Abstract

During the last decades, the possibilities to prolong survival with chemotherapy even in metastatic disease have increased. Our aim was to study treatment decisions and treatment discontinuation decisions in the proximity of death. Methods. The medical records of 346 patients with disseminated cancer and a recorded death during 2009 were assessed in relation to demographic and clinical variables and documented treatment decisions were recorded. Results. Palliative chemotherapy was offered in 54% or these cases and generally one or two regimens were administered, before ending treatment. During the last month of life, 32% received treatment and much more often as an oral (instead of intravenous) treatment than in earlier stages (p < 0.001). Younger patients (p = 0.02) and those with young children (p < 0.001) were treated to a higher degree and also closer to death (p = 0.03). Other variables associated with a higher probability of treatment were high education level (p = 0.001), living with a partner (p = 0.001), female gender (p = 0.023) and ethnicity of non-European origin (p = 0.031). In a multivariate analysis, young age and high education remained as independent factors. In 57% of the cases there was no formal documentation of treatment discontinuation or end-of-life discussions with the patient. Conclusion. Socioeconomic status (SES) is of importance for the treatment decisions. About half of the patients with disseminated disease receive palliative chemotherapy and of these, about one third are treated even during the last month of life. In a majority of cases, there is no formal documentation of treatment discontinuation or end-of-life discussions.

In recent years, the therapeutic options for palliative cancer patients have increased, mostly due to more effective chemotherapy regimens and the introduction of targeted therapies, i.e. medications that block the growth of cancer cells by interfering with specific targeted molecules needed for carcinogenesis and tumor growth [Citation1,Citation2]. In oncological settings, the palliative phase starts when there are no further possibilities for cure, but the focus is on life prolongation and symptom control. This phase can vary from weeks and months to several years, depending on the primary diagnosis and the metastatic pattern. An increasing proportion of cancer patients in the palliative phase receive oncological treatment and, as a result, the overall survival has increased [Citation3,Citation4]. In 2030, the estimated cancer prevalence in Sweden is doubled compared to today [Citation5], a significant number of cancer patients being in the palliative phase.

In previous studies [Citation6,Citation7], the number of patients receiving palliative chemotherapy during the last month of life varies greatly (9–43%). The main stated reasons for palliative chemotherapy are hopes of prolongation of life, however, survival is difficult to predict [Citation8] and doctors tend to overestimate survival by far [Citation9]. Other goals are improvement of quality of life and reduction of common symptoms such as pain, bleeding and dyspnea.

There is a perception that palliative chemotherapy treatment is used too generously to cancer patients in the terminal phase, with no obvious indications [Citation8,Citation10,Citation11]. The patients are at risk of spending too much time receiving treatments in the terminal phase with no or minimal benefits and disturbing side effects may reduce quality of life. Moreover, active treatment may also produce false hopes of an extended life, thus impairing the patient's opportunities to prepare for his or her own death and hampering his or her chances to receive an appropriate level of palliative care [Citation12,Citation13].

Despite detailed information, patients and families may have unrealistic expectations and may request oncologic treatment, also in the absence of medical indications. Moreover, patients are often willing to undergo treatment even when the probability of benefit is low and the risk of toxicity is high [Citation14,Citation15]. Additional reasons for possible overtreatments are the physician's inability to communicate and break bad news. Instead, it might be easier to continue treatment on the patient's request, even in desolate cases [Citation16].

Since over-treatment is perceived as a problem in the palliative phase, the aim of the study was to investigate how chemotherapy is prescribed at the end-of-life to patients treated at the Department of Oncology at the Karolinska University Hospital in Stockholm. Initiation of palliative chemotherapy was analyzed with regard to clinical and demographic factors. Documentation of underlying treatment decisions, as well as documentation about decisions to end treatment, was studied.

Methods

This study was conducted as a single center retrospective cohort study at the Department of Oncology at the Karolinska University Hospital. This oncology department comprises of three different units in the greater Stockholm area and serves the county of Stockholm with a population of about two million inhabitants.

The Regional Oncology Center in Stockholm-Gotland helped us identify all patients who had died during 2009 and who had at least one entry in the computerized medical record system generated at the Karolinska Hospital Oncology Department during the same period. Manual search identified patients who had died during the months of April and November, resulting in 424 patients. These patients were followed from their first contact with the Oncology Department until their death. Most of these patients were seen regularly by medical staff at one of the oncology clinics. In some cases there was only documentation of distant consultations or discussions at multidisciplinary conferences. Some patients were treated by specialists in other fields, such as lung medicine or hematology, but a written consultation was made to the oncology department. Patients with benign diagnoses, as well as patients treated with a curative intent who died from other reasons than a disseminated cancer were excluded, resulting in a cohort of 346 patients ().

Table I. Patients included in the study. Initially, 424 patients who had at least one entry in the computerized medical record system at the Oncology Department were screened. Patients who were not eligible for different reasons were excluded, resulting in 346 study patients.

The medical records were reviewed as regards to demographic, clinical and treatment-related data. Patients were described as having received chemotherapy if they had received chemotherapy, targeted treatment or a combination of both.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics such as mean averages, median and proportions were used to describe the data.

Group differences were analyzed using Students t-test, and if the assumption of normal distribution was not met, we used Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis tests. Differences in proportions were analyzed using χ2-test. Multiple logistic regression was performed to determine whether chemotherapy treatment was independently associated with gender, age, education, marital status, presence of under-aged children in the family and/or to ethnicity.

The study was approved by the regional ethics committee (2010/711-31/1).

Results

The mean age for the whole cohort was 68.6 years (range 20–100 years): it was 62.6 years versus 75.2 years for those who were treated/not treated with chemotherapy (p = 0.02). Other demographic and clinical data are summarized in .

Table II. Cancer diagnoses relation to given chemotherapy. In the cohort of 346 patients (Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden 2009), a total of 187 received treatment.

Proportion of treated patients

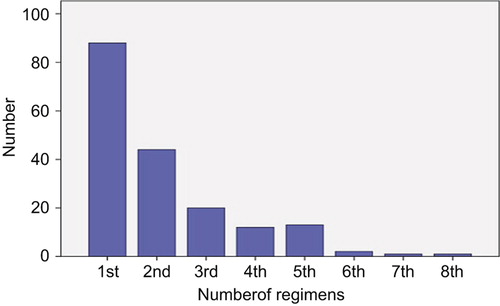

Of the 346 patients in the cohort, 54% received palliative chemotherapy and/or targeted treatment, of which 73% were only considered eligible for first or second line of chemotherapy (). Patients with chemo-sensitive tumors, such as breast- or ovarian cancer, were more likely to receive additional lines of treatment, up to eight regimens (data not shown).

Figure 1. The number of specified chemotherapy regimens. Most of the patients received only first-line and second-line palliative chemotherapy.

Young patients (p = 0.02), especially those with young children (p < 0.001), received chemotherapy to a higher degree than others. Other statistically significant variables for chemotherapy treatment were female gender (p = 0.023), high level of education (p < 0.001), cohabitation/being married (p < 0.001) and non-European origin (p = 0.031). Distance to the oncology department and type of residential area (metropolitan, urban or rural) had no relationship to the initiation of chemotherapy treatment.

However, only educational level and patient age remained significant after multiple regression analysis (). The odds ratio was 3.7 for education. As regards to age (analyzed as a continuous variable), the odds ratio was 1.3 for each five years and 1.6 for each 10 years, respectively.

Table III. Odds ratio for different variables. Age and education remained significant variables in the multiple logistic regression analysis.

Treatment decisions

According to the reviewed patient charts, the treatments were primarily given with a life-prolonging intent, whereas the goal to alleviate symptoms was a secondary aim, but never the only reason for new treatment regimens. In 97% of cases, treatment decisions were based on a combination of recent clinical and radiographic evaluations. In the remaining 3%, the decision was based on an evident clinical picture of tumor progress. Likewise, there was usually clinical and radiographic evidence of disease progression to support the decision to end chemotherapy. In 18% of cases side effects were the main cause for ending treatment.

In 43% of patient records, there was a documented decision to end chemotherapy treatment and documentation of an end-of-life discussion with the patient.

Closeness to death

On the average, there were 82 days (median 46 days) between the last administration of chemotherapy and death. In total, 32% of those patients ever considered eligible for palliative chemotherapy treatments received chemotherapy also during the last 30 days of their lives. Patients were eligible for such treatment, if they were judged to have any further chance of achieving a life prolongation or symptom reduction, and provided that there were no medical contra-indications, such as a poor performance score or signs of bone marrow failure. In these relatively terminal cases oral, in contrast to intravenous, treatment was administered to a higher degree during the last month of life, compared to earlier in the course (46% during the last month of life, 19% during earlier phases) (p < 0.001). When oral treatment was chosen, capecitabin was the most commonly used drug (24%), followed by cyclophosphamide (20%), erlotinib (13%) and etoposide (13%), as single drugs or in combinations.

Young patients with children under the age of 18 were those who received chemotherapy closest to death (p = 0.03).

Most patients (94%) died an expected death. Ten deaths were treatment-related, six of which related to a failure of the bone marrow. The majority of deaths (77%) occurred either in palliative care units (45%) or within advanced palliative home care service with 24 hour home care availability (32%). Of those who died at an acute hospital, 10 of 33 deaths were due to treatment complications, the others died from other reasons.

Discussion

A number of studies from different countries have indicated differences in cancer treatment decisions, related to socioeconomic status (SES) [Citation17–19]. Even outcome is affected, with shorter survival for low-SES patients [Citation18–20]. In our study, univariate analyses showed that palliative chemotherapy treatment was significantly more commonly administered if the patient was well-educated, young, had under-aged children, was married or cohabiting or was of non-European origin. In multivariate analysis age and educational level remained as significant factors. This is well in line with recent studies where young age and high education have been associated with more intensive treatment efforts [Citation18–20].

As regards age, there might be both rational and emotional reasons for the treatment decisions. Frailty as a biological entity, with inflammation, reduced muscle mass and hormonal changes, is well-described within geriatric research [Citation21] and the oncologist might hesitate to treat such patients. Older patients are in general more fragile and have reduced physiological reserves as regards renal function and circulation and they are more likely to suffer from disturbing side effects than younger patients.

Emotionally, it is easy to understand that an oncologist prescribes palliative chemotherapy more often to a young treatment-prone patient with minor children, even when there is an obvious lack of scientific evidence. This was also obvious in a recent interview study: the wishes of the treatment-prone patients, i.e. those who are very eager to receive treatment, are difficult to resist [Citation22]. In such situations, empathy, sympathy, as well as ‘emotional contagiation’ and compassion may play role. Compassion is defined to involve ‘the affective feeling for caring for a suffering person, and the motivation to relieve the other person's suffering’ [Citation23]. Also psychodynamic defence mechanisms, e.g. identification or projective identification may play a role. Projective identification means that the patient transfers his negative feelings and anxiety to the physician, who strongly feels these emotions in him- or herself. Such strong experiences may partly be explained by new knowledge about so called mirror neurons. Mirror neurons are being discussed as a possible reason for our empathic and emotional response to our co-fellows’ suffering [Citation24,Citation25].

As regards educational level, highly educated patients are well-informed and they may have searched the web and may even confront the oncologist with specific treatment suggestions. Moreover, the physician may feel more at ease with a well- educated person as they partly have the same background. At the same time the physician may feel more confident with their ability to observe and report side effects. This has been labeled concordance in the patient-physician relationship [Citation26].

Cohabitation or being married increased the likelihood to receive treatment (univariate analysis), which was not unexpected, as previous studies have shown that living with a partner can even reduce cancer mortality [Citation27,Citation28], probably due to earlier detection and more intense treatment. Moreover, the physician may feel safer prescribing chemotherapy to a person living with a partner, as the partner is likely to report if the patient develops severe side effects.

In contrast to several other studies [Citation29,Citation30], ethnicity of non-European origin was associated with a higher, not lower, probability of receiving palliative chemotherapy. The reasons are unclear, but as Swedish healthcare is tax-financed and available to all citizens at nominal cost, other factors are probably more important. As a basic driving force is to please patients and relatives, and as patients of non-European origin often are accompanied by several relatives, the oncologist is probably tempted to give in for wishes from the family (unpublished qualitative interview data). Another possible explanation is the difference in the communication and in breaking bad news to a patient and his family from immigrant cultures, with language barriers and different and sometimes unrealistic expectations [Citation31].

As a disappointing finding, there were documentation of ending treatment in only 43% of the cases, thus it remains unclear whether the remaining 57% of the patients were offered end-of-life discussions at all, or whether they just had a disease progression, cancelled their appointment and were never really offered an appointment for discussion of their impending death and palliative care planning.

Whether this finding only reflects incomplete documentation or an avoidance to discuss dying and death, cannot be decided from the data, even if other studies indicate that breaking bad news is stressful for the doctors and therefore, they might be reluctant to address the issue [Citation32–34].

About 32% received palliative chemotherapy during their last month of life and mainly as oral treatment, which can be compared to figures between 9% and 46% in other international studies [Citation8,Citation11]. In Swedish conditions, Näppä et al. showed that 23% of the patients in the northern part of Sweden were treated [Citation7]. However, in our study only 54% received palliative chemotherapy at all, in the other cases the patient was either considered not to benefit from treatment at all (46%), or were prescribed hormonal (25%) or palliative radiotherapy (44%) treatment.

In the mentioned study by Näppä et al., those who were treated with chemotherapy even close to death, died more often at an acute hospital [Citation7]. This was not the case in our study.

In conclusion, socioeconomic status seems to influence palliative treatment decisions near end-of-life. Less than 50% of patients receive documented end- of-life discussions, which is a remarkably low figure.

Declaration of interest: The author report no conflicts of interest. The author alone is responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

The study was supported by the Swedish Cancer Society (Cancerfonden) and by Stockholm County Council (PickUp grants).

References

- Bergh J. Quo vadis with targeted drugs in the 21st century? J Clin Oncol 2009;27:2–5.

- Hudis CA. Trastuzumab – mechanism of action and use in clinical practice. N Engl J Med 2007;357:39–51.

- Andre F, Slimane K, Bachelot T, Dunant A, Namer M, Barrelier A, et al. Breast cancer with synchronous metastases: Trends in survival during a 14-year period. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:3302–8.

- Renouf D, Kennecke H, Gill S. Trends in chemotherapy utilization for colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2008;7:386–9.

- Cancerfonden. Cancerfondsrapporten (Swe). Stockholm: The Swedish Cancer Society; 2011. pp. 132.

- Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, Ayanian JZ, Block SD, Weeks JC. Trends in the aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:315–21.

- Nappa U, Lindqvist O, Rasmussen BH, Axelsson B. Palliative chemotherapy during the last month of life. Ann Oncol 2011;22:2375–80.

- Emanuel EJ, Young-Xu Y, Levinsky NG, Gazelle G, Saynina O, Ash AS. Chemotherapy use among Medicare beneficiaries at the end of life. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:639–43.

- Christakis NA, Lamont EB. Extent and determinants of error in doctors’ prognoses in terminally ill patients: Prospective cohort study. BMJ 2000;320:469–72.

- Harrington SE, Smith TJ. The role of chemotherapy at the end of life: “When is enough, enough?” JAMA 2008;299:2667–78.

- Murillo JR, Jr., Koeller J. Chemotherapy given near the end of life by community oncologists for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Oncologist 2006;11:1095–9.

- Browner I, Carducci MA. Palliative chemotherapy: Historical perspective, applications, and controversies. Semin Oncol 2005;32:145–55.

- Chochinov HM, Tataryn DJ, Wilson KG, Ennis M, Lander S. Prognostic awareness and the terminally ill. Psychosomatics 2000;41:500–4.

- Chu DT, Kim SW, Kuo HP, Ozacar R, Salajka F, Krishnamurthy S, et al. Patient attitudes towards chemotherapy as assessed by patient versus physician: A prospective observational study in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2007;56:433–43.

- Matsuyama R, Reddy S, Smith TJ. Why do patients choose chemotherapy near the end of life? A review of the perspective of those facing death from cancer. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:3490–6.

- Saviani-Zeoti F, Petean EB. Breaking bad news: Doctors’ feelings and behaviors. Span J Psychol 2007;10:380–7.

- Bernheim SM, Ross JS, Krumholz HM, Bradley EH. Influence of patients’ socioeconomic status on clinical management decisions: A qualitative study. Ann Fam Med 2008;6:53–9.

- Byers TE, Wolf HJ, Bauer KR, Bolick-Aldrich S, Chen VW, Finch JL, et al. The impact of socioeconomic status on survival after cancer in the United States: Findings from the National Program of Cancer Registries Patterns of Care Study. Cancer 2008;113:582–91.

- Cavalli-Bjorkman N, Lambe M, Eaker S, Sandin F, Glimelius B. Differences according to educational level in the management and survival of colorectal cancer in Sweden. Eur J Cancer 2011;47:1398–406.

- Albano JD, Ward E, Jemal A, Anderson R, Cokkinides VE, Murray T, et al. Cancer mortality in the United States by education level and race. J Natl Cancer Inst 2007;99: 1384–94.

- Walston J, Hadley EC, Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Newman AB, Studenski SA, et al. Research agenda for frailty in older adults: Toward a better understanding of physiology and etiology: Summary from the American Geriatrics Society/National Institute on Aging Research Conference on Frailty in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54:991–1001.

- Cavalli-Bjorkman N, Glimelius B, Strang P. Equal cancer treatment regardless of education level and family support? A qualitative study of oncologists’ decision-making. BMJ Open 2012;2:e001248.

- Singer T. The past, present and future of social neuroscience: A European perspective. Neuroimage 2012;61:437–49.

- Dapretto M, Davies MS, Pfeifer JH, Scott AA, Sigman M, Bookheimer SY, et al. Understanding emotions in others: Mirror neuron dysfunction in children with autism spectrum disorders. Nat Neurosci 2006;9:28–30.

- Rizzolatti G. The mirror neuron system and its function in humans. Anat Embryol (Berl) 2005;210:419–21.

- Street RL, Jr., O’Malley KJ, Cooper LA, Haidet P. Understanding concordance in patient-physician relationships: Personal and ethnic dimensions of shared identity. Ann Fam Med 2008;6:198–205.

- Chang SM, Barker FG, 2nd. Marital status, treatment, and survival in patients with glioblastoma multiforme: A population based study. Cancer 2005;104:1975–84.

- Pinquart M, Duberstein PR. Associations of social networks with cancer mortality: A meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2010;75:122–37.

- Bhargava A, Du XL. Racial and socioeconomic disparities in adjuvant chemotherapy for older women with lymph node-positive, operable breast cancer. Cancer 2009;115: 2999–3008.

- Obeidat NA, Pradel FG, Zuckerman IH, Trovato JA, Palumbo FB, DeLisle S, et al. Racial/ethnic and age disparities in chemotherapy selection for colorectal cancer. Am J Manag Care 2010;16:515–22.

- Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, Finkelman MD, Mack JW, Keating NL, et al. Patients’ expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1616–25.

- Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, Tulsky JA, Fryer-Edwards K. Approaching difficult communication tasks in oncology. CA Cancer J Clin 2005;55:164–77.

- Baider L, Wein S. Reality and fugues in physicians facing death: Confrontation, coping, and adaptation at the bedside. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2001;40:97–103.

- Ptacek JT, Eberhardt TL. Breaking bad news. A review of the literature. JAMA 1996;276:496–502.