Abstract

Introduction. In this study, we present data from a population-based cohort of incident cancer patients separated in long- and short-term survivors. Our aim was to procure denominators for use in the planning of rehabilitation and palliative care programs. Material and methods. A registry-linkage cohort study. All cancer patients, diagnosed from 1993 to 2003 from a 470 000 large population, were followed individually from diagnosis to death or until 31 December 2008. Long-term survivors lived five years or more after the time of the cancer diagnosis (TOCD). Short-term survivors died less than five years after TOCD. Results. The cohort comprised 24 162 incident cancer patients with 41% long-term survivors (N = 9813). Seventy percent of the cohort was 60 + years at TOCD. The 14 349 short-term survivors’ median survival was 0.6 year, and 78% died less than two years after TOCD. A 12 years’ difference in age at TOCD was seen between long- and short-term survivors, with median ages of 60 versus 72 years, respectively. Females comprised 64% of long-term, and 46% of short-term survivors. The proportion of breast and lung cancers differed between the groups: Long-term survivors: 31% breast cancer, 2.4% lung cancer. Short-term survivors: 21% lung cancer, 7.2% breast cancer. Chemotherapy was provided to 15% of all patients, and to 10% of the 60 + year olds. Discussion. The epidemiology of long- and short-term survivors shows significant differences with regard to age at TOCD, cancer types and sex. Two-year crude cancer survival seems as a clinically relevant cut point for characterizing potential “denominators” for rehabilitation or palliative care programs. From this cohort of incident cancer patients, and using two-year survival as a cut point, it could be estimated that 54% would candidate to a “care trajectory” focusing on rehabilitation and 46% a “care trajectory” focusing on palliative care at TOCD.

Focus on the optimization of health care to cancer patients during the trajectories of their diseases has increased. The importance of rehabilitation and palliation has been addressed in several studies. Concerning the patients’ needs and expectations, a substantial and increasing amount of literature exists, but population-based data on the proportions and demography of patients, who may become users of these initiatives, are very sparse. When healthcare services are planned, it is important to know the target populations [Citation1], and factors like the expected number of participants, their age, cancer type and sex [Citation2]. Difficulties in finding published survival data from unselected cancer populations may explain, why “needs for cancer care” in the healthcare systems’ seem to rely on estimates from relative survival of specific cancer types [Citation3], cancer mortality [Citation4] and prevalence [Citation2]. In terms of the society's health care planning, the relevance and validity of forecasts based on these epidemiological constructs can, however, be questioned [Citation5].

Even though both rehabilitation and palliation have been defined by WHO, there is still a lack of definitional clarity that hampers the efforts to standardize and improve the cancer care, with regard to organization, in daily clinical work and in research [Citation6,Citation7]. A clinically relevant grouping of the patients could help to clarify characteristics of the target populations for rehabilitation and/or palliation, and to improve the estimations of demands for cancer care programs.

In a prior population-based cohort study [Citation8], we noticed that 75% of those patients, who died less than five years after the time of the cancer diagnosis (TOCD) actually died during the first two years after TOCD. The same was observed in a study of place of death, where most of the deaths occurred within two years of registration [Citation9]. We also noticed a significant difference in age at TOCD between cancer patients, who survived or did not survive five years after the cancer diagnosis [Citation8]. The observations led us to consider, if most incident cancer patients actually enter one of two “generic” trajectories for cancer care, one trajectory for long-term survivors and another for short-term survivors. In one trajectory, treatment would aim for cure, and rehabilitation programs should be targeted and tailored with this in mind. In the other trajectory, treatment would aim for prolongation of life and/or increased quality of life, and palliative care programs should be offered to these patients. The importance of a conceptual framework for palliative care has very recently been pointed out by Bruera and Hui [Citation10]. So, despite the lack of definitional consensus with regard to rehabilitation or palliative care interventions [Citation7], this study attempts to challenge the idea of two generic trajectories for care to newly diagnosed cancer patients, and to suggest a useful framework for estimation of needs and organization of cancer health care, as proposed by Lynn J, in her book “Sick To Death and Not Going to Take It Anymore!” [Citation11].

Five-year survival (i.e. the percentage of patients alive five years after the time of the diagnosis) has been the traditional epidemiological measure of cancer survival, and the term “survivor” was prior commonly restricted to persons with cancer, who remained disease free for a minimum of five years [Citation12]. Lately, this definition has been challenged, so in this paper, patients are referred to either as long-term survivors, if they live longer than five years, or short-term survivors, if they live less than five years after TOCD. The study aims to provide a population-based overview of the epidemiology of cancer long- and short-term survivors. Factors like age at TOCD, cancer type, sex, survival and provision of chemotherapy, are presented with the aim of characterizing target populations for rehabilitation or palliative care.

Method

This is a population-based, retrospective cohort study using linkage between comprehensive registries, where each individual is followed from the cancer diagnosis to death or for five years or more. The cancer cohort was identified from a background population of 470 000 inhabitants. Several epidemiological studies have used this population, which covers 9% of the total Danish population and is considered to be representative for the whole country [Citation13,Citation14].

Databases

Individual data on the patients were obtained by linkage between three existing population-based databases; the Danish Cancer Register [Citation15], Odense Pharmaco-epidemiological Database [Citation16], OPED, and a database keeping information of chemotherapy provided to all cancer patients in the population. The identifier in all three databases was the CPR number, a unique personal identification number, provided to every citizen in Denmark, and registered in the Civil Registration System. The Danish Cancer Register has for all practical purposes full coverage of the Danish cancer population, dating back to 1942 [Citation15]. The register provides information on each cancer case with CPR number, anatomic site and histological classification according to ICD-10, month and year of the diagnosis, and date of death. In this study, the date of diagnosis was defined as the 15th of the month of the diagnosis. Unfortunately the validity of the stage at TOCD in the database is too insufficient to be included as an explanatory variable. By use of a demographic module in OPED, holding information on all citizens in the region including dates of migration and deaths, the linkage procedure with the Cancer Register enabled identification of all patients in the county with a diagnosis of invasive cancer. Only incident cancer patients, who were inhabitants in the county from TOCD and until death or 31 December 2008, were included in the analyses. Even though prior studies in this population have shown that potential migration problems concern less than 5% of the patients in the cohort [Citation17]. Patients, who were candidates for chemotherapy, were all referred to the Oncology Department, Odense University Hospital, except for very few patients with renal cell cancer or malignant melanoma, who received immunotherapy. Since 1992, the department has kept a database with individualized data on the type of chemotherapy, dosages, and dates provided to the patients. The database is considered valid and comprehensive, since chemotherapy cannot be prepared and administered without registration in the database. In this study, we only included a yes/no variable for the provision of chemotherapy. Data on chemotherapy were included partly by convenience, but also because it is considered to be of interest in the planning of care programs to know if the patients have received chemotherapy.

Patient cohort

All patients diagnosed with cancer for the first time during 1993–2003, were identified. The patients were followed from the date of the cancer diagnosis until death or the 31 December 2008. Patients with common skin cancer as the only cancer diagnosis were not included. Patients were classified as short-term survivors, if they died less than five years after the cancer diagnosis. Long-term survivors were patients, who were alive five years or longer after the date of the diagnosis. Prior to the analyses of the cohort, the patients were divided in three sub-cohorts, based on the calendar year of the diagnosis, “1993–1995”, “1996–1999”, and “2000–2003”. This was to decide if the patients could be treated as one cohort, or if it would be more appropriate to stratify according to time of entrance, due to the 11-years’ long inclusion period.

The cohort was categorized in three groups according to age at TOCD; below 40 years, 40–59 years, and 60 years+, based on the following considerations: For patients younger than 40 years, the composition of cancer types and histopathology differ compared to older patients. Patients younger than 60 were expected to return to the labor market if successfully treated for their cancer [Citation18]. The pension age in Denmark is 65, but we assumed that a larger proportion of patients at the age of 60 years or older at TOCD would retire from the labor market after the cancer treatment had finished [Citation19].

Cancer types

The patients’ cancer types are registered in the Cancer Registry according to ICD-10. Using the ICD-10 coding, the patients were categorized in seven major groups of cancer type, when the proportions according to the three age intervals were described. This was a compromise between simplicity of the overview, and specificity regarding the most frequent cancer types. In the characterization of age at TOCD according to survival status, 14 groups were presented to render comparisons with other cohorts of specified cancer types more feasible.

Results

The cohort included 24 162 patients diagnosed with cancer during the 11-year period, 1993–2003. The overall five-year survival was 40.6%, and 7311 of the 9813 long-term survivors were still alive at the end of the observation period, 31 December 2008. The 14 349 short-term survivors had a median/mean observation time from diagnosis and until death of 0.6/1.14 years respectively, and 78% of the short-term survivors died less than two years after the diagnosis. From the perspective of the whole cohort, these figures imply that 30% of all the patients died less than 7.2 months after TOCD and 46% died less than two years after TOCD.

Age

shows the proportions of patients in the three age intervals, where 69% of the whole cohort were 60 years or older at TOCD. Among long- and short-term survivors, the older patients comprised 51% and 81%, respectively. Only 2% of the short-term survivors and 13% of the long-term survivors were younger than 40 years at TOCD.

Table I. Proportions (%) of long- and short-term cancer survivors, in three age intervals, and according to the most frequent cancer types.

The median age at TOCD was 60 years for the long-term survivors and 72 years for the short-term survivors ().

Table II. Median age at the time of the cancer diagnosis for long- and short-term survivors, 2- and 5-years crude survival, and percentages of short-term survivors, who died less than 2 years after TOCD.

To illustrate the overall observation, that for all cancer types, the median age was considerably lower for long-term survivors compared to short-term survivors, the differences in age at diagnosis are shown in , where the cancer types are ranked according to long-term survivors’ age at TOCD.

Figure 1. Age at the time of the cancer diagnosis for long- and short-term survivors.

Oth-fem-gen, other female genital; oth_GI/liver, gastrointestinal cancer other than colorectal cancer; undef_prim, undefined primary cancers.

The largest difference in age at diagnosis was seen for patients with cervical cancer, and patients in the group of “other” cancers displayed the second largest difference.

Age at TOCD and age at death during the 11-years inclusion period

The median and mean age at TOCD, 60/58 years for long-term survivors and 72/70 years for short-term survivors, remained unchanged in all three sub-cohorts generated according to calendar year of the diagnosis, “1993–1995” (N = 2506), “1996–1999” (N = 3445) and “2000–2003” (N = 3862). The median age at death remained unchanged at 73 years in all three cohorts. The mean age at death increased to 72 years in the “2000–2003” cohort from 71 years in the two preceding cohorts “1993–1995” and “1996–1999”. Based on these observations, we found no reason to stratify the patients in the cohort according to the calendar year of their cancer diagnosis.

Cancer types

Breast cancer was, by far, the most frequent cancer type among long-term survivors, comprising 31%. Among short-term survivors, breast cancer only comprised 7%. For lung cancer, the opposite picture was seen, where 2.4% of the long-term survivors and 21% of the short-term survivors had lung cancer. The group of “other” cancer types comprised 35% of long-term survivors and 39% of short-term survivors. For patients younger than 40 years at diagnosis, their cancer types should mostly be found in the “other” group.

In , the listing of two- and five-years crude survival and the proportions of short-term survivors, who die less than two years after TOCD, provides a more detailed picture of the different cancer types’ survival pattern.

Sex

Overall, 53% of the incident cancer patients were females (N = 12 836), with 64% females in the long-term survivors’ group and 46% in the short-term survivors’ group. The proportions of females overall, and among patients with “other” cancer types, are shown in italic in . Females comprised 72% in the group of long-term survivors aged 40–59 years, this was explained by the large number of patients with breast cancer, cervical cancer and other female cancer types. A small overweight of men was observed among short-term survivors older than 40 years at TOCD.

Proportions of patients receiving chemotherapy

Fifteen percent of the incident cancer patients received chemotherapy (), 16% of long-term survivors and 14% of short-term survivors. Ten percent of patients older than 60 years received chemotherapy, this applied to both long- and short-term survivors. The largest proportion was observed in the numerically small group of young short- term survivors (N = 279), where 47% had received chemotherapy sometime during their trajectory.

Discussion

In this population-based cohort of incident cancer patients 41% became long-term survivors, i.e. they survived more than five years after the diagnosis, and 46% survived less than two years. We argue that these two groups of cancer patients have different needs with regard to rehabilitation and palliative care. At TOCD, future long-term survivors are likely to present a cancer type and disease stage, where the prognostic and predictive variables justify a treatment plan with curative intent. Rehabilitation should be offered to these patients. In the healthcare system's planning of rehabilitation programs it should be taken into consideration that the majority of long-term survivors seem to be persons either treated for less frequent cancer types (here 35%) or women treated for breast cancer (here 31%), and with half of the patients being in the working age. For short-term survivors it should be acknowledged that a substantial proportion survive less than two years. In fact, half of the short-term survivors in our cohort survived less than seven months after TOCD. Patients surviving less than two years will most likely present with advanced or metastatic cancer, and have symptoms from their cancer. The short survival time in advanced cancer has been recognized in several studies [Citation10,Citation20]. Palliative care programs must be provided to these patients and their relatives by the healthcare system, irrespective of concomitant antineoplastic treatment. In our cohort, 13% of the patients survived from two to five years after TOCD. They could be termed medium-term survivors. At TOCD, their cancer type and disease stage would most likely predict an equivocal prognosis, but their performance status and comorbidity would allow for a curative treatment plan or more intensive palliative antineoplastic therapy [Citation4], with the hope of cure or significant prolongation of survival. Therefore, it seems appropriate to include the proportion of medium-term survivors in the estimations of need for rehabilitation programs. Service planning for cancer care has been addressed in several recent publications [Citation1,Citation21]. So far, the planning seems to have relied on the assumption that each cancer patient experience five main phases on the care pathway [Citation22]; 1) diagnosis and treatment; 2) rehabilitation; 3) monitoring for recurrence, and then the pathway splits in two, either 4a) survival or 4b) progressive illness; and 5) “end of life”. Judged by the survival observed in our population, a large proportion (46%) continued directly from phase 1 to phase 4b and 5, and an equally large proportion (41%) would most likely never enter into phase 4b [Citation23]. So, when long- term survivors reach phase 5, the large majority will be as persons, who once were cured from cancer. Therefore, we suggest that the healthcare systems’ need for cancer rehabilitation and palliative care programs rely on “denominator-populations” of incident cancer patients characterized by their two- and five-years’ crude survival and their epidemiology, combined with knowledge of patients’ needs in relation to the different cancer types and their treatment. As documented in a recent, nationwide patient survey, many cancer patients experience unmet needs of care, related to both sociodemographic and clinical factors [Citation24]. So far, relative survival, cancer mortality and occasionally cancer prevalence have been the preferred basis for estimations of needs for care. Relative survival in age-adjusted populations is an epidemiological construct made for comparisons between countries or areas. Small differences that might appear negligible on first view in some of the assumptions for estimated survival may lead to severe overestimation of long-term relative survival, especially for very long-term follow-up periods and for older age groups [Citation5]. Cancer mortality data has been used as a proxy for the number of people requiring end of life care [Citation4,Citation22]. Cancer mortality data do not take into account, how long time prior to death, the patients were diagnosed with cancer. Using the prevalent cancer population for estimations of care needs [Citation2], can also prove problematic. The cohort of prevalent cancer patients mainly consists of long-term cancer survivors, and its epidemiology will differ from the incident cancer population, both with regard to proportions of cancer types, age and sex. In the recent literature, forecasting of “cancer care needs” has mainly relied on data from specific cancer types’ or selected patient groups, and not from population-based, unselected cancer populations. This is possibly explained by the difficulties in finding published data on cancer crude survival for unselected cancer populations (including all patients with invasive cancers except common skin cancer). In a publication by Higginson [Citation25] the overall five-year survival from cancer was mentioned to lie between 50% and 60% in high-income countries, but no references were listed. In the publication by Lichtenfeld [Citation21], the five-year survival in USA was said to approach 67%, but we were not able to find this percentage in the referred text. Even in the CONCORD-study by Coleman et al., survival data were not available on the level of whole populations, but they were presented according to tumor type [Citation3]. We identified only two sources of survival data for whole populations, the NORDCAN database [Citation26] and the SEER statistics from USA [Citation27]. They provided age-standardized, relative survival and not crude survival, and as demonstrated by Brenner [Citation5] this can result in severe overestimation of long-term survival.

In our cohort, long- and short-term survivors differed with regard to age at TOCD, frequency of different cancer types and sex. Long-term survivors were considerably younger than short-term survivors at TOCD, a general trait for all the different cancer types. This difference in age is likely to have multifactorial explanations, but it supports the hypothesis that treatment intensity is higher to young compared to old patients with the same type of cancer. It is suggestive that in our cohort, only 10% of patients older than 60 years received chemotherapy, compared to around 25% of those younger than 60 years, regardless of survivor status. Comorbidity might be an explanation of the seemingly small proportion of older patients receiving chemotherapy. However, population-based data on cancer patients’ use of chemotherapy are very sparse. Therefore, it is difficult to judge whether our figures of use of chemotherapy are comparable to, or deviant from, other cancer populations. When cancer care programs are planned, the proportion of patients exposed to chemotherapy should be considered. Chemotherapy was found to be a strong predictor for participation in an inpatient rehabilitation program for breast cancer patients [Citation28]. However, it is not known, whether treatment with chemotherapy can be regarded as a general predictor for the need for rehabilitation.

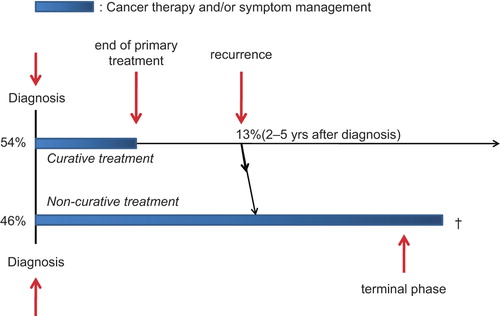

Based on our results and clinical experience we propose a model of two generic trajectories for cancer care to be applied on the cohort of incident cancer patients ().

Figure 3. Two generic trajectories for cancer care to enter for newly diagnosed cancer patients. The model of two generic trajectories for cancer care, with the numbers from our cohort applied. At the time of the cancer diagnosis, 54% (cohort’s 2-years survival) of the patients would enter the “rehabilitation trajectory” and 46% (100–2-years survival) the “palliative care” trajectory. Within 2–5 years, 13% (2–5 year survival) of patients would then have to move from the rehabilitation to the palliative care trajectory, most likely due to recurrence. Rehabilitation programs should target patients in the upper trajectory. Palliative care initiatives, either alone or concomitant with cancer treatment, should target patients in the lower trajectory.

This concept adds to ongoing discussions of “cancer survivors”, “cancer survivorship” and the advantages and disadvantages in this labeling of cancer patients [Citation29]. The concept of “survivorship” was defined by The National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship (NCCS), a cancer advocacy group founded in 1986. NCCS defined cancer survivorship as “the experience of living with, through, and beyond a diagnosis of cancer”. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) based their definition of survivorship on NCCS's definition, as “the phase that follows primary treatment and lasts until cancer recurrence or end of life” [Citation30] in their report; “From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition”. Using the survival data in our cohort, 54% of the patients seemed to fit well with this definition, but 46% never seemed to go “beyond a diagnosis of cancer”. If we neglect these facts, a large proportion of cancer patients could risk to be “lost in comprehension” instead of “lost in transition”, with delayed institution of palliative care! We find it of importance to acknowledge and implement this in the healthcare systems’ planning and dimensioning of rehabilitation and palliative care programs. There are common elements in both rehabilitation and palliation, such as symptom management, emotional support, appropriate dietary and exercise interventions, and family support. However, palliative care programs should emphasize conversations regarding advanced care planning, end of life care including place of death, and discontinuation of active cancer treatment, while in rehabilitation programs emphasis should be on other aspects such as improving function, employment, and prevention of long-term complications and secondary malignancies.

Our study has certain limitations. Valid population-based data on cancer stage at TOCD, comorbidity, or treatment schedules including radiotherapy were not available. These data could have enhanced the ability to categorize the patients with regard to their possible needs for rehabilitation or palliative care programs. Nor did we know the quality of life or perceived needs for rehabilitation or palliative care among patients and relatives. In a cross sectional study of 1490 Danish cancer patients’ perceived needs for rehabilitation [Citation31], 39% did not receive the physical rehabilitation they felt they needed, and 10–24% reported that other rehabilitation offers were insufficient. Age seemed to predict insufficient rehabilitation, where older patients had a demand for more information about support and younger patients demanded help to manage symptoms, dealing with social consequences and return to everyday life.

A strength of our study was the access to combine data from comprehensive and accurate databases, enabling investigation of a whole population-based cancer cohort. Patients were followed individually over time, thereby reducing the risk of selection bias and information bias to a minimum. To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare the epidemiology of long- and short-term survivors in a population-based cohort of unselected, incident cancer patients.

Conclusion

The population of incident cancer patients, characterized by its epidemiology and crude survival, is relevant as “denominator population” for healthcare systems’ estimations of cancer care needs and planning of care programs. We suggest two-years’ crude survival to represent a relevant measure between the proportions of cancer patients, who may become users of either rehabilitation programs or palliative care initiatives. A minor proportion of cancer patients, those who survive from two to five years, could be termed medium-term survivors. This proportion could function as an estimate for patients, who may need rehabilitation in the beginning of their trajectory and then shift to palliative care due to recurrence of their cancer. So, instead of one common pathway with five phases for all cancer patients, our results suggest two generic trajectories for incident cancer patients; one for long-term and medium-term survivors, and one for short-term survivors. In one trajectory, the patients follow the known five phase-model with a small proportion patients, who will recur. In the other trajectory, the patients will continue to have cancer present, from the time of the diagnosis, throughout the trajectory and until the end of life. Occasionally, patients in the “palliative care-trajectory” may respond unexpectedly well to antineoplastic therapy, and shift to the “rehabilitation-trajectory”. For the healthcare systems’ planning of cancer care programs, these deviations will be of less importance because they would be few in numbers. However, for patients and families it is important that rehabilitation and palliative care programs work in close coordination to allow a seamless transition for one approach to the other if needed, with minimal logistic and emotional distress.

Under the hypothesis, that most population-based cohorts of incident cancer patients in the western world display similar proportions of long-, medium- and short-term survivors, we find it important to acknowledge that incident cancer patients enter two generic trajectories – one for patients, who go “beyond a diagnosis of cancer”, and one for patients, who have to live with their cancer present from the time of the diagnosis and until the end of life. If these facts are ignored by organizers of cancer care, we suspect the large proportion of short-term survivors face a risk of being “lost in comprehension” instead of being “lost in transition” when rehabilitation programs and palliative care programs are planned by the healthcare systems.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their appreciation to pharmacist Hanne Knoldsborg, who originally created the database containing data on chemotherapy. The authors also wish to express their appreciation to the Department of Cancer Prevention & Documentation, The Danish Cancer Society for cooperation with the data on the cancer patients in the region investigated (former Funen County).

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Treanor C, Donnelly M. An international review of the patterns and determinants of health service utilisation by adult cancer survivors. BMC Health Serv Res 2012; 12:316.

- Siegel R, DeSantis C, Virgo K, Stein K, Mariotto A, Smith T, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2012;62:220–41.

- Coleman MP, Quaresma M, Berrino F, Lutz JM, De AR, Capocaccia R, et al. Cancer survival in five continents: A worldwide population-based study (CONCORD). Lancet Oncol 2008;9:730–56.

- Vickers AJ. Prediction models in cancer care. CA Cancer J Clin 2011;61:315–26.

- Brenner H, Hakulinen T. Implications of incomplete registration of deaths on long-term survival estimates from population-based cancer registries. Int J Cancer 2009;125: 432–7.

- Hui D, Mori M, Parsons HA, Kim SH, Li Z, Damani S, et al. The lack of standard definitions in the supportive and palliative oncology literature. J Pain Symptom Manage 2012;43: 582–92.

- Bausewein C, Higginson IJ. Challenges in defining ‘palliative care’ for the purposes of clinical trials. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2012;6:471–82.

- Jarlbaek L, Hansen DG, Bruera E, Andersen M. Frequency of opioid use in a population of cancer patients during the trajectory of the disease. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2010;22:199–207.

- Bruera E, Russell N, Sweeney C, Fisch M, Palmer JL. Place of death and its predictors for local patients registered at a comprehensive cancer center. J Clin Oncol 2002;20: 2127–33.

- Bruera E, Hui D. Conceptual models for integrating palliative care at cancer centers. J Palliat Med 2012;15:1261–9.

- Lynn J. Trajectories of illness across time. Sick to death and not going to take it anymore! Berkeley, California: University of California Press; 2004.

- Pollack LA, Greer GE, Rowland JH, Miller A, Doneski D, Coughlin SS, et al. Cancer survivorship: A new challenge in comprehensive cancer control. Cancer Causes Control 2005; 16(Suppl 1):51–9.

- Svendsen RP, Stovring H, Hansen BL, Kragstrup J, Sondergaard J, Jarbol DE. Prevalence of cancer alarm symptoms: A population-based cross-sectional study. Scand J Prim Health Care 2010;28:132–7.

- Kildemoes HW, Christiansen T, Gyrd-Hansen D, Kristiansen IS, Andersen M. The impact of population ageing on future Danish drug expenditure. Health Policy 2006;75:298–311.

- Gjerstorff ML. The Danish Cancer Registry. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7 Suppl):42–5.

- Hallas J. Conducting pharmacoepidemiologic research in Denmark. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2001;10:619–23.

- Jarlbaek L. Cancer patients’ use of opioids: A pharmaco-epidemiological view. Faculty of Health Sciences; University of Southern Denmark; 2005.

- de Boer AG, Verbeek JH, Spelten ER, Uitterhoeve AL, Ansink AC, de Reijke TM, et al. Work ability and return-to-work in cancer patients. Br J Cancer 2008;98: 1342–7.

- Mols F, Thong MS, Vreugdenhil G, van de Poll-Franse LV. Long-term cancer survivors experience work changes after diagnosis: Results of a population-based study. Psychooncology 2009;18:1252–60.

- Olden TE, Schols JM, Hamers JP, Van De Schans SA, Coebergh JW, Janssen-Heijnen ML. Predicting the need for end-of-life care for elderly cancer patients: Findings from a Dutch regional cancer registry database. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2012;21:477–84.

- Lichtenfeld L. Cancer care and survivorship planning: Promises and challenges. J Oncol Pract 2009;5:116–8.

- Maher J, McConnell H. New pathways of care for cancer survivors: Adding the numbers. Br J Cancer 2011;105(Suppl 1):S5–10.

- Janssen-Heijnen ML, Gondos A, Bray F, Hakulinen T, Brewster DH, Brenner H, et al. Clinical relevance of conditional survival of cancer patients in Europe: Age- specific analyses of 13 cancers. J Clin Oncol 2010;28: 2520–8.

- Veloso AG, Sperling C, Holm LV, Nicolaisen A, Rottmann N, Thayssen S, et al. Unmet needs in cancer rehabilitation during the early cancer trajectory – a nationwide patient survey. Acta Oncol 2013;52:372–81.

- Higginson IJ, Costantini M. Dying with cancer, living well with advanced cancer. Eur J Cancer 2008;44:1414–24.

- Engholm G, Ferlay J, Christensen N, Bray F, Gjerstorff ML, Klint A, et al. NORDCAN – a Nordic tool for cancer information, planning, quality control and research. Acta Oncol 2010;49:725–36.

- Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Waldron W. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2008, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD. Available from: http://seercancergov/csr/1975_2008/2011 [cited 2012 Nov 23].

- Geyer S, Schlanstedt-Jahn U. [Are there social inequalities in the utilisation of oncological rehabilitation by breast cancer patients?]. Gesundheitswesen 2012;74:71–8.

- Bell K, Ristovski-Slijepcevic S. Cancer survivorship: Why labels matter. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:409–11.

- Institute of Medicine. Executive summary: From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition. In: Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, editors. Committee on cancer survivorship: Improving care and quality of life, Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2005.

- Ross L, Petersen MA, Johnsen A, Lundstroem L, Groenvold M. Are different groups of cancer patients offered rehabilitation to the same extent? A report from the population-based study “The Cancer Patient’s World”. Support Care Cancer 2012;20:1089–100.