Abstract

Background. Fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) or cancer progression is one of the most frequent distressing psychological symptoms in cancer patients. In contrast to anxiety disorders according to the ICD-10 or DSM-IV, FCR describes an emotional response to the real threat of a life-threatening illness. Elevated levels of FCR can become dysfunctional, causing considerable disruption in social functioning, and affect well-being and quality of life (QoL). We examined the prevalence and course of FCR in cancer patients during and after a rehabilitation program, and investigated associations between demographic, medical and psychosocial factors. We further aimed to identify predictors of FCR one year after cancer rehabilitation. Methods. A total of eligible N = 1281 patients (77.5% participation rate) were consecutively recruited on average 11 months post-diagnosis and assessed at the beginning (t1) (1148), at the end (t2) (1060) and 12 months after rehabilitation (t3) (n = 883). Participants completed validated measures assessing FCR, anxiety, depression, QoL, social support, and a range of cancer- and treatment-related characteristics. Results. At t1, 18.1% of our sample was classified as having high levels of FCR and 66.6% showed moderate levels of FCR. Fear of recurrence decreased over time (p < 0.001) (η² = .095), however, at follow-up 17.2% of our sample showed high levels of FCR and 67.6% had moderate levels of FCR. Linear regression analysis (stepwise backward) including demographic, medical and psychosocial factors, revealed that lower social class, having skin cancer, colon cancer or hematological cancer, palliative treatment intention, pain and a higher number of physical symptoms, depression, lower social support and adverse social interactions predicted FCR one year after rehabilitation (R² adjusted = 0.34) (p < 0.001). Conclusion. Our data provide evidence that elevated levels of FCR represent a continuing problem in cancer patients. The need to enhance cancer rehabilitation and survivorship programs including interventions tailored to specific problems such as FCR is emphasized.

Fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) is one the most frequent distressing symptoms in cancer patients [Citation1,Citation2]. While anxiety disorders based on structured psychiatric interviews according to the DSM-IV and ICD-10 have a prevalence of averagely 10% in cancer populations [Citation3,Citation4], cancer-related worries and concerns about disease recurrence or progression were found in 24% up to 70% of cancer patients [Citation5–14]. Some studies have also shown frequent unmet supportive care needs concerning FCR [Citation15–17]. Patients reported particularly moderate to high unmet needs including needing help with fear of cancer spreading, and uncertainty about the future [Citation18].

Fear of cancer recurrence (or fear of cancer progression) describes a common form of subjective distress, often involving fears related to the cancer itself, to recurrence and metastasis, to follow-up care and periodic examinations, to relying on strangers for activities of daily living as well as to worry about the future life, disability or death [Citation8,Citation19–21]. It has been a particularly useful concept in cancer patients and the seriously medically ill. In contrast to anxiety disorders according to the ICD-10 or DSM-IV, FCR describes an appropriate and rational response to the real threat of a cancer diagnosis and invasive treatments [Citation20,Citation22]. However, elevated levels of FCR can become dysfunctional, causing considerable disruption in concentration, decision-making, sleep, and social functioning, and affect well-being and quality of life [Citation1,Citation8,Citation20,Citation23].

In a variety of cancer populations such as head and neck cancer and breast cancer patients, FCR has been associated with younger age [Citation11,Citation13,Citation24], having children [Citation8,Citation25], higher levels of physical symptom burden and neurotoxic treatment effects [Citation9,Citation26], advanced tumor stage [Citation11], elevated levels of (trait) anxiety [Citation7,Citation11,Citation13,Citation24,Citation27] lower social support, family stressors and fewer significant others [Citation11,Citation26], low optimism, low self-efficacy and low self-esteem [Citation7,Citation9,Citation25,Citation26]. Studies have also shown that FCR was higher in patients with elevated levels of mental distress including mental disorders, fatigue, neuroticism and cancer-related post-traumatic stress symptoms such as intrusive cognitions [Citation8–10]. However, Crist and Grunfeld indicate that particularly inconsistent results were found with regard to the influence of socio-demographic, medical or treatment-related factors on FCR [Citation7,Citation9,Citation13,Citation26]. Furthermore, there is mixed evidence for the course of FCR over the cancer trajectory, with one study showing a decline in FCR over time [Citation25], and other studies reporting stable levels of FCR [Citation13,Citation28].

Given the limited number of prospective studies focusing on FCR in cancer survivors, more studies are necessary to investigate the long-term course and predictors of FCR in this group, as well as their impact on quality of life (QoL) [Citation29]. Since comprehensive cancer rehabilitation and survivorship care programs can play an important role in identifying and addressing FCR [Citation30], thus, the purpose of this study was examine the prevalence and course of FCR in cancer patients during and after a rehabilitation program, and to investigate associations between demographic, medical and psychosocial factors and FCR particularly taking into account physical symptom burden. Furthermore, we aimed to identify predictors of FCR one year after cancer rehabilitation. The following research questions were addressed in detail:

1. What proportion of cancer patients show low, moderate and high levels of FCR?

2. What are the demographic, cancer- and treatment-related as well as psychosocial factors significantly related with FCR at the beginning of the cancer rehabilitation program?

3. Does FCR decline significantly over time between the beginning of the cancer rehabilitation and one year follow-up?

4. What are demographic, cancer- and treatment-related and psychosocial factors that predict FCR one year after cancer rehabilitation?

Methods

Participants

This study was part of a larger prospective study investigating psychosocial and occupational burden in cancer patients using a prospective multicenter research design including three assessment points. Participants were consecutively recruited from four cancer rehabilitation clinics and were assessed at the beginning of cancer rehabilitation (t1), at the end of cancer rehabilitation (t2) and at one-year follow-up (t3). In Germany, a three-week rehabilitation program is offered to cancer patients to regain physical and psychosocial functioning. The access is usually facilitated by hospital doctors and social workers. A typical cancer rehabilitation program includes patient education, exercises for physical fitness and vitality, relaxation training, psychosocial support to enhance coping skills as well as individual counseling.

The study received research ethics committee approval in all involved federal states. All patients provided written informed consent prior to participation. Subject inclusion criteria contained the evidence of a malignant tumor, age between 18 and 60 years, the capability to complete a battery of self-report measures, and the absence of permanent general and occupational invalidity, disablement and early retirement. Subject exclusion criteria included the presence of severe cognitive and/or verbal impairments that would interfere with a patient's ability to give informed consent for research. All patients who agreed to participate completed a set of standardized self-report questionnaires. Patients who declined to participate voluntarily provided information about reasons for non-participation, age, gender, and cancer site.

A total of 1281 patients of 1653 were enrolled at t1 (77.5% participation rate); 372 patients declined to participate. The most frequent reasons for non-participation were lack of interest (36%), distress (31%), physical burden (7%), as well as several other reasons (26%). Among those who participated at t1, 1193 (93.1%) completed the questionnaires at t2. One year after rehabilitation (t3), questionnaires were mailed to eligible 1127 cancer patients (36 patients had moved to an unknown address and 30 had died). Evaluable questionnaires were returned by N = 883 patients (68.9%) (). presents baseline sample characteristics.

Figure 1. Enrollment of patients (t1 = beginning of cancer rehabilitation, t2 = end of cancer rehabilitation, t3 = 12 months after cancer rehabilitation).

Table I. Demographic and medical sample characteristics at the beginning of the cancer rehabilitation (t1) (N = 883).

Non-participation analyses

At t1 participants were significantly younger (M = 48.5, SD = 7.2 vs. M = 50.4, SD = 6.1) (p < 0.001) (d = 0.3) and more likely to be female (p = 0.007) (ϕ = 0.07) compared to non-participants. No group differences in cancer entities were observed.

Dropout analyses

Compared to t2, at t3, non-participating patients were more likely to be male (p = 0.008) (ϕ = 0.09), widowed (p = 0.03) (ϕ = 0.10), and to have head and neck or lung cancer (p = 0.005) (ϕ = 0.14). Participants at t3 were found to be significantly less depressive (p = 0.01) (η² = 0.007) and had a lower level of fear of cancer recurrence at t2 (p = 0.009) (η² = 0.007). Dropout analyses comparing t1 and t3 showed no further significant differences.

Measures

Sociodemographic data including age, gender, marital status and partnership, were assessed via patients self-report. Education, household net income and occupational position were used to calculate a three-factor social status index [Citation31]. Medical information was collected at baseline [cancer entity, months since diagnosis, Union Internationale Contre le Cancer (UICC) cancer stage, clinical characteristics and disease phase]. In addition to the Karnofsky performance status physicians estimated the degree of functional impairment using cancer entity specific physical functioning scales [Citation32]. Pain intensity during the last week was evaluated on a scale ranging from 0 (‘no pain’) to 10 (‘worst pain imaginable’) using the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) [Citation33].

FCR was measured using the short version of the Fear of Progression Questionnaire (FoP-Q-SF) [Citation34], a 12-item measure based on the Fear of Progression Questionnaire (FoP-Q) [Citation20]. The questionnaire has a high internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.87). The FoP-Q-SF items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (‘never’) to 5 (‘very often’), higher values indicating higher levels of fear of recurrence. Typical items address concerns such as “being nervous prior to doctors’ appointments or periodic examinations” or “being afraid of severe medical treatments in course of the illness”. For the classification of low, moderate and high levels of FCR, we used the cutoff value based on the mean value ± 1 SD.

Anxiety and depression was assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [Citation35]. Distress was measured using the German version of the NCCN Distress-Thermometer [Citation36], which consists of a visual analog scale, the thermometer, ranging from 0 to 10 and a problem list. The problem list covers the presence of physical (20 items), emotional (5 items), family (2 items), practical (5 items), as well as spiritual problems (2 items).

The Short-Form Health Survey assesses eight dimensions of QoL: Here, the two summary scores for physical (PCS) and mental health (MCS) were calculated; higher scores indicating better QoL [Citation37]. The Illness-specific Social Support Scale (ISSS) measures positive support and adverse, detrimental social interaction. Detrimental aspects of social relationships in this measure include over-protective behavior, dismissive, conflictual behavior patterns, and pessimism. Items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (‘never‘) to 4 (‘always‘) [Citation38].

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 18.0. To answer research question one, we used a statistical approach (mean value ± 1 SD) to determine a cutoff for low, moderate and high FCR. This approach was chosen in absence of a valid external criterion, since this problem applies to most current dimensional scales measuring FCR [Citation29]. To answer research question two, group differences were calculated using analysis of variance (ANOVA) (gender, marital status, partnership, social class, cancer entity, cancer stage, clinical characteristics, disease and treatment phase). Bivariate associations between variables were calculated using Pearson's Product-Moment correlation coefficient (pain, age, time since diagnosis, anxiety, depression, social support, detrimental social interactions, physical and mental health).

To answer research question three, we used repeated measures analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA) with time as within-subjects factor with two levels (t1–t3). In addition, group differences (between-subject-factors) were tested for significance including gender, partnership, social class, cancer entity, cancer stage, clinical characteristics, disease and treatment phase). To answer research question four, linear regression analysis (stepwise backward) was carried out. We chose backward elimination, because it tests each candidate variable for removal using Wald statistic within the model containing all candidates, and permanently eliminates the variable with the highest p-value among those above a prespecified retention criterion. Forward selection risks stopping too early when linear combinations of remaining candidate variables retain predictive power that the individual variables do not [Citation39].

Results

Prevalence of FCR

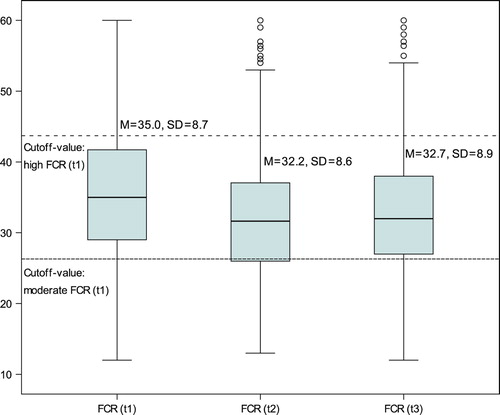

At t1, the total mean score on the Fear of Cancer Recurrence scale was M = 35.0 (SD = 8.7) (range 12–60); at t2, the total mean score was M = 32.2 (SD = 8.6) (range 13–60); and at t3, the total mean score was M = 32.7 (SD = 8.9) (range 12–60). Using the cutoff value based on the mean value (± 1 SD), at t1 135 patients (15.3%) were classified as having low FCR, 588 patients (66.6%) were classified as having moderate FCR, and 160 patients (18.1%) were classified as having high FCR. At t2 132 patients (14.9%) were classified as having low FCR, 607 patients (68.7%) were classified as having moderate FCR, and 144 patients (16.3%) were classified as having high FCR. At t3 134 patients (15.2%) were classified as having low FCR, 597 patients (67.6%) were classified as having moderate FCR, and 152 patients (17.2%) were classified as having high FCR. We identified 54 patients (6.1%) with low FCR and 64 patients (7.2%) with high FCR at all assessment points.

Factors associated with FCR

Higher FCR was associated with female gender (p < 0.001), being widowed (p < 0.001), lower social class (p < 0.02), lung cancer (p < 0.001), cancer recurrence or progress (p = 0.02) as well as palliative treatment intention (p = 0.01); however, effect sizes were small (). Furthermore, pain was significantly associated with FCR (r = 0.38) (p < 0.001). Age (p = 0.34) and time since diagnosis (p = 0.28) were not correlated with FCR. Significant positive correlations were found between FCR and anxiety (r = 0.65) (p < 0.001), depression (r = 0.54) (p < 0.001), and detrimental social interactions (r = 0.37) (p < 0.001). Significant negative correlations were found between FCR and physical health (r = 20.27) (p < 0.001), mental health (r = 20.53) (p < 0.001), and social support (r = 20.16) (p < 0.001).

Course of FCR

Patients improved significantly over time in FCR (p < 0.001) with a moderate effect size (η² = 0.095) (). No interaction effects with demographic variables including gender, partnership, social class (p-values > 0.26) and medical characteristics including cancer entity, cancer stage, clinical characteristics, disease and treatment phase (p-values > 0.16) were found.

Predictors of FCR

Linear regression analysis was conducted in order to identify the variance in FCR at follow-up accounted for by demographic, medical and psychosocial factors measured at t1. Based on the significant correlational results between candidate predictor and FCR (t3) shown in , intercorrelations among the predictor variables were calculated. In candidate predictor variables with intercorrelations of r > 0.60, the variable with a lower correlation with the outcome variable was removed from the linear regression analysis in order to avoid multicollinearity. Thus, baseline anxiety (HADS) and both mental and physical QoL (SF-8) were removed. In step one, demographic factors accounted for 2% of the variance in FCR (p < 0.001). In step two, demographic and medical factors accounted for 28% of the variance in FCR (p < 0.001) and in step three, together with psychosocial factors they accounted for 34% of the variance (p < 0.001). Overall, the following variables remained in the final model: social class, skin cancer, colon cancer and hematological cancers, treatment intention, pain, number of physical symptoms, depression, social support and detrimental interactions (R² adjusted = 0.34) (p < 0.001).

Table II. Hierarchical linear regression analysis of fear of recurrence at follow-up (t3) (N = 883).

Discussion

Our results indicate that at the beginning of a cancer rehabilitation program, averagely 11 months post-diagnosis, 18% of our samples were classified as having high levels of FCR and 67% showed moderate levels of FCR. One year after the rehabilitation program 17% of our sample showed high levels of FCR and 68% had moderate levels of FCR. Thus, we found slightly lower levels of FCR compared with previous research [Citation5–14], although studies frequently did not distinguish between moderate and high levels of FCR. The fact that slightly more than two thirds of our sample experience moderate levels of FCR emphasizes the importance of specific interventions addressing FCR. For example, Herschbach et al. developed an effective brief cognitive-behavioral psychotherapeutic group intervention to reduce fear of progression and cancer recurrence [Citation3,Citation40–42].

Although in our study the mean value of FCR decreased significantly over time; our findings however suggest that a relatively large number of patients report persistent fears of recurrence during the first two years after cancer diagnosis. This result was underlined by the fact that FCR was not associated with time since the cancer diagnosis. Similar findings have been shown by Hodgkinson et al. [Citation43] and others [Citation13,Citation28,Citation44]. The reduction of FCR before and after rehabilitation can be discussed as a possible effect of the rehabilitation program which offers a range of evidence-based psychological interventions to reduce overall mental distress in cancer patients. Given the pre-post study design and the lack of randomization including a control group, however, the methodological limitations of the study design do not allow conclusions about the efficacy of the rehabilitation program to specifically reduce FCR. On the other hand, our findings can also not be interpreted as originating from a traditional observational study, since we cannot preclude that the rehabilitation program would have an effect on reducing FCR.

In our heterogeneous sample of cancer patients, elevated levels of FCR were significantly associated with having lung cancer, cancer recurrence or progress, palliative care treatment intention and pain. Although literature reviews showed inconsistent results about the effect of cancer- and treatment-related factors on FCR [Citation9,Citation11,Citation26], our findings strengthen the notion that increased levels of FCR are at least partially subjective emotional responses caused by a poorer prognosis and a real threat to a patient's life [Citation20]. In addition, in a study by McGinty et al. [Citation45] in early breast cancer survivors, findings indicated that threat appraisal but not coping appraisal was related to FCR.

In accordance with previous studies, we found FCR associated with anxiety, depression and detrimental social interactions as well as lower QoL and social support [Citation7,Citation9–11,Citation13,Citation24,Citation27]. Our study, furthermore, shows that lower social class, skin, colon and hematological cancers, palliative treatment intention, a higher number of physical symptoms and pain, depression, lower social support and higher detrimental interactions significantly predict FCR one year after cancer rehabilitation explaining 34% of the variance. The result of the regression analysis could suggest that disease progression including lower physical functioning and pain, combined with adverse social environments (such as lower education and lower income) and detrimental social interactions are particular risk factors for higher FCR.

Our prospective study was methodologically strong with regard to the inclusion of a consecutive sample, a satisfactory response rate of 77.5% (t1) and 68.9% (t2) a relatively large sample size and the use of a variety of validated measures. However, there are several limitations that should be considered. There is repeated evidence to suggest that respondents who cease to participate in prospective studies differ from participants in both their better health status and their sociodemographic characteristics including higher education. The findings of this study are limited to patients participating in cancer rehabilitation programs. Given the annual cancer incidence of 490 000 cases in Germany, approximately about one third (152 000 patients) take part in a cancer rehabilitation program per year [Citation46]. Data about demographic, medical and psychosocial characteristics of non-participants compared to participants in cancer rehabilitation programs are not available; however, a participation bias cannot be ruled out.

With regard to the generality and interpretation of the findings, it also has to be considered that our study excluded patients older than 60 years and those with permanent invalidity, disablement and early retirement. Both the initial and the follow-up non-response lead to a bias in several sociodemographic and psychosocial outcome variables of interest in this research such as FCR. Thus, a sample bias towards female gender, younger age, and cancer sites associated with a better physical health status and prognosis as well as lower FCR and depression has to be considered. Our findings might underestimate the occurrence and severity of FCR. Nevertheless, systematic differences between participants and non-participants were small in view of effect sizes and at least partially a consequence of the relatively large sample size. In addition to the possible sample bias, we lacked information about the psychological status and particularly FCR of participants before admission to the rehabilitation program.

Although the Fear of Progression Questionnaire (FoP-Q-SF) [Citation34] is a validated measure with excellent internal consistency, a clinical cutoff-value has not been established so far to distinguish lower and higher levels for FCR. We therefore used a statistical approach to determine cutoff values for the classification of low, moderate and high levels of FCR. Further research is needed to address this critical issue by properly determine an accurate cutoff-value from a clinical perspective.

Our data provide evidence that elevated levels of FCR represent an important and continuing problem in cancer. Fear of cancer progression and recurrence should be addressed during the rehabilitation and follow-up care. The need to develop and enhance cancer rehabilitation within cancer survivorship programs including interventions tailored to specific problems such as FCR has been already emphasized [Citation30,Citation47,Citation48].

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

This research was funded by the Nordrhein- Westfalen Association for the Fight Against Cancer and Paracelsus-Kliniken Deutschland GmbH, Germany.

References

- Koch L, Jansen L, Brenner H, Arndt V. Fear of recurrence and disease progression in long-term (≥ 5 years) cancer survivors – a systematic review of quantitative studies. Psycho-Oncology 2013;22:1–11.

- Handschel J, Naujoks C, Kubler NR, Kruskemper G. Fear of recurrence significantly influences quality of life in oral cancer patients. Oral Oncol 2012;48:1276–80.

- Herschbach P, Berg P, Waadt S, Duran G, Engst-Hastreiter U, Henrich G, et al. Group psychotherapy of dysfunctional fear of progression in patients with chronic arthritis or cancer. Psychother Psychosom Psychother Psychosom 2010;79:31–8.

- Vehling S, Koch U, Ladehoff N, Schön G, Wegscheider K, Heckl U, et al. Prevalence of affective and anxiety disorders in cancer: Systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol 2012;62:249–58.

- Deimling GT, Bowman KF, Sterns S, Wagner LJ, Kahana B. Cancer-related health worries and psychological distress among older adult, long-term cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology 2006;15:306–20.

- van den Beuken-van Everdingen MHJ, Peters ML, Rijke JM de, Schouten HC, van Kleef M, Patijn J. Concerns of former breast cancer patients about disease recurrence: A validation and prevalence study. Psycho-Oncology 2008;17:1137–45.

- Llewellyn CD, Weinman J, McGurk M, Humphris G. Can we predict which head and neck cancer survivors develop fears of recurrence? J Psychosom Res 2008;65:525–32.

- Mehnert A, Berg P, Henrich G, Herschbach P. Fear of cancer progression and cancer-related intrusive cognitions in breast cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology 2009;18:1273–80.

- Skaali T, Fossa S, Bremnes R, Dahl O, Haaland CF, Hauge ER, et al. Fear of recurrence in long-term testicular cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology 2009;18:580–8.

- Pedersen AF, Rossen P, Olesen F, Maase H, Vedsted P. Fear of recurrence and causal attributions in long-term survivors of testicular cancer. Psycho-Oncology Epub 2011 Aug 25.

- Liu Y, Pérez M, Schootman M, Aft RL, Gillanders WE, Jeffe DB. Correlates of fear of cancer recurrence in women with ductal carcinoma in situ and early invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011;130:165–73.

- Petzel MQB, Parker NH, Valentine AD, Simard S, Nogueras-Gonzalez GM, Lee JE, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence after curative pancreatectomy: A cross-sectional study in survivors of pancreatic and periampullary tumors. Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:4078–84.

- Ghazali N, Cadwallader E, Lowe D, Humphris G, Ozakinci G, Rogers SN. Fear of recurrence among head and neck cancer survivors: Longitudinal trends. Psycho-Oncology Epub 2012 Mar 27.

- Thewes B, Butow P, Bell ML, Beith J, Stuart-Harris R, Grossi M, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence in young women with a history of early-stage breast cancer: A cross-sectional study of prevalence and association with health behaviours. Support Care Cancer 2012;20:2651–9.

- Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Fuchs A, Hunt GE, Stenlake A, Hobbs KM, et al. Long-term survival from gynecologic cancer: Psychosocial outcomes, supportive care needs and positive outcomes. Gynecol Oncol 2007;104:381–9.

- Schmid-Buchi S, Halfens RJG, Dassen T, van den Borne B. A review of psychosocial needs of breast-cancer patients and their relatives. J Clin Nurs 2008;17:2895–909.

- Armes J, Crowe M, Colbourne L, Morgan H, Murrells T, Oakley C, et al. Patients’ supportive care needs beyond the end of cancer treatment: A prospective, longitudinal survey. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:6172–9.

- Beesley V, Eakin E, Steginga S, Aitken J, Dunn J, Battistutta D. Unmet needs of gynaecological cancer survivors: Implications for developing community support services. Psycho-Oncology 2008;17:392–400.

- Stark DP, House A. Anxiety in cancer patients. Br J Cancer 2000;83:1261–7.

- Herschbach P, Berg P, Dankert A, Duran G, Engst-Hastreiter U, Waadt S, et al. Fear of progression in chronic diseases: Psychometric properties of the Fear of Progression Questionnaire. J Psychosom Res 2005;58:505–11.

- Hirai K, Shiozaki M, Motooka H, Arai H, Koyama A, Inui H, et al. Discrimination between worry and anxiety among cancer patients: Development of a brief cancer-related worry inventory. Psycho-Oncology 2008;17:1172–9.

- Simard S, Savard J, Ivers H. Fear of cancer recurrence: Specific profiles and nature of intrusive thoughts. J Cancer Surviv 2010;4:361–71.

- Hart S, Latini D, Cowan J, Carroll P. Fear of recurrence, treatment satisfaction, and quality of life after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Support Care Cancer 2008;16:161–9.

- Ziner KW, Sledge GW, Bell CJ, Johns S, Miller KD, Champion VL. Predicting fear of breast cancer recurrence and self-efficacy in survivors by age at diagnosis. Oncol Nurs Forum 2012;39:287–95.

- Melchior H, Büscher C, Thorenz A, Grochocka A, Koch U, Watzke B. Self-efficacy and fear of cancer progression during the year following diagnosis of breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology 2013;22:39–45.

- Crist JV, Grunfeld EA. Factors reported to influence fear of recurrence in cancer patients: A systematic review. Psycho-Oncology Epub 2012 Jun 3.

- Shim E, Shin Y, Oh D, Hahm B. Increased fear of progression in cancer patients with recurrence. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2010;32:169–75.

- Ernst J, Peuker M, Schwarz R, Fischbeck S, Beutel ME. Long-term survival of adult cancer patients from a psychosomatic perspective – literature review and consequences for future research. Z Psychosom Med Psychother 2009;55:365–81.

- Thewes B, Butow P, Zachariae R, Christensen S, Simard S, Gotay C. Fear of cancer recurrence: A systematic literature review of self-report measures. Psycho-Oncology 2012;21:571–87.

- Mikkelsen TH, Sondergaard J, Jensen AB, Olesen F. Cancer rehabilitation: Psychosocial rehabilitation needs after discharge from hospital? Scand J Prim Health Care 2008;26:216–21.

- Winkler J, Stolzenberg H. Der Sozialschichtindex im Bundesgesundheitssurvey. Gesundheitswesen 1999;61:S178–83.

- Karnofsky DA, Burchenal JH. The clinical evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents in cancer. In: MacLeod C, editor. Evaluation of Chemotherapeutic Agents: Columbia University Press; 1949. p 196.

- Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: Global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore 1994;23:129–38.

- Mehnert A, Herschbach P, Berg P, Henrich G, Koch U. Progredienzangst bei Brustkrebspatientinnen – Validierung der Kurzform des Progredienzangstfragebogens PA-F-KF. Z Psychosom Med Psychother 2006;52:274–88.

- Herrmann C, Buss U, Snaith R. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale - Deutsche Version (HADS-D). Manual: Hans Huber; 1995.

- Mehnert A, Müller D, Lehmann C, Koch U. Die deutsche Version des NCCN Distress-Thermometers - Empirische Prüfung eines Screening-Instruments zur Erfassung psychosozialer Belastung bei Krebspatienten. Z Psychiatr Psychol Psychother 2006;54:213–23.

- Ware JE, Kosinski M, Dewey JE, Gandek B. How to score and interpret single-item health status measures: A manual for users of the SF-8TM Health Survey. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated; 1999.

- Ullrich A, Mehnert A. Psychometrische Evaluation and Validierung einer 8-Item Kurzversion der Skalen zur Sozialen Unterstützung bei Krankheit (SSUK) bei Krebspatienten. Klin Diagnostik u Evaluation 2010;3:359–81.

- Imrey PB. Poisson regression, logistic regression, and loglinear models for random counts. In: Tinsley HEA, Brown SD, editors. Handbook of applied multivariate statistics and mathematical modeling. New York: Academic Press; 2000. p391–437.

- Herschbach P, Book K, Dinkel A, Berg P, Waadt S, Duran G, et al. Evaluation of two group therapies to reduce fear of progression in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2010; 18:471–9.

- Sabariego C, Brach M, Herschbach P, Berg P, Stucki G. Cost-effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral group therapy for dysfunctional fear of progression in cancer patients. Eur J Health Econ 2011;12:489–97.

- Dinkel A, Herschbach P, Berg P, Waadt S, Duran G, Engst-Hastreiter U, et al. Determinants of long-term response to group therapy for dysfunctional fear of progression in chronic diseases. Behav Med 2012;38:1–5.

- Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Hunt GE, Pendlebury S, Hobbs KM, Wain G. Breast cancer survivors’ supportive care needs 2–10 years after diagnosis. Support Care Cancer 2007;15: 515–23.

- Sekse RJT, Raaheim M, Blaaka G, Gjengedal E. Life beyond cancer: Women's experiences 5 years after treatment for gynaecological cancer. Scand J Caring Sci 2010;24:799–807.

- McGinty HL, Goldenberg JL, Jacobsen PB. Relationship of threat appraisal with coping appraisal to fear of cancer recurrence in breast cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology 2012;21: 203–10.

- German Pension Insurance (Ed). Rentenversicherung in Zahlen 2012, Statistik der Deutschen Rentenversicherung, 2012. [cited 2012 Dec 09]. Available from: http://www.deutsche-rentenversicherung.de/cae/servlet/contentblob/238692/publicationFile/51912/rv_in_zahlen_2012.pdf

- Mehnert A, Harter M, Koch U. Long-term effects of cancer. Aftercare and rehabilitation requirements. Bundesgesundhbl Gesundheitsforsch Gesundheitsschutz 2012;55:509–15.

- Ewertz M, Jensen A. Late effects of breast cancer treatment and potentials for rehabilitation. Acta Oncol 2011;50:187–93.