatment.

Follow-up

In the surgery group, 21 patients (17%) developed recurrent disease; five had local recurrence, nine had distant metastases and seven had both.

Eighty-nine percent of the patients with recurrence were FIGO stage I and 52% had no pelvic lymph node metastases at the time of primary surgery. The number of removed lymph nodes in this group was ranging 15–46. Fifty-two percent were squamous cancers, 33% were adenocarcinomas and 14% were mucoepidermoid cancers.

Eight patients were lost at follow-up.

Two patients were diagnosed with a second cancer (breast and appendix, respectively) during follow-up.

Thirteen patients have died, all of them from recurrent cervical cancer.

How MRI results affected the treatment in the surgery group

In 10/125 cases, the medical records indicated that the result of the MRI investigation affected the planning of treatment. In 115 cases the impact of the results of the MRI on the decision making could not be established from the medical records. The tumor stage that the final treatment was based on was higher after MRI in five cases and lower in two cases. In three cases the clinical findings were initially equivocal and the patients did not receive their FIGO stage until after the MRI.

In three patients, the result of the MRI was important for the decision whether to do a radical hysterectomy or a vaginal trachelectomy. Two of these were attributed a lower tumor stage after MRI which contributed to make trachelectomy possible. One of these cases was in accordance with histopathology. In the other case, histopathology revealed a larger tumor than was suspected on the MRI. She is still in remission. The case that was treated for a higher tumor stage after MRI was in accordance with histopathology.

In summary, the change of tumor stage due to MRI when compared to histopathology correlated in six of seven cases. The one not correlating with histopathology was a tumor that was barely visible on MRI but examined by histopathology it was quite wide but thin and confined to the cervix. Two of the patients with the lower stage by MRI than FIGO (from IIb to Ib) died shortly after surgery from recurrent disease although histopathology indicated that the MRI stage was correct.

Radiochemotherapy group (RT)

Fifty-eight patients were treated with primary radiochemotherapy.

All 58 patients were treated with a combination of external radiation, brachytherapy and cisplatinum, except one who died before start of treatment. The MRI examination before treatment showed suspect parametrial involvement in 49 patients, suspect pelvic lymph node metastasis in 41 patients, para-aortic nodes in six patients and other nodal engagement (inguinal, mesorectal and in the liver hilum) in four patients.

How MRI results affected the treatment (RT)

In 12/58 patients, the medical records indicated that the result of the MRI affected treatment planning. Of these twelve, there were four cases where MRI showed enlarged para-aortic lymph nodes indicative of metastases. These received additional radiation to the para-aortic area. Two patients were obese which made clinical investigation very difficult. The results of the MRI played an important role in the treatment planning in these two patients. Six patients were treated according to a higher tumor stage after the MRI investigation. Two patients with FIGO stage Ib1, one with stage Ib2 and one with stage IIa () were found to have more advanced disease with parametrial involvement by MRI. In all those cases the previously decided plan for surgery was changed to radiochemotherapy. In two cases, the routine investigation under anesthesia was not performed because the tumor did not appear to be advanced at the ordinary gynecological examination. MRI, though, showed parametrial involvement in these two cases. In both cases a proper examination under anesthesia then was performed and, with that in mind, the patients were up-staged to IIb. The treatment plan was changed to radiochemotherapy. Since these patients were not treated surgically, we could not use histopathology as reference standard.

Follow-up

In the RT group, 23/58 patients have had recurrent disease, four patients still had viable tumor left after finished treatment and one patient had progressive disease during treatment. Thirty patients are in complete remission. Three patients have been diagnosed with a second cancer (one breast-, one head-neck-, one lung cancer) during follow-up. Twenty-five patients have died, 24 from cancer of the uterine cervix and one from head-neck cancer.

Discussion

This study shows that introducing MRI in pretreatment staging of CC affects both FIGO staging and treatment planning.

In our material, the impact of MRI seems to be greater in higher tumor stages, which is in accordance with previous studies indicating that FIGO alone as pretreatment staging works better in less advanced than in more advanced stages [Citation11–13].

It is hard to analyze the effect of MRI on treatment planning in a retrospective study when you have to rely on remarks in the patient's records. We only have proof when the doctor has made a clear note in the records. The extent of subconscious effect the MRI results may have had on the choice of treatment for a specific patient cannot be estimated. Höckel describes always having high resolution MRI series demonstrated when performing the FIGO investigation under anesthesia. It is described as an aid in deciding whether or not a tumor is resectable, especially when suspecting an advanced tumor [Citation18]. The North American multicenter study ACRIN 6651/GOG183 aiming to compare CT and MRI with FIGO examination and histopathology had to close prematurely before reaching the estimated number of cases. Instead of 440, only 208 patients could be included in the trial. The authors believe that increasing reliance on CT and MRI as part of the diagnostic work-up for cervical cancer staging was thought to be the main reason [Citation19].

In our study, there were three patients where the clinicians have actively chosen to wait until after MRI to allocate the patient to a FIGO stage. This is in conflict with the FIGO recommendations but in accordance with other observations. In the ACRIN 6651/GOG 183 study, an analysis showed that FIGO-prescribed diagnostic procedures were performed only in a minority of cases [Citation20]. Furthermore, in that study, MRI staging showed lower accuracy rates than in previous single centre studies while FIGO staging accuracies were surprisingly high compared to histopathology. The authors believe that this may be caused by the fact that 85% of the patients had undergone MRI and CT before the clinical examination and that the clinician then were influenced by the results of imaging.

One of the major difficulties in clinical staging is correct estimation of tumor size, especially when the growth is largely endocervical, another is assessment of parametrial or pelvic side wall involvement.

In our study, it was the tumor surgeons who took the initiative to change the treatment plan in agreement with the gynecological oncologist after MRI upstaging for the six patients originally planned for curative surgery. This may reflect the need for the surgeon to have access to a proper imaging before surgery and the fear of doing an unnecessary operation due to unresectable locally advanced disease [Citation21]. We do not know, though, if that was a good choice in these six cases since we don't have any histopathological results to compare with. The risk, however, to underestimate an advanced and non-resectable tumor is greater using only FIGO staging than with MRI assisted FIGO staging [Citation11–14,Citation21]. Our results are in accordance with those findings.

As age for the first pregnancy increases in the developed countries, the need for fertility preserving treatment methods for cervical carcinoma also increases. In 3/7 cases undergoing fertility preserving surgery, MRI was used to help the surgeon in this decision. In two of these three cases, the results of MRI and the decision of the preserving surgery was in accordance with histopathological verification.

For obese patients, an increasing problem in western healthcare, imaging plays a particularly important role since these patients are generally more difficult to examine clinically.

Para-aortic nodal involvement can be detected either by CT or MRI. In this study, six patients were treated with an additional radiation field over the aorta when MRI indicated para-aortic nodal involvement [Citation22].

Conclusion

Introduction of MRI in addition to the clinical staging of cancer of the uterine cervix affects both the clinical staging according to FIGO and the treatment planning. This is more obvious in more advanced stages. Our results also indicate that MRI plays an important role as a complement to clinical staging of cervical carcinoma in obese patients and in deciding fertility-preserving surgery in young patients.

Acknowledgements

Financial support was provided through the regional agreement on medical training and clinical research (ALF) between the Stockholm county council and the Karolinska Institutet. The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 2005;55:74–108.

- Bergström R, Sparén P, Adami HO. Trends in cancer of the cervix uteri in Sweden following cytological screening. Br J Cancer 1999;81:159–66.

- Cancer Incidence in Sweden 2007. Health and Diseases. The National Board of Health and Welfare; Stockhalm. 2008; 11.

- Benedet JL, Bender H, Jones H 3rd, Ngan HY, Pecorelli S. FIGO staging classifications and clinical practice guidelines in the management of gynecological cancers. FIGO committee on gynecologic oncology. Int J Gynecol Obst 2000 Aug;70(2):209–62.

- Delgado G, Bundy B, Zaino R, Sevin BU, Creasman WT, Major F. Prospective surgical-pathological study of disease-free interval in patients with stage IB squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol 1990;38:352–7.

- Pedullà F, Centurioni MG, Foglia G, Ferrari I, Orsatti M, Vitale V, . Treatment of FIGO stage Ib cervical carcinoma with nodal involvement. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 1994;15:59–64.

- Tinga DJ, Timmer PR, Bouma J, Aalders JG. Prognostic significance of single versus multiple lymph node metastases in cervical carcinoma stage IB. Gynecol Oncol 1990;39: 175–80.

- Chung HH, Kang SB, Cho JY, Kim JW, Park NH, Song YS, . Can preoperative MRI accurately evaluate nodal and parametrial invasion in early stage cervical cancer? Jpn J Clin Oncol 2007;37:370–5.

- Choi SH, Kim SH, Choi HJ, Park BK, Lee HJ. Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging staging of uterine cervical carcinoma: Results of a prospective study. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2004;28:620–7.

- Bipat S, Glas AS, van der Velden J, Zwinderman AH, Bossuyt PM, Stoker J. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of uterine cervical carcinoma: A systematic review. Gynecol Oncol 2003;91:59–66.

- Vidaurreta J, Bermúdez A, di Paola G, Sardi J. Laparoscopic staging in locally advanced cervical carcinoma: A new possible philosophy? Gynecol Oncol 1999;75:366–71.

- Lagasse LD, Creasman WT, Shingleton HM, Ford JH, Blessing JA. Results and complications of operative staging in cervical cancer: Experience of the Gynecology Oncology Group. Gynecol Oncol 1980;9:90–8.

- LaPolla JP, Schlaerth JB, Gaddis O, Morrow CP. The influence of surgical staging on the evaluation and treatment of patients with cervical carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 1986; 24:194–206.

- Mitchell DG, Snyder B, Coakley F, Reinhold C, Thomas G, Amendola M, . Early invasive cervical cancer: Tumor delineation by magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, and clinical examination, verified by pathologic results, in the ACRIN 6651/GOG 183 Intergroup Study. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:5687–94.

- Van Nagell JR Jr, Roddick JW Jr, Lowin DM. The staging of cervical cancer: Inevitable discrepancies between clinical staging and pathologic findings. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1971;110:973–8.

- Hricak H, Lacey CG, Sandles LG. Invasive cervical carcinoma: Comparison of MR imaging and surgical findings. Radiology 1988;166:623–31.

- Subak LL, Hricak H, Powell CB. Cervical carcinoma: Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging for preoperative staging. Obstet Gynecol 1995;86:43–50.

- Höckel M. Ultra-radical compartmentalized surgery in gynaecological oncology. Eur J Surg Oncol 2006;32:859–65.

- Hricak H, Gatsonis C, Chi DS, Amendola MA, Brandt K, Schwartz LH, . Role of imaging in pretreatment evaluation of early invasive cervical cancer: Results of the intergroup study American College of Radiology Imaging Network 6651 – Gynecologic Oncology Group 183. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:9329–37.

- Amendola MA, Hricak H, Mitchell DG, Snyder B, Chi DS, Long HJ III, . Utilization of diagnostic studies in the pretreatment evaluation of invasive cervical cancer in the United States: Results of Intergroup Protocol ACRIN 6651/GOG 183. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:7454–9.

- Narayan K. Arguments for a magnetic resonance imaging-assisted FIGO staging system for cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2005;15:573–82.

- Whitney CW, Stehman FB. The abandoned radical hysterectomy: A Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Gynecol Oncol 2000;79:350–6.